Abstract

Objectives

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) was recently reported as a major diarrheagenic pathogen in infant and adult travelers, both in developing and developed countries. EAEC strains are known to be highly resistant to antibiotics including quinolones. Therefore in this study we have determined the various mechanisms of quinolone resistance in EAEC strains isolated in Korea.

Methods

For 26 EAEC strains highly resistant to fluoroquinolone, minimal inhibitory concentrations for fluoroquinolones were determined, mutations in the quinolone target genes were identified by PCR and sequencing, the presence of transferable quinolone resistance mechanism were identified by PCR, and the contribution of the efflux pump was determined by synergy tests using a proton pump inhibitor. The expression levels of efflux pump-related genes were identified by relative quantification using real-time PCR.

Results

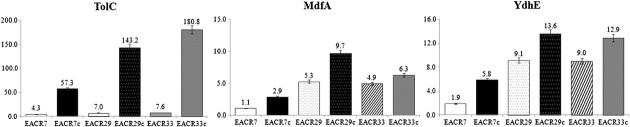

Apart from two, all tested isolates had common mutations on GyrA (Ser83Leu and Ser87Gly) and ParC (Ser80Gln). Isolates EACR24 and EACR39 had mutations that have not been reported previously: Ala81Pro in ParC and Arg157Gly in GyrA, respectively. Increased susceptibility of all the tested isolates to ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin in the presence of the pump inhibitor implies that efflux pumps contributed to the resistance against fluoroquinolones. Expression of the efflux pump-related genes, tolC, mdfA, and ydhE, were induced in isolates EACR 07, EACR 29, and EACR 33 in the presence of ciprofloxacin.

Conclusion

These results indicate that quinolone resistance of EAEC strains mainly results from the combination of mutations in the target enzyme and an increased expression of efflux pump-related genes. The mutations Ala81Pro in ParC and Arg157Gly in GyrA have not been reported previously the exact influence of these mutations should be investigated further.

Keywords: aac(6')-Ib-cr, efflux pump, enteroaggregative Escherichia coli, fluoroquinolone, gyrA, parC, qnr

1. Introduction

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) is one of the diarrheagenic E. coli strains, and its importance in public health is increasing around the world [1]. EAEC has been implicated as major etiologic pathogens of infant gastroenteritis in developing countries, and associated with persistent diarrhea longer than 14 days, which is related to high mortality in these regions [2,3]. It was recently also reported to be one of the major diarrheagenic pathogens in young children and adults traveling in developed countries [4].

EAEC is defined by "stacked-brick" type aggregative adherence to HEp-2 cells. The pathogenesis of EAEC infection is not fully understood but it is presumed to result from the characteristic that it adheres to the intestinal mucosa using adherence fimbriae, and causes damage to the mucosal epithelium [2,5,6]. The putative virulence factors are mostly in the 60–65 MDa aggregative adherence plasmids [1,7].

The ratio of antibiotic resistant strains in EAEC is higher than in other diarrheagenic E. coli strains. In Peru, the antibiotic resistance ratio of diffuse adhering E. coli and EAEC was higher than that of other E. coli strains, and, in Iran, the EAEC isolates showed 100% resistance to ampicillin, and 64.3%, 57.1%, and 42.9% to tetracyclin, nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin (CIP), respectively [8,9].

Generally, EAEC strains are highly resistant to ampicillin, nalidixic acid, cotrimoxazol, and others. It is presumed that persistent diarrhea increases the chance of EAEC being exposed to the various antibiotics caused the highly antibiotic resistant nature of EAEC [9].

Quinolone resistance in enteric bacteria is mainly a result of mutations in the target genes of quinolone encoding DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV [10], and by the active efflux of quinolone. These resistance mechanisms cannot be transmitted to other bacteria, but recently a transferable quinolone resistance mechanism, qnr, has been reported [11]. It has also been reported that quinolone resistance often results from the combination of target alteration and active efflux pumps in enteric bacteria [12-14]. In a previous study, we reported that the efflux system including MdfA is involved in quinolone resistance in Shigella flexneri [15]. The contribution of the efflux system to quinolone resistance in E. coli isolated in the USA has been also reported [3].

