Abstract

The present study was aimed at documenting medicinal plants used for the treatment of tuberculosis (TB) by the Bapedi traditional healers in three districts of the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Fifty two traditional healers from 17 municipalities covering Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts were interviewed between January and July 2011. Twenty one medicinal plant species belonging to 20 genera and 18 families were documented. The majority (61.9%) are indigenous and the rest are exotics, found near homes as weeds or cultivated in home gardens as ornamentals or food plants. Hyacinthaceae, Moraceae and Rutaceae families were the most represented families in terms of species numbers (9.5% each). Herbs and trees (38% each) constituted the largest proportion of the growth forms of the medicinal plants used. Tuberculosis remedies were mostly prepared from leaves (34%) followed by roots (21%). The therapeutic claims made on medicinal plants used to treat TB by the Bapedi traditional healers are well supported by literature, with 71.4% of the species having antimicrobial properties or have similar ethno medicinal uses in other countries. This study therefore, illustrates the importance of medicinal plants in the treatment and management of TB in the Limpopo Province, South Africa.

Keywords: Bapedi traditional healers, ethnobotanical survey, Limpopo Province, South Africa, tuberculosis

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (1998), tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Gangadharam (1993) noted that Mycobacterium tuberculosis mainly affects the lungs, causing lung tuberculosis (pulmonary tuberculosis). However, in some cases other parts of the body may also be affected leading to extrapulmonary tuberculosis (Sharma and Mohan, 2004). Tuberculosis spreads easily in overcrowded settings and in conditions of malnutrition and poverty (Pereira et al., 2005). It is mainly transmitted by exposure to Tubercle bacilli in airborne droplets from coughing or sneezing (Narwadiya et al., 2011). The common symptoms of TB are coughing, fever, hemoptysis, chest pain, fatigue and weight loss (Stanhope and Lancaster, 1996). In South Africa, patients with one or more of these signs or symptoms are considered “TB suspect” and must be further investigated for active TB disease according to the national TB guidelines (Department of Health, 2010).

In 1993, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared TB a global emergency because it killed more adults each year than any other infectious disease (The South African Tuberculosis Control Programme, 1998). Approximately one third of the world's population harbours TB infection (Zumla et al., 1999). An estimated 8.3 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths were attributed to this disease in 2000 (Jasmer et al., 2002). Developing countries have much higher incidences of TB than developed countries. A prevalence of 9.2% (Salami and Oluboyo, 2002) and fatality rate of 12% (Salami and Oluboyo, 2003) have been recorded in Nigeria. Mozambique was ranked among the 20 highest TB burden countries in the world, with an estimated 81 000 cases and an incidence rate of 436 per 100 000 people in 2002 (WHO, 2004). In Uganda 402 new cases of TB per 100 000 people were reported in 2005 (WHO, 2007). South Africa was ranked ninth in the list of twenty-two countries that were hardest hit by TB (WHO, 2005). Data from gold mines in South Africa, indicated that the overall TB incidence exceeded 4 000 per 100 000 population per year (Mallory et al., 2000). This incidence is high in the mines largely because of a high prevalence of silica dust exposure (Corbett et al., 2002). Amongst the twenty leading single causes of premature mortality in the North West Province, South Africa, TB was ranked fourth as responsible for death in all genders (Bradshaw et al., 2000); in the Mpumalanga Province, South Africa, TB was ranked sixth as cause of death of persons. Tuberculosis was ranked fifth as the cause of death for all races and both genders in the Limpopo Province, South Africa (Igumbor et al., 2003). Therefore, TB is a serious infectious disease in South Africa, requiring effective strategies and tools to control and manage it.

