Abstract

Study Objectives:

Growing evidence indicates sleep is a major public health issue. Race/ethnicity and socioeconomics may contribute to sleep problems. This study assessed whether sleep symptoms were more prevalent among minorities and/or the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Design:

Cross-sectional.

Setting:

Epidemiologic survey.

Patients or Participants:

2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (N = 4,081).

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Results:

Sociodemographics included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and immigration. Socioeconomics included poverty, education, private insurance, and food insecurity. Sleep symptoms assessed were sleep latency > 30 min, difficulty falling asleep, sleep maintenance difficulties, early morning awakenings, non-restorative sleep, daytime sleepiness, snorting/gasping, and snoring. Decreased reported problems for most symptoms were found among minorities, immigrants, and lower education levels. In general, in fully adjusted models, long sleep latency was associated with female gender, being black/African American, lower education attainment, no private insurance, and food insecurity. Difficulty falling asleep, sleep maintenance difficulties, early morning awakenings, and non-restorative sleep were also associated with female gender and food insecurity. Daytime sleepiness was seen in female and divorced respondents. Snorting/gasping was more prevalent among male, other-Hispanic/Latino, and 9th- to 11th-grade-level respondents. Snoring was prevalent among male, other-Hispanic/Latino, less-educated, and food-insecure respondents.

Conclusions:

Sleep symptoms were associated with multiple sociodemographic and economic factors, though these relationships differed by predictor and sleep outcome. Also, reports depended on question wording.

Citation:

Grandner MA; Petrov MER; Rattanaumpawan P; Jackson N; Platt A; Patel NP. Sleep symptoms, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. J Clin Sleep Med 2013;9(9):897-905.

Keywords: Insomnia, sleep disorders, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, health disparities

Sleep deprivation and common sleep disorders (e.g., insomnia and sleep apnea) represent a major unmet public health problem.1 Suboptimal sleep attainment is associated with negative effects in brain function2 and health status.3 Sleep apnea and insomnia also have been associated with negative health outcomes in multiple studies.4,5

Insomnia, characterized by difficulty falling asleep and/or maintaining sleep, is an important public health issue.6–11 Obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by loud snoring, pauses in breathing during sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness, is also relatively prevalent.12 Many studies have demonstrated that sleep apnea is associated with significant medical morbidity—particularly cardiometabolic disease.13

Sleep symptoms, even if subclinical, are also an important public health issue. General sleep disturbance (difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or sleeping too much) is prevalent14 and elevated in individuals who are obese or have a history of obesity, heart disease, diabetes, heart attack, and/ or stroke.15 Individuals who report poor health or complain of depressive symptoms are at greater risk of experiencing poor sleep.16

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Social and environmental factors associated with short sleep duration are not well characterized at the population level. The relationship between sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors may be complex in relation to sleep duration.

Study Impact: These findings help identify groups at particular risk of potentially unhealthy sleep durations. This also aids in the identification of factors that will be relevant in the development and implementation of community and population level interventions.

These findings are particularly relevant for individuals from certain sociodemographic and socioeconomic groups, as differences in sleep and sleep disparities (ameliorable differences) may place these groups at increased risk of poor health outcomes. Several studies have documented sleep impairments across racial/ethnic groups,14,17–20 but findings are generally equivocal or difficult to interpret. Overall, African Americans may be less likely to report sleep problems,21 but may be at greater risk for both short and long sleep duration.19,22 Very little data about Hispanic/Latino groups exists, though these data also suggest the presence of differences.23 Also, few studies have explored immigration status relating to sleep, but there appears to be a generally protective effect of being an immigrant.24

Regarding socioeconomic position, several studies have documented relationships between sleep disturbances and poverty14,25–28 and educational attainment.14,29,30 However, these findings are likely complicated by interactions/confounding with other demographic and economic factors.14,31 Other socioeconomic indicators have rarely been explored relative to sleep.

There are several limitations with the existing literature. First, few existing studies have been able to examine nationally representative data. Second, in the instances where highly generalizable samples were obtained, sleep was often assessed along a single dimension or item. Third, few existing studies have simultaneously assessed numerous dimensions of demographics and socioeconomics to explore unique effects. Non-simultaneous assessment limits interpretation, as many sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors are inter-correlated.

Accordingly, the present study reflects an analysis of a nationally representative dataset (2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) that assessed diverse self-reported sleep symptoms (i.e., difficulty falling asleep, difficulty with sleep maintenance, early morning awakenings, non-restorative sleep, daytime sleepiness, snoring, and snorting/gasping during sleep). This dataset captured several sociodemographic dimensions, including race/ethnicity and immigration status. In addition, this dataset captured socioeconomics multidimensionally, with assessments of poverty, education level, access to private health insurance, and food insecurity (i.e., a state whereby an individual encounters obstacles when attempting to provide adequate food for themselves and their family32). Since these factors can be highly inter-correlated, the present analysis aims to explore unique effects of each of these factors, adjusting for all others.

We believe this analysis is unique because it determines whether sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors are associated with increased prevalence of sleep symptoms, and includes novel variables such as immigration status, access to private health insurance, and food insecurity. We hypothesize that meaningful relationships exist between sleep symptoms and all assessed sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors. Specifically, we hypothesize that increased sleep symptoms will be observed among minorities, native-born, and socioeconomically disadvantaged participants (poor, those who experience food insecurity, those with less education, and those without private health insurance). It should be noted that this hypothesis reflects a paradox, that previous literature suggests poor sleep among blacks/African Americans and (to a lesser extent) Hispanics/Latinos, but improved sleep and health among immigrants, who are more likely to be minorities. The present analyses will examine the unique effects of both of these dimensions. Further, we hypothesize that many of these effects will be independent of all other sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors, as well as overall mental and physical health.

