Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine the efficacy and safety of lixisenatide (20 μg once daily, administered before the morning or evening meal) as add-on therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled with metformin alone.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This was a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 680 patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (HbA1c 7–10% [53−86 mmol/mol]). Patients were randomized to lixisenatide morning (n = 255), lixisenatide evening (n = 255), placebo morning (n = 85), or placebo evening (n = 85) injections.

RESULTS

Lixisenatide morning injection significantly reduced mean HbA1c versus combined placebo (mean change −0.9% [9.8 mmol/mol] vs. −0.4% [4.4 mmol/mol]; least squares [LS] mean difference vs. placebo −0.5% [5.5 mmol/mol], P < 0.0001). HbA1c was significantly reduced by lixisenatide evening injection (mean change –0.8% [8.7 mmol/mol] vs. –0.4% [4.4 mmol/mol]; LS mean difference –0.4% [4.4 mmol/mol], P < 0.0001). Lixisenatide morning injection significantly reduced 2-h postprandial glucose versus morning placebo (mean change −5.9 vs. −1.4 mmol/L; LS mean difference −4.5 mmol/L, P < 0.0001). LS mean difference in fasting plasma glucose was significant in both morning (–0.9 mmol/L, P < 0.0001) and evening (–0.6 mmol/L, P = 0.0046) groups versus placebo. Mean body weight decreased to a similar extent in all groups. Rates of adverse events were 69.4% in both lixisenatide groups and 60.0% in the placebo group. Rates for nausea and vomiting were 22.7 and 9.4% for lixisenatide morning and 21.2 and 13.3% for lixisenatide evening versus 7.6 and 2.9% for placebo, respectively. Symptomatic hypoglycemia occurred in 6, 13, and 1 patient for lixisenatide morning, evening, and placebo, respectively, with no severe episodes.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin, lixisenatide 20 μg once daily administered in the morning or evening significantly improved glycemic control, with a pronounced postprandial effect, and was well tolerated.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are subcutaneously injected glucose-lowering agents that are associated with weight loss and have a low propensity to induce hypoglycemia (1,2). The distinct efficacy and safety profile of this class of drugs provides a novel approach for add-on therapy in the event of failure of other antidiabetic agents. The GLP-1 receptor agonists currently available include twice-daily and once-weekly formulations of exenatide and a once-daily formulation of liraglutide, thus providing a broad scope for tailoring therapy to individual patients (3–5).

Lixisenatide is a selective once-daily prandial GLP-1 receptor agonist (6–9) that was approved by the European Medicines Agency in February 2013 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The 20-µg once-daily dose was previously shown to provide the best balance of glucose-lowering efficacy and gastrointestinal tolerability in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin (7). More recently, lixisenatide 20 μg once daily given as monotherapy was shown to significantly improve HbA1c and provide a pronounced effect on postprandial plasma glucose (PPG) in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with lifestyle intervention alone (6).

The efficacy and safety of once-daily morning (prebreakfast) administration of lixisenatide (and twice-daily morning/evening dosing in early studies) have been evaluated in previous clinical studies (6,7,9). If once-daily evening dosing is also effective at reducing HbA1c with similar tolerability, then this would provide patients with increased flexibility to manage their diabetes according to their lifestyle. In the current study (GLP-1 agonist AVE0010 in paTients with type 2 diabetes mellitus for Glycemic cOntrol and sAfety evaLuation with Metformin treatment [GetGoal-M]), we evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of lixisenatide once daily as add-on therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin and, in contrast with other studies, included separate treatment arms looking at prebreakfast administration and pre-evening meal administration.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, four-arm, unbalanced-design, parallel-group, multicenter, multinational study conducted in 133 centers in 16 countries (Australia, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Germany, Croatia, Mexico, Morocco, the Philippines, Romania, Russian Federation, South Africa, Spain, Ukraine, U.S., and Venezuela). The study consisted of a 2-week screening period and a 1-week run-in, followed by a 24-week double-blind treatment phase. This was followed by a placebo-controlled extension of at least 52 weeks primarily collecting long-term safety data, plus a 4-week posttreatment follow-up after treatment discontinuation (not reported here). The primary objective of the study was to assess the efficacy of lixisenatide once daily (subcutaneously injected in the morning prior to breakfast) in terms of HbA1c reduction over 24 weeks versus placebo. Assessment of lixisenatide once daily administered prior to the evening meal was the main secondary objective.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards or ethics committees and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the trial. A data monitoring committee supervised the conduct of the study by an ongoing review of unblinded safety and main efficacy parameters. An allergic reaction adjudication committee (ARAC) performed blinded assessment of potentially allergic or allergic-like reactions. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00712673).

Participants

The study population included patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin with a dose of at least 1.5 g/day for at least 3 months (HbA1c 7–10% [53−86 mmol/mol]). The main exclusion criteria included the following: use of oral or injectable glucose-lowering agents other than metformin within 3 months prior to the time of screening; fasting plasma glucose (FPG) at screening >13.9 mmol/L (250 mg/dL); history of unexplained pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatectomy, stomach/gastric surgery, or inflammatory bowel disease; history of metabolic acidosis, including diabetic ketoacidosis, within 1 year prior to screening; previous allergic reaction to any GLP-1 agonist; and clinically relevant history of gastrointestinal disease, with prolonged nausea and vomiting during the previous 6 months.

