Abstract

Mycobacterium simiae is a non-tuberculosis mycobacterium causing pulmonary infections in both immunocompetent and imunocompromized patients. We announce the draft genome sequence of M. simiae DSM 44165T. The 5,782,968-bp long genome with 65.15% GC content (one chromosome, no plasmid) contains 5,727 open reading frames (33% with unknown function and 11 ORFs sizing more than 5000 -bp), three rRNA operons, 52 tRNA, one 66-bp tmRNA matching with tmRNA tags from Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium microti, Mycobacterium marinum, and Mycobacterium africanum and 389 DNA repetitive sequences. Comparing ORFs and size distribution between M. simiae and five other Mycobacterium species M. simiae clustered with M. abscessus and M. smegmatis. A 40-kb prophage was predicted in addition to two prophage-like elements, 7-kb and 18-kb in size, but no mycobacteriophage was seen after the observation of 106 M. simiae cells. Fifteen putative CRISPRs were found. Three genes were predicted to encode resistance to aminoglycosides, betalactams and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B. A total of 163 CAZYmes were annotated. M. simiae contains ESX-1 to ESX-5 genes encoding for a type-VII secretion system. Availability of the genome sequence may help depict the unique properties of this environmental, opportunistic pathogen.

Keywords: Mycobacterium simiae draft genome, non-tuberculous mycobacteria, SOLiD

Introduction

Mycobacterium simiae is the type species for M. simiae, and is phylogenetically related to Mycobacterium triplex [1], Mycobacterium genavense [2], Mycobacterium heidelbergense [3], Mycobacterium lentiflavum [4], Mycobacterium sherrisii [5], Mycobacterium parmense [6], Mycobacterium shigaense [7], Mycobacterium stomatepiae [8] and Mycobacterium florentinum [9]. M. simiae is slow growing and photochromogenic, appearing rust-colored after exposure to light and is the only non-tuberculous mycobacterium that, is niacin positive, like Mycobacterium tuberculosis [10]. M. simiae was isolated initially from rhesus macaques in 1965 [11]. In immunocompetent patients, M. simiae is responsible for lymphadenitis [12,13], bone infection [14], respiratory tract infection [15] and skin infection [16]. M. simiae also causes infection in immunocompromized HIV-infected patients [17,18], including patients with immune reconstruction [19]. Tap water has proven to be a source of M. simiae infection in both community and hospital-acquired infection [20,21]. To understand the genetics of M. simiae in detail, we sequenced and annotated a draft genome of the type strain of M. simiae (DSM 44165T).

Classification and features

M. simiae strain DSM 44165 T is the only genome sequenced strain within the M. simiae complex (Table 1).

Table 1. Classification and general features of Mycobacterium simiae DSM44165T [22].

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [23] | |

| Phylum Actinobacteria | TAS [24] | ||

| Class Actinobacteria | TAS [25] | ||

| Subclass Actinobacteridae | TAS [25,26] | ||

| Order Actinomycetales | TAS [25-28] | ||

| Suborder Corynebacterineae | TAS [25,26] | ||

| Family Mycobacteriaceae | TAS [25-27,29] | ||

| Genus Mycobacterium | TAS [27,30,31] | ||

| Species Mycobacterium simiae | TAS [11,27] | ||

| Gram stain | Weakly positive | TAS [11] | |

| Motility | Non motile | TAS [11] | |

| Sporulation | nonsporulating | NAS | |

| Temperature range | mesophile | TAS [11] | |

| Optimum temperature | 37°C | TAS [11] | |

| Salinity | normal | TAS [11] | |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | aerobic | TAS [11] |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Soil | TAS [11] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living | NAS |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | none | NAS |

| Biosafety level | 2 | NAS | |

| Isolation | Macacus rhesus | TAS [11] | |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | Country India | TAS [11] |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection time | 1965 | TAS [11] |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | 20.593684 | NAS [11] |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | 78.96288 | NAS [11] |

| MIGS-4.3 | Depth | Not reported | TAS [11] |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | Not reported | TAS [11] |

Evidence codes - TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project [32].

