Abstract

Signaling pathways have become a major source of targets for novel therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Survival benefits achieved with sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, are unprecedented and underscore the importance of improving our understanding of how signaling networks interact in transformed cells. Numerous signaling modules are de-regulated in HCC, including some related to growth factor signaling (e.g., IGF, EGF, PDGF, FGF, HGF), cell differentiation (WNT, Hedgehog, Notch), and angiogenesis (VEGF). Intracellular mediators such as RAS and AKT/MTOR may also play a role in HCC development and progression. Different molecular mechanisms have been shown to induce aberrant pathway activation. These include point mutations, chromosomal aberrations, and epigenetically driven down-regulation. The use of novel molecular technologies such as next-generation sequencing in HCC research has enabled the identification of novel pathways previously underexplored in the HCC field, such as chromatin remodeling and autophagy. Considering recent failures of molecular therapies in advanced clinical trials (e.g., sunitinib, brivanib), survey of these and other new pathways may provide alternative therapeutic targets.

Key Words: Cascade, Chromatin remodeling, HDAC, Hippo, Liver cancer

Introduction: Mainstream Pathway De-regulation in HCC

Hepatocarcinogenesis is a complex and multi-step process resulting from a combination of epigenetic and genetic alterations. In recent decades, much effort has been made to identify key molecules involved in the development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Yet, our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of this disease remains rudimentary. Several studies using high-throughput genomic technologies such as array-based gene expression profiling or parallel sequencing have facilitated the development of a molecular classification for HCC [1]. A meta-analysis including a total of 603 patients led to the identification of 3 robust molecular subclasses, characterized by de-regulation of specific signaling pathways [2]. Studies of mutations in key oncogenes and tumor suppressors in HCC have revealed that the most frequently mutated genes are TP53, and CTNNB1; this has been further confirmed by next-generation sequencing studies. However, the great variability in the occurrence of these mutations points to the possible impact of the underlying etiology on HCC molecular aberrations. Moreover, as recently highlighted in renal cancer [3], intra-tumoral molecular heterogeneity in solid tumors can further complicate the interpretation of molecular information generated from single biopsies.

Multiple signaling pathways that affect cell proliferation, angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis are de-regulated in HCC (table 1), and have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [4, 5]. Among these, the most frequently reported pathways involve growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factor (IGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). IGF signaling is essential for the regulation of growth and development, and has been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of several malignancies, including HCC. Alterations of this pathway include allelic losses of the IGFR2 receptor (80%) and overexpression of the IGF2 ligand (16–40%) [5]. In addition, selective blockade of IGF signaling had antitumoral effects in experimental models of HCC [6]. Various components of the HGF/MET pathway have been suggested to contribute to HCC progression [7]. Furthermore, a gene signature suggesting MET activation was found in 40% of HCC patients [8], identifying patients with poor prognosis. EGFR signaling has also been shown to be present, with overexpression at both mRNA and protein levels [9]. De-regulation of EGF in cirrhotic tissue seems to impact HCC development, as shown in a gene signature able to predict prognosis in surgically resected HCC patients [10]. Moreover, a specific single nucleotide polymorphism in the EGF gene, which increases ligand half-life, correlated with the risk of HCC development [11]. On the hand, over-expression of both VEGF and its receptors has clearly been shown in HCC, which is significant considering the importance of angiogenesis in cancer in general and in HCC in particular [12, 13]. Moreover, high serum levels of VEGF have been associated with aggressive cancer behavior and poor prognosis [14]. Finally, there has been increasing interest in anti-fibroblast growth factor (FGF) therapy in HCC, based on evidence suggesting the importance of this system both in HCC progression and in acquired resistance to anti-VEGF therapy [15]. Moreover, a very recent publication has demonstrated that FGF19, which is amplified and overexpressed along with the known oncogene CCDN1 [16], acts as an oncogenic driver in HCC [17]. Unfortunately, the initial experiences of clinical trials with the FGF inhibitor brivanib as first and second line therapies have not yielded improved survival; however, in these trials patients were not selected based on the basis of FGF activation.

Table 1.

