Abstract

We are developing methods for imaging multiple PET tracers in a single scan with staggered injections, where imaging measures for each tracer are separated and recovered using differences in tracer kinetics and radioactive decay. In this work, signal-separation performance for rapid dual-tracer 62Cu-PTSM (blood flow) + 62Cu-ATSM (hypoxia) tumor imaging was evaluated in a large animal model. Four dogs with pre-existing tumors received a series of dynamic PET scans with 62Cu-PTSM and 62Cu-ATSM, permitting evaluation of a rapid dual-tracer protocol designed by previous simulation work. Several imaging measures were computed from the dual-tracer data and compared with those from separate, single-tracer imaging. Static imaging measures (e.g. SUV) for each tracer were accurately recovered from dual-tracer data. The wash-in (k1) and wash-out (k2) rate parameters for both tracers were likewise well recovered (r = 0.87 – 0.99), but k3 was not accurately recovered for PTSM (r = 0.19) and moderately well recovered for ATSM (r = 0.70). Some degree of bias was noted, however, which may potentially be overcome through further refinement of the signal-separation algorithms. This work demonstrates that complementary information regarding tumor blood flow and hypoxia can be acquired by a single dual-tracer PET scan, and also that the signal-separation procedure works effectively for real physiologic data with realistic levels of kinetic model-mismatch. Rapid multi-tracer PET has the potential to improve tumor assessment for image-guide therapy and monitoring, and further investigation with these and other tracers is warranted.

I. INTRODUCTION

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a physiological imaging modality that can characterize, and to some extent quantify, tumor status in vivo. While a number of PET tracers have been developed for imaging different aspects of tumor function, currently available technology precludes imaging of more than one tracer in a single scan. This is because each tracer gives rise to indistinguishable 511 keV photon pairs, and there is no explicit information available to match detected events with the originating tracer when more than one tracer is present. Different PET tracers do, however, experience different biodistribution kinetics. When multiple PET tracers are imaged dynamically with staggered injections, certain information about each tracer can be recovered based on differences in tracer kinetic behavior and radioactive decay as shown in Fig. 1. The initial proof of principle of such an approach has been shown in phantoms (Huang et al., 1982), simulated brain imaging (Ikoma et al., 2001, Koeppe et al., 1998, Koeppe et al., 2001), and for rest-stress cardiac imaging (Rust et al., 2006). Rapid multi-tracer scanning offers a number of advantages over separate single-tracer scans, where delays of around 7 half-lives between scans would be required to reduce residual activity from previous tracer administrations to a low level. These advantages include increased patient throughput, excellent co-registration of the images for each tracer, reduced scan times, greatly improved patient convenience, and reduced radiation exposure since only one transmission or CT scan is needed for attenuation correction.

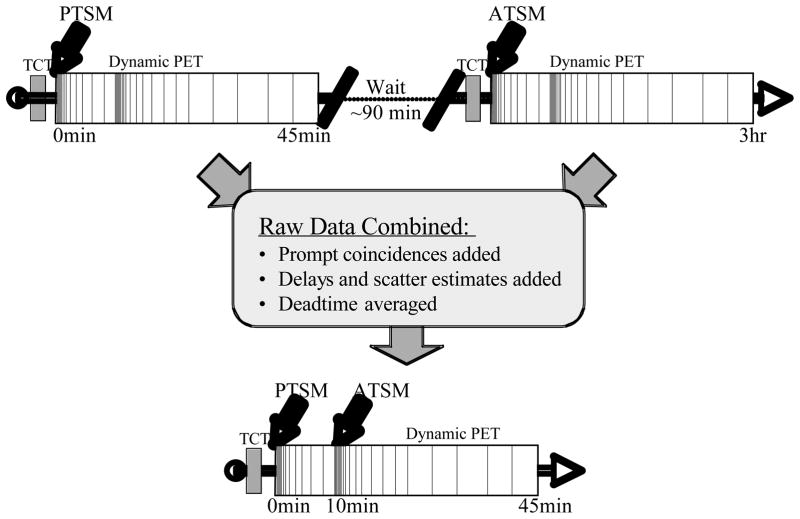

Figure 1.

In rapid dual-tracer PET, a single dynamic scan is obtained with staggered injections of each tracer. Differences in the kinetic behavior of each tracer, along with the offset injections, permit separation of the dual-tracer time-activity curves into single-tracer components, which can then be analyzed using the usual single-tracer methods to obtain static or dynamic imaging measures as desired.

Our group has been systematically investigating rapid multi-tracer PET with the goal of characterizing the feasibility of the approach for several classes of PET tracers, determining which imaging measures can be reliably recovered for which tracers, and which cannot. The information content of simulated multi-tracer time-activity curves was studied as a function of injection timing in (Kadrmas and Rust, 2005), demonstrating the potential to accurately recover individual-tracer signals for several tracer combinations with injections staggered by 10–20 minutes. A more detailed study of one dual-tracer method—simulated 62Cu PTSM + ATSM tumor imaging (see below)—was then performed (Rust and Kadrmas, 2006), characterizing the accuracy and noise properties of rapid imaging of this tracer pair and delineating the tradeoff between tracer recovery performance and overall imaging time. One result of that study was that a dual-tracer protocol with administration of PTSM first, followed by ATSM after a 10 minute delay, provided good performance while maintaining a short overall scan time.

