Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study is to investigate the characteristics of patients experience cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA) in the acute phase following aortic dissection and aneurysm (AD).

Materials and Methods:

Patients who were transported to this department from January 2005 to December 2010 and subsequently diagnosed with AD were included in this study. Patients with asymptomatic AD or those with AD that did not develop CPA were excluded. The AD was classified into four categories: Stanford A (SA), Stanford B (SB), thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The frequency of witnessed collapse, gender, average age, past history including hypertension, vascular complications and diabetes mellitus, the initial complaint at the timed of dissection, initial electrocardiogram at scene, classification of CPA and survival ratio were compared among the patient groups.

Results:

There were 24 cases of SA, 1 case of the SB, 8 cases of ruptured TAA and 9 cases of ruptured AAA. The frequency of males among all subjects was 69%, the average age was 72.3 years old and the frequency of hypertension was 47.6%. There was no ventricular fibrillation (VF) when the patients with AD collapsed. A loss of consciousness was the most common complaint. The outcome of the subjects was poor; however, three patients with SA achieved social rehabilitation. Two out of the three had cardiac tamponade and underwent open heart massage.

Conclusion:

The current study revealed that mortality of cardiac arrest caused by the AD remains very high, even when return of spontaneous circulation was obtained. VF was rare when the patients with AD collapsed. While some cases with CPA of SA may achieve a favorable outcome following immediate appropriate treatment.

Keywords: Aneurysm, aortic dissection, cardiopulmonary arrest

INTRODUCTION

A patient with aortic dissection and aneurysm (AD) presents with a variety of complaints and symptoms. The major complaints include severe chest and back pain, which can move with the progression of AD. However, AD can be painless. In addition, AD can lead to heart failure, syncope, stroke, paraplegia, anuria or sudden death.[1] This facility treated patients with severe AD that experienced cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA). A few studies has analyzed the association of AD with CPA.[2,3] This study reviewed the experience of this institute with AD and aneurysm patients that develop CPA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board and informed consent was waived. The Department of Traumatology and Critical Care Medicine, National Defense Medical College is located in Tokorozawa city, Saitama prefecture, near Tokyo. This department controlled the First Western District of Saitama Prefecture, which is inhabited by approximately 1.08 million people. Patients with CPA, shock, unconsciousness, life-threatening disease such as AD, acute myocardial infarction, severe cases of trauma and overdose are transported to this department.

Patients who were transported to this department between January 2005 and December 2010 and received a diagnosis of AD were included in this study. Those with asymptomatic AD or those with AD that did not experience CPA were excluded. The definition of CPA was cardiac arrest, which was recognized either by emergency medical technicians before admission to hospital or by physicians in the hospital setting after manually checking the pulsation of the bilateral carotid artery and/or femoral artery. The CPA was classified into three categories: Cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival: CPA-OA, Cardiopulmonary arrest on arrival, out-of-hospital return of spontaneous circulation: Oh-ROSC and Cardiopulmonary arrest within 1 h after arrival CPA-AA. The AD was classified into four categories: Stanford A (SA), Stanford B (SB), thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) and abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). This study evaluated the frequency of witnessed collapse, gender, average age, past history including hypertension, vascular complications (stroke, coronary disease or complicated aortic disease) and diabetes mellitus (DM), initial complaint when dissection occurred, initial electrocardiogram (ECG) at the scene, the ECG at collapse who was not cardiac arrest at the scene, classification of CPA, estimated cause of the CPA and survival ratio. The estimated cause of CPA was classified into five categories including: Bleeding: Massive fluid collection as diagnosed by roentgen, sonography or computed tomography (CT), tamponade: As diagnosed by sonography or CT, myocardial infarction; as diagnosed by elevation of troponin T, suffocation and unknown.

RESULTS

A total of 4222 patients were transported to this department during the study period. 55 patients were diagnosed with AD. The AD was diagnosed by chest CT, chest X-ray and/or sonography. Five patients had asymptomatic AD and eight patients that did not develop CPA were excluded. The remaining 44 patients with AD were evaluated.

