Abstract

Community organizing is a successful method to leverage resources and build community capacity to identify and intervene upon health issues. However, published accounts documenting the systematic facilitation of the process are limited. This qualitative analysis explored community organizing using data collected as part of the Study to Prevent Alcohol Related Consequences (SPARC), a randomized community trial of 10 North Carolina colleges focused on reducing consequences of high-risk drinking among college students. We sought to develop and confirm use of a community-organizing model, based in practice, illustrating an authentic process of organizing campus and community stakeholders for public health change. Using the grounded theory approach, we analyzed and interpreted data from three waves of individual interviews with full-time community organizers on five SPARC intervention campuses. A five-phase community-organizing model was developed and its use was confirmed. This model may serve as a practical guide for public health interventions utilizing community-organizing approaches.

Over the last several decades, the field of health education and health promotion has extended its focus on individually-based interventions to include social and environmental factors that affect health behavior. This ecological approach has broadened awareness of the influences on health and emphasized the importance of community-based approaches that utilize interventions targeted at various levels of the social environment to affect individual behavior and population-level changes (McLeroy et al, 1988).

One such strategy that has been used to promote such large-scale, enduring changes among individuals and within the community is community organizing (Minkler, 2005). Simply defined, community organizing is a process by which diverse community groups determine issues to be addressed and identify strategies to effect positive change to achieve one common goal. Community organizing starts “where the people are,” emphasizes participation by community members, and throughout the process, promotes individual and community capacity as people gain skills to assess needs, plan strategically, and implement action steps (Nyswander, 1956; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2005). A “driving force” of a community leader or community organizer (CO) is sometimes needed to spur action and guide the effort (Littleton et al., 2002).

Although community organizing often occurs when lay community members are dissatisfied with current conditions, and thus organize for change, the approach has increased in prominence as a planned intervention method for community members to mobilize, leverage existing resources, and build local capacity to tackle key public health issues. For example, numerous public health initiatives, including a number of community trials, have used community organizing to restrict youth access to alcohol and tobacco (Blaine et al., 1997; Wagenaar et al., 2000; Toomey & Fabian, 2006), promote positive youth development (Cheadle et al., 2001; Kegler & Wyatt, 2003), reduce cardiovascular disease risk (Cornell et al., 2008), and change sex and drug behaviors to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS (Rietmeijer et al., 1996; Silvestre et al., 2006).

The results of studies using community organizing are mixed, with some studies showing null to modest effects (Cheadle et al., 2001; Toomey & Fabian, 2006) while others, including HIV prevention programs (Rietmeijer et al., 1996; Higgins et al., 1996; Downing et al., 2005), the Tobacco Policy Options for Prevention (TPOP) study (Blaine et al., 1997), and the Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol (CMCA) study (Wagenaar et al., 2000), suggest more promising results. These trials used formative research to tailor programs for high-risk subsets of the communities. Those with more modest or mediocre effects revealed methodological and study design flaws, limitations of the intervention, as well as small effect sizes (Merzel & D’Afflitti, 2003).

Community organizing occurs within the dynamics of a community and therefore, a community leader or community organizer (CO) is often needed to organize and spur action. It is important for the organizer to possess a broad range of competencies to facilitate the co-learning and action-oriented processes that are inherent to community organizing. The organizer serves in many roles, such as planner, administrator, agitator, decision-maker, facilitator of indigenous and organizational leadership development, interventionist, public relations expert, and service provider. Additionally, the organizer must thoroughly understand community characteristics and power dynamics and be able to spark positive action to improve conditions (Alinsky 1967; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2005).

Community organizing on college campuses may present unique challenges because of their complex organizational, social, and cultural structures, and the existing relationship with the surrounding community. Oftentimes, colleges and communities do not work together on issues, as Wechsler and colleagues (2000) found when they surveyed 734 college administrators regarding prevention efforts to reduce binge drinking. While most colleges reported having a campus alcohol specialist or task force, far fewer reported working with the larger community through organized efforts such as community agreements or neighborhood exchanges to address problems.

However, this is not to say that campus-community collaborations cannot succeed. Gebhardt, Kaphingst, and DeJong (2000) explained how a campus-community coalition in New York was able to decrease reports of consequences of off-campus student drinking by increasing enforcement in targeted neighborhoods and maintaining a hotline to report student drinking and other off-campus problems. Additionally, Nelson, Weitzman, and Wechsler (2005) reported significant reductions in drinking and driving among colleges participating in the A Matter of Degree (AMOD) program, a campus-community initiative to reduce college binge drinking.

Given this context and the complexities of organizing a campus-community effort, we sought to explore and characterize the authentic process of community organizing used by university-based COs through three annual waves of qualitative, in-depth interviews with eight full-time COs. Using the grounded theory approach, the goals were to develop and confirm the use of a community organizing model, depicting the authentic process used to create broad-based coalitions and implement environmental change on college campuses and in surrounding communities.