METHODS

NHANES Sample

The subjects used in this study were participants in the 2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a national survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, reporting the health and nutritional characteristics of children and adults. Participants (N = 9,762) were administered questionnaires concerning their demographic, socioeconomic, and nutritional status during in-person interviews conducted in the home. The NHANES survey oversampled African Americans, Hispanics, and adults over 60 years.33

Sampling in this survey was performed to ensure generalizability to the entire population across all ages. Because of the complexity of the survey design coupled with variable probabilities of selection, the data used in the following analyses were also weighted to control for representativeness according to procedures outlined in the current NHANES Analytic and Reporting Guidelines.34 For the present study, completed data from the sleep disorders, sociodemographics, socioeconomics, and health covariates modules were used in the analyses. Although these modules were conducted in direct interviews with survey participants 16 years of age or older, study analyses only included adults aged 18 years or older with complete data on all independent and dependent variables (n = 5,587). All participants provided written informed consent and were treated in keeping with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sleep Symptoms

Sleep disorders are highly underdiagnosed1; therefore, the assessment of sleep symptoms of common disorders has practical value. Commonly accepted diagnostic criteria for insomnia include difficulty falling asleep, difficulty with sleep maintenance, and/or early morning awakenings (awakening before the intended time with difficulty resuming sleep), in the context of daytime impairment and sufficient time available for sleep.35 Self-reported symptoms commonly experienced in the context of sleep apnea include non-restorative sleep, daytime sleepiness, snoring, and snorting/gasping during sleep,12 though diagnosis of sleep apnea requires objective assessment. Although the items included in the NHANES survey have not been validated for screening insomnia or sleep apnea, many of these symptoms were assessed. Accordingly, the sleep symptoms included in the present analysis were: (1) sleep latency > 30 min, (2) difficulty falling asleep, (3) difficulty with sleep maintenance, (4) early morning awakenings, (5) daytime sleepiness, (6) non-restorative sleep, (7) snorting/gasping during sleep, and (8) snoring.

Sleep latency was assessed continuously using the item, “How long does it usually take you to fall asleep at bedtime?” Responses were dichotomized to < 30 min or > 30 min, consistent with insomnia diagnostic criteria.35 Difficulty falling asleep was assessed with the item, “In the past month, how often did you have trouble falling asleep?” Difficulty with sleep maintenance was assessed with the item, “In the past month, how often did you wake up during the night and had trouble getting back to sleep?” Early morning awakenings were assessed with the item, “In the past month, how often did you wake up too early in the morning and were unable to sleep?” Non-restorative sleep was assessed with the item, “In the past month, how often did you feel unrested during the day, no matter how many hours of sleep you have had?” Responses for these variables were either “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” “Often,” and “Almost Always.” Snorting/gasping during sleep was assessed with the item, “In the past 12 months, how often did you snort, gasp, or stop breathing while you were asleep?” Snoring was assessed with the item, “In the past 12 months, how often did you snore while you were sleeping?” Responses for these variables were “Never,” “Rarely,” “Sometimes,” or “Frequently.”

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic variables included in the analysis included (1) race/ethnicity, (2) immigration status, (3) age, (4) sex, and (5) marital status. Categories for race/ethnicity included non-Hispanic white, black/African American, Mexican-American, Other Hispanic/Latino, and Asian/other. Marital status was classified as married, living with partner, never married, divorced, separated, and widowed. Immigration status was classified as born in the US, born in Mexico, or born in another country. Although immigration status has not been evaluated relative to sleep in this way, previous studies have found that sleep disorder risk factors are differentially distributed across immigrants and non-immigrants.24,36,37 Mexico-born individuals were assessed separately from those born in other countries because Mexico-born individuals make up the largest group of immigrants38 and there are different levels of health risks between these groups.39,40

Socioeconomic Position

Socioeconomic variables included (1) poverty, (2) education, (3) access to private health insurance, and (4) food security. Poverty was assessed as total household income above or below $20,000. This dichotomization was based on self-reported income, which included several categories above and below $20,000. This allowed us to retain the maximum number of respondents. Education level was categorized as < 9th grade, 9th to 11th grade, high school graduate (including GED), some college (including Associates degree), and college graduate. Household food security was categorized as full food security, marginal food security, low food security, and very low food security. This determination was based on standardized NHANES procedures based on responses to a combination of 18 items that assessed running out of food, inability to afford food, skipping meals, inability to provide adequate food for children, and other, similar items.41,42

Health Covariates

Physical health was assessed using the question, “Thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?” Similarly, mental health was assessed with, “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” These were recorded as continuous variables (range 0-30).