Tuberculosis control programmes currently emphasize the Directly Observed Treatment Short Course (DOTS) strategy, promoted by the World Health Organization and the International Union against TB and lung disease. South Africa adopted the WHO's DOTS strategy in all nine provinces (Department of Health, 2011). Key tenets of plan are standardized treatment of 68 months for all infectious patients; with directly observed therapy for at least the initial two months (WHO, 2005). However, previous studies by Needham et al. (1998) and Russell (2004) noted that rural patients often delay TB treatment, as they cannot afford to travel to treatment centres (DOTS clinics) daily to have a health worker watch them take their drugs. Kandel et al. (2008) found that of the 255 TB patients who came for treatment at Mbekweni Health Centre in the King Sabata Dalidyebo (KSD) district in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, 121 had interrupted their treatment. Reasons for interruption included change of living place, side effects of the drug, lack of knowledge about the treatment course, physical disability (either too sick or old) to collect treatment, clinic too far and drug not available in the clinic (Kandel et al., 2008). With the rapid increase in infection in sub Saharan Africa and due to the relatively high cost and limited access to synthetically derived drugs, communities in Africa have relied on traditional healers to treat infectious diseases (WHO, 2003). Traditional healers use medicinal plants as their primary source of medicine. Research done in Nigeria by Rinne (2001) revealed that local communities consult traditional healers on a regular basis because they are found within a short distance, are familiar with the patient's culture and the environment and the costs associated with treatments are negligible. Rural patients are also more dependent on traditional or folk medicinal healers for treatment of infectious diseases for a number of reasons, such as lack of access to modern medical facilities and clinging to traditional approaches (Hossan et al., 2010). Despite the increasing acceptance of traditional medicine in treating TB in South Africa (Buwa and Afolayan, 2009; Green et al., 2010), this indigenous knowledge on traditional remedies is not adequately documented. Therefore, the present study investigated and documented the medicinal plants used by the Bapedi traditional healers in the treatment and management of TB in Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts of the Limpopo Province, South Africa.

Materials and methods

The study area

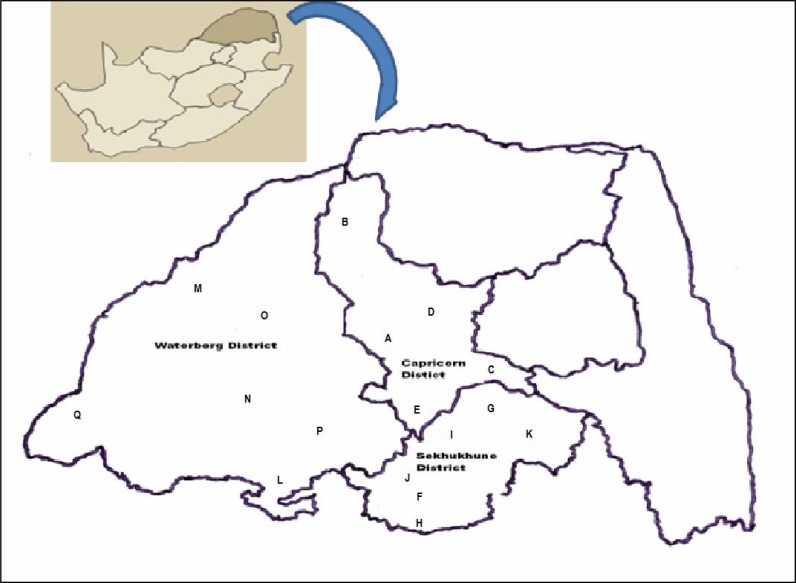

The present study was carried out in 17 local municipalities (Figure 1, Table 1), covering Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts. The majority of people in the study area belong to the Bapedi ethnic group, which is the largest group in the Limpopo Province of South Africa, comprising about 57% of the population (Lodge, 2005).

Figure 1.

Study area: Capricorn, Waterberg and Sekhukhune districts, Limpopo Province, South Africa. A to Q designates the involved municipalities.

Table 1.