Design of the Parent Study

Data for this study were collected as part of the process evaluation of the Study to Prevent Alcohol-Related Consequences (SPARC), an ongoing NIAAA-funded, 10-campus, randomized community trial in North Carolina. Five universities serve as intervention schools and five serve as comparison schools. The goal of the parent study is to test whether a community-organizing intervention, promoting the implementation of environmental strategies, reduces high-risk alcohol drinking and associated consequences among college students.

Intervention and comparison schools, matched on undergraduate enrollment and funding source (public vs. private), were randomly assigned to the intervention or comparison condition. Undergraduate fulltime enrollment of the ten schools ranged from 2,684 to 16,144. The intervention and comparison conditions each included one private and four public universities.

The SPARC Community-Organizing Intervention

The SPARC intervention used community organizing to implement environmental strategies targeted at high-risk alcohol reduction. A full-time CO was hired at all five intervention schools, with special emphasis placed on hiring an individual who was familiar with the university, but who also had experience in community organizing, substance use prevention and/or treatment, and knowledge of environmental approaches to health behavior change. COs were charged with establishing campus-community coalitions, which in turn, developed strategic plans targeting campus environmental factors. Plans included strategies that were either effective in reducing high-risk drinking and its consequences or were identified as promising by experts in the field (National Institutes of Health, 2002).

Specific strategies were not prescribed for each coalition’s implementation. Instead, coalitions were allowed to choose from a matrix of “best and most promising” (BMP) strategies based on several published sources (DeJong & Langford, 2002; National Institutes of Health, 2002; Toomey & Wagenaar, 2002). This latitude was important to the intervention in order to give the campus-community partnerships the ability to choose the types of strategies that would work best in their individual community. Table 1 provides a list of the BMP strategies from which coalitions chose. The SPARC study team at Wake Forest University School of Medicine (WFUSM) provided technical assistance and training on community organizing and environmental strategy implementation during the intervention.

Table 1.

Best and Most Promising Strategies to Reduce High-Risk Alcohol Use

| SPARC Measure Strategy | Number of Schools Using Strategy (n=5) |

|---|---|

| Availability | |

| Restrict provision of alcohol to underage or intoxicated students | 5 |

| Increase/improve coordination between campus & community police | 5 |

| Restrict alcohol purchases, possession | 4 |

| Restrict alcohol use at campus events | 3 |

| Increase responsible beverage service policies & practices | 2 |

| Conduct compliance checks | 2 |

| Educate landlords about their responsibilities and liabilities | 2 |

| Price/Marketing | |

| Limit amount, type & placement of pro-drinking messages seen on campus | 2 |

| Social Norms | |

| Establish consistent disciplinary actions associated with policy violations | 5 |

| Create campaign to correct misperceptions about alcohol use | 4 |

| Enhance awareness of personal liability | 4 |

| Provide notifications to new students, parents of alcohol policies, penalties | 4 |

| Provide alternative late night programs | 2 |

| Provide alcohol-free activities | 2 |

| Provide parental notification of student alcohol violations | 1 |

| Create policy to provide brief motivational module for all freshmen | 1 |

| Harm Minimization | |

| Enact party monitoring program | 3 |

| Create and utilize safe ride program | 2 |

| Increase harm reduction presence at large-scale campus events | 1 |

METHODS

The analysis explored the community organizing process among intervention schools, as it was occurring, using COs as key informants. A theoretical model describing community organizing in the context of the university culture was developed based on CO interviews from Year 1. Analysis of Year 1 data lead to the inclusion of additional interview questions in Years 2 and 3 to more fully understand the use of the model. Analysis of Year 2 and 3 interviews confirmed the use of the model in practice and identified key challenges to its implementation.

The WFUSM Institutional Review Board (IRB) provided human participant review and study oversight. IRBs from the study universities either reviewed and approved the study or established oversight agreements with the WFUSM IRB.

Interview Methods

The study used in-depth interviews with the COs because the methodology provides an opportunity to investigate participant responses and reactions to issues related to their community-organizing experiences more fully. Importantly, it also allows new areas of inquiry to emerge. This inductive approach can reveal key perspectives and nuances that researchers may not foresee (Patton, 1990; Atkinson, 1998; Eng et al., 2005; Rhodes & Benfield, 2006).

Study team members experienced in community organizing conducted five individual in-depth interviews with the COs in the Fall/Winter of 2004, 2005, and 2006. Interviewers used a semi-structured interviewer’s guide, which covered the interviews’ sequence and content (Patton, 1990; Seidman, 1998). The development of the guide included an iterative process that involved brainstorming potential domains and constructs pertinent to the study, review of the literature (Eng et al., 2005), and development, review, and revisions of potential questions.