Statistical Analyses

Complete case analysis and a frequency weighting scheme were used to analyze the data. Two-year full sample weight was used to adjust for unequal probability of being selected among non-coverage or non-response populations. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages, while continuous variables were expressed in terms of mean (± SD). To assess unadjusted associations between each sleep outcome and sociodemographic or socioeconomic variable, Rao-Scott χ2 was used. We then performed unadjusted and adjusted ordinal logistic regression analyses, with sleep symptoms as the primary outcomes and sociodemographic/socioeconomic variables(s) as predictor(s), using Wald tests. A total of 3 separate regression models were evaluated. Model 1 evaluated bivariate relationships (unadjusted). Model 2 evaluated relationships after adjustment for all other sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables (adjusted). Model 3 evaluated relationships after adjustment for all Model 2 variables, and physical and mental health measures. A 2-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical calculations were performed by using STATA/SE version 11.1 (STATA Corp, College Station TX).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

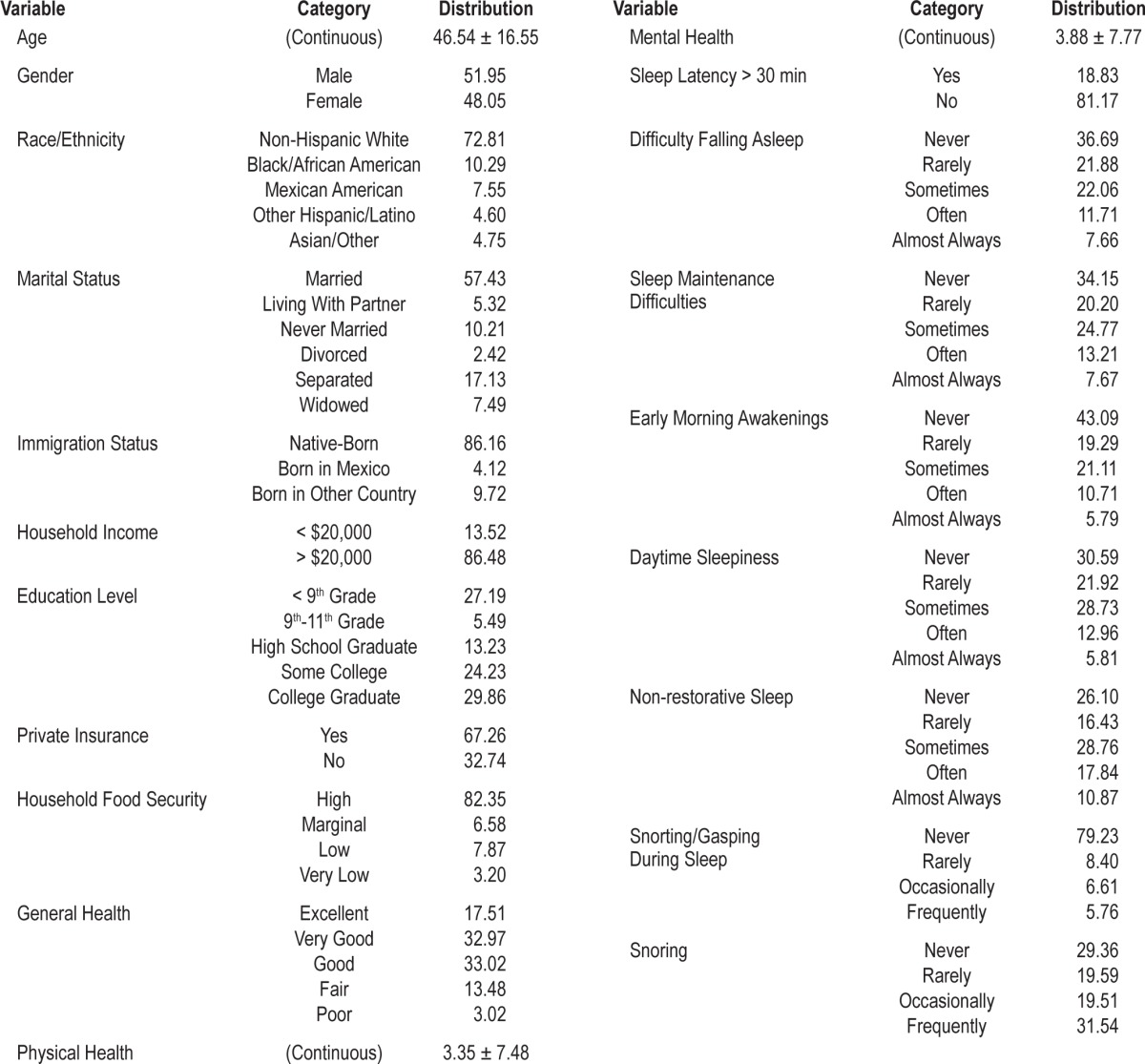

Characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 1, based on the NHANES sampling weights. This was, in general, a healthy, nonclinical sample. Due to non-response on some items, actual N values per analysis varied. These ranged from N = 3,554 to N = 4,081. See data tables for N per analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample (weighted), expressed as percent (%) for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD) for continuous variables

Using χ2, distributions of sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables by each sleep variable were evaluated. Significant differences were found for most tests. For sleep latency > 30 min, difficulty falling asleep, sleep maintenance difficulties, early morning awakenings, and non-restorative sleep, significant differences were seen for all variables. For snorting and gasping, significant differences were seen for general health, marital status, food security, education, and immigrant status. For snoring, differences were seen for marital status and education.

Unadjusted Regression Analyses

Unadjusted regression analyses are reported in Table S1 for sleep continuity-related variables (sleep latency > 30 min, difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and early morning awakenings) and Table S2 for sleep quality-related variables (daytime sleepiness, non-restorative sleep, snorting/ gasping, and snoring). In unadjusted analyses, sleep latency > 30 min was more frequently reported among black/African American and other Hispanic/Latino respondents, versus non-Hispanic white. However, black/African American, other Hispanic/Latino, and Mexican American respondents reported less difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, nonrestorative sleep, and daytime sleepiness. Also, Asians/other reported less difficulty maintaining sleep, and Mexican Americans reported fewer early morning awakenings. Those born in Mexico or another country were less likely to report difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, daytime sleepiness, and non-restorative sleep; those born in another country were less likely to report snorting/gasping. Low income was associated with increased reports of all sleep continuity symptoms. Lower education was generally associated with more symptoms, though the education categories fluctuated. Of note, the lowest education category (< 9th grade) frequently reported fewer problems than those with college education. Household food security, especially in the very low category, was consistently related to sleep continuity and sleep quality symptoms.

