Abstract

Asian American parenting is often portrayed as highly controlling and even harsh. This study empirically tested the associations between a set of recently developed Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures and several commonly used Western parenting measures to accurately describe Asian American family processes, specifically those of Korean Americans. The results show a much nuanced and detailed picture of Korean American parenting as a blend of Western authoritative and authoritarian styles with positive and—although very limited—negative parenting. Certain aspects of ga-jung-kyo-yuk are positively associated with authoritative style or authoritarian style, or even with both of them simultaneously. They were positively associated with positive parenting (warmth, acceptance, and communication) but not with harsh parenting (rejection and negative discipline). Exceptions to this general pattern were Korean traditional disciplinary practices and the later age of separate sleeping of children. The study discusses implications of these findings and provides suggestions for future research.

Keywords: Korean American parenting, Western parenting, family processes

Empirical research on Asian American1 families often paints a complex and paradoxical picture. For example, studies about family processes and youth outcomes among Asian Americans often do not align with conventional patterns (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Park, Kim, Chiang, & Ju, 2010). In general, authoritative parenting, a firm and warm style, is connected to intimate parent-child relations and positive child outcomes. Authoritarian parenting, characterized by strict and restrictive parental control and lack of warmth, is associated with higher parent-child conflict, negative youth behaviors, and poor mental health (Baumrind, 1991). Asian American parents usually endorse and practice strict control and are regarded to be less expressive in showing affection (Huntsinger, Jose, Rudden, Luo, & Krieg, 2001). However, their seemingly authoritarian parenting is not always related to negative youth outcomes as it is in European American families (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Deater-Deckard, Dodge, & Sorbring, 2005). In fact, in Asian American families, strict control tends to predict improved outcomes such as higher school grades (Steinberg, Lamborn, Darling, Mounts, & Dornbusch, 1994). Therefore, the existing family process model (e.g., conceptualizing parenting style as authoritarian and authoritative), which is derived mainly from a Western culture and empirical evidence from non-Hispanic white families, seems inadequate in understanding Asian family processes (Choi, Harachi, Gillmore, & Catalano, 2005; Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts, & Fraleigh, 1987).

Culture and Parenting

The culture and social environments in which families reside help determine parental beliefs about childrearing goals and parenting methods, which subsequently shape actual parenting behaviors and parent-child relationships (Harkness & Super, 2002; Rubin & Chung, 2006). Thus, parenting goals, values, and practices and parent-child interactions vary from culture to culture (Bornstein & Cote, 2006; Deater-Deckard et al., 2011). For example, in the dominant Western culture in the United States, the desired childrearing goals are independence, individualism, social assertiveness, confidence, and competence (Rubin & Chung, 2006). Authoritative parenting style is regarded as the most ideal to promote these core values. Specifically, authoritative parenting establishes firm and clear rules but employs inductive reasoning and expressive warmth and allows autonomy, active exploration, and risk-taking, yielding positive youth outcomes (Rubin & Chung, 2006). It also helps to build close parent-child relationships and reduce parent-child conflict, and it has been shown to be the most beneficial in all domains of youth outcomes concerning academic performance, externalizing behaviors, and mental health (Park, et al., 2010).

Conversely, traditional Asian families tend to be culturally collectivistic, emphasizing interdependence, conformity, emotional self-control, and humility.2 This is in stark contrast to the core values of the Western culture (Kurasaki, Okazaki, & Sue, 2002).3 These Asian cultural values produce deeply ingrained family values, such as a strong sense of obligation and orientation to the family and respect for and obedience to parents and elders (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Fuligni, 2007). Despite the differences between Western and Asian family processes, the practice of using Western parenting theories to explain Asian parenting dominates the existing family and parenting research. Similarly, Asian American families, despite their cultural difference to the dominant Western culture in the U.S., are often evaluated using the Western paradigm. It is likely that incorrectly fitting one culture into another's framework and the failure to capture the critical differences in core family values and practices has led to the complex and even paradoxical findings concerning Asian American families in parenting research.

Asian American Parenting Measures

Western theories of parenting tend to label Asian American parenting as more controlling than the idealized authoritative parenting (Kagitçibasi, 2007; Vinden, 2001). However, a more nuanced conceptualization sees Asian American parenting, though more directive and restrictive than its Western counterpart, as a style that is practiced with reasoning as well as warmth (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Kagitçibasi, 2007). In recent years, several measures have been created to assess family processes unique to Asian Americans. For example, the guan parenting and qin measures were created for Chinese Americans (Chao, 1994; Wu & Chao, 2011). Guan parenting (translated as “to govern/train and love”) involves directive control and close monitoring of child behaviors while building close parent-child relationships. Qin (translated as “child's feeling of closeness to parents or parental benevolence”) captures Asian expressions of love for their children. The qin measures ask children's perceptions of parental devotion, sacrifice, thoughtfulness, and guan. The rationale is that Asian American parents' affection is conveyed through instrumental support, devotion, close monitoring, and support for education, rather than through physical, verbal, and emotional expressions such as hugging, kissing, and praising, which are typical indicators of Western parental warmth (Wu & Chao, 2011). The guan ideology and behaviors and the qin measures are excellent examples of Asian American family processes in which components of both authoritarian and authoritative styles emerge in an idealized Asian parenting practice.

In a similar endeavor to develop indigenous parenting measures, several scales have been recently developed to capture family processes that are specific to Korean American families, called ga-jung-kyo-yuk ( ). Several scales that collectively assess ga-jung-kyo-yuk were generated using multiple methods, including focus groups, an extensive literature review, and reviews by academic experts and community leaders. With a survey data, they have been tested for psychometric properties and shown to be reliable and valid for Korean American parents (See for more details, Choi & Kim, 2010; Choi, Kim, Drankus, & Kim, 2012). Ga-jung-kyo-yuk (translated as “home [or family] education”) is closest in concept to “family socialization” or “family processes.” Although family processes and/or socialization and ga-jung-kyo-yuk similarly describe the process of socializing children to a set of core norms, beliefs, and values through parenting, main differences exist in the specifics of those norms, beliefs, and values. The core values of ga-jung-kyo-yuk include emphasis on parenting via role-modeling, the centrality of the family, family hierarchy, demonstration of respect for and the use of appropriate etiquette with parents and the elderly, age veneration, and family obligations and ties. For example, three new measures—Korean traditional parent virtues, enculturation4 of familial and cultural values, and important Korean traditional etiquette—are specific dimensions that exemplify core ga-jung-kyo-yuk values.