This body of previous work has demonstrated good potential for rapid multi-tracer PET for several tracer combinations, while noting limitations in how rapidly multiple tracers can be imaged as well as fundamental limitations on recovery of slowly varying (e.g. washout) kinetics on non-static backgrounds. However, almost all of this previous work performed with simulated time-activity curves or phantoms. Aside from (Rust et al., 2006), little evaluation of rapid multi-tracer PET with real physiologic data has been performed. While the simulation results are promising, it is necessary to evaluate the performance of multi-tracer PET signal separation in the presence of realistic levels of model-mismatch between the data and the kinetic models used for signal-separation. In practice, kinetic models provide approximations of the underlying physiologic tracer kinetics, and imperfections in scanner calibrations and image reconstruction likewise introduce inconsistencies between the measured data and kinetic models. Such model-mismatch could potentially have significant impact on the performance of multi-tracer PET signal-separation. In this paper, rapid dual-tracer imaging is evaluated for the first time in a large-animal tumor model under carefully-controlled conditions, providing physiologic dual-tracer datasets with realistic kinetics and imaging effects, as well as an ideal gold standard for the evaluation of signal-separation algorithm performance. The ability to recover imaging measures from rapid dual-tracer PET which are similar to those from separately acquired single-tracer scans is evaluated.

Dual-tracer imaging with 62Cu-PTSM (blood flow) and 62Cu-ATSM (hypoxia) was selected as the archetypal multi-tracer paradigm in this paper for several reasons. From a practical standpoint, 62Cu is produced using a portable 62Zn/62Cu generator (Haynes et al., 2000), providing on-demand availability that simplifies the logistics of tracer synthesis and delivery for dual-tracer studies. The 9.7m half-life of 62Cu permits repeat scanning with each tracer after radioactive decay in a single experiment. In addition, blood flow and hypoxia are complex inter-related factors, and imaging both together can provide complementary information to help guide treatment selection, planning, and early response monitoring (Bruehlmeier et al., 2004, Lehtio et al., 2004, Lehtio et al., 2001, Rajendran and Krohn, 2005). PTSM (Flower et al., 2001, Mathias et al., 1994, Mathias et al., 1991) and ATSM (Dehdashti et al., 2003, Fujibayashi et al., 1997, Lewis et al., 1999, Lewis et al., 2001, Takahashi et al., 2000) are chemical analogues. While PTSM distributes in proportion to blood flow and is rapidly reduced and trapped in tissues, ATSM has a lower redox potential and is selectively retained in hypoxic tissues. Unlike many hypoxia tracers, ATSM clears quickly from normoxic tissues and may delineate hypoxic regions within 15–20 minutes after injection. However, the images in such timeframes also contain significant flow-dependence, an issue which may potentially be resolved by concurrent imaging of blood flow and hypoxia using dual-tracer techniques.

In this work, the ability to recover several static and dynamic measures of 62Cu-PTSM and 62Cu-ATSM uptake and retention from rapid dual-tracer imaging data was tested in canines with pre-existing tumors. Signal-separation algorithms were applied to recover individual-tracer components from rapid dual-tracer time-activity curves, and separately acquired single-tracer data were used as the standard for comparison. Canines with pre-existing tumors provide an ethical experimental model with varied physiology, realistic tracer kinetics, a large body size with imaging physics much closer to humans than small animal models, and they allow multiple scans to be performed in a single long-duration experimental session. The following sections describe the experimental setup, data processing and analysis methods, and the results of linear regression analysis comparing static and dynamic imaging measures recovered from rapid dual-tracer PTSM + ATSM imaging versus separate, single-tracer imaging.

II. METHODS

The primary objective of this work was to evaluate to what degree rapid dual-tracer imaging of PTSM + ATSM can recover the same imaging measures as separately-acquired single-tracer scans of each tracer. Note that we are not evaluating how well each tracer measures blood flow or hypoxia; rather, we are determining whether or not rapid dual-tracer imaging of these tracers can provide the same information as conventional single-tracer scans. One experimental approach would be to image each tracer separately (with >7 half-lives between scans for radioactive decay), followed by a dual-tracer scan, then compare the dual-tracer results to the single-tracer results. However, such an approach would produce datasets with several differences between the single-tracer standards and the tracer components within the dual-tracer data, including: differences in injected activity and bolus timing, differences in physiologic state since the first and last scan would be separated in time by several hours (especially since the terminally-ill subject animal was held under anesthesia for an extended period of many hours), different noise realizations, and possible misregistration errors due to any movement including respiratory “creep” over several hours. Repeat PET scans with the same tracer can show differences of up to 15% or larger (Nagamachi et al., 1996), and since these differences are large compared to the accuracy with which some imaging measures may be recovered from rapid dual-tracer scanning, comparison of repeat scans is not sufficiently reproducible for an accurate evaluation in this study.

A second option, which we have used in this study, is to acquire single-tracer scans with each tracer using the dual-tracer scanning sequence, and then combine the raw data to emulate the corresponding dual-tracer dataset. This provides exactly paired single-and dual-tracer source components and eliminates inconsistencies due to the reproducibility of repeat PET scans. While the physiologic state and exact positioning may differ between the single-tracer scans for each tracer, the key point is that the individual-tracer components in the emulated dual-tracer dataset exactly match the single-tracer standards, permitting a direct comparison of imaging measures obtained from the emulated dual-tracer data with those from the single-tracer scans. Section II.C. below describes how the raw data were combined to emulate a dual-tracer scan, and how these data differ from an actual dual-tracer scan.