Adjusted Analyses

Adjusted regression analyses examined unique effects of variables in the context of other demographic and socioeconomic factors. Since many of these factors are correlated with each other, these analyses report the variance contributed by each factor, after accounting for any variance accounted for by other factors. These results are reported in Table S3 for sleep continuity variables and Table S4 for sleep quality variables. In these analyses black/African American respondents were still more likely to report sleep duration > 30 min but less likely to report difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, non-restorative sleep and daytime sleepiness. Similarly, Mexican Americans (and Mexico-born immigrants) were less likely to report difficulty falling asleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, early morning awakenings, nonrestorative sleep, and daytime sleepiness, and other Hispanic/ Latino respondents were less likely to endorse difficulty falling asleep, non-restorative sleep, daytime sleepiness, snorting/ gasping and snoring. Many effects in the socioeconomic domain were attenuated in adjusted analyses, but some unique effects were noted. In particular, lower socioeconomic status was generally associated with increased likelihood of sleep latency > 30 min and, to a lesser degree, snorting/gasping. Low and very low food security were also still consistently associated with sleep symptoms.

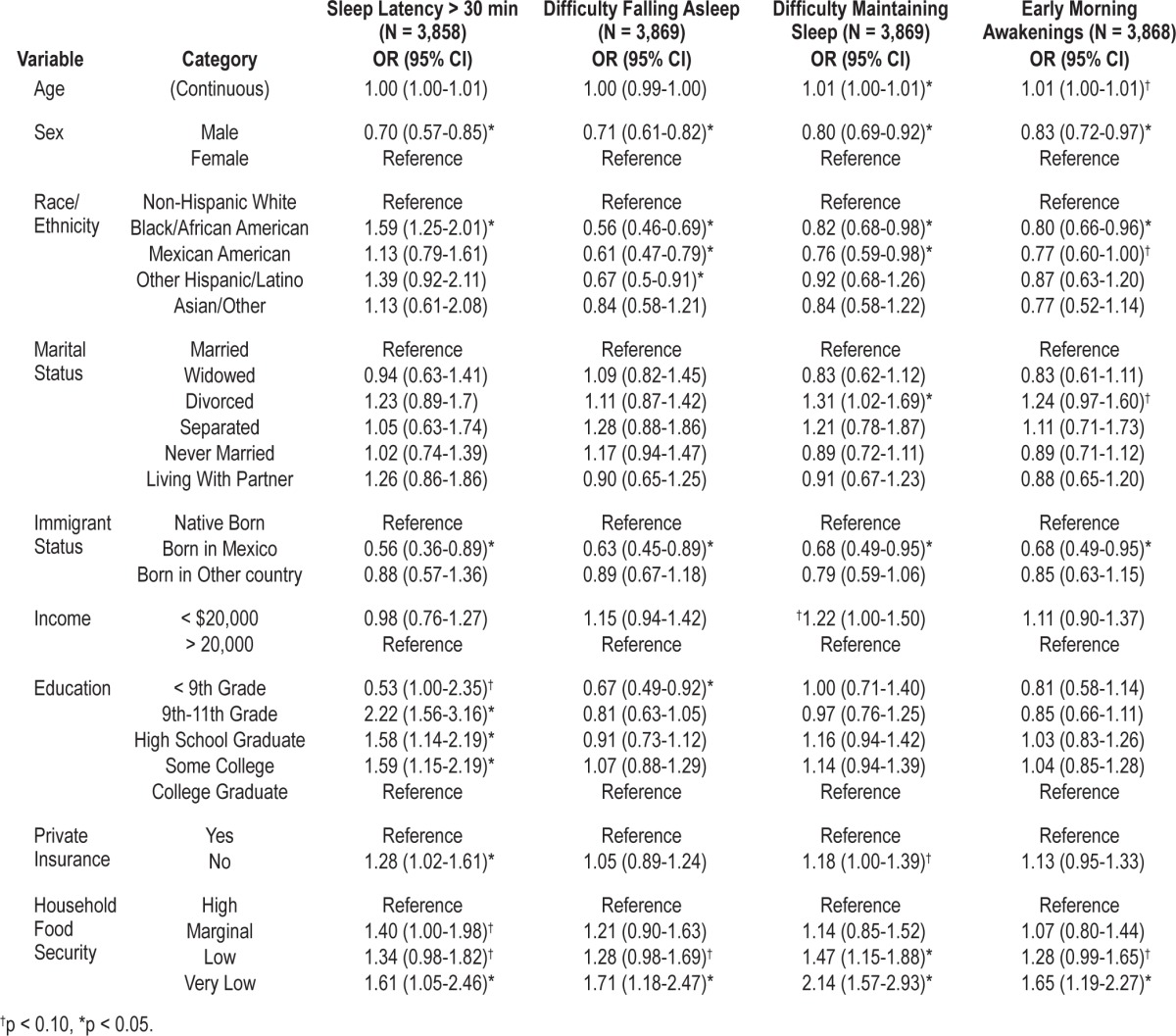

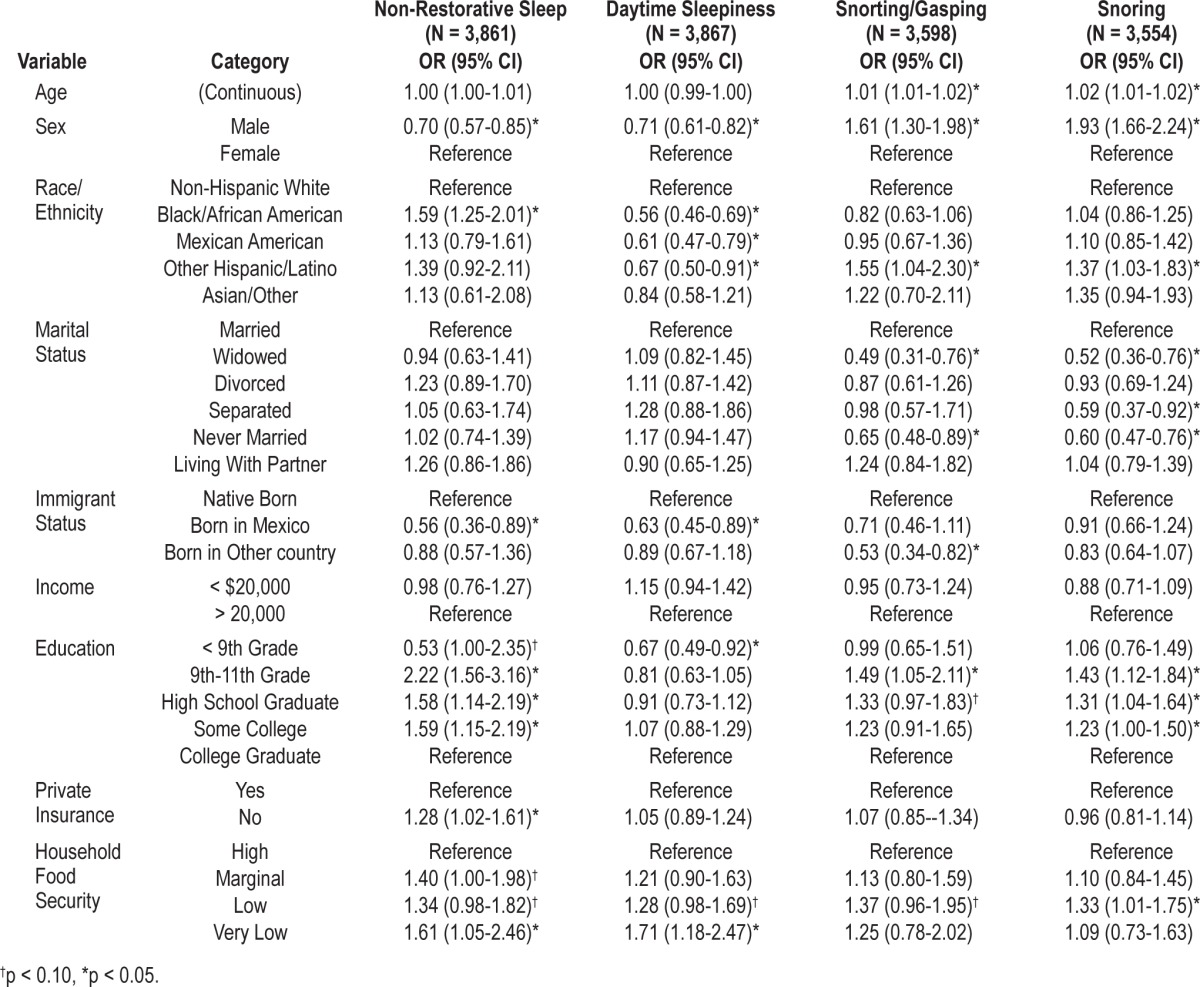

Fully Adjusted Analyses

These analyses reflect unique effects of factors, similarly to the adjusted analyses, except that any variance accounted for by overall health is also excluded. These results are reported in Table 2 for sleep continuity variables and Table 3 for sleep quality variables. As before, black/African American respondents and those with lower education were more likely to report sleep latency > 30 min. In the case of other sleep symptoms, lower levels were generally reported by minorities and immigrants. As before, very low food security was still associated with all sleep continuity variables, as well as non-restorative sleep.

Table 2.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep continuity disturbance (fully adjusted)

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep quality and daytime sleepiness (fully adjusted)

DISCUSSION

The present study utilized data from the 2007-2008 NHANES to assess whether sleep symptoms were differentially endorsed relative to sociodemographic factors (including age, sex, race/ethnicity, immigration status, and marital status) and/or socioeconomic factors (including poverty, employment, education, access to health insurance, and food insecurity). In addition we explored whether these relationships were maintained after adjustment for (1) other sociodemographic/socioeconomic factors, and (2) for overall health. Overall, all sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors were variously associated with sleep symptoms, and many of these associations were maintained in adjusted analyses.