Two to three study team members were present during each interview; one served as the primary interviewer, and the others took notes. The note taker also recorded data regarding the COs’ nonverbal reactions. All interviews were audio-recorded, and averaged 60 minutes in length. After each interview, the interviewers debriefed and documented initial general impressions about the process and content of the interview. All 15 audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were verified by reviewing each of them while listening to the audio-recorded interview. Personal identifiers were removed from transcripts.

Analysis

Grounded theory, which relies on an inductive approach to data analysis, was used to analyze the transcripts. Rather than beginning with a preconceived notion of what could be occurring, this approach focuses on understanding a wide array of experiences and building understanding grounded in real-world patterns as they occur (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Transcripts were analyzed using a multiple-stage interpretive thematic analysis. First, five members of the research team read the same Year 1 transcript twice and developed preliminary codes separately. Using an inductive method (Adelman, 1981; Patton, 1990; Ramirez-Valles, 1999; Silverman, 2001), the analysis focused first on the organization of transcript data into broad conceptual categories, and then on more refined coding. The researchers met to compare and contrast conceptual categories. Comparison-based memos were used to develop codes and a data dictionary. Subsequently, the remaining four transcripts from Year 1 were distributed to each researcher so that each transcript was read, reread, and coded separately by at least two researchers. New codes were added as needed.

After coding the assigned transcripts, the study team members met to compare codes and began the process of theme development. Similarities and differences across interviews were examined and themes developed and revised accordingly. The data generated were combined with the researchers’ knowledge of the community organizing process and with previous research to interpret the data. New questions were added to the interview protocols for Years 2 and 3 to more fully assess model use. Data from Year 1 informed the development of the model, while data from Years 2 and 3 contributed to the confirmation of model use in practice.

RESULTS

As described before, each intervention school hired a CO. The CO was interviewed during annual site visits by the SPARC study team. Over the course of the three-year intervention, a total of eight different COs were interviewed, due to turnover. All but one of the eight COs was female; ages ranged from 25 to 51. Seven COs had Master’s degrees in social work, counseling, or a related field, and the eighth had a Bachelor’s degree in secondary education. Previously, five worked as counselors in substance abuse, while six had previous experience working in a university system. COs were located on campus and housed in three types of departments: Student Affairs, University Counseling, and Student Health Services.

Development of a Community Organizing Model: Inputs, Process, and Outcomes

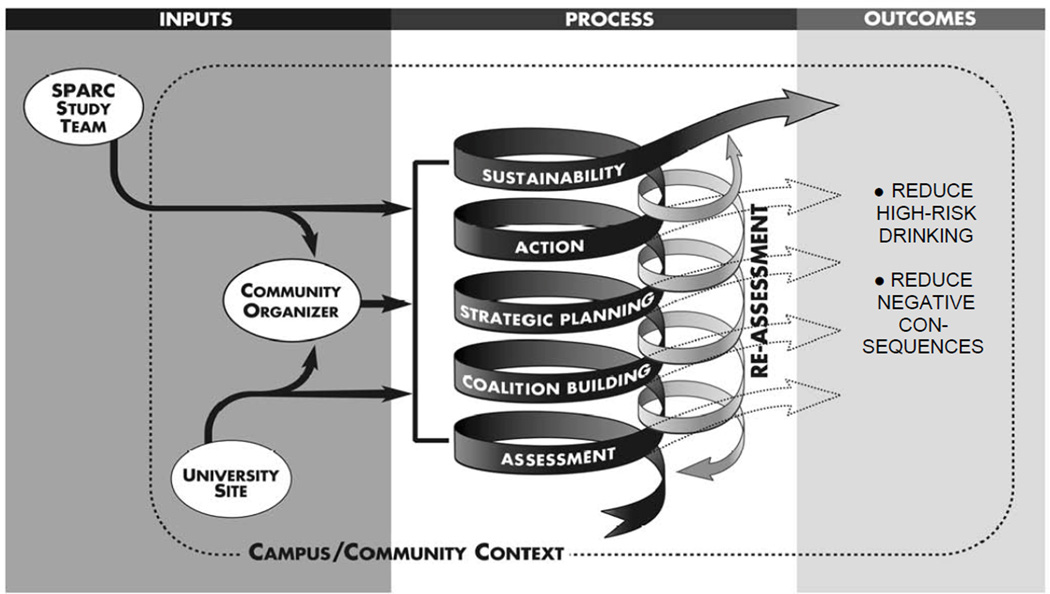

The community organizing conceptual model (Figure 1) was developed using an iterative process based on Year 1 CO interviews, literature review, and input from the multidisciplinary SPARC study team, including public health practitioners, developmental psychologists, sociologists, an emergency medicine physician, a pediatric researcher, a communication scientist, and several biostatisticians. Feedback was solicited from COs for final revisions. Multiple models were consulted, but none captured the community organizing and coalition building experience as described by the community organizers in this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the community organizing process

The model borrows a number of characteristics from other community organizing and coalition models and theories to create one that is distinct for this effort of community organizing on college campuses to implement environmental changes. COs in this project were similar to those depicted in the Community Organization and Development model (Braithwaite et al., 1994) in that several were from outside the institution and had to engage in initial steps of getting to know the community and culture, as well as gain authority and credibility to establish a coalition. COs received training and technical assistance from the SPARC study team on community organizing and environmental approaches.