Districts and local municipalities in which the study was undertaken

| Capricorn district | Sekhukhune district | Waterberg district |

| Aganang (A) | Alias Motsoaledi (F) | Bela-Bela (L) |

| Blouberg (B) | Fetakgomo (G) | Lephalale (M) |

| Lepelle-Nkumpi (C) | Groblersdal (H) | Modimolle (N) |

| Molemole (D) | Makhuduthamaga (I) | Mogalakwena (O) |

| Polokwane (E) | Marble Hall (J) | Mookgophong (P) |

| Tubatse (K) | Thabazimbi (Q) |

Data collection

The study was undertaken between January and July 2011. A total of 52 traditional healers (36 males and 16 females) were purposefully selected with the help of local administrators and elderly people from 17 municipalities within three districts of the Limpopo Province (Table 1, Figure 1). At least two traditional healers per local municipality participated in personal interviews which were conducted in Sepedi language. Verbal informal consent was obtained from each individual traditional healer who participated in the study and researchers adhered to the ethical guidelines of the International Society of Ethnobiology (http://www.ethnobiology.net). The aim of the investigation was explained to all participants. Data on plant names, the plant part(s) used, diagnosis of TB, mode of medicinal plant usage and administration were documented. All plant species mentioned by the traditional healers as important in the treatment and management of TB were collected, numbered, pressed and dried for identification. Each specimen included important parts such as leaves, stems, flowers and fruits where available. For small herbaceous plants, the whole plants were collected. Specimens were deposited for future reference at the Larry-Leach Herbarium (UNIN), University of Limpopo.

Results

Medicinal plants used to treat TB

Table 2 gives a list of the plant species used by the Bapedi traditional healers in Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts in the Limpopo Province to treat TB. The survey documented 21 plant species belonging to 20 genera and 18 families (Table 2). Of these, 13 species are indigenous to the Limpopo Province (61.9%), while eight species are exotics (38.1%), either naturalized as weeds or cultivated in home gardens as ornamentals or food plants. Families Hyacinthaceae, Moraceae and Rutaceae are represented by two species each, while the rest of the families are represented by one species each, as shown in Table 2. Mentha sp. could not be identified to species level due to non-availability of flowers and fruits at the time of collection. The most regularly used plant species in the study area to treat TB were Artemisia afra, cited by 15.4% of the traditional healers; Eucomis pallidiflora ssp. pole-evansii and Myrothamnus flabellifolius (11.5% each), Lippia javanica (9.6%) and Hypoxis hemerocallidea (7.7%). The other plant species were used either by one or two traditional healers.

Table 2.

Plant species used for the treatment of TB in Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts, Limpopo Province, South Africa. An asterisk (*) indicates that the taxon is known or believed to be exotic; and is cultivated in home gardens or naturalized in Limpopo Province, South Africa.

| Family, species names, voucher |

Habit | Part(s) used |

No. of citations in Districts |

Preparation, administration and dosage |

Reported uses in literature |

|||

| Capricorn | Sekhukhune | Waterberg | ||||||

| Agapathaceae | ||||||||

|

Agapanthus P.Beauv. SS340 |

inapertus | Herb | Tuber | _ | _ | 1 | Cooked for 10 minutes and one cup of extract is taken orally thrice a day. |

None found |

| Asteraceae | ||||||||

|

Artemisia afra Willd. SS223 |

Jacq. ex | Shrub | Leaves | _ | _ | 2 | Leaves cooked for 15 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

Asthma, bronchitis, colds, coughs and TB (Van Wyk and Gericke, 2000) |

| 2 | _ | _ | Leaves crushed, wrapped in newspaper and smoked twice a day or leaves burned in a hut and smoke inhaled twice a day |

|||||

| 1 | 1 | _ | Leaves put in hot water and steam inhaled thrice a day |

|||||

| Leaves; roots |

2 | _ | _ | Crushed leaves and roots are mixed with crushed leaves of Mentha spp., wrapped in newspaper and smoked thrice a day |

||||

| Cannabaceae | ||||||||

| *Cannabis sativa | L. SS24 | Herb | Leaves | 1 | - | - | Leaves macerated in warm water for 24 hours and one cup of decoction taken orally thrice a day |

Dry cough (Hutchings et al., 1996) |

| Caricaceae | ||||||||

| *Carica papaya | L. SS70 | Tree | Leaves | - | 1 | - | Leaves burned in a hut and smoke inhaled twice a day |

TB (Green et al. 2010) |

| Combretaceae | ||||||||

|

Combretum Schinz. SS440 |

hereroense | Shrub | Bark Seeds |

- - |

- 1 |

1 - |

Cooked for 20 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day Seeds burned in a hut and smoke inhaled twice a day |

Chest complaints and TB (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk 1962) |

| Gentianaceae | ||||||||

| Chironia baccifera | L. SS22 | Shrub | Roots | - | - | 1 | Cooked for 20 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

