Abstract

Gunnera perpensa L. (Gunneraceae) is a medicinal plant used by Zulu traditional healers to stimulate milk production. The effect of an aqueous extract of the rhizome of the plant on milk production in rats was investigated. Female lactating rats that received oral doses of the extract of G.perpensa significantly (p<0.05) produced more milk than controls. The plant extract did not however, significantly influence the levels of prolactin, growth hormone, progesterone, cortisol, ALT, AST and albumin in the blood. The mammary glands of rats treated with the extract showed lobuloalveolar development. The extract (0.8 µg/ml) was also found to stimulate the contraction of the uterus and inhibit (23%) acetylcholinesterase activity. The cytotoxicity of the extract (LC50) to two human cell lines (HEK293 and HepG2) was 279.43 µg/ml and 222.33µg/ml, respectively. It is inferred that the plant extract exerts its activity on milk production and secretion by stimulating lobuloalveolar cell development and the contraction of myoepithelial cells in the alveoli. It is concluded that Gunnera perpensa contains constituents with lactogenic activity that apparently contribute to its effectiveness in folk medicine.

Keywords: Gunnera perpensa, Gunneraceae, cytotoxicity, lactation, muscle contractility

Introduction

Milk is a food of great biological significance for mammals from the moment they are born; it is accredited by the quantity and quality of nutrients it contains (William and Ruth, 2005). Alveoli are the primary components of a mature mammary gland lined with milk-secreting cuboidal cells and surrounded by myoepithelial cells. The myoepithelial cells can contract under the stimulation of oxytocin thereby excreting milk secreted from alveolar units into the lobule lumen toward the nipple, where it collects in sinuses of the ducts. As the infant begins to suck, the oxytocin-mediated (oxytocin) “let down reflex” ensues and the mother's milk is secreted (Watson & Khaled, 2008).

The key hormone that initiates milk biosynthesis is prolactin (Vonderhaar, 1987), which exerts a direct effect on the mammary gland through prolactin receptors. Thus, when a mother has low prolactin levels, milk supply may be affected. The drugs used for increasing milk supply work by blocking dopamine—a major inhibitor of prolactin (Redgrave and Kevin, 2006). These drugs do not work in all women and would therefore not increase milk production in a woman who already has normal or high prolactin levels (Brown et al, 2000). Drugs that are used to stimulate milk production are also known to cause severe depression in mothers (Gabay, 2002). There is, therefore, the need to search for alternative medicine.

Traditional healing has been the main form of medicine to cure diseases and providing primary healthcare to rural people. Traditional healers use various herbal preparations in addressing various illnesses. Some plants that affect milk production either by stimulating prolactin or mammary gland development (Lompo-Ouedraogo et al, 2004) have been reported. Ethnobotanical survey of traditional healers around Kwa-Zulu Natal revealed Gunnera perpensa L (uGobho Zulu name) to be one of the many plants used to stimulate lactogenic activity. Decoction prepared from it is also used to remove excess fluid from the body and to remove placenta after birth. Biological and pharmacology studies of various extracts and isolated compounds from the plant confirmed antibacterial activities (Drewes et al, 2005; Buwa and van Staden, 2006; Ndhlala et al, 2009), antifungal activity (Buwa and van Staden, 2006; Ndhlala et al, 2009), antimicrobial activity (Nkomo and Kambizi, 2009), antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory (Nkomo et al, 2010), antioxidant activity (Simelane et al, 2010) and uterine contractile activity (Khan et al, 2004). Considering the extensive utilization of G. perpensa in Zulu traditional medicine, the present study was undertaken to investigate the rhizomes of G.perpensa for its effect on milk production in lactating rats.

Materials and methods

Unless otherwise stated, all the chemicals used were of analytical grade purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd (Steinheim, Germany).

Plant material

Fresh rhizomes of G. perpensa L. (Gunneraceae) were collected from Kwa-Dlangezwa area in the city of Umhlathuze, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, at the flowering stage in March, 2009 under the authority of indigenous knowledge system (IKS), University of Zululand. The plant was identified by Mrs. N.R.Ntuli, Department of Botany University of Zululand, Kwa-Dlangezwa. A voucher specimen was deposited at the University Herbarium [Simelane, MBC/01(ZULU)].

Preparation of aqueous extract

The dried plant material was extracted (1:5 w/v) with water for 24 h by incubating the mixture on an orbital shaker (150 rpm, room temperature). The extracts were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and the aqueous filtrate freeze-dried. The dried extract was reconstituted in water before use.