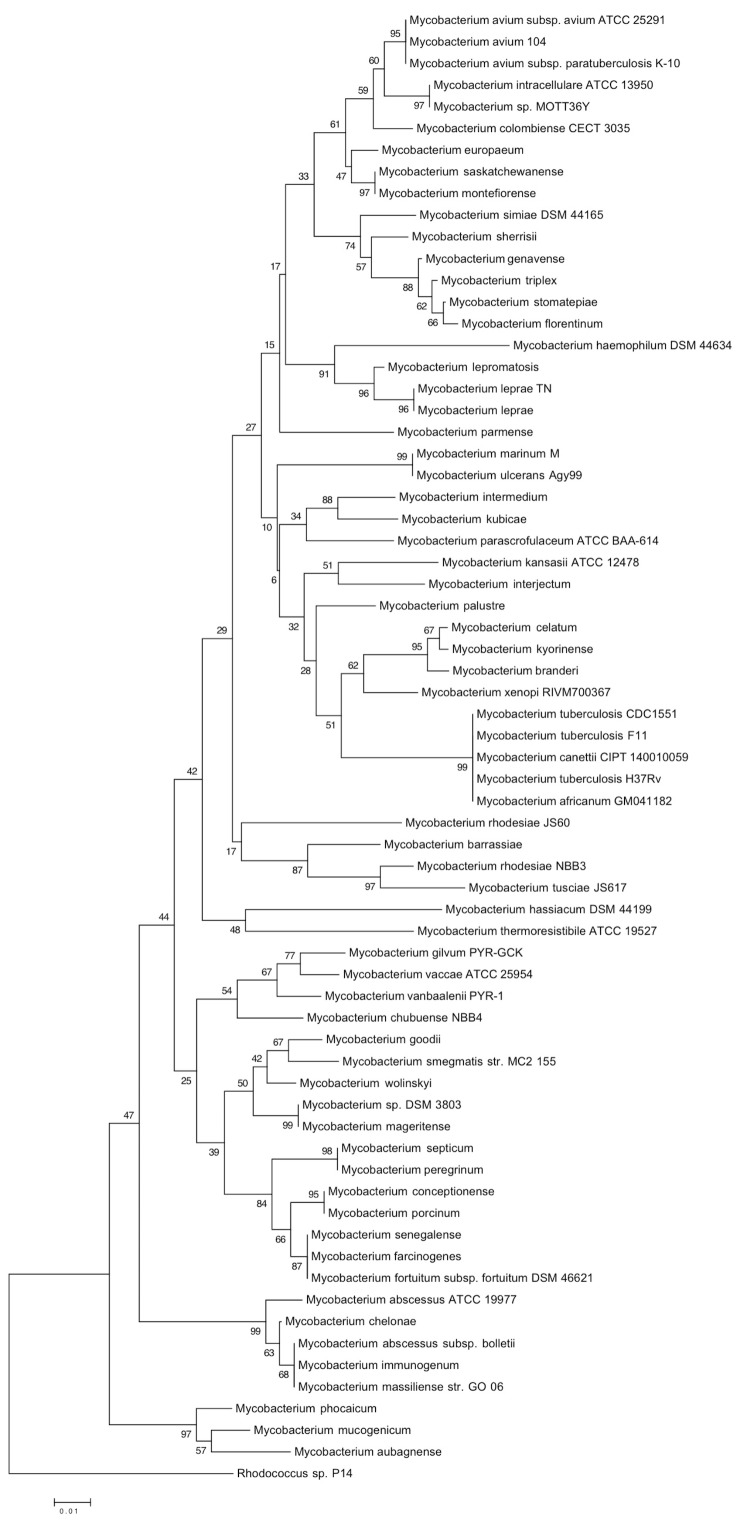

The 16S rRNA gene sequence, derived from the M. simiae strain DSM 44165 T genome sequence showed 100% sequence similarity to that of M. simiae type strain DSM 44165 T /ATCC 25275 T previously deposited in GenBank (GenBank accession: GQ153280.1) and 99% sequence similarity with M. sherrisii (GenBank accession: AY353699.1). The rpoB gene sequence of M. simiae showed 98% similarity with M. sherrisii (GenBank accession: GQ166762.1), the closest mycobacterial species. The rpoB gene sequence-based phylogenetic tree (Figure 1) illustrates that M. simiae DSM 44165 T is phylogentically closest to M. sherrisii, M. genavense, M. triplex, M. stomatepiae and M. florentinum, which are all species constituting the M. simiae complex.