). Several scales that collectively assess ga-jung-kyo-yuk were generated using multiple methods, including focus groups, an extensive literature review, and reviews by academic experts and community leaders. With a survey data, they have been tested for psychometric properties and shown to be reliable and valid for Korean American parents (See for more details, Choi & Kim, 2010; Choi, Kim, Drankus, & Kim, 2012). Ga-jung-kyo-yuk (translated as “home [or family] education”) is closest in concept to “family socialization” or “family processes.” Although family processes and/or socialization and ga-jung-kyo-yuk similarly describe the process of socializing children to a set of core norms, beliefs, and values through parenting, main differences exist in the specifics of those norms, beliefs, and values. The core values of ga-jung-kyo-yuk include emphasis on parenting via role-modeling, the centrality of the family, family hierarchy, demonstration of respect for and the use of appropriate etiquette with parents and the elderly, age veneration, and family obligations and ties. For example, three new measures—Korean traditional parent virtues, enculturation4 of familial and cultural values, and important Korean traditional etiquette—are specific dimensions that exemplify core ga-jung-kyo-yuk values.

Ga-jung-kyo-yuk also includes childrearing practices. For example, more than 80% of Korean immigrant parents reported practicing a traditional sleeping arrangement, that is, co-sleeping with their child until he or she was 6 years old, on average (Choi, et al., 2012). The goal of co-sleeping with an infant or young child in Asian cultures is to build a close parent-child bond, reflecting a cultural emphasis on interdependence (Greenfield & Cocking, 1994) and is likely another example of a nonverbal expression of parental love. In addition, although similar practices that involve corporal punishment are found in other cultures, three physical disciplinary practices primarily used with young children (i.e., hitting their palms with a stick, hitting the calf of their leg with a stick, and having them raise their arms for a prolonged time) are identified as a traditional Korean parenting practice (e.g., Choi & Kim, 2010; E. Kim & Hong, 2007). These forms of discipline are practiced along with parental love in the cultural context that stern parenting is an ideal virtue in traditional ga-jung-kyo-yuk (K. Kim, 2006). Thus, similar to guan and qin among Chinese Americans, several aspects of both authoritative and authoritarian parenting style seem to coexist in ga-jung-kyo-yuk among Korean American families.

Relationships between Asian American and Western Parenting

Despite a significant stride made in research on Asian American parenting in recent years, there is a continued lack of empirical evidence on how Asian and Western family processes are different from or similar to one another. Subgroup level understanding is lacking even more, with Chinese Americans being the exception. Filling in the knowledge gap are stereotypes, prejudices, and misperceptions. The controversy over “tiger moms” (Chua, 2011) showcases the lack of understanding of Asian American family processes and parenting styles. The premise that Asian American parents are utterly controlling, demanding, emotionally insensitive, and harsh, but that they effectively churn out math and music prodigies, is, quite simply, an exaggeration. For example, even if Asian American parents, more than European American parents on average, expect their child to conform to parental rules and expectations, does such a parenting style necessarily translate to a lack of parental warmth and acceptance and poor parent-child communication, as well as high levels of parental rejection and harsh discipline? This study aims to answer this question by empirically examining how culturally distinct Asian American parenting values and practices are related to Western parenting styles and behaviors. Specifically, this study investigates whether and how the Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures, both of parenting values and behaviors, are related to several widely used Western parenting measures, including parenting styles (authoritarian and authoritative), positive parenting practices (parental warmth, acceptance, monitoring, and parent-child communication) and harsh parenting practices (negative discipline and parental rejection).

Following the notion that ideal Asian American parenting is a unique combination of authoritarian and authoritative styles, this study hypothesizes that the ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures are positively associated with both authoritarian and authoritative Western parenting styles. This study further hypothesizes that the ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures are positively associated with several characteristics of authoritative parenting style (parental acceptance, warmth, and monitoring behaviors, as well as parent-child communication), but are negatively associated with the measures of harsh parenting such as negative discipline (e.g., getting angry, slapping or hitting with hand, fist, or object) and parental rejection (e.g., resenting or paying no attention to the child). Although certain aspects of Asian American parenting, such as a high level of parental control, may seem authoritarian, the ideal Asian American parental control is not coercive, punitive, or rejecting (Kagitçibasi, 2007). In addition, although the cultural norms such as family hierarchy and age veneration may not be a subject of negotiation with children and thus likely require strict rules, the ultimate goals of establishing and building strong family ties and interdependence in the family are likely to discourage a harsh and rejecting parenting style.

More complex associations are expected with traditional Korean disciplinary practices. Although corporal punishment, these disciplinary practices, at least in Korean culture, are differentiated from harsh parenting and parental rejection and widely accepted as legitimate methods of discipline because rules about these practices are set in advance and to be used without parental impulsiveness (E. Kim & Hong, 2007). Thus, the use of these particular practices is expected to be positively related to both authoritarian and authoritative styles and positively associated with several positive parenting measures. However, Korean immigrant families in the U. S. reside in a society in which corporal punishment is strongly discouraged with possible legal complications. In fact, these parents, although they may have used one of these methods at some point, did not use them frequently (Choi, et al., 2012). Thus, the continued use of these physical disciplinary practices despite the social and possibly legal ramifications is likely to be positively associated with harsh parenting in an American context.

As reflected in the low use of traditional disciplinary practices, immigrants and their offspring, even if reluctantly and slowly, alter their culture, including parenting values and behaviors, through the process of acculturation (Berry, 1997; Ward, 1996). In other words, parenting values and behaviors may change as immigrant parents adapt to the mainstream culture. For example, a higher level of acculturation may predict a higher use of Western parenting styles. Thus, this study examines whether the relationships between Korean American parenting measures and Western parenting measures remain the same after taking parental acculturation into account. If the relationships remain unchanged after accounting for parental acculturation and enculturation, it would indicate that it is not parental acculturation that explains, for example, coexistence of authoritative and authoritarian parenting.

This study seeks to further advance our understanding by examining these relationships among mothers and fathers. Fathers are rarely included in family surveys, so we know much less about paternal than maternal parenting. There are significant and meaningful differences in how fathers and mothers view parenting, how they interact with their children, and how acculturation influences their parenting choices. Children also perceive similar behaviors of mothers and fathers differently. For example, childrearing is usually regarded mainly as mother's responsibility in Korean culture (E. Kim, 2005), paternal and maternal report of conflict had differential effects on youth depression (De Ross, Marrinan, Schattner, & Gullone, 1999), and only maternal acculturation moderated parenting (E. Kim, Cain, & McCubbin, 2006).

In sum, we hypothesize that the Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures will be (1) positively associated both with authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles; (2) positively associated with positive Western parenting characteristics (e.g., parental warmth, parent-child communication, and monitoring), and (3) negatively associated with harsh parenting (e.g., negative discipline and parental rejection). One exception for these hypotheses is with the Korean traditional disciplinary practices, which we believe will positively relate to both positive and harsh parenting. The maternal and paternal differences in the hypotheses of this study are exploratory. There is very limited information from which to generate a set of explicit hypotheses in regard to parent-gender differences. One possible expectation would be that because Korean immigrant mothers are more involved in parenting and are more expressive in affection than are Korean immigrant fathers (Choi & Kim, 2010), the mother's use of Korean traditional disciplinary practices may not be positively associated with Western harsh parenting as much as that of the father's.