Molecular alterations identified in multiple signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma

| Altered Molecular Pathway | Relevant Molecule | Alteration | Molecular targeted therapies (Experimentally or clinically tested in HCC) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known pathways in HCC pathogenesis: | |||||

| Differentiation and development: | Wnt/beta-catenin | ||||

| CTNNB1 | Activating mutation/Overexpression | – | de La costa et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998 | ||

| Wie et al. Hepatology 2002 | |||||

| Taniguchi et al. Oncogene 2002 | |||||

| Cui et al. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003 | |||||

| Elmileik et al. J Surg Oncol 2005 | |||||

| AXIN1 | Inactivating mutation/Lost of heterozygosity (LOH) | – | Sato et al. Nat Gen et 2000 | ||

| Laurent-Puig et al. Gastroenterol 2001 | |||||

| Taniguchi et al. Oncogene 2002 | |||||

| Park et al. Liver Int 2005 | |||||

| APC | Inactivating mutation | – | Guichard et al. Nat Genet 2012 | ||

| Notch | Gamma secretase, DAPT | ||||

| NOTCH1 | Overexpression | Giovanni et al. J Hepatol 2009 | |||

| NOTCH3 | Overexpression | ||||

| Hedgehog | |||||

| SHH | Activating overexpression | ||||

| SMO | Activating overexpression | GDC-0449/Vismodegib, cyclopomine | Patil et al. Cncer Biol Ther 2006 | ||

| HHIP | Down-regulated by LOH/hypermethylation | ||||

| Cell cycle regulation: | p53/cell cycle | ||||

| TP53 | Inactivating mutation/LOH | Gene-therapy Ad5CMV-p53 gene | Hsia et al. Oncol Rep 2000 | ||

| Xu et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001 | |||||

| Laurent-Puig et al. Gastroenterol 2001 | |||||

| Elmileik et al. J Surg Oncol 2005 | |||||

| CDKN2A [pl6] | Inactivating mutation/Hypermethylation | Flavopiridol | Matsuda et al. Gastroenterol 1999 | ||

| IRF2 | Inactivating mutation | – | Guichard et al. Nat Genet 2012 | ||

| Proliferation: | EGF | ||||

| EGF/EGFR | Up-regulated | Erlotinib, Gefitinib, Cetuximab, Lapatinib | Motoo et al. Liver 1991 | ||

| Heize et al. Anticancer Res 1999 | |||||

| Ito et al. Br J Cancer 2001 | |||||

| Vilanueva et al. Gastroenterol 2008 | |||||

| HGF/MET | |||||

| HGF | Up-regulated | SU5416/11274 | Efinova et al. Eur Surg Res 2004 | ||

| HGFR | Up-regulated | Cabozantinib (XL184), | Boix et al. Hepatol 1994 | ||

| (MET) | Foretinib | Ueki et al. Hepatol 1997 | |||

| IGF | |||||

| IGF-2 | Overexpression | IMC-A12/Cixutumumab | Li et al. Cancer Res 1997 | ||

| IGF-2R | Down-regulating mutation/LOH | De souza et al. Nat Genet 1995 | |||

| Oka et al. Hepatol 2002 | |||||

| PI3 K/AKT/mTOR | |||||

| PIK3CA | Activating mutation | BKM120 | Lee et al. Oncogene 2005 | ||

| PTEN | Down-regulating mutation/LOH | – | Yao et al. Oncogene 1999 | ||

| Yao et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001 | |||||

| MTORC1 | Up-regulated | Everolimus, Rapamycin | Vilanueva et al. Gastroenterol 2008 | ||

| RAS/MAPK | Sorafenib | ||||

| KRAS | Activating mutation | – | Weihrauch et al. Br J Cancer 2001 | ||

| Weihrauch et al. Int Arch Occup Environ 2001 | |||||

| RPS6KA3 | Inactivating mutation | – | Guichard et al. Nat Genet 2012 | ||

| Angiogenesis: | FGF | ||||

| FGF 19 | Up-regulated | – | Chiang et al. Cancer Res 2008 | ||

| Sawey et al. Cancer cell 2011 | |||||

| FGFR1/2 | Up-regulated/activating mutations | Brivanib | Mise et al. Hepatol 1996 | ||

| Huynh et al. Clin Cancer Res 2008 | |||||

| PDGF | |||||

| PDGFRA | Up-regulated | Sorafenib, Sunitinib, Imatinib | Lizuka et al. Oncogene 2003 | ||

| VEGF | |||||

| VEGF | Up-regulated | Bevacizumab | Mise et al. Hepatol 1996 | ||

| Misura et al. J Hepatol 1997 | |||||

| VEGFR2 | Up-regulating amplifications | Sorafenib, Brivanib, Sunitinib | Veikkola et al. Semin Cancer Biol 1999 | ||

| Yoshiji et al. Hepatol 2004 | |||||

| Emerging pathways: | |||||

| Chromatin remodeling: | Histone modification | HDAC | Up-regulated | LBH589/Panobinostat, vorinostat, romidepsin | Wu et al. Plos One 2010 |