Additionally, the model has similar structural dimensions as the Community Coalition Action Theory (Butterfoss & Kegler, 2002) because our goal was to show phases that the community organizers and coalitions progressed through to achieve study outcomes. However, because the parent study was focused on reducing high-risk drinking behaviors of college students through environmental changes, our implementation model is less focused on the coalition building and organizational structures and more focused on the steps that the COs and coalitions took to achieve the study’s primary outcomes.

Finally, because SPARC is based on a social action model of community organizing, primarily concerned with increasing the community’s problem-solving ability and achieving concrete changes, while shifting the imbalances of power between the community and the university when warranted, other models were consulted including Alinsky’s Social Action Model (1967) and Rothman’s Community Organization Model (Rothman & Tropman, 1987).

The SPARC model, as depicted in Figure 1, is comprised of three key elements (inputs, process, and outcomes). Community organizing is identified as a bidirectional process, which is flexible and iterative, rather than fixed and linear. Outcomes may occur after any of the phases.

Inputs

Inputs (e.g., resources and technical assistance) were identified as the key contributions to the process of community organizing. These included the university campus and the larger community in which it is situated, the SPARC study team, and the CO. Campus inputs included university administrators and other personnel, such as staff from student health services. Examples of community inputs include partnerships with law enforcement and landlords.

Process Phases

The community organizing process consisted of five phases: community assessment, coalition building, strategic planning, action, and sustainability.

Assessment

CO’s carried out this first phase of the model using the College Alcohol Risk Assessment Guide developed by the Higher Education Center (Ryan, Colthurst, & Segars, 2008) to identify and rate the relative importance of factors that contributed to alcohol use and associated consequences on their individual campuses. They assessed both the problem of alcohol use and the power dynamics of their campus.

Extant data from multiple sources including student health, police and community records, and existing campus data sources (e.g., the CORE Institute of Alcohol and Drug Survey, [Presley, Meilman, & Lyerla, 1994]), enabled COs to develop a comprehensive picture of the issue, past approaches, and the general sentiments of potential key stakeholders at the university and within the community. This phase laid the foundation on which COs identified key stakeholders for recruitment to the campus-community coalition, while simultaneously providing important data for use during the subsequent phases.

Coalition Building

The second phase of the community organizing model focused on building the university-community coalition. COs identified the interests of key stakeholders, making the issue of high-risk alcohol use as salient as possible and encouraging coalition involvement. Relational meetings were conducted to recruit key stakeholders such as university representatives from various departments, student groups and community organizations.

Strategic Planning

During this phase, coalitions created comprehensive strategic plans of environmental strategies, including specific actions and efforts to ensure long-term sustainability. Based on the principle that the culture of each campus and community is unique, specific strategies were not prescribed by the SPARC study team for each coalition’s implementation. Instead, the coalition selected tactics from the matrix of “best and most promising” strategies. Each site’s plan had to include strategies from at least three of the four areas in the matrix:

Alcohol Availability, Harm Minimization, Social Norms and Alcohol Price and Marketing.

Action

After the strategic planning process, coalitions began implementation of their selected strategies. During this phase, coalitions used collaboration, communication, and coordination to implement planned activities on campus and in the community.

Sustainability

This phase focused on maintaining the coalition, as well as the implemented strategies. Also of importance was sustaining the process of community organizing to achieve change.

Reassessment Pathway

An important feature of the SPARC community organizing model is the reassessment pathway, which allows shifts to previous phases at any time. The pathway reflects the coalitions’ and COs’ need to re-evaluate current efforts and situations based on new information.

Outcomes

The campus-community organizing process is intended to change the study’s primary outcomes: reducing high-risk drinking and associated consequences among college students through the use of environmental strategies.

Although the creation of the model was based on CO accounts of their actual organizing experience, confirmation of the model was important to establish the completeness of the model and its accuracy in depicting how the process collectively happened on the campuses. Data from Years 2 and 3 were analyzed using the same method as in Year 1. Themes from Years 2 and 3 were compared to Year 1 themes.