Effect of oral treatment with G.perpensa extract on milk production

Approval for experimental procedures was obtained from the Research Animal Ethic Committee, University of Zululand. Virgin female rats (Sprague-Dawley) weighing 200–250 g (10 weeks old) were obtained from animal house of Department of Biochemistry and Microbiology at the University of Zululand. The animals were housed with male rats in a plastic cage under standard laboratory condition (25°C–29°C with 12 h dark/ light cycle) so that they can become pregnant. They were fed with food and water ad libitum. Following birth, the litters' weights were recorded and culled to 6 litters per dam. The lactating rats were randomly divided into four main groups (control, metoclopramide-treated, extract-treated and extract plus dopamine-treated groups). Control, metoclopramide-treated and extract plus dopamine treated groups consisted of five rats each (n=5), while the extract-treated group was subdivided into three sub-groups of five rats each. Accordingly, the extract was administered in three different doses: 400, 800 and 1600 mg.kg−1. The extract and the drugs (5mg.kg−1) were administered orally except for dopamine (5 µg.kg−1) which was injected intraperitoneally. All groups received the respective extract and the drug for six days starting from day 4 to day 9 of lactation.

Milk production was estimated 18 h and 23 h after gavage. Milk yield and body weight of dams and weight gain of pups were measured (Sampson & Jansen, 1984) each day. Every day during the study period, the pups were weighed at 07h00 (w1) and subsequently isolated from their mother for 4 h. At 11h00, the pups were weighed (w2), returned to their mother and allowed to feed for 1 h. At 12h00, they were weighed (w3) again. Milk yield 18h after the gavage was estimated as w3- w2. Daily milk yield was corrected for weight loss due to metabolic processes in the pup (respiration, urination and defecation) during suckling. The value used was (w2- w1)/4. This value was then multiplied by the number of suckling hours per day and added to the daily suckling gain. Daily weight gain of pups was calculated from the pup weight at w2. The same procedure was followed for 23 h.

Blood analysis

On day 10 the animals were killed by decapitation. The blood was obtained by cardiac puncture and it was analyzed at the Lancet laboratories (Richards Bay Hospital) using standard pathology procedures for the measurements of prolactin, progesterone, insulin, growth hormone, cortisol, total bilirubin, conjugated bilirubin, albumin, total protein, urea, creatinine, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP).

Histology of mammary tissue

Inguinal mammary glands were removed and were stored in 40% formalin. Histology studies were carried out at the Vet Diagnostix Laboratories (Pietermaritzburg) by qualified pathologist having no prior knowledge to which group they belonged. This method allowed for unbiased description of the histological lesions which were present or absent in the samples.

Uterus contractility

Twelve female non-pregnant rats weighing 200–250 g (12 weeks old) were injected with stilbestrol (12 mg/kg) 24hrs before they were sacrificed. The abdomens were opened and the two uterine horns of approximately equal lengths (2–3 cm long) from each rat were exposed avoiding stretching of uterine smooth muscles. Silk threads were tied at both top and bottom of the uterine strip. The two uterine horn segments were separately suspended in 30-ml organ bath containing de Jalon's physiological solution maintained at 32±1°C with 95% O2 / 5% CO2. Two uterine horn strips were always set-up at a time (one used as the ‘test', and the other one used as the ‘control’ preparation) to allow for changes in tissue sensitivity. Each uterine horn strip was subjected to an applied resting tension of 1 g, and thereafter was allowed to equilibrate for 45–60 min, during which time the tissues were bath every 15 min with de Jalon's physiological solution (DJS). After an equilibration period, graded concentrations of G. perpensa extract or oxytocin were added to the organ bath cumulatively to generate a cumulative concentration-response curve. The extract and oxytocin were administered to the uterine horn preparations for 5 minutes. Changes in tension developed by the uterine horn preparations were recorded isometrically by force-displacement transducers (TR1201 Isometric Transducer AD Instruments MLT201, Letica, Conella, Barcelona, Spain) and computed on PowerLab system (Ad Instruments, Power lab 4/25, AD Instruments Inc, Bella Vista, Australia). In tissues spontaneously contracting, responses were measured by terminating the difference in peak tension that developed before (15 min before extract or oxytocin addition) and after extract or oxytocin addition to the organ bath (Moustafab et al, 1999).

Oxytocin (0.2 µg/ml) was used as standard. All assays were repeated six times and the mean ± S.E reported. The percentage contractility effect of G. perpensa extract of each parameter was calculated as follows:

% contractility = {(max - min force)/ Max force} × 100

Where, max is the maximum force and min is the minimum force

Effect of extract on Acetylcholine esterase activity

Acetylcholinesterase activity was estimated using acetylthiocholine iodide as substrate following the method of Ellman et al (1961) with some modifications. The fish brain was homogenised in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 8 and diluted with sufficient amount of phosphate buffer to obtain 20 mg of brain tissue per 1 ml of buffer. The tissue was centrifuged at 1000 x g for 20 min and supernatant was analyzed immediately. Supernatant (0.4 ml) was pipetted into a set of test tubes and 2.6 ml phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) and 1.0ml of different concentrations (0–5 mg/100ml) of plant extract added. Thereafter 0.1 M of, 5,5'-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) reagent (100 µl) was added and mixed well. 5 mM s-acetyl- thiocholine iodide (ASChI) solution (20 µl) was added quickly and mixed well. The absorbance was recorded at 60 second intervals at 412 nm (BiotekELx 808). The reaction rate (R) was calculated in units of changes in absorbance per minute from the formula: R=574xA/C; where R = rate of µmoles, of substrate hydrolysed/min/g brain tissue, A=change in absorbance per min and C=original concentration of brain tissue (mg/ml) in the homogenate (this value remains constant at 20 mg/ml throughout the study). The percentage inhibition was calculated as: % inhibition= {(Ro − R1)/Ro × 100} where, Ro is the reaction rate of the control and R1 is the reaction rate in the presence of the extract. The inhibitory concentration providing 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated from the graph of percentage inhibition against G.perpensa extract concentrations. Tacrine (0–5 mg/100 ml) was used as the positive control.

