Abstract

Aims: The aim of the study was to explore neurometabolic and associated cognitive characteristics of patients with polysubstance use (PSU) in comparison with patients with predominant alcohol use using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Methods: Brain metabolite concentrations were examined in lobar and subcortical brain regions of three age-matched groups: 1-month-abstinent alcohol-dependent PSU, 1-month-abstinent individuals dependent on alcohol alone (ALC) and light drinking controls (CON). Neuropsychological testing assessed cognitive function. Results: While CON and ALC had similar metabolite levels, persistent metabolic abnormalities (primarily higher myo-inositol) were present in temporal gray matter, cerebellar vermis and lenticular nuclei of PSU. Moreover, lower cortical gray matter concentration of the neuronal marker N-acetylaspartate within PSU correlated with higher cocaine (but not alcohol) use quantities and with a reduced cognitive processing speed. Conclusions: These metabolite group differences reflect cellular/astroglial injury and/or dysfunction in alcohol-dependent PSU. Associations of other metabolite concentrations with neurocognitive performance suggest their functional relevance. The metabolic alterations in PSU may represent polydrug abuse biomarkers and/or potential targets for pharmacological and behavioral PSU-specific treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) methods enable the non-invasive quantification of metabolites from various brain regions. It permits the assessment of neurophysiological correlates of a disease/condition that may precede any associated gross morphological changes and has become an invaluable tool in understanding the neurobiological correlates of addictive disorders. Single-voxel 1H MRS usually measures brain metabolite concentrations in a defined region of interest (ROI) that need to be chosen a priori, while multi-slice spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) simultaneously acquires many spectra from known locations throughout the brain; thus, MRSI and MRS are complementary clinical research tools with different experimental strengths.

Much MRS research in addiction has focused on describing alterations in concentrations of different brain metabolites in alcohol-dependent individuals (ALC) (Sullivan et al., 2000; Durazzo and Meyerhoff, 2007; Buhler and Mann, 2011; Mon et al., 2012). Recently, we observed that the concentrations of markers of neuronal integrity (N-acetylaspartate, NAA) and cellular bioenergetics (creatine + phosphocreatine, Cr) as well as the neuromodulator/transmitter glutamate (Glu) in the anterior cingulate cortex of 9-day-abstinent ALC were significantly lower than in light drinking controls (CON); these measures largely normalized in ALC over 1 month of abstinence (Mon et al., 2012). MRS studies on the neurobiological effects of cocaine, amphetamines, alcohol or marijuana (i.e. mono-substance dependence) have revealed abnormal levels of NAA, Cr, Glu, choline-containing metabolites (Cho, marker of cell membrane turnover/synthesis), myo-Inositol (mI, osmoregulator and marker for astrogliosis) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Typically, these abnormalities were found in anterior frontal brain regions, temporal lobe, occipital gray matter (GM), parietal white matter (WM), thalamus, cerebellum and basal ganglia (for review see Licata and Renshaw, 2010). Mono-substance abuse/dependence is associated with neurocognitive dysfunction (Fernandez-Serrano et al., 2011), and recovery of initially abnormal brain metabolite levels during sustained abstinence from alcohol correlated with improvement in neurocognitive functioning (for review see Meyerhoff et al., 2011).

Although the literature on mono-substance abuse/dependence is expanding, cohorts are often not well characterized regarding substance use comorbidities. For example, alcohol use disorders (AUD) and the misuse of illicit drugs such as cocaine, marijuana and methamphetamine often co-occur (Stinson et al., 2005). In fact, individuals with AUD and comorbid abuse/dependence on additional substances (i.e. polysubstance abusers or PSU) represent the largest group of treatment-seeking individuals today (Medina et al., 2004; Kedia et al., 2007). While different drugs of abuse have been shown to alter neuronal integrity and neurotransmission via particular mechanisms (Licata and Renshaw, 2010; Riggio, 2011), their concurrent misuse may have synergistic or additive deleterious effects on neurobiology when compared with mono-substance abuse. Therefore, the detailed descriptions of neurobiological and neurocognitive alterations in well-characterized cohorts of PSU vs. ALC will contribute to the understanding of unique differences between these groups, which may foster a better appreciation of the potential need for specific pharmacological and/or behavioral interventions.

Few studies have investigated drug effects on brain metabolite concentrations in individuals dependent on more than one drug. One study demonstrated cerebral phosphorus metabolite level alterations in individuals dependent on cocaine, heroin and nicotine, suggesting glial cell proliferation and compromised energy metabolism in the first week of abstinence (Christensen et al., 1996). PSU actively abusing alcohol, heroin, cocaine, marijuana and other opiates had higher glucose metabolism rates in the fronto-temporal cortex than controls (Stapleton et al., 1995). Glucose metabolism, however, was lower in the right orbito-frontal cortex of 1-week-abstinent individuals abusing both methamphetamine and marijuana compared with methamphetamine abusers (Voytek et al., 2005). Also, currently using cocaine-dependent ALC showed lower frontal GABA levels than controls (Ke et al., 2004), whereas frontal cortical GABA concentration was not reduced in 1-week-abstinent individuals dependent on alcohol alone (Mon et al., 2012). Furthermore, our recent single-voxel 1H MRS in PSU at 1 month of abstinence (similar individuals as described here) showed lower NAA, Cho, Cr and mI concentrations in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex compared with 1-month-abstinent ALC, while metabolite levels in the anterior cingulate and parieto-occipital cortices were not significantly different (Abé et al., 2013), and metabolite levels in ALC after 1 month of abstinence were not different from control in any cortical region (Mon et al., 2012). The findings suggested persistent abnormalities in neuronal integrity, glial changes and possible edema in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of PSU, with lower GABA levels relating to greater cocaine consumption—not alcohol consumption—in the PSU group. Thus, PSU reveal a distinctly different metabolic profile than ALC after a similar duration of abstinence. Consistent with these neurobiological abnormalities, studies in PSU have also indicated deficient neurocognition compared with controls (Horner, 1997; Selby and Azrin, 1998; Verdejo-Garcia et al., 2004, 2007; Ersche et al., 2011; Laker, 2011). However, neurobiological characteristics of polysubstance use disorders and their associations with neurocognition require further elucidation.