II.A. Experimental Setup

Four canines (39.3 ± 13.9 kg) with pre-existing tumors were recruited from regional veterinarians and animal shelters under a protocol approved by the University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Each dog had multiple large, well developed tumors (e.g. Fig. 2) and was already scheduled for euthanasia prior to recruitment into the study. Anesthetic induction was achieved by intramuscular injection of approximately 50mg/kg Telazol, followed by tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation with isoflurane in oxygen, keeping the end tidal CO2 at 35mm +/−5mm Hg. Intravenous lines were started in the cephalic veins using Lactated Ringer’s solution at an infusion rate of 15ml/kg/hr. Muscle relaxation was maintained by intravenous administration of 3mg pancuronium bromide as needed. When recumbent, the dogs were weighed and tumor vicinities shaved. An arterial-venous (AV) shunt was placed in the femoral artery for arterial blood sampling during dynamic scanning, and 1000 units of heparin were given intravenously before each scan in order to keep the shunt patent. Following preparation, the dog was placed on the table of the Advance™ scanner (General Electric Medical) and positioned with palpable tumors centered in the field-of-view as much as possible. Tape and Velcro straps were used to secure the dog’s position throughout the study. Radiotracers were administered intravenously and dynamic PET scanning was conducted in 2D mode with septa in place as described below. After completion of all imaging and while still under anesthesia, the animal was euthanized and tissue samples were obtained for histopathologic analysis.

Figure 2.

Terminally-ill canines with pre-existing well-developed tumors provided the experimental model for this study. Here, a 36.4 kg female retriever with 7 cm malignant hemangiopericytoma (arrow) is shown positioned on the imaging table. This animal model provided a relative large body habitus, varied physiology with realistic tracer kinetics, permitting multiple scans to be acquired over a long experimental session for evaluating multi-tracer imaging performance.

II.B. PET Scanning

Each dog received single-tracer dynamic scans with 62Cu-PTSM, 62Cu-ATSM, and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), with delays of 70 minutes or greater between each scan to allow the 62Cu from the previous scan to decay to less than 1% of the administered value. In addition, one animal (dog #4) received an actual dual-tracer PTSM+ATSM scan prior to the FDG scan; this scan demonstrated actual implementation of the dual-tracer imaging technique, but the long delay (> 4hrs) between the first PTSM injection and this scan resulted in sufficient differences (even in the PTSM-only portion of the scan) to rule out valid comparison with the other scans acquired. The FDG scans were used in this paper to assist with tumor localization, though the FDG data and multi-tracer emulation methods will also be used in future work to study dual- and triple-tracer PET with FDG, PTSM, and ATSM. That work, however, requires additional development of signal-separation algorithms and falls outside the scope of this paper.

Figure 3 provides an overview of the experimental approach and dual-tracer emulation procedure. A 10 minute transmission scan was performed prior to injection of each tracer for attenuation correction and to detect any misalignment between scans (none noted). The emulated dual-tracer scan had PTSM injected at time 0 and ATSM injected at 10 min. according to the protocol optimized in (Rust and Kadrmas, 2006). Dynamic scanning was performed, starting with rapid sampling at the time of injection (5 second timeframes), followed by progressively slower sampling as the tracer distribution slowed and stabilized. At 10 minutes into the scan, the sequence with fast sampling was restarted for the ATSM administration. The complete temporal sampling schedule was: 12×5s, 6×10s, 6×30s, 5×60s, 12×5s, 6×10s, 6×30s, 5×60s, 5×120s, 1×300s, for a total scan duration of 35 min. 62Cu-PTSM and 62Cu-ATSM were prepared using a portable 62Zn/62Cu generator and tracer preparation kits obtained from Proportional Technologies (Houston, TX). Administered radioactivity for PTSM and ATSM were 4.7 ± 3.2 and 5.1 ± 2.8 mCi, respectively.

Figure 3.

Separate single-tracer scans were acquired, using the dual-tracer dynamic scanning protocol (top). The raw data from each scan were then combined to emulate a rapid dual-tracer scan (bottom), providing exactly paired single- and dual-tracer components permitting direct evaluation of the accuracy of the dual-tracer signal separation procedure. In practice, separate single-tracer scans would require 3hrs or longer to complete in order to wait for decay of the first tracer before imaging the second, whereas the rapid dual-tracer procedure can be completed in about 45 min.

II.B.1. Arterial Blood Sampling

Blood Samples (0.4–0.5 ml) were drawn from the AV shunt on a schedule similar to the scanning schedule for determination of the arterial input functions. Since PTSM and ATSM bind to serum albumin (Herrero et al., 1996, Lewis et al., 2002), the samples at roughly 1 min intervals were added to 1.0 ml octanol in test tubes and centrifuged to separate the freely available (octanol separated) and bound (pellet) fractions. Each sample was weighed and counted in a well counter soon after withdrawal, and corrections for radioactive decay were applied to recover time-activity curves for the whole-blood and freely-available arterial input functions for use with compartment modeling. For the actual-dual tracer scan, activity from both tracers was present in the blood once ATSM was administered. This could potentially complicate measurement of the input function for each tracer; however, at 10 min. after injection the octanol-extractable fraction of PTSM in the blood was only ~1%, with the remaining activity albumin bound. Thus, while the whole-blood activity contained contributions from each tracer, the octanol-extractable input function for ATSM was not significantly contaminated by the PTSM injection and could be recovered in a manner similar to that used in (Rust et al., 2006).

