Abstract

Background and Aims

In recent years considerable effort has focused on linking wood anatomy and key ecological traits. Studies analysing large databases have described how these ecological traits vary as a function of wood anatomical traits related to conduction and support, but have not considered how these functions interact with cells involved in storage of water and carbohydrates (i.e. parenchyma cells).

Methods

We analyzed, in a phylogenetic context, the functional relationship between cell types performing each of the three xylem functions (conduction, support and storage) and wood density and theoretical conductivity using a sample of approx. 800 tree species from China.

Key Results

Axial parenchyma and rays had distinct evolutionary correlation patterns. An evolutionary link was found between high conduction capacity and larger amounts of axial parenchyma that is probably related to water storage capacity and embolism repair, while larger amounts of ray tissue have evolved with increased mechanical support and reduced hydraulic capacity. In a phylogenetic principal component analysis this association of axial parenchyma with increased conduction capacity and rays with wood density represented orthogonal axes of variation. In multivariate space, however, the proportion of rays might be positively associated with conductance and negatively with wood density, indicating flexibility in these axes in species with wide rays.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that parenchyma types may differ in function. The functional axes represented by different cell types were conserved across lineages, suggesting a significant role in the ecological strategies of the angiosperms.

Keywords: Ecological strategies, evolutionary conservatism, hydraulic conductivity, parenchyma, water storage, wood anatomy, wood density

INTRODUCTION

Wood performs three critical functions: mechanical support of the photosynthetic surface (Rowe and Speck, 2005); storage of water, sugar and other nutrients (e.g. Kozlowski, 1992; Sauter and van Cleve, 1994); and conduction of water and other substances from the soil to the photosynthetic surface (e.g. Sperry, 2003). In angiosperms, each of these functions is generally carried out by particular cells types so that mechanical support is primarily determined by fibres, storage by living cells such as parenchyma, and water conduction by xylem vessels. One cell type can, however, perform more than one function. For example, living fibres can be the storage compartment in woods with scanty parenchyma (Spackman and Swamy, 1949; Carlquist, 2001; Wheeler et al., 2007) and also function as support cells (Govindarajaru and Swamy, 1955). Because wood carries out all these different tasks simultaneously, environmental demands that require a prominent role for a particular function can create a trade-off and/or positive interaction with other functional axes of variation. For example, increased mechanical support often decreases water conduction efficiency but increases resistance to cavitation (e.g. Hacke et al., 2001; Jacobsen et al., 2005). These inter-relationships between hydraulic and mechanical properties are, however, a matter of an ongoing debate (Awad et al., 2012) since trade-offs may (e.g. Gartner, 1991) or may not be recognized (e.g. Woodrum et al., 2003; Pratt et al., 2007). Although defence and decay resistance through compartmentalization of infection is a fourth critical wood function, we did not include it in our analysis since it is unclear how the anatomical traits we analysed here contribute to this particular ecological axis.

Wood density is a key functional trait that has been the focus of extensive research in the last few years. Since wood density describes the amount of carbon invested in support (King et al., 2005, 2006), it is related to a variety of ecological dimensions linked to life history traits (e.g. growth rate, survival or life span). For instance, wood density is inversely related to growth rates (e.g. Enquist et al., 1999; Roderick, 2000; Muller-Landau, 2004) and successional position (e.g. Swaine and Whitmore, 1988). Species with low wood density tend to be comparatively short-lived, fast-growing pioneers, while species with high wood density tend to be long-lived climax species (Saldarriaga et al., 1988; Swaine and Whitmore, 1988; Wiemann and Williamson, 1988, 1989). High disturbance and turnover rates favour fast-growing species with low wood density (ter Steege and Hammond, 2001).

Increased wood density positively influences cavitation resistance (e.g. Pratt et al., 2007) by increasing the strength of fibres associated with vessels (Jacobsen et al., 2005). However, increased hydraulic conductance, mainly driven by transpiration needs, may negatively affect mechanical stability of wood (e.g. Gartner, 1991). Zanne et al. (2010) and Zanne and Falster (2010) described several ways in which adjustments in hydraulic supply may alter wood structure, two of them involving adjustment in vessel characteristics: vessel lumen fraction (i.e. cross-sectional area occupied by open vessel spaces) and vessel composition (i.e. size distribution). However, a relationship between vessel characteristics and wood density cannot be assumed to be universal because while some studies have shown a trade-off between wood density and vessel area (Jacobsen et al., 2005, 2007; Preston et al., 2006) or vessel fraction (Preston et al., 2006), others have shown a lack of association between these variables (Martínez-Cabrera et al., 2009, 2011; Zanne et al., 2010).

Most of the studies dealing with the anatomical determinants of wood density, especially those including large samples from global databases, lack information on the third functional dimension, storage. As axial and radial parenchyma are associated with stem water and nutrient storage, we expect a trade-off between mechanical strength and storage because increased area of parenchyma in stems should be achieved at the expense of other cell types (i.e. fibres), especially if conductance is to be maintained. This trade-off between mechanical properties and amount of parenchyma has been empirically shown in some studies. Jacobsen et al. (2007), for example, found that wood density and the modulus of elasticity (MOE) were inversely related to total parenchyma area. Total parenchyma area and wood density, however, were independent in a study including 61 shrub species across precipitation gradients (Martínez-Cabrera et al., 2009). Martínez-Cabrera et al. (2009) also showed that axial and radial parenchyma have opposite correlation patterns with wood density and several climate variables, suggesting that parenchyma types may have different functional roles. Essentially species with low wood density from wet sites have a high proportion of rays and less axial parenchyma than species from drier areas. This pattern was hypothesized to result from prevention of radial water transport from other regions of the stem during the embolism repair process that could lead to further water loss under high water stress. Other studies have found the opposite pattern of a positive relationship between ray area and wood density (Taylor, 1969; Woodrum et al., 2003; Rahman et al., 2005). Besides the interaction with mechanical properties, both types of xylem parenchyma are important for water transport since they may serve as water reservoirs to prevent embolism formation and provide the osmotic agents (Braun, 1984) to aid embolism repair (e.g. Canny, 1997; Améglio et al., 2002; Bucci et al., 2003). In addition, in some lineages (e.g. Rhamnaceae; Pratt, 2007), higher total amounts of parenchyma are associated with less negative cavitation resistance values (Ψ50 values; water potential at which there is 50 % loss in hydraulic conductivity), indicating that higher xylem vulnerability is associated with increasing parenchyma. In summary, this information indicates that storage capacity, in this case represented by xylem parenchyma, interacts with mechanical and conduction properties, to form co-ordinated units that are modulated to meet particular environmental demands.