Diarrhoea and leprosy (Van Wyk and Gericke, 2000) |

| Hyacinthaceae | ||||||||

|

Eucomis pallidiflora ssp. pole-evansii Reyneke SS355 |

Baker. (N.E.Br.) |

Herb | Bulb | - | - | 6 | Cooked for 5–8 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

Chest complains, mental-illness and STIs (Moeng 2010) |

|

Merwilla plumbea Speta SS338 |

(Lindl.) | Herb | Bulb | - | - | 1 | Cooked for 25 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

Constipation, diarrhoea and nausea (Hutchings et al., 1996) |

| Hypoxidaceae | ||||||||

|

Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch., C.A.Mey. & Ave-Lall. SS115 |

Herb | Tuber | 2 | 1 | 1 | Cooked for 5–20 minutes and one cup of extract is taken orally thrice a day |

Arthritis, cold, flu, HIV/AIDS and wounds (Grierson and Afolayan, 1999) |

|

| Lamiaceae | ||||||||

| Mentha spp. SS477 | Herb | Leaves | 1 | Leaves wrapped and smoked twice a day |

None found | |||

| Moraceae | ||||||||

| *Ficus carica L. SS89 | Tree | Bark | - | - | 1 | Cooked for 10 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

None found | |

| *Ficus platypoda (Miq.) Miq. SS323 |

Tree | Roots | 1 | - | Cooked for 20 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

None found | ||

| Myrothamnaceae | ||||||||

|

Myrothamnus flabellifolius (Sond.) Welw. SS111 |

Shrub | Whole plant |

2 | - | Burned in hut and smoke inhaled four times a day |

TB (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962) | ||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | Cooked for 5–15 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

|||||

| Myrtaceae | ||||||||

| *Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. SS401 |

Tree | Leaves; roots |

1 | - | 1 | Cooked for 5–20 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

Asthma, cough, diarrhoea and sore throat (Abubakar, 2010) |

|

| Pteridaceae | ||||||||

|

Pellaea calomelanos (Sw.) Link SS25 |

Fern | Roots | - | - | 1 | Cooked for 15 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

None found | |

| Rosaceae | ||||||||

| *Eriobotrya japonica Lindl. SS311 |

Tree | Roots | - | - | 1 | Cooked for 10 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

None found | |

| Rutaceae | ||||||||

| *Citrus lemon (L.) Burm. f. SS480 |

Tree | Leaves | 1 | - | 1 | Crushed leaves, wrapped in newspaper and smoked thrice a day |

Cough, flu and fever (Maroyi, 2011) |

|

|

Zanthoxylum capense (Thunb.) Harv. SS511 |

Tree | Roots | - | - | 1 | Burned in a hut and smoke inhaled twice a day |

Chronic cough (Bryant, 1966) |

|

| - | - | 1 | Cooked for 10 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day |

|||||

| Salicaceae | ||||||||

|

Salix mucronata SS21 |

Thunb. | Tree | Seeds; fruits |

- | - | 1 | Six raw fruits taken orally thrice a day |

Fever, rheumatism and wound dressing |

| - | 1 | - | Fruits and seeds ground into powder and five table spoons taken orally with warm water thrice a day |

(Eldeen and Van Staden, 2007) | ||||

| Verbenaceae | ||||||||

|

Lippia javanica Spreng. SS180 |

(Burm. f.) | Herb | Leaves | - - |

1 - |

2 2 |

Cooked for 5 minutes and one cup of extract taken orally thrice a day Leaves put in hot water and steam inhaled thrice a day |

Respiratory complaints (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962); TB (Green et al., 2010) |

| Zingiberaceae | ||||||||

| *Aframomum melegueta (Rox.) K.Schum. SS331 |

Herb | Roots | - | - | 1 | Cooked for 10 minutes and one cup of extract is taken orally thrice a day |

Chest congestion, cough and TB (Betti, 2004; Gill, 1992) |

|

Diagnosis

Bapedi traditional healers diagnosed TB based on patient's signs and symptoms. Before starting the treatment, patients were observed carefully and asked about the signs and symptoms of TB (Table 3). The Bapedi traditional healers assess the treatment outcomes in patients, mainly by patient feedback and disappearance of TB signs and symptoms. Any patient who presented one or a combination of the signs and symptoms given in Table 3 was considered by the Bapedi traditional healers as TB “suspect”. Blood in the sputum was the most commonly cited diagnostic criterion, followed by a prolonged cough. After diagnosis, the healers prescribed and prepared the medication.