To better understand neurometabolite alterations in abstinent PSU, we compared metabolite concentrations in 1-month-abstinent PSU, ALC and CON throughout the brain using metabolic imaging (1H MRSI). Absolute metabolite concentrations were quantified in GM and WM of the major lobes and in several subcortical brain regions. Although the study population was similar to that in our previous report (Abé et al., 2013), the regions examined and the experimental approaches were different and complementary, precluding direct comparisons. We also related neurocognitive function to our MRSI measures to determine the functional implications associated with chronic polysubstance use. Based on our earlier research and the substance abuse neuroimaging literature recently summarized (Licata and Renshaw, 2010), we hypothesized that PSU compared with ALC and CON demonstrate lower NAA and higher mI levels in the frontal and temporal lobes, thalamus and cerebellum, lower NAA in the lenticular nuclei and higher mI in the parietal lobe.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

All participants provided their written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki and underwent procedures approved by the University of California, San Francisco and the San Francisco VA Medical Center (SFVAMC). Treatment-seeking PSU (n = 18) and ALC (n = 36) were recruited from substance abuse treatment programs of the SFVAMC and Kaiser Permanente. All study participants were enrolled in either a residential or outpatient treatment program where they were tested daily for substance use. A positive test for any substance but nicotine excluded potential participants from enrollment in the study. All ALC and PSU participants met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. In addition, all but one PSU participants met DSM-IV criteria for dependence on at least one psychostimulant, with and without cannabis use disorder: cocaine (n = 13), cocaine plus marijuana (n = 1), methamphetamine (n = 1), cocaine plus methamphetamine plus marijuana (n = 1) and cocaine plus opiates (n = 1); one participant was dependent on opiates and benzodiazepines. Non-substance abusing individuals recruited from the local community were studied as controls (CON, n = 36); they had no history of biomedical and/or psychiatric conditions known to influence the study measures. Taking advantage of our large groups of ALC (n = 107) and CON (n = 61) studied with the same neuroimaging protocol, we first matched smaller groups on age, body mass index (BMI) and proportion of cigarette smokers to our PSU sample; we then randomly chose 36 ALC and CON from this subsample to assemble ALC and CON groups of twice the sample size of our PSU group. This group was a subsample (65%) of the PSU cohort that contributed to our previous 4 T single-voxel spectroscopy study (Abé et al., 2013). At the time of study, ALC and PSU were abstinent from alcohol and all substances other than tobacco for ∼1 month. Further inclusion and exclusion criteria are fully detailed elsewhere (Durazzo et al., 2004). Group demographics and relevant substance use characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, laboratory and substance consumption variables for ALC, PSU and CON (mean ± standard deviation)

| Variable | CON | ALC | PSU | P-value (CON vs. ALC) | P-value (CON vs. PSU) | P-value (ALC vs. PSU) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (male, female) | 36 (32, 4) | 36 (34, 2) | 18 (18,0) | – | – | – |

| Age (years) | 47.1 ± 8.6 | 46.7 ± 8.0 | 46.1 ± 9.5 | NS | NS | NS |

| Education (years) | 15.3 ± 2.2 | 13.9 ± 1.7 | 12.7 ± 1.3 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.033 |

| AMNART | 117.2 ± 6.4 | 114.7 ± 6.9 | 105.8 ± 8.5 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Lifetime years (alcohol) | 28.0 ± 9.8 | 29.6 ± 8.6 | 31.7 ± 9.4 | NS | NS | NS |

| Onset heavy drinking (age) | – | 23.7 ± 6.3 | 19.0 ± 3.6 | – | – | 0.006 |

| Months of heavy drinking | – | 232 ± 100 | 252 ± 140 | – | – | NS |

| Sober days | – | 31.9 ± 8.7 | 25.2 ± 11.9 | – | – | 0.022 |

| 1 year avg. (alcohol) (drinks/month) | 17 ± 17 | 403 ± 234 | 319 ± 351 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

| Lifetime avg. (alcohol) (Drinks/month) | 23 ± 14 | 217 ± 151 | 289 ± 309 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

| 1 year avg. (cocaine) (g/month) | – | – | 48 ± 43 | – | – | – |

| Lifetime avg. (cocaine) (g/month) | – | – | 43 ± 43 | – | – | – |

| Lifetime years (cocaine) | – | – | 24 ± 9 | |||

| FTND total (# of smokers) | 5.0 ± 1.4 (24) | 5.2 ± 2.2 (24) | 3.5 ± 1.7 (12) | NS | 0.023 | 0.010 |

| Cigarettes/day | 20.2 ± 6.7 | 19.9 ± 11.8 | 8.3 ± 6.9 | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 26.2 ± 3.8 | 26.3 ± 3.8 | 27.8 ± 4.6 | NS | NS | NS |

| Prealbumin (mg/dl) | 29.4 ± 5.5 | 26.7 ± 5.9 | 31.4 ± 7.5 | NS | NS | 0.031 |

| GGT (U/l) | 44.9 ± 74.2 | 45.7 ± 55.1 | 47.7 ± 88.9 | NS | NS | NS |

| Albumin (mg/dl) | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | NS | NS | NS |

| AST (U/l) | 46.3 ± 78.9 | 28.7 ± 9.6 | 46.4 ± 76.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| ALT (U/l) | 50.2 ± 89.0 | 34.3 ± 17.7 | 42.9 ± 59.1 | NS | NS | NS |

| WBC (K/mm3) | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 7.1 ± 2.2 | 5.7 ± 1.2 | NS | NS | 0.022 |

| RBC (M/mm3) | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | NS | NS | NS |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 15.0 ± 0.8 | 14.5 ± 0.9 | 14.6 ± 0.9 | NS | NS | NS |