| Lachenmeyer et al. J Hepatol 2012 | |||||

| Chromatin regulators | ARID1A/B | Inactivating mutation | – | Fujimoto et al. Nat Gen 2012 | |

| Guichard et al. Nat Gen 2012 | |||||

| ARID2 | Inactivating mutation | – | Fujimoto et al. Nat Gen 2012 | ||

| Guichard et al. Nat Gen 2012 | |||||

| Li et al. Nat Gen 2011 | |||||

| Inflammation: | Lymphotoxin | LTalpha | Up-regulated | LTbR-Ig (LT-a and -b highly expressed) | Haybaeck et al. Cancer Cell 2009 |

| TLR4 & Microbiota | TLR4 | Up-regulated | Rifaximin | Dapito et al. Cancer Cell 2012 | |

| Differentiation and development: | Hippo | MST1/2 | Down-regulated | – | Zhou et al. Cancer Cell 2009 |

| pYAP | Down-regulated | – | |||

| Miscellany: | Autophagy Oxidative & reticulum stress | – | Activated* | Chloroquine | Shimizu et al. Int J cancer 2012 |

| NFE2L2 | Activating mutation | – | Guichard et al. Nat Genet 2012 | ||

Indirect evidences.

Activation of the above signaling pathways leads to signal transduction involving cytoplasmic intermediates, mostly tyrosine kinases included in the RAS/MAPK and AKT/PI3 K/mTOR pathways. Unlike in other solid tumors (e.g., pancreatic tumors), RAS mutations are infrequent in HCC. Nevertheless, the RAS cascade is of special importance because it is one of the main targets of sorafenib, the only systematic therapy currently effective for advanced HCC [18]. Moreover, in resected HCCs, activated AKT correlates with increased recurrence risk of this cancer [19]. Robust evidence also indicates that the MTORC1 complex plays a role in HCC progression [9]. In fact, MTOR inhibitors such as everolimus are being tested in advanced clinical trials as first and second line therapy for HCC.

Besides growth factor-related pathways, some data indicate aberrant activation of pathways involved in cell differentiation and development, such as WNT signaling. A number of studies show the presence of mutations in CTNNB1, mostly in Western HCC cohorts [5]. Gene expression studies have also identified activation of this cascade in roughly 25% of tumors [1]. A recent study showed two different patterns of WNT activation in HCC and a potential WNT-blockade effect of sorafenib in experimental models [20]. Unfortunately, various strategies have failed to develop drugs effective for selective abrogation of WNT signaling. Other pathways related to cell differentiation have also been studied in HCC, such as Hedgehog (Hh) and Notch, but their role in HCC pathogenesis appears to be less prominent than that of WNT.

Emergence of Novel Therapeutic Targets in HCC

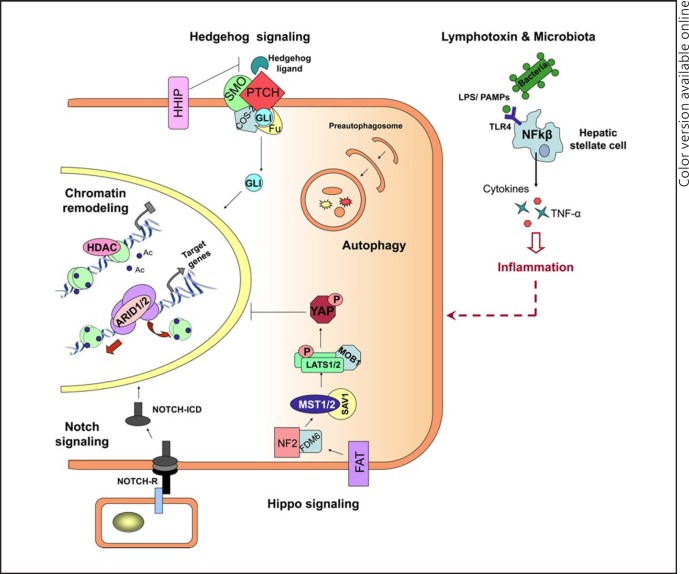

Based on data from randomized trials, HCC seems to be highly resistant to conventional chemotherapy [21]. However, the positive results achieved with sorafenib [22] demonstrate that molecular therapies could play a prominent role in systemic therapy for HCC. In fact, a number of novel targeted therapies are currently under evaluation in different clinical trials [18]. Considering the recent failures of some of these (e.g., sunitinib and brivanib), the identification of novel oncogenic addition loops in HCC has become a research priority. In other tumors, selective blockade of these events resulted in significant increases in patient survival (e.g., vemurafenib in BRAF-mutated melanoma or crizotinib in lung cancer with ALK rearrangements). In this review, we summarize recent findings of emerging altered signaling pathways involved in HCC and their potential as candidate targets for future personalized molecular therapies (fig. 1). In addition, we provide an update on some of the previously less-characterized pathways involved in cell differentiation, such as Notch and Hh.

