Abstract

Children and parents’ daily lives are rarely highlighted in coverage of drug wars. Using 16 interviews with parents in the Mexican border city of Juárez in 2010, we examine how drug violence impacts families with a focus on intersections of gender and social class. Related to mobility (the first emergent theme), fathers had increased mobility as compared to mothers, which caused different stresses. Material hardships heightened mothers’ isolation within the home, and mothers more often had to enforce children’s mobility restrictions, which children resisted. Related to employment (the second emergent theme), fathers took on dangerous jobs to provide for the family while mothers had fewer options for informal employment due to violence. In sum, men and women faced different challenges, which were intensified due to class-based material disadvantages. Conformity with traditional gender expectations for behavior was common for men and women, illustrating the normalization of gender inequality within this context.

Keywords: Intersectionality; violence; Ciudad Juárez (Chihuahua, Mexico); gender; poverty; families

Introduction

In 2008, Ciudad Juárez (Chihuahua, Mexico) was devastated by the effects of a global economic recession and a wave of drug-related violence. By 2009, the city had lost over 80,000 formal sector jobs (Kolenc 2010) and had the dubious distinction of being known as the most murderous city in the world (Chung 2010). Following Menjívar (2011, p. 9) in her call to “open up the optic” through which we examine violence, we consider how average members of society, in this case parents of young children, experience the context of violence. In the media coverage about drug wars and drug violence, children, mothers’, and fathers’ daily lives are rarely highlighted. In the academic context, previous research on violence in Juárez has focused on social organizing against the killing of women (Ensalaco 2006; Morales and Bejarano 2009; Staudt 2008; Wright 2001), assessment of trauma and injuries (Diaz-Apodaca et al. 2012; Leiner et al. 2012), displacement of residents from the city (Morales et al. 2013; Velázquez Vargas 2012), and experiences of those intimately involved in the drug war zone, such as traffickers and law enforcement agents (Campbell 2009). Utilizing 16 in-depth interviews with Juárez parents, this study examines how social class and gender, two intersecting social axes, shape divergent experiences with violence in this city.

Review of the Literature

In what follows, we briefly introduce intersectionality as our orienting perspective before reviewing relevant literature on social class, gender, and violence. Our use of an intersectional lens furthers understanding of life in violent contexts by focusing attention on how social class and gender are intertwined in this particular U.S.-Mexico border context. It also orients our methodological decisions, to be discussed later. Intersectionality is a tool for explaining how the unique contribution of one socio-demographic factor, such as gender, might be difficult to isolate from another, such as class (Oleksy 2011; Schultz and Mullings 2005). The focus is on understanding what is created and experienced at the confluence of two or more axes of oppression. An intersectional approach directs our gaze to how the more structural elements of social location blend with more personal aspects of experience, thus emphasizing context (Kelly 2011). In sum, intersectionality is used here as a framework for understanding how intersectional identities contour life experiences in a particular social context (Kelly 2011).

Social Class and Violence

Social class is one of two important social axes under consideration in this paper. By social class, we mean a family’s location in a stratification system related specifically to material standards of living, including income and possessions (Wright 2010). First, reductions in families’ social class can be caused by violence. This can happen because of changes in household composition due to killings and injuries of formerly employed adults the destruction of assets (e.g., damages to homes) and livelihoods or displacement and migration (Brentlinger and Hernan 2007; Justino 2009). Violent environments may also negatively impact households’ social class through reduced access to local exchange, employment, and social networks. Furthermore, conflict-related changes to credit markets, political institutions, and national-level economic growth can also reduce families’ access to material resources (Justino 2009).

Second, those with lower social class tend to suffer disproportionately from armed conflict as compared to those with higher social class. In the 1980s and 1990s, during the Colombian conflict, low-income, urban populations experienced the highest incidence of robbery and muggings (the most common impacts), even though violent crime was thought to more often target affluent populations (Jimeno 2001). At that time, the poorest people were suffering the highest rates of all types of violence in Colombia: murder, personal injury, family violence, and common crimes (Jimeno 2001).

Third, everyday challenges associated with lower social class can be exacerbated in a violent context. Social support networks, which are an important source of social and economic resources for poor families, can be disrupted, leaving them isolated and without assistance (McIlwaine and Moser 2001; Moser and McIlwaine 2004). Staying healthy and accessing needed health services when ill can also become more difficult; as such, the health impacts of violence in Latin America have been severe for poor residents, and these include child stunting due to inadequate nutrition, increases in tuberculosis, and mental health challenges (Brentlinger and Hernan 2007).

Gender and Violence

Gender is the second axis of social difference in this analysis where we direct our focus to the gendered nature of practices and behaviors. We start from the assumption that it is the performance of gender norms that give rise to masculinity and femininity, rather than some essential, biological basis (Fregoso and Bejarano 2010). These dominant notions of being a man or woman have real consequence as they reproduce power differentials (Menjívar 2011). Gender norm expectations in the Mexican context stem from traditional notions of marianismo and machismo, although people challenge and contest these stereotypes in daily life (Gutmann 1996). Marianismo is rooted in a secularized veneration of the Virgin Mary and emphasizes sacrifice, suffering, and self-denial for women. Practically, it is reflected in the societal expectation that Latin American women’s primary duties rest within the family, that they sacrifice themselves for their families, and that they take care of others before themselves (as reviewed in Menjívar 2011). Machismo, on the other hand, orients expectations of masculinity. Traditionally, a strong definition of machismo includes controlling women, infidelity, hard drinking, and bullying behavior, but contemporary masculinity is more nuanced and varied than this stereotype. Nonetheless, societal expectations for macho men include providing for the family and leading household decision-making (Gutmann 1996).

Accompanying performance of these varied gender norms are differences in men and women’s experiences coping with conflict. In Colombia, conflict and subsequent displacement hit women harder than men. Because women’s lives revolved more around the private sphere of domesticity, the loss of the socially and physically familiar environment was particularly traumatic (Meertens and SeguraEscobar 1996). Men’s spheres were wider in terms of geographical and social mobility and participation in public life, helping them to better weather displacement. But, as families reconstructed their lives, the impacts were greater for men than women. Many men were unemployed and unable to find work, which ruptured their masculine identity and status. Women were able to find employment in the domestic sphere, as their experience around the home allowed them to access the labor market as domestic servants and laundry women (Meertens and SeguraEscobar 1996).

There are also gender inequalities in the likelihood of becoming a victim of violence. Overall, men are more likely than women to be killed during armed conflicts. The increasing numbers of female-headed households in conflict zones exemplifies men’s specific vulnerability (El Jack 2003). However, women too face risks of bodily harm during armed conflict. In Juárez specifically, women have been killed in significant numbers, e.g., during the widely publicized feminicides in the 1990s. Studying armed conflict in Guatemala and Colombia, researchers reported that while men and women experienced fear in public spaces, their experiences with fear were also gendered in private spaces as young women were concerned about being raped in the home by male relatives, while men did not share parallel fears (McIlwaine and Moser 2001).

A Methodological Approach to Intersectional Research

An intersectional approach requires methodological considerations (Hankivsky et al. 2010). First, the intersectional approach privileges considerations of the social context (Kelly 2011). Understanding people’s experiences with violence in Juárez would be limited without recognition of the sociospatial dynamics that give rise to contemporary Juárez. In our case, we feel that specifics about Juárez, such as its U.S.-Mexico border location, are important to making sense of our data; we are less interested in trying to uncover overly general place-less principles about gender, social class and violence. Second, it is important to begin an intersectional study by taking into account where the researchers themselves are located in the social hierarchy and with relation to the community of study (Hankivsky et al. 2010). This reflects the feminist turn in the social sciences and the awareness that all knowledge is positioned. Researchers have particular standpoints, rooted in their social positions, which must be acknowledged and reflected upon during the knowledge generation process (Smith 2005). Third, intersectionality analyses are most effective when conducted through community-based approaches because community engagement improves knowledge translation and the applicability of research findings to social problems (Hankivsky et al. 2010). These three guidelines have been followed and will be described in what follows.