Table 3.

Criteria used by the Bapedi traditional healers to diagnose TB

| Signs and symptoms | No. of traditional healers* |

| Blood in the sputum | 19 |

| Prolonged cough | 14 |

| Weight loss | 4 |

| Swelled face and blood in the sputum | 2 |

| Chest pain and breathlessness | 1 |

Some traditional healers provided more than one diagnostic criterion

Growth forms, plant parts used and methods of application

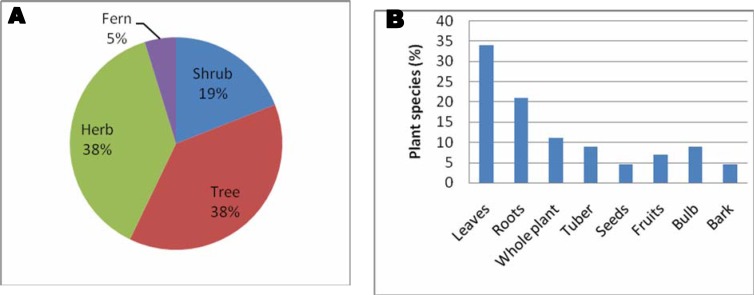

An analysis of the medicinal species used by the Bapedi traditional healers to treat TB, revealed that herbs and trees constituted the largest proportion of growth forms with 38% each, followed by shrubs with 19% as shown in Figure 2A. Pteridophytes were represented by a single fern species, Pellaea calomelanos (Table 2). The plant parts used for herbal preparations were the roots, bulbs, tubers, leaves, bark, seeds, and fruits. The leaves were the most commonly used (34%), followed by roots (21%), whole plant (11%), bulbs and tubers (9% each), fruits (7%), bark and seeds with 4.5% each (Figure 2B). The whole plant was administered for herbaceous plant species. 28 TB remedies (96.6%) were prepared from single species (Table 2). However, crushed leaves and roots of Artemisia afra were mixed with crushed leaves of Mentha spp. and smoked thrice a day. Methods of herbal administration included oral, smoking and inhalation. Extracts or decoctions were prescribed orally with a metal cup (250 ml). The fruits of Salix mucronata were taken orally as raw thrice a day (Table 2). Traditional healers also burnt leaves of Artemisia afra, Carica papaya (leaves), Combretum hereroense (seeds), Myrothamnus flabellifolius (whole plant) and roots of Zanthoxylum capense in the consultation hut and patients inhaled the smoke twice to four times a day (Table 2). Leaves of Artemisia afra and Lippia javanica were deposited in a basin full of hot water and patients inhaled the resultant steam with their heads covered with a blanket. Crushed leaves of Artemisia afra, Citrus lemon and Mentha sp. were wrapped in a newspaper and smoked twice or thrice a day. All herbal preparations were taken for two weeks to a month depending on patient's response to the medication, and individual healer's experience with TB treatment and management.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of the plants used for the treatment and management of TB in the Limpopo Province. A. Growth habit represented in pie diagram and (B) plant part(s) used represented in bar chart.

