Abstract

Examination of three frozen bodies, a 13-y-old girl and a girl and boy aged 4 to 5 y, separately entombed near the Andean summit of Volcán Llullaillaco, Argentina, sheds new light on human sacrifice as a central part of the Imperial Inca capacocha rite, described by chroniclers writing after the Spanish conquest. The high-resolution diachronic data presented here, obtained directly from scalp hair, implies escalating coca and alcohol ingestion in the lead-up to death. These data, combined with archaeological and radiological evidence, deepen our understanding of the circumstances and context of final placement on the mountain top. We argue that the individuals were treated differently according to their age, status, and ritual role. Finally, we relate our findings to questions of consent, coercion, and/or compliance, and the controversial issues of ideological justification and strategies of social control and political legitimation pursued by the expansionist Inca state before European contact.

Keywords: bioarchaeology, computed tomography, Erythroxylum coca, ice mummies, South America

The three bodies discovered separately entombed within a shrine near the summit of 6,739-m Volcán Llullaillaco in northwest Argentina (latitude, 24° 43′ 17″ S; longitude, 68° 32′ 15″ W) in 1999 make up arguably the best naturally preserved assemblage of mummies found anywhere in the world (1). Here we use biochemical, radiological, and archaeological methods to explore the Inca practice of child sacrifice known as capacocha. We address questions concerning the temporal sequence that concluded with death and elucidate some of the practices associated with a complex rite. We use incremental liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) data from scalp hair to show changing patterns of coca and alcohol use for each individual, and segmented CT data coupled with archaeological observations to examine in detail the final hours of the eldest individual and the circumstances of her placement within the mountain-top shrine.

Although the term “child sacrifice” has often been used as a descriptor for these individuals in Andean archaeology and popular writing, we are cognizant of the fact that identity and status are complex questions with respect to biological age (discussed further in the context of our bioarchaeological data). We also recognize that the killing of humans within a ritualized framework took many forms within Andean South America (2), and that a range of perceptions of intentionality, agency, and phenomenological understandings of “life” and “death” exist, and existed. Terminologies necessarily entail tacit, and sometimes explicit, moral judgments (for example, in the alternative terms “victim” and “offering”), which are in themselves problematic in cross-cultural analysis. What we can be clear of here is that the three individuals, children in our terms (although the 13-y-old may have been perceived as belonging to a different age grade than the two younger ones), did not die accidentally, and that their deaths were commissioned as a central, and probably defining, element of a capacocha ritual. We also recognize that the capacocha rite analyzed here was embedded within a multidimensional imperial ideology.

The frozen remains of the ∼13-y-old “Llullaillaco Maiden,” the 4- to 5-y-old “Llullaillaco Boy,” and the 4- to 5-y-old “Lightning Girl” provide unusual and valuable analytical opportunities. Their posture and placement within the shrine, surrounded by elite artifacts, in tandem with sensitive postmortem assessment, allows unique insight into the form and duration of Inca rites. A principal justification for the original excavation and removal of these natural mummies following their discovery was the strong possibility of illegal looting (as documented at similar sites) and the impossibility of providing adequate in situ protection. Nevertheless, given the remarkable state of bodily preservation, it is also clear that any analytical examination must involve the application of noninvasive or minimally destructive scientific techniques. Previous biomolecular research has focused on the health (3), genetic origins, and nutritional status of these children. Segmental analysis of their hair (4) provides detailed information about status changes (in terms of quality of diet) through the use of carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis, and—via changes in sulfur and oxygen isotopes—about locational/altitudinal changes that indicate likely durations of ritual journeys and possible ceremonial routes. The Maiden’s long, tightly braided hair provided a 2-y antemortem timeline [based on average hair growth of 1 cm/mo (5)]; in this case, cross-matching of DNA and isotope data between bagged hair found with the children and hair sampled directly from the scalp provided insight into the phasing of hair treatment (cutting, dressing, and trimming) congruent with dietary changes. Together, these indicate the passage of the Maiden through a series of ritual stages, beginning with her status elevation (marked by dramatic dietary change) 1 y before death. Although cranial trauma and perimortem vomiting have been documented in the case of other capacocha victims, such as the children found on Ampato, Sara Sara, Aconcagua, and Picchu Picchu (6, 7), the apparent absence of evidence for direct violence at Llullaillaco suggests that deaths here may have been accomplished in some other way(s).

An understanding of ritualized activity sequences for these children can be significantly enhanced by considering diachronic data on alcohol and coca markers preserved in their sampled hair: cocaine (COC), the major alkaloid in coca leaves; benzoylecgonine (BZE), the major metabolite of COC; and cocaethylene (COCE), a metabolite formed in the presence of alcohol. We also use archaeology and CT/radiology to examine in detail the perimortem activity that culminated in the deliberate installation of the Maiden and the other two children in three chambers within a stone-built ceremonial platform constructed 25 m below the 6,739-m frozen summit of Llullaillaco. These chambers were constructed by making use of natural niches in the bedrock, the children seated at depths ranging from 1.2 to 2.2 m below the surface (1). The Llullaillaco Boy was uncovered in the southwest burial, the Lightning Girl in the east burial, and the Maiden in the north burial. The extensive artifact assemblage included wooden drinking vessels (keros), ceramics (e.g., aribalos for liquids), and richly decorated textile bags (e.g., chuspas for coca) that retained their more ephemeral foodstuff contents—offerings including maize, peanuts, and coca leaves—with dried camelid meat also found within the burials. Coca use, established from bulk hair analyses (4), is evidenced right until the point of death by a preserved coca quid still clenched between the Maiden’s teeth; here we look at this evidence in greater detail, establishing major changes in coca consumption with concurrent alcohol use that occurred in the final weeks of this individual’s life. Our evidence for significant dietary and status changes connected with diachronic ritual sequences (4) raises further questions about the basis for these changing levels of coca ingestion and alcohol consumption by the children in the months leading up to their deaths—principally whether, in the final weeks, the consistently higher levels of COC and alcohol found in the Maiden’s hair, compared with the younger children, may suggest a greater need to sedate her.