MTT cell proliferation assay

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293) and human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells were all grown to confluenecy in 25 cm2 flasks. This was then trypsinized and plated into 48 well plates at specific seeding densities. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. Medium was then removed and fresh medium (MEM + Glutmax + antibiotics) was added. Extracts (50–350 µl/ml) were then added in triplicate and incubated for 4 hrs. Thereafter medium was removed and replaced by complete medium (MEM + Glutmax + antibiotics +10% Fetal bovine serum). After 48 hours cells were subjected to the MTT assay (Mosman, 1983). Data were evaluated through regression analysis using QED statistics program and from the linear equation the LC50 values representing the lethal concentration for 50% mortality was calculated.

Statistical analyses

The mean and standard error of the mean of three experiments were determined. Statistical analysis of the differences between mean values obtained for experimental groups were calculated using Microsoft excel program, 2003, Origin 6.0 for IC50 and GraphPad prism version 4. Data were subjected to one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey- Kramer multiple comparison test. In all cases, p values ≤ 0.05 were regarded as statistical significant.

Results

Percentage yield

The yield of the aqueous extract obtained from G. perpensa rhizomes was 23.50 % (w/w relative to dried material).

Milk production

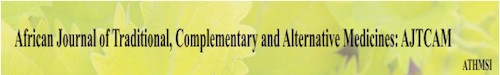

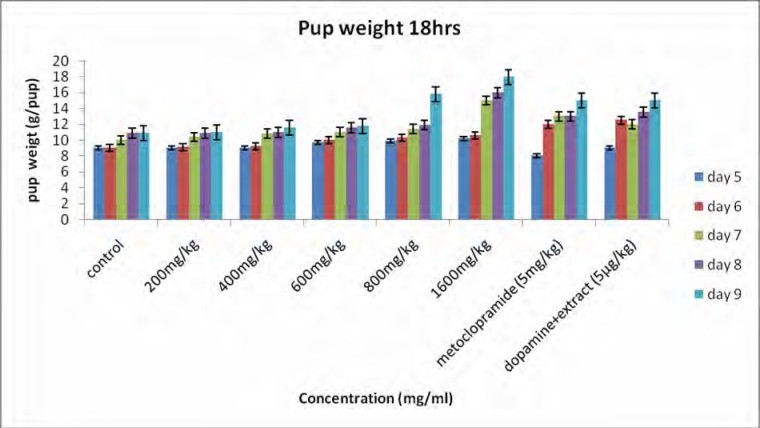

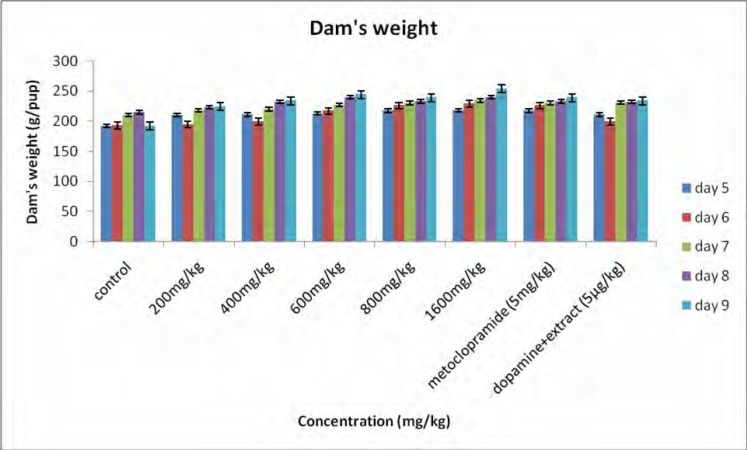

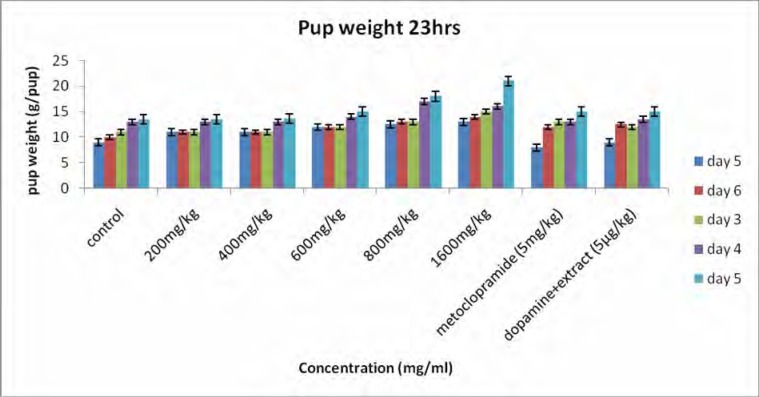

Figure 1 shows the body weights of the pups. All pups gained weight during the study period and the rate of weight gain for the treated groups was significantly higher than that for the controls. Body weight for 18 h (figure 1a) increased from 9.18±0.15 to 12.30±0.21 g/pup for the controls and for the 23 h (figure 1b) the body weight increased from 9.25±0.11 to 12.42±0.19 g/pup. For the rats receiving the extract (1600 mg/kg) the body weight for 18h increased from 10.66±0.00 to 17.90±0.27 g/pup and for 23 h the body weight increased from 11.75±0.26 to 19.99±0.24 g/pup. A significant difference was observed between treated group (1600 mg/kg) and the controls. For the dams, there was a general increase in body weight, but statistically there was no significant difference observed between the groups (figure 2). Milk production data 18 and 23 hours after gavage (Figure 3) indicated that milk yield was concentration dependent and was significantly increased in the group receiving the highest concentration (1600 mg.kg−1) of the extract.

Figure 1a.

Effect of aqueous extract of G.perpensa on pup weight after 18 h. Data obtained was represented as means ±SEM and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey- Kramer multiple comparison test.

