Abstract

Vibrio anguillarum is a marine pathogen that causes vibriosis, a hemorrhagic septicemia in aquatic invertebrate as well as vertebrate animals. The siderophore anguibactin system is one of the most important virulence factors of this bacterium. Most of the anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes are located in the 65-kb pJM1 virulence plasmid although some of them are found in the chromosome of this fish pathogen. Over 30 years of research unveiled the role numerous chromosomal and pJM1 genes play in the synthesis of anguibactin and the transport of cognate ferric complexes into the bacterial cell. Furthermore, these studies showed that pJM1-carrying strains might be originated from pJM1-less strains producing the chromosome-mediated siderophore vanchrobactin. Additionally, we recently identified a chromosome-mediated anguibactin system in V. harveyi suggesting the possible evolutional origin of the V. anguillarum anguibactin system. In this review, we present our current understanding of the mechanisms and evolution hypothesis of the anguibactin system that might have occurred in these pathogenic vibrios.

Keywords: Iron transport, Siderophore, Evolution, Anguibactin, Vibrio anguillarum, Vibrio harveyi

Introduction

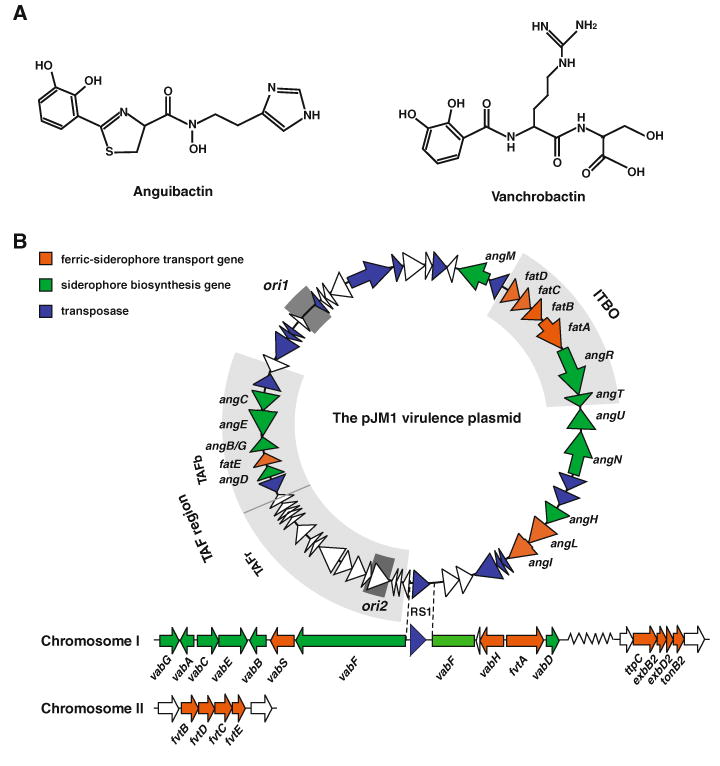

Anguibactin is a siderophore found in the pathogen Vibrio anguillarum that causes hemorrhagic septicemia, vibriosis, to aquatic vertebrates and invertebrates. This siderophore was originally identified as an essential virulence factor of the V. anguillarum strain 775(pJM1) (Crosa 1980). The structure of anguibactin, which was determined as a ω-N-hydroxy-ω-N-[[2′-(2″,3″-dihydroxyphenyl)thiazolin-4′-yl]carboxy] histamine molecule (Jalal et al. 1989), is unique since it contains catecholate and hydroxamate metal-chelating functional groups (Fig. 1a). Another unique property of the V. anguillarum anguibactin system is that the majority of genes involved in anguibactin biosynthesis and transport are encoded on the 65-kb pJM1 plasmid (Di Lorenzo et al. 2003). After the initial discovery of the correlation between the pJM1 plasmid and the production and utilization of anguibactin, many genes related to these processes have been characterized in Jorge Crosa’s laboratory as well as by international scientists to unveil this unique system. In this review, we describe our current knowledge of the pJM1 plasmid and mechanisms of anguibactin biosynthesis as well as ferri-anguibactin uptake. Furthermore, we discuss our hypothesis about the evolution of the anguibactin system present and expressed in V. anguillarum and V. harveyi.

Fig. 1.

a Structure of anguibactin and vanchrobactin. b Schematic map of the pJM1 virulence plasmid and chromosomal loci harboring genes involved in siderophore biosynthesis and transport. The location of two replication origins, ori1 and ori2, are highlighted as dark gray. Two well-characterized regions of pJM1, iron transport and biosynthesis operon (ITBO) as well as trans-acting factor (TAF) region composed of TAFb and TAFr, are highlighted as light gray. RS1, insertion sequence RS1 found in pJM1 and in the vabF gene on chromosome I

