Abstract

People with healthy eating identities report healthier diets and demonstrate greater receptivity to nutrition interventions, but other types of eating identity are likely important. We developed the Eating Identity Type Inventory (EITI) to assess affinity with four eating identity types; healthy, meat, picky, and emotional. This study assessed factorial validity, using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and established reliability and convergent validity of the EITI. In a telephone survey, 968 primary household food shoppers completed the EITI and a dietary questionnaire; 101 repeated the EITI approximately one month later. CFA revealed that an 11-item model provided acceptable fit (χ2= 206; df=38), CFI=.938, .NNFI=.925, RMSEA =.070; SRMR=.059). The EITI demonstrated acceptable internal consistencies with Cronbach alpha's ranging from .61-.82 and good test-retest reliability for healthy, emotional, and picky types (Pearson's correlations ranging from .78-.84). Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) used to assess relationships between eating identity type and diet analyses demonstrated significant hypothesized relationships between healthy eating identity and healthier dietary intake and meat and picky eating identities and less healthy dietary intake. The EITI could facilitate behavioral and cognitive research to yield important insights for ways to more effectively design messages, interventions, and policies to promote healthy dietary behaviors.

Introduction

Diets that do not conform to dietary guidelines are a major contributing factor to the burden of disease and health care costs in the United States and worldwide (Danaei et al., 2009; Danaei et al., 2010; Wang, Beydoun, Liang, Caballero, & Kumanyika, 2008). Decades of research have led to recognition of complex relationships between specific aspects of diet (e.g. sodium, fat, fiber, fruits and vegetables) and disease outcomes (e.g. hypertension, cardiovascular disease, certain cancers) (Chandalia et al., 2000; Hooper et al., 2012; Imamura, Jacques, Herrington, Dallal, & Lichtenstein, 2009; Lock, Pomerleau, Causer, Altmann, & McKee, 2005). The nutritional adequacy of diets among adults in the United States has been consistently poor over the last several decades as demonstrated by a consistent lack of conformity with dietary guidelines among the majority of the population (Blanck, Gillespie, Kimmons, Seymour, & Serdula, 2008; Guenther, Dodd, Reedy, & Krebs-Smith, 2006; King, Mainous III, Carnemolla, & Everett, 2009; Mellen, Gao, Vitolins, & Goff, 2008). According to national data, most American adults do not meet recommendations food based dietary guidelines (Kirkpatrick, Dood, Reedy, & Krebs-Smith, 2012) and less than 10% of adults meet recommended intake of fruit and vegetables (Kimmons, Gillespie, Seymour, Serdula, & Blanck, 2009). Other aspects of poor dietary intake, including inadequate consumption of fiber, whole grains, fruits and vegetables, and calcium and excessive consumption of foods high in saturated fat and sodium also contribute to the burden of disease in the population (Kant, Leitzmann, Park, Hollenbeck, & Schatzkin, 2009). Finding effective ways to help adults consume healthier diets that are consistent with dietary guidelines could reduce rates of nutrition-related chronic diseases (Watts, Hager, Toner, & Weber, 2011).

Despite our knowledge of the importance of a healthy diet, current approaches have been largely ineffective in promoting meaningful changes in dietary intake (Baranowski, Cullen, Nicklas, Thompson, & Baranowski, 2003; Guillaumie, Godin, & Vezina-Im, 2010; Hornik & Kelly, 2007; Kremers, 2010). Most dietary change research and interventions rely on behavioral science theories to gain an understanding of why people eat what they do and to inform the development of approaches that promote positive dietary changes (Baranowski, Cullen, & Baranowski, 1999; Baranowski et al., 2003). The poor performance of behavior change strategies is in part due to inadequate understanding of key psychosocial determinants of dietary intake (Baranowski et al., 2003; Guillaumie et al., 2010; Satia, Kristal, Patterson, Newhouser, & Trudeau, 2002; Shaikh, Yaroch, Nebeling, Yeh, & Resnicow, 2008). Existing psychosocial measures explain only a modest fraction of the variation in dietary intake, suggesting the need for new and innovative insights in this area (Baranowski et al., 1999; Guillaumie et al., 2010; Shaikh et al., 2008). Being able to better understand the determinants of dietary intake and to predict dietary intake based on measurement of these determinants is central to our efforts to develop effective policies, programs, and messages that promote meaningful and long-term dietary change (Baranowski et al., 2003; Orleans, 2000).

Healthy eating identity is a novel and promising psychosocial determinant of diet that could enhance our ability to understand motivators of and predict dietary intake (Abrams & Hogg, 1999; Allom & Mullan, 2012; Bisogni, Connors, Devine, & Sobal, 2002; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Devine, Connors, Bisogni, & Sobal, 1998; Devine, Sobal, Bisogni, & Connors, 1999; Fischler, 1988; Hopkins, Burrows, Bowen, & Tinker, 2001; Jones, 2005; Kendzierski, 2007; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004; Lindeman & Stark, 1999; Strachan & Brawley, 2009). Healthy eating identity is a domain-specific self-definition (self-identity) that is based on prior experience and emphasizes an aspect of the self that is important to the individual, in this case, healthy eating (Kendzierski & Costello, 2004). People who report a healthy eating identity are more likely to demonstrate healthier dietary intake and are more receptive to standard nutrition intervention approaches (Kendzierski, 2007; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004; Strachan & Brawley, 2008, 2009). One study recently demonstrated that having a healthy eating identity significantly predicted fruit and vegetables intake, independent of established psychosocial predictors of diet such as nutrition knowledge and self-efficacy for fruit and vegetable intake (Strachan & Brawley, 2009). The finding that those who identified themselves as healthy eaters were more receptive to a standard nutrition intervention messages suggests that eating identities may be predictive of eating behaviors.

