Abstract

This study examined the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquent behavior across two time points in a sample of 303 maltreated and 151 comparison adolescents aged 9–13 years at enrollment. The first aim was to examine the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency for the total sample and then to test for gender differences using multiple-group models. The second aim was to examine the interaction effect of pubertal timing and maltreatment on delinquency as well as gender differences for this interaction effect. Results showed that earlier pubertal timing was related to higher delinquency and this relationship was not significantly different for males and females. Maltreatment did not moderate the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency for the total sample; however, there was evidence of a three-way interaction. These findings highlight the need to examine contextual factors that may affect the amplification and direction of these relationships.

Keywords: pubertal timing, delinquency, maltreatment, gender differences

Although a number of studies find early pubertal timing to be associated with a number of externalizing problems such as delinquency, substance use, and behavior problems (Caspi, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, 1993; Dick, Rose, Pulkkinen, & Kaprio, 2001; Dorn, Susman, & Ponirakis, 1999; Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & McBride-Murray, 2002; Graber, Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Brooks-Gunn, 1997), there is not consensus that puberty affects all externalizing problems or that it affects males and females equivalently. There is substantial evidence that early maturation is associated with high levels of externalizing behavior, bullying, truancy, disruptive behavior, and violent behavior (Flannery, Rowe, & Gulley, 1993; Ge et al., 2002; Graber et al., 1997; Kaltiala-Heino, Marttunen, Rantanen, & Rimpela, 2003; Obeidallah, Brennan, Brooks-Gunn, & Earls, 2004). However, there are a limited number of studies that have examined the outcome of delinquency specifically, and the results are mixed. Additionally, few studies have examined gender differences in the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency (Flannery et al., 1993; Lynne, Graber, Nichols, Brooks-Gunn, & Botvin, 2007); most research has been limited to single-gender samples (Caspi et al., 1993; Cota-Robles, Neiss, & Rowe, 2002; Felson & Haynie, 2002; Haynie, 2003; Williams & Dunlop, 1999).

Theoretical Explanations for the Relationship between Pubertal Timing and Delinquency

Several theories have been proposed to explain the association between pubertal development and delinquent behavior. Early maturers may be drawn into risky behavior such as delinquency by older adolescents who judge the individual by their external appearance of maturity, not by their chronological age. Alternatively, a mismatch of external appearance and cognitive development may lead to norm violating behaviors and delinquency at an earlier age than for those individuals who mature later (Peskin, 1973). Adolescents are reaching biological maturity earlier in contemporary society than in past eras but the corresponding social maturity is not expected until an older age resulting in a “maturity gap” (Moffitt, 1993). Delinquency may be a consequence of this “maturity gap” when adolescents try to adjust to the difference between their biological and social maturity. Both of these explanations propose that the effect of pubertal timing will be more detrimental for early maturers than on-time or late maturers.

Another theory posits that both early and late pubertal timing put an adolescent at risk for problem behavior. When an adolescent does not mature at the same age as his or her peers it creates added stresses that may increase delinquent behaviors as a coping mechanism (Petersen & Taylor, 1980). Therefore off-time development (developing earlier or later than peers) in itself may increase risk for delinquency. Thus, while some theories suggest peers influence the delinquent behavior of early maturers, other explanations point to the individual’s ability to cope with social pressures and expectations.

There is some evidence to support these theoretical explanations; delinquency is associated with early timing in some studies but with off-timing in other studies. Both cross-sectionally and across one year early maturing girls were found to have the highest levels of delinquency (Caspi et al., 1993; Haynie, 2003). However, Caspi and colleagues (1993) also found that at age 15 early and on-time girls both exhibited more delinquency than late maturing girls. In studies with all male samples, one found early maturation to be associated with higher levels of violent and non-violent delinquency (Cota-Robles et al., 2002), while another found both early and late timing (“off-timing”) were related to the highest levels of delinquent behavior (Williams & Dunlop, 1999). Results from studies that included both genders found bullying, truancy, and delinquency to be higher in both early maturing boys and girls compared to on-time or late maturing individuals (Flannery et al., 1993; Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & McBride-Murray, 2006; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2003). Ge and colleagues (2006) examined in particular whether there was a nonlinear or “off-time” effect of pubertal timing on internalizing and externalizing problems. Using three timing groups (early, on-time, and late) they found no evidence of an “off-time” effect, only early timing was associated with problem behavior. However, given that other studies have found “off-time” effects there is need for further clarification.

Pubertal Timing and Contextual Stressors

While there is some incongruity as to whether early and/or late pubertal timing is a risk for delinquency, evidence supports the contextual amplification of this relationship. For example, the effects of early development were accentuated for those girls who attended mixed-gender schools (Caspi et al., 1993), affiliated with deviant peers (Felson & Haynie, 2002; Haynie, 2003), or experienced neighborhood disadvantage (Obeidallah et al., 2004). These studies indicate that certain contextual conditions or experiences may increase the risk of adjustment problems for early maturing adolescents.

One such contextual experience that has seen limited investigation is child maltreatment. Maltreatment is an exceptionally stressful experience that single-handedly impacts a number of areas of functioning. More adolescents with a history of maltreatment have been found to engage in delinquent behavior than those without a history of maltreatment (Bolton, Reich, & Gutierres, 1977; McCord, 1983; Zingraff, Leiter, Myers, & Johnson, 1993). This may be due to reduced stress reactivity in the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis demonstrated by maltreated youth (De Bellis & Putnam, 1994; Hart, Gunnar, & Cicchetti, 1995; Tarullo & Gunnar, 2006) which in turn is associated with externalizing problems (McBurnett, Lahey, Rathouz, & Loeber, 2000; Popma et al., 2006). Social learning factors may also account for the association between maltreatment and delinquency. For example, parents who maltreat their children likely provide models of deviant or aggressive behaviors and the appropriateness of such behavior (Widom, 1989). Child maltreatment may alter an individual’s style of coping in response to stress. Studies have found that maltreated individuals are more likely to rely on maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance and wishful thinking (Bal, Crombez, Van Oost, & Debourdeaudhuij, 2003; Leitenberg, Gibson, & Novy, 2004) making them more vulnerable to subsequent stressful experiences.