Here we compiled a large database of approx. 800 tree species from China to analyse patterns of correlated evolution between proportions of different tissue types and functional characteristics of the stem related to support (wood density), water conduction (potential conductivity, vessel composition and fraction) and storage. While other analyses at global scales have focused on vessel traits to explain variation in wood density and theoretical conductivity, we also question whether there is a clear trade-off among anatomical traits that hypothetically represent mechanical, conduction and storage functions, and how early these axes were established in the history of the lineages. We acknowledge that there is intraspecies (e.g. Gartner et al., 1997) and intra-tree (Lei et al., 1996) radial variation in wood traits associated with ontogenetic changes that might affect the strength of trade-offs mentioned above. Wood density, for example, reflects differences in ecological properties of species [e.g. successional position (Woodcock and Shier, 2002); shade tolerance (Nock et al., 2009)], but there is also radial variation that is linked to ontogenetic variation (Nock et al., 2009). Our target in this study, however, is to determine whether such trade-offs are generally recognized across angiosperm lineages at the species level. We were particularly interested in incorporating axial and radial parenchyma in the study, since these anatomical elements have not been analysed at this large scale before.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of the data set

We compiled wood trait data from nearly 800 Chinese tree species (Yang and Lu, 1993; Yang and Yang, 2001; Yang et al., 2009). Most tree samples were taken from the Eastern Monsoonal climate zone in China where the temperate, sub-tropical and tropical natural forests are distributed (Zhao, 1995). Wood densities from >400 species were collected from various sources (Cheng et al., 1992; Yang et al., 1992; Yang and Lu, 1993; Yang and Yang, 2001, Yang et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2010), but in all cases density was measured using air-dried samples with 15 % water content and following the Chinese national standard (GB 1933-1991, method for determination of the density of wood, 1991). The anatomical data we used were mainly collected from publications by The Chinese Academy of Forestry, which hosts the largest wood collection in China (Yang and Lu, 1993; Yang and Yang, 2001; Yang et al., 2009) and thus the wood anatomical traits were measured following their methods (Zeng et al., 1985). In brief, most angiosperm tree species were sampled from mature trees with a diameter at breast height (DBH) >20 cm in natural forests. The sampled discs were collected at a height of 1·3 m. These discs were cut, from pith to bark, into six equal parts according to the equidistance method, and the anatomical samples were taken from the middle of the outermost part (the closest to the bark). The entire span of one growth ring was thin sectioned. Wood anatomical traits were measured using an optical microscope and an attached image analyser (Q570) (Zeng et al., 1985). The anatomical variables measured were vessel diameter and density, and proportion of cross-sectional area occupied by vessels, fibres, rays, axial parenchyma and cell wall. For vessel diameter and vessel density, 100 vessels were measured in earlywood and latewood of each sample. To measure tissue proportions in cross-section, images were taken using the Q570 image analyser. The percentage area of each cell type, however, was manually determined (Yang and Yang, 2001). Percentage areas of different cell types were determined in fields of view of 1 mm2. In ring-porous woods, the proportion of area occupied by each cell type was determined by measuring four fields of view, two each in earlywood and latewood. In diffuse-porous woods, the proportional area of each cell type was calculated from three fields of view in the beginning, middle and late growth portions of the growth rings. The proportions analysed are thus the mean values of these fields of view. Total cell wall area was the total dark area in a field of view and represents the cell wall of all cell types. Using image analysis to measure total cell wall area in transverse sections is problematic because unstained fibre layers (e.g. S2 layers in gelatinous fibres) are often not registered or because grey scales that are not cell walls (e.g. gums in vessels, some substances in parenchyma cells) are recognized as such. Thus, despite the overall good quality of the sections (15–20 µm thick), there is an important source of error in the total cell wall area proportion we analysed.

We decided to analyse diffuse- and ring-porous woods together because the latter only represented little over 11 % of the total number of species. However, to provide further support for our results, we also analysed diffuse-porous species alone since wood traits, especially those related to vessel variation, could differ between earlywood and latewood in ring-porous species. As we did not find any significant difference in our analysis between the whole data set and the partition using only diffuse-porous species, we emphasize the results from the whole data set in the discussion. Parallel findings by Zanne et al. (2010) showed no divergent associations among traits in the diffuse-porous woods and combined data sets in a global analysis including >3000 species.

It is important to highlight that ray area is a very broad parameter that can be achieved by many means and most probably hides some functional strategies. A high proportion of rays, for example, can be achieved by having a large number of uniseriate rays or a few multiseriate rays (or both), with different mechanical and hydraulic implications. At a given ray cross-sectional area, the presence of a few broad rays, especially in woody temperate angiosperms (Braun, 1970, 1984), would be translated into a proportionally lower number of contact cells (cells having functional connections with vessels) and a proportionally higher number of isolation cells (which are more involved in radial translocation; Sauter and Kloth, 1986) compared with species with the same cross-sectional area composed of many narrow rays. This differential proportion would conceivably influence hydraulic aspects such as embolism repair capacity or transport of osmotically active substances during the mobilization phase in early spring (Braun, 1984), as well as differences in mechanical properties since broad and narrow rays may differ in this regard (Mattheck and Kubler, 1995). As we found in preliminary analyses that the negative association of ray area with transport efficiency traits could be the product of a large proportion of wide-rayed species with a comparatively high number of isolation cells, we further partitioned our analyses into diffuse-porous species with rays ≤5 and >5 cells wide.

To describe different aspects of water conduction, we calculated F and S vessel metrics developed by Zanne et al. (2010). F, the product of mean vessel size ( ) times vessel number per unit area (N), measures the fraction of wood that is occupied by vessel space (

) times vessel number per unit area (N), measures the fraction of wood that is occupied by vessel space ( ; mm2 mm−2). Increases in F should be correlated with lower mechanical strength (Jacobsen et al., 2005; Preston et al., 2006; Zanne et al., 2010). S is the ratio of the same anatomical traits (

; mm2 mm−2). Increases in F should be correlated with lower mechanical strength (Jacobsen et al., 2005; Preston et al., 2006; Zanne et al., 2010). S is the ratio of the same anatomical traits ( ; mm4.) and measures the variation in vessel composition. Higher S indicates a greater contribution of large vessels to water conduction in a given area (Zanne et al., 2010) and therefore indicates increased water capacity and increased risk of cavitation. These two metrics represent orthogonal axes of variation (Zanne et al., 2010). Using vessel lumen fraction (F) and the vessel composition metric (S), we calculated potential conductivity (Ks) as

; mm4.) and measures the variation in vessel composition. Higher S indicates a greater contribution of large vessels to water conduction in a given area (Zanne et al., 2010) and therefore indicates increased water capacity and increased risk of cavitation. These two metrics represent orthogonal axes of variation (Zanne et al., 2010). Using vessel lumen fraction (F) and the vessel composition metric (S), we calculated potential conductivity (Ks) as

For details on the derivation of this equation, see Zanne et al. (2010). The relationship between wood density and tissue proportions was based on 408 species, while the relationship among Ks, S and F was based on the entire data set (794 species). To analyse these relationships, we matched the anatomical traits with wood density by species name.