Social Context: Ciudad Juárez

In Juárez, the rise in narco-violence in 2008 occurred - not coincidentally - with the onslaught of a global economic recession which hampered the abilities of people to make a living in the city. While extending back to the colonial era is beyond the scope of this paper, policies and practices dating back to the 1940s are quite relevant to the current context of violence in Juárez. When the US's Bracero Program (1942-1964) – which legalized the movement of Mexican workers into the US during WWII to help with labor shortages – ended, several hundred thousand Mexican workers were relocated to Mexican border cities. The Mexican government then created the Border Industrialization Program (BIP) in order to alleviate unemployment and overcrowding in border cities like Juárez (Frey 2003; Liverman and Vilas 2006). The BIP spawned the development of industrial zones housing mostly US-owned transnational corporations (maquiladoras), which are allowed to import needed equipment and raw materials tax-free (Frey 2003; Liverman and Vilas 2006). The 1980s and early 1990s saw the World Bank and International Monetary Fund further the liberalization of Mexico’s economy, which culminated in the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. Because it reduced tariff barriers to trade, the passage of the NAFTA enabled continued industrial growth along the Mexican side of the border, especially in Juárez (Liverman et al. 1999). However, the majority of maquiladora workers take home less than $6.00 a day, which is only a third of what a family of four requires to meet their basic needs. This has led many low-income migrants to reside in squatter settlements on the fringes of the city while elites and middle-class residents live in formally developed urban neighborhoods.

As a result of the economic transformations occurring in the Mexican economy during the 1980s and 1990s, people migrated from rural areas to the border region in search of work. This rural-to-urban migration is seen in the population statistics for Juárez: the population more than doubled between 1980 and 2005, rising from 567,365 to 1,313,338 people (Consejo Nacional de Población 2005). It has been argued that “the social and physical infrastructure of Juárez could not sustain such excessive urban growth, which created a ’city spinning out of control’” (Morales and Bejarano 2009, p. 429). Morales and Bejarano (2009) have also argued that neoliberal policies, such as the NAFTA, have exacerbated social inequality along the border, which in turn perpetuated violence. One extreme example of such violence was the feminicides that occurred in Juárez. Between 1993-2003, over 600 women were murdered, and others are still missing today (Morales and Bejarano 2009).

A consequence of rapid population growth in Juárez has been the insufficient provision of social services, such as day care and health care, for residents. Before the rise in violence (i.e., in 2004), the federal government reported that there were insufficient day care services in the State of Chihuahua (in which Juárez is the largest city); in this state, only 15% of children under 6 were in day care centers (Instituto Nacional de Estadística 2007). Specifically in Juárez (in 2003), there were 70 day care centers in the city, which served only 7,667 children; this left 50,000 Juárez children in need of day care without it (Herrera Varela 2006). Health care services are also inadequate as health needs have outpaced health infrastructure development (Cervera Gómez 2005). For example, Seguro Social (the federal insurance program for the formally employed) operated only two hospitals and eleven clinics in 2002 (Cervera Gómez 2005).

Social inequality has loomed large as an underlying factor in the current epoch of violence. In reflecting on the causes of the current drug war, Campbell (2011) argued that there have been five key contributing factors. First, the maquiladora model has failed to produce upward economic mobility and social development for the majority of the border population over the past decade. Second, the global economic crisis of the 21st century closed Juárez maquilas and exported low-wage jobs to China, which left laid-off border workers with nothing to fall back on as the U.S. militarized its southern border with fences, walls, and more Border Patrol agents (Campbell 2011). The extent of the 2008-2009 layoffs were extreme: the Association of Maquiladoras in Juárez reported that 33% of maquila jobs in Juárez (approximately 83,000) were lost between January 2008 and June 2009 (Kolenc 2010).

Third, the neoliberal model championed by the former Mexican President Carlos Salinas and continued by the PAN administrations between 2000 and 2012 reduced the social safety net and broke down the old patronage networks that kept drug traffickers in line. Bitter political battles allowed little or no cooperation between the federal government and state/local governments to address the violence (Campbell 2011). Fourth, President Felipe Calderón’s “drug war,” which began in 2006 and has been partially sponsored by the U.S. government, has failed to curb cartel activities and has in fact spurred violence. North Americans’ demand for drugs and our liberal gun laws have also fueled Mexican drug trafficking and related violence. Fifth, since the 1990s, a “counterculture of crime” has arisen in Mexico, in tandem with economic decline. Marginalized unemployed and semi-employed workers, especially the youth, have become readily employable for cartels, gangs, and kidnapping/extortion rings (Campbell 2011).

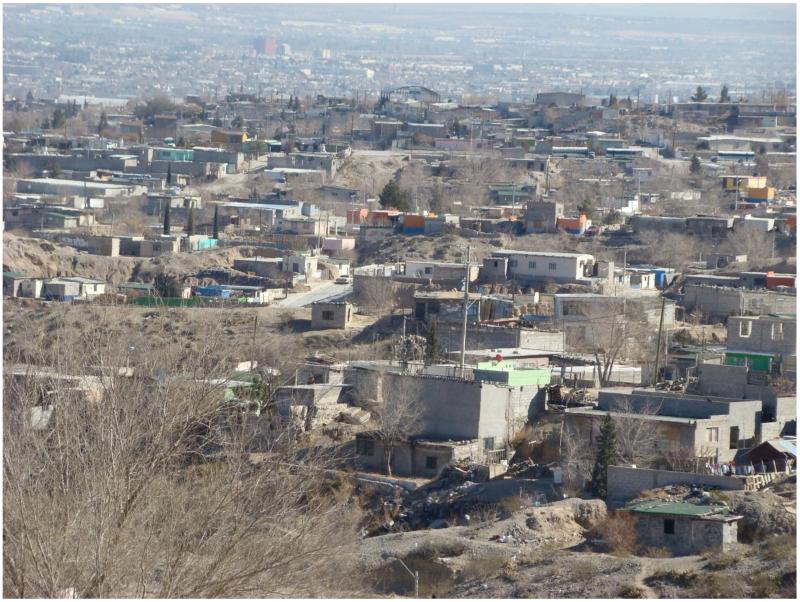

Contemporary Juárez (see Figure 1) is a difficult context in which to raise children. Between 2009 and 2010, the drug war left more than 10,000 children in Mexico orphaned and more than 40,000 relatives of victims affected by the violence (Paterson 2010). Some of the everyday problems for parents, apart from the murders, were business extortions, shootings, gruesomely violent imagery (e.g. public displays of dead human bodies and body parts), car theft, and dangerous traffic conditions as criminals evade police or crime scenes. Given this, parents felt pressure to keep their children inside the home (see Figure 2), and daily activities such as visiting the grocery store, or even the ride to school, were a challenge because of the occurrence of shoot-outs in the streets (Hernández 2011). During the peak of the violence, Juárez parents experienced high levels of distress and were constantly concerned about family safety. Over 95% of residents reported that they did not feel safe (Martínez-Cabrera 2011). Over 50% of crimes in Juárez are not reported to authorities as approximately 90% of residents have reported that they have no or little confidence in those responsible for security in the city. The majority of residents have had direct experiences with violence: in 2009 alone, according to the Encuesta de Percepción Ciudadana sobre Inseguridad en Ciudad Juárez (Survey of Citizens' Perceptions of Insecurity in Ciudad Juárez), 50% were victims of robbery, and 23% had been assaulted (Velázquez Vargas 2012); 71% had been in an area where someone was killed (Martínez-Cabrera 2011).

Figure 1.

Residential Area in Ciudad Juárez

Source: Alfredo Rodríguez, Graduate Student at El Colegio de la Frontera Norte

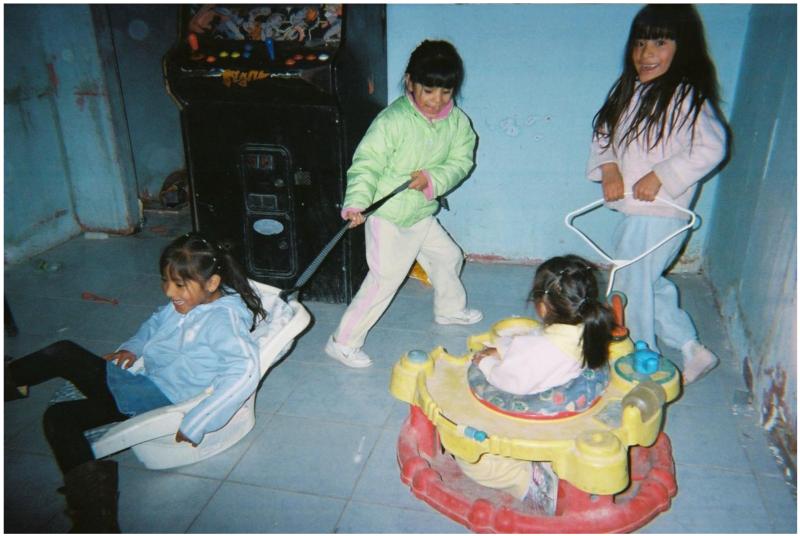

Figure 2.