Participants were randomized to one of four treatment arms: lixisenatide or placebo injection in the morning or lixisenatide or placebo injection in the evening (3:1:3:1). Patients were stratified by HbA1c values (<8.0/≥8.0% [<64/≥64 mmol/mol]) and BMI (<30/≥30 kg/m2) at screening. Lixisenatide was administered subcutaneously once daily ≤1 h prior to either the morning or evening meal.

End points and assessments

The primary end point was the absolute change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 in the morning injection treatment arm and was assessed in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, which consisted of all randomized patients who received at least one dose of double-blind study treatment and had both a baseline assessment and at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment. The main secondary end point was HbA1c reduction for the evening injection arm.

Secondary end points included baseline to week 24 assessment of the following variables: 1) the percentage of patients achieving HbA1c <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) or ≤6.5% (≤48 mmol/mol); 2) change in FPG; 3) change in body weight; 4) change in 2-h PPG and glucose excursion after a standardized breakfast meal test (morning injection arms only); 5) β-cell function assessed by homeostasis model assessment-B (HOMA-B); and 6) the percentage of patients who required rescue medication. The standardized breakfast meal challenge test consisted of a 600-kcal liquid meal (400 mL of Ensure Plus; Abbott Nutrition, Columbus, OH; composed of 53.8% carbohydrate, 16.7% protein, and 29.5% fat) and was performed 30 min after drug administration at baseline and week 24 (morning arms only).

Safety and tolerability assessment included treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), symptomatic hypoglycemia, local tolerability at the injection site, allergic or allergic-like reactions, suspected pancreatitis, and safety laboratory. The safety population was defined as all randomized patients who took at least one dose of study treatment. For the purpose of this study, symptomatic hypoglycemia was defined as symptoms of hypoglycemia with an accompanying blood glucose <3.3 mmol/L (60 mg/dL) and/or prompt recovery with oral carbohydrate, intravenous glucose, or glucagon injection. Severe symptomatic hypoglycemia was defined as symptomatic hypoglycemia that required the assistance of another person, and that was associated either with a plasma glucose level <2.0 mmol/L (36 mg/dL) or, if no plasma glucose measurement was obtainable, with prompt recovery with carbohydrate, intravenous glucose, or glucagon injection.

Rescue medication was considered if all the fasting self-monitored plasma glucose values in three consecutive days exceeded the prespecified limit, in which case the patient contacted the investigator and a central laboratory FPG measurement (and HbA1c after week 12) was performed. Threshold values were FPG >15.0 mmol/L (270 mg/dL) from baseline to week 8, FPG >13.3 mmol/L (240 mg/dL) from week 8 to 12, and FPG >11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL) or HbA1c >8.5% (>69 mmol/mol) from week 12 to 24. After confirmation of the need for rescue, sulfonylureas were the first option (unless contraindicated when another rescue medication, but not a GLP-1 agonist or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, could be added). Short-term use (up to 5 days at maximum) of insulin therapy (e.g., due to acute illness or surgery) was not considered to be rescue therapy.

The status and concentration of antilixisenatide antibodies were determined at four time points during the main 24-week treatment period (baseline and weeks 2, 4, and 24) using a validated assay (Biacore).

Statistical analyses

The primary efficacy variable was analyzed using an ANCOVA model with treatment arms (morning injection lixisenatide and placebo; evening injection lixisenatide and placebo), randomization strata for screening HbA1c and BMI, and country as fixed effects and using the baseline HbA1c value as a covariate. In the ANCOVA model, the morning and evening injection placebo arms were included as separate treatments but combined as one group when presenting results and making comparisons using the appropriate contrast. A last observation carried forward approach was used to account for missing data by taking the last available postbaseline on-treatment HbA1c measurement as the HbA1c value at week 24. Differences between each lixisenatide arm and the placebo combined group, and their two-sided 95% CIs as well as P values, were estimated within the framework of ANCOVA.

Inclusion of 680 patients (255 in each lixisenatide morning or evening injection arm and 85 in each placebo morning or evening injection arm) was calculated as providing a power of 97% to detect a difference of 0.5% (5.5 mmol/mol) in the absolute change in HbA1c from baseline to week 24 between lixisenatide and placebo.

All continuous secondary variables at week 24 were analyzed using a similar approach with an ANCOVA model as described for the primary efficacy analysis. The categorical secondary variables (percentage of patients with HbA1c <7.0% [<53 mmol/mol] and ≤6.5% [≤48 mmol/mol] and percentage of patients requiring rescue therapy) were analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel method stratified on randomization strata and screening BMI.