Statistical analysis

To determine patterns of correlated evolution between the wood anatomical traits and functional variables, we used phylogenetically independent contrasts (PICs). We also present the phylogenetically uninformed (raw) correlations for the full data set in the Supplementary Data Table S1; these were calculated using R (R Development Core Team, 2008). The phylogenetic relationships among species were reconstructed using the program PHYLOMATIC (Webb and Donoghue, 2005), which resulted in a polytomous tree. For the PIC analysis, we treated polytomies as soft and reduced the degrees of freedom accordingly (Purvis and Garland, 1993; Garland and Díaz-Uriarte, 1999). Branch lengths of the resulting tree (prior to the actual PIC analysis) were calculated using the branch length-adjusting algorithm (bladj) implemented in the program PHYLOCOM (Webb et al., 2007). To calibrate the phylogenetic tree, we used angiosperm node ages provided in Wikstrom et al. (2001). The resulting tree was used for the PIC analysis. Characters not adequately standardized (i.e. the absolute values of the standardized PICs and their standard deviations showed a significant association) were log (continuous) or arcsine (proportions) transformed as suggested by Garland et al. (1991, 1992). We used the module PDAP:PDTREE (Midford et al., 2005) in the program Mesquite (version 2·75; Maddison and Maddison, 2008) to calculate the PIC correlations.

To explore how axes of variation representing mechanical strength, storage and water conduction related to each other in a phylogenetic framework, we performed a phylogenetic principal component analysis (pPCA; Jombart et al., 2010). A pPCA describes overall patterns of phylogenetic signal. This variant of pPCA has a similar methodological framework to that used in spatial ecology (Dray et al., 2008) and detects non-independent values of variables in relation to the phylogenetic relationship (phylogenetic autocorrelation) between species. This phylogenetic autocorrelation can be positive or negative. Positive autocorrelation or global structure is the result of global patterns of similarity in related taxa. Negative phylogenetic autocorrelation, or local structure, results from differences among closely related species in the tips of the phylogeny. These structures are detected using Moran's index (I). In a pPCA analysis, the largest eigenvalues are those with large variance and large positive Moran's I, and correspond to global structure that reflects divergence of traits close to the root of the tree. The most negative eigenvalues are those with high variance and large negative Moran's I; these local structures correspond to recent divergence. Phylogenetic proximities, based on the phylogenetic distances of the tree described above, were calculated using Abouheif's proximity (Abouheif, 1999; Pavoine et al., 2008). The resulting matrix of phylogenetic proximities was used to calculate phylogenetic autocorrelation (Jombart et al., 2010). The pPCA was carried out using adephylo (Jombart et al., 2009). We analysed the four data partitions (i.e. full data sets, and data sets for only diffuse-porous woods, and woods with rays ≤5 and >5 cells wide) and then compared their results by regressing the loadings, among analyses, of wood anatomical traits, Ks, S and F, on each of the three first principal components.

RESULTS

Phylogenetically independent contrast results vs. phylogenetically uninformed analyses in the full data set

Phylogenetically informed and uninformed correlations yielded very similar results. The few exceptions were (1) the correlation between wood density and total parenchyma, which was not significant using PICs; wood density was only significantly correlated with (2) vessel diameter and (3) S in the PIC analysis; (4) the proportion total parenchyma and potential conductivity was recognized as significant in the PIC; and S was only significantly associated with (5) ray area and (6) total parenchyma area in the phylogenetically uninformed analysis (Supplementary Data Table S1; Table 1). Here we describe phylogenetically informed analysis unless otherwise stated.

Table 1.

Phylogenetically independent contrast correlations between functional traits and wood anatomy in the full data set

| Wood density (n = 404) | Ks (n = 793) | S (n = 793) | F (n = 793) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vessel density | –0·036 | –0·3**** | –0·93**** | 0·42**** |

| Vessel diameter | –0·14** | 0·82**** | 0·93**** | 0·3**** |

| Vessel area | –0·08 | 0·39**** | –0·12**** | 0·64**** |

| Cell wall area | 0·3**** | –0·24**** | –0·05 | –0·3**** |

| Fibre area | 0·04 | –0·25**** | 0·06* | –0·4**** |

| Ray area | 0·13** | –0·15**** | –0·01 | –0·2**** |

| Axial parenchyma area | –0·11** | 0·15**** | 0·16**** | 0·05 |

| Total parenchyma area | 0·06 | –0·087* | 0·06 | –0·18**** |

| Ks | –0·15** | – | – | – |

| S | –0·1* | 0·59**** | – | – |

| F | –0·12*** | 0·67**** | –0·07* | – |

****P < 0·0001; ***P < 0·001; **P < 0·01; *P < 0·05

n = number of species used in the PIC correlation analysis.

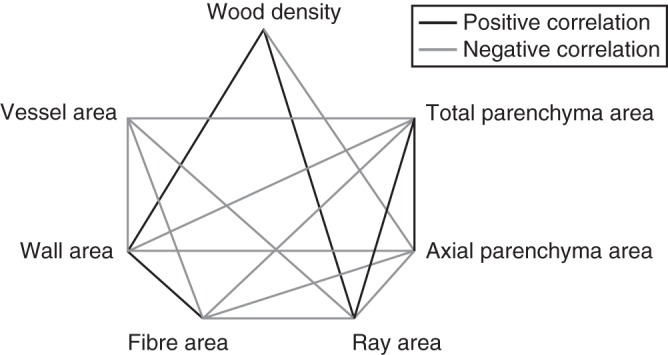

Relationship between wood density and tissue proportions

The main anatomical determinant of wood density was the total area proportion of cell walls. Surprisingly, the area of fibres in cross-sections was not associated with wood density. Instead, wood density significantly increased with the proportion of rays in cross-section and decreased with axial parenchyma (Fig. 1, Table 1). Total parenchyma, the sum of axial and radial parenchyma, was independent from wood density because parenchyma types vary in opposite directions, cancelling each other out. Vessel area was also independent from wood density (Fig. 1, Table 1). No difference between wood density and wood anatomy traits were detected between the full data set and that including only diffuse-porous species. In the data set including only species with rays ≤5 cells wide, the relationship of wood density and vessel diameter, axial parenchyma and S is no longer significant. However, some traits such as cell wall area and ray area are more tightly correlated with wood density in this last data partition when compared with the full data set. In the species with rays >5 cells wide (n = 46), none of the traits was significantly associated with wood density (Supplementary Data Table S2).