Fifure 2.

Average weight of dam's from day 5 to 9 of the study period. Data obtained was represented as means ±SEM and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey- Kramer multiple comparison test.

Figure 3.

Effect of aqueous extract of G.perpensa on milk yield 18 h and 23 h after gavage. Data obtained was represented as means ±SEM and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey- Kramer multiple comparison test.

Figure 1b.

Effect of aqueous extract of G.perpensa on pup weight after 23 h. Data obtained was represented as means ±SEM and analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey- Kramer multiple comparison test.

Blood parameters

The results of the blood analysis of hormones are presented in Table 1a. The extract had no significant effect on the levels of prolactin, growth hormone and cortisol; progesterone levels seemed to rise with the increase in the concentration of the extracts. Progesterone levels increased by 28.4 % in the group treated with metoclopramide and by 16 % in the group with extract/dopamine compared to controls. Insulin levels decreased significantly (p< 0.05) and this decrease was concentration dependent.

Table 1a.

Serum levels of prolactin, progesterone, growth hormone, insulin and cortisol in control and extract-treated groups (mean ± SEM).

| Parameters | Groups | Control Normal saline |

Extract - treated groups | Extract 100mg.kg−1 + Dopamine 5µgkg−1 |

Metoclopramide 5mg.kg−1 |

|||

| 200mg.kg−1 | 400mg.kg−1 | 800mg.kg−1 | 1600mg.kg−1 | |||||

| Prolactin (ng/ml) |

0.6±00 | 0.6±00 NS |

0.6±00 NS |

0.6±00 NS |

0.6±00 NS |

0.6±00 NS |

0.6±00 NS |

|

| Progesterone (nmol/l) |

96.68±10.96 | 83.04±17.88 NS |

107.18±17.13 NS |

103.62±22.39 NS |

112.22±6.55 S* |

124.42±23.09 S* |

106.64±3.63 NS |

|

| Growth hormone (ng/l) |

0.05±00 | 0.05±06 NS |

0.05±02 NS |

0.05±00 NS |

0.05±00 NS |

0.05±00 NS |

0.05±00 NS |

|

| Cortisol (nmol/l) | 27±00 | 27±60 NS |

27±90 NS |

27±00 NS |

27±00 NS |

27±00 NS |

27±00 NS |

|

| Insulin (µU/ml) | 0.70±0.53 | 0.04±0.02 S* |

0.08±0.06 S* |

0.10±0.08 S* |

0.00±00 S* |

0.04±0.02 S* |

0.12±0.08 S* |

|

Not significant=NS, Significant=S* (p<0.05), Significant=S** (p<0.01), Not determined=ND.

The results of liver function tests are shown in Table 1b. No changes in ALT were found in all extract treated groups, but ALT was significantly lower in extract/dopamine group compared to control. AST was decreased in the group treated with 200 mg.kg−1 extract (p<0.05) and extract/dopamine group compared to control. Bilirubin (total and conjugated) levels were significantly decreased (p<0.001) in all experimental groups. No changes in albumin levels were recorded (Table 1b). Changes in total protein levels appeared to be concentration dependent when comparing all experimental groups. Total protein was significantly lower in extract/dopamine group.

Table 1b.