Children playing inside the home

Source: Laura, participating mother (used with permission)

This insecurity has translated into a mass exodus of residents out of the city. Between 2007-2009, Juarez lost 230,000 residents, with 54% of them moving to the US (55,775 residents moved just across the border to El Paso, Texas) and the rest returning to their state of origin (which for the majority of residents is Durango, Coahuila, or Veracruz) (Velázquez Vargas 2012). Those who fled to the US were primarily upper- and middle-class residents (Morales et al. 2013). Many residents that remained in the city wished to leave: 42% of residents over 18 surveyed in 2009 were potential migrants, meaning that they desired to migrate to avoid becoming victims of crime, and of this pool, 62% were women who felt vulnerable to crime (Velázquez Vargas 2012). However, there are signs that the situation is Juárez is improving. Early in 2012, the Consejo Ciudadano para la Seguridad Pública y la Justicia Penal (Citizen Council for Public Safety and Justice) demoted Juárez from the most dangerous city in the world to the second most dangerous (after San Pedro Sula, Honduras), reflecting the drop in violence in recent months (Jensen 2012).

Data and Methods

This project was a collaboration between Gente a favor de gente or ‘People for the People’ (a Juárez community group co-led by the third author) and the first and second authors, who were based at the local university at the time of the project. As it is important for an intersectionality study, the authors’ positionality will be recognized before discussing the details of data collection. The three authors, all women ranging in age from mid-20s to late-50s, can be considered to fall on a continuum between “outsider” and “insider”. The first author moved to El Paso to accept a university position and is not of Mexican origin; however, she has been involved with Gente a favor de gente for several years, along with the second author. The second author was born in El Paso, raised in Juárez, and then graduated from high school and college in El Paso. While she is a regular border crosser and fully bilingual, she did not frequent the areas served by Gente a favor de gente before our involvement with them. The third author is a community-group leader with Gente a favor de gente who speaks only Spanish, and interacts with the interviewed families on a regular basis through a day care center that she operates. The composition of the team was advantageous to the research process as the different social positions of the three researchers may have contributed to a fuller understanding of the participants and their experiences (Hankivsky et al. 2010). Certainly, the team-based approach allowed the research to be completed in a sensitive way during a difficult time for the families interviewed. The third-author’s collaboration was a must as the university has prohibited faculty and students from crossing into Juárez to conduct research. The trust we had developed as a team while working together over the year before this project started (before crossing was prohibited) on another project (Hernández and Grineski 2010) was critical to its successful completion.

This project began when Gente a favor de gente enrolled 300 families in a child development intervention, which included a social survey, during 2009-2010, and the data were analyzed by the first two authors (Hernández 2011). Then, in a follow-up project that is the basis for this paper, we conducted in-depth interviews with 16 participating families to learn more about their experiences as parents (May/June 2010). The interviews occurred during the time period when the violence was at its highest point in recent years. The interviews were open-ended, and focused broadly on child-rearing practices, social networks, education, financial struggles, and impacts from the violence (contact the authors for a copy of the interview schedule).

To select the 16 people for interviews from the pool of 300, we used information provided in the survey. We began by identifying all parents who had more than one child based on the assumption that they would have more parenting experiences to recount during the interview. Within this group, we created two additional subgroups using caretaker’s employment; we randomly selected 8 parents employed in a maquiladora and 8 parents not employed in a maquiladora. We focused on maquiladora employment because maquiladoras are one of the main employers in the city and tend to provide their workers with resources such as access to the public housing program (i.e. INFONAVIT) and free public medical care (i.e. through Seguro Social). In the end, we did not compare these two groups because parents moved in and out of maquiladora employment during the study (due to lay-offs during the economic crash and then some re-hiring). It was not a stable axis from which to structure a comparison. Once the pools had been created, the third author (a community group leader and community health worker) contacted parents at random from those two subgroups to schedule interviews. If the selected parent was not interested in participating or unable to be located, another parent was selected at random to replace the uninterested parent until 8 interviews were conducted in each employment subgroup. All 16 participating parents were interviewed in their home by the third author (the interview was digitally recorded) and each received a $20 gift card to a Mexican grocery store. A subset of interviewed parents was also invited to take photos of their daily lives and some of the photos are featured in this paper (with permission).

IRB approval was granted for the project and all three authors are IRB certified. The interviews averaged 1 hour and 12 minutes (range: 49 min. to 2 hours and 3 min.) and were conducted with 14 mothers and 2 fathers. The interviews, conducted in Spanish by the third author, were transcribed (by the second author) and analyzed in Spanish using N*VIVO qualitative analysis software (QSR International 2007). The second author broadly coded “violence” as a pre-existing node within which the first author coded subthemes related to challenges living with the violence (which included extortion, robbery and murder) for the family. Using an inductive approach, we focused on gender and class because reviews of the transcripts revealed that these were important axes shaping life experiences for the participants. The following subthemes were identified (in the “challenges to living with the violence” node): reduced mobility, employment issues, impacts on children, extra responsibilities to care for relatives of the deceased, and distrust and fear. We focused on the subthemes of mobility and employment because the gender-class dimensions were quite evident in the transcripts and they were themes that contained significant amounts of interview data. They also cross-cut other themes, which allowed us to indirectly cover them address both private and public sphere challenges. Mobility and employment were further sub-coded into additional emergent sub-themes, which are discussed in the Results section.

Characteristics of participating parents are presented in Table 1. The median income of participating families was $205 (US) per month with a range of $103 to $376. As background information, sundries are similarly priced between the U.S. and Mexico, and it costs about $50 per week to feed a family in Juárez at a basic level (as cited in Morales and Bejarano 2009). Most of the interviewees (N=14) lived in two parent households and 10 of these families had a stay-at-home mother who reported no employment outside the home. With regards to education, the highest grade of education completed by the interviewee ranged from the 1st grade to 10th grade. Nearly half (n=7) of those interviewed had lived in Juárez their whole lives. In terms of direct experiences with violence and crime (based on a review of the interview data), participants had the following (which are underestimates, as we did not directly ask this in the interview): family member killed (n=3 participants); shootings in neighborhood or neighbor killed (9 incidents); police interrogation at work (n=1 participant); hid during a shooting (n=4 participants); and home robbed (n=2 participants).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants

| Pseudonym (Role) |

Interviewee’s Education |

Mother’s job | Father’s Job |

Monthly Income (US$)a |

Marital Status |

# of Children |

Length of Residence in Juarez |

Experienced Violence/Crime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maria (Mother) |

6th Grade | Stay at home mother |

Construction | $171 | Married | 3 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Josefina (Mother) |

8th Grade | Stay at home mother |

Construction | $240 | Married | 3 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Linda (Mother) |

Unknown | Stay at home mother |

Maquila | $205 | Married | 4 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Jose (Father) |

6th Grade | Maquila | Vends Food at Maqula |

$195 | Married | 2 | 6-10 yrs | Yes |

| Luz (Mother) |

8th Grade | Stay at home mother |

Maquila | $322 | Married | 3 | 1-5 yrs | No |

| Lucero (Mother) |

8th Grade | Maquila | N/A | $222 | Single | 2 | Lifetime | No |

| Monica (Mother) |

9th Grade | Stay at home mother |

Maquila | $171 | Married | 3 | Lifetime | No |

| Laura (Mother) |

6th Grade | Stay at home mother |

Maquila | $279 | Married | 2 | 6-10 yrs | No |

| Juan (Father) |

10th Grade |

Stay at home mother |

Vends Food |

$197 | Married | 2 | 6-10 yrs | Yes |

| Ana (Mother) |

9th Grade | Vends from home |

Grocery Store |

$171 | Married | 1 | 6-10 yrs | Yes |

| Lupe (Mother) |

1st Grade | Maquila | N/A | $260 | Single | 5 | >20yrs | No |

| Carla (Mother) |

6th Grade | Vends from home |

Car lot | $171 | Married | 3 | 11-20 yrs | Yes |

| Martha (Mother) |

6th Grade | Stay at home mother |

Mechanic | N/A | Married | 2 | <20yrs | Yes |

| Consuelo (Mother) |

6th Grade | Sells shoes | Maquila | $103 | Married | 3 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Rosa (Mother) |

10th Grade |

Stay at home mother |

Informal | $240 | Married | 2 | Lifetime | Yes |

| Teresa (Mother) |

3rd Grade | Stay at home mother |

Informal | $376 | Married | 2 | >20yrs | Yes |

Notes:

N/A = not available

We used the average exchange rate in 2010, which was 13.15 Mexican pesos per 1 U.S. dollar (Internal Revenue Service 2012).