Figure 1.

rpoB gene sequence based phylogenetic tree highlighting the position of Mycobacterium simiae DSM 44165 relative to other type strains within the Mycobacterium genus. Phylogenetic inferences obtained using the neighbor-joining method within MEGA. Numbers at the nodes are percentages of bootstrap values obtained by repeating the analysis 1,000 times to generate a majority consensus tree. Rhodococcus sp P14 was used as an outgroup.

The M. simiae genome shares, 87%, 83%, 79% and 76% nucleotide similarity with the closest sequenced genomes of the species Mycobacterium sp: MOTT36Y (CP003491.1), M. intracellulare ATCC 13950 (ABIN00000000), M. indicus pranii MTCC 9506 (CP002275.1) and M. avium 104 (CP000479.1), respectively.

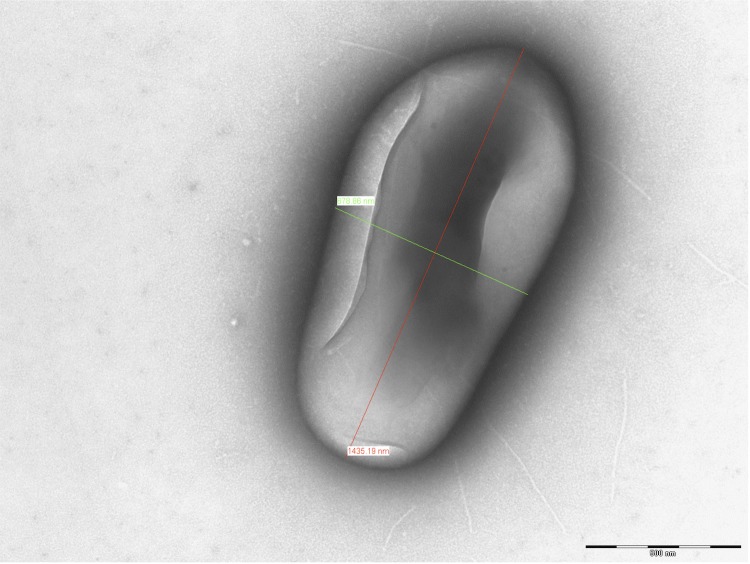

In order to complement the phenotypic traits previously reported for M. simiae [10], we observed 106 M. simiae cells by electron microscopy as previously described [33]. Briefly, M. simiae cells were deposited on carbon-reinforced Formvar-coated grids and negatively stained with 1.5 (w:v) phosphotungstic acid (ph 7.0). The grids were examined using a Hitachi HU-12 electron microscope (FEI, Lyon, France) at 89× magnification. No phage was observed in M. simiae DSM 44165 T cultures. M. simiae cells measured 1,226 nm in length and 594 nm in width of (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Electron microscopy graph of M. simiae DSM 44165T

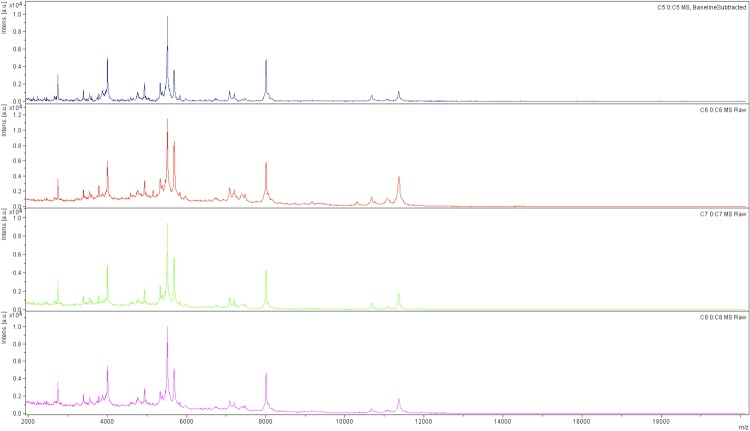

Matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS protein analysis was carried out as previously described [34]. The M. simiae spectra were imported into the MALDI Bio Typer software (version 2.0, Bruker, Wissembourg, France) and analyzed by standard pattern matching (with default parameter settings) against the main spectra of 3,769 bacteria, including spectra from 79 validly named mycobacterial species used as reference data, in the Bio Typer database (updated March 15th, 2012). The method of identification includes the m/z from 3,000 to 15,000 Da. For every spectrum, 100 peaks at most were taken into account and compared with the spectra in the database. For M. simiae DSM 44165 T, the score obtained was 1.7, matching that of M. simiae 423-B-I-2007-BSI thus suggesting that our isolate was a member of a M. simiae species. We incremented our database with the spectrum from M. simiae DSM 44165 T (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reference mass spectrum from M. simiae strain DSM 44165. Spectra from 5 individual colonies were compared and a reference spectrum was generated.