Additionally, the general strain literature posits that individuals who face greater adversity often manifest aggressive tendencies in response to the strain they experience. Aggressive tendencies may be a result of maladaptive coping to adversity and often lead to later antisocial behaviors including delinquency (Agnew, 1992). Pubertal development is a difficult transition for some individuals and specifically being early or late may be particularly stressful. An adolescent who has been maltreated may be more likely to deal with the stress of pubertal development less adaptively than one without maltreatment experience They may also have more difficulty dealing with the additional stressor and be more likely to engage in delinquent behaviors as a result (Compas, Ey, & Grant, 1993; Rutter, 1991; Simmons, Burgeson, Carlton-Ford, & Blythe, 1987). Subsequently it is expected that adolescents who have a history of maltreatment and are off-time in their pubertal development are likely to be at the highest risk for behavior problems. There is a significant gap in the extant research as to the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquent behavior in adolescents with the experience of maltreatment.

The Current Study

Overall, the empirical literature provides evidence that early pubertal timing for both genders is associated with increased delinquent behavior. However, some findings suggest an association between early timing and delinquency only for females, or between early and late timing and delinquent behavior only for males. The research on these relationships is dominated by the use of female samples, leaving limited evidence regarding males. Therefore, the first aim of this study was to clarify whether a linear or nonlinear model was the best explanation of the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquent behavior. A significant nonlinear effect would support a curvilinear relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency. Presumably this would indicate that both early and late pubertal timing would be associated with higher delinquency than on-time pubertal timing. However if no significant nonlinear effect was found then the linear effect would be the best explanation of the data. This was examined for the total sample and then gender differences were examined. Based on the literature it was expected that early timing would be related to higher delinquency for both males and females. However, due to the conflicting findings from different studies, it was uncertain whether late timing would also be related to delinquency for males. In addition, based on the extant research, a hypothesis could not be developed regarding whether the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency would be significantly different between genders.

Both off-time pubertal timing and maltreatment have individually been found to increase the risk for delinquency and violent behavior. This association warrants investigation into whether both off-time pubertal development and experience of maltreatment interact to create a double vulnerability above and beyond the risk conferred by each factor alone. A void exists regarding the relationship between pubertal development and delinquency in maltreated adolescents. It seems pertinent to examine this combination of variables in order to determine the conditions which may substantially increase risk for delinquent behavior. Thus, the second aim of this study was to examine the interaction between maltreatment and pubertal timing to determine whether maltreatment moderated the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency. Lastly, a three-way interaction between pubertal timing, maltreatment, and gender was examined. Because maltreatment has not yet been examined as a moderator of the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency there was no evidence on which to base hypothesized relationships. However, given the evidence linking maltreatment to higher delinquency it was expected to amplify the effects of off-time pubertal timing on delinquent behavior.

These questions were examined in an ethnically diverse sample of male and female adolescents from a large urban area. Approximately two-thirds of the sample had substantiated reports of maltreatment as determined by Children and Family Services. The varied ethnic composition and even split between genders provided an opportunity to supplement and expand the existing research to more varied populations and clearly distinguish gender differences.

Research Design and Methods

Participants

The present study used data from Time1 and 2 of an ongoing longitudinal study examining the effects of maltreatment on adolescent development. The sample comprised 454 adolescents at Time 1. The first and second assessments took place approximately 1 year apart and 86% of the initial sample completed the second interview. Of the 62 participants who were not seen at Time 2, 19 refused to continue in the study, 12 moved out of the country, and 31 were avoidant or difficult to schedule. The participants who only completed Time 1 were compared with those who completed both Time 1 and Time 2 on various demographic characteristics. Tests of mean differences on these variables indicated that the groups only differed significantly on their group status (maltreated versus comparison) with 82.5 % of the maltreated group versus 94% of the comparison group completing both time points.

Recruitment

The participants who comprised the maltreatment group (n = 303) were recruited from active cases in the Children and Family Services (CFS) of a large west coast city. The inclusion criteria were: (1) a new substantiated referral to CFS in the preceding month for any type of maltreatment (e.g. neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse); (2) child age of 9–12 years; (3) child identified as Latino, African-American, or Caucasian (non-Latino); and (4) child residing in one of 10 zip codes in a designated county at the time of referral to CFS. With the approval of CFS and the Institutional Review Board of the affiliated university, potential participants were contacted via postcard and asked to indicate their willingness to participate. Contact via mail was followed up by a phone call.

The comparison group (n = 151) was recruited using names from school lists of children aged 9–12 years residing in the same 10 zip codes as the maltreated sample. Caretakers of potential participants were sent a postcard and asked to indicate their interest in participating which was followed up by a phone call.

Upon enrollment in the study both the maltreatment and comparison groups were compared on a number of demographic variables. The two groups were similar on age, (M = 10.93 years, SD = 1.16), gender (53% male), ethnicity (38% African American, 39% Latino, 12% Biracial, and 11% Caucasian), and neighborhood characteristics (based on Census block information). However, they were different in terms of living arrangements. In the comparison group 93% lived with a biological parent, whereas this was the case for only 52% of the maltreated group. The remainder were living in foster care, which is not unusual for those adolescents involved with social services. At the time of the present study only the enrollment criteria for maltreatment was available and efforts are currently in process to abstract detailed histories from the CFS records. Therefore for this study maltreatment experience was dichotomized as maltreated versus comparison.