Results

In what follows, we will discuss how gender and social class intersect within the spheres of mobility and employment to shape the experiences of mothers and fathers in a violent context. To preview our findings for the mobility theme, we found that fathers’ work outside the home put them at increased risk of experiencing violence in the public sphere as compared to mothers. Mothers were more restricted to the home, which had different impacts including stress and having to enforce children’s mobility restrictions. The challenges were more extreme for mothers without cars and cell phones. Under the employment theme, we found that men took dangerous jobs out of economic necessity in order to provide for the family. Women’s opportunities to supplement the family income through informal employment were reduced due to the violence and their lack of trust in day care services kept many women from working outside the home. Mothers working outside the home were concerned about having to work late and travel though the city in the dark and being away from their children for long hours. We elaborate each of these findings in the next sections.

Mobility Issues

First, fathers’ mobility put them at increased risk of experiencing violence in the streets as compared to mothers. The interviews demonstrated that men had increased mobility outside the home as compared to women due to their jobs, which related to their primary provider responsibilities in 14 of these families. Ana’s husband worked in a grocery store on a busy thoroughfare and he had experienced shootings on three separate occasions while commuting to and from work. She said:

Until now I haven’t experienced any of that, but my husband has, while being parked somewhere or even when he comes home from work scared and he says ‘it happened to me.’ I do not know if you remember when a pregnant woman was killed around Lopez Mateos [Avenue], that time he went in that direction and he was parked and when the shooting started, what he did is that he bent over and he moved aside to where they sell trailer parts; well, he says that he just bent over and he tried to move aside, to move out of the way, but it’s been three times already. Hasta ahorita a mí no me tocado nada de eso, pero a mi esposo si, a mi esposo ya sea que el este estacionado en un lado o incluso cuando llega a del trabajo asustado y me dice ‘me toco’. No sé si recuerda cuando mataron ahí por la López Mateos a una muchacha que estaba embarazada, esa vez él iba para allá y estaba estacionado y nada más empezaron los balazos y lo que hizo es que se agachó y se puso para un lado y donde venden cosas para las tráileres; bueno pues, dice que ya nada más se agachó y se trató de meter para un lado de quitarse, pero ya el ya van tres veces.

Ana clearly stated that she had not had these types of experiences because her employment (selling beauty products through a catalog company) was informal. She worked only through her social networks, and her clients visited her home.

A related issue was fathers (and mothers) not feeling comfortable with mothers going out alone with the children. For example, Laura did not take her daughters to the doctor’s office by herself given the danger. When asked if her interactions with health care providers had been impacted by the violence, she said:

Yes, because for example, to take my girls, I can’t go by myself for that reason. I have to wait for my husband to go… For example, the last time I had to ask my husband to come home from work. He had to leave his job because my daughter had a high temperature and that affects us, affects us economically, and the girl, because sometimes I have to wait a long time because I can’t go out by myself. Sí, porque por ejemplo pues, para llevar a mis niñas, pues yo no me puedo ir sola por lo mismo. O sea tengo que esperar a mi esposo para que vaya…. Pues por ejemplo, la última vez le tuve que hablar a mi esposo al trabajo a que se viniera. Se tuvo que salir del trabajo porque tenía a la niña con mucha temperatura y pos eso afecta, afecta económicamente y para la niña porque a veces espero demasiado por lo mismo porque no puedo salir sola

The need for the husband to accompany the wife on this caretaking task demonstrates gender-class intersections. Laura’s family lived paycheck-to-paycheck and so when her husband had to take time off work to accompany her to the clinic when their daughter was sick, it hurt them economically. In the past, this was a task that Laura would have done by herself, but it was not safe for her to do that at the time of the interview due to the violence. Laura’s quote also demonstrates how the violent context creates some fluidity while simultaneously maintaining traditional gender roles. In this instance, Laura’s husband was involved in what had traditionally been women’s work, albeit in a macho way that emphasizes protection.

Second, being unable to go out due to safety concerns and having primary caretaking responsibilities for children caused stress for mothers that seemed to be different than the stresses the father’s experienced. The women in this study (even those that worked outside the home) spent more time at home than did their husbands, caring for the children (Figure 3). While they were not at-risk of experiencing violence in the streets because of this, staying at home still had its attendant fears and associated emotion work. Martha, a stay-at-home mother, experienced fear until her husband and teenage son returned home:

Well, in regards to the children….that they go to school and come back fine. That is that they don’t fight outside of school. That is a worry. And that my husband gets to work fine and he comes back. Oh my god, until they’re back home, then you get calm. Pues en cuestión de los hijos verdad…que vallan a la escuela y vengan bien. Eso es de que no, que no se peleen fuera de las escuelas. Eh pos es una preocupación eso. Y que llegue mi esposo bien al trabajo y que regrese. Híjole no. Hasta que no están en casa ya están ya está uno tranquilo.

Martha’s husband was also worried about their teenage son going out.

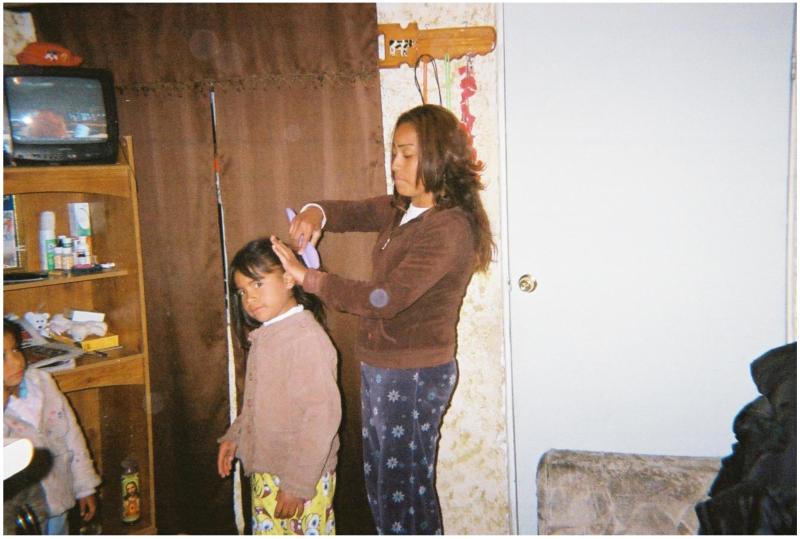

Figure 3.

Mother caring for her child in the home

Source: Guadalupe, participating mother (used with permission)

Carla, a former maquiladora employee who operated a small store out of her home at the time of the interview, explained the following about her fears:

…every time he [husband] leaves, I am afraid, and I feel that he isn’t going to come back. I tell you, when I was working [at the maquiladora], that was my fear, I said [to myself] 'what if my mother-in-law thinks of going to the store’, and I get scared. It is better that I go with her even if I have a lot of work to do, but how can I tell you, my children are my treasures, and I get really scared. The fact that even when you’re on the road, many people have seen shootings and it’s just a matter of walking away and giving thanks to God that nothing happened. …cada que se va yo tengo miedo y siento que ya no va a regresar… Como le digo ahora que estuve trabajando ese era mi miedo decía ‘que tal si a mi suegra se le ocurre irse a la tienda’ y pues me da miedo. Es mejor que me voy con ella y aunque esté bien saturada de trabajo pero, como le digo, para mí mis tesoros son mis hijos y sin nada, mucho miedo. El hecho de que a veces hasta cuándo va uno la carretera, cuanta gente no le ha tocado ver balacera y es nada más retirarse sólo y gracias a dios bien hasta que haya pasado nada.

Carla, like other mothers, worried about her husband who worked outside the home and about her children leaving home without her. With her husband away at work, Carla would have felt more comfortable accompanying her mother-in-law and children to the store than having her mother-in-law go alone with the children. She was fearful of something happening to her children when she was not there to protect them.

The reduction in mobility for mothers, as compared to fathers, due to the violence, is a reflection of gendered expectations for women’s behavior, e.g., their primary care-taking responsibilities. Some mothers worked operating small vending businesses out of their homes, which kept them closer to the children. However, they worried about family members, such as the husbands and older children, who had to leave the home to work and go to school. Apart from the stress, worry, and reduced mobility, women did find other aspects of their lives as stay-at-home mothers rewarding. Luz reported that she found the new things that her young daughter learned every day to be the most gratifying aspect of being a mother. Because she was not working outside the home at the time of the interview, Laura mentioned that she had more time to spend with her children, helping them with homework. She said that they chatted with each other and communicated more frequently now that she was home. When asked how it felt to be this sort of mother, she responded “Good, I feel very good” (Bien, me siento muy bien).