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.2 ± 2.2 | 42.1 ± 2.6 | 43.1 ± 3.1 | NS | NS | NS |

| MCV (fl) | 89.7 ± 5.0 | 92.4 ± 3.8 | 92.8 ± 4.7 | NS | NS | NS |

| BDI | 4.5 ± 4.2 | 10.9 ± 6.3 | 11.8 ± 8.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

| State t anxiety y2 | 32.4 ± 6.7 | 44.1 ± 10.8 | 43.1 ± 11.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

| State t anxiety y1 | 26.5 ± 4.6 | 36.6 ± 10.3 | 34.0 ± 12.0 | <0.001 | 0.010 | NS |

NS, not significant (P > 0.05); FTND, Fagerstrom Tolerance Test for Nicotine Dependence; BMI, body mass index; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; WBC, white blood cell counts; RBC, red blood cell counts. State t anxiety y2, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Y-2; State t anxiety y1, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Y-1

Clinical assessment

ALC and PSU participants completed the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorder Patient Edition, Version 2.0 (First et al., 1998), and CON participants were administered the accompanying screening module. Within 1 day of the MR study, all participants completed questionnaires that assessed depression (Beck Depression Inventory; (Beck, 1978)) and anxiety symptomatologies (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Y-2; (Spielberger et al., 1977)). Alcohol consumption was assessed with the lifetime drinking history (Skinner and Sheu, 1982; Sobell et al., 1988; Sobell and Sobell, 1990), which yielded estimates of the average number of alcoholic drinks consumed per month over 1 year and 3 years before enrollment and over their lifetime. For PSU, lifetime substance use history (other than alcohol) was assessed with an in-house interview questionnaire based on the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992), NIDA Addictive Drug Survey (Smith, 1991), lifetime drinking history and Axis I disorders Patient Edition, Version 2.0 (SCID-I/P) (First et al., 1998). From this questionnaire, monthly averages for grams of cocaine and/or methamphetamine over 1 year prior to enrollment and over their lifetime were estimated (Abé et al., 2013). Level of nicotine dependence was assessed via the Fagerstrom Tolerance Test for Nicotine Dependence (Fagerstrom et al., 1991), and the total number of years of smoking over their lifetime was calculated. To evaluate basic nutritional, erythrocyte status and hepatocellular injury, we obtained laboratory tests as listed in Table 1 (blood measures not available in smoking CON).

Neurocognitive assessment

Within 3 days of the MR study, all participants completed a neurocognitive battery focusing on working memory (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) Digit Span), processing speed (WAIS-III Digit Symbol Coding, Symbol Search (Wechsler, 1997)), visuospatial learning and memory (Brief Visual memory Test-Revised, BVMT-R, total recall (learning) and delayed recall (memory) (Benedict, 1997)), as well as auditory-verbal learning and memory (California Verbal Learning Test-II, CVLT-II: immediate recall trials 1–5 (learning), short- and long-delayed free recall (memory) (Delis et al., 2000)); for details see Durazzo et al. (2007). Premorbid verbal intelligence was assessed using the American National Adult Reading Test (AMNART) (Grober and Sliwinski, 1991). Group comparisons on these measures will be presented in a separate report. Here, neurocognitive measures were used to investigate the functional relevance of the measured metabolite concentrations.

MR acquisition and processing

Participants were scanned on a Siemens Vision at 1.5 Tesla (Siemens Medical Systems, Inc., Iselin, NJ, USA). Structural MRI used a double spin-echo (DSE) sequence with TR/TE1/TE2 (repetition and echo times) = 5000/20/80 ms, 1 × 1 mm2 in-plane resolution and 48 contiguous 3-mm-thick axial slices oriented along an imaginary line connecting the anterior and posterior commissures as observed on mid-sagittal scout MRI. A volumetric magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequence (MPRAGE, TR/TE/TI = 9.7/4/300 ms, 15° flip angle, 1 × 1 mm2 in-plane resolution) yielded 1.5-mm thick coronal partitions oriented perpendicular to the long axes of bilateral hippocampi as seen on sagittal scout MRI. The MPRAGE images were segmented into WM, GM and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Van Leemput et al., 1999) and the following ROIs identified with an atlas-based method: frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital GM and WM; thalamus and lenticular nucleus; midbrain and cerebellar vermis. Further details can be found in Cardenas et al. (2005). The MRSI acquisition, processing and quality assurance methods are detailed in Meyerhoff et al. (2004). In short, MRI was followed by a multislice 1H MRSI sequence with TR/TI/TE = 1800/165/25 ms, imaging metabolites in three slices, each 15 mm thick with a slice gap of at least 6 mm, with an in-plane resolution of 8 × 8 mm2 (yielding a 1-ml nominal SI voxel; effective resolution of 1.5 ml). The SI slices were angulated parallel to the double spin echo slices, covering the major cerebral lobes, subcortical nuclei, midbrain and cerebellar vermis. Data processing and spectral fitting were performed offline to obtain absolute metabolite levels for each SI voxel expressed in institutional units (i.u.), herein referred to as concentrations. These voxel-specific metabolite concentrations were then averaged over all voxels contributing to a given region (e.g. frontal GM). We averaged metabolite concentrations obtained for ROIs from left and right hemispheres, because no significant side differences in metabolite concentrations were observed in any group. ROIs from individuals were only included in analyses when they yielded spectroscopic voxel counts greater than one-tenth of the respective mean voxel counts across groups; this minimum voxel count corresponded usually to a value about two standard deviations below the group mean. Individuals with voxel counts below two standard deviations of the mean for a specific ROI were eliminated from analyses. This approach resulted in average voxel counts ranging from 18 in the midbrain to 126 in frontal GM.

ALC and CON were scanned fully contemporaneously, while PSU were scanned contemporaneously and in random order with half of the ALC and CON cohorts. Data processing and quality checks were performed by operators blind to participant diagnosis.