Serum levels of Alanine aminotransfrease (ALT), Aspartate amino transferase (AST), Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, total protein and albumin in control and extract-treated groups (mean ± SEM).

| Parameters | Groups | Control Normal saline |

Extract - treated groups | Extract 100mg.kg−1 + Dopamine 5µgkg−1 |

Metoclopramide 5mg.kg−1 |

|||

| 200mg.kg−1 | 400mg.kg−1 | 800mg.kg−1 | 1600mg.kg−1 | |||||

| ALT (IU/L) | 87.40±34.17 | 68.60±5.65 NS |

103±83.73 NS |

104±13 NS |

ND | 54.20±3.14 S* |

59.40±6.62 S* |

|

| AST (IU/L) | 336.60±181.63 | 125±11 S* |

188.40±40.67 NS |

193.40±24.95 NS |

ND | 88.40±7.77 S** |

129.60±30.54 S* |

|

| ALP (IU/L) | 437.00±00 | 580.8±68.32 S** |

639.00±78.49 S** |

641.4±43.63 S** |

ND | ND | 539.4±91.52 NS |

|

| Total Billirubin (umol/l) |

1.80±00 | 1.92±0.05 S** |

1.48±0.29 S** |

1.48±0.29 S** |

ND | 1.96±0.04 S** |

1.22±0.22 S** |

|

| Conjugated Billirubin (umol/l) |

1.92±0.12 | 1.80±12 S* |

1.48±0.29 S** |

1.48±0.29 S** |

ND | 1.64±0.16 S** |

1.32±0.29 S** |

|

| Total protein (g/l) |

60.60±1.69 | 57.20±1.56 S** |

55.80±1.16 S** |

65.40±1.54 S** |

66.8±0.37 S** |

55.00±1.30 S** |

60.20±1.59 NS |

|

| Albumin (g/l) | 34.60±8.39 | 37.60±1.75 NS |

30.60±1.47 NS |

39.40±0.40 NS |

ND | ND | ND | |

Not significant=NS, Significant=S* (p<0.05), Significant=S** (p<0.001), Not determined=ND

The changes in renal function metabolites are presented in Table 1c. In metoclopramide group urea showed a slight increase, whereas creatinine was decreased (p<0.001) in the groups treated with 800 mg/kg−1 extract and with metoclopramide.

Table 1c.

Serum level of urea and Creatinine in control and extract-treated groups (mean ± SEM).

| Parameters | Groups | Control Normal saline |

Extract - treated groups | Extract 100mg.kg−1 + Dopamine 5µgkg−1 |

Metoclopramide 5mg.kg−1 |

|||

| 200mg.kg−1 | 400mg.kg−1 | 800mg.kg−1 | 1600mg.kg−1 | |||||

| Urea (mmol/l) | 7.86±0.02 | 8.76±0.53 S** |

8.84±0.27 S** |

7.66±0.02 S** |

ND | ND | 8.18±0.26 S* |

|

| Creatinine (umol/l) |

68.60±0.51 | 67.2±4.75 NS |

62.4±1.08 NS |

62.6±0.24 S** |

ND | ND | 57.60±1.91 S** |

|

Not significant=NS, Significant=S* (p<0.05), Significant=S** (p<0.001), Not determined=ND.

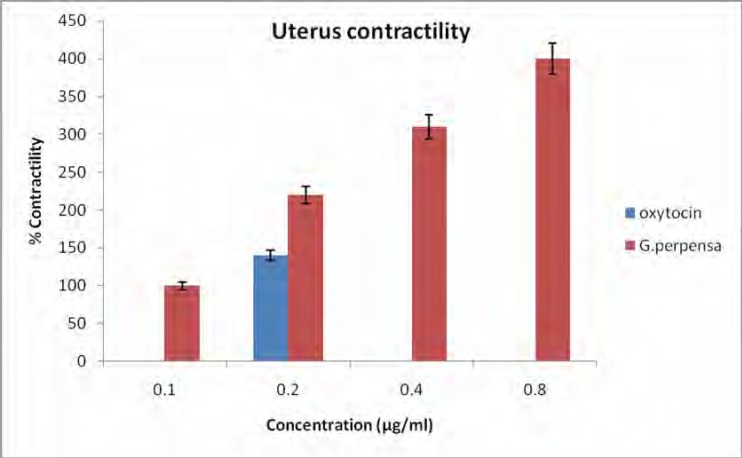

Uterus contractility

Figure 4 shows the uterus contractility caused by G.perpensa and oxytocin. The results indicate that the G. perpensa extract has constituents that significantly and dose dependently caused uterus contractility.

Figure 4.

Effect of aqueous extract of G. perpensa (GP) and Oxytocin (0.2µg/ml) on uterus contractility. Data obtained was represented as means ±SEM. Percentage (%) change in contractility are not absolute values Statistical significance was obtained using GraphPad prism version 4 and data was analyzed using one way ANOVA followed by Tukey- Kramer multiple comparison test. In all cases, values of p<0.001 was taken to imply statistical significance