Method

Overview of the Project

The data are from the Korean American Families (KAF) Project, a survey of Korean American youth and their parents living in the Chicago metropolitan area, collected over a two-year period. The family was the sampling unit. Korean immigrant families with early adolescents (aged 11–14 years) were eligible to participate in surveys administered by bilingual interviewers. In 2007, 291 families were interviewed (220 youth, 272 mothers and 164 fathers; N = 656).5 A follow-up interview was completed a year later at the end of 2008 with 247 families (220 youth, 239 mothers and 146 fathers; N = 605). Parents were provided $40 and youth $20 for their participation. Three sources (phonebooks, public school rosters, and Korean church or temple rosters) were used to recruit survey participants. About an equal number of families were sampled from each data source, and families did not statistically differ in age, gender, and sociodemographics across sources. However, there were two statistically significant differences in the main study constructs by the sampling source. Specifically, school roster–based participants reported a higher endorsement of Korean traditional etiquette (F = 3.837; p < .05) and a higher use of negative forms of discipline (F = 4.489; p < .05) than did church or temple roster–based participants. Sample sources are controlled in the later analyses to account for these differences.

Survey was available in Korean and English. Survey items for parents were first developed in Korean and youth items in English. Translations of survey questionnaires went through numerous iterations and back-translations and several pretests were conducted with parents and youth. All parents except one filled out the Korean version while most of youth filled out the English one.

Sample Characteristics

At the time of the first survey, average ages were 12.97 years (SD = 1.00) for youth, 43.4 years for mothers (SD = 4.57) and 46.3 years for fathers (SD = 4.69). This study used only the parent data from the first survey. The level of parental education was high: 63.7% of mothers and 70.3% of fathers reported having at least some college education, either in Korea or in the U. S. All parents were born in Korea and the average number of years of living in the U.S. was 15.44 (S.D. = 8.36). Sixty-one percent of their children were born in the U.S., having lived in the U.S. for 10.44 years on average (S.D. = 4.14). About 47% reported an annual household income between $50,000 and $99,999, while 8% less than $25,000, 23.6% between $25,000 and $49,999, and 22% over $100,000. A total of 21% of mothers reported having received public assistance, food stamps, or qualifying for the free or reduced-price school lunch programs, while 15% were currently receiving these programs. Overall, the characteristics of the sample were similar to the socioeconomic characteristics of Korean parents in the U.S., that is, urban middle-class immigrants with a high proportion being small-business owners (40% of fathers), protestant (77%) (Min, 2006), and fairly comparable to the parent profile in national data sets (such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health).

Measures

Reliability coefficients (Cronbach α) were examined across mothers, fathers, and the full sample of parents. In addition, unless noted, response options for each item were on a Likert scale from 1 (e.g., never or strongly disagree) to 5 (e.g., almost always or strongly agree).

Korean Ga-jung-kyo-yuk Constructs

Korean traditional parent virtues

Six items assess Korean traditional parenting beliefs including parental virtues and filial piety. Example items include “Parents should try to demonstrate proper attitude and behavior to their children” and “Parents should teach their children to respect elders by showing that they love and respect their parents (i.e., children's grandparents).” Reliability coefficients ranged from .86 to .90.

Enculturation of familial and cultural values

Seven items ask parents about important traditional values that they want to transmit to their children. Items include supporting siblings or relatives in need of help, regarding family as a source of trust and dependence, doing things to please parents, taking care of parents when they get older, maintaining close contact with family no matter where they live, and seriously considering parents' wishes and advice in career or marriage decisions. Reliability coefficients ranged from .73 to .79.

Important Korean traditional etiquette

There are several rules in Korean traditional etiquette that reflect core Korean social traditions and norms. Six items asked parents how important it is for specific behavioral etiquette to be practiced by their child. Examples include “My child properly greets adults (e.g., bowing to adults with proper greetings)” and “My child uses formal (respectful) speech to adults.” Reliability coefficients ranged from .90 to .93.

Co-sleeping and age of separate sleeping

The survey asked parents whether their child slept with them during the toddler and early elementary school years. Response options were “Yes” and “No.” No reliability was estimated since it was a binary variable. If the response was yes, parents were asked to specify at which age the child started sleeping in his or her own room.

Korean traditional disciplinary practices with young children

Parents were asked whether they used practices such as hitting a child's palms with a stick, hitting a child's calf with a stick, or having a child raise his/her arms for a prolonged time as punishment when their child was preteen. Although over 80% of parents reported that they have used one of three methods, correlations among the items were quite low, indicating that each practice may be used but not as a cluster of practices. Thus, a composite scale using these items seemed inappropriate. Accordingly, the responses were coded either as 0 for no use of the specified disciplinary practices or 1 for use of any practices. No reliability was estimated since it is a binary variable.

Western Parenting Constructs

Authoritarian parenting style

Seven items were used to assess authoritarian parenting style from the Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ, Buri, 1991). The PAQ was constructed to measure Baumrind's four parenting styles. Examples of items for the authoritarian style include “It is for my child's good to be forced to conform to what I thought was right, even if my child doesn't agree with me” and “I do not allow my child to question any decision I make.” Reliability coefficients ranged from .64 to .73.

Authoritative parenting style

Five items from the PAQ (Buri, 1991) measured authoritative parenting style. Examples include “When family policy [rule] is established, I discuss the reasoning behind the policy with my child” and “I take my child's opinion into consideration when making family decisions but I would not decide for something simply because my child wants it.” Reliability coefficients ranged from .66 to .75.

Parental warmth

Seven items from the Parenting Practices Questionnaire (PPQ, Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 1995) assessed parental expression of affection, sympathy, and responsiveness toward their children. Examples include “I express affection by hugging and holding my child” and “I give comfort and understanding when my child is upset.” Reliability coefficients ranged from .85 to .89.

Parental acceptance

Nine items from a short version of the Parental Acceptance and Rejection Scales (PARS, Rohner, 2004) were used to assess parents' caring, attentive, and comforting behaviors (such as saying nice things to my child, making it easy for my child to tell things that are important, and paying a lot of attention). Reliability coefficients ranged from .87 to .89.

Parental monitoring

A total of eight items were adopted from several sources to cover a range of monitoring behaviors of parents. The sources include the Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) Project and the Pittsburgh Youth Study (PYS). Items asked parental monitoring on child's whereabouts, friends and their parents, free time, money management, and after-school activities. One example is, “When your child is away from home, how often do you know where s/he was and who s/he was with?” Reliability coefficients ranged from .85 to .90.