Third, because mothers were home with the children, they were the ones that needed to enforce the rules about keeping the children in the home, which the children sometimes resisted. Carla, whose husband worked in construction, prioritized keeping her children safe, but it was difficult:

Then as I tell you, the violence does harm you as a mother because you get really stressed out, and sometimes my kids come, before I would let them go play with the neighbor or here outside, but now you can’t even do that. And sometimes that they tease and tease saying “come on Mom, you only have us locked up, when you were little, Grandma says that she would let you go out.” It is very easy for me to tell him, fine, go out and play but… I have a window in the kitchen that looks out onto the street, and I hear the cars, and I feel really bad. I hear it and I think the worst. Entonces como le digo, le perjudica uno la violencia porque tanto como mama anda uno bien estresada, y a veces vienen mis niños y antes era dejarlos de ir a jugar con el vecino o aquí afuera y ahora no puede ni eso. Y ya estás a veces que están fastidie y fastidie, “nos tienes encerrados y cuando tú estabas chiquita mi abuelita me dice que te dejaba salir.” Se me hace muy fácil decirle ándale pues vete a jugar pero…yo tengo la ventana de la cocina hacia la calle y oigo los carros y no ya estoy y siento bien feo y lo oigo y pienso lo peor.

While Carla reported feeling bad about the restrictions she placed on her children, Rosa reported some marital tension related to her enforcement of these rules:

…[my husband] gets angry at me because the girl is just here standing in the doorway. It is a problem that he and I have because the girl stands in the door to go out, and she asks me and cries, she cries because she wants to go out but no. The other day it got worse because I went out, and they started shooting here close by and I immediately got her inside. The problem is that I can’t take her out to play. Se enoja conmigo porque la niña nada más está paradita aquí en la puerta. Es un problema el que tenemos yo y el porque la niña se para en la puerta porque quiere salirse para afuera y me dice y todo llora, llora porque quiere ir para afuera pero no. El otro día me salió peor porque salí y ahí estuve afuera y se dieron balazos aquí de volada y de volada la metí para dentro. O sea el problema es que no la puedo sacar a jugar.

Rosa’s husband wanted her to keep her daughter away from the door and inside, which Rosa struggled to do on a day-to-day basis.

Mothers tried to creatively keep their children entertained. When asked about her family’s evening routine, Consuelo illustrated what the family did, since they could not go out:

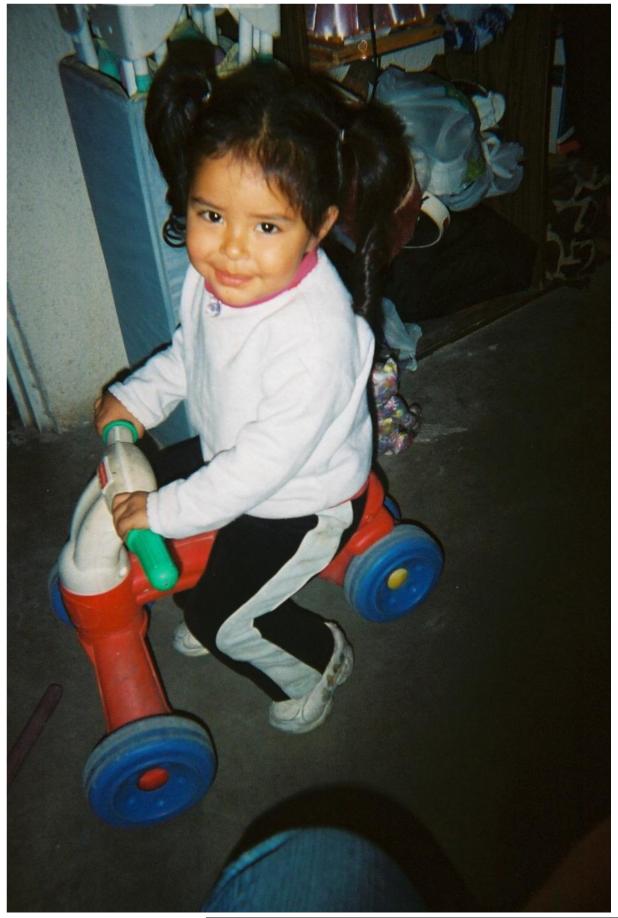

Well, in reality, we don’t do anything, sometimes we just turn on the radio and they start dancing. They really like to dance. We don’t do anything because after the evening we can’t go out. It is a very conflictive street, and we can’t do anything here, that is why we don’t let them go to the front. I don’t want the kids to be in the park playing, because at this moment with this insecurity, we don’t let them be outside. The only thing we do is play them music, they play and have their bicycles and roller skates here inside the house. They don’t do anything in the backyard. Pues, en realidad, no hacemos nada, a veces prendemos el radio y se ponen a bailar. Son muy bailadores. No hacemos nada porque ya aquí después de las tarde no podemos salir. Esto es una calle muy conflictiva y no se puede hacer nada aquí y de hecho por eso no los dejamos enfrente. No quiero que estén los niños ahí en el parque jugando, porque ahorita con esta seguridad, no los dejamos que estén afuera. Lo único que hacemos es ponerles música, andan jugando y tienen sus bicicletas y patines aquí adentro de la casa. No hacen nada en el patio.

Consuelo’s family was making the best of a difficult situation, but riding a bike in a small home (see Figure 4) was not the same as riding it outside. While the parents discussed this time spent inside as limiting and boring for the children, it may also be that all the time spent in close quarters in the homes caused stress amongst family members (although this was not directly mentioned by participants).

Figure 4.

Child riding her bike inside the home

Source: Rosa, participating mother (used with permission)

Fourth, material hardships, specifically not having a car or a cell phone, impacted mother’s mobility quite dramatically. Nearly all participants were afraid to leave their home. While this is likely the case for Juarenses of varying social classes, not having a car of one’s own increased difficulties. Jose indicated that because of the current rise in violence, his family was even more restricted in leaving the home:

You can’t go outside like you used to. I tell you, without a car, we did not go out that much, and now even less. I don’t know what is happening, but we would go out every eight days or so. Sometimes we would go to the public pools, or if there was a carnival to take them to, but not right now. Ya no puede salir una igual. Sí le digo sin carro, casi no salimos ni menos ahorita o sea no sé qué pasa pero este si salíamos a casi ocho días pero no. A veces, íbamos a las albercas o si había una feria para llevarlos, pero pues ahorita no.

In addition, while he was at work, he did not like his wife and children to leave the home. The family’s lack of transportation combined with the husband’s desires to protect his wife from harm kept her and the children in the home. These sorts of restrictions, not uncommon amongst the participants, reduced the mother’s and children’s ability to socialize outside the home. While no one reported going out as much as they used to, families with cars did seem to leave the home more often. As a point of comparison, Martha owned a truck, and she described running to the vehicle and locking the doors immediately and going to do what she needed done, like shopping for groceries for her family, very quickly. She was afraid, but was not as limited as Jose’s family, due to the fact that she owned a truck with automatic locks. While Martha hurried home, Jose’s family rarely went out at all (besides to work) because they did not have a car and were likely afraid to wait outside for the bus.

In addition to lacking transportation, lacking a cell phone was also problematic for six participants in this study. Not having a cell phone (a critical material hardship) increased the stress associated with living in this context of violence and further restricted stay-at-home mothers. For example, Juan did not have a cell phone, so when he left for work, he could not call home and check on his children and wife, which concerned him. As he left, he would tell his wife, “take care of the children” (‘cuida mucho los niños’). While he was gone, he asked that she not leave the home as there would be no way for them to be in contact. This impacted her parenting in that she had to entertain her children within the small space of her home.

Employment Issues

First, men’s obligations to provide financially for their families led them to take dangerous jobs out of economic necessity. Carla’s family exemplified this theme. Due to the recession, Carla’s husband lost his job at the maquila, where she felt he was relatively safe from the violence. Because of this, they could not pay for the car that they had bought on credit when they were more economically stable, so he went to return the car to the car lot. During this encounter, the car lot owner offered him work at the car lot to pay off what he owed and to make enough to eat. Because her husband had no certificate of formal job skills (e.g., car maintenance course), she said it was very hard for him to get a job as he was competing with people with certificates in the competitive job market. He accepted the position at the car lot, having no other choice. This was concerning to Carla, she said:

The fact that my husband is working [at a car lot] is very stressful, because we never imagined that he would be there, since they’re the places that have been attacked the most. Es un estrés bien grande ahorita como está trabajando mi esposo, porque nunca nos imaginamos que iba a estar ahí, porque son los lugares que más han estado atacando.