RESULTS

Patient flow

A total of 1,374 patients were screened and 680 were randomized to one of the four treatment arms. The main reason for screening failure was an HbA1c value outside of the defined protocol range at the screening visit. All 680 patients were exposed to study treatment and included in the mITT population. In all, 65 patients (9.6%) prematurely discontinued study treatment during the 24-week main treatment period (8.6, 12.2, and 7.1% for lixisenatide morning, evening, and placebo, respectively). The main reason for treatment discontinuation was AEs (4.7 and 5.1% in the lixisenatide morning and evening groups, respectively, vs. 1.2% for combined placebo) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

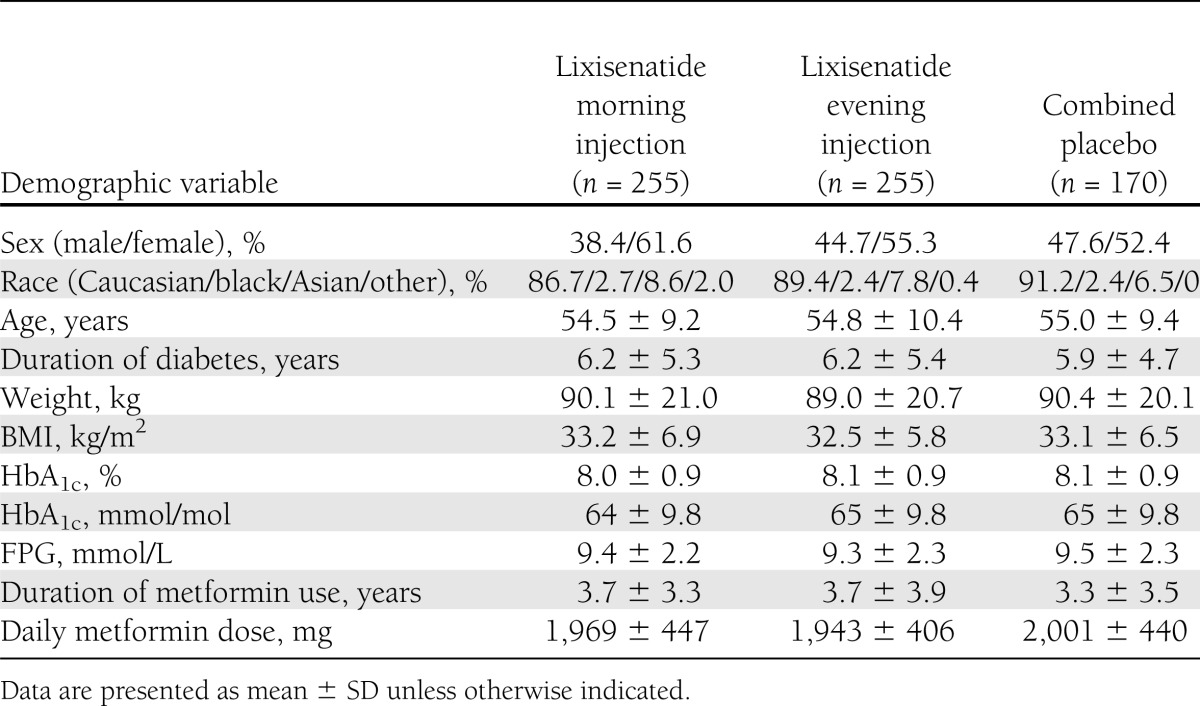

Demographic and baseline characteristics were generally similar across treatment arms, with the exception of a slight imbalance in sex (Table 1). The average treatment exposure was similar across treatment groups: 550 days (78.6 weeks) for combined placebo, 544 days (77.7 weeks) for lixisenatide morning, and 516 days (73.7 weeks) for lixisenatide evening injection arms. At the end of the 24-week main treatment period, the proportion of patients who were at the target daily dose of 20 μg was 92.2% in both the morning and evening injection lixisenatide groups and 97.1% in the placebo group.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics (safety population)