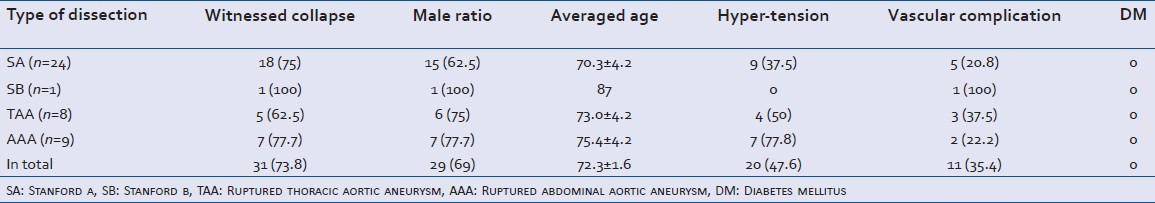

The subject's backgrounds are shown in Table 1. There were 24 cases of SA, 1 case of SB, 8 cases of ruptured TAA and 9 cases of ruptured AAA. The total frequency of males was 69%, the average age was 72.3 (range: 50-91) years old, the frequency of hypertension was 47.6%, the frequency of vascular complications was 35.4% (SA: 3 cases of stroke and 2 cases of coronary disease, the SB: 1 case of coronary disease; TAA: 2 cases of AAA and 1 case of coronary disease, the AAA: 2 cases of stroke). None of the subjects had DM. 2 cases of AAA were complicated with chronic renal failure.

Table 1.

Background of subjects (n=42)

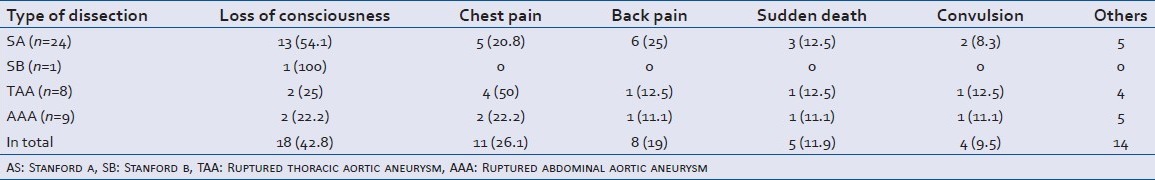

The major complaints at the time of dissection are shown in Table 2. The other complaints are detailed in Table 3. Subjects had multiple complaints and every complaint is herein presented. Loss of consciousness was the most frequent complaint. Three out of 18 that lost consciousness regained consciousness; however, all three became comatose again. Less than half of the subjects experienced chest and back.

Table 2.

Initial complaint in total (n=42)

Table 3.

Details of other complaints or symptoms listed in Table 2

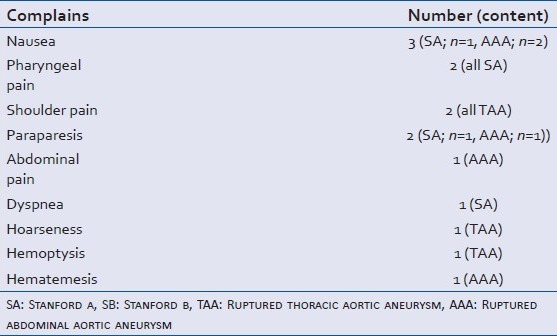

The initial ECG at the scene and the classification of the CPA are shown in Table 4. Spontaneous circulation was recognized at the scene in 18 of 44 patients (42.8%); however, all of these lost spontaneous circulation later. Of the 18 who lost spontaneous circulation, 7 cases were pulseless electrical activity (PEA) while the rest of them were asystole and therefore no cases underwent electric defibrillation. 10 of these cases were CPA-AA.

Table 4.