Statistical analyses

Separate univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), covarying for age and BMI, were performed for metabolites in each ROI. The BMI was negatively correlated with MRS metabolite levels (Gazdzinski et al., 2008, 2010), and weak correlations were also found for several metabolites in the sample investigated here. Additional ANOVA was conducted without including age and BMI as covariates, and statistical outcomes did not differ. Multivariate analysis was not conducted because the number of participants varied across ROIs (between 81 and 90) and metabolites because of data quality. Significant ANCOVAs (P ≤ 0.05) or trends (P ≤ 0.1) were followed up by pairwise comparisons, to test for hypothesized group differences among PSU, ALC and CON in metabolite concentrations. In pairwise group comparisons of metabolite levels, alpha levels (0.05) were adjusted for the multiplicity of tests via a modified Bonferroni procedure (Sankoh et al., 1997). This approach yields adjusted alpha levels for each ROI separately based on the number of pairwise comparisons (three), metabolites measured (four) and their average intercorrelation among the four metabolites. The corresponding adjusted alpha levels for pairwise group comparisons ranged between 0.010 ≤ P ≤ 0.019. Effect sizes were calculated via Cohen's d (Cohen, 1988). Univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to test for differences in participant characteristics.

For each ROI within PSU, correlations (Spearman's Rho) of metabolite concentrations with neurocognitive measures (raw scores), days of abstinence and average monthly cocaine consumption quantities were calculated. Relationships between metabolite levels and neurocognitive tests were corrected for age (partial correlation coefficients reported). In these exploratory analyses, we did not correct for multiple comparisons and P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants’ characterization

Characteristics for ALC, PSU and CON are shown in Table 1. All three groups were equivalent on age. PSU had lower AMNART scores than ALC or CON. PSU and ALC had fewer years of education than CON, and PSU had less education than ALC. Although PSU had a higher prealbumin concentration than ALC and CON, and ALC had higher white blood cell counts than PSU and CON, these and other clinical laboratory measures were within the normal range for all groups. PSU and ALC did not differ on any quantitative alcohol consumption measure, but PSU were significantly younger (4.7 years) when they began drinking heavily. ALC were abstinent from alcohol for about 32 days at the time of study, whereas PSU were abstinent from both alcohol and illicit drugs for about 26 days. PSU and ALC were equivalent on measures of depressive and anxiety symptomatologies, and both groups had higher scores than CON. Among smokers, the Fagerstrom Tolerance Test indicated moderate nicotine dependence in PSU and moderate to high dependence in ALC and CON; PSU smoked significantly fewer cigarettes per day than ALC and CON. The ALC (and PSU) group contained two (one) participants diagnosed with hepatitis C and eight (four) with medically controlled hypertension. Excluding those cases from the analysis did not appreciably change the observed group differences. Furthermore, no group differences were observed for average tissue fractions in a ROI or number of voxels representing the ROIs.

The number of voxels making up GM regions ranged from 48 (occipital GM) to 126 (frontal GM), with average GM tissue fractions of 0.57–0.61. The average WM region voxel counts were between 26 (parietal WM) and 67 (frontal WM) with average WM tissue fractions of 0.60–0.90. Average voxel count for the midbrain was 18, 89 for the cerebellar vermis, 32 for the thalamus and 20 for the lenticular nucleus with average GM tissue fractions of 0.46–0.78 across these ROIs.

Group comparison of metabolite concentrations

Univariate tests (ANCOVA) were significant for mI concentration in the temporal GM (F(2,85) = 6.28, P = 0.003); they showed trends to significance for mI in the cerebellar vermis (F(2,80) = 2.97, P = 0.057) and the lenticular nucleus (F(2,83) = 3.99, P = 0.022) and for NAA in the midbrain (F(2,76) = 2.42, P = 0.096). In planned pairwise group comparisons (see Table 2) of metabolite levels in the temporal GM, PSU had significantly higher mI concentrations than both ALC and CON. PSU also had higher mI concentrations than CON in the cerebellar vermis and lenticular nucleus. In those regions, mI levels in PSU tended to be higher than in ALC. NAA concentration in the midbrain tended to be lower in PSU than CON, whereas occipital WM mI tended to be higher (both P < 0.05, but not significant after correction for multiple comparisons). Statistically significant group differences showed strong effect sizes, whereas the observed statistical trends corresponded to mean differences of moderate effect size. ALC and CON showed no significant differences in metabolite levels in any ROI. No other significant regional differences between ALC, PSU and CON were apparent; specifically, there were no significant lobar NAA differences.

Table 2.

Metabolite concentrations (institutional units, mean ± standard deviation) of PSU, ALC and CON: P-values of pairwise group comparisons and corresponding effect sizes (in parenthesis)

| Region and metabolite | CON | ALC | PSU | CON vs. ALC | CON vs. PSU | ALC vs. PSU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occipital WM mI | 16.7 ± 2.5 | 17.2 ± 2.5 | 18.2 ± 2.5 | NS (0.19) | 0.05 (0.59) | NS (0.42) |

| Temporal GM mI | 18.9 ± 2.9 | 18.8 ± 2.9 | 21.5 ± 2.9 | NS (0.08) | 0.003 (0.87) | 0.001 (0.94) |

| Cerebellar vermis mI | 22.8 ± 3.6 | 23.5 ± 3.6 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | NS (0.18) | 0.017 (0.76) | 0.069 (0.58) |

| Lenticular nucleus mI | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 15.8 ± 2.8 | 17.4 ± 2.8 | NS (0.31) | 0.006 (0.87) | 0.073 (0.56) |

| Midbrain NAA | 34.1 ± 5.1 | 32.3 ± 5.2 | 30.5 ± 5.2 | NS (0.35) | 0.035 (0.68) | NS (0.33) |

Adjusted alpha levels: P = 0.013 (temporal GM), P = 0.017 (occipital WM), P = 0.015 (midbrain), P = 0.019 (verebellar vermis), P = 0.012 (lenticular nuclei). Comparisons significant after correction for multiple comparisons are bolded. Only significant or trend-level findings (P < 0.1) are shown.