II.C. Data Processing

II.C.1. Raw-Data Emulation of Dual-Tracer Scanning

When two or more PET tracers are present, each tracer gives rise to indistinguishable 511 keV photon pairs. As far as the PET tomograph is concerned, there is no difference between having a single or multiple tracers present other than there being more positron-emitting radioactivity present. This radioactivity gives rise to true coincidences, scattered coincidences, and singles events leading to detector deadtime and random coincidences in the normal fashion. In order to emulate a dual-tracer scan, the raw prompts data, detector deadtime, normalization factors, attenuation factors, scatter and randoms estimates were first offloaded from the scanner. The emulated dual-tracer prompts were obtained by adding the prompts for both PTSM and ATSM. Likewise, the dual-tracer scatter estimate (used for scatter-correction) was also added. The detector normalization factors were identical for both scans, whereas the deadtime factors were slightly different and averaged for the emulated dual-tracer data. The randoms estimates (used for correcting the single-tracer scans) were also added, providing the corresponding randoms-correction data for the summed prompts data. In an actual dual-tracer scan, the detector deadtime would be somewhat lower than used here because photons from both source distributions would contribute to deadtime. Similarly, the randoms fractions would actually be higher than in our emulated data because randoms increase with the square of the singles countrate; however, the single-tracer randoms fractions were typically only ~5% (approaching 10% near the injection peaks). The difference in deadtime and randoms fraction between the emulated and an actual dual-tracer scan were relatively small, though this does represent a limitation of the dual-tracer emulation approach for obtaining paired-data for a gold standard. The emulated dual-tracer data had PTSM injected at time 0, ATSM at 10 min., and a total scan duration of 45 min. This required extrapolation of the final PTSM timeframe for an additional 10 min.; however, since the PTSM input had gone to zero and PTSM was at equilibrium for these times, simple radioactive decay was used to extend the PTSM data. Once combined, the emulated dual-tracer raw data were treated as an acquired dataset, reconstructed, and processed in the same manner as the single-tracer scan data as described below.

II.C.2. Reconstruction and Processing

For each scan, the raw data were reconstructed using four iterations of ordered-subsets expectation-maximization (OSEM) with twelve subsets, where the raw line-of-response (LOR) data were reconstructed directly and all corrections—including arc correction—were incorporated into the reconstruction matrix (LOR-OSEM, (Kadrmas, 2004)). No reconstruction filter was applied. Forty-seven regions-of-interest (ROIs), 4.5 ± 4.6 cm3, were drawn on ten tumor sites identified on the images, where multiple ROIs were used to characterize heterogeneity of larger tumors. Time-activity curves for each ROI and dataset were obtained, and the dual-tracer curves were processed by the signal separation procedure described below to recover both static and dynamic imaging measures for each tracer.

II.D. Dual-Tracer Signal Separation

The premise for dual-tracer signal separation is that the kinetic behavior of each tracer obeys certain constraints—and when staggered injections are used, these constraints provide sufficient information to recover the signal components due to each tracer from the overlapping portions of the time-activity curves. In this work, the kinetics of both PTSM and ATSM were assumed to follow compartment models with two tissue compartments and three rate parameters as shown in Fig. 4. The second compartment for each tracer had irreversible trapping, and radioactive decay was explicitly incorporated into the kinetic model to aid in signal separation. We emphasize that the primary purpose of the kinetic model is for dual-tracer signal separation, and not necessarily to quantify kinetic rate parameters (though rate parameters are obtained as a byproduct of the signal separation algorithm). When the recovered curves for each tracer are processed to obtain static imaging measures (e.g. standardized uptake value, SUV), we speculate that the level of accuracy required in the input functions will be greatly reduced as compared to usual applications of compartment models (since accurate quantification of the rate parameters would not be necessary).

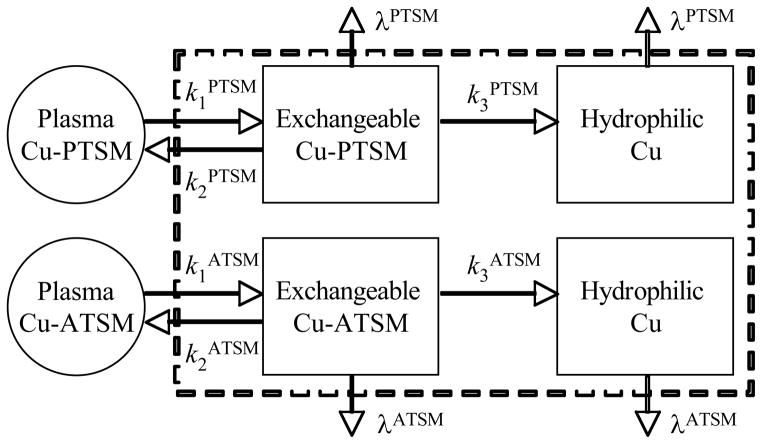

Figure 4.

Kinetic models with two tissue compartments, where the second had irreversible trapping, were used for both PTSM and ATSM. While these models may not precisely describe the kinetic of each tracer, they provide sufficient constraints for the signal-separation procedure to estimate and recover time-activity curve components for each tracer. Note that radioactive decay (λ) was explicitly incorporated into the kinetic models in order to aid with signal separation.

Under these compartment models, the activity concentration A(t) of the extravascular tissue compartments for each tracer can be written:

| (1) |

where {Ki} are the rate constants, λ is the radioactive decay constant, b(t) is the input function (concentration of freely exchangeable tracer in the blood), ⊗ is the convolution operator, and * is used to denote either PTSM or ATSM since the same model was used for each. For dual-tracer data, bATSM (t) was zero until ATSM was injected (t = 10 min). The activity concentration RDual(t) in a ROI measured by PET for dual-tracer data is modeled as:

| (2) |

where fB is the vascular fraction in the ROI and B(t) is the total activity concentration in the whole blood (including both tracers when present).