Results

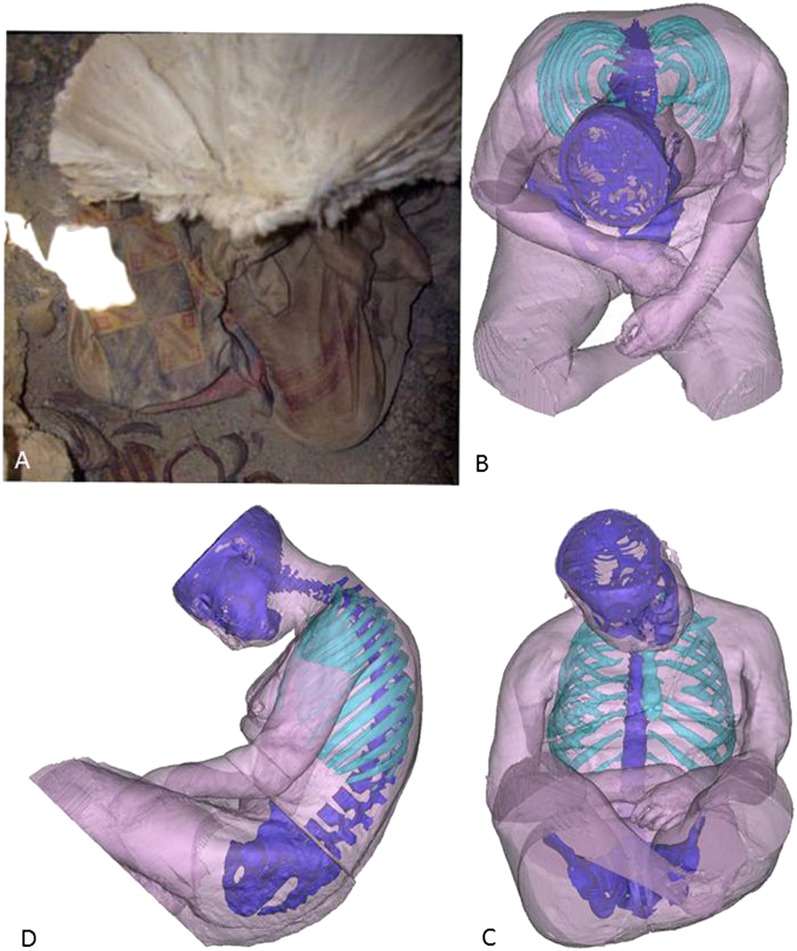

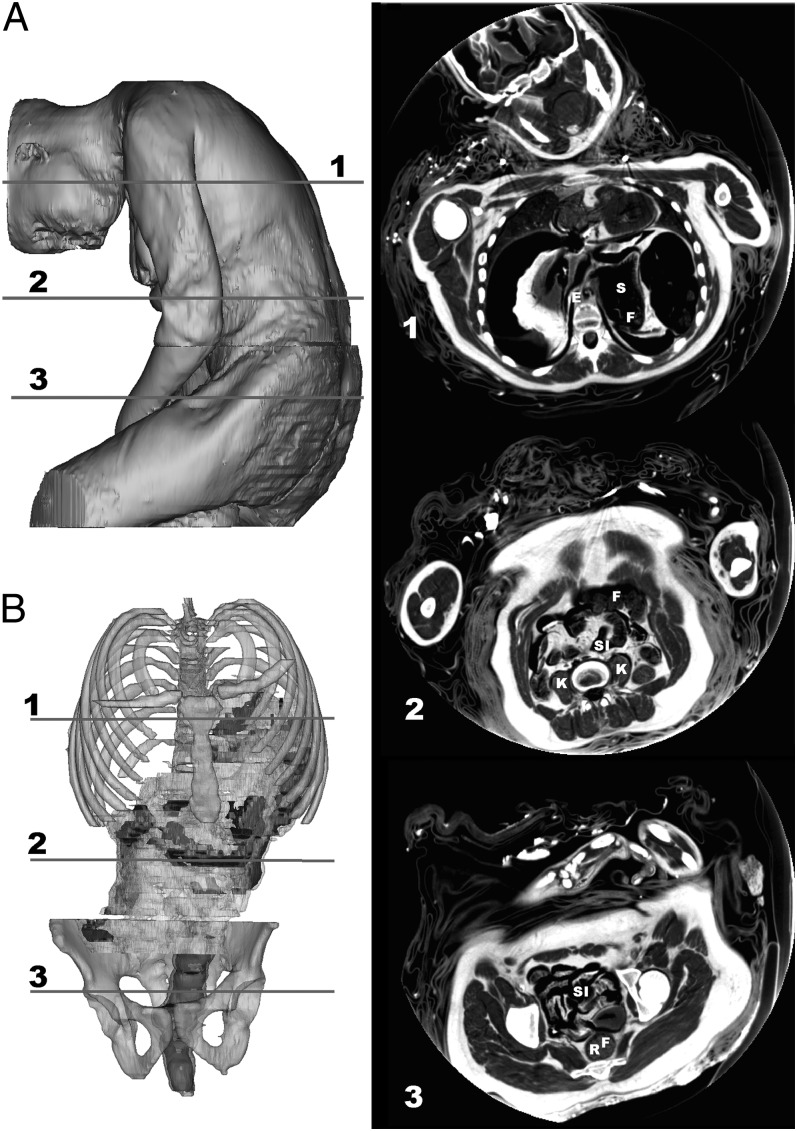

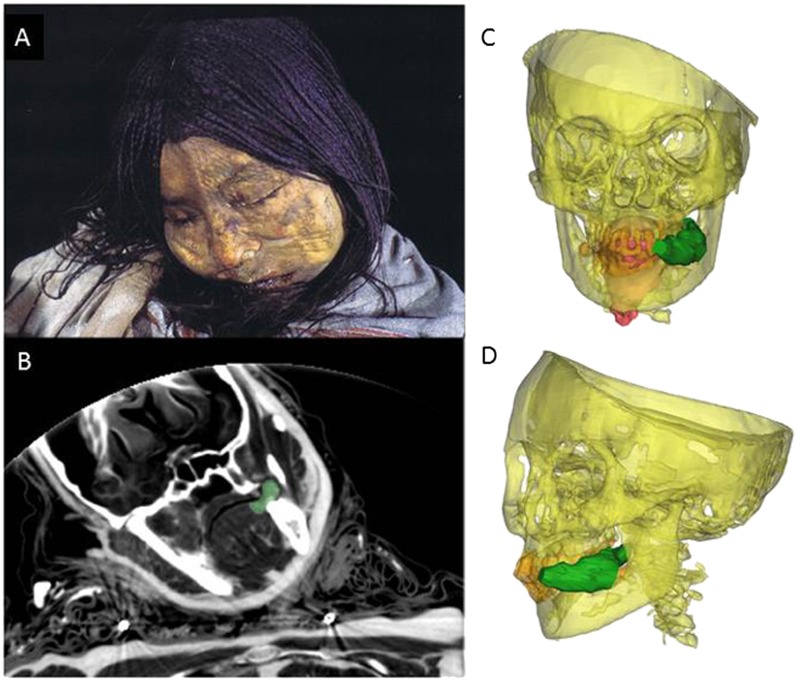

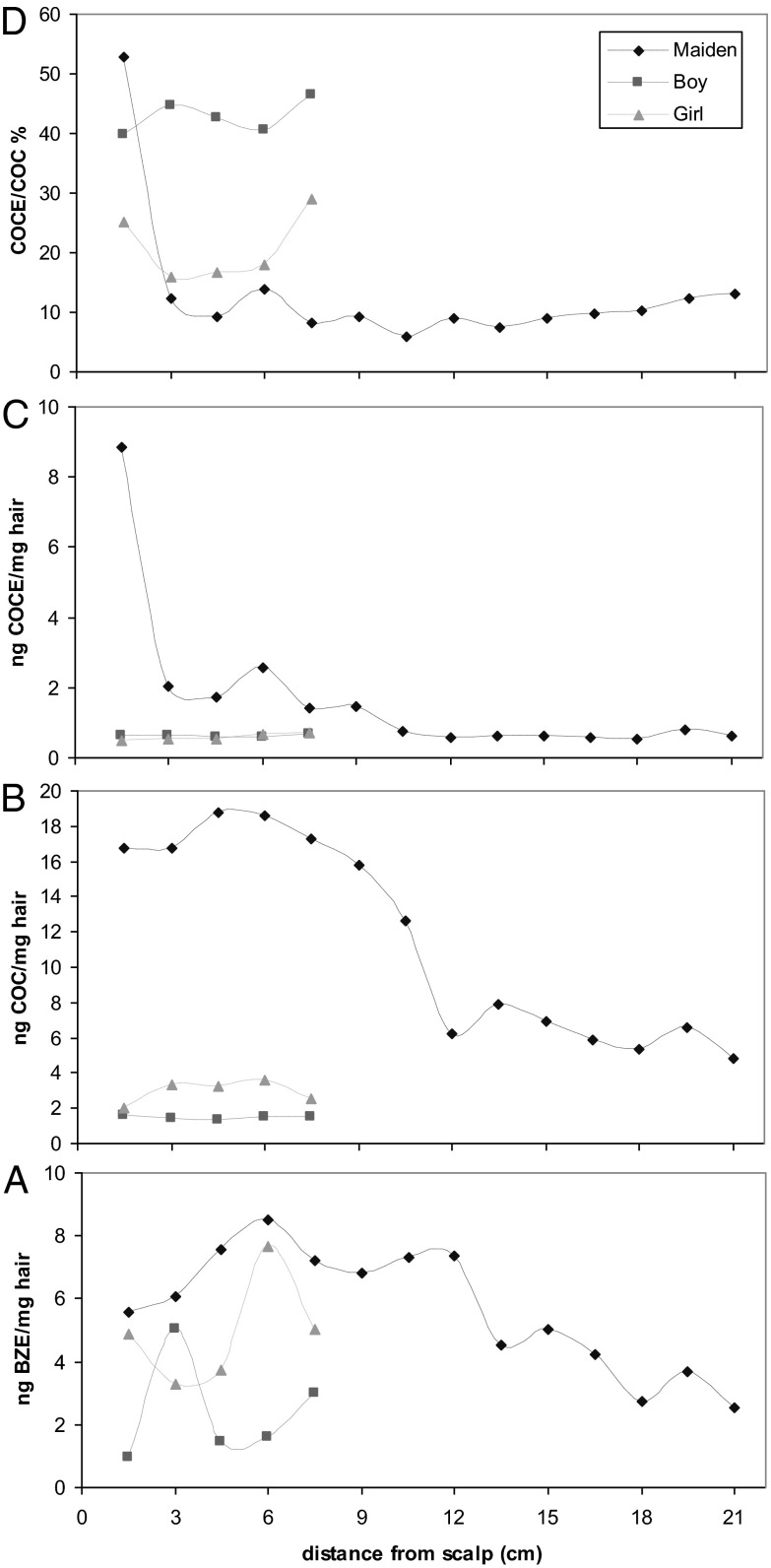

The ordered juxtaposition of the children, their clothing, adornments, and offerings, is highlighted by the Maiden, for whom detailed postural evidence provided by segmented CT-scan data shows that she was seated cross-legged, with her head slumped forward and her arms resting loosely on her lap (Fig. 1). Significantly, the array of plates and ceramic vessels laid at her feet within the burial survived upright and undisturbed, as did the feather headdress she was wearing, placed on top of the dark brown textile that covered her entire head (Fig. 2). This evidence suggests that she was placed there while heavily sedated, her position carefully arranged and the artifacts placed around her. A summary catalogue of associated finds is provided in Table S1. The radiological evidence for the Maiden shows her intact organs, food within the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 3), and a coca quid held between her teeth (Fig. 4). The size of this quid is approximately 44 × 11 mm (buccal portion), with 26 × 12 mm (lingual portion) within the mouth. The radiological data also show clear evidence of consistent preservation conditions for all three children, offering assurance that the children have each remained frozen since death and that the chemistry of their remains has remained stable. Hair analyses revealing COC and BZE show that all three children had ingested coca (Fig. 5 A and B), and the presence of COCE indicates that all three had also ingested