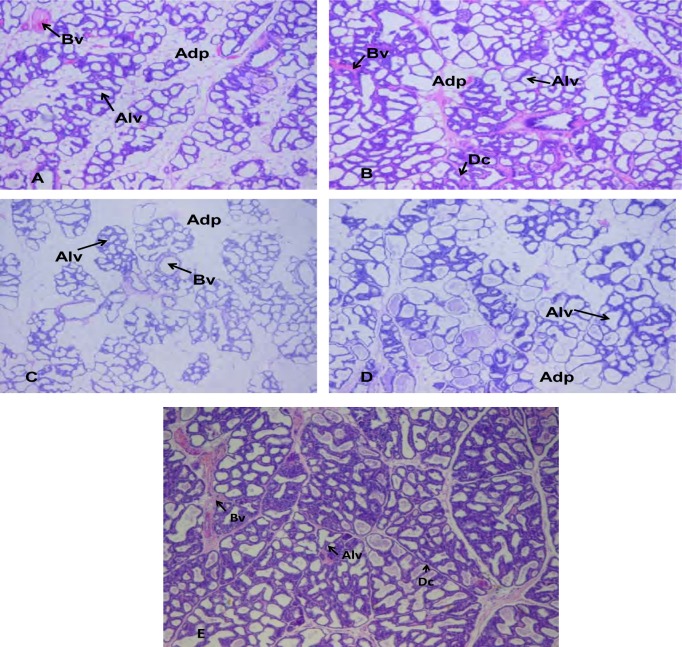

Histology of mammary tissue

The histograms of the mammary glands are shown in figure 5. The aqueous extract of G.perpensa stimulated the lobulo-alveolar system development and its activity was found to be effective at high concentration (1600 mg.kg−1). Figure 5A (normal, no treatment) shows very prominent alveoli which are lined by single layered flattened to cuboidal cells with small amounts of basophilic material (suspect secretory product) in their lumens. Cuboidal cells overall were the more prominent. The ducts are similarly lined by mostly single layered cells some also containing suspect secretory material. The acinar/adipose ratio seems approximately 80/20 to 90/10 in the different sections.

Figure 5a,b,c,d,e.

Sections of the mammary glands from lactating rats 14-20 weeks old treated with saline, extract, dopamine + extract, and metoclopramide. (A) Mammary gland from lactating rat receiving 0.9 % NaCl, showing little alveolar development and the abundance of mammary adipose cells. (B) Mammary gland from lactating rat receiving 1600 mg.kg−1 extract, showing ducts branching into ductile, with well defined alveolar development (compared to A,C and D) and fewer adipose cells. (C) Mammary gland from lactating rat receiving metoclopramide 5 mg.kg−1, showing little alveolar development and the abundance of adipose cells. (D) Mammary gland from lactating rat receiving dopamine 5 µg.kg−1+ extract 100mg.kg−1, showing little alveolar development and fewer adipose cells. (E) Mammary gland from lactating rat receiving dopamine 5 µg.kg−1, showing little alveolar development and very little adipose cells Magnification A-E x 4. Adp, adipose cells; Bv, blood vessel; Avc, alveolar cells, Dc, ductile.

Figure 5B (rats treated with extract—1600 mg/kg bw) reveals very prominent alveoli lined by single layered flattened to predominantly cuboidal cells with small amounts of eosinophilic material (suspect secretory product) in some alveoli. Secretory material is most prominent in these sections. Ducts lined by similar cells also containing suspected secretory material. The acinar/adipose ratio seems approximately 90/10 with mild focal areas of proliferation of epithelial cells forming small buds.

Figure 5C (rats treated with metoclopramide) shows very prominent alveoli lined by single layered flattened to cuboidal cells (possibly equal proportions) with small amounts of basophilic material (suspect secretory product). Ducts lined by similar cells also containing suspected secretory material. The acinar/adipose ratio seems approximately 60/40 — alveoli seem the least prominent in this group compared to the adipose tissue component.

Figure 5D (rats treated with dopamine and extract)—prominent alveoli development was observed. Cells lined by single layered flattened to cuboidal cells with small amounts of basophilic material (suspect secretory product). Cuboidal cells seem more prominent than flattened cells. Ducts similarly lined by similar cells also containing suspect secretory material. The acinar/adipose ratio seems approximately 70/30.

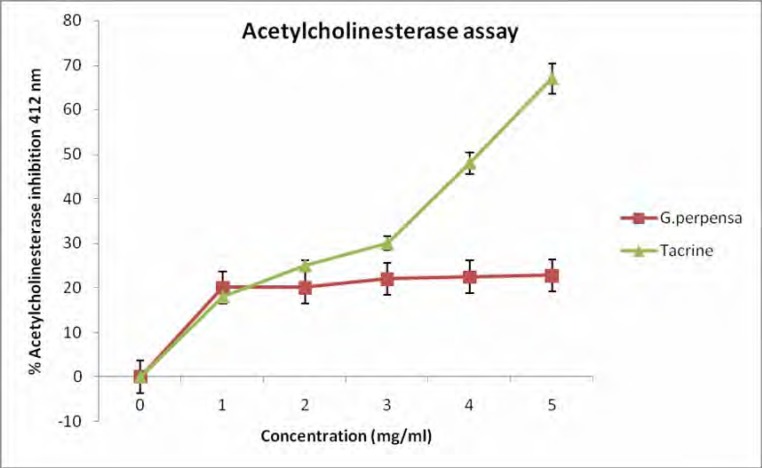

3.5. Effect of extract on acetylcholinesterase activity

The inhibition of G.perpensa extract (figure 6) on acetylcholinesterase activity showed a 23% inhibition at 5 mg/ml. This is lower than the 68% inhibition of tacrine (5 mg/ml).

Figure 6.