II.D.1. Signal Separation Algorithm

The signal separation algorithm begins by fitting eq. 2 to the dual-tracer time-activity curve. In this paper, the dual-tracer fits were performed via Levenberg-Marquardt minimization of chi-squared, and the code did not fit for delay or dispersion of the input function. The fitted parameters ( , fB )were analyzed and compared to those from single-tracer time-activity curves, and the fits were also used to predict the fraction of activity present for each tracer at each timepoint. These fractions were applied to the original (noisy) dual-tracer time-activity curve to split it into two recovered curves, one for PTSM and one for ATSM, which were then integrated from 20 to 25 minutes post-injection of each tracer to obtain SUVs.

II.E. Analysis

The use of the rapid dual-tracer technique represents a compression of two single-tracer measurements with some loss of information, but it does not represent a fundamentally different measurement technique. As such, the single-tracer imaging measures were treated as the standard for this evaluation, and the analysis tested whether the same results could be obtained from rapid dual-tracer imaging as from single-tracer imaging. Note that we do not approach the question of how accurately each tracer measured the target physiologic parameter. Linear regression analysis was used to compare the results from dual-tracer imaging to the separate, single-tracer standards. In addition, certain results were further analyzed by plotting the percent error versus the single-tracer standard—an analysis that is closely related to that of Bland-Altman (Bland and Altman, 1986), but treats the single-tracer measures as standard values and account for the fact that the error in part varies with the magnitude of the true parameter. Three sets of quantitative imaging measures were analyzed for each tracer: (i) the SUV obtained by integrating the time-activity curve, with decay correction, from 20 to 25 minutes post-injection; (ii) the net-influx parameter, knet = k1k3/(k2+ k3); and (iii) the individual rate parameters, k1–k3, obtained from the compartment model fits. The PTSM k1, knet, and SUV would have potential use for characterizing blood flow; whereas for ATSM k3 would be most closely related to hypoxia, with knet and SUV also potentially of interest (though consideration of flow-dependent tracer delivery may be necessary to obtain a direct measure of hypoxia). Combined, these imaging measures provide well-defined parameters for evaluating the performance of the signal separation algorithm and are used for that purpose in this paper.

III. RESULTS

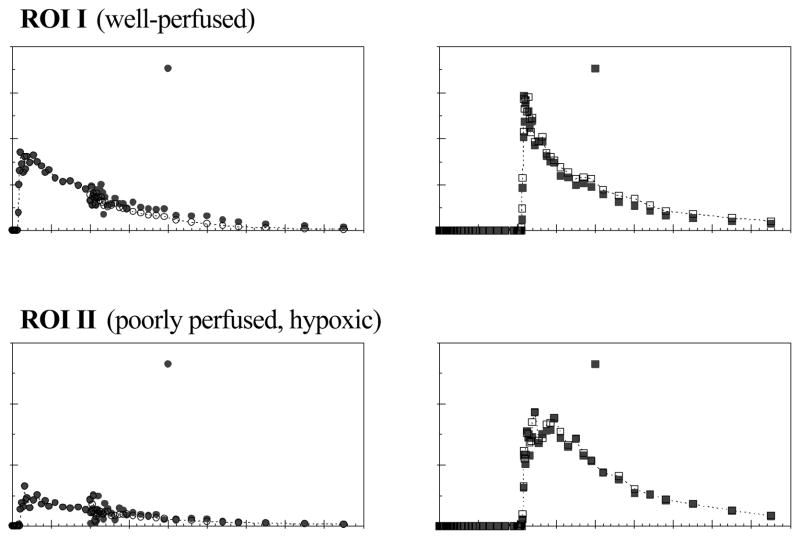

The experiments were successfully carried out for each of the four dogs reported on in this paper. Figure 5 shows example PTSM and ATSM images and time-activity curves for a 28.0 kg female Labrador retriever with histologically proven mammary papillary cystadenocarcinoma. A large tumor (I) is depicted with strong uptake of both tracers and relatively fast ATSM washout. A secondary tumor region is also evident (II) which has markedly lower tracer uptake but prolonged retention of ATSM, consistent with an under-perfused hypoxic region. The recovered time-activity curves from dual-tracer imaging for these two regions are presented in Fig. 6, where the standard single-tracer curves are also shown for comparison. There is excellent agreement between the recovered and standard curves, with greatest discrepancy in the noisy (5 sec.) timeframes at 10 min. corresponding to the bolus administration of ATSM.

Figure 5.

Example transaxial images of PTSM (left) and ATSM (right) showing two large tumors. Tumor I had significant delivery of both tracers with fast wash-out of ATSM, indicating it was well-perfused and oxygenated; whereas tumor II experienced limited delivery of each tracer but prolonged retention of ATSM, indicative of poorly-perfused and hypoxic tissue. The time-activity curves show the fits of the dual-tracer compartment model for regions-of-interest placed on each of these tumors.

Figure 6.

Recovered time-activity curves for the two tumor regions shown in fig. 5, where the separately-acquired single-tracer curves are shown as the gold standard. The recovered curves closely matched the single-tracer standards, demonstrating very good dual-tracer signal-recovery for this case. The high noise in the curves at 10 min. reflect the fast temporal sampling at the time when ATSM was injected.