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing significant (P < 0·05) PIC correlations among wood density and cell type areas in cross-section. Lines indicate significant relationship between variables. Positive and negative correlations are as indicated in the key.

Relationship among tissue proportions

As expected, most of the relationships among tissue proportions were negative (Fig. 1) because the increase in one cell type should be at the expense of others. The only positive associations were between cell wall area and proportion of fibres, and between ray and axial parenchyma and total parenchyma area. Only two pairs of traits were not correlated: vessel area varied independently of axial parenchyma area, and cell wall area and ray areas were also independent. We did not detect any change in phylogenetic correlations, other than the reduction of significance values with decreasing number of species, among tissue proportions among data partitions (results not shown).

Relationship of Ks, F and S with tissue proportions

Ks increased with vessel and axial parenchyma area and decreased with total parenchyma, ray, fibre and cell wall areas (Table 1). Ks was negatively associated with wood density (Table 1). Vessel composition metric S was positively associated with fibre and axial parenchyma areas and negatively associated with vessel area. Vessel fraction F was positively associated with vessel area and negatively with total parenchyma and ray, fibre and wall area, and varied independently of axial parenchyma (Table 1). As expected, both S and F were positively related to potential conductivity, and their relationship with wood density was negative, although less significant (Table 1). We detected only one difference between the full data set and the partition including only diffuse-porous woods (Supplementary Data Table S2): the relationship between Ks and proportion of total parenchyma (–0·087 vs. –0·07) became non-significant. In the data set including rays ≤5 cells wide, the proportion of fibres was no longer associated with Ks, but it was tightly associated with S (Supplementary Data Table S2). In species with ray width >5 cells, fibre, ray, axial parenchyma and total parenchyma areas were no longer associated with Ks, and fibre area is not correlated with S (Supplementary Data Table S2).

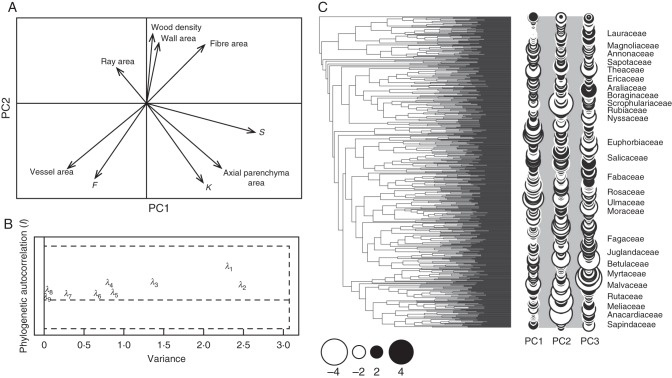

Phylogenetic principal component analysis

We did not detect negative Moran's I values; therefore, local structures representing divergence in trait values among closely related species were not obvious in our sample (Fig. 2B). The first three principal components (first three global structures) explained 93 % of the trait variation. In the first phylogenetic principal component (pPCA1), traits with higher loadings were the proportion of vessels, axial parenchyma and S, and, with somewhat lower loadings, Ks (Fig. 2A). This axis describes hydraulic efficiency and storage capacity, with species occupying the right side having comparatively fewer larger vessels (higher S), lower area occupied by vessels, higher potential conductance and larger amount of axial parenchyma than species in the left side of the pPCA plot (Fig. 2). Lineages with highly efficient water conduction and high amount of axial parenchyma include Fabaceae (Fabales), Moraceae (Rosales), Bombacoideae (Malvales) and Scrophulariaceae (Lamiales), while more inefficient water transport and lower amounts of parenchyma are present in Cercidiphyllaceae, Hamamelidaceae (Saxifragales), Rosaceae, Rhamnaceae, Ulmaceae (Rosales), Salicaceae (Malpighiales), Ericaceae and Theaceae (Ericales) (Fig. 2C). In the second pPCA axis, from top to bottom in Fig. 2A, species decrease in wood density and proportion of cell wall area, and increase in conduction capacity (Ks), proportion of axial parenchyma and vessel fraction (Fig. 2A). This axis describes a trade-off between mechanical support and conduction efficiency. Among the families with low wood density, high water conduction and high axial parenchyma proportions are Schrophulariaceae and Bignoniaceae (both in Lamiales), Fabaceae, Moraceae, and Rutaceae and Anacardiaceae (in Sapindales). Rosaceae, Fagaceae, Rubiaceae and Salicaceae, among others, have higher wood density, lower conduction capacity and lower amount of parenchyma. In the third pPCA, wood density and proportions of rays and fibres have the highest loadings; this axis could be interpreted as a radial mechanical strength axis (see discussion below). Myrtaceae (Myrtales), Fagaceae, Clusiaceae (Malpighiales), Salicaceae and Ulmaceae are among the families with high wood density and ray area, while, among others, Araliaceae, Lauraceae and Moraceae showed lower values of both of these anatomical variables (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

pPCA of anatomical, wood density and potential conduction data. (A) pPCA plot of the first and second principal component (global structures). (B) Eigenvalue decomposition showing phylogenetic autocorrelation (Moran's I) as a function of variance for each one of the eigenvalues (λ). (C) Phylogenetic tree used in this study and the three first global structures. Positive and negative scores are indicated by black and white circles, respectively; symbol size is proportional to absolute scores values.

The results of the pPCA were highly congruent among all four data partitions when judged by the significant determination coefficients of trait loadings among analyses (Supplementary Data Table S3 and Fig. S1). This resemblance was especially high in the first pPCA axis and lowest, but still very significant, in the third pPCA axis (Supplementary Data Table S3). As expected, the highest resemblance was between the full data set and the data set of only diffuse-porous species (R2 > 0·95, P < 0·0001 for loadings in the three first three PCA axes; Supplementary Data Table S3). The pPCA including only species with rays >5 cells wide had a larger deviation in loadings compared with the full data set, most probably due to the less tight association among variables as exhibited by the PIC analysis results. This analysis (rays >5 cells wide) essentially showed a trade-off between wood density and space occupied by vessels (F and vessel area) in the first global structure, and an orthogonal trade-off between wood density, conduction capacity and storage capacity (amount of both axial and radial parenchyma) in the second pPCA axis (Supplementary Data Fig. S1). In this second pPCA axis, conduction capacity is directly related to the proportion of both parenchyma types.