The present study found a number of patterns of sleep symptoms relative to race/ethnicity in the population, though the majority of these were explained by other sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and health variables. We found that black/African American respondents may be at increased risk for insomnia but may be more likely to deny experiencing symptoms.43

Sleep symptoms were evaluated separately for Mexican Americans and those of other Hispanic/Latino backgrounds. For several symptoms, the pattern was similar for both groups, with both being less likely than non-Hispanic white respondents to report difficulty falling asleep, daytime sleepiness, and non-restorative sleep. Although both groups reported fewer sleep maintenance difficulties than non-Hispanic whites in unadjusted analyses, only the relationship for Mexican Americans was maintained in fully adjusted analyses. Other symptoms showed different patterns as well. For example, other Hispanic/Latino respondents were more likely to endorse snorting/gasping and snoring, as compared to non-Hispanic Whites. These findings are difficult to interpret, as there is little research on sleep symptoms among Hispanic/Latino Americans. Some studies have shown that Hispanic/Latino individuals may be high risk for sleep apnea44 and less likely to articulate symptoms of insomnia and/or sleep apnea because of varying levels of acculturation.45 These findings also support previous research that reports the relationship of sleep and obesity is differentially distributed among major subgroups of Hispanics/Latinos,46 suggesting that the heterogeneity of this group needs to be taken into account.

The present analyses showed little to no difference between sleep symptoms among Asians/others and non-Hispanic Whites. The only exception is a lower rate of non-restorative sleep among Asians/others. This exception is consonant with previous findings, which have shown lower rates of sleep disturbances among Asians.14

Few studies have investigated sleep relative to immigration status. Our findings indicate that those born in Mexico are less likely than US-born respondents to report many sleep symptoms. Being born in a different country was also protective, with those individuals being less likely to report sleep maintenance difficulties and snorting/gasping during sleep. These findings are consonant with previous evidence, denoting that immigrants report fewer sleep symptoms.24,39 Immigrants may be more likely to work in professions that require manual labor or long hours, so they may be less likely to have difficulty sleeping. Other characteristics of immigrants that may contribute to decreased reports of sleep disordered symptoms include a healthier diet47 or simply lack of knowledge about sleep symptoms.45 It should be noted that many areas of negative impact due to immigration lie in the socioeconomic domain, which is partially adjusted for in these analyses. It should be noted that Mexico-born and other immigrants were analyzed separately for several reasons. First, they were measured separately and this analytic approach captures the variation inherent in the measurement strategy. Second, Mexico-born immigrants are the largest immigrant group. Since they are presumably more homogeneous than the “other” category, separating them out could (1) provide information regarding whether they are more like immigrants or more like US Latinos, and (2) provide information as to whether the “other” group is too heterogeneous to detect any effects (or demonstrate inflated variance in estimates). Also, if we combined these groups, the Mexico-born group would drown out effects of the “other” immigrant group, due to its size relative to the other group.

Education level is frequently used as a proxy for socioeconomic status in the sleep literature,30,48 because it grossly approximates it. Most studies, though, are not powered to assess many levels of educational attainment. The present study is unique, in that it separates those who finished school before the 9th grade from others who are not high school graduates. This allows for a level of abstraction not typically available. Our results suggest this was a useful differentiation. For example, relative to college graduates, individuals with lower levels of educational attainment were more likely to report long sleep latency and snoring, except the < 9th grade group. In the fully adjusted model, reports of difficulty falling asleep, sleep maintenance difficulties, non-restorative sleep, and daytime sleepiness were lower in this group than the college-educated group. This suggests that when other relevant factors are controlled, those with the lowest educational attainment actually reported fewer symptoms than those with the highest. Our results are in contrast to several previously published studies of sleep,14,30,48 which reported lower socioeconomic status including education level was associated with worse sleep. It is important to note that this study reflects one of the first to examine sleep complaints among those with the lowest educational attainment (< 9th grade)—other studies usually do not examine those with less than a high school diploma in separate groups due to small sample size. This study afforded this unique opportunity. That this group seemed to be somewhat protected may be due to confounding factors unique to this group—they are more likely to be immigrants, for example. A better characterization of the factors associated with fewer sleep complaints among this education group is needed.

Lower income is associated with poor sleep.14,26 In particular, those in poverty are more likely to experience sleep problems than those not in poverty.26 Our study generally replicated this pattern in the unadjusted analyses, such that those with household income less than $20,000 were more likely to report multiple sleep disordered symptoms. Presumably, higher income usually provides benefits of better health care, more stable home environment, and other benefits. When many of these benefits are accounted for (as in our fully adjusted model), the increased risks associated with poverty are no longer found. This suggests that it is not income that leads to changes in sleep—rather, it is what the income buys. Future studies that examine sleep in the context of poverty (and/or wealth) should aim to sufficiently capture potential confounders in analyses.

Access to private health insurance is another indicator of socioeconomic status. In the present study, those without private healthcare access were more likely to report long sleep latency, early morning awakenings, and snorting/gasping during sleep. However, as with the measure of poverty, when other variables were taken into account, only the relationship with long sleep latency remained. One previous study has examined access to private health insurance in the context of sleep and health,3 though it was included in that study as a covariate. Access to healthcare in general (assessed as time since last health-care visit) has been examined previously. Two studies using the data from the 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System found that among women, those with more recent healthcare visits reported less sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue,16 and that healthcare visits plays a significant role in geographic distributions of sleep disturbance.49 Future studies should assess sleep in the context of healthcare access.

Food insecurity has not previously been explored relative to sleep symptoms. In the present analysis, lower food security was associated with increased prevalence of all measured sleep symptoms. Nearly all of these relationships were maintained in fully adjusted analyses. This suggests that food insecurity is a unique stressor, with impact on sleep over and above the effects of any measured sociodemographic or socioeconomic variable, or even the poorer physical and/or mental health that might be associated with the inability to provide proper food. In many cases, the effect of food insecurity was the largest in magnitude in predicting sleep symptoms. Therefore, food insecurity is an important, novel socioeconomic indicator relative to sleep.