Plasmid-encoded anguibactin system in V. anguillarum

Anguibactin production and serotypes

Vibrio anguillarum has been divided into 23 distinct serotypes (O1–O23) by O serotyping (Grisez and Ollevier 1995; Pedersen et al. 1999; Sorensen and Larsen 1986). Of those, serotype O1, O2 and O3 strains have been recognized as etiological agents of fish vibriosis, while the rest of serotype strains are ubiquitously found in aquatic environments (Larsen et al. 1994; Silva-Rubio et al. 2008; Sorensen and Larsen 1986; Tiainen et al. 1997; Toranzo and Barja 1990). The pJM1-type plasmids have been only isolated from O1 serotype strains, and anguibactin is a sole siderophore for pJM1-carrying strains (Conchas et al. 1991; Lemos et al. 1988). It has been reported that pJM1-less serotype O1 strains and serotype O2 strains produce a chromosome-encoded siderophore, vanchrobactin (Balado et al. 2006, 2008; Naka et al. 2008; Soengas et al. 2006) (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, it appears that serotypes O3–O10 strains carry the genes involved in vanchrobactin biosynthesis and transport (Balado et al. 2009). Some serotype O2 strains carry some homologues of ferric-anguibactin uptake genes, however they are not active due to a transposon insertion (Balado et al. 2009). The correlation between V. anguillarum serotypes and the presence of the pJM1 plasmid is possibly due to the O1 side chain that is essential for the stability of the outer membrane ferric-anguibactin receptor FatA (Welch and Crosa 2005). However, FatA was stably detected in an O2 serotype strain when the pJM1 plasmid was artificially conjugated, indicating that FatA is also maintained in serotype O2 strains (Naka et al. 2008). Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms by which pJM1-type plasmids are only found in serotype O1 strains.

General features of the pJM1-type plasmids

The complete nucleotide sequences of the pJM1-type plasmids have been determined in two plasmids, the 65,009-bp pJM1 plasmid from V. anguillarum 775(pJM1) (Di Lorenzo et al. 2003) (Fig. 1b) and the 66,164-bp pEIB1 extrachromosomal element from V. anguillarum MVM425 (Wu et al. 2004). Although there are some differences between these two plasmids, all anguibactin biosynthesis and transport-related genes are highly homologous except that the pJM1 angN gene is annotated as two ORFs (orf27 and orf28) in pEIB1(Wu et al. 2004). There are two replication origins identified in the pJM1 plasmid. One of them, ori1, can replicate in both E. coli and vibrios, while the other, ori2, is only able to replicate in V. anguillarum (Naka et al. 2012). There are two well-characterized anguibactin-related loci in the pJM1 plasmid. One of them is the iron transport and biosynthesis operon (ITBO) composed of anguibactin biosynthesis and ferric-anguibactin transport genes, fatD, fatC, fatB, fatA, angR and angT (Di Lorenzo et al. 2003) (Fig. 1b). The expression of ITBO is upregulated under iron-limiting conditions in a Fur-dependent manner (Chai et al. 1998; Tolmasky et al. 1994). The N-terminus of AngR also activates the expression of this operon (Chen et al. 1996; Salinas et al. 1989; Wertheimer et al. 1999). Furthermore, two antisense RNAs (RNAα and RNAβ) encoded on the opposite strand of ITBO are involved in the regulation of this operon. RNAα, encoded on the opposite strand of the fatB gene, represses the expression of fatA and fatB under iron-rich conditions (Chen and Crosa 1996; Salinas et al. 1993; Waldbeser et al. 1993; Waldbeser et al. 1995). On the other hand, RNAβ, that spans the intergenic region between fatA and angR, terminates the majority of the ITBO transcript between fatA and angR (Salinas and Crosa 1995; Stork et al. 2007b). This termination event causes a higher expression level of fatDCBA mRNA than the entire fatDCBA-angRT mRNA. The other well-characterized locus in the pJM1 plasmid is the trans-acting factor (TAF) consisting of TAFb and TAFr regions (Welch et al. 2000). TAFb contains anguibactin biosynthesis genes such as angC, angE, angB/G and angD as well as a ferric-anguibactin transport gene fatE, whereas TAFr was shown to enhance the expression of ITBO, although the regulation mechanisms are still unknown (Salinas et al. 1989; Tolmasky et al. 1988; Welch et al. 2000).