Effect of G. perpensa and tacrine on acetylcholinestarase, (n=3).

MTT cell proliferation

The cytotoxic activity against two human cell lines, HEK293 and HepG2 was found to be 279.43 and 222.33µg/ml, respectively.

Discussion

The floristic and ethnobotanic aspects of lactogenic plants have been studied extensively (Bailey and Day, 2004; Wynn and Fougere, 2007); however, little is known about the relationship between the stimulation of milk production, prolactin release, and mammary gland development effect of any one plant. In this study G. perpensa was investigated for its activity on milk production. Our results of milk yield (Fig 3), indicate that the extract of G. perpensa significantly (P<0.05) stimulated milk production in treated animals. Literature indicates that plants like Hibiscus sabdariffa L (Okasha et al, 2008) and Acacia nilotica ssp adansonii (Lompo-Ouedraogo, et al. 2004) exhibit their lactogenic activities through stimulation of prolactin production. Other plants like Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) and Acacia nilotica ssp adansonii increase milk production by causing development of breast tissue (Lompo-Ouedraogo et al, 2004). Even though G.perpensa extracts stimulated milk production in the presence of prolactin antagonist (dopamine), it had no observable effect on the levels of prolactin. Apparently the activity of G. perpensa on milk production is not by stimulating the lactogenic hormone (prolactin).

After parturition, prolactin induces lactation by direct stimulation of the synthesis of milk proteins in the epithelial cells and indirect stimulation of the proliferation of secretory cells. However, growth hormone (GH) is needed to support milk production when prolactin is reduced (Flint et al. 1992). In this study, the levels of GH and prolactin did not significantly change in the presence of the plant's extracts. It is observed also that G.perpensa does not significantly affect the levels of progesterone and, cortisol.

It has been reported that tissues are less sensitive to insulin stimulation during lactation, and the increase in glucose concentration could be due to an increase in milk production during lactation (Regnault et al., 2004). It is apparent from the results that insulin levels were significantly decreased (p<0.05) and the decrease was concentration dependant.

The enzymes, ALT and AST, are known as liver function index in clinical diagnosis (McLean, 1962). ALT and AST levels in this investigation have shown a tendency to be elevated with an increase in the concentration of the plant extract. Okasha et al (2008) reported such increases in the enzymes activities when Hibiscus Sabdariffa L was administered to rats. Doornenbal et al. (1998) reported the serum urea and uric acid levels to be higher in lactating cows, compared to non-lactating cows. The results reported here are similar to those in the literature. G.perpensa has antioxidant properties (Simelane et al, 2010), this is also confirmed by the stimulated level of bilirubin which is involved in the endogenous antioxidant system of the body (Elliott and Elliott, 2005).The change could be considered as an indicator of its participation. The results from the blood analysis seem to suggest that the extract of G.perpensa stimulates milk production through some means other than hormonal effect.

G. perpensa extracts stimulated uterus contraction (figure 4) and the activity was directly proportional to the concentration (p<0.001). The uterine contraction activity of Gunnera perpensa (Haloragaceae) has been reported (Khan et al, 2004). It is apparent that G. perpensa exerted its effect in milk yield through ejection by stimulating the contraction of myoepithelial cells which surround the epithelial cells of the alveoli and finer ducts.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) is known to degrade acetylcholine. AChE inhibitors play an important role in nervous system disorders owing to their potential as pharmacological and toxicological agents. Most indirect acting acetylcholine (Ach) receptor agonists work by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase. The resulting accumulation of acetylcholine causes continuous stimulation of the muscles, glands, and central nervous system (Purves et al, 2008). Even though the observed inhibition (23%) of acetylcholinesterase activity is low (figure 6), it is noteworthy that a crude extract of G. perpensa was used and thus its activity might not be as potent as that of tacrine. It is however apparent that the mechanism of action of G.perpensa to cause muscle contraction is through the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase activity.

The extent to which milk production/milk flow would have been influenced by the aqueous extracts of G.perpensa would be impossible to judge from the histological findings alone but since physiological milk yield was determined, the histology results provide the evidence that G.perpensa stimulate alveolar development. It is concluded that G. perpensa increase milk production by causing alveolar development and the contraction of myoepithelial cells leading to milk ejection.

The cytotoxicity of G.perpensa on monkey vero cells has been reported to be 250 µg/ml (Veale et al,1989). In toxicity evaluation of plant extracts by brine shrimp lethality bioassay, LC50 values lower than 1000 µg/ml are considered bioactive (Meyer et aI, 1982). It is apparent that, when dilution in the bloodstream is taken into account, G. perpensa should be regarded as non-toxic.

It is apparent that the ability of G.perpensa to stimulate milk production/secretion and the relatively weak toxic activity of the plant may contribute to its use in folk medicine. However, it is advised that G.perpensa be used medicinally with caution. In addition to these cell viability results, it has also been found that G.perpensa, significantly augments the initial response of the uterus to oxytocin, and therefore must be considered to have the potential to cause uterine hyperstimulation and its associated toxicity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Medical Research council South African (SA), National Research Fund (SA), and University of Zululand Research committee for financial support.