Fig. 1.

Emerging signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Chromatin remodelling: Deacetylation (Ac) of histones within the nucleosomes by HDACs results in DNA condensation, restricting transcriptional activation. On the other hand, chromatin remodelling complexes, including ARID1/2, lead to transcriptional activation by facilitating access for the transcription machinery through nucleosome restructuring. Notch signaling: Binding of protein ligands to the extracellular domain of NOTCH receptors (NOTCH-R) induces photolytic cleavage of the receptor, releasing its intracellular domain (NOTCH-ICD), which then enters the nucleus and modifies expression of its target genes (e.g., HES, HEY, and SOX9). Hedgehog (Hh) signaling: In the presence of Hh ligands, PTCH releases its inhibitory effect on SMO, which is in a complex with COS-2 and FU, allowing the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor GLI. Hippo signaling: Upon stimulation, the upstream regulators of hippo pathway (e.g., FAT, NF2, and FDM6) activate the kinase complexes MST1/2-SVA1 and Lats1/2-Mob1, resulting in phosphorylation of the transcription factor YAP and preventing its nuclear translocation. Lymphotoxins and microbiota: The recognition of microbial ligands (LPS/PAMPs) by TLKRs (e.g., TLK4) on the hepatic stellate cells leads to activation of NF-kβ signaling and the consequent production of proinflammatory molecules, including cytokines and TNF-α.

Epigenetic Regulation and Chromatin Remodelling

Chromatin remodeling is a core epigenetic mechanism implicated in the control of gene expression; it provides dynamic access of condensed genomic DNA to the transcription machinery proteins. Hence, it plays an essential role in a variety of cell processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and DNA repair. The principal mechanisms involved in this process are enzymatic covalent histone modifications (e.g., methylation, phosphorylation, and acetylation) and nucleosomal restructuring by ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling complexes. In recent years, there has been growing evidence for a tumor suppressor role for these complexes, due to identification of frequent inactivating mutations of these components in different malignancies [23].

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are responsible for the transcriptional control of many genes involved in diverse cellular processes through chromatin remodeling, by histone acetylation or by functioning as transcriptional co-activators. There are 18 HDACs identified in mammals, which have been classified into four classes (Class I-IV) based on their DNA sequence similarity and function [24]. Currently, there is a strong body of evidence suggesting an important role for the HDAC machinery in cancer progression. Aberrant expression of several HDAC members (HDAC1–11) has frequently been shown to correlate with aggressive behavior of tumors and poor prognosis [25]. For this reason, HDAC inhibitors are increasingly being considered as one of the most promising anti-cancer drugs [26]. In fact, recently, two HDAC inhibitors (vorinostat and romidepsin) have received FDA approval for use in the treatment of cutaneous T cell lymphoma [27]. HDAC inhibitors exert their antitumor activity partly by means of histone hyperactelytion, resulting in reduced DNA-histone affinity, and thus facilitating access to transcription factors [28]. A recent study reported aberrant de-regulation of 11 HDACs in a cohort of surgically resected HCC [29]. A subset of HDACs (HDAC1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 11) was significantly up-regulated in HCC in comparison to normal liver tissue, and cirrhotic and dysplastic nodules. Furthermore, DNA copy number alteration analysis demonstrated significant DNA gains in HDAC3 and HDAC5, which correlated with their mRNA up-regulation. These findings partly correlate with those of a previous study in which HDAC expression levels were assessed through immunohistochemistry in a cohort of 43 HBV-related HCC cases [30]. A subset of HCCs presented increased expression of HDAC1 (51.2%), HDAC2 (48.8%), and HDAC3 (32.6%). Moreover, HDAC3 was determined to be an independent prognostic prediction factor for tumor recurrence following liver transplantation in HBV-related HCC.

Concomitantly, several studies have evaluated the efficacy of HDAC inhibitors, either alone or in combination with other agents, in preclinical HCC models. In particular, Lachenmayer et al. demonstrated that combination therapy with the pan-HDAC inhibitor (panobinostat) and sorafenib strongly potentiated treatment efficacy by significantly decreasing tumor volume and vessel density, and improving survival in HCC xenografts. This a proof-of-concept study that support the evaluation of these compounds in early clinical developmental phases in humans [29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36].