Recently, several qualitative studies by our group and others have suggested there are multiple, commonly expressed types of eating identities, in addition to a healthy eating identity, that influence dietary intake. (Bisogni et al., 2002; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Blake, Jones, Pringle-Washington, & Ellison, 2010; Devine et al., 1999; Fox & Ward, 2008; Harmon, Blake, Armstead, & Hebert, 2013). Despite awareness of the influence of different types of eating identities on dietary intake, there are currently no valid and reliable instruments available to assess relationships between different combinations of eating identity types and key health behaviors and outcomes, including dietary intake. A better understanding of how different combinations of eating identity types are related to dietary intake would improve our understanding of relationships between food related cognition and behavior and enhance our ability to develop effective dietary change interventions (Bisogni et al., 2002; Jones, 2005). The availability of a valid and reliable measure of multiple eating identity types would provide researchers, clinicians, program planners, and policy makers with a useful instrument for gaining a better understanding of the relationship between a potentially important psychosocial determinant of diet, eating identity, and dietary intake.

To address this gap we developed the Eating Identity Type Inventory (EITI). The types of eating identities that are measured and wording of questions are based on a previously developed measure of healthy eating self-schema (Kendzierski & Costello, 2004) and qualitative work conducted in diverse populations (Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Blake et al., 2010). The purpose of this study was to assess the factorial validity of the EITI using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This study also sought to establish the convergent validity and reliability of this measure of eating identity types. It was expected that high healthy eating identity scores would correlate positively with indicators of healthy dietary intake while higher emotional, meat, and picky scores would correlate negatively with indicators of healthy dietary intake.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study included a geographically based sample of 968 adults who were the primary food shoppers of their household in an eight-county study region in South Carolina. These data were collected as part of a larger study of relationships between perceptions of the food environment and validated objective (GIS-based) availability and accessibility measures, shopping behaviors, dietary intake, and other psychosocial factors (Liese et al., 2013). The study area consisted of a contiguous geographical area encompassing a total of eight counties (seven rural and one urban) in the Midlands region of the state of South Carolina.

Procedures

All study activities were approved by the University's Institutional Review Board. Prior to initiation of the telephone survey, the entire questionnaire had been cognitively tested with 6 focus groups of about 8 participants each to obtain insight into question interpretation. Focus group participants were recruited from urban, suburban and rural settings, with two groups in each.

Participant selection for the telephone survey was conducted using a simple random sampling scheme of listed landline phone numbers within 64 eligible zip codes of the eight-county study region. This geographic sampling scheme was needed for the overarching aims of the study. Recruitment calls were made by the USC Survey Research Laboratory (SRL). USC SRL staff are highly trained and experienced in conducting telephone based research. Respondents were screened to meet the following eligibility criteria; a) at least 18 years, b) self-reported primary household food shopper, and c) English speaking. Introductory letters were sent to respondents in advance of telephone calls. The survey consisted of six separate sections that included the following: (1) perceptions of the food environment, (2) primary and secondary food shopping behavior, (3) eating out behavior, (4) EITI, (5) dietary behaviors, and (6) demographic characteristics. The entire survey took approximately 20 minutes to complete. A total of 903 who provided responses to all of the eating identity questions served as analytic sample for the CFA and 817 who provided response to all eating identity, dietary intake, and demographic questions served as the analytic sample for the OLS analysis. In addition, 101 respondents (who had been randomly selected in the larger survey) participated in a follow-up interview to assess reliability of selected measures. A total of 94 of respondents completed the second administration of the EITI. The average time between survey administrations was 35 days (SD = 8).

Measurement and variables

Eating Identity Type Inventory (EITI)

We assessed eating identity using a 12-item instrument that differentiates eating identity types. Participants were asked to indicate how much they agreed with each of the 12 items on a scale of 1 to 5 with one being “strongly agree” and five “strongly disagree” (Table 1). These twelve items were used to construct scores for four hypothesized eating identity types; healthy, emotional, meat and picky (Bisogni et al., 2002; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Blake et al., 2010; Caplan, 1997; Devine et al., 1999; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004). Each of the items was rescaled for analysis so that higher values indicated greater affinity for the eating identity type. The administration of the 12-item eating identity instrument was conducted using four randomly determined question order sequences for the main telephone survey to control for item order effect. For the reliability study, participants were asked to respond to questions using the same question order sequence used in the first interview.

Table 1. Description of the Eating identity type inventory (EITI) items a, b, c.

| Type | EITI Items | |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy | H1 | I am a healthy eater |

|

|

||

| H2 | I am someone who eats in a nutritious manner | |

|

|

||

| H3 | I am someone who is careful about what I eat | |

|

| ||

| Emotional | E1 | I am someone who eats more when sad/depressed |

|

|

||

| E2 | I am someone who eats more when stressed/anxious | |

|

|

||

| E3 | I am an overeater | |

|

| ||

| Meat | M1 | I am a meat eater |

|

|

||

| M2 | I am someone who likes meat with every meal | |

|

|

||

| M3 | I am a junk food eater | |

|

| ||

| Picky | P1 | I am a picky eater |

|

|

||

| P2 | I am someone who likes to try new foods | |

|

|

||

| P3 | I am someone who likes to eat a lot of different things | |

Respondents were instructed to indicate their level of agreement with each statement on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being strongly agree and five being strongly disagree

The administration of the 12-item eating identity instrument was conducted using four randomly determined question order sequences for the main telephone survey.

all items were recoded for analysis so that higher scores corresponded to greater affinity with the types. P2 and P3 were reversed to assess picky eating identity in the way they were phrased so they were not recoded.