Anguibactin biosynthesis

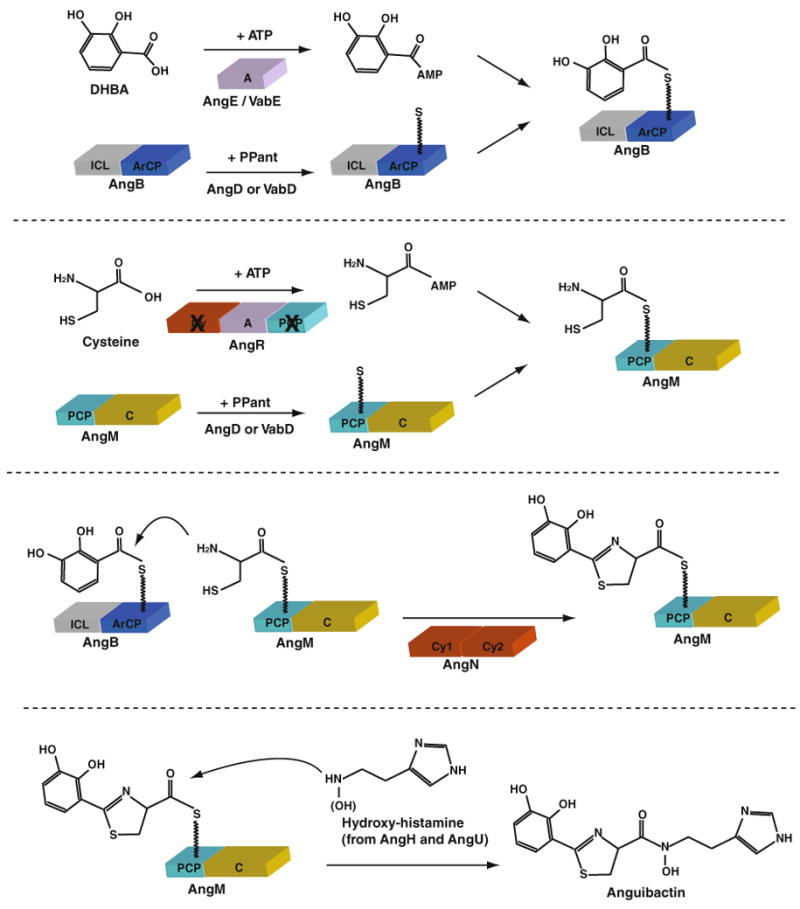

In V. anguillarum, many proteins are involved in anguibactin biosynthesis. The majority of them are encoded on the pJM1 plasmid (Ang) while some of them are coded by Vab genes located on the chromosome (Fig. 1b). 2,3-Dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHBA), a precursor of anguibactin, is synthesized by pJM1-encoded proteins, AngB/G (isochorismate lyase), AngC (putative isochorismate synthase) and AngE (2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-AMP ligase)] as well as by chromosome-encoded VabA (putative 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxybenzoate dehydrogenase). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that chromosome-encoded proteins VabB, VabC and VabE are functional homologues of pJM1-encoded AngB/G, AngC and AngE, respectively (Alice et al. 2005; Di Lorenzo et al. 2011; Naka et al. 2008; Welch et al. 2000) (Fig. 1b). AngB/G, AngE, AngM, AngN and AngR are non-ribosomal peptide synthases (NRPSs), and each protein provides domain(s) for anguibactin biosynthesis (Fig. 2). AngD and VabD are 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferases that are essential for anguibactin biosynthesis (AngD and VabD are functional homologues), and they are required to transfer a phosphopantetheinyl moiety to a serine residue located in the peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domain of AngM and the aryl carrier protein (ArCP) domain of AngB, making them become active forms (Liu et al. 2005; Naka et al. 2008). The adenylation domains (A) of AngE and likely of VabE activate DHBA into DHBA–AMP (Alice et al. 2005; Liu et al. 2004). The C-terminal region of AngB/G contains an ArCP domain required for tethering of DHBA–AMP, while the ArCP domain of VabB is not functional for angibactin biosynthesis suggesting the specificity of the VabB ArCP domain to vanchrobactin biosynthesis (Di Lorenzo et al. 2011; Welch et al. 2000). The A domain of AngR is essential for anguibactin biosynthesis, and it is likely involved in the activation of cysteine (Wertheimer et al. 1999). Although AngR additionally possesses PCP and cyclization (Cy) domains, these domains are not functional since an essential serine is replaced by alanine in the PCP domain while the essential first aspartic acid is replaced by asparagine in the Cy domain (Crosa and Walsh 2002). AngM contains the PCP domain that could tether the activated cysteine, and the condensation (C) domain that possibly catalyzes peptide bond formation between DHBA (from AngB) and cysteine (from AngM) (Di Lorenzo et al. 2004). AngN harbors two Cy domains (Cy1 and Cy2) and either Cy domains could condense and cyclize the DHBA and cysteine to form thiazoline (Di Lorenzo et al. 2008). AngH (histidine decarboxylase) and possibly AngU (putative monooxygenase) are involved in the modification of histidine into N-hydroxyhistamine (Tolmasky et al. 1995). In the final step of anguibactin biosynthesis, the C domain of AngM, one of the Cy domains of AngN, or a nucleophilic attack by hydroxylamine could be involved in the attachment of N-hydroxy histamine to the dihydroxyphenyl-thiazoline-thioester resulting from DHBA/cysteine condensation/cyclization. In this final step, the thioesterase (TE) domain of AngT could play a role in releasing anguibactin from AngM. However, the mutation in the angT gene did not completely abolish anguibactin production; it caused a 17-fold decrease in the production of this siderophore (Wertheimer et al. 1999). This observation suggests that AngT is not essential in this step or some chromosome-encoded protein harboring a TE domain might compensate this mutation.

Fig. 2.

Scheme of the proposed assembly line for the anguibactin biosynthesis by nonribosomal peptide synthetases in Vibrio anguillarum 775(pJM1). A adenylation domain, ArCP aryl carrier protein domain, C condensation domain, Cy cyclization domain, ICL isochorismate lyase, PCP peptidyl carrier protein domain, PPant phosphopantetheinyl moiety