Genome sequencing and annotation

Genome project history

M. simiae is the first member of the M. simiae species complex for which a genome sequence has been completed. This organism was selected to gain understanding in the genetics of M. simiae complex in detail (Table 2).

Table 2. Project information.

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS-31 | Finishing quality | High-quality draft |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | One 454 paired end 3-kb library |

| MIGS-29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 GS FLX Titanium |

| MIGS-31.2 | Fold coverage | 15.33 |

| MIGS-30 | Assemblers | Newbler version 2.5.3 |

| MIGS-32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal |

| EMBL-EBI/NCBI project ID | PRJEB1560 | |

| EMBL-EBI/Genbank ID | CBMJ020000001-CBMJ020000359 | |

| EMBL-EBI Date of Release | June 27, 20113 | |

| MIGS-13 | Source material identifier | DSM 44165T |

| Project relevance | Pangenome of opportunistic mycobacteria |

Growth conditions and DNA isolation

M. simiae strain DSM 44165 T was grown in 7H9 broth (Difco, Bordeaux, France) enriched with 10% OADC (oleic acid, bovine serum albumin, dextrose and catalase) in 8-mL tubes at 37°C. The culture was centrifuged at 8,000 g for 10 min, the pellet was resuspended in 250 µL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and inactivated by heating at 95°C for one h. The sample was then transferred into a sterile screw-cap Eppendorf tube containing 0.3 g of acid-washed glass beads (Sigma, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France) and shaken using a Bio 101 Fast Prep instrument (Qbiogene, Strasbourg, France) at level 6.5 (full speed) for 45 s. The supernatant was incubated overnight at 56°C with 25 µL proteinase K (20 mg/ml) and 180 µL T1 buffer from the Nucleospin Tissue Mini kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France). After a second mechanical lysis and a 15 min incubation at 70°C, total DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin Tissue Mini kit (Macherey-Nagel, Hoerdt, France). The extracted DNA was eluted into 100 µL of elution buffer and stored at –20°C until used.

Genome sequencing and assembly

The concentration of the DNA was measured using a Quant-it Picogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios Tecan fluorometer at 79.36 ng/µl. A 5 µg quantity of DNA was mechanically fragmented on the Covaris device (KBioScience-LGC Genomics, Teddington, UK) through miniTUBE-Red 5Kb. The DNA fragmentation was visualized in an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer on a DNA labchip 7500 with an optimal size of 3.57kb. The library was constructed according to the 454 Titanium paired end protocol (Roche, Boulogne-Billancourt, France). Circularization and nebulization were performed to generate a pattern with an optimum at 415 bp. After PCR amplification through 17 cycles followed by double size selection, the single stranded paired end library was quantified on the Quant-it Ribogreen kit (Invitrogen) on the Genios_Tecan fluorometer at 865pg/µL. The library concentration equivalence was calculated as 1.91E+09 molecules/µL. The library was stocked at -20°C until used. The library was clonally amplified with 0.5 cpb in 2 emPCR reactions with the GS Titanium SV emPCR Kit (Lib-L) v2 (Roche, Boulogne-Billancourt, France). The yield of the emPCR was 20.2%, which is somewhat high compared to the range of 5 to 20% from the Roche procedure. A total of 790,000 beads were loaded on the GS Titanium PicoTiterPlate PTP Kit 70x75 and sequenced with a GS Titanium Sequencing Kit XLR70 (Roche, Boulogne-Billancourt, France). The run was done overnight and analyzed on the cluster through the gsRunBrowser and gsAssembler_Roche. A total of 241,405 passed filter wells were obtained and generated 88.64Mb with an average 367 bp length. The passed filter sequences were assembled on the gsAssembler (Roche, Boulogne-Billancourt, France), with 90% identity and 40 bp as overlap, yielding one scaffold and 338 large contigs (>1,500 bp), generating a genome size of 5.78 Mb, which corresponds to a coverage of 15.33 × genome equivalents.