Dietary Intake

Dietary intake was assessed using the 17-item Multifactor Screener developed for the 2000 National Health Interview Survey (Thompson et al., 2005). This instrument was specifically developed to provide valid estimates of three key dietary variables, percentage of energy from fat, grams of fiber, and servings of fruits and vegetables, based on a short screener interview assessing only a limited number of foods. It has been shown to provide very good estimates of true intakes of fruits and vegetables, fiber and percentage of energy from fat, with correlation coefficients between screener estimates and three 24 hour dietary recalls ranging from 0.5 to 0.8. (Thompson et al., 2004). Estimates of usual intake of these three dietary variables were calculated for this study by applying to the screener responses the scoring procedures previously described in detail (National Cancer Institute, 2012; Thompson et al., 2005).

Data Analysis

Testing factorial validity

The first step in the analysis was to assess the factorial validity of the EITI. We hypothesized that the 12-item EITI included four distinct factors representing healthy, emotional, meat, and picky eating identity types. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess whether the four-factor hypothesized model fit the data, using maximum likelihood estimation (AMOS 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The indicators used to evaluate model fit included the minimum fit function chi-square (χ2) test, the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normed fit index (NNFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMS). Small χ2 values indicate a good fit, reflecting a small discrepancy between the structure of the observed data and the hypothesized model but this indicator is sensitive to sample size so is often used to assess model fit in conjunction with other fit statistics. Bentler's CFI and the NNFI indices are designed to compare the hypothesized model to a ‘null’ or worst fitting model, taking into account model complexity, and indicate an acceptable model fit with values >0.90 and good fit with values >0.95. The RMSEA reflects the extent to which the model fit approximates a reasonably fit model and indicates an acceptable model fit with values <0.08 and a good model fit with values <0.05. The SRMR is a standardized summary of the average covariance residuals. When the model fit is perfect, the SRMR is zero while a SRMR value of close to 0.08 is indicative of a relatively good fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999). To identify the most parsimonious and theoretically applicable model, the feasibility of parameter estimates and model misspecification were assessed in addition to model fit indices. Statistical significance of parameter estimates, item loadings, and the residual matrix and modification indices were reviewed to determine whether modifications to the model should be made. Items with factor loadings below 0.40 were deleted from the model (Birch et al., 2001).

Convergent validity

Next, the best fitting model derived from the CFA procedure was used to assess relationships between scores for each eating identity type and dietary intake. This model included 11-items and four factors representing each of the four eating identity types (more details on this best fitting model are presented in the Results). Individual eating identity items were summed for each type and divided by the number of items in each type to create four separate scores. We hypothesized that scores for each eating identity type would be associated with dietary intake with healthy eating identity scores being positively associated with healthier (e.g. higher fruit, vegetable and fiber intake) and negatively associated with less healthy dietary intake and (percentage of kcal from fat) and emotional, meat, and picky eating identity scores being negatively associated with healthier and positively associated with less healthy dietary intake. Convergent validity was determined by assessing the hypothesized degree to which each eating identity type (healthy, emotional, picky, and meat) corresponded with each of our dietary intake measures - percentage of total kilocalories from fat, grams of fiber per day, and number of servings of fruits and vegetables per day via OLS regression. Covariates included gender (male, female), race (white, non-white), age (continuous, range from 19 to 95), education (high school completion or not) and urban residence (yes/no). To demonstrate the influence of each eating identity type, without controlling for the other types, we examined four models in which only one eating identity type score was included in addition to the listed covariates. We also examined a model in which all four eating identity types were included simultaneously which allowed us to examine the unique influence of each eating identity type on our dietary outcomes.

Reliability testing

Descriptive statistics were used to describe scores for each eating identity type based on the final model derived from the CFA procedure. Internal consistency of each of the four eating identity types was assessed using Cronbach's alphas. Values >0.60 were considered acceptable and values >0.70 desirable (Cronbach, 1951). Additionally, test-retest reliability for each eating identity type score of the final model derived from CFA was assessed using 94 observations with complete data from the subsample of 101 reliability sub-study participants with Pearson product-moment correlations between two data points (Rodgers & Nicewander, 1988). A p -value of <0.05 was considered significant and correlations coefficients >0.80 were acceptable.

Results

The results presented below demonstrate the validity and reliability of the EITI. Descriptive statistics for the 817 participants that completed the eating identity, dietary, and demographics questions and the 94 participants who completed a retest of the eating identity questionnaire are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Characteristics of study participants in the full and test-retest samples.

| Characteristic | Full sample a (n=817) | Test-retest sample b (n=94) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, sd) | 57.2 (14.5) | 59.1 (11.8) |

|

| ||

| Gender (% female) | 79.4 | 79.8 |

|

| ||

| Race (% minority) | 32.7 | 32.3 |

|

| ||

| Live with partner (%) | 64.2 | 69.9 |

|

| ||

| More than high school education (%) | 54.2 | 61.3 |

|

| ||

| Income (% mid/high ≥ $40,000 per year) | 57.9 | 56.8 |

|

| ||

| Employment (% yes) | 42.9 | 32.3 |

|

| ||

| SNAP recipient (% yes) | 8.5 | 6.4 |

|

| ||

| Persons in household >18 years (mean, sd) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.8) |

|

| ||

| Persons in household <18 years (mean, sd) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.7) |