Ferric-angubactin transport

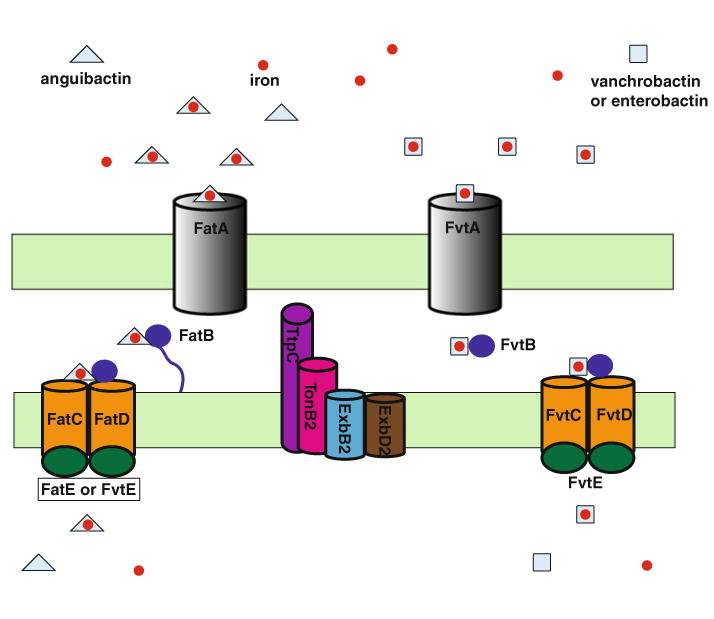

An active transport system is required to take up ferric-anguibactin from external environments into the V. anguillarum cytosol. To reach the cytosol, ferric-anguibactin needs to pass two biological barriers, the outer membrane and the cytoplasmic or inner membrane of this pathogen. At first, ferric-anguibactin is transported into the periplasmic space via the outer membrane ferric-anguibactin specific receptor FatA (Actis et al. 1985; Lopez and Crosa 2007; Lopez et al. 2007). During this process, as shown in many other Gram-negative bacteria, a TonB system is required to transmit energy generated by the cytoplasmic membrane proton motive force to the outer membrane receptor proteins (Krewulak and Vogel 2011; Noinaj et al. 2010; Postle and Larsen 2007). The TonB system proteins consist of TonB, ExbB and ExbD that anchor this protein complex in the inner membrane. In V. anguillarum two TonB systems, TonB1 and TonB2, have been identified. The TonB2 system is involved in the ferric-anguibactin transport and thus essential for the virulence of V. anguillarum (Stork et al. 2004). In addition to the typical TonB system proteins, TonB2, ExbB2 and ExbD2, a forth protein, named TtpC, was found to be essential for ferric-siderophore transport via the TonB2 system in V. anguillarum (Stork et al. 2007a). The TtpC protein is distributed in all Vibrio and aquatic bacteria, and it has been shown to be indispensable for TonB2 system-mediated ferric-siderophore transport in various Vibrio species (Kuehl and Crosa 2009, 2010; Kustusch et al. 2011, 2012; Stork et al. 2007a). In the periplasmic space, ferric-anguibactin is bound to the periplasmic-binding protein FatB anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane (Actis et al. 1995). The FatB protein seems to shuttle the ferric-anguibactin to the inner membrane permeases that consist of a heterodimer of FatC and FatD (Actis et al. 1995; Koster et al. 1991; Naka et al. 2010). FatB, FatC and FatD are essential for ferric-anguibactin uptake (Actis et al. 1995; Naka et al. 2010). Besides FatBCD which are considered part of an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter, another component of the ABC transporter encoding ATPases has been recently characterized. We identified two genes, fatE and fvtE, encoding ATPases involved in ferric-anguibactin transport (Naka et al. 2013a). The fatE gene is in the pJM1 plasmid, while fvtE is located on the small chromosome (chromosome 2) of V. anguillarum (Naka et al. 2011). Further analysis unveiled that fvtE is part of a chromosome cluster coding for ABC siderophore transport functions including FvtB, FvtC and FvtD, which that are homologues of FatB, FatC and FatD, respectively (Naka et al. 2011, 2013a). Moreover, genetic experiments demonstrated that fvtB, fvtC and fvtD are specifically responsible for ferric-vanchrobacin/enterobactin transport but not ferric-anguibactin. On the other hand, both FatE and FvtE are functional for ferric-anguibactin transport while only FvtE works for ferric-vanchrobactin/enterobactin transport (Naka et al. 2013a). Taken together, the pJM1-encoded ABC transporter FatDCB–FatE and the chromosome-encoded ABC transporter FvtBDCE are specialized for ferric-anguibactin and ferric-vanchrobactin/enter-obactin transport, respectively with the exception of FvtE, which is also functional for ferric-anguibactin transport. Our model of ferric-anguibactin transport in V. anguillarum is summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Ferric-anguibactin and ferric-exogeneous siderophore transport in Vibrio anguillarum 775(pJM1). FatA and FvtA are outer membrane receptors for ferri-anguibactin and ferric-vanchrobactin/enterobactin, respectively. The Fat ABC transporter consists of the periplasmic binding protein FatB anchored in the inner membrane, cytoplasmic membrane proteins FatC and FatD and the ATPase FatE are involved in ferric-anguibactin transport, while the Fvt ABC transporter consists of the periplasmic binding protein FvtB, inner membrane proteins FvtC and FvtD and the ATPase FvtE, functional for ferric-vanchrobactin/enterobactin transport. FvtE can also work for ferric-anguibactin transport. The TonB2 system consisting of TonB2, ExbB2, ExbD2 and TtpC is essential for both ferric-anguibactin and ferric-vanchrobactin/enterobactin transport

The pJM1-mediated anguibactin producer strain was originated from a chromosome-mediated vanchrobactin producer in V. anguillarum ancestor