Carla felt that her husband was at great risk working at the car lot; and they were areas that had been getting attacked regularly (Campbell 2011). But because of their debt and lack of other options, he had no other choice but to take the position. It is worth noting that Carla did not take the job at the car lot, nor does that seem to be something the family considered. The car lot position was “gender-bound” (Menjívar 2011) in that it was a position that men, not women, held. In taking this job, Carla’s husband acted in line with expectations of machismo and served as the primary provider for the household, even though it was dangerous.

Second, women’s opportunities to supplement the family income through informal employment (like vending) were reduced due to the violence. While more media attention has been paid to the loss of maquiladora jobs and the slow rebound in the formal job sector (Kolenc 2010), many mothers in this study had also lost their abilities to informally employ themselves through vending. While they earned little doing this, they were able to augment the family’s income by doing so. While both men and women ran vending operations, women’s desires/responsibilities to stay near the home to protect their children meant that they were intimately affected by reduced abilities to vend, especially because few formal jobs were available. Teresa could not find formal employment, but she felt that she could not work informally through vending because of the violence. She explained:

Because there are no jobs anymore, not like before, when you had the pleasure of saying, “I don’t like this job, I’ll go to another one” because there were many jobs, but not anymore. Because of the violence, people are afraid and in panic. Like this food stand’s owner is the owner of the house, and he would tell us “if you want I can rent it to you so you can sell some taquitos” and now we don’t sell….There is a lot of violence, you can’t put up a food stand with candy because they come and assault you. Before, the people would say, “I don’t have a job but I am going to sell gorditas or whatever”, but that is not possible. There is an ethical crisis, and even on the news you see that the young person who sold hamburgers got killed, or the one that used to sell chicken. People are afraid, afraid to put up a business. What is going to happen is that even the big businesses are leaving, imagine! What are we going to do? If they are the ones that give us jobs and resources to eat. How are we going to survive here? Porque ya no hay trabajo, no es como antes que usted tenía el gusto de decir 'pues esté este trabajo no me gusta me voy al otro’ porque había mucho trabajo y ya no. Por la violencia, ya la gente tiene miedo y pánico. Como mi ese puestecito que está si es del dueño de esta casa y nos decía, 'si quieres, se los rento para que usted ponga ahí unos taquitos’ y ya no se vende… Es mucha la violencia ya no pueden poner un puestecito con dulces porque lo vienen y lo asaltan. Como antes, la gente decía 'no tengo trabajo pero voy a poder salir hasta vendiendo gorditas o lo que sea’ pero no se puede. Hay una crisis ética y hasta en las noticias se ve que mataron al joven que está vendiendo las hamburguesas o uno que vendía pollos. Y la gente tiene miedo, miedo de poner un changarrito. Lo que va a pasar es que hasta los grandes negocios se están yendo, imagínese. ¿Qué vamos a hacer?, si son los que nos dan fuente de trabajo y nos dan para comer. ¿De dónde vamos a salir adelante aquí?

In this study, mothers were more often affected by limited informal work options, which were attractive because they could be done while caring for small children, than were fathers. In Carla’s case, her father was afraid for her safety and prohibited her from setting up a vending operation in front of the house by denying her a loan to get her operation up and running. To work around this limitation, she sold candy out of her home only to people she knew (similar to Ana and her beauty products), but she demonstrated frustration at her father for not allowing her to open a little store. Instead of being prohibited by another as was Carla, Consuelo sanctioned herself and quit vending on her own. Her brother was killed outside of her house, where she used to sell flautas. She explained:

Yeah, because, for example, I used to sell food outside of my house and I used to have a flautas food stand, but I had to close it down because my brother was killed here outside of my house and it did affect us. Not anymore, not anymore. Pues, si, porque, por ejemplo, yo antes vendía comida afuera mi casa y tenía un puestecito afuera de flautas, pero tuve que quitarlo porque a mi hermano me lo mataron aquí afuera de mi casa y pues si afectó. Ya no, ya no.

In addition to this loss of income, she was supporting her brother’s wife and his children at the time of the interview, which added to their financial challenges. Nonetheless, she did not see public vending as an option any longer. However, in the three weeks prior to our interview with her, she had begun selling shoes, with her husband, to acquaintances and friends.

Third, parents’ lack of trust in day care services made the decision for the mother to work outside the home very difficult. Participants expressed serious concerns about the safety of children at day care centers. While two incomes would be advantageous, families felt more comfortable having the mother stay at home with the children. Rosa, whose goal was to become a nurse, although they could not yet afford her school fees, would like to be able to put her children in a day care center so that she could earn money and ease some of the financial challenges faced by her family. She said:

As the crisis is right now, [I would rather be] a working mother, but without abandoning my children. If there were more opportunities, for one who, I mean like a day care center, I would take them, but right now there was a day care center that burned over there. I was afraid of all of that, right, but it would be necessary for me to work, right, to help a little bit more here at home. Ahorita como está la crisis [preferiría ser] madre trabajadora, pero sin descuidar mis hijos. Si hubiera un poco más de oportunidad, para uno que, o sea que la guardería como eso si los llevaría, pero hay ahorita de la guardería que se quemó también allá. Si temía por todo eso verdad, pero sí haría falta que yo trabajara verdad para poder ayudar un poquito más aquí en la casa.

Rosa was aware of a widely reported incident in which a day care center was burned down due to the owners not paying extortion threats. Her understandable fears of day care centers did keep her family’s income lower, and it was she, as a mother, that stayed home with the children. None of the interviewed mothers felt that their children would be safe at a day care center and none were using a day care center at the time of the interviews.

Fourth and closely related to the lack of day care options, for mothers who were employed outside of the home, or interested in taking a job, was concern about having to work late and travel though the city in the dark or be away from their children for long hours. Their primary caretaking responsibilities shaped this concern. The recent history of horrific feminicides of maquila workers in the city may also have contributed to women’s fears of coming home alone in the dark. One of the two fathers interviewed, on the other hand, reported matter of factly that he worked overtime every week at his maquila. Lucero, who shared a home with 10 others (her parents, her brothers, their children, and her children), was concerned about losing her job at the maquiladora because they wanted her to work overtime and she was afraid to return by herself late, even on the bus (see Figure 5). Her sister cared for her daughters while she was at work, but Lucero needed to return to take over their care after her shift. As a single mother, she feared being laid off; she said:

Because of the danger, it’s like when sometimes in the maquila, they want me to stay overtime and work later, and I can’t. I have to take care of my girls, and sometimes I think that I’m going to be laid off because I don’t stay overtime. …It is because if I stay, I’m afraid of returning by myself, and if there is no bus, it’s worse. Porque es peligroso, cuando es que como en la maquila, quieren que me quede a veces tiempo extra de quedarme más tarde y no puedo. Tengo que llegar a cuidar mis niñas y a veces pienso que me van a correr porque no me quedo tiempo extra. … Es que si me quedo, me da miedo venirme yo solita y si no hay camión, peor.

When asked what time she would get off work if she stayed late, she replied “7 pm”. The third author then added, “and at that time, it is already dangerous,” and Lucero continued: “Yes, it is dangerous and they kill people” (Si, esta peligroso y matan gente). Both Luz and her husband used to work the night shift at the maquila. When they were both laid off, they left the city, but returned prior to our interview with them because they heard that the maquiladoras were hiring again. Her husband was re-hired; while Luz wanted to work again, she was afraid to do so. Because her husband worked nights, Luz was home with the children at night. It seemed like gendered childcare norms left women both worried about leaving their children to go to work and directly responsible for their care.

Figure 5.

Transportation used by maquiladora workers

Source: Timothy Collins, Associate Professor of Geography at University of Texas at El Paso

Discussion

Gender was an important axis of difference, which intersected with social class, to shape mothers’ and fathers’ experiences raising families in Juárez during this period. For mothers, adopting traditional gender roles was protective for their safety and personally meaningful, but it also caused stress and limited their family’s financial standing. Women’s traditional caretaking role reduced their mobility and their risk of being victimized in the streets as their husbands asked them to stay home. The women in two-parent families were able to stay home because their husbands were working, although many men had reduced hours due to the recession. The families, who were already poor, had falling incomes in the months leading up to the interview as economic conditions became increasingly severe. For the poorest of women, their mobility was further limited by material hardship (not having a car or cell phone) and preferences (both their own, their husbands, and their family members) that they stay at home.