Efficacy

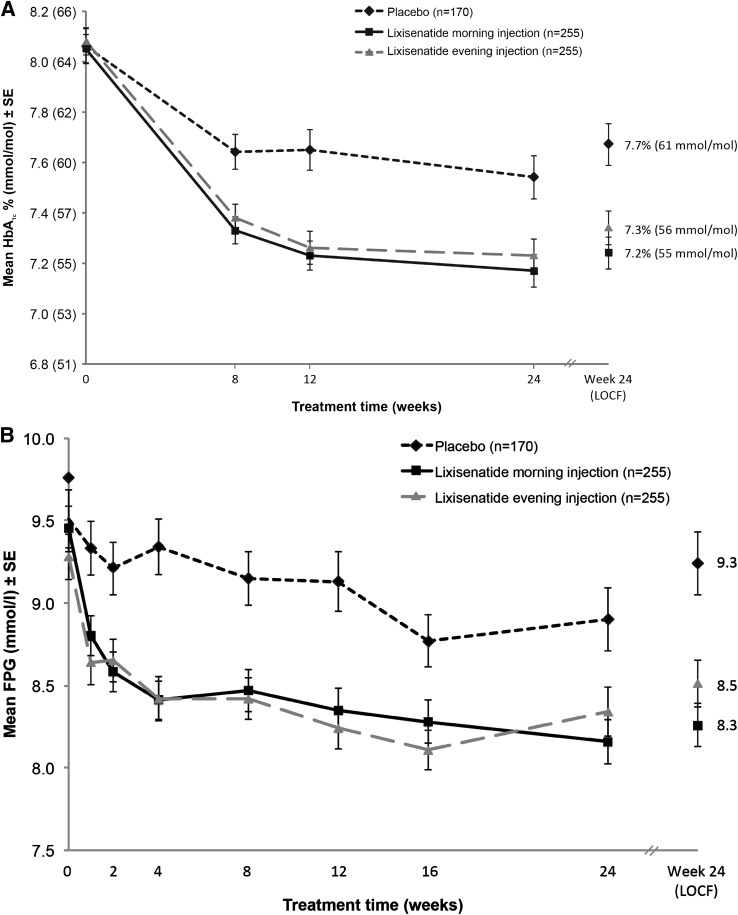

Lixisenatide morning injection significantly reduced mean HbA1c versus placebo: least squares (LS) mean change (±SE) from baseline to week 24, −0.9% (±0.07) (9.8 mmol/mol [±0.8]) for lixisenatide versus −0.4% (±0.08) (4.4 mmol/mol [±0.9]) for combined placebo. Mean HbA1c was also significantly reduced versus placebo for lixisenatide evening injection: LS mean change from baseline to week 24, −0.8% (±0.07) (8.7 mmol/mol [±0.8]) versus −0.4% (±0.08) (4.4 mmol/mol [±0.9]) for combined placebo. LS mean differences (±SE) versus combined placebo were as follows: morning injection, −0.5% (±0.09) (95% CI −0.66 to −0.31) (5.5 mmol/mol [±1.0] [95% CI –7.2 to –3.4]), P < 0.0001; evening injection, −0.4% (±0.09) (−0.54 to −0.19) (4.4 mmol/mol [±1.0] [–5.9 to –2.1]), P < 0.0001 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Mean HbA1c (A) and mean FPG (B) over 24 weeks with lixisenatide morning once-daily regimen, lixisenatide evening once-daily regimen, and placebo. Data are mean (±SE) as observed for the mITT population. For HbA1c, LS mean change difference vs. placebo at week 24, P < 0.0001 (morning and evening). For FPG, LS mean change difference vs. placebo at week 24, P < 0.0001 (morning) and P = 0.0046 (evening). LOCF, last observation carried forward.

The proportion of patients achieving HbA1c targets of <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (≤48 mmol/mol) at week 24 was significantly greater for lixisenatide morning and evening injection groups versus combined placebo. For lixisenatide morning injection, 43% of patients achieved an HbA1c <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) versus 22% for placebo (P < 0.0001), and 23.8% achieved an HbA1c ≤6.5% (≤48 mmol/mol) versus 10.4% for placebo (P = 0.0003). For lixisenatide evening injection, 40.6% achieved an HbA1c <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) versus 22% for placebo (P < 0.0001), and 19.2% achieved an HbA1c ≤6.5% (≤48 mmol/mol) versus 10.4% for placebo (P = 0.012).

Both lixisenatide treatment groups produced a significant reduction in FPG versus placebo from baseline to week 24. LS mean change (±SE) in FPG was −1.2 (±0.15), −0.8 (±0.15), and −0.3 (±0.17) for lixisenatide morning, lixisenatide evening, and combined placebo, respectively. LS mean difference (±SE) versus placebo was as follows: morning, –0.9 mmol/L (±0.2) (95% CI −1.33 to −0.56), P < 0.0001; evening, −0.6 mmol/L (±0.2) (−0.94 to −0.17), P = 0.0046 (Fig. 1B).