Recently, several studies in HCC have identified recurrent mutations in multiple chromatin regulators, including prominent members of the AT-rich interaction domain (ARID)-containing protein family. Gene-set enrichment (GSE) and functional analysis of whole genome sequencing data from 27 viral-associated HCCs identified recurrent mutations in a group of chromatin regulators (ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, MLL, and MLL3) in approximately 50% of the tumors [37]. This was further validated in an independent cohort of 120 HCCs, showing a mutation rate of 10, 6.7, and 5.8% for ARID1A, ARID1B, and ARID2, respectively. Interestingly, the frequency of inactivating mutations (non-synonymous mutations and indels) was significantly enriched in the chromatin regulator genes in comparison to other gene groups. Given that these mutations were marginally associated with liver fibrosis and hepatic vein invasion, it may be plausible that mutations in chromatin regulators contribute to aggressive behavior of HCC. Guichard et al. also identified chromatin regulators as the third most frequently mutated genes through whole-exome sequencing of 24 HCCs [38]. Interestingly, they reported that ARID1A mutations were more frequently associated with alcohol-related HCC.

ARID1A and ARID1B are two crucial and mutually exclusive subunits of the SWItch/Sucrose Non-fermentable (SWI/SNF) ATPase-powered nucleosome remodelling complex, which is involved in regulation of gene expression by controlling promoter accessibility. Interestingly, similar inactivating mutations in ARID1A, and its role as a tumor suppressor, has been reported in several malignancies, including ovarian, colorectal, and gastric cancer [39, 40, 41, 42]. On the other hand, ARID2 is a subunit of the polybromo- and BRG1-associated (PBAF) remodeling complex, which is implicated in the control of ligand-dependent transcription by nuclear receptors. In addition to these studies, Li et al. also found mutations in ARID2 in 18.6% of 33 HCCs analyzed by exome sequencing [43], which was further validated in an additional set of 106 tumors. Interestingly, both ARID1A [38] and ARID2 [43] mutations have been associated with the presence of CTNNB1 mutations, which are some of the most prevalent mutations in HCCs and are a hallmark of WNT pathway activation. ARID2 mutations and TP53 mutations were also shown to be mutually exclusive. ARID2 mutations have been predicted to result in a loss of function of the corresponding protein, predominantly through alteration of the Zn-finger motif of the DNA-binding domain, thus suggesting its role as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in HCC. With the data available to date, de-regulation of ARID1/2 signaling appears to affect 6–18% of HCC samples.

Differentiation and Development

Notch signaling pathway: The Notch pathway is a highly conserved signaling module present in most multicellular organisms. It plays an important role in cell-cellcommunications and participates in the regulation of multiple cell differentiation processes during embryonic development and stem/progenitor cell staging [44, 45]. In the liver, Notch acts in a temporal- and dose-dependent manner to coordinate biliary fate and morphogenesis [46]. Unlike most pathways, Notch signaling requires direct cell-to-cell interaction to ensure its proper activation. In human cancer, activating mutations and translocations affecting NOTCH1 is a characteristic feature of acute lymphoblastic leukemias [47]. In solid tumors, activation of Notch has been described in lung and prostate cancer [48, 49], although other reports also suggest the potential tumor suppressor activity of this pathway [50]. Thus, data regarding its role in cancer is contradictory. Two studies have demonstrated that NOTCH1 overexpression inhibits HCC cell growth by promoting cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [51, 52]. In contrast, there seems to be growing evidence suggesting an oncogenic role for Notch activation in hepatocarcinogenesis [53]. Significant over-expression of NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 was detected through immunohistochemistry in 60 HCCs [54]. In addition, the same study demonstrated that depletion of NOTCH3 by specific shRNAs increased p53 expression and enhanced doxorubicin-sensitivity by promoting apoptosis. Moreover, considering the important role of HBV X protein (HBx) in the development of HCC, a recent study found that HBx upregulates key molecules in Notch signaling (NOTCH1, HES1, and JAGGED1) [55]. This finding suggests that Notch activation may be one of the mechanisms by which HBx promotes HCC progression. These contradictory data for the role of the Notch cascade in solid tumors may be due to a high context-dependency.