Emotionally, the caretaking role likely provided women with a sense of purpose and a daily routine. But, adoption of the caretaking role also caused stress. For example, women were tasked with enforcing the family rules, which usually included keeping the children inside the home. It was also impossible for mothers to fully protect and care for all of their family members at all times. While mothers used creative strategies such as having children ride bikes in the living room, they worried when family members left the house and these worries were reinforced when horrible things happened, such as Josefina witnessing a shooting on a public bus with her children and the death of Consuelo’s brother in front of her house as she and her children looked on.

Economically, women’s adoption of traditional caretaking roles reduced their formal and informal employment options, as protecting the children on a day-to-day basis fell to them and they were increasingly uncomfortable working informally outside the home (e.g., vending home-cooked foods in the streets) while taking care of the children simultaneously. However, one way that women were creatively working within their restricted mobility to improve their family’s economic standing was to sell products to people they knew from inside their home while continuing to provide fulltime care to their children. While their ability to make money this way was limited, it was proactive. Apart from economic gains, informal work can provide low income women with opportunities to cultivate social ties that can lead to formal emotional and economic assistance when needed (Menjivar 2011, p. 170).

Overall, the paucity of social networks available to women in our study was notable. We had expected that women would report social networks, through which they could gain material resources and social support when needed to help them cope with the difficult context (Oyen 2002). Networks of reciprocity and trust amongst poor women have been commonly reported in the literature on urban Latin America and the urban poor in general (Lomnitz 1977; Oyen 2002). It may be these informal security systems were temporarily disbanded due to the extreme nature of the violence during the period in which we collected our data. During the interviews, all respondents reported that the violence caused them to limit their time with family and friends; 14 of the 16 said they did not really have local friends and only 5 had their parents living in Juárez. The majority was uncomfortable socializing with neighbors due to the violence, and had stopped going to church. While seemingly surprising, this sort of social isolation was also reported during the drug-related conflict in Colombia (Jimeno 2001; McIlwaine and Moser 2001; Moser and McIlwaine 2004).

Men’s enactment of the provider role put them at risk for being exposed to violence, but also shielded them from the day-to-day drama of being restricted in the home. Frightening events (e.g., witnessing a shooting) happened to them as they moved about the city, travelling to and from work. As their working hours were cut, which occurred for many of the fathers in these families, they became less able to provide for their families, which caused stress and hardship for them. In some cases, their provider responsibilities forced them to accept dangerous work (e.g., at the used car lot) in order to help the family economically, whereas the dangers caused women to stop working.

We found very few examples of men and women actively resisting the gendered expectations for their behavior. We did find some evidence of people redefining gender roles within the existing structure of gendered inequality in order to adapt to the violent situation (e.g., men entering traditional female spaces by accompanying women on household management tasks that involved leaving the home). In her study of violence in Guatemala, Menjívar (2011) demonstrated how gender inequality had been normalized to the point that men and women did not challenge it. An informal attitudinal survey conducted in Mexico City revealed that adults believed that mothers should care for the home (i.e., the children, husband and house, in that order) and that fathers should provide economically by working outside the home (Gutmann 1996). It is their work outside the home as breadwinners that gives men authority over women and children in the household (Menjívar 2011). Additional results from the Mexico City study demonstrated that men do care for children (although not usually babies) when they are “available”, but they are less often available than women and so women have less flexibility than men when it comes to absenting themselves from childcare (Gutmann 1996).

Certainly, women in our study had few opportunities to be “unavailable” for childcare as they had become increasingly isolated in the home to escape the violence. The violent context seemed to intersect with gendered expectations for behavior, thus women avoided public spaces and all that was associated with them, such as taking jobs in the formal sector and bringing children to the doctor, which reinforced their alignment with orthodox gender roles. Men in our study were often away from home working and looking for work. When men were home and available to help, several interviewees provided examples of men assisting their wives with childcare and cooking (see Figure 6 as an example). But the difficult economic times meant that men felt increased pressure to provide economically, which directed their attention away from the home. These wider social spheres inhabited by men may have helped them to emotionally weather the conflict, as Meertens and SeguraEscober (1996) depicted during the destructive phase of the violence in Colombia, although a greater presence in public life also put men at risk of being victimized. Furthermore, the global economic downturn accompanying the rise in violence in Juárez made it increasingly difficult for men to fulfill the expectation of economic provision, which likely had negative psychosocial and economic impacts on all family members.

Figure 6.

Father assisting a mother with preparing a meal for the family

Source: Monica, participating mother (used with permission)

Conclusion

Like Menjívar (2011, p. 3), we sought to expose the consequences of living in a society that has normalized violence and to depict what she calls the “long arm of violence.” In doing so, the intersectionality approach helped us to make explicit the fact that parents did not experience violence in the same way. Mothers and fathers living in Juárez during the worst years of the violence faced different challenges related to mobility and employment, which were intensified due to class-based material disadvantages, even amongst this generally poor group. Conformity to traditional gender expectations for behavior was common for the men and women interviewed, illustrating the normalization of gender inequality within this context. How gender inequalities played out for families that fled the city due to the violence is an open question that could be investigated in future studies. Interviews with Juárez refugees who now live in El Paso revealed that they face the stress of leaving relatives behind (who do not have crossing visas) and discrimination (Morales et al. 2013), but the gendered dimensions of these challenges have yet to be explored.

In contrast to other intersectionality studies of violence (see Chaudhry and Bertram 2009 for an exception) that address women’s experiences with domestic violence (Erez, Adelman and Gregory 2009; Kelly 2011; Meyer 2010; Nixon and Humphreys 2010), we instead applied an intersectional lens to a study of community violence and interviewed parents who were not “directly impacted” by violence in the traditional sense of experiencing personal bodily harm. In doing so, we included the voices of those not typically examined in studies of violent contexts. This aligns with Menjívar (2011, p. 9) in her call to “open up the optic” through which violence is examined.

We reached our conclusions by relying primarily on women’s voices, which included their reports of men’s experiences. While other intersectionality studies focus on one group’s experience to be able to fully understand them (e.g., Erez, Adelman and Gregory 2009), future intersectionality studies should seek to include participants with a range of statuses across their intersections of interest. In our case, the community-based nature of this project (the University-Gente a favor de gente collaboration), which enabled the research to be conducted during a sensitive time in Juárez, influenced the types of participants we were able to access; Gente’s initial participants in the child development intervention, from whom our interview pool stemmed, were primarily women.

However, our focus on women’s voices helped to illuminate how the violence in Juárez has affected the intimate spaces of the home. Our interview material illustrates not only the more obvious ways in which the violence has impacted women in the public sphere (e.g., they reduce their working hours), but also the more subtle ways that the violence seeps in to the private sphere (e.g., they have their children ride bikes in the living room). In doing so, we shed light on how the violence impacts the personal lives of women within their homes - even the stay-at-home mothers who rarely left the house - and explore its influence on everyday families. This is in contrast to other important studies of violence and women in Juárez, which focus instead on public organizing done by families of women killed in the feminicides of the 1990s (Ensalaco 2006; Morales and Bejarano 2009; Staudt 2008; Wright 2001). This focus contributes to a fuller understanding of the far-reaching and unequal impacts of violence as it invades the intimate space of the home and allowed us to examine how gender informs parenting in a violent context. By introducing these families through their words and photos, we have sought to illustrate the human toll that the violence has taken on regular people, struggling to make a living and raise a family, in a violent place.

Highlights.

Social class and gender intersected to shape parents’ experiences in Juárez

Fathers had increased mobility as compared to mothers

Lacking a car and cell phone heightened mothers isolation within the home

Options for informal employment were reduced, impacting mothers to a greater degree

Fathers’ role as provider forced them to take on dangerous jobs

Acknowledgements

We recognize UTEP students Lorena Mondragon and Paola Chavez-Payan for their assistance in reviewing our translations and UTEP Assistant Professor Ophra Leyser-Whalen for her review of the manuscript. We also acknowledge Carlos Vasquez, of Gente a favor de gente, for his support and work on this project. Finally, we gratefully recognize the participating families and we thank them for sharing their stories with us. This project was partially supported by Award Number P20 MD002287-05S1from the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Hispanic Health Disparities Research Center, the National Institute On Minority Health And Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health, or the Environmental Protection Agency.

Biography

SARA E. GRINESKI is an Associate Professor of Sociology in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology and the co-Director of the Environment Core of the Hispanic Health Disparities Research Center at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her research interests include social inequalities, environmental injustice, and health disparities in the U.S. Southwest and U.S.-Mexico border region.