DISCUSSION

Xylem parenchyma has long been recognized as the storage compartment of wood (e.g. Sauter and van Cleve, 1994; Wheeler et al., 2007), and both parenchyma types, axial and radial, have also been repeatedly implicated in embolism repair (e.g. Tyree et al., 1999; Ameglio et al., 2001; Salleo et al., 2004). Living parenchyma also produces secondary metabolites that serve as a defence mechanism against pathogens (Wheeler et al., 2007). Here we present evidence that different parenchyma types have contrasting patterns of correlated evolution with wood density and water conduction properties, suggesting some degree of functional differentiation between them. Axial parenchyma was negatively related to wood density and positively associated with potential conductivity and the vessel composition metric S. Rays, on the other hand, were positively associated with wood density and negatively associated with potential conductivity and vessel fraction F. This pattern indicates that ray proportion varies directly with increased support (wood density), while axial parenchyma is directly related to increased conduction capacity.

Rays have been related to radial transport of Münch-water between phloem and xylem (Van Bel, 1990; Milburn, 1996; Höltta et al., 2006) and storage of water, sugar and other nutrients (Sauter and van Cleve, 1994), but their mechanical significance has been explored only recently (Mattheck and Kubler, 1995; Burgert et al., 1999; Burgert and Eckstein, 2001). Burgert et al. (1999) experimentally demonstrated that under controlled radial tensile loads, the direction of growth of radial tissue shifted parallel to the applied force, suggesting that rays are mechanically functional. Additionally, microtensile experiments showed that radial strength of isolated rays was three times higher than radial strength of wood as a whole; most probably, this difference would be even greater when compared with axial tissue alone (Burgert and Eckstein, 2001). Rays also influence the radial MOE since there is a direct relationship between this mechanical parameter and the proportion of ray area in cross-section (Burgert and Eckstein, 2001).

The importance of rays in radial mechanical strength described above, together with our result showing that the proportion of rays is larger in denser woods, indicate that a high prevalence of ray parenchyma appears to contribute to stem radial mechanical stability. However, the relationship between mechanical strength and ray proportion is probably more complex than the one we depicted above. We have assumed that wood density is linked to mechanical strength and stiffness [MOE and modulus of rupture (MOR)] as has been shown in some studies (e.g. Pratt et al., 2007), but mechanical strength at the tissue level is not necessarily good for whole tree support efficiency (Larjavaara and Muller-Landau, 2010). In addition, in one of the few studies that measure anisotropy (mechanical response of wood along and across the grain) in wood properties, Guitard and El Amri (1987) found that while a higher proportion of rays increases the radial MOE it also limits the longitudinal MOE for a given wood density, and longitudinal properties are the most important mechanical determinants in stems. Paradoxally, Woodrum et al. (2003) have found among Acer species a high correlation between percentage of ray parenchyma and axial bending MOE, and discussed this coincidental relationship, opposed to physics, in connection with the hard maple ecology. A comprehensive study of how longitudinal and radial MOE and MOR interact simultaneously to determine stem support efficiency remains to be carried out.

Martínez-Cabrera et al. (2009) suggested a possible functional divergence between axial and ray parenchyma because they showed opposite correlation patterns with wood density and climate. They found higher proportions of rays and lower axial parenchyma in species with low wood density from wet sites, while the opposite was true for dry areas. Because rays can be involved in embolism repair (Tyree et al., 1999), these authors suggested that the lower proportion of rays (and low contact between rays and vessels) associated with high-density xylem in species from arid regions could be related to a detrimental effect of embolism repair involving Münch-water in extremely dry sites. Since rays transport water across sections in stems (Hölttä et al., 2006), water used to repair embolized vessels must come from other stem regions. Because of this, when drought is prolonged, embolism repair could be detrimental to plants as stem water lost through transpiration would occur in the absence of tissue rehydration due to environmental water deficit (Martínez-Cabrera et al., 2009). Here, however, we found, as has been found in other studies (e.g. Taylor, 1969; Rahman et al., 2005), the opposite pattern: a higher ray area occurs in species with high wood density. The difference between the results presented here and those of Martínez-Cabrera et al. (2009) might be explained because they analysed shrubs from drier areas while we included only trees from relatively mesic sites. It is unlikely that the disadvantage of ray tissue in very dry environments described above is relevant to our samples from wetter sites. Alternatively, the difference between the two studies in the relationship between wood density and the proportion of ray parenchyma may be a function of the differences in growth forms. Wood of trees and shrubs has been shown to differ in several other traits (e.g. Wheeler et al., 2007; Jacobsen et al., 2012), including evolutionary integration of wood density, height and vessel anatomy (Martínez-Cabrera et al., 2011).

Another interesting aspect of our results is that ray proportion is negatively related to Ks despite being involved in embolism repair (Table 1). This suggests that conduction efficiency and potential for repair (given by the large amount of ray tissue) are either negatively related or, most probably, that the mechanical function of rays (given by its relationship to wood density) is driving the negative association between ray proportion and water conduction efficiency at least up to a certain limit (only in narrowly rayed species). In our sub-set of species with rays >5 cells wide, wood density and ray proportion vary in the opposite direction in two different pPCA component axes, indicating that the mechanical link between these two traits is probably lost when rays are very wide. Moreover, in this same data partition, ray proportion increases, in the multivariate space, with conduction capacity, suggesting that perhaps the function of the rays varies with their size. That is, a high ray area in narrowly rayed species is associated with increased mechanical strength, while a high ray area in wide-rayed species is more tightly associated with traits conferring increased conductance. This result is exactly the opposite to our expectation of narrow rays being more involved in hydraulic aspects than wide rays (Sauter and Kloth, 1986) because of their higher number of contact cells. We should mention, however, that the relationships of rays to wood density and Ks are not longer recognized for the wide-rayed group in the PIC correlations.