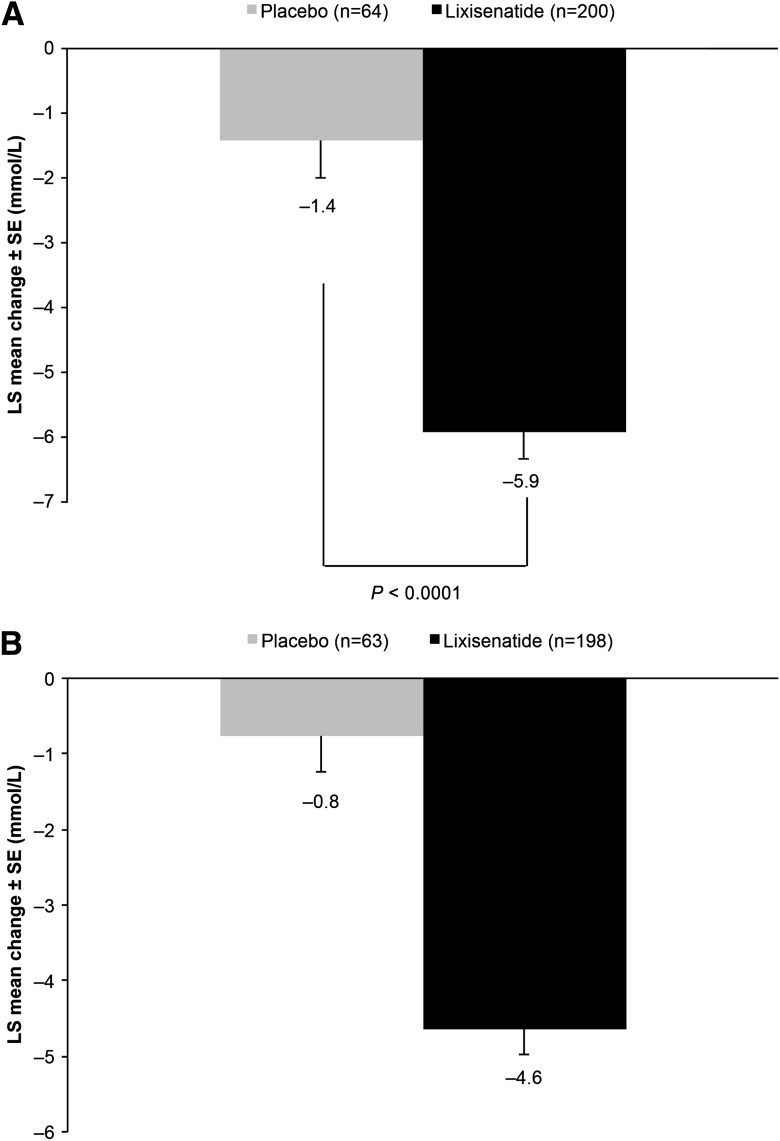

The breakfast meal test (performed only in the morning injection arms) revealed a significant reduction from baseline in 2-h PPG for lixisenatide morning injection compared with placebo morning injection at week 24. LS mean change (±SE) in PPG from baseline was −5.9 mmol/L (±0.42) for lixisenatide and −1.4 mmol/L (±0.59) for placebo. LS mean difference (±SE) versus placebo was −4.5 mmol/L (±0.58) (95% CI −5.65 to −3.37), P < 0.0001 (Fig. 2A). Treatment with lixisenatide also substantially decreased the glucose excursion (calculated as 2-h PPG, plasma glucose 30 min prior to the meal before study drug administration) after a standardized meal from baseline to week 24 compared with the morning placebo group LS mean change (±SE) from baseline: –4.6 mmol/L (±0.34) for lixisenatide and −0.8 mmol/L (±0.48) for placebo. LS mean difference (±SE) versus placebo was −3.9 (±0.48) (−4.82 to −2.94) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

LS mean change in postprandial glucose (A) and glucose excursion (B) from baseline to week 24 (last observation carried forward [LOCF]) with lixisenatide morning and placebo morning once-daily regimens. Data are mean values for the mITT population. Error bars represent the standard error. Glucose excursion calculated as 2-h PPG minus plasma glucose 30 min prior to the meal before study drug administration.

A significant improvement in β-cell function assessed by HOMA-B was observed in both lixisenatide arms versus placebo. LS mean change (±SE) from baseline was 8.0 (±2.45), 4.8 (±2.49), and −4.2 (±2.82) for lixisenatide morning, lixisenatide evening, and combined placebo, respectively. LS mean difference (±SE) versus placebo was as follows: lixisenatide morning, 12.1 (±3.28) (95% CI 5.69–18.56), P = 0.0002; lixisenatide evening, 9.0 (±3.32), (2.45–15.48), P = 0.0071 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Reduction in body weight from baseline to week 24 was similar in the morning and evening lixisenatide groups: LS mean change (±SE), −2.0 kg (±0.23) and −2.0 kg (±0.24), respectively, versus −1.6 kg (0.27) for combined placebo. These differences were not statistically significant. Both lixisenatide arms had significantly lower rates of patients requiring rescue medication versus combined placebo: morning injection, 2.7% (P = 0.0007); evening injection, 3.9% (P = 0.0063); placebo, 10.6%.

The number of patients who were antibody positive in the lixisenatide group increased with time, to a maximum at week 24 of 275 patients (73.1%; 155 patients [74%] in the morning and 120 [72%] in the evening groups). The concentration of antibodies was generally low and, overall, ∼70.0% of the patients were either assessed as antibody negative or had an antibody concentration below the lower limit of quantification (3.21 nmol/L). At week 24, changes in HbA1c were comparable in antibody-positive and -negative patients (LS mean change in HbA1c –0.9% [–9.8 mmol/mol] in antibody-positive patients and –1.0% [–10.9 mmol/mol] in antibody-negative patients in the morning group, and –0.8% [–8.7 mmol/mol] in antibody-positive and -negative patients in the evening group).