Confirmation of Model Use in Practice

Community Assessment

COs reported actively engaging in a systematic process that mirrored the developed community organizing model (Figure 1), beginning with their focus on community assessment and learning about the university culture. Organizers conducted relational meetings with stakeholders, averaging over 100 meetings per site. COs recruited coalition members, not only based on their interest in the issue of high-risk drinking, but also on the resources and skills they could contribute to the coalition. For example, key stakeholders who had positional authority and networking connections with various constituencies on and off campus were intentionally recruited. Also, those who had desirable skills, such as advocacy experience and knowledge of the alcohol issue were invited to participate. In addition, student groups and undergraduate classes were targeted for recruitment to engage students in the process.

Recruiting community members was also important to the COs, but it was not an easy task. A CO described how some community members felt when invited to join the coalition:

They [community members] are not vested in the University. They just felt like “These are not my issues. You need to deal with your own stuff.”

Despite some initial disinterest, COs were able to use their community organizing skills to find others who were interested in the issue:

My approach to gaining community support was to go to neighborhood meetings. Through someone I had a one-on-one meeting with, I went to a neighborhood meeting. I found people who had a passion for the issue and wanted to do something about it.

Coalition Building

As a result of the assessment phase, COs developed broad-based coalitions with representation from the university and community. Table 2 provides a breakdown of coalition membership.

Table 2.

Coalition Size and Composition

| Number of Members |

Campus Administration |

Community Member |

Student | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 12 | 10 (84%) | 1 (8%) | 1 (8%) |

| Site 2 | 21 | 15 (71%) | 2 (10%) | 4 (19%) |

| Site 3 | 29 | 19 (66%) | 5 (17%) | 5 (17%) |

| Site 4 | 11 | 5 (45%) | 5 (45%) | 1 (10%) |

| Site 5 | 33 | 13 (40%) | 15 (45%) | 5 (15%) |

A coalition was formed at each campus, and regularly scheduled meetings began between May and July, 2004 at four of the five intervention schools. A fifth school did not start meeting until October 2004 because of a protracted institutional process of hiring a community organizer. On average, the initial Assessment and Coalition Building stages lasted four to five months from assessment to the first coalition meeting.

Strategic Planning

Coalitions took between five and ten months to develop their strategic plans, which were reviewed and approved by the SPARC study team. COs reported that implementation of their strategic plans happened quickly, once they obtained approval from their institution and the SPARC study team.

Because several COs were new to their university or had not been in their position for an extended period of time, having members experienced with the university culture proved helpful as the strategic plans were developed. As a CO explained,

Having different people who had been here a lot longer than me and [knew] the policies of the campus was helpful. They’d say, “We need to hit it from this angle. We still get what we want, but we use the language that they will accept.”

Action

COs reported implementing a range of activities including social norms marketing campaigns, developing and implementing a Safe Rides program, securing commitment from area landlords to track student alcohol violations in apartment complexes, hosting meetings with area retailers to improve responsible service practices, increasing communication and collaboration between campus and community law enforcement, setting up a "Citizen Scholars program" where privileges (e.g., preferential campus housing and parking spots) were tied to clean alcohol records, and hosting meetings to draft or amend institutional policies regarding alcohol use on campus.

About three-quarters (74%, n=269) of coalition activities focused on raising awareness of high-risk alcohol use; 20% were related to campus policy and 6% to enforcement efforts. During this same period, more than two-thirds (69%) of activities were focused solely on campus-based strategies; 18% on strategies addressing both campus and community issues; and 12% on community-based strategies.

Sustainability

COs described the value that key stakeholders brought to their coalition. Because they purposefully recruited them to help identify key issues and brainstorm potential solutions, the collaborative effort resulted in some of the coalition’s strategies being institutionalized during the strategic planning phase. For example, activities were planned with key stakeholder buy-in, leading to departments or other entities assuming responsibility for the coalition-developed strategy. Additionally, coalitions targeted alcohol use policies to increase the sustainability of their efforts. Across the five intervention schools, one off-campus institutional policy and 11 campus policies were adopted. The campus policies included increased sanctions for student alcohol violations, benefits for students in good standing, new late night programming, ban on alcohol flyers in residence halls, restrictions on alcohol paraphernalia, inter-departmental procedures for better communication and reporting, dual judicial policies to address off-campus behavior, and clarity on student code of conduct.

All COs reported at least one activity sustained by the university, and some reported sustainability of community activities. Sustainability activities included securing commitment by the board of trustees to fully fund a coalition-initiated Safe Rides program; conducting meetings with top and mid-level campus administrators to promote long-term support of several current coalition activities; applying for grant funds to sustain activities; and building relationships with a local non-profit agency to explore the incorporation of coalition strategies into the mission of the agency. Additionally, at one school all local law enforcement agencies in the community agreed to donate 16 hours per month to increase compliance checks and alcohol enforcement during high-risk times. The CO explained,

Our police officers have committed to doing compliance checks after SPARC is gone and have committed funding to do them each year. Before SPARC, 30 to 33 outlets were being checked. Now all of the public establishments are being checked, which is about 170+ outlets.