Implications

The present study represents the first comprehensive examination of “sleep disparities” relative to demographic and socioeconomic factors to leverage a nationally representative dataset. These analyses document how sleep symptoms are differentially experienced according to race/ethnicity, immigrant status, marital status, age and sex, education, poverty, access to private insurance, and food insecurity. Further, these analyses document, for the first time, which of these relationships represent unique contributions, adjusted for a number of relevant covariates.

The term “disparity” refers to a state of inequality borne of unfairness.50 For example, when two groups differ, it is an inequality; when two groups differ because of unfairness (e.g., unequal treatment or unequal access to resources), then that is a disparity. Addressing disparities in health, particularly disparities associated with minority race/ethnicity and lower socioeconomic position, is a major goal of a number of agencies, including the National Institutes of Health, which recently founded a new Institute to address this issue.51 Many previous studies have identified disparities in health, but very few have addressed the issue of disparities in sleep, even though sleep is an important determinant in overall health. This study represents an important step in characterizing disparities. Future studies will be needed to provide a more complete picture of how sleep health is differentially experienced among vulnerable groups. Also, once these inequalities (or disparities) are identified, interventions will be needed to ameliorate them. An additional consideration is the conceptualization of sleep health as a potentially modifiable factor that partially mediates the relationship between membership in a vulnerable group (e.g., minority or low socioeconomic position) and adverse health outcomes, which will need to be explored in future studies.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, the cross-sectional nature of the analysis precludes any interpretations regarding causality. It is likely that suboptimal living conditions lead to suboptimal sleep experiences, and conversely, poor sleep predisposes individuals to worse health, well-being, and functioning, which could negatively influence the environment. It is also possible that interactions among predictors are evident, such that the relationship between sleep and socioeconomics depends on race/ethnicity. Interactions have been reported previously, though only with a measure of general sleep disturbance and not specific symptoms. Future studies will be needed to discern whether and how the relationship between sleep and socioeconomics depends on race/ethnicity and other demographic factors.

Second, the retrospective, self-report measures of sleep characteristics are not validated measures of sleep and sleep disturbance. Also, the large-scale nature of national datasets often precludes more in-depth assessments. That said, these results should be interpreted in this context. Replication using established sleep measures and/or sleep disorder screening questionnaires is needed. Currently, no nationally representative data exist using validated sleep measures. Future incorporation of sleep measures in national surveys should consider using validated measures, or validating the current items.

Third, although a nationally representative sample provides important benefits of generalizability and reliability, such a sample also presents the problem of aggregation of a very heterogeneous sample. Several problems could emerge from this. For instance, minorities from certain parts of the country may experience more racism than minorities in other areas (and perceived racism is independently associated with poor sleep).52 Also, issues of educational achievement, poverty, access to healthcare, and other factors may have different consequences by region. Future studies should include more detailed geographic considerations, to determine if these effects appreciably affect results.

CONCLUSIONS

Associations between sleep symptoms and race/ethnicity and socioeconomic position in the national population are documented. Sleep symptoms are disproportionately experienced by individuals based on their race/ethnicity, immigration status, poverty status, education level, access to healthcare, food insecurity, and other factors. It is unclear how disparities in sleep contribute to the well-described social gradient of health.53 Longitudinal studies incorporating sleep parameters alongside other important health parameters would provide a platform to assess how sleep factors may influence disparities in health. Future research should more carefully describe interactions among sociodemographic and socioeconomic variables and utilize these data to better design and implement sleep interventions in targeted populations.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by 12SDG9180007 (AHA), K23HL110216 (NHLBI), R21ES022931 (NIEHS), and the University of Pennsylvania CTSA (UL1RR024134). Also, we wish to thank the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for collecting these data and making them available, as well as the NHANES participants.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep continuity disturbance (unadjusted)

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep quality and daytime sleepiness (unadjusted)

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep continuity disturbance (adjusted)

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep quality and daytime sleepiness (adjusted)