Figure 7 shows scatter plots of two imaging measures, SUV and knet, which broadly characterize recovery of individual-tracer information from dual-tracer data. There was good agreement between SUVs recovered from dual-tracer data and those from single-tracer scans for both tracers, with Pearson’s correlation coefficients of 0.95 and 0.98 for PTSM and ATSM, respectively. Moderate bias in the slopes and intercepts of the regression lines, however, reflect some degree of incomplete signal-separation. The net uptake parameter for PTSM was accurately recovered for a large subset of the datapoints, though a number of outliers reduced the overall correlation to 0.70; further insight on PTSM signal recovery can be gleaned from the individual rate parameter results shown below. ATSM net uptake from dual-tracer data correlated strongly with single-tracer results (r = 0.92), though the slope of the regression line indicates some under-estimation of ATSM knet in general. These results demonstrate good overall recovery of these broadly characteristic imaging measures, though the moderate bias present suggests that improvements in the signal separation algorithm are warranted.

Figure 7.

Scatter plots of SUVs and net-uptake parameters recovered from dual-tracer versus separate single-tracer imaging for PTSM (left) and ATSM (right). Strong correlations were obtained, indicating that these broadly-characterizing imaging measures were successfully recovered from the dual-tracer signal-separation procedure. The slopes of the regression lines indicate moderate bias in the measures recovered from rapid dual-tracer data, which may potentially be resolved through further refinement of the dual-tracer signal-separation algorithm.

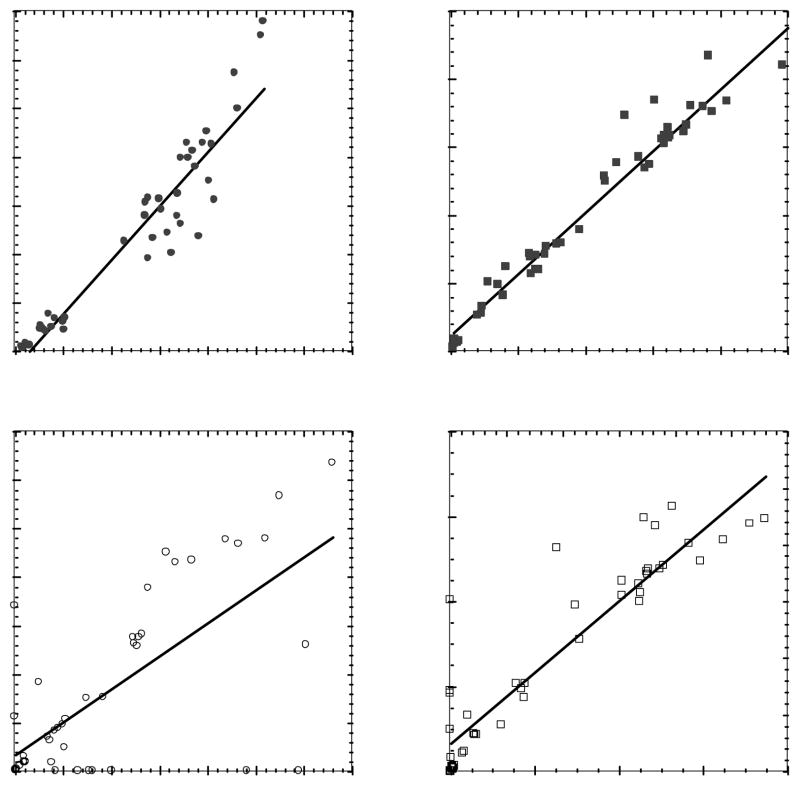

The results for the individual rate parameter estimates are shown in Fig. 8. Excellent agreement in k1 estimates was obtained for both tracers (r = 0.99), demonstrating that measurement of the wash-in phase of each tracer was not degraded by rapid dual-tracer imaging. This result was expected for PTSM since there was no ATSM activity present during the PTSM wash-in phase; however, the greatest overlap of activity occurs during the ATSM wash-in phase, and the result that ATSM k1 was accurately recovered is promising. The wash-out rate parameters (k2) for each tracer were also reasonably well-recovered (r = 0.87 for PTSM; 0.96 for ATSM). The PTSM retention parameter, k3, as recovered from dual-tracer imaging did not match the single-tracer results (r = 0.19), and this discrepancy was largely responsible for the outliers in the recovery of PTSM knet as discussed above. In part, the poor recoverability of PTSM k3 reflects a loss of signal information about PTSM after ATSM has been administered, though it is possible that somewhat better recovery of PTSM k3 might be obtained through advanced development of multi-tracer signal-separation algorithms. On the other hand, ATSM k3 was recovered from dual-tracer data with fair accuracy (r = 0.70), and in general low and high values of ATSM k3 were well-distinguished by dual-tracer imaging. This is of consequence since retention versus wash-out of ATSM distinguishes between hypoxic and normoxic tissues. In light of these results, further refinement and validation of the rapid dual-tracer method is recommended before clinical application should be considered.

Figure 8.

Scatter plots comparing dual-tracer versus single-tracer results for each individual rate parameter. Good-to-excellent recovery of k1 and k2 was observed for both tracers. PTSM k3 values recovered from dual-tracer imaging did not match those from separate single-tracer imaging, though a stronger correlation was observed between the recovered and standard ATSM k3 values. These data suggest that the initial wash-in and fast wash-out phases of each tracer are recovered from dual-tracer data more easily than later wash-out kinetics.