Reassessment Pathway

COs also described numerous occasions where a previous phase was revisited to evaluate initiatives and plan new ones. COs reported that even after carefully completing an initial assessment, developing a broad-based coalition, and creating a strategic plan, the coalition building and assessment phases needed to be revisited to make mid-course corrections. Examples provided by the COs included: recruiting new members to assist with specific strategy implementation and collecting supplemental data to support a policy. COs described these adjustments as critical to the success of the coalition and the community organizing process.

They also used the reassessment pathway to reposition coalition activities, such as applying for quick-turn-around funding opportunities, explaining that they had to “strike while the iron is hot.” Another CO explained how the coalition revisited their strategic plan because a new issue arose on campus due to the success of the school’s football team:

Tailgating is a real issue now. The reason being that not only have they (the school) increased the tailgating sites, but they have not increased monies to the police officers to increase enforcement. Nor have they created an alcohol policy of the tailgating sites. So, our (coalition) Leadership Team is going to develop a plan for how to do this in a more structured way.

In addition to providing specific examples of sustainability, analysis of the data revealed that what had been sustained at each campus varied. For some universities, sustainability meant sustaining the CO position and increasing the university’s commitment to the community organizing process. More often, however, sustainability was focused on maintaining the action and programs that the community organizing process sparked.

DISCUSSION

The in-depth qualitative data used for this study enabled the creation of the theoretical framework of the community organizing process on college campuses. Model use in practice was subsequently confirmed through additional years of data analysis and interpretation. The main theme emerging from the analysis is that community organizing in a university context creates unique challenges for the COs, requiring them to strategically plan each phase of the organizing process, including both university and community members, while being flexible to deal with new opportunities or issues that arise. Various principles from community organizing and coalition building models were used (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2005; McKnight, 1987; Alinsky, 1967; Bracht & Kingsbury, 1999; Rothman, 2001), resulting in a hybrid process that showed modest challenges in model use, distinct to the university setting.

Unique to this model was the primary input of a community organizer on the college campus. While many of them were not “experts” on their campus, they used critical steps in the community organizing process to determine the extent of alcohol use at their university, become more familiar with the university culture and the community’s perspective on the issue. Additionally, they identified stakeholders for coalition membership who could aid in strategy implementation. The initial assessment also helped them identify gaps, such as weak or non-existent policies concerning on-campus alcohol use, enabling the coalitions to target those gaps with specific strategies during the strategic planning and action phases.

Ideally, the COs would have been an existing employee of the host institution with a background in substance use and community organizing. However, the universities participating in this study did not have this resource and were forced to recruit for the position. Therefore, the COs had little former connection or association with their campus when the project began, although each of them lived in the larger community surrounding the university. Determining which qualities are more important for the CO to have, knowing the campus culture versus experience in community organizing and substance use, are typical barriers that a university may face as they attempt to tackle the underage drinking issue by working through campus-community partnerships. Zakocs and colleagues (2008) reported that assigning a university employee to facilitate a partnership with community organizing skills was one key factor related to higher-developed campus-community partnerships. Other research has shown that connection with the external community is also important. Alexander and colleagues (2006) reported that COs with limited connection to the community they are serving may be less able to recruit coalition members from the community and have less knowledge of existing problems that could affect the coalition.

The universities in this study chose to hire COs who were familiar with the larger community and had previous knowledge of substance use instead of hiring someone from within the university who did not have those skills or the time to devote to the position. The COs overcame the barrier of being new to the university by using basic community organizing principles, such as one-on-one relational meetings, to concurrently build the coalition and learn the campus and community, while also assessing community strengths and needs.

Each of the intervention schools was able to create a broad-based coalition, made up of campus and community representatives. Because the coalitions were lead by COs, who were employees of their host institution, the COs were aware of the possibility of a perception that the university would drive the coalition’s priorities and ultimately had the power. Research has documented that forming a partnership from within the university context can be dominated by universities due to the organizational framework in which it was formed (Cherry & Shefner, 2004). Having a university-community coalition led by a CO representing the university, by reality or perception, can impede the process of creating authentic collaboration and equality among members. Despite the best efforts of the most skilled CO, the perception that the university’s wisdom exceeds the community’s understanding of its needs can lead to the university dominating the problem-solving efforts, and in some cases, prioritizing its needs over the community’s (Freyder & O’Toole, 2000). This perception could foster resentment and mistrust among the coalition’s community representatives. This issue did not emerge for the coalitions in this study, possibly because focused training heightened the COs’ awareness of potential power imbalances, or perhaps because the coalition members worked collectively to identify and address the issues.