Although GM tissue contribution did not differ significantly between groups in any ROI, in exploratory analysis we covaried for it in exploratory three-group comparisons [for effects of GM/WM/CSF tissue contributions on metabolite concentrations see Jansen et al. (2006)]; GM-tissue contribution was not a significant predictor of metabolite concentrations in any ROI in ANCOVAs comparing ALC, PSU and CON. The same applied for smoking status (non-smoker and smoker), years of education and AMNART. Similarly, depression and anxiety symptomatologies, days of sobriety, onset of heavy drinking and any drinking severity measure did not significantly predict metabolite concentration differences between PSU and ALC.

Correlations among main outcome measures

Metabolite concentrations and neurocognition

In PSU, higher frontal GM NAA and frontal WM Cr were related to higher scores on Digit Symbol Coding and Symbol Search (measures of processing speed) (see Table 3). Higher lenticular nucleus Cr and Cho correlated with better performance on WAIS-III Digit Span (working memory). Lower occipital GM mI was related to better scores on BVMT-R Total Recall (visuospatial learning) and Delayed Recall (visuospatial memory), and higher parietal WM Cr was associated with better performance on CVLT-II Immediate Recall (auditory-verbal learning). Higher temporal WM mI was related to better scores on BVMT Delayed Recall, and lower thalamus Cr correlated with better scores on Digit Symbol Coding.

Table 3.

Significant (P ≤ 0.05) age-corrected partial correlations r* > 0.3 between brain metabolite concentrations and neurocognitive test measures within PSU (bold), ALC (italic) and CON (normal font). When the groups showed correlations of similar significance, strength and direction between the same measures, we report the correlations of the combined groups and indicate the group(s) by superscript(s)

| Regional metabolite | CVLT-II: immediate recall | CVLT-II: short delayed free recall | BVMT-R: total recall | BVMT-R: delayed recall | WAIS-III: digit span | WAIS-III: digit symbol coding | WAIS-III: symbol search |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal GM NAA | – | – | 0.45 | 0.36 | – | 0.36a,b | – |

| Frontal WM NAA | – | – | – | – | – | 0.40 | – |

| Frontal WM Cr | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.59 |

| Parietal GM NAA | −0.38 | – | 0.37 | – | – | ||

| Parietal GM Cho | – | – | – | 0.39 | – | – | |

| Parietal GM mI | −0.44 | −0.36 | – | −0.42 | – | – | |

| Parietal WM NAA | – | – | – | 0.48 | – | – | – |

| Parietal WM Cho | – | – | – | 0.36 | – | – | – |

| Parietal WM Cr | 0.64 | – | −0.41 | 0.47 | – | – | – |

| Temporal GM Cho | −0.38 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Temporal WM mI | −0.43 | −0.40 | – | 0.61 | – | – | 0.36 |

| Occipital GM mI | – | – | −0.37a | −0.42a | – | – | – |

| Cerebellar vermis Cr | – | – | 0.42 | – | −0.37 | – | – |

| Midbrain NAA | – | – | 0.38 | – | – | – | – |

| Thalamic Cho | −0.44 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Thalamic Cr | – | – | – | – | – | −0.54 | |

| Thalamic mI | −0.35b | −0.32b | −0.52 | – | −0.38b | – | – |

| Lenticular NAA | – | – | 0.52 | 0.41 | – | 0.43 | 0.36 |

| Lenticular Cho | −0.47 | – | – | 0.37 | 0.76 | – | – |

| Lenticular Cr | – | – | – | – | 0.69 | – | – |

| Lenticular mI | −0.36 | – | −0.38 | – | – | – | – |

aCorrelation with similar correlation coefficient and significance also in ALC.

bCorrelation with similar correlation coefficient and significance also in CON.

In all groups, higher frontal GM NAA correlated with better performance on WAIS-III: Digit Symbol Coding, a measure of processing speed. Otherwise, the pattern of correlations in PSU was different from those observed in ALC and CON, who showed more similar correlation patterns. Specifically, the PSU group was missing associations between regional NAA concentrations (except frontal GM NAA) and cognitive performance. In both ALC and CON, higher thalamic and lobar mI was associated with poorer performance on CVLT-II measures of auditory-verbal learning and memory) and on the WAIS-III: Digit Span measure of working memory. In LD, better neurocognitive measures were generally related to higher lenticular and frontal cortical NAA and to lower regional mI concentrations.

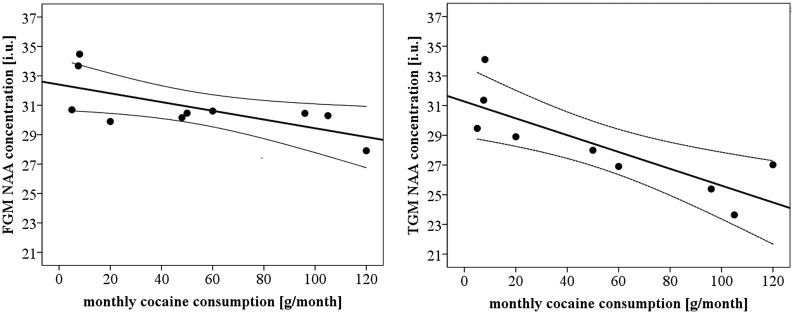

Metabolite levels and cocaine consumption within PSU

Within PSU and as depicted in Fig. 1, greater monthly cocaine consumption averaged over 1 year was associated with lower NAA in temporal GM (P = 0.007, r = −0.82; slope b = −0.06; n = 9) and frontal GM (P = 0.031, r = −0.68; slope: b = −0.03; n = 10), which also correlated with worse processing speed (see above). The observed correlations remained significant after controlling for 1-year average drinks/month.

Fig. 1.