ALMA A. HERNANDEZ is a Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Fellow and Doctoral Student in Sociology at the University of New Mexico. Her research interests include Hispanic health disparities, children’s well-being, health issues, and border crossing in US-Mexico Border populations.

VICKY RAMOS is the coordinator of Gente a favor de gente (People for the People), a Ciudad Juárez community group, and a community-health worker (promotora). She has coordinated Gente’s efforts since 2003 with the goal of bettering the lives of children by providing services to prevent them from becoming victims or participants in criminal activities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sara E Grineski, Environment Core of Hispanic Health Disparities Research Center, University of Texas at El Paso, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, 500 W University Av, El Paso, TX 79968, segrineski@utep.edu, 915-747-8471 (phone), 915 747 5505 (fax).

Alma A Hernández, Robert Wood Johnson Health Policy Fellow, University of New Mexico, Department of Sociology MSC05 3080, 1915 Roma NE Ste. 1103, Albuquerque, NM 87131, aahernan@unm.edu.

Vicky Ramos, Promotora (Community Health Worker) and Community Leader, Gente a favor de gente, A.C., Ciudad Juárez.

References

- Brentlinger PE, Hernan MA. Armed Conflict and Poverty in Central America The Convergence of Epidemiology and Human Rights Advocacy. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):673–77. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181570c24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Howard . Drug War Zone. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Howard No End in Sight: Violence in Ciudad Juarez. NACLA. 2011 May-Jun; [Google Scholar]

- Cervera Gómez, Luis Ernesto. Dirección General Regional Noroeste. El Colegio de la Frontera Norte Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres; Ciudad Juárez: 2005. Diagnóstico geo-socioeconómico de Ciudad Juárez y su sociedad; p. 355. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry LN, Bertram C. Narrating Trauma and Reconstruction in Post-conflict Karachi: Feminist Liberation Psychology and the Contours of Agency in the Margins. Feminism & Psychology. 2009;19(3):298–312. [Google Scholar]

- Chung A. The Toronto Star. Toronto: 2010. Ciudad Juárez, México: The world’s most dangerous place? [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Población . México D.F.: 2005. Delimitación de Zonas Metropolitanas. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Apodaca BA, De Cosio FG, Moye-Elizalde G, Fornelli-Laffon FF. Discharges for external injuries from a hospital in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica-Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2012;31(5):443–46. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892012000500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack El, Amani . Institute for Development Studies; London: 2003. Gender and Armed Conflict; p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Ensalaco M. Murder in Ciudad Juarez - A parable of women’s struggle for human rights. Violence against Women. 2006;12(5):417–40. doi: 10.1177/1077801206287963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erez E, Adelman M, Gregory C. Intersections of Immigration and Domestic Violence Voices of Battered Immigrant Women. Feminist Criminology. 2009;4(1):32–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fregoso Rosa-Linda, Cynthia Bejarano. A Cartography of Feminicide in the Américas. In: Rosa-Linda Fregoso, Cynthia Bejarano., editors. Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Américas. Duke University Press; Chapel Hill, NC: 2010. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Frey R. Scott. The Transfer of Core-Based Hazardous Production Processes to the Export Processing Zones of the Periphery: The Maquiladora Centers of Northern Mexico. Journal of World Systems Research. 2003;IX(2):317–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann Matthew C. The Meanings of Macho: Being a Man in Mexico City. University of California; Berkeley and Los Angeles: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O, Reid C, Cormier R, Varcoe C, Clark N, Benoit C, Brotman S. Exploring the promises of intersectionality for advancing women’s health research. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2010;9(5):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Alma A. Gente a favor de Gente—People Helping People: Assessing a Child Development Intervention in Colonias in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Children, Youth and Environment. 2011 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Alma A., Grineski Sara E. Exploring the Efficacy of an Environmental health Intervention in south Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Family and Community Health. 2010;33(4):1–11. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181f3b253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera Varela Bertha. Ciencia Sociales para el Diseño de Políticas Públicas. Universidad autonoma de Ciudad Juárez; Ciudad Juárez: 2006. Los niños y niñas de Ciudad Juárez: Riesgos sociales y derechos de infancia; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informatica . México, D.F.: 2007. Mujeres y hombres en México; p. 629. [Google Scholar]

- R Jensen, C. Justice in Mexico Project. Trans-Border Institute of the University of San Diego; San Diego, CA: 2012. Cuidad Juárez: No Longer Most Dangerous City in the World. [Google Scholar]

- Jimeno Myriam. Violence and social life in Colombia. Critique of Anthropology. 2001;21(3):221–46. [Google Scholar]

- Justino P. Poverty and Violent Conflict: A Micro-Level Perspective on the Causes and Duration of Warfare. Journal of Peace Research. 2009;46(3):315–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly Ursula A. Theories of Intimate Partner Violence: From Blaming the Victim to Acting Against Injustice Intersectionality as an Analytic Framework. Advances in Nursing Science. 2011;34(3):E29–E51. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182272388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolenc V. El Paso Times. El Paso, TX: 2010. Maquilas dodge the violence: Juárez plants hurt more by recession than drug violence. [Google Scholar]

- Leiner M, Puertas H, Caratachea R, Avila C, Atluru A, Briones D, de Vargas C. Children’s mental health and collective violence: a binational study on the United States-Mexico border. Revista Panamericana De Salud Publica-Pan American Journal of Public Health. 2012;31(5):411–16. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892012000500009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liverman Diana M., Robert G, Varady Octavio Chavez, Roberto Sanchez. Environmental Issues Along the United States-Mexico Border: Drivers of Change and Responses of Citizens and Institutions. Annual Review of Energy and Environment. 1999;24:607–43. [Google Scholar]

- Liverman Diana M., Silvina Vilas. Neoliberalism and the environment in Latin America. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2006;31(1):327–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lomnitz Larissa. Academic Press; San Francisco: 1977. Networks and Marginality: Life in a Mexican Shantytown. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cabrera Alejandro. El Paso Times. El Paso: 2011. Survey: More want US to help Juárez; p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- McIlwaine Cathy, Moser Caroline O. Violence and social capital in urban poor communities: Perspectives from Colombia and Guatemala. Journal of International Development. 2001;13(7):965–84. [Google Scholar]

- Meertens D, SeguraEscobar N. Uprooted lives: Gender, violence and displacement in Colombia. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 1996;17(2):165–78. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia. Enduring Violence: Ladina Women’s Lives in Guatemala. University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D. Evaluating the Severity of Hate-motivated Violence: Intersectional Differences among LGBT Hate Crime Victims. Sociology-the Journal of the British Sociological Association. 2010;44(5):980–95. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Maria Cristina, Cynthia Bejarano. Transnational sexual and gendered violence: an application of border sexual conquest at a Mexico—US border. Global Networks. 2009;9(3):420–39. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Maria Cristina, Oscar Morales, Angelica C. Menchaca, Adam Sebastian. The Mexican Drug War and the Consequent Population Exodus: Transnational Movement at the U.S.-Mexican Border. Societies. 2013;3:80–103. [Google Scholar]

- Moser C, McIlwaine CE. Encounters with violence in Latin America: Urban poor perceptions from Columbia and Guatemala. Taylor and Francis; New York, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon J, Humphreys C. Marshalling the Evidence: Using Intersectionality in the Domestic Violence Frame. Social Politics. 2010;17(2):137–58. [Google Scholar]

- Oleksy EH. Intesectionality at the cross-roads. Womens Studies International Forum. 2011;34(4):263–70. [Google Scholar]

- Oyen Else. Social capital formation as a poverty reducing strategy? Social capital and poverty reduction. In: UNESCO: Social and Human Sciences Sector of UNESCO, editor. Social Capital and Poverty Reduction: Which role for the civil society organizations and the state? 2002. pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson K. FNS: on-line, U.S.- México border news. Las Cruces, NM: 2010. Solidarity with a Besieged Sister City. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . NVivo7. Cambridge, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz Amy J., Leith Mullings., editors. Gender, Race, Class and Health: Intersectional Approaches. Hoboken, NJ Jossey-Bass: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Dorothy. Institutional Ethnography: A sociology for the people. AltaMira Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Staudt Kathleen. Violence and activism at the border: gender, fear, and everyday life in Ciudad Juárez. University of Texas Press; Austin, TX: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Vargas, María del Socorro. Desplazamientos forzados: migración e inseguridad en Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua. Estudios regionales en economía, población y desarrollo. 2012;7(Enero/Febrero):4–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wright Erik Olin. Logics of Class Analysis. In: Annette Lareau, Dalton Conley., editors. Social Class: How Does It Work? Russell Sage; New York: 2010. pp. 329–49. [Google Scholar]