An alternative explanation to the negative relationship between wood density and axial parenchyma area and axial parenchyma and ray areas could be, again, related to anisotropy without having to involve the ray's role in hydraulics. That is, as axial parenchyma weakens longitudinal strength, increases in ray area would avoid diminished mechanical strength and maintain high storage capacity when axial parenchyma area decreases. This alternative hypothesis and the one above relating the variation patterns we found here to the hydraulic role of rays remain to be tested.

Our analysis also indicates that axial parenchyma, and presumably storage and embolism repair function, is directly correlated with conduction efficiency and negatively with wood density. Wood density is often inversely related to relatively small declines in stem water potential and stem water storage (Borchert, 1994). This relationship emerges because the withdrawal of water from intracellular storage compartments lessens the decline in water potential during periods of reduced water availability (Holbrook et al., 1995). Presumably, axial parenchyma provides the water storage capacity associated with low wood density. In temperate and tropical trees, capacitance during dehydration (water storage capacity) and the amount and distribution of axial parenchyma are positively correlated. In a recent study, deciduous hardwood species with imperforate tracheary elements enclosing vessels had low water storage capacitance, whereas stem succulent species with abundant paratracheal axial parenchyma had high capacitance (Borchert and Pockman, 2005). Correspondingly, deciduous hardwoods had higher wood density than succulents. These differences observed also corresponded to two main seasonal drought strategies: drought tolerance vs. drought avoidance. Drought tolerators have small amounts of axial parenchyma and are highly tolerant to low water potentials, while in drought avoiders, with large amounts of paratracheal axial parenchyma, the probability of cavitation is low despite high water loss (Borchert et al., 1994; Goldstein et al., 1998). Species with extensive paratracheal axial parenchyma, often drought avoiders, have low cavitation even though up to 20 % of water in stem water is transpired daily (Machado and Tyree, 1994; Goldstein et al., 1998). This relationship between the amount of axial parenchyma and cavitation suggests that it is part of a suite of traits that are involved in the trade-off between conduction efficiency and cavitation resistance, in which axial parenchyma is either buffering cavitation or involved in embolism repair (e.g. Tyree et al., 1999). The positive relationship between axial parenchyma area and hydraulic efficiency we showed here suggests that axial parenchyma might be linked to efficient conduction with storage/repair capacity in relatively mesic trees.

The lack of more clearly defined axes of variation in our pPCA analysis could be due to several reasons, the most important being that the anatomical traits we measured have high functional complexity and, in many cases, are important in performing more than one function. For instance, the multiple functions of some cell types can lower our power to detect the axes of variation clearly. For example, the cytoplasmatic contents in septate (living) fibres (e.g. Vestal and Vestal, 1940; Spackman and Swamy, 1949) together with their high incidence in woods with scanty parenchyma (Spackman and Swamy, 1949; Wheeler et al., 2007) suggest that living fibres have a dual function of storage and mechanical support (Govindarajaru and Swamy, 1955; Wheeler et al., 2007). A similar complexity is represented by rays and axial parenchyma which have links to the three aspects: wood mechanics, storage and hydraulics. Another source of error in our analyses is introduced by inaccuracies of the image analysis in measuring total cell wall area; this is likely to be behind the low proportion in wood density explained by cell wall area (9 %).

The predominance of global structures in the pPCA indicates a high phylogenetic signal in the three PCA axes. Trait divergence among closely related taxa was not large in our study, as we did not detect local structures. Jombart et al. (2010) suggested that low eigenvalues of local structures can still be interpreted because Moran's I distribution is asymmetric (negative values often have a smaller range of variation than positive values) and pPCA would more easily detect extreme autocorrelation associated with global structures than the less extreme negative values of local structures (Jombart et al., 2010). Interestingly, most of the anatomical traits that had high values in the three first local structures are related to water conduction, indicating that water conduction characteristics tend to vary among closely related taxa more than traits associated with mechanical support. However, as none of the eigenvalues was negative (below the dashed line in Fig. 2B), the evolution of these water conduction traits is not clearly divergent.

Conclusions

The pPCA provided parallel information to the PIC analysis. The first pPCA represents a water conduction and storage (and possibly repair) axis. In this component, species varied from hydraulically efficient with high storage capacity to hydraulically inefficient with low storage capacity. The second global component integrates conduction capacity, storage and support, and thus represents the trade-off between conduction efficiency, wood density and cavitation resistance seen in many studies (e.g. Hacke et al., 2001, 2006). The third global structures represent the radial mechanical strength axis, with wood density and proportion of rays varying together. However, as mentioned earlier, the importance of some traits in more than one component indicates a greater complexity of variation and is probably the reason why we did not detect very clear axes of variation (especially in the second pPCA axis). Given the nature of our study, the axis co-ordination presented here should be taken as a starting point for other studies incorporating wood biomechanics, hydraulics and anatomy, but with greater focus on species variation in particular environments. Although much remains to be investigated regarding the role of anatomical elements with multiple functions (e.g. living fibres, contact and isolation cells in parenchyma), the fact that these functional axes of variation and their anatomical determinants were very conserved across the Chinese lineages we analysed is significant. These functional axes were possibly established very early in the history of the angiosperms, indicating their significance in the functional strategies of the group.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Cynthia Jones and John Silander for their valuable suggestions on the draft and their help with the English language of this manuscript, and Dr Xiangping Wang for his help in data collection and discussion. We also acknowledge the helpful comments of two anonymous reviewers. This work was supported by the China Ministry of Science and Technology under Contract (2011CB403201) to J.Z. H.I.M.C. thanks CONACYT and FQRNT for support.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abouheif E. A method for testing the assumption of phylogenetic independence in comparative data. Evolutionary Ecology Research. 1999;1:895–909. [Google Scholar]