alcohol (Fig. 5C). The Maiden had ingested consistently high levels of coca (average baseline values: COC, 6.2 nanograms per milligram hair; BZE, 3.9 nanograms per milligram hair) as long as 1 y before her death. Most significantly, the Maiden markedly increased her consumption of coca at approximately death minus 12 mo (average values following this shift: COC, 17.3 nanograms per milligram hair; BZE, 7.1 nanograms per milligram hair). Peak use at approximately 6 mo, as evidenced by COC and BZE values (COC, 18.6 nanograms per milligram hair; BZE, 8.51 nanograms per milligram hair) was almost three times higher than the earlier values for COC. COCE data from the Maiden suggest that peak alcohol consumption was in her final weeks. Average baseline values (∼0.6 ng COCE per milligram hair) change at approximately death minus 12 mo (1.8 ng COCE per milligram hair), with a small peak at 6 mo (2.6 ng COCE per milligram hair). Peak use in the weeks immediately before death increases rapidly to 8.4 ng COCE per milligram hair. The Llullaillaco Boy and the Lightning Girl had markedly lower values (COCE and COC) than the Maiden (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 1.

Posture of the Maiden shown through scaled excavation photographs and 3D visualizations generated by using the original CT scans (45): (A) in situ photograph of the Maiden’s posture within the shrine [Reprinted with permission from ref. 1. Photography by Johan Reinhard] and (B–D) 3D visualizations of the body: (B) vertical view corresponding to the same position shown in A, (C) corresponding anterior view, and (D) lateral view. The CT data were constrained by the diameters of gantry opening (60 cm) and the field of view (45 cm scanning circle) within the Tomoscan M/EG (Philips), with the upper part of the head, the knees, the lower legs, and the feet consequently missing.