References

- 1.Bailey CJ, Day C. Metformin: Its botanical background. Practical. Diabetes Inter. 2004:115–117. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown TE, Fernandes PA, Grant LJ, Hutsul JA, McCoshen JA. Effect of parity on pituitary prolactin response to metoclopramide and domperidone: implications for the enhancement of lactation. J Soc GynecolInvestig. 2000;7(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(99)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buwa LV, van Staden J. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of traditional medicinal plants used against venereal diseases in South Africa. J Ethnopharmacology. 2006;103:139–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doornenbal H, Tong AK, Murray NL. Reference values of blood parameters in beef cattle of different ages and stages of lactation. Can J Vet Res. 1988;52(1):99–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drewes ES, Khan F, van Vuuren SF, Viljoen AM. Simple 1,4-benzoquinones with antibacterial activity from stems and leaves of Gunnera perpensa. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:1812–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott WH, Elliott DC. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press Inc; 2005. p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Jr, Feather-Stone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 1961;7:88–95. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(61)90145-9. 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flint DJ, Tonner E, Beattie J, Panton D. Investigation of the mechanism of action of growth hormone in stimulating lactation in the rat. Journal of Endocrinology. 1992;134:377–383. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1340377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabay MP. Galactogogues: medications that induce lactation. J Hum Lact. 2002;18:274–279. doi: 10.1177/089033440201800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan F, Peter XK, Mackenzie RM, Katsoulis L, Gehring R, Munro OQ, van Heerden FR, Drewes SE. Venusol from Gunnera perpensa: structural and activity studies. Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1117–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lompo-Ouedraogo Z, van der Heide D, van der Beek EM, Hans JM, Swarts JA, Mattheij ML. Effect of aqueous extract of Acacia nilotica ssp adansonii on milk production and prolactin release in the rat. Journal of Endocrinology. 2004;182:257–266. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mclean AEM. Hepatic failure in malnutrition. Lancet. 1962;2:1229–1295. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(62)90847-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer BN, Ferrigni NR, Putnam JE, Jacobson LB, Nichols DE, McLaughlin JL. Brine shrimp: a convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Medica. 1982;45:31–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosman T. Rapid coloricmetric assay for cellular growth and survival. Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. Journal of immunological methods. 1983;65:55–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moustafa AM, El-Sayed EM, Badary OA, Mansour AM, Hamada FMA. Effect of bromocriptine on uterine contractility in near term pregnant rats. Pharmacol Res. 1999;39(2):89–95. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1998.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndhlala AR, Stafford GI, Finnie FJ, Van Staden J. In vitro pharmacological effects of manufactured herbal concoctions used in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa. J Ethnopharmacology. 2009;122:117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nkomo M, Kambizi L. Antimicrobial activity of Gunnera perpensa and Heteromorphaarborescens var. ayssinica. Journal of Medical plant Research. 2009;3(12):1051–1055. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nkomo M, Nkeh-Chungag BN, Kambizi L, Ndebia EJ, Iputo JE. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties of Gunnera perpensa (Gunneraceae) African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2010;4(5):263–269. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v8i4.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okasha MAM, Abubakar MS, Bako IG. Study of Aqueous Hibiscus Sabdariffa Linn Seed Extract on Serum Prolactin Level of Lactating Female Albino Rats. European Journal of Scientific Research. 2008;4:575–583. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick DH, William C, LaMantia JO, McNamara AS, White LE. Neuroscience. 4th ed. Sinauer Associates; 2008. pp. 121–122. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Redgrave P, Gurney K. The short-latency dopamine signal: a role in discovering novel actions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(12):967–975. doi: 10.1038/nrn2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Regnault TR, Oddy HV, Nancarrow C, Sriskandarajah N, Scaramuzzi RJ. Glucose-stimulated insulin response in pregnant sheep following acute suppression of plasma nonesterified fatty acid concentrations. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sampson DA, Jansen GR. Measurement of milk yield in lactating rat from pup weight and weight gain. Journal of Pediatry, Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 1984;3:613–617. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198409000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simelane MBC, Lawal OA, Djarova TG, Opoku AR. In vitro antioxidant and cytotoxic activity of Gunnera perpensa L. (Gunneraceae) from South Africa. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research. 2010;4(21):2181–2188. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veale DJH, Arangies NS, Oliver DW, Furman KI. Preliminary isolated organ studies using an aqueous extract of Clivia miniata leaves. J Ethnopharmacol. 1989;27:341–346. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vonderhaar BK. Prolactin: Transport, function, and receptors in mammary gland development and differentiation. In: Neville MC, Daniel CW, editors. The mammary gland. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. pp. 383–438. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watson CJ, Khaled WT. Mammary development in the embryo and adult: a journey of morphogenesis and commitment. Development. 2008;135:995–1003. doi: 10.1242/dev.005439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.William HB, Ruth AL. Comparison of the Cariogenicity of Cola,Honey, Cattle Milk, Human Milk, and Sucrose. Pediatrics. 2005;116:921–926. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wynn SG, Fougere BJ. Veterinary Herbal Medicine. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]