Parent-child communications

Six items from the LIFT and the PYS assessed how parents and children communicate in the family. Examples include “Is your child free to say what s/he thinks in your family?” and “Do you find it easy to discuss problems with your child?” Reliability coefficients ranged from .79 to .86.

Parental negative discipline

Six items from the LIFT assessed a range of negative disciplinary behaviors by parents, such as raising one's voice; giving a disapproving look to child; restricting privileges; slapping or hitting with hand, fist or object; spanking; and getting angry. Reliability coefficients ranged from .78 to .85.

Parental rejection

Fifteen items also adopted from a short version of PARS (Rohner, 2004) assessed how much parent rejects child, for example, resenting a child, hurting a child's feelings, and paying no attention to a child. Reliability coefficients ranged from .77 to .79.

Control Variables

Several control variables include the sampling sources (dummy-coded, phone-based sampling as a reference) and demographic variables (age, gender, income, and education of parents as well as youth age and gender). Gender was dummy-coded with mothers and girls as a reference. In addition, parental acculturation is adjusted as controls. Acculturation is a multidimensional and multifaceted construct. Thus, several measures were used to assess parents' level of adapting to the mainstream culture as well as their level of maintaining their culture of origin. Specifically, the number of years living in the U.S., English-language competence, engagement in social and cultural activities of the mainstream (i.e., reading, music, media use, foods, social clubs, and holidays), and a sense of American identity were used to indicate the level of acculturation among parents. Parallel to the acculturation items, parents' engagement in the culture of origin and a sense of Korean identity were also included. These measures were adapted from the language, identity, and behavior (LIB) measure (Birman & Trickett, 2002). All these measures showed high internal consistency with the sample. (Details on acculturation items are available from the first author.)

Analysis Plan

We first examined descriptive statistics of main constructs, including bivariate correlations and means and standard deviations for continuous variables or proportions for binary variables. We used the full sample of parents and also for mothers and fathers separately. Second, to examine the associations between Korean and Western parenting measures, we used hierarchical multivariate regression analyses with Korean parenting constructs as independent variables and Western parenting constructs as dependent variables. The decision to model the Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk construct as an independent variable is not to imply a causal or a predicting relationship in which one precedes the other. Multivariate regressions enable simultaneous modeling of the ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures (reflecting the reality in which these values and behaviors are likely to be practiced together) in testing their associations with Western parenting. The Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk constructs together were regressed on each of Western parenting measures individually while not accounting for any controls (step 1), resulting in eight regressions. In step 2, we examined the associations after accounting for sampling source and demographic controls. In step 3, we added several parental acculturation variables. In steps 2 and 3, to examine whether the associations differed by parental gender, we created interaction terms (the product term of independent variables by parental gender) and entered them into the regression models. When interactions were statistically significant, we used simple slope analyses (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003) and graphically plotted slopes to visualize the relationships by mothers and fathers. There were missing responses in the survey, ranging from 5% to 10 % depending on the regression models. The analyses were conducted using multiple imputations (MI) method (Schafer & Graham, 2002). We used STATA/SE (v. 11.1) for the analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Descriptive statistics of the main study constructs are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 reports means and proportions for fathers and mothers. We examined the differences by gender in means or proportions using independent t-test or χ2 statistics. Mothers reported higher rates than fathers in Korean traditional parent virtues, parental warmth, acceptance, monitoring, and parent-child communication, as well as Korean traditional disciplinary practices. Table 2 shows correlations among the study constructs. One notable finding is that authoritarian parenting style is positively correlated with authoritative parenting style in both mothers and fathers. We explicitly examined the statistical differences by gender on the associations among constructs in the subsequent regression analyses by testing interaction terms.

Table 1.

Means or proportions (%) of the study constructs by mothers and fathers

| Mean or proportion (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Constructs | Mothers | Fathers |

| N | 272 | 164 |

| Korean traditional parent virtues | 4.64 (0.44) | 4.53 (0.52)* |

| Enculturation of familial cultural values | 4.24 (0.40) | 4.20 (0.40) |

| Important Korean traditional etiquettes | 4.44 (0.64) | 4.45 (0.67) |

| Co-sleeping | 82% | 81% |

| Age of separate sleeping | 6.69 (4.47) | 5.97 (4.11) |

| Korean traditional disciplinary practices | 86% | 76%* |

| Authoritarian parenting style | 2.66 (0.58) | 2.70 (0.57) |

| Authoritative parenting style | 3.84 (0.53) | 3.73 (0.60) |

| Parental warmth | 4.13 (0.63) | 3.89 (0.70)*** |

| Parental acceptance | 4.19 (0.54) | 3.97 (0.63)*** |

| Parental monitoring | 4.26 (0.49) | 3.85 (0.66)*** |

| Parent-child communication | 3.89 (0.66) | 3.57 (0.69)*** |

| Parental rejection | 1.55 (0.34) | 1.54 (0.37) |

| Parental negative discipline | 2.27 (0.66) | 2.16 (0.64) |

Note: Sample sizes slightly vary depending on the construct (i.e. 269 to 272 for mothers and 161 to 164 for fathers). Since missing was none to very low per construct, only the sample sizes of complete cases for mothers and fathers are reported here.

Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations.

The statistical differences were tested using independent sample t-test for continuous variables and χ2 for dichotomous variables.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Table 2.

Correlations among the main constructs

| Construct | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Korean parent virtues | -- | 0.352** | 0.292** | 0.201* | 0.084 | −0.100 | 0.145 | 0.427** | 0.362** | 0.415** | 0.280** | 0.385** | −0.035 | 0.045 |

| 2 | Enculturation | 0.367** | -- | 0.339** | 0.095 | 0.110 | 0.020 | 0.183* | 0.298** | 0.295** | 0.341** | 0.099 | 0.134 | 0.026 | 0.139 |

| 3 | Korean etiquettes | 0.185** | 0.241** | -- | 0.075 | 0.134 | 0.011 | 0.226** | 0.250** | 0.123 | 0.157* | 0.022 | 0.130 | 0.089 | 0.195* |

| 4 | Co-sleeping | −0.001 | 0.049 | 0.213** | -- | 0.694** | −0.076 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.067 | 0.094 | 0.045 | 0.105 | 0.027 | −0.030 |

| 5 | Age of separate sleeping | 0.025 | 0.077 | 0.154* | 0.699** | -- | −0.059 | 0.090 | 0.031 | 0.062 | 0.074 | 0.087 | 0.047 | 0.064 | 0.022 |

| 6 | Traditional discipline | −0.099 | −0.040 | 0.091 | 0.203** | 0.204** | -- | 0.161* | −0.172* | −0.041 | −0.085 | 0.037 | 0.017 | 0.113 | 0.313** |

| 7 | Authoritarian style | 0.016 | 0.059 | 0.218** | 0.125* | 0.143* | 0.180** | -- | 0.195* | 0.081 | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.228** | 0.436** |