Recovery of several important imaging measures—SUVs for each tracer, PTSM k1, and ATSM k3—was further analyzed by evaluating the percent error in each measure as a function of the magnitude of the parameter as shown in Figure 9. Care should be taken in interpreting the percent errors for small values of each parameter, as large percent errors represent differences which are small in actual magnitude for such datapoints. All parameters other thank PTSM k1 showed moderate systematic dependence of the percent error upon the magnitude of the parameter (which is likewise reflected in the non-zero slopes of figures 7–8), though future improvements in multi-tracer signal-separation algorithms may potentially reduce these systematic biases. In an attempt to further characterize the error in dual-tracer estimates, we computed 95% confidence intervals on these data after omitting datapoints below an arbitrary threshold (0.1 for PTSM k1 and ATSM k3; 2.0 for SUVs). These thresholds were selected to avoid apparently high percent errors for datapoints with small magnitudes while retaining the datapoints having the most relevant magnitudes for quantification. (One interpretation of this is that low values were classified as “low” without need for quantification, whereas higher values were treated as quantitative estimates and contributed to the confidence interval calculations.) The percent errors of dual-tracer PTSM k1 estimates were largely independent of the magnitude of k1, and 95% of the dual-tracer estimates fell within −4.0% to +7.5% of the single-tracer values. Similarly, 95% confidence intervals for the other cases were: [−20.8%, +25.2%] for PTSM SUV, [−19.4%, +16.2%] for ATSM SUV, and [−47.9%, +62.5%] for ATSM k3.

Figure 9.

Percent error in dual-tracer imaging measures plotted as a function of the single-tracer standard values. The plots, closely related to Bland-Altman plots, reveal some systematic dependencies of the error in dual-tracer estimates with the magnitude of the parameter values. Further development of multi-tracer signal-separation algorithms may potentially reduce or eliminate these systematic effects.

The dual-tracer signal separation procedure was also applied to the actual dual-tracer scan performed in dog #4. Though a robust gold standard was not available for evaluating the accuracy of the recovered PTSM and ATSM data for this scan, the recovered curves were comparable to the single-tracer curves. Correlation coefficients for SUVs, k1, k2, and knet for dual-tracer versus single-tracer ranged from 0.84–0.96, where these results contain differences due to reproducibility of imaging the same tracer 4–5 hours apart as well as differences due to the dual-tracer technique. This scan demonstrated actual implementation of the dual-tracer technique in one animal.

IV. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Rapid multi-tracer PET has the potential to characterize multiple aspects of tumor physiology in a single scanning session, offering added information for tumor assessment, treatment selection and monitoring. Previous simulation studies have showed promise for recovering certain relevant imaging measures for individual tracers from rapid multi-tracer datasets (Ikoma et al., 2001, Koeppe et al., 1998, Koeppe et al., 2001; Kadrmas and Rust, 2005; Rust and Kadrmas, 2006). This paper provides experimental evaluation of one such rapid dual-tracer imaging technique with real physiologic tumor imaging data. The two tracers studied, 62Cu-PTSM and 62Cu-ATSM, provide a combination offering insight into the recoverability of tracer signals for an irreversibly trapped tracer (PTSM), and for a tracer which experiences either trapping or washout under different physiologic conditions (ATSM). This tracer combination also has potential clinical utility for dual-tracer assessment of blood flow and hypoxia in tumors, though the current study focused on the multi-tracer signal-recovery problem and did not address many of the issues that must be considered before applying such dual-tracer imaging clinically.

Dual-tracer signal-separation was accomplished using a parallel multi-tracer compartment-modeling algorithm. In order to directly study signal-separation performance, raw scanner data for each tracer were combined to produce exactly paired single- and dual-tracer data components. Static imaging measures (e.g. SUV) for each tracer were accurately recovered from dual-tracer data, with excellent correlations (r = 0.95 – 0.98) but some degree of bias. Significant kinetic information about each tracer was also recovered from the dual-tracer scans, though certain kinetic parameters (e.g. PTSM k3) were not recovered well. Overall, these results suggest that the initial wash-in and wash-out phases of each tracer are well recovered, and that higher-order kinetic information can be recovered to differing degrees depending on the degree of overlap and particular kinetics of the dataset being analyzed. The experimental results of this paper are consistent with previous simulation work, confirming that signal separation is possible in a physiologic model with realistic levels of model-mismatch between the kinetic models used for tracer signal-separation and the actual tracer kinetics. Overall, these results show promise for recovering certain imaging measures for each tracer, though tracer combinations and imaging protocols need to be carefully designed to ensure accurate recovery of the relevant imaging measures.

The multi-tracer signal-separation algorithm is based upon the premise that the kinetic behavior of each tracer obeys certain constraints, and with the use of staggered injections, these constraints provide sufficient information to recover certain signal components from each tracer. Some information about each tracer is irretrievably lost, however. A compartment-model based signal-separation algorithm was used here which required knowledge of the arterial input functions for each tracer. In practice, measurement of such input functions is tedious and would limit routine use of the multi-tracer technique at many sites. This limitation may potentially be overcome by development of signal-separation algorithms which do not require measurement of the arterial input function, or by using image-derived input functions. In addition, the present work only considered separation of time-activity curves for individual ROIs, and additional work is needed to address the problem of voxel-by-voxel image separation where additional challenges such as increased statistical noise and more variable kinetics will be encountered. Imaging performance may also differ for human tumors, which may have different growth rates and lower hypoxic fractions than the spontaneous canine tumors studied here. This work has demonstrated limited but effective dual-tracer PET imaging in a large animal tumor model, identifying good potential in the method as well as limitations in the technique which deserve further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Research Scholar Grant RSG-00-200-04-CCE from the American Cancer Society. The authors would like to thank Regan Butterfield, Melissa Brooks, Jonathan Engle, and Paul Christian for their help with the experiments, and Jeffrey Lacy at Proportional Technologies, Inc. for supplying the generators and tracer preparation kits used in this work. They would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments greatly improved the paper.