- Améglio T, Ewers FW, Cochard H, et al. Winter stem pressures in walnut trees: effects of carbohydrates, cooling and freezing. Tree Physiology. 2001;21:384–394. doi: 10.1093/treephys/21.6.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Améglio T, Bodet C, Lacointe A, Cochard H. Winter embolism, mechanisms of xylem hydraulic conductivity recovery and springtime growth patterns in walnut and peach trees. Tree Physiology. 2002;22:1211–1220. doi: 10.1093/treephys/22.17.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad H, Herbette S, Brunel N, et al. No trade-off between hydraulic and mechanical properties in several transgenic poplars modified for lignins metabolism. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2012;77:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert R. Water storage in soil or tree stems determines phenology and distribution of tropical dry forest trees. Ecology. 1994;75:1437–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert R, Pockman WT. Water storage capacitance and xylem tension in isolated branches of temperate and tropical trees. Tree Physiology. 2005;25:457–466. doi: 10.1093/treephys/25.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun HJ. Funktionelle Histologie der sekundaaren Sprossachse. I. Das Holz. Handbuch der pflanzenanatomie(Encyclopedia of plant anatomy) Berlin: Borntraeger; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Braun HJ. The significance of the accessory tissues of the hydrosystem for water shifting as the second principle of water ascent, with some thoughts concerning the evolution of trees. IAWA Bulletin. 1984;5:275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Bucci SJ, Scholz FG, Goldstein G, Meinzer FC, Sternberg LDSL. Dynamic changes in hydraulic conductivity in petioles of two savanna tree species: factors and mechanisms contributing to the refilling of embolized vessels. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2003;26:1633–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Burgert I, Eckstein D. The tensile strength of isolated wood rays of beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and its significance for the biomechanics of living trees. Trees. 2001;15:168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Burgert I, Bernasconi A, Eckstein D. Evidence for the strength function of rays in living trees. Holz als Roh Werkstoff. 1999;57:397–399. [Google Scholar]

- Canny M. Vessel contents during transpiration – Embolism and refilling. American Journal of Botany. 1997;84:1223–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlquist S. Comparative wood anatomy: systematic, ecological, and evolutionary aspects of dicotyledon wood. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J-Q, Yang J-J, Liu P. Anatomy and properties of Chinese woods. Beijing: Forestry Publishing House; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dray S, Saïd S, Debias F. Spatial ordination of vegetation data using a generalization of Wartenberg's multivariate spatial correlation. Journal of Vegetation Science. 2008;19:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Enquist BJ, West GB, Chernov EL, Brown JH. Allometric scaling of production and life history variation in vascular plants. Nature. 1999;401:907–911. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Di'az-Uriarte R. Polytomies and phylogenetically independent contrasts: an examination of the bounded degrees of freedom approach. Systematic Biology. 1999;48:547–558. doi: 10.1080/106351599260139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Harvey PH, Ives AR. Procedures for the analysis of comparative data using phylogenetic independent contrasts. Systematic Biology. 1992;41:18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Garland T, Jr, Harvey PH, Bennett AF. Phylogeny and thermal physiology in lizards: a reanalysis. Evolution. 1991;45:1969–1975. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb02703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner BL. Structural stability and architecture of vines vs shrubs of poison oak. Toxicodendron diversilobum. Ecology. 1991;72:2005–2015. doi: 10.1007/BF00325255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner BL, Lei H, Milota MR. Variation in the anatomy and specific gravity of wood with and between trees of red Alder. Wood and Fiber Science. 1997;29:10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein G, Andrade JL, Meinzer FC, et al. Stem water storage and diurnal patterns of water use in tropical forest canopy trees. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1998;21:397–406. [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajaru B, Swamy BGL. Size variation of septate wood fibres in Pithecellobium dulce Benth. Nature. 1955;176:4476. [Google Scholar]

- Guitard D, El-amri F. Actes du 2e Colloque des Sciences et Industries du Bois, 22–24 April 1987. Nancy: France; 1987. La fraction volumique en rayons ligneux comme paramètre explicatif de la variabilité de l'anisotropie élastique du matériau bois. [Google Scholar]

- Hacke UG, Sperry JS, Pockman WT, Davis SD, McCulloch KA. Trends in wood density and structure are linked to prevention of xylem implosion by negative pressure. Oecologia. 2001;126:457–461. doi: 10.1007/s004420100628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacke UG, Sperry JS, Wheeler JK, Castro L. Scaling of angiosperm xylem structure with safety and efficiency. Tree Physiology. 2006;26:619–701. doi: 10.1093/treephys/26.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook NM. Stem water storage. In: Gartner BL, editor. Plant stems: physiology and functional morphology. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hölttä T, Vesala T, Perämȧki M, Nikinmaa E. Refilling of embolised conduits as a consequence of ‘Münch water’ circulation. Functional Plant Biology. 2006;33:949–959. doi: 10.1071/FP06108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen AL, Ewers FW, Pratt RB, Paddock WA, Davis SD. Do xylem fibers affect vessel cavitation resistance? Plant Physiology. 2005;139:546–556. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen AL, Agenbag L, Esler KJ, Pratt RB, Ewers FW, Davis SD. Xylem density, biomechanics and anatomical traits correlate with water stress in 17 evergreen shrub species of the Mediterranean-type climate region of South Africa. Journal of Ecology. 2007;95:171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen AL, Pratt RB, Tobin MF, Hacke UG, Ewers FW. A global analysis of xylem vessel length in woody plants. American Journal of Botany. 2012;99:1583–1591. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1200140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombart T, Balloux F., Dray S. adephylo: new tools for investigating the phylogenetic signal in biological traits. Bioinformatics. 2009;26:1907–1909. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jombart T, Pavoine S, Devillard S, Pontier D. Putting phylogeny into the analysis of biological traits: a methodological approach. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2010;264:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DA, Davies SJ, Nur Supardi MN, Tan S. Tree growth is related to light interception and wood density in two mixed dipterocarp forest of Malaysia. Functional Ecology. 2005;19:445–453. [Google Scholar]

- King DA, Davies SJ, Tan S, Supardi N., Noor M. The role of wood density and stem support costs in the growth and mortality of tropical trees. Journal of Ecology. 2006;94:670–680. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski TT. Carbohydrate sources and sinks in woody plants. Botanical Reviews. 1992;58:107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Larjavaara M, Muller-Landau HC. Rethinking the value of high wood density. Functional Ecology. 2010;24:701–705. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei H, Milota MR, Gartner BL. Between- and within-tree variation in the anatomy and specific gravity of wood in Oregon white oak (Quercus garryana Dougl.) IAWA Journal. 1996;17:445–461. [Google Scholar]