Monthly cocaine consumption quantities in PSU vs. NAA concentration in frontal GM (FGM, left panel) and temporal GM (TGM, right panel). i.u. represents institutional units, for participants with both cocaine use and useful metabolite data. Regression fit and 95% confidence interval of the mean are indicated.

Metabolite levels and days of abstinence within PSU and ALC

Numerous strong correlations between regional metabolite concentrations and days of abstinence were found within PSU (see Table 4). Higher Cr concentrations in frontal and parietal GM and in frontal WM, as well as higher Cho levels in parietal GM were related to longer duration of abstinence. Unexpectedly, higher mI concentrations in frontal and parietal GM, parietal and temporal WM, as well as higher thalamic mI concentrations were associated with longer abstinence. Importantly, while ALC showed significant correlations between days of abstinence and higher NAA in frontal GM and WM (suggesting some recovery of metabolic abnormalities during abstinence), PSU did not show such relationships. We also calculated partial correlations between metabolite concentrations and days of abstinence in PSU controlling for age. All correlations reported in Table 4 remained significant, except the correlations between parietal GM Cho and temporal WM mI with days of abstinence. However, as days of abstinence are not related to age, the reported bivariate correlations are likely more appropriate.

Table 4.

Brain metabolite concentrations and days of abstinence within PSU: Spearman's correlations (rho) and statistical significance (P-values)

| Group | Region and metabolite | r, P-value |

|---|---|---|

| PSU | Frontal GM Cr | 0.67, 0.003 |

| Frontal GM mI | 0.71, 0.002 | |

| Frontal WM Cr | 0.55, 0.035 | |

| Parietal GM Cho | 0.57, 0.035 | |

| Parietal GM Cr | 0.90, 0.000 | |

| Parietal GM mI | 0.53, 0.053 | |

| Parietal WM mI | 0.62, 0.018 | |

| Temporal WM mI | 0.56, 0.029 | |

| Thalamus mI | 0.58, 0.016 | |

| ALC | Frontal GM NAA | 0.38, 0.023 |

| Frontal WM NAA | 0.49, 0.003 |

DISCUSSION

We compared absolute brain metabolite concentrations in GM and WM of the major lobes, as well as in subcortical brain regions (midbrain, thalamus, lenticular nucleus and cerebellar vermis) of PSU and ALC after 1 month of abstinence to CON. All groups were matched on age, BMI and smoking prevalence. PSU demonstrated significantly higher mI concentrations than CON in temporal GM, cerebellar vermis and lenticular nuclei. NAA in the midbrain tended to be lower in PSU than CON, and mI tended to be higher in the cerebellar vermis and lenticular nuclei of PSU vs. CON. Compared with ALC with similar abstinence duration, mI in temporal GM of PSU was significantly higher. Thus, our a priori hypotheses on elevated regional mI in PSU were largely confirmed, whereas our hypotheses of lower regional NAA were not. Metabolite levels in ALC and CON were statistically equivalent, presumably due to recovery of initially low metabolite levels with abstinence from alcohol (Durazzo et al., 2004; Mon et al., 2012). Moreover, cortical metabolite levels were significantly related to neurocognitive measures, affirming the functional relevance of absolute MRS measures (e.g. lower frontal GM NAA correlated with slower processing speed in all three groups). The patterns of these relationships were different between PSU, ALC and CON groups, suggesting that polysubstance use affects those relationships and/or that cognitive performance/tasks are supported via different mechanisms/pathways in the groups. Finally, lower NAA concentrations in temporal and frontal GM of PSU correlated uniquely to greater cocaine but not alcohol use quantities.

Although numerous MRS studies reported altered NAA, Cho, Cr and mI in anterior brain regions associated with mono-substance use disorders even after 30 days of abstinence (Licata and Renshaw, 2010), we did not find any significant differences of metabolite concentrations within large lobar frontal regions between CON and 1-month-abstinent PSU and ALC. This, together with our recent single-volume 1H MRS data in a similar PSU cohort (Abé et al., 2013), suggests that metabolic abnormalities in the frontal cortex of PSU are still present at this stage of recovery, but appear to be localized in functionally important subregions (e.g. dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) rather than across the entire frontal cortex. Furthermore, we found higher mI levels in PSU in several other brain regions compared with CON and 1-month-abstinent ALC. High mI is hypothesized to be the result of glial activation or gliosis, commonly interpreted as astroglial hypertrophy and/or proliferation, which, in turn, is often related to poorer neurocognition (Schweinsburg et al., 2001; Licata and Renshaw, 2010; Meyerhoff et al., 2011; Mon et al., 2012). It is also suggested that elevations of mI occur as a result of accumulating osmolites, which may reflect the effort of cells to regulate volume and help stabilize protein structures under osmolar stress (Schweinsburg et al., 2000). Thus, our results suggest that polydrug consumption is associated with astrocytosis/gliosis (consistent with findings from phosphorus MRS (Christensen et al., 1996)) and/or osmotic changes in temporal GM and subcortical regions, detectable at about 30 days of abstinence. Considering the SI voxel size of 1 ml and the average temporal GM tissue fraction of 0.61, it is difficult to determine if the elevation of mI in PSU was specific to temporal GM. However, as mI group differences are not seen in temporal WM tissue, these mI elevations appear restricted to the temporal cortex. In addition, and although we did not observe group differences of NAA in all cortical GM regions, the strong association between higher monthly cocaine consumption in PSU and lower cortical GM NAA supports our interpretation of some dose-related compromise of cortical neuronal integrity in PSU compared with both ALC and CON.

The comparison of PSU and CON suggests that cerebral abnormalities are also present in the cerebellar vermis and lenticular nucleus of PSU. One possible reason for the observed statistical trends for higher mI in these regions of PSU compared with ALC (moderate effect sizes) could be that cerebral abnormalities might be present in ALC, but to a weaker extent than in PSU. Our results also indicate that astroglial/astrocyte (higher mI) and neuronal integrity (lower NAA) are abnormal in the occipital WM and midbrain of PSU, respectively.