Hedgehog signaling pathway: Hh signaling is required for embryogenesis and regulation of a variety of essential functions, from differentiation to regeneration, as well as in stem cell biology, through control of cellular proliferation, apoptosis, and migration. It is activated by the interaction of Hh ligands (i.e., sonic, indian, and dessert hedgehog) with the transmembrane Smoothened (SMO) receptor, resulting in nuclear translocation of Gli and transcriptional activation of target genes (fig. 1). Hh signaling targets include β-catenin, FGF, IGF2, EGF, BCl-2, and different cyclins, along with Hh negative regulators such as PTCH and HHIP. In diseased livers, the Hh pathway promotes hepatic regeneration; however, excessive or continuous activation of Hh has been shown to halt successful regeneration and contribute to liver fibrosis [56]. In HCC, the initial findings demonstrated aberrant over-expression of GLI1 and SMO together with down-regulation of HHIP in a subset of HCCs [57]. Furthermore, inhibition of the Hh pathway by cyclopomine, a steroid alkaloid that binds to and blocks SMO, significantly inhibited cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, and repressed the expression of two of the Gli-related target genes, c-Myc and cyclin D1. Interestingly, a recent paper showed that Hh inhibition in a mouse model of HCC through the use of a selective antagonist, GDC-0449, led to the regression of both liver fibrosis and HCC, even in advanced stages of the disease [58].

Hippo signaling pathway: The hippo pathway is an evolutionary conserved cascade that plays an essential role in the control of organ size and cell contact inhibition by regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis. During recent years, growing evidence has pointed towards an oncogenic role for this pathway in human cancer, including HCC [59]. While the key components and upstream regulators of the hippo pathway (e.g., FAT, NF2, and FDM6) are mostly considered to participate as tumor suppressors, downstream mediators such as TAZ, YAP, and TEADs are mostly involved in oncogenic events. In general terms (fig. 1), the initial hippo kinases complex, formed by MST1, MST2, and its scaffold protein (SAV1), activates the Lats1/2-Mob1 complex, which, in turn, phosphorylates the transcription factors YAP and TAZ, preventing their translocation to the nucleus and consequent target gene transcription. Several studies have demonstrated that MST1/2 double knockout mice demonstrate liver outgrowth and HCC [60, 61, 62]. This is consistent with the results obtained in YAP-overexpressing transgenic mice, which also presented with a similar phenotype [63]. In addition, two other studies have demonstrated that MST1/2 plays an important role in regulating the liver progenitor/stem cell compartment in adult liver. Interestingly, approximately 30% of HCCs present with low levels of phospho-YAP and an inactive cleaved form of MST1 is present in the majority of these cases [62]. Moreover, a heterozygous deletion of YAP was able to suppress development of HCC caused by NF2 inactivation [64]. Altogether, these findings indicate that inhibition of YAP by MST1/2 can be considered as an important pathway for HCC suppression.

Inflammation-related Pathways

Solid evidence supports the causal connection between chronic inflammation and cancer. In HCC, close to 80% of patients develop tumors against a background of chronic liver inflammation; however, little is known about the specific molecular mechanisms underlying this process. Additional events also present in cirrhosis, such as persistent cell regeneration, may also contribute to malignant transformation in this context. A recent publication has revealed the promoting effect of translocation of intestinal microbiota to the liver through activation of toll like receptor 4 (TRL4) in the advanced stages of HCC [65]. This study included numerous animal models (i.e., TLR4 genetic inactivation, gut sterilization and long-term treatment with low doses of LPS), where chronic liver injury was modeled using diethylnitrosamine and carbon tetrachloride. The authors demonstrated that once TLRs recognize microbial ligands, like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), the NF-kβ pathway is activated, promoting the secretion of inflammatory molecules, such as TNF-α and cytokines. These molecules regulate multiple reactions in resident liver cells (e.g., hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and particularly stellate cells), which are responsible for hepatic injury, a step that precedes HCC development. Furthermore, these results are consistent with previous data that showed that activation of NF-kβ mediates liver oncogenesis in liver-specific mice that over-expressed lymphotoxin [66]. This model developed chronic hepatitis, followed by HCC, at 12 months of age. However, once lymphotoxin expression was blocked, the chronic inflammatory hepatitis was reverted, also preventing the onset of HCC. These data further demonstrate the importance of an inflammatory environment in the initial steps of HCC development.