Fig. 2.

Plan view showing the Maiden in situ during excavation. The juxtaposition of the Maiden and her associated artifacts (left to right) suggest careful arrangement, with no displacement of the white feathered headdress (N-26, Table S1) or brown textile (N-34) shrouding her head. The border of the male woolen tunic (N-33) draped across her right shoulder and knee was used to place ceramic plates (N-18), a pedestal pot with lid (N-21), and stirrup pot with vegetal bung (N-22) immediately in front of her, and these remain upright, showing a similar lack of disturbance. Woolen bags containing food (N-10), a cactus thorn comb (N-7), and three female anthropomorphic statues (N-23, N-24, and N-25) were all located immediately around her. Other artifacts have already been recovered. [Reprinted with permission from ref. 1. Photography by Johan Reinhard.]

Fig. 3.

The Maiden’s gastrointestinal tract: (A) 3D visualization of the body with the trace of the three axial views on the right (labeled 1–3) and (B) 3D visualization of the gastrointestinal tract and fecal matter [1, axial view at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra; 2, axial view between the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae; 3, axial view between fourth and fifth sacral vertebrae]. E, esophagus; F, residual food (axial view 1)/feces (axial views 2 and 3); PM, psoas muscles; R, rectum; S, stomach; SI, small intestine.

Fig. 4.