Genome annotation

Open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal [35,36] with default parameters. The predicted bacterial protein sequences were searched against the NCBI NR database, UNIPROT [37] and against COGs [38] using BLASTP. The ARAGORN software tool [39] was used to find tRNA genes, whereas ribosomal RNAs were found by using RNAmmer [40] and BLASTn against the NR database. Proteins were also checked for domain using a hidden Markov model (HMM) search against the PFAM database [41]. The Tandem Repeat Finder was used for repetitive DNA prediction [42]. The prophage region prediction was completed using PHAST (PHAge Search Tool) [43]. CRISPRs were found using the CRISPER finder [44].

The antibiotic resistance genes were annotated using. The CAZYmes, which are enzymes involved in the synthesis, metabolism, and transport of carbohydrates were annotated using CAZYmes Analysis Toolkit (CAT) (mothra.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/cat.cgi?tab=CAZymes)

Genome properties

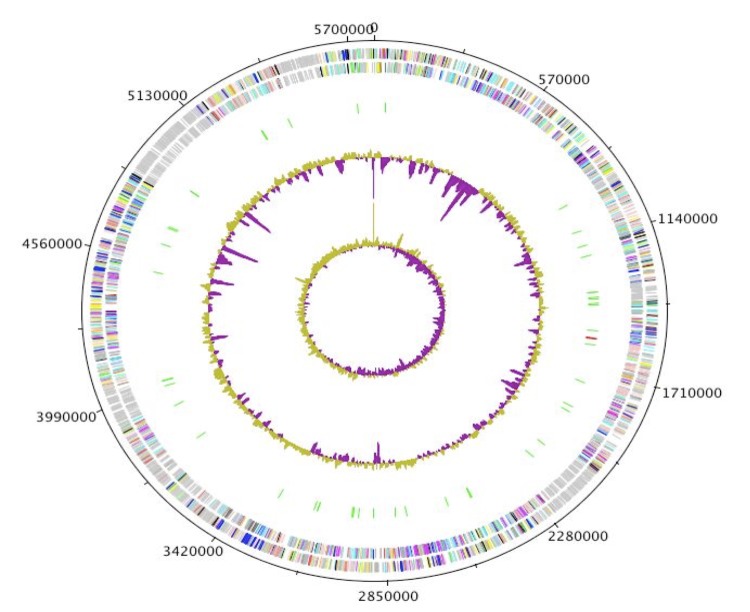

M. simiae strain DSM 44165 T genome consists of a 5,782,968-pb long (65.15% GC content) chromosome without plasmids (Figure 4). Table 3 presents the nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome and the distribution of genes into COGs functional categories is presented in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Graphical circular map of the chromosome. From outside to the center: Genes on the forward strand (colored by COG categories), genes on the reverse strand (colored by COG categories), RNA genes (tRNAs green, rRNAs red), GC content, and GC skew.

Table 3. Nucleotide content and gene count levels of the genome.

| Attribute | Value | % of totala |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 5,782,968 | 100 |

| DNA coding region (bp) | 5,072,379 | 87.71 |

| DNA G+C content (bp) | 3,767,609 | 65.15 |

| Number of replicons | 1 | |

| Extrachromosomal elements | 0 | |

| Total genes | 5,782 | 100 |

| RNA genes | 55 | 0.95 |

| Protein-coding genes | 5,727 | 99.04 |

| Genes with function prediction | 4,673 | 81.6 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4,105 | 71,67 |

| Genes with peptide signals | 377 | 6.58 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1,144 | 19.97 |

| CRISPR repeats | 15 |

a) The total is based on either the size of the genome in base pairs or the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome

Table 4. Number of genes associated with the 25 general COG functional categories.

| Code | Value | % agea | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 157 | 2.74 | Translation |

| A | 1 | 0.02 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 410 | 7,16 | Transcription |

| L | 171 | 2.99 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 2 | 0.03 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 34 | 0.59 | Cell cycle control, mitosis and meiosis |

| Y | 0 | 0 | Nuclear structure |

| V | 41 | 0.72 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 169 | 2.95 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 162 | 2.83 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 48 | 0.84 | Cell motility |

| Z | 0 | 0 | Cytoskeleton |

| W | 0 | 0 | Extracellular structures |

| U | 23 | 0.40 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 132 | 2.30 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 400 | 6.98 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 212 | 3.70 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 151 | 2.64 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 11 | 0.19 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 158 | 2,76 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 418 | 7,30 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 192 | 3,35 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 433 | 7,56 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 656 | 11,45 | General function prediction only |

| S | 291 | 5,08 | Function unknown |

| 1622 | 1,25 | Not in COGs | |

a) The total is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the annotated genome.