Autophagy

Autophagy is a conserved lysosomal degradation pathway responsible for maintaining cellular homeostasis through recognition and turnover of damaged proteins and organelles. This pathway has been implicated in different, and sometimes contradictory, processes capable of inducing both cell survival and death. Autophagy can be divided into constitutive autophagy, which is necessary for intracellular recycling and metabolic regulation, and stress-related autophagy, which is required for elimination of damaged intracellular components generated by cellular stress. Interestingly, numerous reports have described activation of autophagy by many anti-cancer therapies currently in use [67]. Hence, its role in carcinogenesis and its crosstalk with anti-cancer drugs is currently being evaluated. Constitutive autophagy is suppressed in many tumors (i.e., prostate, breast, ovarian); allelic losses of one of the genes essential to this process (BECLIN1) is one of the main molecular mechanisms known to underlie this abrogation of autophagy [68]; BECLIN1 knockout mice (beclin1 +/-) also develop HCC [69]. Conversely, another study demonstrated that sorafenib up-regulates autophagy by inducing autophagosome formation both in vitro and in vivo, thus protecting malignant cells from death [70]. Overall, these preliminary reports underscore a potential role for autophagy in the progression of HCC and its response to therapy. Further exploration of this cascade will delineate its relevance as a source of novel therapeutic targets.