Procedure

Assessments were conducted at an urban research university. After assent and consent were obtained from the adolescent and their caretaker, the adolescent was administered an array of questionnaires and tasks during a four-hour protocol. The measures used in the following analyses represent a subset of the questionnaires administered during the protocol, which also included hormonal, cognitive, and behavioral measures. Both the child and caretaker were paid for their participation according to the National Institutes of Health Normal Volunteer Program.

Measures

Pubertal Development

Tanner Stages

Pubertal stage was measured using the adolescent’s self-report on the Tanner stages. Five stages of pubertal development are represented by sets of serial line drawings that depict the development of two different secondary sexual characteristics from prepubertal (stage = 1) to postpubertal (stage = 5) (Morris & Udry, 1980). Female drawings are of breast development and pubic hair growth whereas male drawings are of genital development and pubic hair growth. Self-report on Tanner stages are highly correlated with physician assessment and sufficient when rough estimation of pubertal stage is adequate (Dorn, Susman, Nottelmann, Inoff-Germain, & Chrousos, 1990). Scores on each drawing (breast/genital and pubic hair) were used as separate indicators of pubertal development.

Pubertal Development Scale

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) is a measure of physical changes associated with pubertal development. It was developed as an alternative to physician rating measures and has shown to have adequate reliability and validity (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). On a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (has not yet started) to 4 (has completed) each subject is asked to indicate the level of development on each of the physical changes. Four items were used for both males and females (height spurt, body hair, skin changes, deepening of voice/breast growth). For the purpose of the present study the four items were averaged to retain the original metric of the scale.

Pubertal Timing

When the degree of physical development is standardized within same-age peers, the resulting score can be used as an index of pubertal timing (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001). For the present study the scores on each of the Tanner Stage ratings (breast/genital and pubic hair) and the average of the PDS scores were standardized within each age cohort (e.g. 9, 10, 11) and gender. The resulting z-score for each measure had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 with higher scores indicating earlier maturation relative to peers. This continuous pubertal timing variable was computed separately for Time 1 and Time 2 pubertal development.

Delinquency

Adolescent Delinquency Questionnaire

Participants reported delinquent behavior within the past 12 months via 23 items from the self-report Adolescent Delinquency Questionnaire (ADQ; adapted from Huizinga & Morse, 1986). Computerized administration was used to ensure participant confidentiality. For the present study, three scales were used: status offenses (6 items, e.g. “run away from home”, α = .74), person offenses (7 items, e.g. “carried a hidden weapon”, α = .83), and property offenses (10 items, e.g. “damaged or destroyed someone else’s property on purpose”, α = .92). The items on each factor were summed to yield a composite score for that scale and square root transformations were applied to each composite scale score to reduce skewness.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using structural equation modeling with Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation in Amos 5.0 (J.L. Arbuckle, 2003). To examine whether the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency was nonlinear, a model was specified in which both the latent variable of pubertal timing and its quadratic term had direct effects on a latent variable of delinquency. The standardized scores on Tanner breast/genital stage, Tanner pubic hair, and PDS were used as manifest variables for the latent variable of pubertal timing while the transformed scores on the status, person, and property offence scales were used as the indicators of the delinquency latent variable. The quadratic term was specified in the model according to the two-step technique outlined by Ping (1996). In order to accurately estimate the nonlinear effects, the factor loadings and error variances of the constituent variables of the latent quadratic term must be fixed as functions of the linear terms. This is accomplished by first estimating the factor loadings and error variances for the indicators of the linear latent variable in the measurement model. Then the nonlinear indicators of the quadratic latent variable are created as products of the indicators of the linear latent variable. Thus, all the manifest quadratic terms were included in the model while the error variances and factor loadings were fixed to the values obtained from the computations with the linear manifest variables. To test the cross-sectional relationships two separate models were fit: one in which the measures of pubertal timing and delinquency were both from Time 1 and a second in which the measures of pubertal timing and delinquency were both from Time 2. To test for the longitudinal effect, the measure of pubertal timing was taken from Time 1, while the measure of delinquency was taken from Time 2. Maltreatment/comparison group, gender, ethnicity, and household income (as a proxy for SES) were included as covariates. A significant parameter coefficient for the path from the quadratic term to delinquency would indicate a nonlinear effect.

If the quadratic term was not significant a linear model was then tested. The same three models were carried forward, with the exclusion of the quadratic term. Additionally, a full model was estimated in which relationships between Time 1 and Time 2 pubertal timing and delinquency were included. Main effects were modeled between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 1 delinquency, between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency, and between Time 2 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency (accounting for Time 1 delinquency). Additionally, reciprocal relationships between pubertal timing and delinquency at Time 1 and Time 2 were included. Covariates included maltreatment/comparison group, gender, ethnicity, and household income (as a proxy for SES).

Interaction effects were tested by multiple group analysis between gender and then maltreatment and comparison groups using the full model. First, an unconstrained model was fit simultaneously to both groups; this model provided a basis from which to compare more restricted models. Next, the measurement weights (factor loadings) were constrained to be equal across groups to establish the measurement invariance between the groups. Lastly the structural weights (pubertal timing to delinquency) were constrained to be equal across groups. A significant change in the χ2 provided evidence that one or more of the parameters differed significantly between the groups, indicating an interaction effect. If a significant χ2 difference emerged then each structural restriction was lifted in turn to determine which one(s) were responsible for the decrement in model fit. The covariates were the same as in the previous models except that gender was excluded for the multiple group models between genders and maltreatment group was excluded for the multiple group models between the maltreatment and comparison groups.