- Machado JL, Tyree MT. Patterns of hydraulic architecture and water relations of two tropical canopy trees with contrasting leaf phenologies: Ochroma pyramidale and Pseudobombax septenatum. Tree Physiology. 1994;14:219–240. doi: 10.1093/treephys/14.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis, version 2·5. 2008 http://mesquiteproject.org . [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cabrera HI, Jones C S, Espino S, Schenk HJ. Wood anatomy and wood density in shrubs: responses to varying aridity along transcontinental transects. American Journal of Botany. 2009;96:1388–1398. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0800237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Cabrera HI, Schenk HJ, Cevallos-Ferriz SRS, Jones CJ. Integration of vessel trait, wood traits and height in angiosperm shrubs and trees. American Journal of Botany. 2011;98:915–922. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattheck C, Kubler H. Wood – the internal optimization of trees. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Midford PE, Garland TJ, Maddison WP. PDAP package of Mesquite, version 1·06. 2005 http://mesquiteproject.org/pdap_mesquite/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- Milburn JA. Sap ascent in vascular plants: challengers to the cohesion theory ignore the significance of immature xylem and the recycling of Münch water. Annals of Botany. 1996;78:399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Landau HC. Interspecific and intersite variation in wood specific gravity of tropical trees. Biotropica. 2004;36:20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nock C, Geihofer D, Grabner M, Baker PJ, Bunyavejchewin S, Hietz P. Wood density and its radial variation in six canopy tree species differing in shade-tolerance in western Thailand. Annals of Botany. 2009;104:297–306. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavoine S, Ollier S, Pontier D, Chessel D. Testing for phylogenetic signal in a life history variable: Abouheif's test revisited. Theoretical Population Biology. 2008;73:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tpb.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt RB, Jacobsen AL, Ewersä FW, Davis SD. Relationships among xylem transport, biomechanics and storage in stems and roots of nine Rhamnaceae species of the California chaparral. New Phytologist. 2007;174:787–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston KA, Cornwell WK, DeNoyer JL. Wood density and vessel traits as distinct correlates of ecological strategy in 51 California coast range angiosperms. New Phytologist. 2006;170:807–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis A, Garland T., Jr Polytomies in comparative analyses of continuous characters. Systematic Biology. 1993;42:569–575. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. http://www.r-project.org . [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MM, Fujiwara S, Kanagawa Y. Variations in volume and dimensions of rays and their effect on wood properties of teak. Wood and Fiber Science. 2005;37:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Roderick ML. On the measurement of growth with applications to the modelling and analysis of plant growth. Functional Ecology. 2000;14:244–251. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe N., Speck T. Plant growth forms: an ecological and evolutionary perspective. New Phytologist. 2005;166:61–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldarriaga JG, West DC, Tharp ML, Uhl C. Long-term chronosequence of forest succession in the upper Rio Negro of Colombia and Venezuela. Journal of Ecology. 1988;76:938–958. [Google Scholar]

- Salleo S, Lo Gullo MA, Trifilò P, Nardini A. New evidence for a role of vessel-associated cells and phloem in the rapid xylem refilling of cavitated stems of Laurus nobilis L. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2004;27:1065–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Sauter JJ, Kloth S. Plasmodesmatal frequency and radial translocation rates in ray cells of poplar (Populus canadensis Moench ‘robusta’) Planta. 1986;168:377–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00392363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter JJ, van Cleve B. Storage, mobilization and interrelations of starch, sugars, protein and fat in the ray storage tissue of poplar trees. Trees. 1994;8:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Spackman W, Swamy BGL. The nature and occurrence of septate fibers in dicotyledons. American Journal of Botany. 1949;36:804. [Google Scholar]

- Sperry JS. Evolution of water transport and xylem structure. International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2003;164:S115–S127. [Google Scholar]

- Swaine MD, Whitmore TC. On the definition of ecological species groups in tropical rain forests. Plant Ecology. 1988;75:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor F. The effect of ray tissue on the specific gravity of wood. Wood and Fiber Science. 1969;1:142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Steege H, Hammond DS. Character convergence, diversity, and disturbance in tropical rain forest in Guyana. Ecology. 2001;82:3197–3212. [Google Scholar]

- Tyree MT, Salleo S, Nardini A, Lo Gullo MA, Mosca R. Refilling of embolized vessels in young stems of laurel: do we need a new paradigm? Plant Physiology. 1999;120:11–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bel AJE. Xylem–phloem exchange via the rays: the undervalued route of transport. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1990;41:631–644. [Google Scholar]

- Vestal PA, Vestal MR. The formation of septa in the fibre-tracheids of Hypericum androsaemum L. Harvard University Botanical Museum Leaflets. 1940;8:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Webb CO, Donoghue MJ. Phylomatic: tree assembly for applied phylogenetics. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2005;5:181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Webb CO, Ackerly DD, Kembel SW. Phylocom: software for the analysis of community phylogenetic structure and trait evolution, version 3·41. Bioinformatics. 2007;24:2098–2100. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann MC, Williamson GB. Extreme radial changes in wood specific gravity in some tropical pioneers. Wood and Fiber Science. 1988;20:344–349. [Google Scholar]

- Wiemann MC, Williamson GB. Radial gradients in the specific gravity of wood in some tropical and temperate trees. Forest Science. 1989;35:197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler EA, Bass P, Rodgers S. Variations in dicot wood anatomy: a global analysis based on the InsideWood database. IAWA Journal. 2007;28:229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wikstrom N, Savolainen V, Chase MW. Evolution of angiosperms: calibrating the family tree. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2001;268:2211–2220. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock D, Shier A. Wood specific gravity and its radial variations: the many ways to make a tree. Trees. 2002;16:432–443. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrum CL, Ewers FW, Telewski FW. Hydraulic, biomechanical, and anatomical interactions of xylem from five species of Acer (Aceraceae) American Journal of Botany. 2003;90:693–699. doi: 10.3732/ajb.90.5.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Yang J-J. Physical and mechanical properties of angiosperm in China. China Wood Notes. 2001;71:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-J, Lu H-J. Study on wood characteristics and their frequencies of occurrence in some important Chinese wood species. Scienta Silvae Sinicae. 1993;29:537–543. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-J, Cheng F, Lu H-J. A method for abbreviating woody plant family names. Scienta Silvae Sinicae. 1992;28:376–381. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J-J, Cheng F, Yang J, Lu H-J. Wood identification and anatomy of major tree species in China. Beijing: China Construction and Industry Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zanne AE, Falster DS. Plant functional traits – linkages among stem anatomy, plant performance and life history. New Phytologist. 2010;185:348–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanne AE, Westoby M, Falster DS, et al. Angiosperm wood structure: global patterns in vessel anatomy and their relation to wood density and potential conductivity. American Journal of Botany. 2010;97:207–215. doi: 10.3732/ajb.0900178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q-Y, Fu X-Z, Bao X-R, Lu H-R. Quantitative comparison of wood anatomy between two poplar species by an automatic image analyser. Scienta Silvae Sinicae. 1985;21:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S-B, Ferry Silk JW, Zhang J-L, Cao K-F. Spatial patterns of wood traits in China are controlled by phylogeny and the environment. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2010;20:241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. Chinese physical geography. Beijing: Higher Education Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.