Type of ECG at scene and CPA (n=42)

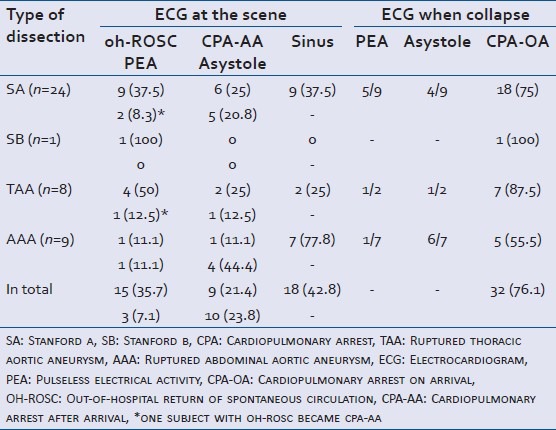

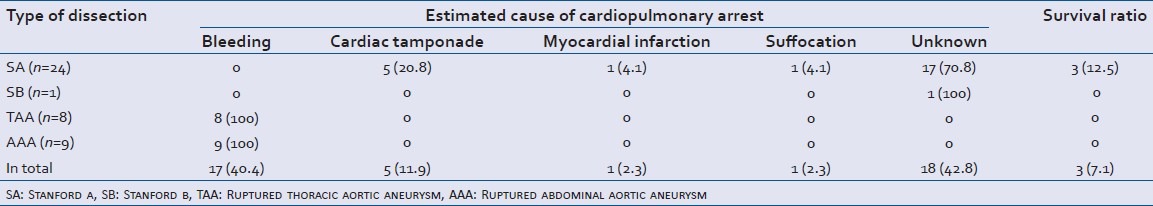

The estimated cause of the CPA and the survival ratio is shown in Table 5. Survival among the subjects was significantly (P = 0.002) less than that among the eight patients excluded because they did not experience CPA (5 cases out of the eight survived). Five of the 8 cases had SA including 3 cases of shock, 2 cases of SB including 1 case of shock and 1 case of AAA with shock. All of the TAA and AAA cases bled to death. In 1 case presenting with suffocation of SA, the cause was found to be due to a rupture of the pseudolumen of the lung as a result of adherence between the aorta and lung due to previous inflammation. All survivors had SA and achieved social rehabilitation. Two of the three experienced CPA in the resuscitation room due to cardiac tamponade and both of them underwent urgent thoracotomy in the resuscitation room to relieve the tamponade and regained spontaneous circulation there.[4,5] One patient subsequently underwent surgical treatment and the rest underwent conservative therapy due to pneumonia. One of the three patients initially showed PEA at the scene. The patient regained spontaneous circulation after external chest compression and tracheal intubation, at the scene. Aggressive control of blood pressure after arriving at the hospital and surgical treatment resulted in a favorable outcome. None of the subjects received percutaneous cardiopulmonary support. None of the fatal cases underwent an autopsy.

Table 5.

Estimated cause of cardiopulmonary arrest and survival ratio (n=42)

DISCUSSION

Chief complaint associated with AD

A loss of consciousness was most frequent complaint in the current series. This was different from previous studies that reported that found chest pain or back pain to be the most common complaint.[1] This difference was probably because the current series focused on AD with CPA and thus included the most severe cases of AD and most could not voice their complaints.

There were 4 cases of convulsion in this study. This is usually due to cerebral hypoperfusion induced by AD.[6] Few reports indicate that life-threatening AD could present convulsion;[7,8,9] thus, physicians who treat patients with convulsions should be aware of this possibility because misdiagnosis of such cases could lead to disastrous results.

There were few cases with hemoptysis or hematemesis in the current study. Hemoptysis may result from a fistula between the aorta and lung due to previous adhesion.[10] Hematemesis may result from a fistula between the aorta and bowel due to previous adhesion or bleeding from ulceration due to ischemia.[11,12]

There was a case with pharyngeal pain or shoulder pain in this study. AD can complicate acute myocardial infarction. Acute myocardial infarction can present pharyngeal pain, shoulder pain or epigastralgia as radiating pain that results from ischemic cardiomyopathy.[13] Accordingly, these complaints may be induced by the acute myocardial ischemia induced by AD. However, one report failed to indicate the existence of cardiac ischemia in a patient with SA that complained of isolate pharyngeal pain.[14] The report suggested that the pharyngeal pain induced by SA might be due to the compression of a nerve by the pathological aortic enlargement.