Discussion

A large proportion of the plant species documented in this study have been validated through phytochemical and pharmaceutical research. Some, though not evaluated for their efficacy are used to treat TB and related diseases in South Africa and other parts of the world. For example Lippia javanica and Carica papaya are used by the VhaVenda traditional healers of the Limpopo Province, South Africa to treat TB (Green et al., 2010). Leaves of Lippia javanica are used extensively in southern Africa to treat respiratory complaints (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962). Likewise, Cannabis sativa leaves are smoked by Zulu people to treat dry cough (Hutchings et al., 1996), while the root of Zanthoxylum capense is a remedy for chronic coughs (Bryant, 1966). Similarly, Aframomum melegueta is documented as a remedy for tuberculosis, cough and chest congestion in Cameroon (Betti, 2004) and Nigeria (Gill, 1992). Eldeen and Van Staden (2007) documented anti-bacterial activity of Salix mucronata. Leaf extract of Eucalyptus camaldulensis inhibited the growth of Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia and Staphylococcus aureus (Abubakar, 2010). Combretum hereroense is reported as a remedy for TB and chest complaints in southern and eastern Africa (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962). Extracts from this species have shown some activity against Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia and Staphylococcus aureus (Alexander et al., 1992). To the best of our knowledge Eriobotrya japonica and Merwilla plumbea are reported in this study for the first time as remedies for TB in South Africa; but they are widely used to treat an array of other ailments including boils, impotency, infertility, sores and wounds (Van Wyk et al., 2009). Furthermore, the use of Eriobotrya japonica by the Bapedi traditional healers as TB remedy is consistent with its application in Chinese ethno medicine (Parihar et al., 2011). The people of Muroto and Susaki cities in Japan (Nishioka et al., 2002) and traditional healers in Korea (Ito et al., 2000), use this species as a remedy for cough, an ailment either directly or indirectly associated with TB (Zaman et al., 2006). Although no known reports exist for Merwilla plumbea as a TB remedy in South Africa, its bulb extract demonstrated anti-bacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus (Verschaeve and Van Staden, 2008).

The wide utilization of Artemisia afra by the Bapedi traditional healers in this study to treat TB is in partial agreement with findings of Van Wyk and Gericke (2000), who noted its use as a remedy for respiratory disorders (asthma, bronchitis, colds, coughs and whooping cough). Leaf extract of Artemisia afra has been reported by Buwa and Afolayan (2009) as active against Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Mycobacterium A+ strain. No anti-bacterial activity has been documented so far for Eucomis pallidiflora ssp. pole-evansii, a widely used TB remedy in the Limpopo Province. But anti-bacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus have been demonstrated by two closely related Eucomis comosa and Eucomis humilis (Du Toit et al., 2005). A study by Grierson and Afolayan (1999) noted wide use of Hypoxis hemerocallidea by Xhosa healers to treat wounds and alleviate arthritis, cold, flu and HIV/AIDS. According to Lall and Meyer (2001), individuals infected with HIV/AIDS are also susceptible to TB and often develop this disease before other manifestations become apparent. Pharmacological activities of Hypoxis hemerocallidea extracts have been documented by Nicoletti et al. (1992), Mills et al. (2005), Ojewole (2006) and Muwanga (2006). The uses of Myrothamnus flabellifolius as a TB remedy and other related ailments are well documented in South Africa (Watt and Breyer-Brandwijk, 1962; Mabogo, 1990; Hutchings et al., 1996) and Zimbabwe (Gelfland et al., 1985).