| 8 | Authoritative style | 0.280** | 0.283** | 0.162** | −0.053 | −0.052 | −0.013 | 0.140* | -- | 0.480** | 0.514** | 0.240** | 0.452** | −0.174* | 0.029 |

| 9 | Parental warmth | 0.286** | 0.367** | 0.114 | −0.080 | −0.025 | −0.151* | −0.013 | 0.389** | -- | 0.718** | 0.409** | 0.579** | −0.365** | −0.093 |

| 10 | Parental acceptance | 0.302** | 0.345** | 0.241** | −0.015 | −0.024 | −0.108 | −0.015 | 0.443** | 0.659** | -- | 0.406** | 0.592** | −0.485** | −0.139 |

| 11 | Parental monitoring | 0.282** | 0.122* | 0.142* | −0.066 | −0.071 | −0.202** | −0.052 | 0.183** | 0.311** | 0.400** | -- | 0.567** | −0.314** | −0.051 |

| 12 | Communication | 0.259** | 0.245** | 0.128* | −0.021 | −0.020 | −0.121* | −0.032 | 0.377** | 0.449** | 0.565** | 0.521** | -- | −0.323** | −0.058 |

| 13 | Parental rejection | −0.106 | −0.064 | −0.096 | 0.100 | 0.085 | 0.202** | 0.297** | −0.151* | −0.377** | −0.373** | −0.276** | −0.303** | -- | 0.585** |

| 14 | Negative discipline | 0.058 | 0.070 | 0.033 | 0.167** | 0.209** | 0.288** | 0.402** | 0.033 | −0.164** | −0.172** | −0.119 | −0.154* | 0.602** | -- |

Note: Correlations below the diagonal are for mothers; those above are for fathers.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Hierarchical Regression Models

The results on the regressions in steps 1–3 were quite similar in terms of the size of coefficients and statistical significance. In other words, the associations between Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk and Western parenting measures did not change when demographic characteristics and parental acculturation variables were accounted for. The results from the final model (step 3) are described in Tables 3 and 4, which are summarized in such a way that the top of the rows shows coefficients from the main effect models (without interactions) and the bottom of the rows show only interaction coefficients from the models with interaction product terms added.

Table 3.

Associations between ga-jung-kyo-yuk and authoritarian and authoritative styles, parental warmth, and acceptance

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Authoritarian | Authoritative | Warmth | Acceptance | |||||

| N | 431 | 431 | 431 | 431 | ||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Sampling source controls | ||||||||

| School-based sampling | 0.018 | 0.071 | −0.033 | 0.064 | 0.046 | 0.075 | −0.011 | 0.066 |

| Church-based sampling | −0.033 | 0.066 | −0.156* | 0.060 | 0.010 | 0.071 | −0.086 | 0.062 |

| Demographic controls | ||||||||

| Parental income | 0.013 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.027 | 0.032 | 0.031 | 0.010 | 0.027 |

| Parental education | 0.065* | 0.032 | 0.015 | 0.029 | −0.026 | 0.034 | −0.026 | 0.030 |

| Fathers | 0.081 | 0.060 | −0.139* | 0.054 | −0.257*** | 0.064 | −0.254*** | 0.056 |

| Parental age | −0.008 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.013 | 0.007 | 0.017** | 0.006 |

| Boys | −0.039 | 0.055 | 0.035 | 0.050 | −0.058 | 0.058 | −0.015 | 0.051 |

| Youth age | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.037 | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.023 |

| Parental acculturation controls | ||||||||

| Years in US | 0.003 | 0.004 | −0.012** | 0.004 | −0.002 | 0.005 | −0.009* | 0.004 |

| English competence | −0.001 | 0.049 | 0.119** | 0.045 | 0.034 | 0.052 | 0.059 | 0.046 |

| Mainstream culture | −0.035 | 0.052 | 0.087 | 0.047 | 0.212*** | 0.055 | 0.190 | 0.048 |

| American identity | 0.004 | 0.040 | 0.023 | 0.037 | 0.029 | 0.043 | 0.011 | 0.037 |

| Korean culture | 0.175*** | 0.046 | 0.010 | 0.042 | 0.118* | 0.050 | 0.018 | 0.044 |

| Korean identity | −0.100 | 0.045 | 0.044 | 0.041 | −0.013 | 0.048 | 0.028 | 0.042 |

| Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk constructs | ||||||||

| Korean traditional parental virtue | 0.018 | 0.064 | 0.268*** | 0.058 | 0.260*** | 0.068 | 0.255*** | 0.059 |

| Enculturation of familial/cultural values | 0.026 | 0.075 | 0.212** | 0.068 | 0.364*** | 0.079 | 0.297** | 0.069 |

| Korean traditional etiquette | 0.161** | 0.046 | 0.099* | 0.042 | 0.026 | 0.049 | 0.098* | 0.043 |

| Co-sleeping arrangement | −0.022 | 0.098 | −0.159 | 0.089 | −0.118 | 0.104 | −0.016 | 0.091 |

| Age of separate sleeping | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

| Korean traditional disciplinary practices | 0.231** | 0.073 | −0.122 | 0.066 | −0.102 | 0.078 | −0.115 | 0.068 |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender X Korean parental virtue | 0.056 | 0.127 | 0.123 | 0.115 | 0.171 | 0.135 | 0.175 | 0.118 |

| Gender X familial and cultural value | 0.087 | 0.153 | −0.042 | 0.138 | −0.144 | 0.162 | 0.029 | 0.141 |

| Gender X Korean traditional etiquette | 0.002 | 0.091 | 0.037 | 0.083 | −0.005 | 0.097 | −0.113 | 0.085 |

| Gender X co-sleeping | 0.023 | 0.203 | −0.241 | 0.183 | 0.027 | 0.216 | −0.091 | 0.188 |

| Gender X age of separate sleeping | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.011 | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.017 |

| Gender X traditional discipline | −0.020 | 0.145 | −0.242 | 0.131 | 0.078 | 0.154 | 0.010 | 0.134 |

| R2 | 13.51% | 24.76% | 26.70% | 27.85% | ||||

Note: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error.

The top of the rows shows coefficients from the main effect models (without interactions) and the bottom of the rows show only interaction coefficients from the models with interaction product terms added.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

Table 4.