The Maiden’s coca quid shown (A) within the cheek in an anterior photograph of the Maiden’s face [Reprinted with permission from ref. 1. Photography by Johan Reinhard.]. (B) Axial radiograph of the interior of the mouth shows the coca quid (green) held between the teeth. (C and D) Three-dimensional visualizations of the cranium (yellow), teeth (orange), tongue (red), and coca quid (green).

Fig. 5.

LC-MS/MS hair analyses for all three children using 15-mm segments (each approximately 0.2 mg) along the length of the hair from proximal end (21-cm hair shaft length for the Maiden) indicate that all three children had ingested coca, as evidenced by levels of (A) BZE and (B) COC. Concurrent coca and alcohol use, particularly evident in the Maiden’s hair closest to death, is confirmed by (C) the presence of COCE and (D) based on CCOCE/CCOC (data are reproduced in Table S3).

Discussion

Against the background of a longer Andean tradition of sacrifice and ritual killing (notably in the foundations of new buildings) (8), the scale and elaboration of the rites, and the focus on children, coincide with the unprecedented and rapid military–political expansion centered on Cuzco that lasted little more than a century before the Spanish conquest (9). The fact that the empire was based on a high level of social stratification, and powered by corvée labor and the extraction of tribute, both of material and human resources, has long been recognized (10), making it unarguable that behind religiously justified and event-specific explanations lay a sophisticated program aimed at creating stable foundations integrating a massive region. The topographic placement of capacocha victims on highly visible peaks must have been connected to the extension of social control over newly acquired territories. Although the carefully choreographed sacrifice of “donated” children brought direct socioeconomic benefits to tributary groups who supplied them, the ritual would unavoidably—whatever its internal ideological and religious rationale, and however complicit the parents or the wider group—have created a climate of fear. This is implicit in comments made by the Spanish Jesuit missionary and writer Bernabé Cobo (1653) in relation to parents compelled to give up their children, namely that “it was a major offense to show any sadness,” and that “they were obliged to do it with gestures of happiness and satisfaction, as if they were taking their children to bestow upon them a very important reward” (11). Emotional inurement—whether explicitly contrived or only implicitly apprehended by those in control—could create needs that could be converted into allegiance to the imperial system (11–13).

Our diachronic data on the use of coca build on our previous isotope data (4), offering information on status change and habituated coca use. The coca data are consistent with previously published bulk values for these children (4), but notably higher than previously published values for coastal pre-Columbian individuals (14, 15). The Maiden’s hair provides clear evidence that she had increased coca consumption, and the chronology correlates with changes in dietary isotopes at approximately death minus 12 mo. The speed and magnitude of these changes is best explained by the selection of the Maiden as a sacrificial victim and her consequent status change. Given that the bagged hair found with the Maiden was cut at death minus 6 mo, and that we know from later accounts, such as that of the Quechua nobleman Guamán Poma (circa 1615) (16), that the Inca maintained a complex ceremonial calendar of annual events, it may be that some of the changes that we can resolve diachronically were embedded within an intentional and precise schedule of events. Nevertheless, unscheduled events, such as the death of the emperor, droughts, and natural disasters, were also a context for rites in which children were killed. In particular (and even though some doubt may attach to absolute numbers), the early Spanish writer Juan de Betanzos (1557), writing on the testimony of his wife (previously married to the Inca Emperor Atahualpa), makes the claim that 1,000 boys and girls between 5 and 6 y of age, some the children of caciques or local leaders, were gathered in pairs and dressed up to be carried in litters indicative of high rank, and brought to Cuzco as part of the funeral rites of Inca rulers. Betanzos says that there they were killed to serve the Inca and “buried all over the land where the Inca had established residence” (17). Collectively, this information suggests that the staging of events in Cuzco was one part of a rite that also involved considerable distance movement. We can also infer from the account of the Jesuit priest and missionary Hernández Principe (1622) (18) that children could sometimes bypass Cuzco on the journey from their home village to the destination shrine.

Native coca (Erythroxylum spp.) has widespread importance to different cultural groups known to Andean archaeology, as evidenced by its inclusion as funerary goods, through its depiction in religious iconography, and in its frequent mention by the Spanish chroniclers, highlighting its use as a high-status lowland tribute crop (19). Although coca is often reified as a timeless cultural “given,” much is still unknown of changes in the distribution through time of the four cultivar taxa (Table S2). It is understood, however, that, at the height of the Inca Empire, coca was a valued and increasingly controlled resource, so important that at least one ethnic population is known to have been resettled to provide labor for its harvest (20). Inferred imperial monopoly control (21) was broken by the Spanish conquest, with key players such as Hernando Pizarro moving in to supply urban markets in Cuzco and Charcas, and bring it to mining centers such as Potosi (22); the expansion of business may imply that controlled, elite-level ritual use was replaced by a deritualized and more broadly based commercial market.

The sizeable coca quid clenched between the Maiden’s teeth, as evidenced by the CT data, and remnants of chewed leaves around her mouth, show that she was ingesting coca in her final moments. With traditional use of unprocessed coca in modern times, approximately 8 to 10 g of coca leaves are chewed along with illipta (Quechua), a compressed plant ash. This ash is alkaline and helps the extraction of the main active compound in coca leaves, COC, absorbed through the mucous membranes of the mouth (23). The quid, which is kept in the cheek, is sucked, and the juices swallowed. These juices produce tangible levels of COC in blood, plasma, and excretory products (including sweat, saliva, urine, and hair) (24–26). The same metabolites, such as BZE and ecgonine methyl ester, are produced, yet the effects vary widely. Habitual chewers who swallow coca residues when chewing can produce levels of COC in their blood in a similar range to those experienced by users of processed COC: use of 60 g of good leaves per day produces absorption of 100 to 200 mg of COC in the body (23). Significantly, this is not accompanied by the negative signs of addiction that accompany chronic use of processed COC. The differences can be explained by pharmacokinetics: in coca chewers, plasma COC levels peak after approximately 60 min and gradually decrease over a period of several hours (27). This does not produce the drastic changes in brain chemistry that are considered to be the principal reason for COC addiction (28).