|

| ||

| Poverty status (% below) | 25.7 | 21.0 |

|

| ||

| Urban (% yes) | 22.9 | 25.3 |

|

| ||

| Percent Kcal from fat (mean, sd) | 34.3 (4.5) | 34.7 (3.8) |

|

| ||

| Total grams fiber (mean, sd) | 12.9 (4.8) | 12.4 (4.3) |

|

| ||

| Servings f/v (mean, sd) | 4.5 (1.6) | 4.3 (1.5) |

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis

Because previous studies have shown that the hypothesis-testing methods provide a stronger theoretically applicable model than other methods of factor analysis like principle component analysis, we chose to use confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess model fit and refine the measure. The hypothesized four factor structure with twelve items was tested (Model 1) using the full sample of participants who answered all items in the EITI (n=903). The fit indices for Model 1 showed a poor fit of the model, as indicated by the RMSEA, CFI, NFI, and SRMR (Table 3). Moreover, one item had a factor loading less than .30. Using standard CFA procedures, we excluded this one item with a low factor loading and again assessed model fit. Model 2 with 4 factors and 11 items demonstrated an improved fit, as indicated by the RMSEA (.070), CFI (.937), NNFI (.925), and SRMR (.058). Furthermore, the change of χ2 indicated that Model 2 fit the data better than Model 1 (Table 3). Thus, all subsequent analyses presented below were based on Model 2, the 11-item, four factor EITI.

Table 3. Goodness of fit indices of models tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

| Model specifications | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | NNFI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: 12 items, 4 factorsa | 418.912 | 48 | .093 | .873 | .874 | .093 |

|

| ||||||

| Model 2: 11 items, 4 factors | 205.735 | 38 | .070 | .938 | .925 | .058 |

Model 1: hypothesized model

Characteristics of the Eating Identity Type Inventory (EITI)

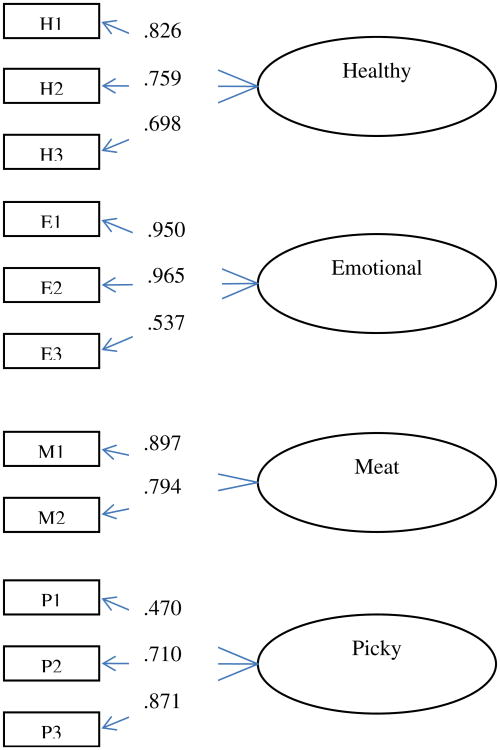

Factor item loadings for each of the items on the 11-item EITI with four hypothesized types are depicted in Figure 1. The values of the factor-item loadings ranged from 0.465 to 0.965 and all were significantly different from zero (p<.05), therefore all were meaningful indicators of corresponding factors (i.e., eating identity types). Because we hypothesized that the EITI is in fact a multi-dimensional attribute, we evaluated the correlations between the four hypothesized factors using the final model. Correlations between the four factors of the 11-item EITI derived from the CFA procedure are presented in Table 4. Modest correlations between factors were observed. The highest factor correlations were between healthy and other eating identity scores, meaning that those who expressed greater affinity with healthy eating identity statements were more likely to report lower affinity with emotional eating. (r=-.276), meat eating (r=-.204) and picky eating (r=-.225) identity scores indicating that those who see themselves as healthy eaters are less likely to also identify as emotional, meat, or picky eaters. Meat eating identity was also positively associated with emotional eating identity.

Figure 1.

Standardized estimated factor-item loadings from Model 2 in the Confirmatory Factor Analytic procedure showing eleven items and four factors (factor-factor correlations presented in Table 4). Item descriptions are shown in Table 1. The shapes in the figure represent as follows; ovals: latent variables (factors), rectangles: measured variables; one-headed arrow: factor loading.

Table 4. Estimated factor-factor correlations among eating identity types derived using the eleven-item, four-factor model in the Confirmatory Factor Analytic procedure and correlations between factors and dietary intake variables.

| Factor a | Healthy | Emotional | Meat | Picky | Fat (%kcal) | Fiber (gm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | — | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Emotional | -.276** | — | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Meat | -.204** | .113** | — | |||

|

| ||||||

| Picky | -.225** | -.114** | -.115** | — | ||

|

| ||||||

| Fat (%kcal) | -.255*** | .089** | .278*** | -.039 | — | |

|

| ||||||

| Fiber (gm) | .198*** | -.051 | -.017 | -.173*** | .004 | — |

|

| ||||||

| F/V (servings) | .347*** | -.070* | -.071* | -.212*** | -.151*** | .641*** |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Healthy, Emotional, and Picky factors derived using 3 items for each; meat factor derived from 2 items

Table 5 presents results from the reliability analyses of the eleven-item, four-factor EITI showing internal consistency and test-retest statistics for each eating identity type. Internal consistency was demonstrated by assessing consistency of responses to items within each type for the full sample (n=903). Cronbach's alphas demonstrated good internal consistency for healthy eating identity (0.82) and emotional eating identity (0.76) and acceptable internal consistency for meat eating identity (0.68) and picky eating identity (0.61) types. Pearson's product moment correlation coefficients were used to assess test-retest reliability with the subsample that repeated the EITI approximately one month after completing the baseline survey (n=94). Test-retest reliability was acceptable for healthy, emotional, and picky eating identity types (0.78, 0.84, and 0.78 respectively) and significant but marginal for the meat eating identity type (0.66).