References

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruehlmeier M, Roelcke U, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM. Assessment of hypoxia and perfusion in human brain tumors using PET with 18F-fluoromisonidazole and 15O-H2O. J NuclMed. 2004;45:1851–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehdashti F, Mintun MA, Lewis JS, Bradley J, Govindan R, Laforest R, Welch MJ, Siegel BA. In vivo assessment of tumor hypoxia in lung cancer with 60Cu-ATSM. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:844–50. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower MA, Zweit J, Hall AD, Burke D, Davies MM, Dworkin MJ, Young HE, Mundy J, Ott RJ, McCready VR, Carnochan P, Allen-Mersh TG. 62Cu-PTSM and PET used for the assessment of angiotensin II-induced blood flow changes in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:99–103. doi: 10.1007/s002590000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujibayashi Y, Taniuchi H, Yonekura Y, Ohtani H, Konishi J, Yokoyama A. Copper-62-ATSM: a new hypoxia imaging agent with high membrane permeability and low redox potential. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1155–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes NG, Lacy JL, Nayak N, Martin CS, Dai D, Mathias CJ, Green MA. Performance of a 62Zn/62Cu generator in clinical trials of PET perfusion agent 62Cu-PTSM. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:309–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero P, Hartman JJ, Green MA, Anderson CJ, Welch MJ, Markham J, Bergmann SR. Regional myocardial perfusion assessed with generator-produced copper-62-PTSM and PET. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1294–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SC, Carson RE, Hoffman EJ, Kuhl DE, Phelps ME. An investigation of a double-tracer technique for positron computerized tomography. J Nucl Med. 1982;23:816–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikoma Y, Toyama H, Uemura K, Uchiyama A. Evaluation of the reliability in kinetic analysis for dual tracer injection of FDG and flumazenil PET study. In: SEIBERT JA, editor. Conf Rec IEEE Nuc Sci Symp and Med Imaging Conf. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kadrmas DJ. LOR-OSEM: statistical PET reconstruction from raw line-of-response histograms. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:4731–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/20/005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadrmas DJ, Rust TC. Feasibility of Rapid Multi-Tracer PET Tumor Imaging. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 2005 doi: 10.1109/TNS.2009.2026417. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppe RA, Ficaro EP, Raffel DM, Minoshima S, Kilbourn MR. Temporally overlapping dual-tracer PET studies. In: Carson RE, Daube-Witherspoon ME, Herscovitch P, editors. Quantitative Functional Brain Imaging with Positron Emission Tomography. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Koeppe RA, Raffel DM, Snyder SE, Ficaro EP, Kilbourn MR, Kuhl DE. Dual-[11C]tracer single-acquisition positron emission tomography studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1480–92. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtio K, Eskola O, Viljanen T, Oikonen V, Gronroos T, Sillanmaki L, Grenman R, Minn H. Imaging perfusion and hypoxia with PET to predict radiotherapy response in head-and-neck cancer. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:971–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtio K, Oikonen V, Gronroos T, Eskola O, Kalliokoski K, Bergman J, Solin O, Grenman R, Nuutila P, Minn H. Imaging of blood flow and hypoxia in head and neck cancer: initial evaluation with [(15)O]H(2)O and [(18)F]fluoroerythronitroimidazole PET. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1643–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JS, Herrero P, Sharp TL, Engelbach JA, Fujibayashi Y, Laforest R, Kovacs A, Gropler RJ, Welch MJ. Delineation of hypoxia in canine myocardium using PET and copper(II)-diacetyl-bis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone) J Nucl Med. 2002;43:1557–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JS, McCarthy DW, McCarthy TJ, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Evaluation of 64Cu-ATSM in vitro and in vivo in a hypoxic tumor model. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:177–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JS, Sharp TL, Laforest R, Fujibayashi Y, Welch MJ. Tumor uptake of copper-diacetyl-bis(N(4)-methylthiosemicarbazone): effect of changes in tissue oxygenation. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:655–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias CJ, Green MA, Morrison WB, Knapp DW. Evaluation of Cu-PTSM as a tracer of tumor perfusion: comparison with labeled microspheres in spontaneous canine neoplasms. Nucl Med Biol. 1994;21:83–7. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias CJ, Welch MJ, Perry DJ, Mcguire AH, Zhu X, Connett JM, Green MA. Investigation of copper-PTSM as a PET tracer for tumor blood flow. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1991;18:807–11. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(91)90022-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagamachi S, Czernin J, Kim AS, Sun KT, Bottcher M, Phelps ME, Schelbert H. Reproducibility of measurements of regional resting and hyperemic myocardial blood flow assessed with PET. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1626–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran JG, Krohn KA. Imaging hypoxia and angiogenesis in tumors. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43:169–87. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust TC, Dibella EV, Mcgann CJ, Christian PE, Hoffman JM, Kadrmas DJ. Rapid dual-injection single-scan 13N-ammonia PET for quantification of rest and stress myocardial blood flows. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:5347–62. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/20/018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusy TC, Kadrmas DJ. Rapid dual-tracer PTSM+ATSM PET imaging of tumour blood flow and hypoxia: a simulation study. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51:61–75. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/1/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Fujibayashi Y, Yonekura Y, Welch MJ, Waki A, Tsuchida T, Sadato N, Sugimoto K, Itoh H. Evaluation of 62Cu labeled diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) as a hypoxic tissue tracer in patients with lung cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2000;14:323–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02988690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]