Associations between ga-jung-kyo-yuk and parental monitoring, parent-child communication, parental rejection, and negative discipline

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Monitoring | Communication | Rejection | Negative discipline | |||||

| N | 431 | 431 | 431 | 431 | ||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Sampling source controls | ||||||||

| School-based sampling | 0.082 | 0.076 | −0.002 | 0.081 | −0.020 | 0.045 | 0.034 | 0.078 |

| Church-based sampling | 0.008 | 0.071 | −0.029 | 0.076 | −0.062 | 0.042 | −0.141 | 0.073 |

| Demographic controls | ||||||||

| Parental income | −0.016 | 0.031 | 0.017 | 0.033 | −0.016 | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.032 |

| Parental education | −0.001 | 0.034 | −0.007 | 0.037 | 0.061** | 0.020 | 0.096** | 0.035 |

| Fathers | −0.456*** | 0.064 | −0.347*** | 0.069 | 0.019 | 0.038 | −0.010 | 0.066 |

| Parental age | −0.007 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.008 | −0.007 | 0.004 | −0.024** | 0.007 |

| Boys | −0.062 | 0.059 | −0.064 | 0.063 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.158** | 0.060 |

| Youth age | −0.033 | 0.026 | 0.001 | 0.028 | −0.021 | 0.015 | −0.049 | 0.027 |

| Parental acculturation controls | ||||||||

| Years in US | 0.000 | 0.005 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| English competence | 0.047 | 0.053 | −0.008 | 0.057 | −0.058 | 0.031 | −0.019 | 0.054 |

| Mainstream culture | 0.211 | 0.056 | 0.279*** | 0.060 | 0.044 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.057 |

| American identity | −0.053 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.046 | −0.017 | 0.026 | −0.063 | 0.044 |

| Korean culture | 0.056 | 0.050 | −0.020 | 0.053 | 0.029 | 0.030 | 0.113* | 0.051 |

| Korean identity | 0.026 | 0.049 | 0.065 | 0.052 | −0.041 | 0.029 | −0.022 | 0.050 |

| Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk constructs | ||||||||

| Korean traditional parental virtue | 0.263*** | 0.068 | 0.304*** | 0.073 | −0.063 | 0.041 | 0.005 | 0.070 |

| Enculturation of familial/cultural values | −0.022 | 0.081 | 0.130 | 0.086 | 0.001 | 0.048 | 0.083 | 0.082 |

| Korean traditional etiquette | 0.040 | 0.050 | 0.081 | 0.054 | −0.005 | 0.029 | 0.031 | 0.050 |

| Co-sleeping arrangement | −0.100 | 0.105 | 0.016 | 0.113 | 0.020 | 0.063 | −0.095 | 0.108 |

| Age of separate sleeping | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.022* | 0.009 |

| Korean traditional disciplinary practices | −0.118 | 0.078 | −0.082 | 0.084 | 0.117* | 0.046 | 0.416*** | 0.080 |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender X Korean parental virtue | 0.151 | 0.135 | 0.244 | 0.145 | −0.032 | 0.080 | −0.182 | 0.138 |

| Gender X familial and cultural value | −0.016 | 0.163 | −0.292 | 0.175 | −0.010 | 0.096 | −0.001 | 0.166 |

| Gender X Korean traditional etiquette | −0.158 | 0.099 | −0.002 | 0.106 | 0.149* | 0.058 | 0.245* | 0.099 |

| Gender X co-sleeping | −0.178 | 0.215 | 0.019 | 0.232 | −0.066 | 0.128 | −0.091 | 0.220 |

| Gender X age of separate sleeping | 0.028 | 0.020 | −0.004 | 0.021 | 0.004 | 0.012 | −0.019 | 0.020 |

| Gender X traditional discipline | 0.339* | 0.154 | 0.228 | 0.166 | −0.099 | 0.091 | −0.018 | 0.157 |

| R2 | 24.56% | 22.08% | 8.54% | 21% | ||||

Note: b = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error.

The top of the rows shows coefficients from the main effect models (without interactions) and the bottom of the rows show only interaction coefficients from the models with interaction product terms added.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

Hypotheses 1: Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk will be positively associated with both authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles

The overall pattern of findings seems to support the study hypotheses, although in varying ways, depending on the parenting constructs under examination. Specifically, after accounting for all control variables, Korean disciplinary practices were positively related to authoritarian style, while Korean traditional parental virtue and enculturation of familial/cultural values were positively associated with authoritative style. Korean Traditional etiquette was positively associated both with authoritarian and authoritative styles.

Hypotheses 2: Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk will be positively associated with Western positive parenting characteristics

As hypothesized, Korean traditional parental virtue was positively associated with all positive parenting constructs (warmth, acceptance, monitoring and communication). Enculturation of familial/cultural values was positively associated with warmth and acceptance but not significantly associated with monitoring and communication. Korean traditional etiquette was positively associated only with acceptance. Co-sleeping, age of separate sleeping, and Korean traditional disciplinary practices were not significantly associated with any of the positive parenting constructs.

Hypotheses 3: Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk will be negatively associated with Western harsh parenting

Traditional parental virtue, enculturation, traditional etiquette, and co-sleeping were not associated with harsh parenting, which includes parental rejection and negative discipline. Age of separate sleeping, unexpectedly, was positively related to negative discipline. Traditional disciplinary practices were positively associated with the Western harsh parenting, as hypothesized.

Testing the Associations by Mothers and Fathers

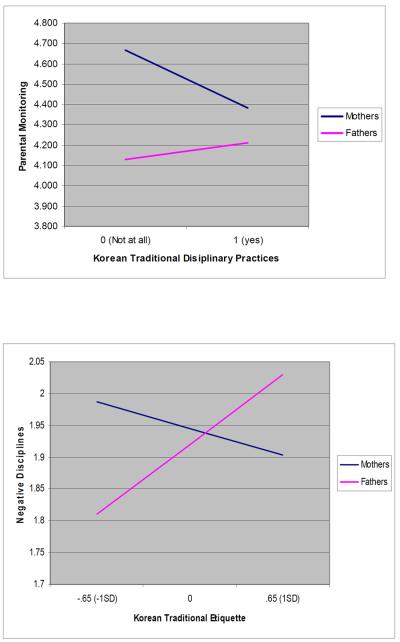

The majority of interactions were not statistically significant, revealing that the associations between Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk and Western parenting measures are largely similar across mothers and fathers. Three interaction terms were statistically significant: the relationships between traditional disciplinary practices and monitoring, traditional etiquette and rejection, and traditional etiquette and negative disciplines. Simple slope analyses show that mothers who used traditional disciplinary practices were significantly less likely to practice monitoring (b = −0.280; p < .05), while this relationship was not significant among fathers. Although the interaction term was significant, the relationship between traditional etiquette and rejection was not statistically significant in either parental gender, so was not plotted. The endorsement of Korean traditional etiquette was correlated with negative discipline among fathers (b = 0.169; p < .05) but not among mothers. The plots are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Simple slope analyses of significant interactions

Discussion

Family is, without a doubt, crucial to the development of children, while also representing culture and ethnicity. For youth who are a cultural and/or racial-ethnic minority, including Asian Americans, the importance of an enhanced and accurate understanding of the family cannot be understated. However, there is lack of empirical knowledge on Asian American parenting. Some, like “tiger mom,” portray Asian American parenting as extremely controlling and harsh (Chua, 2011). Others maintain that Asian American parenting is a unique combination of parental control and warmth that, although different from Western parenting, is not coercive, punitive, or harsh (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Kagitçibasi, 2007). This study contributes to this understudied area of research by empirically testing the associations between a set of recently developed Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures and several commonly used Western parenting measures to accurately describe Asian American family processes, specifically those of Korean Americans.