In this study, we have determined the mechanism of quinolone resistance resulting from the presence of target alteration, efflux pump, and other transferrable mechanisms in EAEC strains isolated in Korea.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial isolates

We received 227 clinical EAEC isolates from the national public health network of Korea in 2008–2009. The antibiotic susceptibility of these isolates was performed by the disk diffusion test, according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [16]. We selected 26 EAEC isolates showing high resistance to CIP (inhibitory zone was <6 mm).

2.2. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of CIP and norfloxacin (NOR) were determined by E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality assurance strain [16,17]. CLSI criteria were used to categorize strains as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant [16].

2.3. DNA sequence analysis of the quinolone resistance-determining regions

The quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes were amplified by PCR [15] and sequenced using an ABI 3700 sequencer (Applied Biosystem, Foster, CA, USA). These portions of the QRDRs corresponded to amino acid residues 54–171 of GyrA, 397–520 of GyrB, 12–130 of ParC, and 421–524 of ParE.

2.4. Amplification of qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac(6’)-Ib-cr genes

Protocols for the amplification of qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac(6’)-Ib-cr genes have been previously described [15]. The PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 μL containing 2 ìL of template DNA, 1× reaction buffer, 0.2mM of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 20 pM of each primer, and 3.5 units of Taq polymerase. The assays were performed in a Peltier Thermal Cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, MA, USA) under the following conditions: one cycle of 94 ℃ for 5 minutes followed by 30 cycles of 94 ℃ for 1 minute, 60 ℃ for 1 minute, and 72 ℃ for 1 minute and a final extension of 72 ℃ for 5 minutes.

2.5. Synergy tests

Synergy experiments were performed using the fluoroquinolones CIP and NOR, and the efflux pump inhibitor, reserpine. Reserpine was added in Muller- Hinton agar at the concentration of 100s added in Muller-Hin testing to CIP and NOR by E-test was performed in agar plates with or without reserpine [17,18].

2.6. Expression of mdfA, tolC, and ydhE

The expression of each gene was investigated using real-time PCR as described previously [15]. The cycling conditions were 40 cycles of 95 ℃ for 15 seconds followed by 60 ℃ for 1 minute. Quantification was based on the threshold cycle value, which was determined with the aid of the SDS 2.1 software system (Applied Biosystems). Relative gene expression level was calculated using threshold cycle (CT) as 2–ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT = ΔCT (sample) – ΔCT (control), and ΔCT is the CT of the target gene subtracted from the CT of the housekeeping gene [19]. All tests were repeated five times and the relative gene expression value is indicated average of five tests. Relative gene expression level of efflux pump related genes were compared with those of the quinolone susceptible strain E. coli ATCC 25922.

3. Results

3.1. Susceptibility of Shigella isolates to fluoroquinolones

All of the 26 EAEC isolates were found to be highly resistant to the fluoroquinolones tested: CIP (MIC, 32–256 μg/mL), and NOR (MIC ranges of 32–256 μg/mL).

3.2. Mutations in the genes gyrA and parC

From the sequence analysis of fluoroquinolone resistance-related genes, there were no alterations of amino acid sequence in GyrB and ParE, while several mutations were detected in the GyrA and ParC (Table 1). Seventeen isolates among the tested fluoroquinolone resistance isolates had multiple mutations in GyrA (Ser83Leu and Ser87Gly) and ParC (Ser80Gln and Glu84Val or Gly). Seven isolates were observed to have double mutations in GyrA (Ser83Leu and Ser87Leu) and one in ParC (Ser80Gln). The combination of GyrA gene (Ser83 and/or Asp87) and ParC gene (Ser80 and/or Glu84) were frequently found in fluoroquinolone highly resistant isolates. However, fluoroquinolone resistant isolates EACR 24 and 39 were found to have novel mutations in ParC and GyrA, respectively. EACR 24 contained two substitutions, one in GyrA (Ser83Leu) and one in ParC (Ala81Pro; GenBank No. EU512995). EACR 39 exhibited four substitutions, three in GyrA (Ser83Leu, Asp87Gly, Arg157Gly; GenBank No. HM753589) and ParC (Ser80Gln). The mutations Arg157Gly in GyrA and Ala81Pro in ParC have not been reported previously. There was no notable difference in MIC for CIP and NOR between the triple and quadruple mutants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of EAEC isolates with resistance to fluoroquinolones