There was another case with dyspnea in this study. CT indicated the SA with pulmonary edema, suggesting induction of acute heart failure. Accordingly, dyspnea probably was induced by the acute cardiac failure.[15] However, there is a report that SB induced heart failure in a patient with undetected acute heart failure.[16]

No patient presented with stroke even among patients who fulfilled the exclusion criteria. This may be because there are strict rules for stroke management in this area.[17] This rule prevents patient presenting with signs of stroke such as hemiplegia or dysarthria, to be transported to this department.

Some AD patients presented syncope, consciousness disturbance, convulsion, nausea, pharyngeal pain, shoulder pain, dyspnea, hoarseness, hematemesis or hemoptysis. These patients may require truncal enhanced CT to definitively diagnose AD.

ECG findings

The current study revealed no ventricular fibrillation (VF) when the patients with AD collapsed. The most common cause of VF is acute coronary ischemia.[18] However, in an animal study, most attempts to obtain reproducible coronary ligation-induced ventricular fibrillation (VF) in mouse models have failed, but, ischemia/reperfusion-induced VF has been shown to be easy to elicit in most species.[19] Acute myocardial infarction due to AD has been reported to be caused by either retrograde dissection of the coronary ostia or compression of the coronary artery by a false channel.[20] It is considered to be difficult to obtain spontaneous re-canalization and therefore VF might be rare in patients with AD. However, the causes of death from AD have been determined to be heart failure due to myocardial infarction, aortic regurgitation or cardiac tamponade, cerebral infarction, multiple organ failure due to ischemia or circulatory insufficiency, or bleeding due to rupture of the aorta.[21] A low cardiac output including cardiac tamponade, hypoxia due to congestive heart failure or circulatory insufficiency due to massive hemorrhage are all considered to be representative diseases of PEA.[22] Although some cases of asystole in the current study may have demonstrated VF before asystole, both Pierce and Courtney and Meron et al., reported that patients with AD tended to demonstrate PEA after they collapsed.[2,3]

Outcome

The current study found that the outcome of patients with AD was poor. Previous studies report that existence of shock and cardiac tamponade is a pre-operative risk factor of poor prognosis.[23,24,25] None of the 17 patients with AD and CPA in the report by Pierce and Courtney and only 2 of the 46 described by Meron et al., survived.[2,3] CPA is most severe cause of shock so the poor results in the current series are consistent with previous reports, while 18 cases out of all 42 subjects (42.8%) had regained a spontaneous circulation when an emergency medical technician checked the patient. These patients developed CPA during the transition from pre-hospital care to initial hospital care. These results suggest rapid deterioration that could lead to death due to the progression of AD or aneurismal rupture. Aggressive blood pressure control and the administration of sedatives and pain killer were necessary to prevent this progression. However, Japanese law does not allow emergency medical technicians to use such medications in a pre-hospital setting. Therefore, unconscious patients with, chest pain, backache, convulsion or shock may have AD and such patients should be gently, rapidly and directly transported to a medical facility that can treat the patient for AD. While, some cases with SA and cardiac tamponade were successfully resuscitated and achieved a favorable outcome with an open heart massage. Accordingly, a physician that can treat a patient with AD must be able to provide immediate open heart massage if necessary.