Overall, the results of the study present a nuanced and detailed picture of Korean American parenting as a blend of Western concepts of authoritative and authoritarian styles and show the coexistence of positive and—though quite limited—negative parenting. In short, certain aspects of ga-jung-kyo-yuk are positively associated with the authoritative or authoritarian style, or even with both of them simultaneously. In fact, the positive bivariate correlation between authoritative and authoritarian styles may provide additional empirical support that, among Korean immigrant parents, authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles are not clearly distinctive or negatively related, as it is the case in European American families (Deater-Deckard, et al., 2011). In addition, the study finds that the associations between Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk measures and Western parenting measures remain unchanged, regardless of whether demographic and parental acculturation variables are accounted for. They also are largely similar across mothers and fathers with only a couple of exceptions.

Associations of Korean ga-jung-kyo-yuk and Western Parenting

The endorsement of traditional core cultural values (indicated by traditional parental virtues and enculturation of familial/cultural values) was positively associated with several parenting constructs that are regarded as ideal and positive in Western parenting theory, such as authoritative parenting style, parental warmth and acceptance, monitoring, and parent-child communication. This finding is not surprising, given that core Korean values include an emphasis on parental role-modeling of good behaviors, including respect for parents and elders, trust between parent and child, the centrality of family, and family obligation. Although varying in degrees, these values are shared across cultures and likely promote parenting that establishes strong parent-child relationships by practicing firm rules and monitoring, parental warmth, acceptance, and communication.

It is also possible that Korean American parents may be establishing bicultural parenting in which they continue to endorse traditional cultural values while adopting certain idealized Western parenting practices and values. A traditional Korean parenting virtue is sternness, with few overt expressions of parental love (K. Kim, 2006). Accordingly, warmth is often expressed nonverbally and indirectly. In fact, in the survey used in this study, more than 90% of Korean immigrant parents reported employing indirect expressions of affection (e.g., cooking a child's favorite dishes, working hard, sacrificing, etc.). However, the item of “stern parenting” was dropped from the original Korean traditional parental virtue scale (Choi, et al., 2012), a sign that stern parenting may be no longer endorsed in this new cultural environment, which further supports the possibility of bicultural parenting. In a similar vein, the results show that the indicators of parental acculturation to mainstream culture (i.e., English competence and participation in mainstream culture) were positively associated with authoritative style, warmth, and communication (see Tables 3 and 4). Adherence to Korean culture, on the other hand, was associated positively with authoritarian style and negative discipline but also with warmth, providing additional evidence of possible bicultural processes among immigrant families. Nonetheless, the associations between Korean American and Western parenting measures were unchanged when parental acculturation variables were accounted for, which indicates that the associations are immune to parental acculturation. However, parenting itself may go through the process of acculturation, and bicultural explanation cannot be ruled out.

The degree to which parents would like to maintain Korean traditional etiquette was associated with both authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles as well as parental acceptance. This finding may suggest that, although teaching a certain set of culturally appropriate behaviors that represent core values of family hierarchy and respect for elders may demand a strict set of behavioral rules (thus authoritarian) as alluded to earlier, parents may emphasize traditional etiquette while also providing the rationale of the behaviors and in the context of parental acceptance. In addition, despite the positive relation with authoritarian parenting, the emphasis on traditional etiquette was not related to parental rejection or negative discipline, indicating that the endorsement of the traditional etiquette does not evoke harsh parenting.

Another set of notable findings is on the measures of parenting practices of ga-jung-kyo-yuk. Eighty-two percent of parents reported co-sleeping with their children, which is thought to be a way to build parent-child bonding. However, such sleeping arrangements did not have significant relationships with any of the parenting constructs, positive or negative. In addition, beginning separate sleeping when the child was older was positively related to negative discipline. From this data, it is not clear whether there is a threshold of co-sleeping in Korean culture, and that beginning separate sleeping later is an indication of a child's problems (i.e., separation anxiety) or an overendorsement of the traditional method that may result in parent-child conflict and subsequent use of negative discipline.

The use of Korean traditional discipline was associated with authoritarian style, rejection, and negative discipline. In contrast to the hypotheses, it did not significantly relate to authoritative style or positive parenting constructs. Even though they were once used widely in Korea, these disciplinary practices among Korean immigrant families are associated with parental rejection and negative discipline. Because there are social sanctions on corporal punishment and because these specific methods are associated with negative parenting, which may increase parent-child conflict, Korean immigrant families will need to gradually phase out these practices from the ideal sense of ga-jung-kyo-yuk, in which one of the main goals is to establish a close parent-child relationship.

Mothers and Fathers: Similarities and Differences

The associations between Korean and Western parenting show great similarity across mothers and fathers. Two notable differences include that only mothers who use traditional disciplinary practices are less likely to provide parental monitoring, and only fathers who endorse Korean traditional etiquette are more likely to use negative discipline. Among both mothers and fathers, traditional disciplinary practices indicate parental rejection and negative discipline, while mothers reported a higher rate of using physical discipline than fathers in the survey. The negative impact on parental monitoring among mothers may be another reason to discourage the use of traditional physical discipline among Korean immigrant families. The culture of the Korean immigrant community, especially among the parent generation, remain largely patriarchal and male-centered (Min, 2006). It is possible that fathers may practice forceful or negative parenting in emphasizing tradition, such as Korean traditional etiquette. Korean traditional etiquettes were positively related to authoritarian parenting among both mothers and fathers, and it may be that this is an area in which stricter parenting is practiced, especially by fathers.

Study Limitations and Future Research

The study has some limitations that bear mentioning. First, the associations were tested using participants' self-reports and self-assessments of their parenting behaviors. Although self-reports are shown to provide valid and reliable information, it is also possible that children view these behaviors differently. Youth perception of parenting and family process is often significantly different from that of parents (Choi, He, & Harachi, 2008). The next steps of the research should be cross-validations of parental and youth reports of parenting behaviors and values, and a determination of how different or similar perceptions by youth and parents influence youth developmental outcomes.