Safety and tolerability

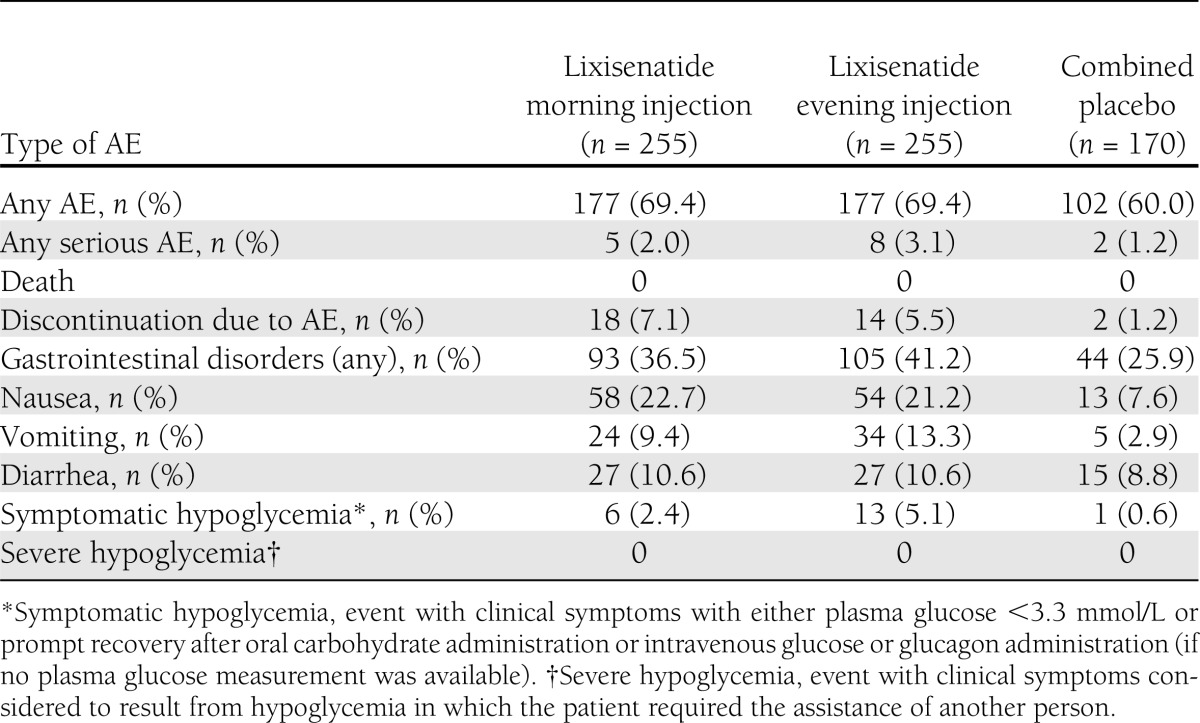

The overall incidences of AEs, serious AEs, and AEs leading to discontinuation were similar between the lixisenatide evening and morning injection regimens (Table 2). The most frequent treatment-emergent AE was nausea, which, in general, was reported more frequently during the first 5–6 weeks of treatment in both lixisenatide groups and during the first 4–5 weeks of treatment in the combined placebo group. The occurrence of any event of nausea decreased from week 5 to 6 to the end of treatment in all groups. All but three nausea events in three patients (two events in the lixisenatide evening injection group and one event in the combined placebo group) were mild to moderate in intensity, and the majority of events recovered without the need to administer corrective treatment. No patient had a serious treatment-emergent AE of nausea.

Table 2.

Adverse events

Six patients (2.4%) in the lixisenatide morning injection arm and 13 (5.1%) in the lixisenatide evening injection arm had symptomatic hypoglycemia events compared with 1 (0.6%) placebo-treated patient during the 24-week treatment period. In the lixisenatide morning injection arm, five of the reported eight hypoglycemia events occurred between 6:00 and 10:00 a.m. In the lixisenatide evening injection arm, 20 of the 23 hypoglycemia events occurred between 6:00 and 11:00 p.m. No specific pattern was observed in the onset of symptomatic hypoglycemia by weekly intervals. None of the symptomatic hypoglycemia events were severe in intensity. One patient (0.4%) in the lixisenatide morning injection arm and three patients (1.2%) in the lixisenatide evening injection arm discontinued study therapy owing to a treatment-emergent AE of hypoglycemia during the 24-week treatment period; no patients discontinued due to hypoglycemia in the placebo groups.

Three events were adjudicated as allergic reactions possibly related to investigational product by the ARAC. Two events occurred in the same morning lixisenatide injection patient and involved maculopapular rash and angioedema, which became serious and were resolved after permanent treatment discontinuation and corrective treatment. Moderate allergic dermatitis occurred in one patient in the evening injection lixisenatide group. These events led to permanent treatment discontinuation in both patients. Two additional patients had reported nonserious allergic treatment-emergent AEs that led to permanent discontinuation of study treatment, but the events were not adjudicated as allergic reactions by the ARAC.

Injection site reactions, which were mostly mild and transient, were reported for 6.7% of patients in each lixisenatide group and 3.5% of patients in the placebo group. There were no confirmed cases of pancreatitis or thyroid malignancy reported during the 24-week treatment period. Overall, there was no substantial difference in the AE profile between the antibody-positive and antibody-negative patients.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of this study have shown that lixisenatide given once daily as an add-on to metformin significantly improves glycemic control after 24 weeks of treatment, irrespective of whether it is administered before the morning or evening meal. From a baseline HbA1c of ∼8.1% (65 mmol/mol), lixisenatide led to a decrease of –0.9% (–9.8 mmol/mol) (morning injection) and –0.8% (–8.7 mmol/mol) (evening injection) versus –0.4% (–4.4 mmol/mol) with placebo (primary end point) at 24 weeks. Approximately 40% of patients who received lixisenatide morning or evening injection achieved an HbA1c <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) compared with ∼20% of those who received placebo.

The HbA1c reductions reported for lixisenatide in this study are largely consistent with those seen in studies with other GLP-1 receptor agonists added to metformin monotherapy, even if an unexpectedly large placebo effect induced a smaller placebo-subtracted difference. In a 30-week study, twice-daily exenatide was shown to reduce HbA1c by 0.8% (8.2–7.4%; 8.7 mmol/mol [66 to 57 mmol/mol]) using the highest dose of 10 µg twice daily (10). Studies with once-daily liraglutide (1.2–1.8 mg) have achieved HbA1c reductions of up to 1.5% (16.4 mmol/mol) (8.4–7.2% [68 to 55 mmol/mol] with 1.2 mg liraglutide; 8.4–6.9% [68 to 52 mmol/mol] with 1.8 mg liraglutide) in this setting over 26 weeks, albeit from slightly higher baseline HbA1c levels (11,12). The HbA1c reductions in the current study are also very similar to preliminary reports from other phase III studies involving add-on lixisenatide (once-daily prebreakfast) in patients insufficiently controlled on metformin monotherapy (13,14). In particular, in patients uncontrolled on metformin, add-on treatment with lixisenatide once daily was shown to be noninferior to exenatide twice daily at reducing HbA1c over 24 weeks (14).