Lastly, to test for three-way interactions a multiple group analysis was completed by splitting the sample into maltreated males, maltreated females, comparison males and comparison females. Each group was entered into a 2-group model to allow for all possible contrasts (maltreated males vs. maltreated females, comparison males vs. comparison females, maltreated males vs. comparison males, maltreated females vs. comparison females, maltreated males vs. comparison females, comparison males vs. maltreated females). As in the previous multiple group analyses, first an unrestricted model was fit simultaneously to both groups, then the measurement weights were restricted to be equal across groups, then the structural weights were restricted. A significant decrement in the model fit as indicated by the chi-square difference test indicated that one or more of the parameters was moderated. Each structural restriction was released in turn to determine which one(s) were contributing to the decrement in model fit.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Missing Data Imputation

In order to obtain the maximum amount of data for the ADQ, missing data were imputed at the first order which is used for item level missingness, instances in which a particular item on a measure was not answered. The NORM (Schafer, 1999) software program was used to impute missing data using an Estimation-Maximization (EM) algorithm (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977; Orchard & Woodbury, 1972). Imputation replaces missing data with an estimated value “representing a distribution of possibilities” through iteration processes. The missingness rate for the ADQ variables at Time 1 and 2 ranged from .02% to 4.6%. At Time 1 there were nine cases with no data on the ADQ due to computer malfunction and 2 cases missing more than 74%. This resulted in 443 cases with data for the Time 1 ADQ and 391 for Time 2 ADQ. As with most prospective longitudinal studies, data for some participants were not available for both times of assessment. Analyzing only those cases with complete data has the potential to produce biased results; therefore the total sample was used for analyses (Muthén, Kaplan, & Hollis, 1987). Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) (J.L. Arbuckle, 1996) was used to handle variable level missingness and longitudinal missingness across time. This procedure does not impute data but breaks down the likelihood function into components based on patterns of missing data, allowing estimation to proceed using all available data. To implement FIML, the intercepts of observed variables and means of the latent factors were estimated in the model.

Bivariate Relationships

Intercorrelations were computed between the variables of interest (Table 1). Significant correlations were found among all the pubertal timing variables for Time 1 (rs = .34 to .63, p < .01) and Time 2 data (rs = .45 to .68, p < .01). The three delinquency scales were found to have significant intercorrelations for both Time 1 (rs =.75 to .81, p < .01) and Time 2 data (rs =.58 to .74, p < .01).

Table 1.

Correlations between Time 1 and Time 2 puberty and delinquency variables

| T1 Pubertal timing

|

T1 Delinquency

|

T2 Pubertal timing

|

T2 Delinquency

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBG (n=447) | TPH (n=447) | PDS (n=452) | Status offences (n=443) | Person offences (n=443) | Property offences (n=443) | TBG (n=391) | TPH (n=391) | PDS (n=391) | Status offences (n=391) | Person offences (n=391) | Property offences (n=391) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| T1 Pubertal timing | ||||||||||||

| TBG | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| TPH | .63** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| PDS | .35** | .34** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| T1 Delinquency | ||||||||||||

| Status offences | .16** | .15** | .15** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Person offences | .07 | .09 | .12* | .76** | 1.00 | |||||||

| Property offences | .06 | .05 | .10* | .75** | .81** | 1.00 | ||||||

| T2 Pubertal timing | ||||||||||||

| TBG | .44** | .39** | .30** | .12* | .07 | .05 | 1.00 | |||||

| TPH | .39** | .43** | .30** | .10 | .06 | .01 | .68** | 1.00 | ||||

| PDS | .29** | .32** | .40** | .12* | .02 | .03 | .45** | .46** | 1.00 | |||

| T2 Delinquency | ||||||||||||

| Status offences | .12* | .16** | .07 | .41** | .32** | .23** | .24** | .19** | .24** | 1.00 | ||

| Person offences | .11* | .11* | .09 | .43** | .46** | .30** | .16** | .13* | .18** | .58** | 1.00 | |

| Property offences | .04 | .03 | .03 | .37** | .38** | .27** | .13* | .07 | .12* | .63** | .74** | 1.00 |

| Maltreatment | .05 | .04 | .00 | .14** | .09 | .08 | .03 | −.01 | −.03 | .09 | .07 | .07 |

| Gender | .00 | .00 | .00 | −.08 | −.14** | −.08 | .00 | .00 | .00 | −.09 | −.14** | −.08 |

Note: TBG= Tanner breast/genital stages; TPH=Tanner pubic hair stages; PDS=Pubertal Development Scale; all have been standardized within age and gender to obtain indices of pubertal timing; maltreatment =1, comparison =0; male=0, female =1;

p<.05,

p<.01

Distribution of Pubertal Stage

The percentage of participants in each Tanner stage was examined to verify that there were an adequate number who had entered puberty. As Table 2 shows, based on Tanner genital stage approximately 78% of males had entered puberty and based on Tanner breast stage approximately 66% of females had entered puberty.

Table 2.