Except for the measures of traditional disciplinary practices and sleeping arrangement, the majority of current measures of ga-jung-kyo-yuk focus on parental values. Conversely, the guan and qin measures evaluate specific behaviors of parental control and warmth. Because the value measures assess cultural beliefs and ideals, it may not be surprising that the measures are positively correlated with authoritative parenting, parental warmth and acceptance. As discussed earlier, it may be universal for parents to desire close and accepting relationships with their children. However, it may be actual parenting practices that are culturally distinct. For example, the specifics of parental involvement in child's education, decision making, and family rules and regulations may vary more significantly across cultures. However, guan behavioral measures were significantly and positively correlated with the ga-jung-kyo-yuk value measures (Choi, et al., 2012), demonstrating a possibility that ga-jung-kyo-yuk behavioral measures may also overlap with ga-jung-kyo-yuk value measures,. Nonetheless, the next step of research should include further development of specific parenting behaviors that are part of ga-jung-kyo-yuk and empirical examination of the relationships with Western parenting behavior measures.

Cultural differences and similarities in family process are complex and require rigorous methods, including culturally appropriate and specific measures and empirical support of relationships that can debunk stereotypes and misperceptions. This study contributes to knowledge-building in this area. We have shown both the utility and the limitations of Western styles of authoritative/authoritarian parenting to explain Asian American parenting processes, specifically, the Korean American process called ga-jung-kyo-yuk. Research should expand to enhance our understanding on specific family processes across cultures, especially understudied groups, such as Asian Americans and their subgroups, to better understand universals and culture specifics of family process. Such knowledge is critical for informing intervention programs that target the culturally diverse United States, as well as global populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. K01 MH069910), a Seed Grant from the Center for Health Administration Studies, and a Junior Faculty Research Fund from the School of Social Service Administration and the Office of Vice President of Research and Argonne Laboratory at the University of Chicago (to the first author).

Footnotes

The term “Asian Americans” refers to both U.S.-born Americans of Asian descent and Asian immigrants who were born in Asian countries and migrated to the U.S. and may or may not have been naturalized.

In contemporary Asian societies, however, things are changing drastically as children are growing up in an increasingly globalized world. In one of the articles for this special issue, Way and her colleagues found that in the contemporary Chinese society, parents place great emphasis on independence, autonomy and extraversion in children as they try to socialize children and prepare them for a changing world.

The divergence of individualistic and collectivistic cultures might have emerged in response to the disparate needs of early societies: for example, agricultural Asian societies demanded more group-oriented values, while nomadic Western societies required more independent values (Greenfield, 1994).

“Enculturation” means learning the culture and assimilating its practices and values. The term is often used to indicate the degrees to which children of immigrants or cultural minorities maintain or learn their heritage and culture.

Although both parents and a child from each family were invited to complete the survey, participating members varied across families. For example, for the first survey, the number of families where both parents and one youth participated was 120. Eighty-five families had a mother and a child, 14 had a father and a child, 26 had both parents but no child, 41 had mothers only, and 4 had fathers only. The primary reasons of nonparticipation were unavailability, time conflict or refusal to participate, rather than because the family was a single-parent household.

References

- Baumrind D. The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance abuse. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11(1):56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: International Review. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Trickett EJ. The “language, identity, and behavior” (LIB) acculturation measure. University of Illinois; Chicago: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR. Parenting cognitions and practices in the acculturative processes. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships: Measurement and Development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Buri TR. Parental Authority Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57(1):110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65:1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting. Vol. 4. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Harachi TW, Gillmore MR, Catalano RF. Applicability of the social development model to urban ethnic minority youth: Examining the relationship between external constraints, family socialization and problem behaviors. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15(4):505–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, He M, Harachi TW. Intergenerational cultural dissonance, family conflict, parent-child bonding, and youth antisocial behaviors among Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9217-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS. Acculturation and enculturation: Core vs. peripheral changes in the family socialization among Korean Americans. Korean Journal of Studies of Koreans Abroad. 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim YS, Drankus D, Kim HJ. Preservation and Modification of Culture in Family Socialization: Development of Parenting Measures for Korean Immigrant Families. Asian American Journal of Psychology, available on-line. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0028772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua A. Battle hymn of the tiger mother. Penguin Press; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Science. 3rd ed. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; Mahwah: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Ross R, Marrinan S, Schattner S, Gullone E. The relationships between perceived family environment and psychological wellbeing: Mother, father and adolescent reports. Australian Psychologist. 1999;34(1):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Sorbring E. Cultural differences in the effects of physical punishment. In: Rutter M, editor. Ethnicity and causal mechanisms. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Malone PS, Alampay LP, Sorbring E, Bacchini D, et al. The association between parental warmth and control in thirteen cutural groups. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25(5):790–794. doi: 10.1037/a0025120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ. The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Development. 1987;58:1244–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Family obligation, college enrollment, and emerging adulthood in Asian and Latin American families. Child Development Perspectives. 2007;1(2):90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM, Cocking RR, editors. Cross-cultural roots of minority child development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM. Culture and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huntsinger CS, Jose PE, Rudden D, Luo Z, Krieg DB. Cultural differences in interactions around mathematics tasks in Chinese American and European American families. In: Park CC, Goodwin AL, Lee SJ, editors. Research on the education of Asian and Pacific Americans. Information Age Publishing; Greenwich, CT: 2001. pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitçibasi Ç . Family, self, and human development across cultures: Theory and applications, second edition. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. Korean American parental control: acceptance or rejection? Ethos. 2005;33(3):347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Cain KC, McCubbin MA. Maternal and paternal parenting, acculturation and young adolescent's psychological adjustment in Korean American families. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2006;19(3):112–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2006.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Hong S. First-generation Korean-American parents' perception of discipline. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2007;23(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. Hyo and parenting in Korea. In: Kenneth HR, Chung OB, editors. Parenting beliefs, behaviors, and parent-child relations: A cross-cultural perspective. Pschology Press; New York City: 2006. pp. 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kurasaki KS, Okazaki S, Sue S, editors. Asian American Mental Health: Assessment theories and methods. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Min PG. Korean Americans. In: Min PG, editor. Asian Americans: Contemporary trends and issues. Pine Forge Press; Thousand Oaks: 2006. pp. 230–259. [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, Kim BSK, Chiang J, Ju CM. Acculturation, enculturation, parental adherence to Asian cultural values, parenting styles, and family conflict among Asian American college students. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports. 1995;77:819–830. [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP. Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) University of Conneticut; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Chung OB, editors. Parenting beliefs, behaviors, and parent-child relations. Psychology Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham J. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(2):147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Darling N, Mounts NS, Dornbusch SM. Over-time changes in adjustment and competence among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent and neglectful families. Child Development. 1994;65:754–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinden PG. Parenting attitudes and children's understanding of mind: A comparison of Korean American and Anglo-American families. Cognitive Development. 2001;16:793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. Acculturation. In: Landis D, Bhagat R, editors. Handbook of Intercultural training. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 1996. pp. 124–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Chao RK. Intergenerational cultural dissonance in parent-adolescent relationships among Chinese and European Americans. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(2):493–508. doi: 10.1037/a0021063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]