The genome contains three rRNA (5S rRNA, 23S rRNA and 16S rRNA), 52 tRNA genes with one transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) and 5,727 ORFs with 4,673 ORFs (81.6%) having at least one PFAM domain. The properties and the statistics of the genome are summarized in Table 3. Of the coding sequences, 66% could be assigned to COG families (Table 4).

The draft M. simiae genome has 389 DNA repetitive sequences and contains a 40-kb prophage like region with attachment sites. Two prophage like elements sized 7 kb and 8 kb containing six and 12 phage-like proteins respectively. A total of 15 questionable CRISPRs (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) were found and three genes encoding resistance to aminoglycosides, betalactamines and Macrolide-Lincosamide-StreptograminB (Table 3) were annotated. M. simiae DSM 44165T showed the presence of 163 Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes genes belonging to 36 CAZy family (supplementary data S1).

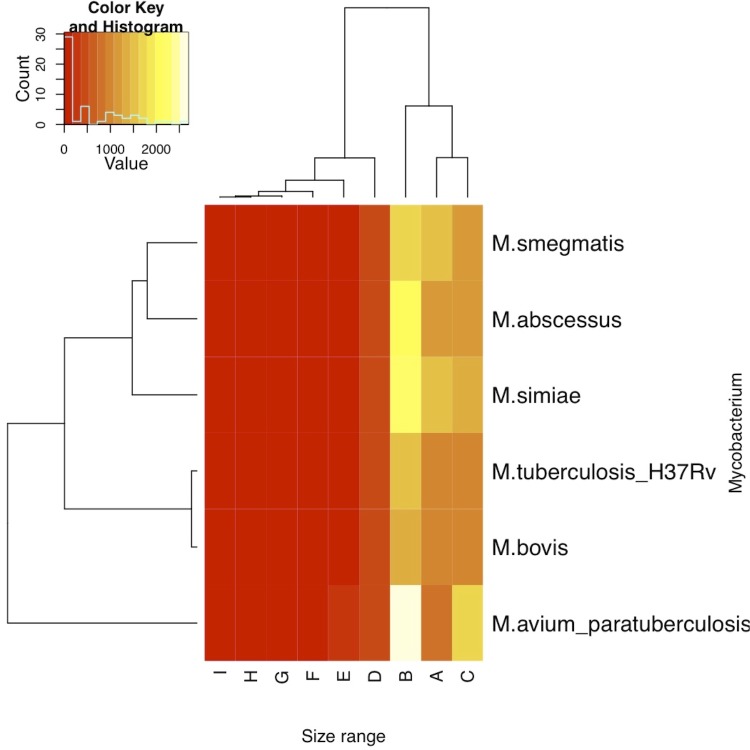

Analysis of the distribution of M. simiae ORF size revealed 11 ORFs > 5,000-pb, including two ORFs > 10,000-pb: a 12,942-bp ORF showed 77% similarity with a M. avium 104 gene encoding a linear gramidicin synthase subunit D; a 14,415-bp ORF showed no similarity with NR database. We verified the open reading frames of the two ORFs using ORFs finder online software [45] and found that these ORFs encode 4,313 and 4,804 amino acids proteins respectively. A heatmap based on the distribution of ORFs sizes in M. simiae and five other genomes was done in R [46], which clusters M. simiae with M. abscessus and M. smegmatis, indicating that the three genomes have similar ORFs size distribution (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Heatmap of the ORFs size distribution of M. simiae compared with 5 other Mycobacterium genomes.