References

- 1.Hoshida Y, Toffanin S, Lachenmayer A, Villanueva A, Minguez B, Llovet JM. Molecular classification and novel targets in hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advancements. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:35–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7385–7392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:674–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tovar V, Alsinet C, Villanueva A, et al. IGF activation in a molecular subclass of hepatocellular carcinoma and pre-clinical efficacy of IGF-1R blockage. J Hepatol. 2010;52:550–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueki T, Fujimoto J, Suzuki T, Yamamoto H, Okamoto E. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor c-met proto-oncogene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1997;25:862–866. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaposi-Novak P, Lee JS, Gomez-Quiroz L, Coulouarn C, Factor VM, Thorgeirsson SS. Met-regulated expression signature defines a subset of human hepatocellular carcinomas with poor prognosis and aggressive phenotype. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1582–1595. doi: 10.1172/JCI27236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villanueva A, Chiang DY, Newell P, et al. Pivotal role of mTOR signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;1356:1972–83. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.08.008. 1983 e1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1995–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanabe KK, Lemoine A, Finkelstein DM, et al. Epidermal growth factor gene functional polymorphism and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. JAMA. 2008;299:53–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miura H, Miyazaki T, Kuroda M, et al. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 1997;27:854–861. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, et al. Halting the interaction between vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors attenuates liver carcinogenesis in mice. Hepatology. 2004;39:1517–1524. doi: 10.1002/hep.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poon RT, Ho JW, Tong CS, Lau C, Ng IO, Fan ST. Prognostic significance of serum vascular endothelial growth factor and endostatin in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1354–1360. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casanovas O, Hicklin DJ, Bergers G, Hanahan D. Drug resistance by evasion of antiangiogenic targeting of VEGF signaling in late-stage pancreatic islet tumors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiang DY, Villanueva A, Hoshida Y, et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6779–6788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawey ET, Chanrion M, Cai C, et al. Identification of a therapeutic strategy targeting amplified FGF19 in liver cancer by Oncogenomic screening. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villanueva A, Llovet JM. Targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1410–1426. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi K, Sakamoto M, Yamasaki S, Todo S, Hirohashi S. Akt phosphorylation is a risk factor for early disease recurrence and poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:307–312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lachenmayer A, Alsinet C, Savic R, et al. Wnt-pathway activation in two molecular classes of hepatocellular carcinoma and experimental modulation by sorafenib. Clin Cancer Res. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson BG, Roberts CW. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:481–492. doi: 10.1038/nrc3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane AA, Chabner BA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5459–5468. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolden JE, Peart MJ, Johnstone RW. Anticancer activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:769–784. doi: 10.1038/nrd2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prince HM, Bishton MJ, Harrison SJ. Clinical studies of histone deacetylase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3958–3969. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boumber Y, Issa JP. Epigenetics in cancer: what's the future? Oncology. 2011;25:220–226. 228 (Williston Park) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lachenmayer A, Toffanin S, Cabellos L, et al. Combination therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: additive preclinical efficacy of the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat with sorafenib. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1343–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu LM, Yang Z, Zhou L, et al. Identification of histone deacetylase 3 as a biomarker for tumor recurrence following liver transplantation in HBV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Di Fazio P, Schneider-Stock R, Neureiter D, et al. The pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat inhibits growth of hepatocellular carcinoma models by alternative pathways of apoptosis. Cell Oncol. 2010;32:285–300. doi: 10.3233/CLO-2010-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu YL, Yang PM, Shun CT, Wu MS, Weng JR, Chen CC. Autophagy potentiates the anti-cancer effects of the histone deacetylase inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Autophagy. 2010;6:1057–1065. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu YS, Kashida Y, Kulp SK, et al. Efficacy of a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor in murine models of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;46:1119–1130. doi: 10.1002/hep.21804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pathil A, Armeanu S, Venturelli S, et al. HDAC inhibitor treatment of hepatoma cells induces both TRAIL-independent apoptosis and restoration of sensitivity to TRAIL. Hepatology. 2006;43:425–434. doi: 10.1002/hep.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venturelli S, Armeanu S, Pathil A, et al. Epigenetic combination therapy as a tumor-selective treatment approach for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;109:2132–2141. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang JX, Li DQ, He AR, et al. Synergistic inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma growth by cotargeting chromatin modifying enzymes and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases. Hepatology. 2012;55:1840–1851. doi: 10.1002/hep.25566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujimoto A, Totoki Y, Abe T, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of liver cancers identifies etiological influences on mutation patterns and recurrent mutations in chromatin regulators. Nat Genet. 2012;44:760–764. doi: 10.1038/ng.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guichard C, Amaddeo G, Imbeaud S, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and focal copy-number changes identifies key genes and pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:694–698. doi: 10.1038/ng.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan B, Wang TL, Shih Ie M. ARID1A, a factor that promotes formation of SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling, is a tumor suppressor in gynecologic cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6718–6727. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones S, Li M, Parsons DW, et al. Somatic mutations in the chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A occur in several tumor types. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:100–103. doi: 10.1002/humu.21633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones S, Wang TL, Shih Ie M, et al. Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science. 2010;330:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1196333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1532–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li M, Zhao H, Zhang X, et al. Inactivating mutations of the chromatin remodeling gene ARID2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:828–829. doi: 10.1038/ng.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radtke F, Raj K. The role of Notch in tumorigenesis: oncogene or tumour suppressor? Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:756–767. doi: 10.1038/nrc1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaret KS. Genetic programming of liver and pancreas progenitors: lessons for stem-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrg2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zong Y, Panikkar A, Xu J, et al. Notch signaling controls liver development by regulating biliary differentiation. Development. 2009;136:1727–1739. doi: 10.1242/dev.029140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santagata S, Demichelis F, Riva A, et al. JAGGED1 expression is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and recurrence. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6854–6857. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Westhoff B, Colaluca IN, D'Ario G, et al. Alterations of the Notch pathway in lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22293–22298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907781106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicolas M, Wolfer A, Raj K, et al. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in mouse skin. Nat Genet. 2003;33:416–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi R, An H, Yu Y, et al. Notch1 signaling inhibits growth of human hepatocellular carcinoma through induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:8323–8329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang C, Qi R, Li N, et al. Notch1 signaling sensitizes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by inhibiting Akt/Hdm2-mediated p53 degradation and up-regulating p53-dependent DR5 expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16183–16190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Villanueva A, Alsinet C, Yanger K, et al. Notch signaling is activated in human hepatocellular carcinoma and induces tumor formation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Giovannini C, Gramantieri L, Chieco P, et al. Selective ablation of Notch3 in HCC enhances doxorubicin's death promoting effect by a p53 dependent mechanism. J Hepatol. 2009;50:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang F, Zhou H, Yang Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus X protein promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by modulation of the Notch signaling pathway. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:1170–1176. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Omenetti A, Choi S, Michelotti G, Diehl AM. Hedgehog signaling in the liver. J Hepatol. 2011;54:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patil MA, Zhang J, Ho C, Cheung ST, Fan ST, Chen X. Hedgehog signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:111–117. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.1.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Philips GM, Chan IS, Swiderska M, et al. Hedgehog signaling antagonist promotes regression of both liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in a murine model of primary liver cancer. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23943. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan SW, Lim CJ, Chen L, et al. The Hippo pathway in biological control and cancer development. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:928–939. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu L, Li Y, Kim SM, et al. Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1437–1442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911427107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Song H, Mak KK, Topol L, et al. Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1431–1436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911409107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou D, Conrad C, Xia F, et al. Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, et al. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang N, Bai H, David KK, et al. The Merlin/NF2 tumor suppressor functions through the YAP oncoprotein to regulate tissue homeostasis in mammals. Dev Cell. 2010;19:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dapito DH, Mencin A, Gwak GY, et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haybaeck J, Zeller N, Wolf MJ, et al. A lymphotoxin-driven pathway to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.White E, DiPaola RS. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5308–5316. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, et al. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics. 1999;59:59–65. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin 1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1809–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shimizu S, Takehara T, Hikita H, et al. Inhibition of autophagy potentiates the antitumor effect of the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:548–557. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]