In PSU, the strong positive relationships between days sober and Cr (and Cho) measures in frontal and parietal GM are consistent with the short-term metabolic recovery we previously observed in ALC (Durazzo et al., 2006; Mon et al., 2012). However, higher mI levels in several brain regions (frontal GM, parietal GM, parietal WM and temporal WM) correlated to longer duration of abstinence and higher temporal WM mI correlated to better scores on BVMT Delayed Recall in the present study is surprising for the following reasons: elevated mI is usually associated with adverse brain function (see Table 3), and longer duration of abstinence is generally associated with neurobiological improvements. However, a possible explanation for observed positive relationships between mI levels and days of abstinence might be that lower mI is present in large lobar regions of PSU very early in recovery (e.g. in the first week, or even before abstinence) with reactive gliosis progressing during early abstinence. This would be similar to what was observed in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of 1-month-abstinent PSU (Abé et al., 2013). During prolonged abstinence (i.e. 10–45 days, as studied here) mI concentrations may increase, associated with cell volume changes, greater glial activation and accumulation of mI and/or gliosis, which then may be followed by a possible normalization of mI levels later in abstinence. But this is speculative and can only be tested in fine-grained longitudinal studies of long-term abstinent PSU. However, the positive correlations found for regional Cr and Cho levels with days of abstinence suggest that the observed increases in the mI level over time are paralleled by a metabolic recovery and neurobiologic improvements. Those improvements within PSU are further supported by the strong positive relationship between BVMT delayed recall and temporal WM mI concentration.

In sum, it appears that neurobiological abnormalities in 1-month-abstinent PSU are qualitatively and regionally different from those in ALC at 1 month of abstinence and/or might be longer lasting than in ALC. Many of other determining factors being equal in this study, it is likely that the observed metabolite group differences between PSU and ALC or CON are associated with the concurrent multiple drug use in PSU. In addition, the interaction of two or more different drugs used concurrently leads to formation of adducts of the primary substances used and their metabolites (e.g. cocaethylene, benzoylecgonine, norcocaine, norcocaethylene (Chen et al., 2012; Pfefferbaum et al., 2012)); these may have additional toxic and/or inflammatory effects on brain tissue (Stavro et al., 2013) above and beyond the effects of stimulants and/or alcohol alone.

Study limitations and outlook

Limitations of this cross-sectional study performed at 30 days of abstinence include the fact that we are unable to determine the nature and magnitude of metabolic abnormalities that likely exist in PSU very early in abstinence. Although the correlation between metabolite concentrations and days of abstinence within PSU supports our interpretation of cellular dysfunction associated with substance use, longitudinal follow-up will assist in clarifying if the observed abnormalities are reversible with extended abstinence, or if our observations are influenced by premorbid and/or comorbid factors not assessed in this study. Specifically, differences in personality (e.g. impulsivity, anger management), the earlier onset of heavy drinking in the PSU group (potentially reflecting greater interactions between adolescent brain development and alcohol exposure in the PSU group) and potential group differences in genetic predisposition/make-up may contribute to the observed metabolic differences. The present study had a relatively small sample size of PSU (n = 18) and future studies with enhanced power might allow for detection of further group differences and the exploration of distinct cigarette-smoking effects on brain metabolite levels. Future studies could also help clarify the degree to which the abnormal regional brain metabolite levels in PSU are related to relapse risk, as previously described in individuals with AUD (Durazzo et al., 2008; Durazzo et al., 2010).

CONCLUSIONS

MRSI-derived metabolite concentrations show that 1-month-abstinent PSU had persistent metabolic abnormalities (higher mI), primarily in the temporal cortex, cerebellar vermis and lenticular nucleus, when compared with ALC at 1 month of abstinence and CON. These abnormalities reflect cellular injury/dysfunction in PSU (astrocytosis/gliosis or osmotic changes). Furthermore, reduced neuronal integrity in temporal and frontal GM is related to cocaine use quantities, and some regional metabolite concentrations were related to neurocognition, highlighting the functional significance of these MRSI-determined metabolite levels. The results of this MRSI study complement our previous neurometabolic PSU characterization (Abé et al., 2013); together, they point to abnormalities in specific regional brain metabolite concentrations as polydrug abuse biomarkers and as potential targets for pharmacological and behavioral PSU-specific treatment.

Funding

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health (AA10788 (D.J.M.), DA025202 (D.J.M.) and DA24136 (T.C.D.)) and by the use of resources and facilities at the San Francisco Veterans Administration Medical Center and administered by the Northern California Institute for Research and Education. None of the authors report any associated financial interests in the research or any potential conflicts of interest.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Stefan Gazdzinski for his contribution to MR data acquisition; Diana Truran Sacrey for her assistance with some data processing tools; Mary Rebecca Young, Kathleen Altieri, Ricky Chen, and Drs Peter Banys and Ellen Herbst of the VA Substance Abuse Day Hospital, and Dr David Pating, Karen Moise and their colleagues at the Kaiser Permanente Chemical Dependency Recovery Program in San Francisco for their valuable assistance in recruiting participants. The authors thank all participants who volunteered for this study.