The medicinal properties of coca as a stimulant improving oxygen absorption are demonstrated in the treatment of metabolic and physiological conditions, including exhaustion, hunger, and travel and altitude sickness (29). According to our understanding of coca consumption in modern population groups, the following variables can significantly affect the metabolism of coca/COC, and these factors must also be considered in relation to the actual quantity of ingested coca and the cumulative effect of sustained habituated use: First, body mass, which, when comparing the relative ages and sizes of the three children, cannot be ignored; and second, physiology, again an important consideration when examining individuals who are adapted to strenuous activity under conditions of low oxygen/high altitudes—perhaps most notable today among modern Andean miners (24) (Fig. S1).

Andean cultures also value the fermented alcoholic drink chicha. This beverage is usually brewed from maize (Zea mays), although other plants such as algarrobo (Prosopis spp.) have also been used (23, 30). Chicha was an important element of social and ceremonial gatherings, where ritual drunkenness was often obligatory (31); the Inca believed intoxication opened channels to the spiritual realm (32). The detection of COCE in hair is indicative of concurrent COC and alcohol ingestion (33). It is therefore difficult to ascertain drinking behavior from COCE alone. The ratio of COCE to COC (CCOCE/CCOC) in hair should approximate the mean ratio of both compounds in blood during consumption, affording a better assessment of the drinking behavior of the individual (34). High ratios (>20%) probably reflect regular COC use in combination with high alcohol intake. CCOCE/CCOC in the lower range (∼0.0–10%) should show that alcohol was present only occasionally, or in low concentrations during COC use. The CCOCE/CCOC ratios for the Llullaillaco Maiden indicate that coca and alcohol were used together in low to moderate amounts: alcohol intake reaches a peak approximately 6 mo before death (CCOCE/CCOC = 13.7%), decreases slightly, then increases drastically in the last 1.5 mo before death (CCOCE/CCOC = 52.8%), suggesting high alcohol intake coupled with frequent use of coca. The ratios for the Llullaillaco Boy suggest an alcohol intake that was relatively high, with little variation over the length of the hair (range, 39.7–46.4%), but ratios for the younger girl show more variation.

Acllas, or chosen women (the group to which the Maiden must have belonged), received training in weaving and in chicha production (35, 36). We also find reference to the fact that, at approximately the age of puberty, these individuals might be confirmed as priestesses, given to local nobles as wives, or be killed as part of state-sanctioned capacocha rites as described by the Jesuit missionary and humanist José de Acosta (1590) (37). The enrichment of the Maiden’s carbon isotope data in her final months (4), suggestive of increased consumption of C4 plants, may be explained as a combination of the shift to maize as a foodstuff, but also by an increased and thereafter sustained use of chicha-maize and chicha being associated with elite lifeways (31). It is reasonable to assume that chicha was the primary source of alcohol in the Maiden’s system as determined from her hair. At this altitude, being sealed within a ritual structure, meant that death from exposure would have been inevitable in the absence of other proximate causes, but the physiological and psychological effects of coca and chicha must have played a role in this extreme environmental context. Alcohol acts as a sedative (38), and greatly diminishes whole-body sensations of cold discomfort (39), yet its ingestion exacerbates the decrease in core body temperature during cold exposure by impairing the shivering reflex, thus hastening death (40). COC, by contrast, may have potentially beneficial effects on survival in extreme cold conditions, as it induces mild vasoconstriction, improving heat conservation (41). The balance of effects, and which were intended and which mere byproduct, is unclear. It is not possible to argue that the Maiden was rendered senseless only immediately before her death, as the record from her hair shows an extensive period of substantial alcohol and COC absorption after the point at which dietary change indicates elevated status.

The lack of displacement of the Maiden’s clothing and artifacts (her shrouded head, the undisturbed headdress, and artifacts placed on a textile in front of her that is also draped over her knee) suggests that she was heavily sedated, or indeed recently dead, by the time she was entombed. An estimation of the time of death is possible based on gastric contents. Timescales for gastric emptying typically vary from 1 to 3 h for a small-volume meal to 5 to 8 h for a large volume (42). Only limited food remains are visible in the Maiden’s stomach (volume of approximately 7.5 cm3), so it is possible to suggest that she ate her last meal between 2 and 7 h before death. Food and fecal matter can also be seen in the small intestine and large intestine (volume, 262.7 cm3, excluding rectum), and in the rectum, which is filled with fecal matter (volume, 65.5 cm3). This evidence clearly indicates that the Maiden had not recently defecated, and it is possible that high altitude and constant use of coca had contributed a degree of constipation, in view of their weakly sympathomimetic effects, which reduce blood flow and decrease peristalsis (43).