Ultimately, COs navigated these challenges by relying on their community organizing training and experiences, learning the university culture and recognizing the strengths and limitations of the coalitions. These challenges, which are inherent to coalitions, did not detrimentally affect the CO’s ability to organize a broad-based coalition, the coalition’s capacity to implement its strategic plan or strategize sustainability efforts. Coalitions were able to implement new programs, change institutional policies and increase law enforcement efforts on underage drinking on campus and in the community. These efforts lead to statistically significant decreases in a number of indicators of consequences of high-risk drinking. Specifically, after three years of intervention, decreases were found in the intervention schools compared to the control schools in severe consequences due to students’ own drinking and alcohol-related injuries caused to others. In secondary analyses, higher levels of implementation of the intervention were associated with reductions in interpersonal consequences due to others’ drinking and alcohol-related injuries caused to others (Wolfson et al., 2007). Due to these results, the SPARC approach was recommended for use on additional North Carolina colleges campuses by the North Carolina Institute of Medicine (NC IOM) Task Force on Substance Abuse Services (NC IOM, 2009).

CONCLUSIONS

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample size is small, consisting of three waves of qualitative data from eight community organizers. The goal was to describe the process in which community organizers on college campuses engaged the campus and community. As a result, a theoretical model describing this authentic process was developed and its use in practice was confirmed. However, future studies should consider examining other perspectives in process implementation. For example, interviewing coalition members, students, and administrators would provide broad perspective on the process of community organizing.

Findings from this study have implications for understanding community organizing on university campuses and the surrounding community. Although various models of community organizing and community building exist, this analysis documented community organizing within a university setting, a topic that has not been well-documented in the literature. Practitioners using community organizing or similar intervention strategies could replicate or adapt this model to promote change in their community. In addition, it provides a springboard for future research in community organizing on college campuses, such as network analyses to document the relationships between various campus and community stakeholders that are required to create and maintain successful coalitions.

Contributor Information

Kimberly G. Wagoner, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University School of Medicine (WFUSM), Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1063. kwagoner@wfubmc.edu; Telephone: 336/713.4223; Facsimile: 336/716.7554.

Scott D. Rhodes, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University School of Medicine (WFUSM), Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1063. srhodes@wfubmc.edu.

Ashley W. Lentz, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Division of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University School of Medicine (WFUSM), Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1063. awlentz@wfubmc.edu.

Mark Wolfson, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Division of Public Health Sciences, WFUSM, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, NC 27157-1063. mwolfson@wfubmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- Adelman C. Uttering, muttering: Collecting, using and reporting talk for social and educational research. London: Grant McIntyre; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MP, Zakocs RC, Earp JA, French E. Community coalition project directors: what makes them effective leaders? Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2006;12(2):201–209. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200603000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alinsky SD. The poor and the powerful. International Journal of Psychiatry. 1967;4(4):304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson R. The life story interview. London: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Blaine TM, Forster JL, Hennrikus D, O'Neil S, Wolfson M, Pham H. Creating tobacco control policy at the local level: implementation of a direct action organizing approach. Health Education and Behavior. 1997;24(5):640–651. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracht N, Kingsbury L. A five-stage community organization model for health promotion: Empowerment and partnership strategies. In: Bracht N, editor. Health promotion at the community level: New Advances. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. pp. 83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RL, Murphy F, Lythcott N, Blumenthal DS. Community organization and development for health promotion within an urban black community: A conceptual model. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;2(5):56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfoss F, Kegler M. Toward comprehensive understanding of community coalitions: Moving from theory to practice. In: DiClimente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 157–193. [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle A, Wagner E, Walls M, Diehr P, Bell M, Anderman C, McBride C, Catalano RF, Pettigrew E, Simmons R, Neckerman H. The effect of neighborhood-based community organizing: results from the Seattle Minority Youth Health Project. Health Services Research. 2001;36(4):671–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry DJ, Shefner J. Addressing barriers to university-community collaboration: organizing by experts or organizing the experts? Journal of Community Practice. 2004;12(3/4):219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell CE, Littleton MA, Greene PG, Pulley L, Brownstein JN, Sanderson BK, Stalker VG, Matson-Koffman D, Struempler B, Raczynski JM. A Community Health Advisor Program to reduce cardiovascular risk among rural African-American women. [Advance Access published on December 1, 2008];Health Education Research. 2008 doi: 10.1093/her/cyn063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Langford LM. A typology for campus-based alcohol prevention: moving toward environmental management strategies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl. 14):140–147. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing M, Riess TH, Vernon K, Mulia N, Hollinquest M, McKnight C, Jarlais DC, Edlin BR. What's community got to do with it? Implementation models of syringe exchange programs. AIDS Education Prevention. 2005;17(1):68–78. doi: 10.1521/aeap.17.1.68.58688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Moore KS, Rhodes SD, Griffith DM, Allison L, Shirah K, Mebane E. Insiders and outsiders assess who is "the community": Participant observation, key informant interview, focus group interview, and community forum. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker E, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freyder PJ, O’Toole TP. Principle 2: The relationship between partners is characterized by mutual trust, respect, genuineness and commitment. Partnership Perspectives. 2000;1(2):19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt TL, Kaphingst K, DeJong W. A campus-community coalition to control alcohol-related problems off campus: An environmental management case study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):211–215. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DL, O'Reilly K, Tashima N, Crain C, Beeker C, Goldbaum G, Elifson CS, Galavotti C, Guenther-Grey C. Using formative research to lay the foundation for community level HIV prevention efforts: an example from the AIDS Community Demonstration Projects. Public Health Reports. 1996;111(Suppl. 1):28–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kegler MC, Wyatt VH. A multiple case study of neighborhood partnerships for positive youth development. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(2):156–159. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton MA, Cornell CE, Dignan M, Brownstein N, Raczynski JM, Stalker V, McDuffie K, Greene PG, Sanderson B, Streumpler B. Lessons learned from the Uniontown Community Health Project. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2002;26(1):34–42. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight J. Regenerating community. Social Policy. 1987:54–58. [Google Scholar]

- McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzel C, D'Afflitti J. Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance and potential. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(4):557–574. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving health through community organization and community building: a health education perspective. In: Minkler M, editor. Community organizing and community building for health. 2nd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. pp. 30–50. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U.S. colleges. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Weitzman ER, Wechsler H. The effect of a campus-community environmental alcohol prevention initiative on student drinking and driving: results from the "a matter of degree" program evaluation. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2005;6(4):323–330. doi: 10.1080/15389580500253778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Institute of Medicine. Building a Recovery- Oriented System of Care: A Report of the NCIOM Task Force on Substance Abuse Services. Mooresville, NC: North Carolina Institute of Medicine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nyswander DB. Education for health: some principles and their application. Health Education Monographs. 1956;14:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Presley CA, Meilman PW, Lyerla R. Development of the Core Alcohol and Drug Survey: initial findings and future directions. Journal of American College Health. 1994;42:248–255. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9936356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J. Changing women: the narrative construction of personal change through community health work among women in Mexico. Health Education Behavior. 1999;26(1):25–42. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Benfield D. Community-based participatory research: An introduction for the clinician researcher. In: Blessing JD, editor. Physician assistant's guide to research and medical literature. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 2006. pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Rietmeijer CA, Kane MS, Simons PZ, Corby NH, Wolitski RJ, Higgins DL, Judson FN, Cohn DL. Increasing the use of bleach and condoms among injecting drug users in Denver: outcomes of a targeted, community-level HIV prevention program. AIDS. 1996;10(3):291–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J. Approaches to community intervention. In: Rothman J, Erlich JL, Tropman JE, editors. Strategies of community intervention. Itasca, Ill: Peacock Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman J, Tropman JE. Models of community organization and macro practice: Their mixing and phasing. In: Cox FM, Erlich JL, Rothman J, Tropman JE, editors. Strategies of community organization. Itasca, Ill: Peacock Publishers; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan BE, Colthurst T, Segars L. College alcohol risk assessment guide: environmental approaches to prevention. 2008 Retrieved July 11, 2008 from http://www.higheredcenter.org/files/product/cara.pdf.

- Seidman I. Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education and social sciences. New York, NY: Teacher's College Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre AJ, Hylton JB, Johnson LM, Houston C, Witt M, Jacobson L, Ostrow D. Recruiting minority men who have sex with men for HIV research: results from a 4-city campaign. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(6):1020–1027. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Fabian LA. Influencing alcohol control policies and practices at community festivals. Journal of Drug Education. 2006;36(1):15–32. doi: 10.2190/3AT5-8CGB-9Y55-Y4B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey TL, Wagenaar AC. Environmental policies to reduce college drinking: options and research findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl. 14):193–205. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Murray DM, Gehan JP, Wolfson M, Forster JL, Toomey TL, Perry CL, Jones-Webb R. Communities mobilizing for change on alcohol: outcomes from a randomized community trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(1):85–94. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Kelley K, Weitzman ER, SanGiovanni JP, Seibring M. What colleges are doing about student binge drinking: A survey of college administrators. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):219–226. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson M, DuRant RH, Champion H, Ip E, McCoy T, O’Brien MC, Rhodes SD, Sutfin EL, Martin BA, Wagoner K. Impact of a group-randomized trial to reduce high-risk drinking by college students; Chicago, IL. Poster presentation at the 30th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism.Jul, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zakocs RC, Tiwari R, Vehige T, DeJong W. Roles of organizers and champions in building campus-community prevention partnerships. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57(2):233–241. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.2.233-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]