Table 5. Reliability of the eleven-item, four-factor EITI: Eating Identity Type descriptive statistics and internal consistency for the full sample (n=903) and test-retest reliability in the subsample.

| Internal Consisteny (n=903) | Test-Retest (n=94) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Type score | ||||

| EITI type a | Mean (SD) b | Range | Cronbach's alpha c | Pearson's test-retest d |

| Healthy | 3.68 (0.84) | 1-5 | 0.82 | 0.78*** |

|

| ||||

| Emotional | 2.52 (0.92) | 1-5 | 0.76 | 0.84*** |

|

| ||||

| Meat | 3.12 (1.02) | 1-5 | 0.68 | 0.66*** |

|

| ||||

| Picky | 2.50 (0.87) | 1-5 | 0.61 | 0.78*** |

p < .0001

Reliability of the eleven-item, four-factor EITI was used to calculate scores for each type.

Scores for the Healthy, Emotional, and Picky types were derived by summing responses for the 3 items corresponding to each type and dividing by 3; type scores for the meat type were derived by summing responses for meat items and dividing by 2.

Internal consistency was assessed for each EITI type using the raw data from the total sample of 903 participants.

Test-retest reliability was assessed for each EITI type using the data from a subsample of 94 who repeated the eating identity measure approximately one month after the first administration.

Convergent validity of the EITI using the 11-item, four factor model is illustrated in Tables 4 and 6. Table 4 presents correlations between each eating identity type and three dietary intake variables (i.e., unadjusted bivariate relationships) whereas Table 6 presents results of OLS models in which eating identity types were regressed on the three dietary intake measures, while controlling for gender, race, education, age, and urban residence. Based on models in which each eating identity type was examined alone, healthy, emotional, and meat eating identities predicted a significant proportion of the variation for percent fat intake (ranging from 1 to 4%) while healthy, meat, and picky eating identities predicted a significant proportion of the variation for fiber and F & V intake (ranging from 1 to 10 %). When all four eating identity types were included in the model, the unique contributions of healthy and meat scores continued to explain a significant proportion of the variation in percent fat (ranging from 2 to 3%) and healthy, picky, and meat scores predicted a significant proportion of the variation for fiber and F & V (ranging from 1 to 7%).

Table 6. Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) model results depicting associations between Eating Identity types alone and with other types included in the model and % kcal from fat, grams of fiber, and servings of fruits and vegetables (n=817) a.

| Eating Identity Type and model inclusion status b | % Fat Kcal | Fiber (grams) | F & V(servings) c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | Unique R2 | β | R2e | Unique R2 | β | R2 | Unique R2 | ||

| Healthy | Alone d | -1.02*** | 0.08*** | 0.03 | 0.95*** | 0.15*** | 0.03 | 0.60*** | 0.15*** | 0.10 |

| +all types | -0.87*** | 0.11*** | 0.02 | 0.86*** | 0.16*** | 0.02 | 0.55*** | 0.18*** | 0.07 | |

| Emotional | Alone | 0.43* | 0.05*** | 0.01 | -0.03 | 0.12*** | 0.00 | -0.08 | 0.06*** | 0.00 |

| +all types | 0.08 | 0.11*** | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.16*** | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.18*** | 0.00 | |

| Meat | Alone | 0.92*** | 0.08*** | 0.04 | -0.41* | 0.13*** | 0.01 | -0.17** | 0.07*** | 0.01 |

| +all types | 0.81*** | 0.11*** | 0.03 | -0.37* | 0.16*** | 0.01 | -0.13* | 0.18*** | 0.01 | |

| Picky | Alone | 0.01 | 0.05*** | 0.00 | -0.66** | 0.14*** | 0.01 | -0.37*** | 0.10*** | 0.04 |

| +all types | -0.06 | 0.11*** | 0.00 | -0.52** | 0.16*** | 0.01 | -0.28*** | 0.18*** | 0.02 | |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

A total of 817 participants had complete data for all eating identity, dietary intake questions, and demographic characteristics. All models controlled for gender, race, education, age, and urban residence.

Eating Identity type scores were based on the eleven-item, four-factor model and calculated by summing all questions corresponding to each type and dividing by the number of items in that type (3 for healthy emotional and picky; 2 for meat)

Fruit and vegetables does not include fries

The first row for each type shows results from the OLS model with only the labeled eating identity type score and control variables included in the model. The +all types row shows results from OLS models with the labeled eating identity type score, control variables, and all other eating identity type scores included in the model.

Gender explained a larger proportion of the variation, 8%, than any of the eating identity types

Discussion

To develop approaches for the adoption of more healthful diets that are meaningful to target audiences, it is imperative to be able to measure multiple types of identity likely to be associated with dietary intake. Whereas some progress has been made in the conceptualization and measurement of healthy eating identity, there is a dearth of research on ways to measure other important types of eating identity. This study demonstrates the validity and reliability of a measure of eating identity that assesses multiple types simultaneously. The EITI was based on multiple studies in diverse populations (Bisogni et al., 2002; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Blake et al., 2010; Caplan, 1997; Devine et al., 1999; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004). Confirmatory factor analysis revealed that the 11-item, four-factor model fit the data well which provides preliminary evidence in support of our hypothesis that there are at least four distinct types of eating identity. Furthermore, eating identity types created from the final model demonstrated acceptable reliability in a subsample of 94 participants. Most importantly, our results indicate that the EITI explained a significant amount of the variation in dietary intake and that separate eating identity types were associated with several hypothesized dietary intake behaviors, which suggests convergent validity.