It is likely that coca and alcohol played a dual role at the end of these sacrificial victims’ lives. Understood within the cultural frameworks of Inca religious ideology, both were associated with elite ritual practice. Coca and alcohol were substances that induced altered states interpreted as sacred, and which could suggest to victims and those associated with them the proximity of the divine beings whose continued benevolence was underwritten by these rites (44). From a cross-cultural perspective, the psychologically deadening, disorienting, and mood-modifying effects of these psychoactive compounds on young victims, for whom any kind of informed consent to their own deaths cannot be unproblematically presumed, should not be downplayed (13).

Our results here amplify our previous findings (4) concerning status change, and add to our understanding of the culminating steps of the capacocha rite. There is clear evidence for structured behavior that saw the children being treated differentially from one another. This is manifest in terms of their physical appearance—the elaborate braiding of the Maiden’s hair and headdress for example, vs. the nit-infested hair of the Llullaillaco Boy and less well kept hair from the Lightning Girl—as well as the clothing and artifacts that accompanied them. It is also represented by the significantly higher values for coca and alcohol in the Maiden’s hair. Nevertheless, the BZE values for the two younger children suggest that there is some concordance with the ritual timeline that we have now established for the Maiden—most significantly with the Lightning Girl’s hair at death minus 6 mo. This does not in itself mean that all three were part of the same ceremony (with the young boy and girl as “attendants,” for instance)—although that remains plausible—rather, that the effects of coca and alcohol were closely integrated into the imperial mode of Inca child sacrifice.

Materials and Methods

CT scan data collected by Previgliano et al. (45) were further analyzed (including a revised age assessment) by using data segmentation methods described by Lynnerup and Villa (46, 47). Cut scalp hair samples (collected by A.S.W. in 2003) were defrosted and prepared for LC-MS/MS as follows. Oriented 15-mm fiber segments of approximately 0.2 mg (approximately three fibers) were weighed into Pyrex boiling tubes, 300 μL 0.1 M hydrochloric acid was added, and they were then incubated at 45 °C for 20 h with internal standards BZE-D3, COC-D3 and COCE -D3 (LGC Promochem). Sample extracts were filtered through a 3-mL Luer-Lok syringe (13-mm diameter) with attached Minispike Acrodisc GHP membrane syringe filters with a pore size of 0.2 μm (VWR International), which had been previously conditioned with HPLC-grade methanol. Samples were blown down under nitrogen at 45 °C and reconstituted with 200 μL HPLC-grade methanol. Self-reporting COC users undergoing rehabilitation treatment were analyzed as positive controls with informed consent; reviewed by the Biological, Natural, and Physical Sciences ethics panel (Bradford). A negative control sample was provided by E.L.B. Hair certified reference materials were analyzed for quality assurance purposes [40702 Medidrug DHF 3/01-A H-Plus lot 10103 (BZE, 0.79 ng/mg; COC, 1.48 ng/mg); 40711 Medidrug DHF 3/06-A H-Plus lot 10603 (BZE, 3.18 ng/mg; COC, 2.68 ng/mg); Medichem]. A 5-μL sample extract was injected onto a Synergi Fusion RP Column (150 × 2 mm internal diameter, 4-μm particle size; Phenomenex). Separation used a model 2695 separations module (Waters) interfaced with a Micromass Quattro Ultima triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters), with MassLynx 4.0 software, using electrospray ionization in positive ion mode (ES+). Gradient elution was performed over a period of 30 min with mobile phase A [5% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, 95% water with 0.05% formic acid] and mobile phase B (100% acetonitrile with 0.05% formic acid). All standards (COC hydrochloride, BZE and COCE; LGC Promochem) were linear over the calibration range (1–500 pg/5 μL; r2 = 0.99) using Masslynx 4.0 software. Chromatography data were reproducible at 2-mg and 0.2-mg sample sizes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Larry Cartmell (Oklahoma Pathology Associates), Rob Janaway, Dr. Ben Stern, Dr. Richard Telford, and Prof. Anna Nicolaou (University of Bradford) for contributions to the study; and Sarah Wright for proofreading and editorial support. This study was supported by the National Geographic Society, which supported the research excavations at Llullaillaco; the National Council for Scientific Research (CONICET) in Argentina (C.C.); the Wellcome Trust (A.S.W.); and Dr. Randy Donahue (University of Bradford Palaeopharmacology Initiative).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1305117110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Reinhard J, Ceruti MC. Inca Rituals and Sacred Mountains: A Study of the World’s Highest Archaeological Sites. Los Angeles: UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verano JW. Trophy head-taking and human sacrifice in Andean South America. In: Silverman H, Isbell WH, editors. The Handbook of South American Archaeology. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 1047–1060. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corthals A, et al. Detecting the immune system response of a 500 year-old Inca mummy. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e41244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson AS, et al. Stable isotope and DNA evidence for ritual sequences in Inca child sacrifice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(42):16456–16461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704276104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson AS, Gilbert MTP. Hair and nail. In: Thompson T, Black S, editors. Forensic Human Identification: An Introduction. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 147–174. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ceruti C. Human bodies as objects of dedication at Inca mountain shrines (northwest Argentina) World Archaeol. 2004;36(1):103–122. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aufderheide AC. The Scientific Study of Mummies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyerdahl T, Sandweiss DH, Narváev A. Pyramids of Túcume. New York: Thames and Hudson; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Altroy TN. The Incas. Oxford: Blackwell; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murra J (1975) [Formaciones Económicas y Políticas del Mundo Andino] (Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Lima). Spanish.