Percent of participants in each Tanner stage of development by gender

| Genital | Breast | Pubic hair | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Males (%) | Females (%) | Males (%) | Females (%) | |

|

|

|

|

||

| Tanner 1 (pre-pubertal) | 20.8 | 33.5 | 22.5 | 36.3 |

| Tanner 2 | 41.3 | 50.5 | 40.8 | 36.3 |

| Tanner 3 | 26.3 | 12.7 | 22.9 | 19.8 |

| Tanner 4 | 9.6 | 2.4 | 10.8 | 5.7 |

| Tanner 5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

Note: percentages do not add up to 100 because there are some cases with missing data

Mean Differences in Delinquency

Analysis of covariance was used to examine mean differences between the groups of interest (maltreatment vs. comparison; male vs. female) on the delinquency scales controlling for age, and race. For Time 1 delinquency there were mean differences between the maltreatment and comparison groups on status offenses F(443, 1) = 11.36, p<.01 and person offenses F(443,1) = 5.02, p<.05, with the maltreatment group being higher on both scales. For Time 2 delinquency there were mean differences between the maltreatment and comparison only for status offenses F(390, 1) = 6.80, p<.01 with the maltreatment group being higher. Between males and females there were group differences for Time 1 person offenses F(443, 1) = 9.63, p<.01, with males being higher. At Time 2 males were significantly higher than females on status F(390, 1) = 3.93, p<.05 and person offenses F(443, 1) = 8.01, p<.01.

Substantive Analyses

Pubertal Timing and Delinquency: “Off-time” versus “Early-timing”

The results showed that the parameter estimate between the latent quadratic variable and delinquency was not significant in any of the models, indicating that a nonlinear model was not a good explanation of the data1.

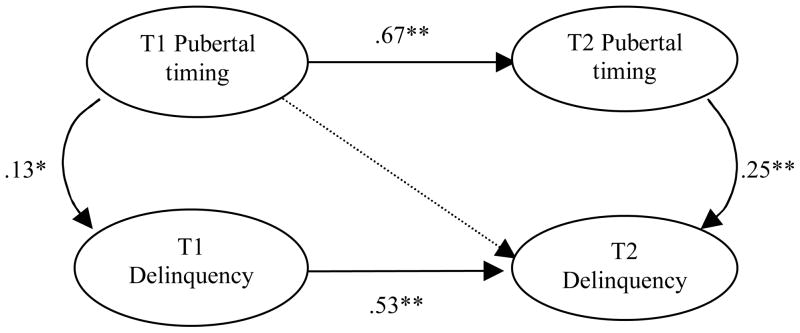

Because the quadratic term was not significant in the previous model, the models were re-estimated excluding the quadratic term. The Time 1 model showed a good fit to the data (χ2 = 23.90 (12), RMSEA = .05, CFI=.99). Parameter estimates indicated a significant relationship between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 1 delinquency (β = .13, p < .05). The direction of the regression coefficients indicated that earlier pubertal timing was related to higher levels of delinquency. The Time 2 model also showed a good fit to the data (χ2 = 31.12 (12), RMSEA = .06, CFI=.98) and there was a significant relationship between Time 2 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency (β = .20, p < .01). The model with Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency showed a good fit as well (χ2 = 16.69 (12), RMSEA = .03, CFI=.99) with a marginally significant relationship between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency (β = .12, p < .10). Additionally, the full model fit the data adequately (χ2 = 171.47 (59), RMSEA=.07, CFI=95) and showed significant relationships between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 1 delinquency (β = .13, p < .05), between Time 2 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency (β = .25, p < .01), between Time 1 and Time 2 pubertal timing (β = .67, p < .01), and between Time 1 and Time 2 delinquency (β = .53, p < .01). The marginally significant relationship found in the previous model between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency was no longer significant after controlling for Time 1 delinquency. Parameter estimates for the full model are shown in Figure 1 and Table 3.

Figure 1.

Full model with parameter estimates for the total sample

Note: manifest variables and covariates have been omitted for simplicity of presentation; dotted line is non-significant; *p<.05, **p<.01

Table 3.

Parameter estimates for the full model testing the relationships between pubertal timing and delinquency: Total sample and multiple group models by gender and maltreatment group

| Unstandardized estimates (SE)

|

Standardized estimates

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | Males | Females | Maltreatment | Comparison | Total sample | Males | Females | Maltreatment | Comparison | |

| Full Model | ||||||||||

| T1pubertal timing→T1delinquency | .31 (.14) | .43 (.20) | .09 (.16) | .34 (.17) | .09 (.27) | .13** | .16* | .04 | .13† | .03 |

| T1pubertal timing→T2delinquency | −.25 (.16) | −.25 (.18) | −.80 (.69) | −.25 (.24) | −.18 (.18) | −.13** | −.11 | −.56 | −.12 | −.11 |

| T1pubertal timing→T2pubertal timing | .69 (.07) | .53 (.09) | .89 (.12) | .80 (.09) | .49 (.11) | .67** | .50** | .90** | .73** | .49** |

| T2pubertal timing→T2delinquency | .47 (.15) | .34 (.16) | 1.07 (.71) | .37 (.21) | .70 (.20) | .25** | .16* | .73 | .20† | .41** |

| T1delinquency→T2delinquency | .42 (.04) | .52 (.06) | .26 (.06) | .42 (.05) | .30 (.05) | .53** | .63** | .34** | .53** | .51** |

Note: all parameter estimates are from unconstrained model;

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.10

Pubertal Timing and Delinquency: Gender as a Moderator

Because the quadratic term was not found to be significant, the linear model was carried into the multiple group analyses to test gender as a moderator. The full model described above was run simultaneously for males and females. Only partial invariance of the latent factors was achieved2, therefore those variant factor loadings were freely estimated across gender as suggested by Byrne and colleagues (1989).

The unrestricted model showed adequate fit to both groups (χ2 = 220.64 (118), RMSEA = .04, CFI=.96). Partial invariance was achieved and thus the model restricting the invariant measurement weights did not differ significantly from the unrestricted model (Δχ2 = 5.00 (5), ns). The χ2 difference when the structural weights were restricted was not significant (Δχ2 = 3.08 (3), ns ) indicating there were no interaction effects. Parameter estimates for both groups can be found in Table 3.