REFERENCES

- 1.Colten HR, Altevogt BM Institute of Medicine Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. Sleep disorders and sleep deprivation: an unmet public health problem. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks S, Dinges DF. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:519–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buxton OM, Marcelli E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1027–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O'Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:47–112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson LM, Nutt DJ, Wilson SJ. Sleep and its disorders in translational medicine. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:1226–34. doi: 10.1177/0269881111400643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyle SD, Morgan K, Espie CA. Insomnia and health-related quality of life. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Espie C, et al. Chronic insomnia: clinical and research challenges--an agenda. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44:1–14. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott GW, Scott HM, O'Keeffe KM, Gander PH. Insomnia - treatment pathways, costs and quality of life. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2011;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-7547-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leger D, Bayon V. Societal costs of insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wade AG. The societal costs of insomnia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;7:1–18. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S15123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skaer TL, Sclar DA. Economic implications of sleep disorders. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:1015–23. doi: 10.2165/11537390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lurie A. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and treatment options. Adv Cardiol. 2011;46:1–42. doi: 10.1159/000327660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monahan K, Redline S. Role of obstructive sleep apnea in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:541–7. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32834b806a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Gehrman PR, et al. Who gets the best sleep? Ethnic and socioeconomic factors related to sleep disturbance. Sleep Med. 2010;11:470–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grandner MA, Jackson NJ, Pak VM, Gehrman PR. Sleep disturbance is associated with cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. J Sleep Res. 2012;21:427–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grandner MA, Martin JL, Patel NP, et al. Age and sleep disturbances among american men and women: data from the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Sleep. 2012;35:395–406. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mezick EJ, Hall M, Matthews KA. Sleep duration and ambulatory blood pressure in black and white adolescents. Hypertension. 2012;59:747–52. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.184770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zizi F, Pandey A, Murrray-Bachmann R, et al. Race/ethnicity, sleep duration, and diabetes mellitus: analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Med. 2012;125:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hale L, Do DP. Racial differences in self-reports of sleep duration in a population-based study. Sleep. 2007;30:1096–103. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hale L, Do DP. Sleep and the inner city: How race and neighborhood context relate to sleep duration. Population Association of America Annual Meeting Program.2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jean-Louis G, Magai C, Casimir GJ, et al. Insomnia symptoms in a multiethnic sample of American women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:15–25. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nunes J, Jean-Louis G, Zizi F, et al. Sleep duration among black and white Americans: results of the National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:317–22. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loredo JS, Soler X, Bardwell W, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE, Palinkas LA. Sleep health in U.S. Hispanic population. Sleep. 2010;33:962–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.7.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jean-Louis G, Magai CM, Cohen CI, et al. Ethnic differences in self-reported sleep problems in older adults. Sleep. 2001;24:926–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kachikis AB, Breitkopf CR. Predictors of sleep characteristics among women in Southeast Texas. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22:e99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel NP, Grandner MA, Xie D, Branas CC, Gooneratne N. “Sleep disparity” in the population: poor sleep quality is strongly associated with poverty and ethnicity. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:475. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the United States: a cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1052–63. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stamatakis KA, Kaplan GA, Roberts RE. Short sleep duration across income, education, and race/ethnic groups: population prevalence and growing disparities during 34 years of follow-up. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:948–55. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HJ, Ruger JP. Socioeconomic disparities in behavioral risk factors and health outcomes by gender in the Republic of Korea. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gellis LA, Lichstein KL, Scarinci IC, et al. Socioeconomic status and insomnia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:111–8. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grandner MA, Lang RA, Jackson NJ, Patel NP, Murray-Bachmann R, Jean-Louis G. Biopsychosocial predictors of insufficient rest or sleep in the American population. Sleep. 2011;34:A260. Abstract Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Agency for International Development. Washington, DC: USAID; 1992. Policity Determinition: Definition of Food Security. [Google Scholar]

- 33.NCfHS, editor. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007/2008. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. Analytic and reporting guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edinger JD, Wyatt JK, Stepanski EJ, et al. Testing the reliability and validity of DSM-IV-TR and ICSD-2 insomnia diagnoses: results of a multitrait-multimethod analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:992–1002. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casimir GJ, Jean-Louis G, Butler S, Zizi F, Nunes J, Brady L. Perceived insomnia, anxiety, and depression among older Russian immigrants. Psychol Rep. 2010;106:589–97. doi: 10.2466/pr0.106.2.589-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirooka N, Takedai T, D'Amico F. Lifestyle characteristics assessment of Japanese in Pittsburgh, USA. J Community Health. 2012;37:480–6. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shrestha LB, Heisler EJ. The changing demographic profile of the United States. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seicean S, Neuhauser D, Strohl K, Redline S. An exploration of differences in sleep characteristics between Mexico-born US immigrants and other Americans to address the Hispanic paradox. Sleep. 2011;34:1021–31. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hale L, Rivero-Fuentes E. Negative acculturation in sleep duration among Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13:402–7. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Algvere PV, Marshall J, Seregard S. Age-related maculopathy and the impact of blue light hazard. Acta Ophthal Scand. 2006;84:4–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey MEC In-Person Dietary Interviewers Procedure Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grandner MA, Patel NP, Jean-Louis G, et al. Sleep-related behaviors and beliefs associated with race/ethnicity in women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2013;105:4–15. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30080-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Surani S, Aguillar R, Komari V, Surani A, Subramanian S. Influence of Hispanic ethnicity in prevalence of diabetes mellitus in sleep apnea and relationship to sleep phase. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:108–12. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.09.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sell RE, Bardwell W, Palinkas L, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale J, Loredo JS. Ethnic differences in sleep-health knowledge. Sleep. 2009;32:A392. Abstract Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knutson KL. Association between sleep duration and body size differs among three Hispanic groups. Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23:138–41. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park Y, Quinn J, Florez K, Jacobson J, Neckerman K, Rundle A. Hispanic immigrant women's perspective on healthy foods and the New York City retail food environment: A mixed-method study. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomfohr LM, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE. Childhood socioeconomic status and race are associated with adult sleep. Behav Sleep Med. 2010;8:219–30. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2010.509236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grandner MA, Jackson NJ, Pigeon WR, Gooneratne NS, Patel NP. State and regional prevalence of sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:77–86. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2010. Health disparities strategic plan and budget fiscal years 2009-2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grandner MA, Hale L, Jackson N, Patel NP, Gooneratne NS, Troxel WM. Perceived racial discrimination as an independent predictor of sleep disturbance and daytime fatigue. Behav Sleep Med. 2012;10:235–49. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2012.654548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marmot M, Wilkinson R. Oxford: Oxford; 2005. Social determinants of health. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep continuity disturbance (unadjusted)

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep quality and daytime sleepiness (unadjusted)

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep continuity disturbance (adjusted)

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for associations between sociodemographics/socioeconomics and sleep quality and daytime sleepiness (adjusted)