| MIC (μg/mL) | gyrA amino acid at codon | parC amino acid at codon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 83 | 87 | 157 | 80 | 81 | 84 | ||||||

| Strain no. | CIP | CIP + Reserpine | Nor | Nor + Reserpine | GAC (Asp) | GAC (Asp) | CGT (Arg) | AGC (Ser) | GCC (Ala) | GAA (Glu) | qnr, aac(6’)Ib-cr, qepA type |

| EACR01 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR02 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR03 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR04 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR05 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR06 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR07 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | |

| EACR09 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR10 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR11 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR12 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR15 | 32 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | |

| EACR17 | 32 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR18 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR21 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR22 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR23 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -T-(Val) | |

| EACR24 | 32 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | – | – | – | C–(Pro) | – | |

| EACR25 | 128 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | aac(6’) Ib-cr |

| EACR29 | 256 | <2 | 64 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | aac(6’) Ib-cr |

| EACR31 | 256 | <2 | 64 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | |

| EACR32 | 128 | <2 | 64 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | aac(6’) Ib-cr |

| EACR33 | <256 | <2 | 256 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -G-(Gly) | qnrA |

| EACR38 | 128 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | – | |

| EACR39 | 128 | <2 | 64 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | G-(Gly) | -AG(Gln) | – | – | |

| EACR41 | 64 | <2 | 32 | <2 | -T-(Leu) | -G-(Gly) | – | -AG(Gln) | – | -G-(Gly) | |

Each value is the average of five replicates.

CIP = ciprofloxacin; NOR =norfloxacin.

3.3. Presence of qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac(6’)-Ib-cr genes

Among the 26 fluoroquinolone resistant isolates, qnrA was only detected in EACR 33. Three isolates (EACR 25, 29, and 32) were PCR positive for aac(6’)-Ib-cr. However, qnrB and qnrS were not identified in any of the tested fluoroquinolone resistant isolates.

3.4. Involvement of putative efflux pumps for fluoroquinolone resistance

To elucidate the involvement of the efflux pump in floroquinolone resistance in EAEC isolates, synergy experiments were performed using the efflux pump inhibitor, reserpine and the fluoroquinolones CIP and NOR. The MICs for 26 isolates of fluoroquinolones were decreased 32- to 256-fold in agar plate containing reserpine in comparison with those observed in reserpine-free medium (Table 1).

3.5. Expression of genes, mdfA, tolC, and ydhE, encoding efflux pump

EACR07, EACR29, and EACR33 were selected to investigate the extent of intervention of efflux pump in fluoroquinolone resistance, because EACR07 and EACR29 showed different MIC for fluoroquinolones but had same mutation profile on quinolone target enzyme, and EACR29 and EACR31 showed a similar MIC but have different mutation profiles. Real-time PCR showed that isolates EACR07, EACR29, and EACR33 exhibited approximately 9 times higher expression of tolC, mdhA, and ydhE, respectively, than the E. coli ATCC 25922 control strain (Figure 1). When CIP was added to medium, the expression of the three genes were greatly increased in all three isolates. The EACR07 isolate expressed 57.33 times more tolC, 2.9 times more mdfA, and 5.8 times more ydhE than the control strain. EACR29 exhibited 143.2 times more tolC, 9.7 times more mdfA, and 13.6 times more ydhE than the control strain. EACR33 exhibited 180.8 times more tolC, 6.3 times more mdfA, and 12.9 times more ydhE than the control strain.

Figure 1. Expression of tolC, mdfA, and ydhE measured by RT-PCR in the absence and presence of ciprofloxacin. Each value is the average of five culture replicates, each of which was evaluated twice. Relative gene expression levels were calculated as 2–ΔΔCT, where ΔΔCT = –ΔCT (sample) –ΔCT (control) [3]. CT = threshold cycle.