Both lixisenatide arms demonstrated a statistically significant reduction from baseline to week 24 in FPG compared with placebo. Treatment with lixisenatide also provided a marked improvement in postprandial glycemic control, as shown by the ∼6 mmol/L decrease in 2-h PPG and 5 mmol/L decrease in glucose excursion in the morning injection arm. This marked improvement in PPG appears to be a highly consistent finding in studies with lixisenatide to date, including when used as a monotherapy (6,7,15–18). The pronounced effect of once-daily lixisenatide on PPG when used in combination with agents that primarily target fasting glucose (e.g., basal insulins) may provide useful clinical benefits (19–21).

The improvements in glycemic control reported here were accompanied by a significant improvement in β-cell function based on HOMA-B, which is consistent with preclinical mechanistic findings with lixisenatide and other GLP-1 receptor agonists (8). Insulinotropic effects are believed to contribute, alongside glucagonostatic effects, to the ability of GLP-1 receptor agonists to reduce endogenous glucose production (22–24). Postprandial glucose-lowering effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists, on the other hand, appear to be mediated mainly via slowing of gastric emptying, an effect that may be more prominent in shorter-acting agents, which may induce less tachyphylaxis (22–25).

Mean body weight decreased by ∼2 kg in the lixisenatide treatment arms at week 24, which can be considered as clinically relevant and beneficial for patients, and is in the same range as what is usually observed with other GLP-1 receptor agonists (26). Nevertheless, the difference compared with placebo was not significant. An analysis of the data did not reveal a reason for the body weight reduction observed in the placebo group; it was not related to specific investigational sites or countries or to specific baseline characteristics.

Furthermore, lixisenatide was well tolerated with a predictable AE profile consistent with previous studies of lixisenatide as well as other GLP-1 receptor agonists (13–17,27). As expected for a GLP-1 receptor agonist, mild and transient nausea and vomiting were the most commonly reported and only notable treatment-emergent AEs. Hypoglycemia frequency was slightly higher in the lixisenatide groups versus placebo but remained low with no cases of severe hypoglycemia. One of the key finds of the current study is that, in addition to the significant improvement in glycemic control provided by both the morning and evening administration of lixisenatide, the two regimens were comparable in terms of tolerability. Furthermore, the presence of antilixisenatide antibodies did not have any impact on the efficacy, safety, or tolerability of treatment.

Preliminary and published data from other studies with lixisenatide suggest that it is an effective, well-tolerated therapy when administered once daily before breakfast as either monotherapy or as an add-on to oral agents (e.g., metformin and/or sulfonylureas) or insulin-based treatment regimens (6,7,9,13,15,16), and is noninferior to twice-daily exenatide as an add-on to metformin (14). The results of the current study further demonstrate that administration of lixisenatide once daily before the evening meal can also provides an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for patients insufficiently controlled on metformin monotherapy. The option to choose either morning or evening administration increases flexibility of lixisenatide dosing to suit individual patient lifestyles. It has been suggested that hyperglycemia associated with the morning meal represents an early defect that can be resistant to oral glucose-lowering therapies (28), which would make it a particularly relevant target. However, for patients who typically have a large evening meal, evening dosing may be a more appropriate option. The GLP-1 receptor agonist liraglutide is also administered once daily and can be dosed at any time; however, it appears to be less effective than exenatide and lixisenatide at controlling postprandial glycemia and exerts its effects on HbA1c via more pronounced effects on FPG (17,27).

In this study, the reduction in body weight was –2.0 kg with lixisenatide compared with –1.6 kg in the placebo group. The placebo-subtracted difference was inferior to that observed in other studies in the GetGoal program (14,15). The reason for this effect is not known and not related to specific patient populations or countries, as suggested from subgroup analyses. The study also has the limitation that it was not planned to perform a daily glucose profile in these patients insufficiently controlled on metformin, and we cannot therefore conclude to what extent the effect of lixisenatide declines after morning or evening injections. Finally, it was not planned to compare the efficacy of morning versus evening injections of lixisenatide but only to compare each regimen with placebo. Therefore, no direct comparisons between morning and evening lixisenatide administration can be drawn from these data, as the study was not powered to detect differences between these two groups. A further limitation of this study was that the effect of lixisenatide on evening meal PPG using a standardized meal test was not conducted. Although this was not investigated, we hypothesize that improvements similar to those observed at the breakfast meal with morning lixisenatide administration would have been seen. It should also be noted that there is evidence from early studies with prebreakfast lixisenatide that PPG control can extend beyond the morning meal to subsequent meals, although with diminishing effect (18).

In conclusion, in patients with type 2 diabetes uncontrolled on metformin, add-on treatment with lixisenatide once daily, given in a morning or evening dosing regimen, significantly improved glycemic control over 24 weeks and was well tolerated. Lixisenatide improves both fasting and prandial glycemia with a pronounced prandial effect. The results suggest that either morning or evening administration of lixisenatide once daily can provide an effective treatment option with similar levels of tolerability in this setting, thus providing patients with the flexibility to suit their lifestyle.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by Sanofi, the manufacturer of lixisenatide. B.A. has consulted for Novartis A/S, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bristol-Myers Squibb/AstraZeneca and has received lecture fees from Novartis A/S and GlaxoSmithKline. R.A. has received research support and/or consulting honoraria from Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, and Takeda. P.M. and S.S. are employees of Sanofi. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

The investigators and representatives from Sanofi were responsible for the study design, protocol, conduct, statistical analysis plans, analysis, and reporting of the results.