As described above, some of anguibactin biosynthesis genes (vab) are located on the chromosome of V. anguillarum 775 (pJM1), a serotype O1 strain carrying the pJM1 plasmid (Alice et al. 2005; Naka et al. 2008). Further analysis revealed that this locus is comprised of the entire vanchrobactin biosynthesis and transport genes found in serotype O1 (pJM1-less) and O2 vanchrobactin producer strains (Naka et al. 2008). Nonetheless, V. anguillarum 775(pJM1) does not produce vanchrobactin because one of the vanchrobactin biosynthesis genes, vabF, is interrupted by a transposon that is identical to the transposon found in the pJM1 plasmid. The removal of the transposon from the vabF gene restored the production of vanchrobactin in addition to anguibactin. However, although biochemical assays could detect vanchrobactin production, biological assays did not detect vanchrobactin from the strain, possibly due to that the higher iron chelating capacity of anguibactin when compared to that of vanchrobactin (Naka et al. 2008). Thus, vanchrobactin is not functional as a siderophore in the strain that produces both anguibactin and vanchrobactin. Furthermore, the interruption of the vabF gene by the transposon is commonly found in the pJM1-type plasmid carrying serotype O1 strains isolated from different geographical regions. Based on these facts, we hypothesized that the serotype O1 pJM1-type plasmid-carrying strain was originated from the non-pJM1 strains that produce vanchrobactin. When the strains acquired the pJM1-type plasmid, the vabF was inactivated by the insertion of the transposon originated from the pJM1-type plasmid and thus the bacteria shut off vanchrobactin production (Naka et al. 2008). Possible remnants of the anguibactin system acquisition event were also found in serotype O2 strains. The fatA and fatD homologues were distributed in some of serotype O2a strains without carrying pJM1-type plasmids, although these strains did not harbor the anguibactin biosynthesis gene angR (Bay et al. 2007). Furthermore, the serotype O2b strain RV22 was showed to carry also the homologues of fatDCBA and some other genes in pJM1, even though these genes were not functional due to a transposon insertion in fatD (Balado et al. 2009). From these results, it is possible to speculate that not only serotype O1 but also O2 strains acquired the pJM1-like plasmids during evolution, however the entire plasmid only stayed in O1 serotype strains.

Chromosome-encoded anguibactin system in V. harveyi

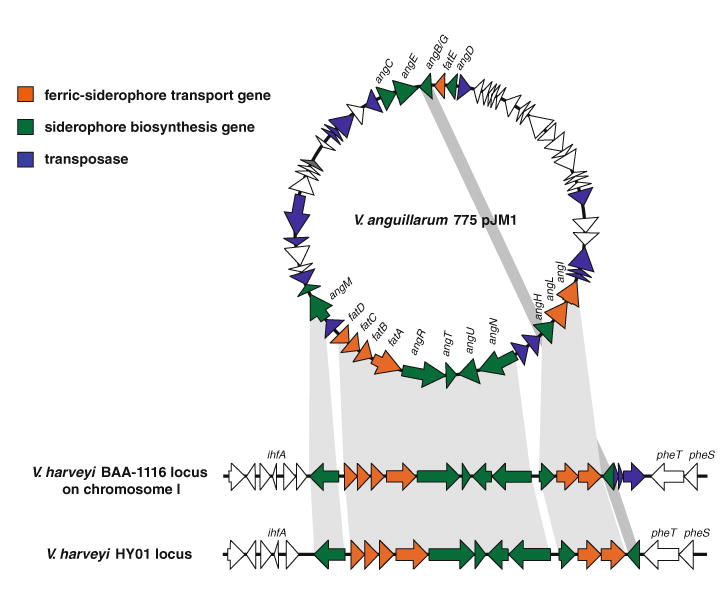

In addition to the plasmid-encoded anguibactin system described in V. anguillarum, we recently found a functional chromosome-encoded anguibactin system in V. harveyi. V. harveyi is a marine bacterium as well, and some of the strains are pathogens that mainly affect the shrimp aquaculture industry. Two sequenced strains of V. harveyi, BAA-1116 and HY01, carry a gene cluster containing homologues of the majority of anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes found in the pJM1 plasmid of V. anguillarum (Naka et al. 2013b) (Fig. 4). The gene organization of the V. harveyi anguibactin cluster is closely related to the V. anguillarum anguibactin cluster in the pJM1 plasmid. However, V. harveyi DHBA biosynthesis genes are found on a different chromosomal location and it appears that they are part of a gene cluster potentially involved in the biosynthesis and transport of an uncharacterized siderophore. We have shown that the V. haveyi angR gene is required for anguibactin biosynthesis and growth under iron-limiting conditions. Furthermore, the V. harveyi FatA ortholog is also an outer membrane protein indispensable for ferric-anguibactin transport. These two sequenced V. harveyi strains, BAA-1116 and HY01, have been proposed to be classified as V. campbellii by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) and multilocus sequence analyses (MLSA) (Lin et al. 2010). We also demonstrated that V. campbellii but not V. harveyi, as classified by CGH and MLSA, produces anguibactin by specific bioassay (Naka et al. 2013b). Furthermore, it was also reported that V. campbellii DS40M4 produces anguibactin, and the anguibactin cluster was found in its draft genome sequence (Dias et al. 2012; Sandy et al. 2010). Recently, further draft genome sequences of V. harveyi [CAIM 1792 (accession number AHHQ00000000)] and V. campbellii [PEL22A (Accession number AHYY00000000) and AND4 (accession number ABGR00000000)] in which the exact taxonomic position was determined based on genomic data, are available in public databases (Amaral et al. 2012; Espinoza-Valles et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2010). Analysis of these draft sequences show that V. campbellii PEL22A and AND4 strains harbor the anguibactin cluster while V. harveyi CAIM 1792 does not contain the anguibactin cluster supporting our speculation that V. campbellii instead of V. harveyi harbors the anguibactin system.

Fig. 4.

The anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes are conserved in V. anguillarum pJM1 and two V. harveyi strains, BAA-1116 and HY01. Grey shaded parts indicate that these genes are conserved between the three clusters. This Figure is modified from Fig. 1 of Naka et al. (2013b) MicrobiologyOpen

Conclusion

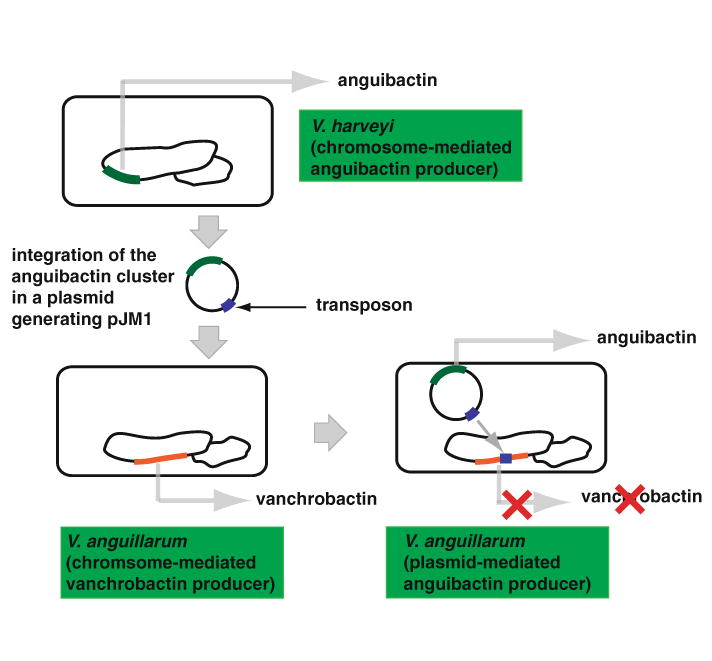

The pJM1-encoded anguibactin system of V. anguillarum serotype O1 strains is one of the best-characterized siderophore systems in Gram-negative bacteria. This unique system encoded on a plasmid and associated with virulence provides an important model to understand the mechanisms of siderophore biosynthesis and transport as well as its association with bacterial virulence. The majority of genes responsible for anguibactin biosynthesis and transport have been identified and genetically and/or biochemically characterized. We hypothesize that the pJM1-encoded anguibactin system probably originated from a V. harveyi strain harboring a chromosome-mediated anguibactin system that might have being acquired by a V. anguillarum pJM1-less strain, which produces the chromosome-mediated vanchrobactin, causing a disruption of a vanchrobactin gene to avoid the competition between these two siderophores (Fig. 5). Recent rapid advance in nucleotide sequencing technology has been providing us more access to microbial genome sequence data. Analyzing these genome data will enhance our understanding of distribution and evolution of the anguibactin system in bacteria that thrive in the aquatic environment.

Fig. 5.

Predicted model for evolution of the anguibactin system

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Lidia M. Crosa for reviewing the manuscript. The author’s work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants AI19018 and GM64600 to J. H. C. and AI070174 to L. A. A.

Contributor Information

Hiroaki Naka, Email: nakah@ohsu.edu, hiroakinaka1000@gmail.com, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA and Division of Environmental and Biomolecular Systems, Oregon Health & Science University, 20000 NW Walker Road, Beaverton, OR 97006, USA.

Moqing Liu, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA.