Identities related to eating have been the focus of many studies that present eating from the perspective of specific demographic or behavioral categories such as age, gender, ethnicity, region, vegetarianism, beef eating, organic eating, disease, weight, body image, or healthiness. These studies have tended to emphasize dichotomies; whether one does or does not express affinity for a particular type of eating identity (e.g. healthy or unhealthy). (Bisogni et al., 2002; Caplan, 1997; Fox & Ward, 2008; Jabs, Sobal, & Devine, 2000; Jones, 2005; Kalcik, 1984; Lindeman & Stark, 1999; Markus, 1990; Milton, 1997; Saddala & Burroughs, 1981; Sparks & Shepherd, 1992; Strachan & Brawley, 2009; Willetts, 1997). The findings presented here advance current research by moving beyond single types or dichotomized eating identity concepts towards a theoretically grounded instrument that captures multiple aspects of eating identity simultaneously.

The EITI is a first attempt to measure multiple types of eating identity and examine relationships between these types and dietary behavior concurrently. It has been demonstrated previously that people who describe themselves as healthy eaters are more likely to report healthy dietary behaviors and are more receptive to standard nutrition intervention approaches (Bisogni et al., 2002; Devine et al., 1998; Devine et al., 1999; Kendzierski, 2007; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004; Strachan & Brawley, 2009). Other types of eating identity, such as pickiness, have also previously been shown to influence food choice behaviors (Bisogni et al., 2002; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Devine et al., 1999; Jabs et al., 2000), but these different types of eating identities have been evaluated independently from one another (Fox & Ward, 2008; Jabs et al., 2000; Jones, 2005; Milton, 1997; Strachan & Brawley, 2009; Willetts, 1997). Findings presented here demonstrate significant plausible relationships between four types of eating identity and different aspects of dietary intake. For example, we found that higher healthy eating identity scores were associated with healthier dietary intake (e.g. higher intakes of servings of fruits and vegetables, grams of fiber and lower percentage of total kilocalories from fat) whereas picky and meat eating identities were associated with less healthy dietary intake.

Current understanding of dietary patterns and why people eat as they do could be enhanced through exploration of relationships between eating identity and affinity for particular foods, food groups, or eating patterns (Hu, 2002; Liese, Nichols, Sun, D'Agostino, & Haffner, 2009) and changes in these patterns over time. Monitoring eating identity and dietary changes over time could provide evidence of cognitive changes that correspond to long-term maintenance of healthy dietary behaviors. For example, does participation in a particular intervention lead to changes in one's eating identity that precedes long-term dietary behavior change? Or do changes in dietary intake lead to changes in eating identity? Such insights would greatly improve our ability to capture intervention effects that may precede those dietary changes that occur long after an intervention has ended. On the other hand, is eating identity a construct that is amenable to change at all (a state) or is it a stable trait that could be used in targeting and tailoring of messages? The EITI would also allow for exploration of the changeability versus stability of eating identity types and provide guidance on the value of designing interventions that focus on inculcating particular eating identities to promote meaningful long term changes in dietary intake, and ultimately reduce obesity and improve health. (Bisogni et al., 2007; Jastran, Bisogni, Sobal, Blake, & Devine, 2009; Orleans, 2000)

There are several limitations of this study that should be addressed in future studies. This study utilized a comprehensive sampling frame that captured rural and urban communities, racial and ethnic diversity, and SES variation, however, the utilization of land-line based phone services resulted in an over sampling of older participants. The EITI demonstrated acceptable internal consistency for all four types and acceptable test-retest reliability for three types but marginal test-retest reliability for measurement of meat eating identity. It is possible that healthy, emotional, and picky eating identities are more stable over time whereas meat eating or picky eating identities are more labile. However, it is more likely that the number of items used to assess meat eating identity may have been too few in number. When the one item was deleted from the meat eating type only two remained. Previous formative work on eating identities yielded multiple candidate items that were not included in the instrument tested here (Blake et al., 2010). Addition of some of these candidate items may improve the reliability and strengthen the fit of the model and the utility of the EITI for predicting dietary behavior in different settings and populations.

Results demonstrating hypothesized relationships with dietary intake provide evidence for concurrent validity but need to be interpreted with caution. The instrument used to assess dietary intake relied on self-reported dietary intake. Some have argued that the use of self-reported behavioral measures may be prone to biases, including social desirability bias (Hebert et al., 2008). We are unable to determine whether levels of social desirability bias were associated in different ways to each eating identity type. It is possible that those with a healthy eating identity may be more likely to report healthier diets regardless of actual intake, which, if true, would result in differential misclassification. Therefore, future studies using the EITI should examine relationships between eating identity types, social desirability, self-reported dietary intake and objectively measured dietary intake to confirm or refute our observed associations. Results for associations with fiber intake suggest that gender is more strongly associated with dietary fiber intake than the EITI. Upon further analysis of data separately by gender we determined that the EITI was a better predictor of fiber intake in women than men but the directions of association between each eating identity type were similar. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of this analysis does not permit determination of causality. We are unable to definitively determine whether identity predicts diet or whether dietary intake shapes identity. Adult dietary habits and identity both develop over a the course of one's lifetime and their development is interconnected (Bisogni et al., 2002; Devine et al., 1998; Jabs et al., 2000). Based on numerous qualitative studies we believe it is plausible to conceptualize current identity predicting future behavior rather than the reverse (Bisogni et al., 2002; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Blake et al., 2010; Devine et al., 1999; Harmon et al., 2013), however, future studies should be conducted to examine these relationships. Despite these limitations, this instrument should help researchers better understand how eating identities are related to dietary behaviors, receptivity to diet messages, and response to environments and interventions.