Pubertal Timing and Delinquency: Maltreatment as a Moderator

For the full model between maltreatment and comparison groups the unconstrained model fit both groups adequately (χ2 = 223.81 (118), RMSEA = .04, CFI=.96). The model requiring partial invariance of the measurement weights was not significantly different from the unrestricted model (Δχ2 = 5.79 (4), ns). Lastly, when the structural weights were restricted the χ2 difference was not significantly different from the measurement model (Δχ2 = 4.22 (3), ns) indicating that the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency was not moderated by maltreatment status for either the cross-sectional or longitudinal relationships. All parameter estimates can be found in Table 3.

Pubertal Timing and Delinquency: Testing a Three-Way Interaction

A three way interaction between pubertal timing, maltreatment, and gender was tested via multiple group analyses. There were no significant interaction effects for the multiple group analyses between the maltreated males and comparison males, maltreated males and comparison females, or comparison males and maltreated females.

For the maltreated females versus comparison females there was not a significant difference between the unrestricted and measurement weights restricted model (Δχ2 = 6.06 (5), ns), however the difference between the measurement model and structural weights restricted model was marginally significant (Δχ2 = 6.55 (3), p=.09). The model fit improved significantly when the restriction on the parameter from Time 2 pubertal timing to Time 2 delinquency was released (Δχ2 = 4.09 (1), p=.04). The parameter estimate was significantly higher for the comparison group although the coefficient was only marginally significant for the comparison group and not significant for the maltreated group (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Parameter estimates from multiple group models testing both gender and maltreatment as moderators

| Full Model | Unstandardized parameter estimates (SE) | Standardized parameter estimates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Maltreated | Comparison | Maltreated | Comparison | Maltreated | Comparison | Maltreated | Comparison | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| T1pubertal timing→T1delinquency | .58 (.39) | .52 (.20) | .32 (.20) | −.67 (.66) | .14 | .35**a | .16† | −.15b |

| T1pubertal timing→T2delinquency | −.34 (.27) | −.02 (.21) | −.30 (1.72) | −1.17 (.77) | −.14 | −.02 | −.21 | −.58 |

| T2pubertal timing→T2delinquency | .35 (.24) | .34 (.16) | .46 (1.52) | 2.43 (1.33) | .15a | .28* | .38a | .85†b |

Note: all parameter estimates are from unconstrained model;

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.10; coefficients with different superscripts are significantly different at p<.09

For the comparison males versus comparison females there was no significant difference between the unrestricted and measurement weights restricted model (Δχ2 = 9.28 (7), ns), however the difference between the measurement model and structural weights restricted model was significant (Δχ2 = 9.05 (3), p=.03). The model fit improved significantly when the restriction on the parameter from Time 1 pubertal timing to Time 1 delinquency was lifted (Δχ2 = 3.09 (1), p=.08). The parameter estimate was negative for comparison females and positive for comparison males although the coefficient was only significant for comparison males (see Table 4 for parameter estimates).

For the maltreated males versus comparison females there was no significant difference between the unrestricted and measurement weights restricted model (Δχ2 = 10.20 (6), ns), however the difference between the measurement model and structural weights restricted model was marginally significant (Δχ2 = 7.35 (3), p=.06). The model fit improved when the restriction on the parameter from Time 2 pubertal timing to Time 2 delinquency was released (Δχ2 = 3.48 (1), p=.06). The parameter estimate was significantly higher for comparison females although the coefficient was only marginally significant (see Table 4 for parameter estimates).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between self-reported pubertal timing and delinquent behavior in a sample of maltreated and comparison adolescents. Of primary interest was the main effect of pubertal timing on delinquency as well as moderation of this effect by gender and maltreatment status. In agreement with much of the literature (Caspi et al., 1993; Cota-Robles et al., 2002; Haynie, 2003; Williams & Dunlop, 1999), the present study found a linear relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency; earlier pubertal timing was related to higher delinquency. In addition, this association was not found to be significantly different for males or females implying that for both genders early pubertal timing was related to higher delinquency. Although these results replicate previous findings, they extend them in several important ways. First, the bulk of pubertal research has been conducted with samples of middle-class white adolescents whereas the present study used a sample primarily composed of African American and Hispanic adolescents from an urban area. Additionally, this sample included an equal composition of males and females which allowed satisfactory examination of gender differences. This study is unique in the use of multiple indicators of pubertal development to construct a latent variable to measure pubertal timing and in the use of multiple-group structural equation modeling to examine interaction effects. Furthermore, this is one of the first studies to examine maltreatment status as a moderator of the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency.

These results support the early timing hypothesis by showing a linear relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency cross-sectionally at Time 1 and Time 2. However, when the effect of Time 1 delinquency was controlled for, the relationship between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency was not significant. This result may imply only short term effects of early pubertal timing. Alternatively, the finding may be due to discontinuity of pubertal timing or delinquency. The changes in delinquent behavior across one year may be more due to age or peer effects than to pubertal development at an earlier time. Caspi et al. (1993) found no effects of age at menarche on delinquent behavior at age 15 although there was an effect on norm-violating behavior at age 13. The stronger cross-sectional associations found here and in other studies (Cota-Robles et al., 2002; Williams & Dunlop, 1999) may indicate pubertal stage or pubertal tempo effects that were not taken into account. That is, early maturers at Time 1 may not all still be early in their pubertal maturation at Time 2, or being an early maturer may be more salient at the younger ages. Overall, consistent with previous research and the expectations set forth in this study, earlier pubertal timing seems to be a risk factor for delinquent behavior for both males and females (Caspi et al., 1993; Ge et al., 2002; Graber et al., 1997; Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2003). The present findings add support to this literature as well as extending the results to urban populations.