Luis A. Actis, Department of Microbiology, Miami University, Oxford, OH, USA

Jorge H. Crosa, Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA

References

- Actis LA, Potter SA, Crosa JH. Iron-regulated outer membrane protein OM2 of Vibrio anguillarum is encoded by virulence plasmid pJM1. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:736–742. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.736-742.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Actis LA, Tolmasky ME, Crosa LM, Crosa JH. Characterization and regulation of the expression of FatB, an iron transport protein encoded by the pJM1 virulence plasmid. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:197–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17010197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alice AF, Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Plasmid- and chromosome-encoded redundant and specific functions are involved in biosynthesis of the siderophore anguibactin in Vibrio anguillarum 775: a case of chance and necessity? J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2209–2214. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2209-2214.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral GR, Silva BS, Santos EO, Dias GM, Lopes RM, Edwards RA, Thompson CC, Thompson FL. Genome sequence of the bacterioplanktonic, mixotrophic Vibrio campbellii strain PEL22A, isolated in the Abrolhos Bank. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:2759–2760. doi: 10.1128/JB.00377-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balado M, Osorio CR, Lemos ML. A gene cluster involved in the biosynthesis of vanchrobactin, a chromosome-encoded siderophore produced by Vibrio anguillarum. Microbiology. 2006;152:3517–3528. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.29298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balado M, Osorio CR, Lemos ML. Biosynthetic and regulatory elements involved in the production of the siderophore vanchrobactin in Vibrio anguillarum. Microbiology. 2008;154:1400–1413. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/016618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balado M, Osorio CR, Lemos ML. FvtA is the receptor for the siderophore vanchrobactin in Vibrio anguillarum: utility as a route of entry for vanchrobactin analogues. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:2775–2783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02897-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay L, Larsen JL, Leisner JJ. Distribution of three genes involved in the pJM1 iron-sequestering system in various Vibrio anguillarum serogroups. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2007;30:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai S, Welch TJ, Crosa JH. Characterization of the interaction between Fur and the iron transport promoter of the virulence plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33841–33847. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Crosa JH. Antisense RNA, fur, iron, and the regulation of iron transport genes in Vibrio anguillarum. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18885–18891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Wertheimer AM, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. The AngR protein and the siderophore anguibactin positively regulate the expression of iron-transport genes in Vibrio anguillarum. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conchas RF, Lemos ML, Barja JL, Toranzo AE. Distribution of plasmid- and chromosome-mediated iron uptake systems in Vibrio anguillarum strains of different origins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2956–2962. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.2956-2962.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosa JH. A plasmid associated with virulence in the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum specifies an iron-sequestering system. Nature. 1980;284:566–568. doi: 10.1038/284566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosa JH, Walsh CT. Genetics and assembly line enzymology of siderophore biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:223–249. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.223-249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo M, Stork M, Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Farrell D, Welch TJ, Crosa LM, Wertheimer AM, Chen Q, Salinas P, Waldbeser L, Crosa JH. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pJM1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain 775. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:5822–5830. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.19.5822-5830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo M, Poppelaars S, Stork M, Nagasawa M, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. A nonribosomal peptide synthetase with a novel domain organization is essential for siderophore biosynthesis in Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7327–7336. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7327-7336.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo M, Stork M, Naka H, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. Tandem heterocyclization domains in a nonribosomal peptide synthetase essential for siderophore biosynthesis in Vibrio anguillarum. Biometals. 2008;21:635–648. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9149-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo M, Stork M, Crosa JH. Genetic and biochemical analyses of chromosome and plasmid gene homologues encoding ICL and ArCP domains in Vibrio anguillarum strain 775. Biometals. 2011;24:629–643. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9416-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias GM, Thompson CC, Fishman B, Naka H, Haygood MG, Crosa JH, Thompson FL. Genome sequence of the marine bacterium Vibrio campbellii DS40M4, isolated from open ocean water. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:904. doi: 10.1128/JB.06583-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Valles I, Soto-Rodriguez S, Edwards RA, Wang Z, Vora GJ, Gomez-Gil B. Draft genome sequence of the shrimp pathogen Vibrio harveyi CAIM 1792. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:2104. doi: 10.1128/JB.00079-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisez L, Ollevier F. Comparative serology of the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4367–4373. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4367-4373.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal MAF, Hossain MB, Van der Helm D, Sanders-Loehr J, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Structure of anguibactin, a unique plasmid-related bacterial siderophore from the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:292–296. [Google Scholar]