Behavioral science theories and methods are used to understand why people eat as they do and to inform the development of programs that promote healthy dietary behavior (Baranowski et al., 1999; Baranowski et al., 2003). Understanding of the basic mechanisms that explain dietary behaviors is central to our efforts to develop effective policies, programs, and messages that promote such meaningful and long-term dietary change (Baranowski et al., 2003; Orleans, 2000). However, our ability to predict dietary behavior is constrained by our understanding of the psychosocial factors that mediate relationships between exposure (e.g. environments, programs, messages) and dietary behavior. (Baranowski et al., 1999; Guillaumie et al., 2010; Lockwood, DeFrancesco, Elliot, Beresford, & Toobert, 2010; Shaikh et al., 2008) Eating identity is a novel and promising psychosocial determinant of diet. As mentioned above, current findings demonstrate significant and plausible relationships between types of eating identity assessed by the EITI and dietary intake among adults who are the primary household food shoppers. Being able to measure multiple types of eating identity simultaneously could greatly enhance our ability to understand and predict dietary behavior. (Allom & Mullan, 2012; Blake & Bisogni, 2003; Blake et al., 2010; Hopkins et al., 2001; Kendzierski, 2007; Kendzierski & Costello, 2004; Lindeman & Stark, 1999; Strachan & Brawley, 2009).

The EITI provides researchers, program planners, and policy makers with a promising instrument for measuring eating identity, an important psychosocial determinant of diet. The EITI may be useful for facilitating behavioral and cognitive research to yield important insights for ways to more effectively design messages, interventions, and policies to promote positive dietary behavior change. Finally, the EITI may be useful in future etiological research, research exploring dietary behavior and development of interventions in different contexts.

Highlights.

Healthy eating identity is known to be associated with healthy diet

Other types of eating identity are also important for understanding diet behavior

The EITI assesses four eating identity types; healthy, meat, picky, and emotional

The EITI demonstrates acceptable fit, internal consistency, and convergent validity

The EITI demonstrates convergent validity with hypothesized aspects of diet

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant R21CA132133-02S1 from the National Cancer Institute. The authors would like to thank Timothy L. Barnes for data management and statistical programming. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Christine E. Blake, 800 Sumter Street Columbia, SC, 29208, USA.

Bethany A. Bell, 820 South Main Street Columbia, SC 29208 USA.

Darcy Freedman, DeSaussure Hall Columbia, SC 29208 USA.

Natalie Colabianchi, Institute for Social Research Ann Arbor, MI 48106 USA.

Angela D. Liese, 921 Assembly Street Columbia, SC 29208, USA.

References

- Abrams D, Hogg MA, editors. Social identity and social cognition. Oxford: Blackwell; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Allom V, Mullan B. Self-regulation versus habit: the influence of self-schema on fruit and vegetable consumption. Psychology & Health. 2012;2:7–24. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.605138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Baranowski J. Psychosocial correlates of dietary intake: advancing dietary intervention. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1999;19:17–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Cullen KW, Nicklas T, Thompson D, Baranowski J. Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts? Obesity. 2003;11(10S):23S–43S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni CA, Connors M, Devine CM, Sobal J. Who we are and how we eat: a qualitative study of identities in food choice. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2002;34:128–139. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni CA, Falk LW, Madore E, Blake CE, Jastran M, Sobal J, Devine CM. Dimensions of everyday eating and drinking episodes. Appetite. 2007;48(2):218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA. Personal and family food choice schemas of rural women in Upstate New York. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2003;35(6):282–293. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Jones SJ, Pringle-Washington A, Ellison J. Assessing eating identities of rural African American's in the southern US; Paper presented at the International Society for Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity (ISBNPA); Minneapolis, MN. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Liese AD, Nichols M, Jones SJ, Freedman D, Colabianchi N. Measuring the dimensions of eating identity: internal consistency and test-retest reliability of a short 12-item tool; Paper presented at the Experimental Biology, Annual Meeting of the American Society for Nutrition (ASN); Washington, DC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Kimmons JE, Seymour JD, Serdula MK. Trends in Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Among U.S. Men and Women, 1994-2005. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2008;5(2):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan P, editor. Food, health, and identity. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chandalia M, Garg A, Lutjohann D, von Bergmann K, Grundy SM, Brinkley LJ. Beneficial Effects of High Dietary Fiber Intake in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(19):1392–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJL, Ezzati M. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. Public Library of Science (PLoS) Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Rimm EB, Oza S, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJL, Ezzati M. The promise of prevention: the effects of four preventable risk factors on national life expectancy and life expectancy disparities by race and county in the United States. Public Library of Science (PLoS) Med. 2010;7(3):e1000248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Connors M, Bisogni CA, Sobal J. Life-course influences on fruit and vegetable trajectories: A qualitative analysis of food choices. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1998;31:361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA, Connors M. Food choices in three ethnic groups: interactions of ideals, identities and roles. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1999;31(2):86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler C. Food, self and identity. Social Science Information. 1988;27(2):275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, Ward KJ. You are what you eat? vegetarianism, health and identity. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66(12):2585–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans Eat Much Less than Recommended Amounts of Fruits and Vegetables. Journal of The American Dietetic Association. 2006;106(9):1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumie L, Godin G, Vezina-Im LA. Psychosocial determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in adult population: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon BE, Blake CE, Armstead CA, Hebert JR. Intersection of Identities: Food, Role, and the African-American Pastor. Appetite. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Moore HJ, Douthwaite W, Skeaff CM, Summerbell CD. Effect of reducing total fat intake on body weight: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. British Medical Journal. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins S, Burrows E, Bowen DJ, Tinker LF. Differences in eating pattern labels between maintainers and nonmaintainers in the Women's Health Initiative. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2001;33(5):278–283. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R, Kelly B. Communication and Diet: An overview of experience and principles. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2007;39:S5–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2002;13(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200202000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura F, Jacques PF, Herrington DM, Dallal GE, Lichtenstein AH. Adherence to 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans is associated with a reduced progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis in women with established coronary artery disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;90(1):193–201. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J, Sobal J, Devine CM. Managing vegetarianism: Identities, norms, and interactions. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2000;39:375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Jastran MM, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Blake C, Devine CM. Eating routines. embedded, value based, modifiable, and reflective. Appetite. 2009;52(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MO. Food choice, symbolism, and identity: bread-and-butter issues for folkloristics and nutrition studies (American Folklore Society Presidential Address, October 2005) Journal of American Folklore. 2005;120(476):129–177. [Google Scholar]