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine maltreatment as a moderator of pubertal timing and delinquency. Contrary to expectations, the results from multiple group models between maltreatment and comparison groups showed that maltreatment did not moderate the relationship between pubertal timing and delinquency for the total sample. Similar to the gender analyses, this result demonstrates that earlier pubertal timing is related to higher delinquency for both maltreated and comparison adolescents. To further tease apart the interaction between pubertal timing, gender, and maltreatment experience, multiple group models were used to test for differences between maltreated males, maltreated females, comparison males, and comparison females. The results of these analyses showed that the relationship between Time 1 pubertal timing and Time 1 delinquency was significantly different for comparison males and females. This association was positive and significant in the comparison males but negative and not significant in the comparison females. The relationship between Time 2 pubertal timing and Time 2 delinquency was significantly different between maltreated and comparison females (the coefficient was higher and marginally significant in the comparison females and nonsignificant in the maltreated females) and between maltreated males and comparison females (the coefficient was higher and marginally significant in the comparison females and nonsignificant in the maltreated males). A cautionary note should be added because some of the interaction effects only approached significance and should be interpreted as such.

There are several limitations of the current study that should be taken into account. One limitation is the dichotomization of maltreatment experience. Although many studies find group differences when simply categorizing maltreatment versus non-maltreatment groups (Hill, 2006; Pepin & Banyard, 2006), there are complexities in specific characteristics of maltreatment that may affect the relationships examined in this study. Although the relationship between child maltreatment and delinquency has been demonstrated for all types of abuse and neglect, physical abuse in particular has been linked to aggressive and violent behavior (S. Brown, 1984; Weatherburn & Lind, 1998). Additionally, in a retrospective study, sexual abuse was related to earlier onset of menstruation in females (J. Brown, Cohen, Chen, Smailes, & Johnson, 2004). Therefore, specific types of abuse may be more or less associated with either pubertal development or delinquency. Additionally there are other characteristics of early environments that have been found to affect the timing of pubertal maturation. According to Ellis (2004) family adversity is related to early pubertal development, however empirical support only exists for females (Tither & Ellis, 2008). Maltreating families may have some of the family characteristics that are linked to early pubertal onset which demonstrates the complexity of understanding these associations.

A second limitation of this study is the young end of the age range of the sample. Although the adolescents ranged from 9 to 13 years at the first assessment, there is the possibility that some of the 9 year olds had not yet entered puberty which then makes it difficult to measure. However, the strategy for constructing the pubertal timing variable allowed for the use of those who had not yet begun puberty by comparing them to others of the same age and gender. If all the 9 year olds had not begun puberty then they would all be calculated as on-time in their development. Because the pubertal timing variable was created as a measure relative to peers and not relative to the national norms, it was a better reflection of how they may appear in reference to their peer group. This is an important point because one proposed mechanism linking early pubertal development to delinquency is through the interaction of early maturers with older peers (Caspi et al., 1993; Haynie, 2003). Those appearing more physically mature within their peer group may receive attention from older peers who model and draw them into delinquent behavior.

A third limitation is that both the measures of pubertal development and delinquency were obtained by self-report. Although self-reports of pubertal development have been found comparable to physician-reports, pubertal ratings from multiple informants would strengthen the validity of these measures. However, the use of multiple informants, in particular physician examination, is not always a feasible option. Multiple informants would add to the measurement of delinquency as well, although using police reports or arrest records would discount a majority of adolescents as many have not been involved in the juvenile justice system. Perhaps for the assessment of more serious delinquency, official reports would be most useful. Even within the present study the frequency of delinquent behavior was quite low. This may be in part due to the young age range of the sample. The pattern of correlations between puberty and delinquency variables at Time 1 differed from Time 2 indicating that there may be a shift in the types of delinquent behaviors as an adolescent gets older. Additionally, delinquency may be more evident in older adolescents therefore it would be informative to follow the adolescents beyond the time points and ages of the present study.

Lastly, this study is limited in the examination of other contextual factors or mediational processes. Although gender and maltreatment experience were examined as moderators, there may be other factors related to parenting, peers, or neighborhoods that affect these relationships. Evidence suggests that for males, the association between pubertal stage and delinquency is moderated by negative interactional skills, poor impulse control, and having antisocial peers. (Beaver & Wright, 2005). In addition, the present results do not address mechanisms by which these associations may function. For example, there is evidence that suggests a strong influence of peers on the behavior of early maturers (Caspi & Moffitt, 1991; Haynie, 2003; Lynne et al., 2007).

Future research should continue to examine moderators of the relationship between pubertal development and various maladaptive outcomes. In addition, effort should be placed in identifying the mechanisms by which pubertal development affects behavioral and mental health functioning. Maltreatment experience should be examined more closely in regards to the characteristics of the abuse; frequency, chronicity, duration, multiple types, multiple perpetrators, etc. Identifying those characteristics most highly associated with problematic outcomes will allow future studies to target those individuals at risk in an effort to reduce those difficulties. The present findings support the use of multiple indicators of pubertal development and should be considered in future research as this method may give a more complete and accurate description of the pubertal process. Longitudinal studies will greatly enhance our understanding of the developmental trajectories associated with pubertal development. By following children from before the onset of puberty through adolescence and into early adulthood, the short and long-term impact of pubertal development can be assessed. In addition, there may be different associations between pubertal development and various outcomes based on the age and developmental period. Some outcomes may be more salient and critical to address early in adolescence, whereas other outcomes may be more pertinent in later adolescence. There may be certain outcomes which tend to be more transient or moderators which may enhance the persistence of problem behaviors. Knowledge of such risk factors can inform interventions aimed at reducing the deleterious effects associated with off-time pubertal development.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from a National Institutes of Health R01 grant HD39129, Penelope K. Trickett P.I.