- Koster WL, Actis LA, Waldbeser LS, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. Molecular characterization of the iron transport system mediated by the pJM1 plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum 775. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:23829–23833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ. TonB or not TonB: is that the question? Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;89:87–97. doi: 10.1139/o10-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl CJ, Crosa JH. Molecular and genetic characterization of the TonB2-cluster TtpC protein in pathogenic vibrios. Biometals. 2009;22:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9194-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehl CJ, Crosa JH. The TonB energy transduction systems in Vibrio species. Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1403–1412. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustusch RJ, Kuehl CJ, Crosa JH. Power plays: iron transport and energy transduction in pathogenic vibrios. Biometals. 2011;24:559–566. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9437-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustusch RJ, Kuehl CJ, Crosa JH. The ttpC gene is contained in two of three TonB systems in the human pathogen Vibrio vulnificus, but only one is active in iron transport and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3250–3259. doi: 10.1128/JB.00155-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JL, Pedersen K, Dalsgaard I. Vibrio anguillarum serovars associated with vibriosis in fish. J Fish Dis. 1994;17:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos ML, Salinas P, Toranzo AE, Barja JL, Crosa JH. Chromosome-mediated iron uptake system in pathogenic strains of Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1920–1925. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1920-1925.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Wang Z, Malanoski AP, O’Grady EA, Wimpee CF, Vuddhakul V, Alves N, Jr, Thompson FL, Gomez-Gil B, Vora GJ. Comparative genomic analyses identify the Vibrio harveyi genome sequenced strains BAA-1116 and HY01 as Vibrio campbellii. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2010;2:81–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00100.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Ma Y, Wu H, Shao M, Liu H, Zhang Y. Cloning, identification and expression of an entE homologue angE from Vibrio anguillarum serotype O1. Arch Microbiol. 2004;181:287–293. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0652-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Ma Y, Zhou L, Zhang Y. Gene cloning, expression and functional characterization of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Vibrio anguillarum serotype O1. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:37–44. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Characterization of ferric-anguibactin transport in Vibrio anguillarum. Biometals. 2007;20:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10534-007-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez CS, Alice AF, Chakraborty R, Crosa JH. Identification of amino acid residues required for ferric-anguibactin transport in the outer-membrane receptor FatA of Vibrio anguillarum. Microbiology. 2007;153:570–584. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Reactivation of the vanchrobactin siderophore system of Vibrio anguillarum by removal of a chromosomal insertion sequence originated in plasmid pJM1 encoding the anguibactin siderophore system. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:265–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01450.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Lopez CS, Crosa JH. Role of the pJM1 plasmid-encoded transport proteins FatB, C and D in ferric anguibactin uptake in the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2010;2:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Dias GM, Thompson CC, Dubay C, Thompson FL, Crosa JH. Complete genome sequence of the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum harboring the pJM1 virulence plasmid and genomic comparison with other virulent strains of V. anguillarum and V. ordalii. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2889–2900. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05138-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Chen Q, Mitoma Y, Nakamura Y, McIntosh-Tolle D, Gammie AE, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. Two replication regions in the pJM1 virulence plasmid of the marine pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Plasmid. 2012;67:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Liu M, Crosa JH. Two ABC transporter systems participate in siderophore transport in the marine pathogen Vibrio anguillarum 775 (pJM1) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2013a;341(2):79–86. doi: 10.1111/1574-6968.12092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka H, Actis LA, Crosa JH. The anguibactin biosynthesis and transport genes are encoded in the chromosome of Vibrio harveyi: a possible evolutionary origin for the pJM1 plasmid-encoded system of Vibrio anguillarum? MicrobiologyOpen. 2013b;2:182–194. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noinaj N, Guillier M, Barnard TJ, Buchanan SK. TonB-dependent transporters: regulation, structure, and function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:43–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen K, Grisez L, van Houdt R, Tiainen T, Ollevier F, Larsen JL. Extended serotyping scheme for Vibrio anguillarum with the definition and characterization of seven provisional O-serogroups. Curr Microbiol. 1999;38:183–189. doi: 10.1007/pl00006784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postle K, Larsen RA. TonB-dependent energy transduction between outer and cytoplasmic membranes. Biometals. 2007;20:453–465. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas PC, Crosa JH. Regulation of angR, a gene with regulatory and biosynthetic functions in the pJM1 plasmid-mediated iron uptake system of Vibrio anguillarum. Gene. 1995;160:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00213-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas PC, Tolmasky ME, Crosa JH. Regulation of the iron uptake system in Vibrio anguillarum: evidence for a cooperative effect between two transcriptional activators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3529–3533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas PC, Waldbeser LS, Crosa JH. Regulation of the expression of bacterial iron transport genes: possible role of an antisense RNA as a repressor. Gene. 1993;123:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90535-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandy M, Han A, Blunt J, Munro M, Haygood M, Butler A. Vanchrobactin and anguibactin siderophores produced by Vibrio sp. DS40M4. J Nat Prod. 2010;73:1038–1043. doi: 10.1021/np900750g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Rubio A, Avendano-Herrera R, Jaureguiberry B, Toranzo AE, Magarinos B. First description of serotype O3 in Vibrio anguillarum strains isolated from salmonids in Chile. J Fish Dis. 2008;31:235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soengas RG, Anta C, Espada A, Paz V, Ares IR, Balado M, Rodríguez J, Lemos ML, Jiménez C. Structural characterization of vanchrobactin, a new catechol siderophore produced by the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum serotype O2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:7113–7116. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen UB, Larsen JL. Serotyping of Vibrio anguillarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:593–597. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.3.593-597.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork M, Di Lorenzo M, Mourino S, Osorio CR, Lemos ML, Crosa JH. Two tonB systems function in iron transport in Vibrio anguillarum, but only one is essential for virulence. Infect Immun. 2004;72:7326–7329. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7326-7329.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork M, Otto BR, Crosa JH. A novel protein, TtpC, is a required component of the TonB2 complex for specific iron transport in the pathogens Vibrio anguillarum and Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol. 2007a;189:1803–1815. doi: 10.1128/JB.00451-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork M, Di Lorenzo M, Welch TJ, Crosa JH. Transcription termination within the iron transport-biosynthesis operon of Vibrio anguillarum requires an antisense RNA. J Bacteriol. 2007b;189:3479–3488. doi: 10.1128/JB.00619-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiainen T, Pedersen K, Larsen JL. Vibrio anguillarum serogroup O3 and V. anguillarum-like serogroup O3 cross-reactive species—comparison and characterization. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;82:211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Genetic analysis of the iron uptake region of the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1: molecular cloning of genetic determinants encoding a novel trans activator of siderophore biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1913–1919. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1913-1919.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmasky ME, Wertheimer AM, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Characterization of the Vibrio anguillarum fur gene: role in regulation of expression of the FatA outer membrane protein and catechols. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:213–220. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.213-220.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Crosa JH. A histidine decarboxylase gene encoded by the Vibrio anguillarum plasmid pJM1 is essential for virulence: histamine is a precursor in the biosynthesis of anguibactin. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toranzo AE, Barja JL. A review of the taxonomy and seroepizootiology of Vibrio anguillarum, with special reference to aquaculture in the Northwest of Spain. Dis Aquat Org. 1990;9:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Waldbeser LS, Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Mechanisms for negative regulation by iron of the FatA outer membrane protein gene expression in Vibrio anguillarum 775. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10433–10439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldbeser LS, Chen Q, Crosa JH. Antisense RNA regulation of the fatB iron transport protein gene in Vibrio anguillarum. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:747–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17040747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch TJ, Crosa JH. Novel role of the lipopolysaccharide O1 side chain in ferric siderophore transport and virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. Infect Immun. 2005;73:5864–5872. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5864-5872.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch TJ, Chai S, Crosa JH. The overlapping angB and angG genes are encoded within the trans-acting factor region of the virulence plasmid in Vibrio anguillarum: essential role in siderophore biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6762–6773. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6762-6773.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertheimer AM, Verweij W, Chen Q, Crosa LM, Nagasawa M, Tolmasky ME, Actis LA, Crosa JH. Characterization of the angR gene of Vibrio anguillarum: essential role in virulence. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6496–6509. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6496-6509.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhang H. Complete sequence of virulence plasmid pEIB1 from the marine fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum strain MVM425 and location of its replication region. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97:1021–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]