4. Discussion

EAEC is a main cause of persistent diarrhea in children in developing regions and a prevalent cause of traveler’s diarrhea. Recently it was reported that EAEC also can cause acute diarrhea in children in both developing and industrialized countries [4]. Because of this, even though the EAEC was most recently categorized as diarrheagenic E. coli, it became an emerging enteric pathogen.

EAEC is also known to have relatively high resistance to β-lactams and quinolones compared with other E. coli because it has repeated exposure to antimicrobial agent or may interact with other resistant flora that cause chronic diarrhea [8].

In this study, 26 EAEC clinical isolates with high resistance to fluoroquinolones were examined to identify their quinolone resistance mechanism. Resistance to quinolones is usually due to mutations of the bacterial targets, DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV [10]. In this study, all tested isolates had multiple mutations on GyrA and ParC at the QRDR of each.

Apart from EACR24 and EACR 39, all tested isolates had the common mutations on GyrA (Ser83Leu and Ser87Gly) and ParC (Ser80Gln). Seventeen isolates had double mutations on both GyrA and ParC, seven isolates had double mutations on GyrA and a single mutation on ParC. In EACR 39, we found a substitution of arginine to glycine at Codon 157 in GyrA, which has not been reported previously. This mutation, however, is presumed to contribute insignificantly to the resistance, because the MIC for fluoroquinolone is similar to that of other resistant strains that have the same mutations apart from Arg157Gly in GyrA. In EACR24, we also found a mutation that has not been reported before: Ala81Pro in ParC. The MIC value for CIP of EARC24 was 32 μg/mL, and it had two mutations in the target genes GyrA and ParC; therefore, this newly reported mutation seems to have a great impact on fluoroquinolone resistance. The exact influence of these two newly reported mutations should be investigated further.

In general, reduced susceptibility due to a change of Ser83 in GyrA leads to an increase in resistance with the addition of one or two mutations in GyrA or ParC [20]. However, there was no comparable difference in MICs for CIP and NOR. For example, EACR07 and EACR29 have the same mutation profile, two in GyrA and one in ParC, but the MIC of CIP was 64 μg/mL for EACR04 and 256 μg/mL for EACR33. Therefore, we can deduce that other resistance mechanisms such as efflux are concerned with these isolates.

Efflux pumps utilize the energy of the proton motive force to transport out the antibiotics out of cells [21]. In all the 26 isolates, the contribution of efflux pump to fluoroquinolone resistance was determined, because increased susceptibility of all the tested isolates to CIP and NOR in the presence of a proton pump inhibitor implied the presence of energy-dependent active efflux pumps for fluoroquinolones. The loss of multidrug efflux could neutralize the resistance contributed by target site alteration as has been shown in E. coli, Shigella, and Salmonella typhimurium [12,14,15].

Expression of tolC for resistance-nodulation-cell division superfamily transporter, mdfA for major facilitator superfamily transporter, and ydhE for multiantimicrobial extrusion protein family transporter was tested in EACR07, EACR29, and EACR 33. There was a clear relationship between increased expression of genes for efflux pumps and resistance to fluoroquinolone in all three isolates. Expression of tolC, mdfA, and ydhE was greatly induced in the presence of ciprofloxacin, but the extent was different from the tested isolates. EACR33 produced the largest amount of tolC in the presence of ciprofloxacin, and it has highest MIC value for fluoroquinolones among the tested isolates. However, the expression level of mdfA and ydhE was less than that of EACR24. This can be explained by previous reports that the fluoroquinolone efflux pump of E. coli is mainly encoded by acrAB and tolC genes [22,23] EACR29 produced 2.3–3.3 times more transporters than EACR07 in the presence of ciprofloxacin. This may explain the difference in MICs between the isolates that have the same mutation profile on the target enzyme. In conclusion, these results indicates that resistance to fluoroquinolones resulted from both the presence of target site mutations and the expression of genes for efflux pumps.