Footnotes

For results of the analyses with the quadratic term contact the first author

For the complete results of measurement invariance analyses contact the first author

References

- Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–87. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 5.0. Chicago: Smallwaters; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bal S, Crombez G, Van Oost P, Debourdeaudhuij I. The role of social support in well-being and coping with self-reported stressful events in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(12):1377–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM, Wright JP. Biosocial development and delinquency involvement. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2005;3(2):168–192. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton FG, Reich JW, Gutierres SE. Delinquency patterns in maltreated children. Victimology. 1977;2:349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Cohen P, Chen H, Smailes E, Johnson JG. Sexual trajectories of abused and neglected youths. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2004;25(2):77–82. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. Social class, child maltreatment, and delinquent behavior. Criminology. 1984;22:259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM, Shavelson RJ, Muthen B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105(3):456–466. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Lynam D, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Unraveling girls’ delinquency: biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(1):19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt T. Individual differences are accentuated during periods of social change: the sample case of girls at puberty. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(1):157–168. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Ey S, Grant KE. Taxonomy, assessment, and diagnosis of depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(2):323–344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota-Robles S, Neiss M, Rowe DC. The role of puberty in violent and nonviolent delinquency among Anglo American, Mexican American, and African American boys. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2002;17(4):364–376. [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Putnam FW. The psychology of childhood maltreatment. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;3(4):663–678. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood estimation from incomplete data via the EM algorithm (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Rose RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J. Measuring puberty and understanding its impact: a longitudinal study of adolescent twins. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30(4):385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Nottelmann ED, Inoff-Germain G, Chrousos GP. Perceptions of puberty: adolescent, parent, and health care personnel. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:322–329. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Ponirakis A. Pubertal timing and adolescent adjustment and behavior: conclusions vary by rater. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;32(3):157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of Pubertal Maturation in Girls: An Integrated Life History Approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felson RB, Haynie DL. Pubertal development, social factors, and delinquency among adolescent boys. Criminology. 2002;40(4):967–988. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DJ, Rowe DC, Gulley BL. Impact of pubertal status, timing, and age on adolescent sexual experience and delinquency. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1993;8(1):21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, McBride-Murray V. Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(1):42–54. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, McBride-Murray V. Pubertal maturation and African American children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(4):531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Brooks-Gunn J. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(12):1768–1776. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J, Gunnar MR, Cicchetti D. Salivary cortisol in maltreated children: Evidence of relations between neuroendocrine activity and social competence. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7(1):11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL. Context’s of risk? Explaining the link between girls’ pubertal development and their delinquent involvement. Social Forces. 2003;82(1):355–397. [Google Scholar]

- Hill J. Child maltreatment and depression in adults: Implications for prevention. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation. 2006;3(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M, Rantanen P, Rimpela M. Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitenberg H, Gibson LE, Novy PL. Individual differences among undergraduate women in methods of coping with stressful events: The impact of cumulative childhood stressors and abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynne SD, Graber JA, Nichols TR, Brooks-Gunn J, Botvin GJ. Links between pubertal timing, peer influences, and externalizing behaviors among urban students followed through middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:181.e187–181.e113. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurnett K, Lahey BB, Rathouz PJ, Loeber R. Low salivary cortisol and persistent aggression in boys referred for disruptive behavior. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57(1):38–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord J. A forty year perspective on child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1983;7:265–270. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(83)90003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris NM, Udry RJ. Validation of a self-administered instrument to assess stage of adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1980;9(3):271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF02088471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Kaplan D, Hollis M. On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika. 1987;52:431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Obeidallah D, Brennan RT, Brooks-Gunn J, Earls F. Links between pubertal timing and neighborhood contexts: implications for girls’ violent behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(12):1460–1468. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000142667.52062.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard T, Woodbury MA. Proceedings of the 6th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1972. A missing information principle: Theory and applications. [Google Scholar]

- Pepin EN, Banyard VL. Social support: A mediator between child maltreatment and developmental outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(4):617–630. [Google Scholar]

- Peskin H. Influence of the developmental schedule of puberty on learning and ego functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1973;2(4):273–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02213700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett LJ, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Taylor B. The biological approach to adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. New York: Wiley; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ping RA., Jr Latent variable interaction and quadratic effect estimation: A two-step technique using structural equation analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Popma A, Jansen LMC, Vermeiren R, Steiner H, Raine A, Van Goozen SHM, et al. Hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis and autonomic activity during stress in delinquent male adolescents and controls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(8):948–957. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Age changes in depressive disorders: Some developmental considerations. In: Rutter M, Izard CE, Read PB, editors. Depression in young people: Developmental and clinical perspectives. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (Version 2.0) 1999 http://www.stat.psu.edu/~jls/misoftwa.html.

- Simmons RG, Burgeson R, Carlton-Ford S, Blythe DA. The impact of cumulative change in early adolescence. Child Development. 1987;58(5):1220–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarullo AR, Gunnar MR. Child maltreatment and the developing HPA axis. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50(4):632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tither JM, Ellis BJ. Impact of fathers on daughters’ age at menarche: A genetically and environmentally controlled sibling study. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(5):1409–1420. doi: 10.1037/a0013065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherburn D, Lind B. Poverty, parenting, peers, and crime-prone neighborhoods. Australian Institute of Criminology; Canberra, ACT, Australia: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. Does violence beget violence? A critical examination of the literature. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106(1):3–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Dunlop LC. Pubertal timing and self-reported delinquency among male adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22:157–171. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff MT, Leiter J, Myers KA, Johnson MC. Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology. 1993;31:173–202. [Google Scholar]