CONCLUSION

The current study revealed that mortality of cardiac arrest caused by the AD remains very high, even when ROSC was obtained. VF was rare when the patients with AD collapsed. While some cases with CPA of SA may achieve a favorable outcome following immediate appropriate treatment.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asouhidou I, Asteri T. Acute aortic dissection: Be aware of misdiagnosis. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:25. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierce LC, Courtney DM. Clinical characteristics of aortic aneurysm and dissection as a cause of sudden death in outpatients. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:1042–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meron G, Kürkciyan I, Sterz F, Tobler K, Losert H, Sedivy R, et al. Non-traumatic aortic dissection or rupture as cause of cardiac arrest: Presentation and outcome. Resuscitation. 2004;60:143–50. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanagawa Y, Morita K, Sakamoto T, Okada Y, Isoda S, Maehara T. A satisfactory recovery after emergency direct cardiac massage in type A acute aortic dissection with cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:356–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keiko T, Yanagawa Y, Isoda S. A successful treatment of cardiac tamponade due to an aortic dissection using open-chest massage. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:634.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passman R, Horvath G, Thomas J, Kruse J, Shah A, Goldberger J, et al. Clinical spectrum and prevalence of neurologic events provoked by tilt table testing. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1945–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim TE, Smith DD. Thoracic aortic dissection in an 18-year-old woman with no risk factors. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:e41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mo HH, Chen SC, Lee CC. Seizure: An unusual primary presentation of type A aortic dissection. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:245.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaul C, Dietrich W, Friedrich I, Sirch J, Erbguth FJ. Neurological symptoms in type A aortic dissections. Stroke. 2007;38:292–7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254594.33408.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pauls S, Orend KH, Sunder-Plassmann L, Kick J, Schelzig H. Endovascular repair of symptomatic penetrating atherosclerotic ulcer of the thoracic aorta. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akiyama K, Hirota J, Takiguchi M, Ohsawa S, Nagumo T, Sasaki S. Primary aortoenteric fistula with a chronic isolated abdominal aortic dissection: Report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:441–5. doi: 10.1007/s005950050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Firstenberg MS, Sai-Sudhakar CB, Sirak JH, Crestanello JA, Sun B. Intestinal ischemia complicating ascending aortic dissection: First things first. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:e8–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanagawa Y, Nishimura M, Ohkawara J, Hasegawa K, Yamane M. Acute myocardial infarction presenting with pharyngeal pain alone. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:e287–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu WP, Ng KC. Acute thoracic aortic dissection presenting as sore throat: Report of a case. Yale J Biol Med. 2004;77:53–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto H, Watanabe Y, Sugimori H. Heart failure due to severe supravalvular aortic stenosis in painless type A aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1441–3. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JF, Ge QM, Chen M, Tang LJ, Dong LJ, Pan SM. Painless type B aortic dissection presenting as acute congestive heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:646.e5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanagawa Y, Koyama K, Ohkawara J, Sakamoto T. Target: TPA. Educational efforts help prehospital providers get stroke patients to the appropriate destinations and treatment. EMS Mag. 2010;39:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koplan BA, Stevenson WG. Ventricular tachycardia and sudden cardiac death. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:289–97. doi: 10.4065/84.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stables CL, Curtis MJ. Development and characterization of a mouse in vitro model of ischaemia-induced ventricular fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:397–404. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardozo C, Riadh R, Mazen M. Acute myocardial infarction due to left main compression aortic dissection treated by direct stenting. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheetz L. Aortic dissection. Am J Nurs. 2006;106:55–9. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200604000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, Kronick SL, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 8: Adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S729–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chavanon O, Costache V, Bach V, Kétata A, Durand M, Hacini R, et al. Preoperative predictive factors for mortality in acute type A aortic dissection: An institutional report on 217 consecutives cases. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:43–6. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2006.131433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goossens D, Schepens M, Hamerlijnck R, Hartman M, Suttorp MJ, Koomen E, et al. Predictors of hospital mortality in type A aortic dissections: A retrospective analysis of 148 consecutive surgical patients. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;6:76–80. doi: 10.1016/s0967-2109(97)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zizza A, Pano M, Zaccaria S, Villani M, Guido M Aortic Dissection Study Group. Outcome of acute type A aortic dissection: Single-center experience from 1998 to 2007. J Prev Med Hyg. 2009;50:152–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]