Recent evidence shows that mycobacteria have developed novel and specialized secretion systems for the transport of extracellular proteins across their hydrophobic, highly impermeable, cell wall [47]. M. tuberculosis genomes encode up to five of these transport systems, and ESX-1 and ESX-5 systems are involved in virulence [47]. In comparison with M. tuberculosis H37Rv type VII clusters using Blastp, a total of 77 proteins encoding a type VII secretion system were annotated in M. simiae (supplementary data II). ESX-5 seems to be a conserved cluster between M. tuberculosis and M. simiae, in agreement with opportunistic pathogenicity of M. simiae.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Unité de Recherche sur les Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales Emergentes (URMITE), UMR CNRS 7278, IRD 198, INSERM 1095, Faculté de Médecine, Marseille, France

References

- 1.Floyd MM, Guthertz LS, Silcox VA, Duffey PS, Jang Y, Desmond EP, Crawford JT, Butler WR. Characterization of an SAV organism and proposal of Mycobacterium triplex sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:2963-2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Böttger EC, Hirschel B, Coyle MB. Mycobacterium genavense sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1993; 43:841-843 10.1099/00207713-43-4-841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfyffer GE, Weder W, Strässle A, Russi EW. Mycobacterium heidelbergense species nov. infection mimicking a lung tumor. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27:649-650 10.1086/517142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Springer B, Wu WK, Bodmer T, Haase G, Pfyffer GE, Kroppenstedt RM, Schröder KH, Emler S, Kilburn JO, Kirschner P, et al. Isolation and characterization of a unique group of slowly growing mycobacteria: description of Mycobacterium lentiflavum sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 1996; 34:1100-1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selvarangan R, Wu WK, Nguyen TT, Carlson LD, Wallis CK, Stiglich SK, Chen YC, Jost KC, Jr, Prentice JL, Wallace RJ, Jr, et al. Characterization of a novel group of mycobacteria and proposal of Mycobacterium sherrisii sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42:52-59 10.1128/JCM.42.1.52-59.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanti F, Tortoli E, Hall L, Roberts GD, Kroppenstedt RM, Dodi I, Conti S, Polonelli L, Chezzi C. Mycobacterium parmense sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2004; 54:1123-1127 10.1099/ijs.0.02760-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakanaga K, Hoshino Y, Wakabayashi M, Fujimoto N, Tortoli E, Makino M, Tanaka T, Ishii NJ. Mycobacterium shigaense sp. nov., a novel slowly growing scotochromogenic mycobacterium that produced nodules in an erythroderma patient with severe cellular immunodeficiency and a history of Hodgkin's disease. J Dermatol 2012; 39:389-396 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pourahmad F, Cervellione F, Thompson KD, Taggart JB, Adams A, Richards RH. Mycobacterium stomatepiae sp. nov., a slowly growing, non-chromogenic species isolated from fish. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008; 58:2821-2827 10.1099/ijs.0.2008/001164-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tortoli E, Rindi L, Goh KS, Katila ML, Mariottini A, Mattei R, Mazzarelli G, Suomalainen S, Torkko P, Rastogi N. Mycobacterium florentinum sp. nov., isolated from humans. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2005; 55:1101-1106 10.1099/ijs.0.63485-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rynkiewicz DL, Cage GD, Butler WR, Ampel NM. Clinical and microbiological assessment of Mycobacterium simiae isolates from a single laboratory in southern Arizona. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 26:625-630 10.1086/514573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karassova V, Weissfeiler J, Krasznay E. Occurrence of atypical mycobacteria in Macacus rhesus. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung 1965; 12:275-282 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel NC, Minifee PK, Dishop MK, Munoz FM. Mycobacterium simiae cervical lymphadenitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2007; 26:362-363 10.1097/01.inf.0000258614.98241.4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz AT, Goytia VK, Starke J. Mycobacterium simiae complex infection in an immunocompetent child. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:2745-2746 10.1128/JCM.00359-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartanusz V, Savage JG. Destructive Mycobacterium simiae infection of the lumbar spine and retroperitoneum in an immunocompetent adult. Spine J 2012; 12:534-535 10.1016/j.spinee.2012.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baghaei P, Tabarsi P, Farnia P, Marjani M, Sheikholeslami FM, Chitsaz M, Gorji Bayani P, Shamaei M, Mansouri D, Masjedi MR, et al. Pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium simiae in Iran's national referral center for tuberculosis. J Infect Dev Ctries 2012; 6:23-28 10.3855/jidc.1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piquero J, Casals VP, Higuera EL, Yakrus M, Sikes D, de Waard JH. Iatrogenic Mycobacterium simiae skin infection in an immunocompetent patient. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10:969-970 10.3201/eid1005.030681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Abdely HM, Revankar SG, Graybill JR. Disseminated Mycobacterium simiae infection in patients with AIDS. J Infect 2000; 41:143-147 10.1053/jinf.2000.0700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alcalá L, Ruiz-Serrano MJ, Cosín J, García-Garrote F, Ortega A, Bouza E. Disseminated infection due to Mycobacterium simiae in an AIDS patient: case report and review. Clin Microbiol Infect 1999; 5:294-296 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vitoria MA, González-Domínguez M, Salvo S, Crusells MJ, Letona S, Samper S, Sanjoaquín I. Mycobacterium simiae pulmonary infection unmasked during immune reconstitution in an HIV patient. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 75:101-103 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conger NG, O'Connell RJ, Laurel VL, Olivier KN, Graviss EA, Williams-Bouyer N, Zhang Y, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ., Jr Mycobacterium simiae outbreak associated with a hospital water supply. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004; 25:1050-1055 10.1086/502342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Sahly HM, Septimus E, Soini H, Septimus J, Wallace RJ, Pan X, Williams-Bouyer N, Musser JM, Graviss EA. Mycobacterium simiae pseudo-outbreak resulting from a contaminated hospital water supply in Houston, Texas. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:802-807 10.1086/342331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Sterk P, Tatusova T, Thomson N, Allen MJ, An-giuoli SV, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequence (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol 2008; 26:541-547 10.1038/nbt1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87:4576-4579 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garrity GM, Holt JG. The Road Map to the Manual. In: Garrity GM, Boone DR, Castenholz RW (eds), Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Second Edition, Volume 1, Springer, New York, 2001, p. 119-169. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stackebrandt E, Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL. Proposal for a new hierarchic classification system, Actinobacteria classis nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; 47:479-491 10.1099/00207713-47-2-479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhi XY, Li WJ, Stackebrandt E. An update of the structure and 16S rRNA gene sequence-based de-finition of higher ranks of the class Actinobacteria, with the proposal of two new suborders and four new families and emended descriptions of the existing higher taxa. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009; 59:589-608 10.1099/ijs.0.65780-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skerman VBD, McGowan V, Sneath PHA. Approved Lists of Bacterial Names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980; 30:225-420 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchanan RE. Studies in the nomenclature and classification of bacteria. II. The primary subdivisions of the Schizomycetes. J Bacteriol 1917; 2:155-164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chester FD. Report of mycologist: bacteriological work. Delaware Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 1897; 9:38-145 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehmann KB, Neumann R. Atlas und Grundriss der Bakteriologie und Lehrbuch der speziellen bakteriologischen Diagnostik, First Edition, J.F. Lehmann, München, 1896, p. 1-448. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Runyon EH, Wayne LG, Kubica GP. Genus I. Mycobacterium Lehmann and Neumann 1896, 363. In: Buchanan RE, Gibbons NE (eds), Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology, Eighth Edition, The Williams and Wilkins Co., Baltimore, 1974, p. 682-701. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000; 25:25-29 10.1038/75556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brenner S, Horne RW. A negative staining method for high resolution electron microscopy of viruses. Biochim Biophys Acta 1959; 34:103-110 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90237-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:543-551 10.1086/600885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010; 11:119 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prodigal. http://prodigal.ornl.gov/

- 37.UNIPROT http://www.uniprot.org/

- 38.Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 2003; 4:41 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 2004; 32:11-16 10.1093/nar/gkh152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:3100-3108 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:D290-D301 10.1093/nar/gkr1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 1999; 27:573-580 10.1093/nar/27.2.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: A Fast Phage Search Tool. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39:W347-W352 10.1093/nar/gkr485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.CRISPER http://crispr.u-psud.fr/server/

- 45.ORFs http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gorf/

- 46.Heiberger RM, Holland B. 2004. Statistical Analysis and Data Display: An Intermediate Course with Examples in S-Plus, R, and SAS Springer Texts in Statistics. Springer. ISBN 0-387-40270-5. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdallah AM, Gey van Pittius NC, Champion PA, Cox J, Luirink J, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Appelmelk BJ, Bitter W. Type VII secretion--mycobacteria show the way. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007; 5:883-891 10.1038/nrmicro1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]