In recent studies, the qnrA, B, S and aac(6’)-Ib-cr genes were shown to be related to quinolone resistance [11]. We detected aac(6’)-Ib-cr genes in EACR29, and in qnrA, EACR33. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine whether the expression of these genes contribute to fluoroquinolone resistance. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the mutations Ala81Pro in ParC and Arg157Gly in GyrA.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a fund (2011-N41005-00) by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Cerna JF, Nataro JP, Estrada-Garcia T. Multiplex PCR for detection of three plasmid-borne genes of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2003 May;41(5):2138–40. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.5.2138-2140.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nataro JP, Deng Y, Maneval DR, et al. Aggregative adherence fimbriae I of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli mediate adherence to HEp-2 cells and hemagglutination of human erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1992 Jun;60(6):2297–304. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2297-2304.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swick MC, Morgan-Linnell SK, Carlson KM, et al. Expression of multidrug efflux pump genes acrAB-tolC, mdfA, and norE in Escherichia coli clinical isolates as a function of fluoroquinolone and multidrug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Feb;55(2):921–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00996-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur P, Chakraborti A, Asea A. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli: an emerging enteric food borne pathogen. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2010;2010:254159. doi: 10.1155/2010/254159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto T, Nakazawa M. Detection and sequences of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains isolated from piglets and calves with diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 1997 Jan;35(1):223–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.223-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudley EG, Abe C, Ghigo JM, et al. An IncI1 plasmid contributes to the adherence of the atypical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain C1096 to cultured cells and abiotic surfaces. Infect Immun. 2006 Apr;74(4):2102–14. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2102-2114.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang ZD, Greenberg D, Nataro JP, et al. Rate of occurrence and pathogenic effect of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence factors in international travelers. J Clin Microbiol. 2002 Nov;40(11):4185–90. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4185-4190.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochoa TJ, Ruiz J, Molina M, et al. High frequency of antimicrobial drug resistance of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in infants in Peru. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Aug;81(2):296–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aslani MM, Alikhani MY, Zavari A, et al. Characterization of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) clinical isolates and their antibiotic resistance pattern. Int J Infect Dis. 2011 Feb;15(2):e136–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997 Sep;61(3):377–92. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robicsek A, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. The worldwide emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006 Oct;6(10):629–40. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70599-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole K. Efflux-mediated multiresistance in gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004 Jan;10(1):12–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oethinger M, Kern WV, Jellen-Ritter AS, et al. Ineffectiveness of topoisomerase mutations in mediating clinically significant fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli in the absence of the AcrAB efflux pump. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000 Jan;44(1):10–3. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.1.10-13.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baucheron S, Imberechts H, Chaslus-Dancla E, et al. The AcrB multidrug transporter plays a major role in high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium phage type DT204. Microb Drug Resist. 2002;8(4):281–9. doi: 10.1089/10766290260469543. Winter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JY, Kim SH, Jeon SM, et al. Resistance to fluoroquinolones by the combination of target site mutations and enhanced expression of genes for efflux pumps in Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei strains isolated in Korea. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008 Aug;14(8):760–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 21st informational supplement M100–S21. CLSI; Wayne, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truong QC, Nguyen Van JC, Shlaes D, et al. A novel, double mutation in DNA gyrase A of Escherichia coli conferring resistance to quinolone antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997 Jan;41(1):85–90. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricci V, Piddock L. Accumulation of garenoxacin by Bacteroides fragilis compared with that of five fluoroquinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 Oct;52(4):605–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giulietti A, Overbergh L, Valckx D,, et al. An overview of realtime quantitative PCR: applications to quantify cytokine gene expression. Methods. 2001 Dec;25(4):386–401. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vila J, Ruiz J, Goñi P, et al. Detection of mutations in parC in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996 Feb;40(2):491–3. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pao SS, Paulsen IT, Saier Jr MH. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998 Mar;62(1):1–34. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.1-34.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fralick JA. Evidence that TolC is required for functioning of the Mar/AcrAB efflux pump of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996 Oct;178(19):5803–5. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5803-5805.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma D, Cook DN, Hearst JE, et al. Efflux pumps and drug resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1994 Dec;2(12):489–93. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90654-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]