Conclusion

This study shows that local communities in the Limpopo Province are still dependant on traditional medicines to treat and manage TB. The documented medicinal plants used by the Bapedi traditional healers reflect a rich ethno medicinal knowledge in the province. These results strengthen the firm belief that traditional medicines are readily accessible and still play an important role in meeting the basic health care of many people in developing countries. Some of the medicinal plants documented in this study can provide a treatment option that is readily accessible and affordable to TB patients in the Limpopo Province, the rest of South Africa and also beyond the national boundaries. The literature search has also shown that a large proportion of medicinal plants prescribed to TB patients by the Bapedi traditional healers are effective against several infectious pathogens. This is an indication of the potential value of the documented medicinal plants as sources of compounds needed for the development of plant derived anti-tuberculosis drugs.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the traditional healers in the Capricorn, Sekhukhune and Waterberg districts of the Limpopo Province, South Africa for sharing their knowledge on herbal medicines used to treat and manage TB. Anonymous reviewer is thanked for constructive comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Abubakar E-MM. Antibacterial potential of crude leaf extracts of Eucalyptus camaldulensis against some pathogenic bacteria. Afr J Plant Sci. 2010;4:202–209. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander DM, Bhana N, Bhika KH, Rogers CB. Antimicrobial testing of selected plant extracts from Combretum species. S Afr J Sci. 1992;88:342–344. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betti JL. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants among the Baka pygmies in the Dja Biosphere Reserve, Cameroon. Afr Stud Monogr. 2004;25:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradshaw D, Nannan N, Laubscher R, Groenewald P, Joubert J, Nojilana B, Norman R, Pieterse D, Schneider M. South African National Burden of Disease Study 2000: Estimates of Provincial Mortality. Pretoria: Government Printer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant AY. Zulu Medicine and Medicine Men. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buwa LV, Afolayan AJ. Antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants used for the treatment of tuberculosis in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:6683–6687. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbett EL, Churchyard GJ, Charalambous S, Samb B, Moloi V, Clayton TC, Grant AD, Murray J, Hayes RJ, De Cock KM. Morbidity and mortality in South African gold miners: impact of untreated disease due to human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1251–1258. doi: 10.1086/339540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health, author. Tuberculosis Strategic Plan for South Africa, 2007–2011. Pretoria: Government Printer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health, author. Guidelines for Tuberculosis Preventive Therapy Among HIV Infected Individuals in South Africa. Pretoria: Government Printer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Toit K, Elgorashi EE, Malan SF, Drewes SE, Van Staden J, Crouch NR, Mulholland DA. Anti-inflammatory activity and QSAR studies of compounds isolated from Hyacinthaceae species and Tachiadenus longiflorus Griseb. (Gentianaceae) Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:2561–2568. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eldeen IMS, Van Staden J. Antimycobacterial activity of some trees used in South African traditional medicine. S Afr J Bot. 2007;73:248–251. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangadharam PRJ. Drug resistance in tuberculosis. In: Reichmann LB, Hershfield ES, editors. Tuberculosis: A Comprehensive International Approach. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 293–328. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelfand M, Mavi S, Drummond RB, Ndemera B. The Traditional Medical Practitioner in Zimbabwe: His Principles of Practice and Pharmacopoeia. Gweru: Mambo Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill LS. Ethnomedicinal Uses of Plants in Nigeria. Nigeria: University of Benin Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green E, Samie A, Obi CL, Bessong PO, Ndip RN. Inhibitory properties of selected South African medicinal plants against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;130:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grierson DS, Afolayan AJ. An ethnobotanical study of plants used for the treatment of wounds in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;67:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(99)00082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hossan S, Hanif A, Agarwala B, Sarwar S, Karim M, Rahaman MT-U, Jahan R, Rahmatullah M. Traditional use of medicinal plants in Bangladesh to treat urinary tract infections and sexually transmitted diseases. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2010;8:61–74. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutchings A, Scott AH, Lewis G, Cunningham A. Zulu Medicinal Plants. An Inventory. Pietermarizburg, South Africa: University of Natal Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Igumbor EU, Bradshaw D, Laubscher R. Mortality Profile From Registered Deaths for the Limpopo Province, South Africa 1997–2001. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council, University of Venda; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito H, Kobayashi E, Takamatsu Y, Li SH, Hatano T, Sakagami H, Kusama K, Satoh K, Sugita S, Shimura S, Itoh Y, Yoshida T. Polyphenols from Eriobotrya japonica and their cytotoxicity against human oral tumor cell lines. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 2000;48:687–693. doi: 10.1248/cpb.48.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jasmer RM, Nahid P, Hopewell PC. Clinical practice: latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1860–1866. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp021045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kandel TR, Mfenyana K, Chandia J, Yogeswaran P. The prevalence of and reasons for interruption of antituberculosis treatment by patients at Mbekweni Health Centre in the King Sabata Dalidyebo (KSD) district in the Eastern Cape Province. S Afr Fam Prac. 2008;50:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lall N, Meyer JJM. Inhinition of drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by diospyrin, isolated from Euclea natalensis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;78:213–216. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lodge T. Provincial government and state authority in South Africa. J S Afr Stud. 2005;31:737–753. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mabogo DEN. The ethnobotany of the VhaVenda. University of Pretoria; 1990. MSc Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mallory KF, Churchyard GJ, Kleinschmidt I, De Cock KM, Corbett EL. The impact of HIV infection on recurrence of tuberculosis in South African gold miners. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:455–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maroyi A. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used by the people in Nhema communal area, Zimbabwe. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mills E, Cooper C, Seely D, Kanfer I. African herbal medicines in the treatment of HIV: Hypoxis and Sutherlandia. an overview of evidence and pharmacology. Nutr J. 2005;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moeng ET. The impact of muthi shops and street vendors on medicinal plants of the Limpopo Province. Mankweng: University of Limpopo; 2010. MSc Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muwanga C. An assessment of Hypoxis hemerocallidea extracts, and actives as natural antibiotic, and immune modulation phytotherapies. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape; 2006. MSc. Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narwadiya SC, Sahare KN, Tumane PM, Dhumne UL, Meshram VG. In vitro anti-tuberculosis effect of vitamin C contents of medicinal plants. Asian J Exp Biol Sci. 2011;2:151–154. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Needham DM, Godfrey-Faussett P, Foster SD. Barriers to tuberculosis control in urban Zambia: the economic impact and burden on patients prior to diagnosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:811–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicoletti M, Gallefi C, Messana L, Marini-Bettolo GB. Hypoxidaceae: medicinal uses and the norlignan constituents. J Ethnopharmacol. 1992;36:95–101. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(92)90008-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishioka Y, Yoshioka S, Kusunose M, Cui T, Hamada A, Ono M, Miyamura M, Kyotani S. Effects of extract derived from Eriobotrya japonica on liver function improvement in rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:1053–1057. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojewole J. Antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic properties of Hypoxis hemerocallidae Fisch. & C.A.Mey (Hypoxidaceae) corm (“African potato”) aqueous extract in mice and rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parihar M, Chouhan A, Harsoliya MS, Pathan JK, Banerjee S, Khan N, Patel VM. A review: cough and treatments. Int J Nat Prod Res. 2011;1:9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pereira M, Tripathy S, Inamdar V, Ramesh K, Bhavsar M, Date A, Iyyer R, Acchammachary A, Mehendale S, Risbud A. Drug resistance pattern of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in seropositive and seronegative HIV-TB patients in Pune, India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;121:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rinne E-M. Water and healing: experiences from the traditional healers in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Nor J Afr Stud. 2001;10:41–65. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell S. The economic burden of illness for households in developing countries: a review of studies focusing on malaria, tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salami AK, Oluboyo PO. Hospital prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis and co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus in Ilorin: a review of nine years (1991–1999) West Afr J Med. 2002;21:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salami AK, Oluboyo PO. Management outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis, a nine year review in Ilorin. West Afr J Med. 2003;22:114–119. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v22i2.27928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharma SK, Mohan A. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Ind J Med Res. 2004;120:316–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stanhope M, Lancaster J. Community Health Nursing: Promoting Health of Aggregates, Families and Individuals. London: Blackwell Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.The South African Tuberculosis Control Programme, author. Tuberculosis: A Training Manual for Health Workers. Pretoria: Department of Health Directorate of Tuberculosis Control; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Wyk B-E, Van Oudtshoorn B, Gericke N. Medicinal Plants of South Africa. Pretoria: Briza Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Wyk BE, Gericke N. People's Plants: A Guide to Useful Plants of Southern Africa. Pretoria: Briza Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verschaeve L, Van Staden J. Mutagenic and antimutagenic properties of extracts from South African traditional medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.06.007. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037887410800305X - aff3. Delete http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037887410800305X - aff3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watt JM, Breyer-Brandwijk MG. The Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Southern and Eastern Africa. London: Livingstone; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 49.WHO, author. WHO (World Health Organization). Tuberculosis. World Health Organization; 2007. WHO, Fact Sheet No. 104. [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO, author. WHO (World Health Organization). Addressing Poverty in TB Control, Options for National TB Control Programmes. World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 51.WHO, author. WHO (World Health Organization). Global Tuberculosis Control: Surveillance, Planning, Financing. World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.WHO, author. WHO (World Health Organization). Risk Factors for Tuberculosis. The World Health Report. World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.WHO, author. (World Health Organization). WHO: Global Tuberculosis Programme. Global Tuberculosis Control. WHO Report. World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaman K, Yunus M, Aarifeen SE, Baqui AH, Sack DA, Hossain S, Rahim Z, Ali M, Banu S, Islam MA, Begum B, Begum V, Breiman RF, Black RE. Prevalence of sputum smear-positive tuberculosis in a rural area in Bangladesh. Epidemiol Infect. 2006;134:1052–1059. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zumla A, Mwaba P, Squire SB, Grange JM. The tuberculosis pandemic: which way now? J Infect. 1999;38:74–79. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(99)90072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]