- 11.Benson EP, Cook AG. Ritual Sacrifice in Ancient Peru. Austin: Univ Texas Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duviols P. La Capacocha. Allpanchis. 1976;9:11–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nell V. Cruelty’s rewards: The gratifications of perpetrators and spectators. Behav Brain Sci. 2006;29(3):211–224. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x06009058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cartmell LW, Aufderheide AC, Springfield A, Weems C, Arriaza B. The frequency and antiquity of prehistoric coca-leaf-chewing practices in Northern Chile: Radioimmunoassay of a cocaine metabolite in human-mummy hair. Latin Am Antiquity. 1991;2(3):260–268. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bray W, Dollery C. Coca chewing and high altitude stress: A spurious correlation. Curr Anthropol. 1983;24(3):269–282. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Besom T. Of Summits and Sacrifice: An Ethnohistoric Study of Inka Religious Practices. Austin: Univ Texas Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Betanzos J. Narratives of the Incas. Austin: Univ Texas Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández Principe R. Mitología Andina [1622] Inca. 1923;1:25–78. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Plowman T (1984) The origin, evolution and diffusion of coca Erythroxylum spp. Pre-Columbian Plant Migration. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, ed Stone D (Harvard Univ Press, Cambridge, MA), Vol 76, pp 146–156.

- 20.Schramm R. Visita of the Churumatas. In: Pillsbury J, editor. Documentary Sources for Andean Studies. Vol 3. Norman: Univ Oklahoma Press; 2008. pp. 721–722. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parkerson PT. The Inca coca monopoly: Fact or legal fiction? Proc Am Philos Soc. 1983;127(2):107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabai RV. Pizarro, Hernando. In: Pillsbury J, editor. Documentary Sources for Andean Studies. Norman: Univ Oklahoma Press; 2008. pp. 520–524. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rätsch C. The Encyclopaedia of Psychoactive Plants. Rochester: Park Street Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henderson GL, Harkey MR, Zhou C, Jones RT. Cocaine and metabolite concentrations in the hair of South American coca chewers. J Anal Toxicol. 1992;16(3):199–201. doi: 10.1093/jat/16.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homstedt B, Lindgren JE, Rivier L, Plowman T. Cocaine in blood of coca chewers. J Ethnopharmacol. 1979;1(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(79)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.elSohly MA, Stanford DF, elSohly HN. Coca tea and urinalysis for cocaine metabolites. J Anal Toxicol. 1986;10(6):256. doi: 10.1093/jat/10.6.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashley C, Hitzemann RC. Pharmacology of cocaine. In: Swann A, Volkow ND, editors. Cocaine in the Brain. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Isenschmid DS. Cocaine. In: Levine B, editor. Principles of Forensic Toxicology. Washington, DC: AACC Press; 2006. pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna JM. Coca leaf use in southern Peru: Some biosocial aspects. Am Anthropol. 1974;76(2):281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashida F. Ancient beer and modern brewers: Ethnoarchaeological observations of chicha production in two regions of the north coast of Peru. J Anthropol Archaeol. 2008;27:161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bray TL. Inka pottery as culinary equipment: Food, fasting, and gender in imperial state design. Latin Am Antiquity. 2003;14(1):3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hastorff CA, Johannessen S. Pre-Hispanic political change and the role of maize in the Central Andes of Peru. Am Anthropol. 1993;95:115–138. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landry MJ. An overview of cocaethylene, an alcohol-derived, psychoactive, cocaine metabolite. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24(3):273–276. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pragst F, Yegles M. Alcohol markers in hair. In: Kintz P, editor. Analytical and Practical Aspects of Drug Testing in Hair. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 288–317. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cieza de León P. In: The Incas of Pedro Cieza de León. Von Hagen VW, editor. Norman, OK: Univ Oklahoma Press; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cobo B. History of the Inca Empire. Austin: Univ Texas Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Acosta J (1590) Historia Natural y Moral de las Indias; trans López-Morillas F (2002) [Natural and Moral History of the Indians] (Duke University Press, Durham), Spanish.

- 38.Paton A. Alcohol in the body. BMJ. 2005;330(7482):85–87. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7482.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoda T, et al. Effects of alcohol on autonomic responses and thermal sensation during cold exposure in humans. Alcohol. 2008;42(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freund BJ, O’Brien C, Young AJ. Alcohol ingestion and temperature regulation during cold exposure. J Wilderness Med. 1994;5(1):88–98. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanna JM. Responses of Quechua Indians to coca ingestion during cold exposure. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1971;34(2):273–277. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330340210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madea B, Hanssge C. Timing of death. In: Payne-James J, Busuttil A, Smock W, editors. Forensic Medicine: Clinical and Pathological Aspects. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zubrycki EM, Giordano M, Sanberg PR. The effects of cocaine on multivariate locomotor behavior and defecation. Behav Brain Res. 1990;36(1-2):155–159. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(90)90169-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen C. Body and soul in Quechua thought. J Latin Am Lore. 1982;8:179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Previgliano CH, Ceruti C, Reinhard J, Araoz FA, Diez JG. Radiologic evaluation of the Llullaillaco mummies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(6):1473–1479. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.6.1811473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lynnerup N. Computed Tomography Scanning and Three-Dimensional Visualization of Mummies and Bog Bodies. In: Pinhasi R, Mays S, editors. Advances in Human Palaeopathology. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villa C, Lynnerup N. Hounsfield Units ranges in CT-scans of bog bodies and mummies. Anthropol Anz. 2012;69(2):127–145. doi: 10.1127/0003-5548/2012/0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.