- Kalcik S. Ethnic foodways in America: symbol and the performance of identity. In: Brown LK, Mussell K, editors. Ethnic and regional foodways in the United States: the performance of group identity. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press; 1984. pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kant AK, Leitzmann MF, Park Y, Hollenbeck A, Schatzkin A. Patterns of Recommended Dietary Behaviors Predict Subsequent Risk of Mortality in a Large Cohort of Men and Women in the United States. The Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139(7):1374–1380. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.104505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D. A self-schema approach to healthy eating. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2007;12(6):350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D, Costello MC. Healthy eating self-schema and nutrition behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2004;24(12):2437–2245. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmons J, Gillespie C, Seymour J, Serdula M, Blanck H. Fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents and adults in the United States: percentage meeting individualized recommendations. Medscape Journal of Medicine. 2009;11(1):26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DE, Mainous AG, III, Carnemolla M, Everett CJ. Adherence to Healthy Lifestyle Habits in US Adults, 1988-2006. The American Journal of Medicine. 2009;122(6):528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Income and Race/Ethnicity Are Associated with Adherence to Food-Based Dietary Guidance among US Adults and Children. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(5):624–635.e626. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremers S. Theory and practice in the study of influences on energy balance-related behaviors. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liese AD, Bell BA, Barnes TL, Colabianchi N, Hibbert JD, Blake CE, Freedman DA. Environmental influences on fruit and vegetable intake: results from a path analytic model. Journal of Nutrition. 2013 doi: 10.1017/S1368980013002930. in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liese AD, Nichols M, Sun X, D'Agostino RB, Haffner SM. Adherence to the DASH Diet Is Inversely Associated With Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1434–1436. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeman M, Stark K. Pleasure, pursuit of health, or negotiation of identity? personality correlates of food choice motives among young and middle-aged women. Appetite. 1999;33:141–161. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M. The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2005;83:100–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood CM, DeFrancesco CA, Elliot DL, Beresford SAA, Toobert DJ. Mediation analyses: applications in nutrition research and reading the literature. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2010;110(5):753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus H. Unresolved issues of self-representation. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1990;14(2):241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mellen PB, Gao SK, Vitolins MZ, Goff DC., Jr Deteriorating Dietary Habits Among Adults With Hypertension: DASH Dietary Accordance, NHANES 1988-1994 and 1999-2004. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(3):308–314. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton K. Real men don't eat deer. Discover. 1997;18:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Multifactor Screener: Scoring Procedures. 2012 http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/surveys/nhis/multifactor/scoring.html. Retrieved on October 1st,2012.

- Orleans CT. Promoting the maintenance of health behavior change: Recommendations for the next generation of research and practice. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1):76–83. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saddala E, Burroughs J. Profiles in eating: sexy vegetarians and other diet-based social stereotypes. Psychology Today. 1981;15:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Satia JA, Kristal AR, Patterson RE, Newhouser ML, Trudeau E. Psychosocial factors and dietary habits associated with vegetable consumption. Nutrition. 2002;18:247–254. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh AR, Yaroch AL, Nebeling L, Yeh MC, Resnicow K. Psychosocial predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adults: a review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34(6):535–543.e511. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks P, Shepherd R. Self-identity and the Theory of Planned Behavior: assessing the role of identification with “Green Consumerism”. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1992;55(4):388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Strachan SM, Brawley LR. Reactions to a perceived challenge to identity: a focus on exercise and healthy eating. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(5):575–588. doi: 10.1177/1359105308090930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan SM, Brawley LR. Healthy-eater identity and self-efficacy predict healthy eating behavior: A prospective view. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(5):684–695. doi: 10.1177/1359105309104915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, Kahle LL, Schatzkin A, Kipnis V. Performance of a short tool to assess dietary intakes of fruits and vegetables, percentage energy from fat and fibre. Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7(08):1097–1106. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, McNeel T, Berrigan D, Kipnis V. Dietary intake estimates in the National Health Interview Survey, 2000: Methodology, results, and interpretation. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(3):352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will All Americans Become Overweight or Obese? Estimating the Progression and Cost of the US Obesity Epidemic. Obesity. 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts ML, Hager MH, Toner CD, Weber JA. The art of translating nutritional science into dietary guidance: history and evolution of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Nutrition Reviews. 2011;69(7):404–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willetts A. ‘Bacon sandwiches got the better of me’: meat-eating and vegetarianism in South-East London. In: Caplan P, editor. Food, health, and identity. London: Routledge; 1997. pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]