B.A. researched the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and contributed to the discussion of the data. A.L.D. and R.A. were involved in the clinical conduct of the study and preparation of the manuscript. P.M. and S.S. designed and wrote the protocol, performed setup and medical supervision of the study, and reviewed manuscript data. Final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication was made jointly by all authors. B.A. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

These data were submitted in abstract form and accepted for oral presentation at the World Diabetes Congress of the International Diabetes Federation, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 4–8 September 2011.

The authors thank all of the investigators, coordinators, and patients who took part in this study. The authors also thank Huw Jones (Medicus International, London, U.K.) for providing editorial assistance, which was funded by Sanofi.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT00712673, clinicaltrials.gov.

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/dc12-2006/-/DC1.

References

- 1.Aroda VR, Ratner R. The safety and tolerability of GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2011;27:528–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell RK. Clarifying the role of incretin-based therapies in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther 2011;33:511–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christensen M, Knop FK. Once-weekly GLP-1 agonists: how do they differ from exenatide and liraglutide? Curr Diab Rep 2010;10:124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madsbad S. Exenatide and liraglutide: different approaches to develop GLP-1 receptor agonists (incretin mimetics)—preclinical and clinical results. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;23:463–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madsbad S, Kielgast U, Asmar M, Deacon CF, Torekov SS, Holst JJ. An overview of once-weekly glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists—available efficacy and safety data and perspectives for the future. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011;13:394–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonseca VA, Alvarado-Ruiz R, Raccah D, Boka G, Miossec P, Gerich JE, EFC6018 GetGoal-Mono Study Investigators Efficacy and safety of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in monotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes (GetGoal-Mono). Diabetes Care 2012;35:1225–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ratner RE, Rosenstock J, Boka G, DRI6012 Study Investigators Dose-dependent effects of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabet Med 2010;27:1024–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner U, Haschke G, Herling AW, Kramer W. Pharmacological profile of lixisenatide: a new GLP-1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept 2010;164:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen M, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T, Holst JJ. Lixisenatide for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2011;20:549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005;28:1092–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. LEAD-2 Study Group Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care 2009;32:84–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratley RE, Nauck M, Bailey T, et al. 1860-LIRA-DPP-4 Study Group Liraglutide versus sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have adequate glycaemic control with metformin: a 26-week, randomised, parallel-group, open-label trial. Lancet 2010;375:1447–1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolli G, Munteanu M, Dotsenko S, et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once-daily versus placebo in patients with T2DM insufficiently controlled on metformin (GetGoal-F1) (Abstract). Diabetologia 2011;54(Suppl. 1):A784

- 14.Rosenstock J, Raccah D, Koranyi L, et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily versus exenatide twice daily in patients with T2DM insufficiently controlled on metformin (GetGoal-X) (Abstract). Diabetologia 2011;54(Suppl. 1):A786

- 15.Ratner R, Hanefeld M, Shamanna P, et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily versus placebo in patients with T2DM insufficiently controlled on sulfonylurea ± metformin (GetGoal-S) (Abstract). Diabetologia 2011;54(Suppl. 1):A785

- 16.Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A, EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab 2012;14:910–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kapitza C, Forst T, Coester HC, Poitiers F, Ruus P, Hincelin-Méry A. Pharmacodynamic characteristics of lixisenatide once daily vs liraglutide once daily in patients with T2DM inadequately controlled with metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 25 February 2013 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett AH. Lixisenatide: evidence for its potential use in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Core Evid 2011;6:67–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg SK. The role of basal insulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists in the therapeutic management of type 2 diabetes—a comprehensive review. Diabetes Technol Ther 2010;12:11–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perfetti R. Combining basal insulin analogs with glucagon-like peptide-1 mimetics. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011;13:873–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenstock J, Fonseca V. Missing the point: substituting exenatide for nonoptimized insulin: going from bad to worse! Diabetes Care 2007;30:2972–2973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cervera A, Wajcberg E, Sriwijitkamol A, et al. Mechanism of action of exenatide to reduce postprandial hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008;294:E846–E852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linnebjerg H, Park S, Kothare PA, et al. Effect of exenatide on gastric emptying and relationship to postprandial glycemia in type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept 2008;151:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cersosimo E, Gastaldelli A, Cervera A, et al. Effect of exenatide on splanchnic and peripheral glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetic subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1763–1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nauck MA, Kemmeries G, Holst JJ, Meier JJ. Rapid tachyphylaxis of the glucagon-like peptide 1-induced deceleration of gastric emptying in humans. Diabetes 2011;60:1561–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vilsbøll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, Knop FK, Gluud LL. Effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012;344:d7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. LEAD-6 Study Group Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet 2009;374:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monnier L, Colette C, Rabasa-Lhoret R, et al. Morning hyperglycemic excursions: a constant failure in the metabolic control of non-insulin-using patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]