References

- Abé C, Mon A, Durazzo TC, et al. Polysubstance and alcohol dependence: unique abnormalities of magnetic resonance-derived brain metabolite levels. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression Inventory. Philadelphia: Center for Cognitive Therapy; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict R. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test—Revised: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Buhler M, Mann K. Alcohol and the human brain: a systematic review of different neuroimaging methods. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1771–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas VA, Studholme C, Meyerhoff DJ, et al. Chronic active heavy drinking and family history of problem drinking modulate regional brain tissue volumes. Psychiatry Res. 2005;138:115–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Walker J, Momenan R, et al. Relationship between liver function and brain shrinkage in patients with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:625–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen JD, Kaufman MJ, Levin JM, et al. Abnormal cerebral metabolism in polydrug abusers during early withdrawal: a 31P MR spectroscopy study. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:658–63. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, et al. California Verbal Learning Test. 2nd edn. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Banys P, et al. Cigarette smoking exacerbates chronic alcohol-induced brain damage: a preliminary metabolite imaging study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1849–60. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000148112.92525.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Meyerhoff DJ. Neurobiological and neurocognitive effects of chronic cigarette smoking and alcoholism. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4079–100. doi: 10.2741/2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Banys P, et al. Brain metabolite concentrations and neurocognition during short-term recovery from alcohol dependence: preliminary evidence of the effects of concurrent chronic cigarette smoking. Alc Clin Exp Research. 2006;30:539–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Gazdzinski S, Yeh PH, et al. Combined neuroimaging, neurocognitive and psychiatric factors to predict alcohol consumption following treatment for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:683–91. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Rothlind JC, Gazdzinski S, et al. Chronic smoking is associated with differential neurocognitive recovery in abstinent alcoholic patients: a preliminary investigation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1114–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durazzo TC, Pathak V, Gazdzinski S, et al. Metabolite levels in the brain reward pathway discriminate those who remain abstinent from those who resume hazardous alcohol consumption after treatment for alcohol dependence. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2010;71:278–89. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Barnes A, Jones PS, et al. Abnormal structure of frontostriatal brain systems is associated with aspects of impulsivity and compulsivity in cocaine dependence. Brain. 2011;134:2013–24. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrom KO, Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT. Nicotine addiction and its assessment. Ear Nose Throat J. 1991;69:763–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Serrano MJ, Perez-Garcia M, Verdejo-Garcia A. What are the specific vs. generalized effects of drugs of abuse on neuropsychological performance? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:377–406. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0, 8/98 revision) New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzinski S, Kornak J, Weiner MW, et al. Body mass index and magnetic resonance markers of brain integrity in adults. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:652–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.21377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdzinski S, Millin R, Kaiser LG, et al. BMI and neuronal integrity in healthy, cognitively normal elderly: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:743–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13:933–49. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner MD. Cognitive functioning in alcoholic patients with and without cocaine dependence. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1997;12:667–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen JF, Backes WH, Nicolay K, et al. 1H MR spectroscopy of the brain: absolute quantification of metabolites. Radiology. 2006;240:318–32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2402050314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Y, Streeter CC, Nassar LE, et al. Frontal lobe GABA levels in cocaine dependence: a two-dimensional, J-resolved magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Psychiatry Res. 2004;130:283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedia S, Sell MA, Relyea G. Mono- versus polydrug abuse patterns among publicly funded clients. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laker SR. Epidemiology of concussion and mild traumatic brain injury. PM R. 2011;3:S354–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Renshaw PF. Neurochemistry of drug action: insights from proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging and their relevance to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:148–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina KL, Shear PK, Schafer J, et al. Cognitive functioning and length of abstinence in polysubstance dependent men. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19:245–58. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00043-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff D, Blumenfeld R, Truran D, et al. Effects of heavy drinking, binge drinking, and family history of alcoholism on regional brain metabolites. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:650–61. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000121805.12350.CA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff DJ, Durazzo TC, Ende G. Chronic alcohol consumption, abstinence and relapse: brain proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in animals and humans. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2011;13:511–40. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mon A, Durazzo T, Meyerhoff DJ. Glutamate, GABA, and other cortical metabolite concentrations during early abstinence from alcohol and their associations with neurocognitive changes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Rohlfing T, Rosenbloom MJ, et al. Combining atlas-based parcellation of regional brain data acquired across scanners at 1.5 T and 3.0 T field strengths. Neuroimage. 2012;60:940–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggio S. Traumatic brain injury and its neurobehavioral sequelae. Neurol Clin. 2011;29:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2010.10.008. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankoh AJ, Huque MF, Dubey SD. Some comments on frequently used multiple endpoint adjustment methods in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1997;16:2529–42. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971130)16:22<2529::aid-sim692>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg BC, Taylor MJ, Videen JS, et al. Elevated myo-inositol in gray matter of recently detoxified but not long-term alcoholics: a preliminary MR spectroscopy study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:699–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinsburg BC, Taylor MJ, Alhassoon OM, et al. Chemical pathology in brain white matter of recently detoxified alcoholics: a 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy investigation of alcohol-associated frontal lobe injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:924–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby MJ, Azrin RL. Neuropsychological functioning in drug abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43:1157–70. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS. Addictive Drug Survey Manual. Baltimore, MD: NIDA Addiction Research Center; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Self-reports issues in alcohol abuse: state of the art and future directions. Behav Assess. 1990;12:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Riley DM, et al. The reliability of alcohol abusers’ self-reports of drinking and life events that occurred in the distant past. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49:225–32. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, et al. Self-Evaluation Questionaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton JM, Morgan MJ, Phillips RL, et al. Cerebral glucose utilization in polysubstance abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;13:21–31. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00132-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavro K, Pelletier J, Potvin S. Widespread and sustained cognitive deficits in alcoholism: a meta-analysis. Addict Biol. 2013;18:203–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dawson DA, et al. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:105–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A. 2000. Brain Vulnerability to Alcoholism: Evidence from Neuroimaging studies NIAAA.

- Van Leemput K, Maes F, Vandermeulen D, et al. Automated model-based tissue classification of MR images of the brain. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 1999;18:897–908. doi: 10.1109/42.811270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Lopez-Torrecillas F, Gimenez CO, et al. Clinical implications and methodological challenges in the study of the neuropsychological correlates of cannabis, stimulant, and opioid abuse. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14:1–41. doi: 10.1023/b:nerv.0000026647.71528.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-Garcia A, Rivas-Perez C, Vilar-Lopez R, et al. Strategic self-regulation, decision-making and emotion processing in poly-substance abusers in their first year of abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytek B, Berman SM, Hassid BD, et al. Differences in regional brain metabolism associated with marijuana abuse in methamphetamine abusers. Synapse. 2005;57:113–5. doi: 10.1002/syn.20155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale—III (WMS—III) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]