Abstract

Self-stigma can undermine self-esteem and self-efficacy of people with serious mental illness. Coming out may be one way of handling self-stigma and it was expected that coming out would mediate the effects of self-stigma on quality of life. This study compares coming out to other approaches of controlling self-stigma. Eighty-five people with serious mental illness completed measures of coming out (called the Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale, COMIS), self-stigma, quality of life, and strategies for managing self-stigma. An exploratory factor analysis of the COMIS uncovered two constructs: benefits of being out (BBO) and reasons for staying in. A mediational analysis showed BBO diminished self-stigma effects on quality of life. A factor analysis of measures of managing self-stigma yielded three factors. Benefits of being out was associated with two of these: affirming strategies and becoming aloof, not with strategies of shame. Implications for how coming out enhances the person’s quality of life are discussed.

Stigma has a significant and harmful impact on people with serious mental illness, interfering with important goals related to work, independent living, health, and wellness. The distinction between public and self-stigma is one way in which the overall concept of stigma has been described (Corrigan, 2005; Hinshaw, 2007; Thornicroft, 2006). Public stigma is the prejudice and discrimination that emerges when the general population endorses specific stereotypes; e.g., all people with mental illnesses are incompetent and incapable of maintaining a real job. Self-stigma, the focus of this article, represents the impact of internalizing stigma (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). People who agree with and apply the stereotypes of mental illness to themselves suffer broad consequences including diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy (Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006; Link, 1987; Link, Cullen, Frank, & Wozniak, 1987; Markowitz, 1998; Ritsher, Otilingam, & Grajales, 2003; Ritsher & Phelan, 2004; Rosenfield, 1997; Rüsch, Hölzer, et al., 2006a,b). Self-stigma’s effect in the work world, for example, leads to decreases in self-esteem (“I am not worthy to work in such a good place”) and diminutions in self-efficacy (“I am unable to carry out such jobs”).

In this study, we chose to look at two proxies of self-stigma recognizing that self-stigma is a complex construct and may be framed in alternative ways. First, we measured the level of stigma people with mental illness perceive in society. Although perceived stigma by no means captures the entire process of self-stigma, it does represent the initial step of this process and a major source of self-stigma (Corrigan & Watson, 2002; Corrigan et al., 2006). We therefore consider it a proxy of self-stigma, reflecting the threat of being stigmatized, which is then often internalized. As a second self-stigma proxy, we measured the opposite of self-stigma, empowerment (Corrigan, Faber, Rashid, & Leary, 1999); namely, people who are high in personal empowerment are low in self-stigma. In terms of outcomes affected by self-stigma, we opted to view the impact of self-stigma broadly and used an omnibus measure of quality of life to do so.

Large-scale efforts have been mobilized in the past decade to challenge public stigma including America’s Erase the Barriers Initiative, Beyond Blue in Australia, and very new programs in Canada and the United Kingdom. These approaches do not readily transfer to the challenges of self-stigma. One reason is the experience of mental illness and related treatment is largely hidden (Goffman, 1963). Race and gender are prototypes of stigma with readily manifest qualities; e.g., people with dark skin are African. Contrast this to the person in a group without such obvious marks that indicate whether an individual belongs to that stigmatized group (Goffman, 1963). For example, gay men and lesbians are not recognized by others unless they somehow choose to identify themselves as such. Similarly, most people with serious mental illness are not obvious unless they discuss their illness or mental health history.

This kind of hidden identity may protect the person opting to remain in the closet, i.e., deciding not to let others know of one’s mental health history. People who come out about their mental illnesses may expose themselves to additional discrimination and social disapproval. Research suggests however, that people who are out about their condition often report benefits (Pachankis, 2007). Studies on the gay community, for example, identified benefits including less stress from having to no longer keep the secret (Rosario, Hunter, Maguen, Gwadz, & Smith, 2001). These benefits are also associated with better relationships with one’s partner (Beals & Peplau, 2001) and improved job satisfaction (Day & Schoenrade, 1997, 2000). People who come out about their sexual orientation report greater support from their families (Kadushin, 2000).

Gays and people with serious mental illnesses share important characteristics which suggest coming out in terms of sexual orientation yields a useful framework for the goals of this study (Corrigan & Matthews, 2003). Characteristics include being the victim of a hidden stigma for a condition that often appears in adolescence or early adulthood to a person living in a family with parents and siblings absent the condition. We are not equating sexual orientation with mental illness; we only utilize the sexual orientation coming-out process as a model for exploring mental illness disclosure. In this article, we test the hypothesis that coming out is a mediator that reduces the association between self-stigma and quality of life. Namely, people who are more out about their mental illness are less likely to experience the egregious effects of self-stigma on quality of life.

In many ways, coming out may be framed as a strategy that challenges self-stigma. Researchers have identified other approaches to managing self-stigma (Link, 1987; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007), which could be divided into approaches meant to hide the stigmatizing condition (e.g., secrecy, shame, and withdrawal) versus those that affirm the person despite the stigma (educating the public or challenging stigmatizers). We hypothesize that these two factors of self-stigma change would emerge in exploratory factor analyses and expect to show benefits of coming out are associated with the more affirming approaches that emerge from the factor analysis.

METHOD

People with serious mental illnesses were recruited from two community-based rehabilitation programs in the Chicago area. Mental illnesses were defined as serious for people who were unable to maintain work or live independently because of a psychiatric disorder. Eighty-five people were fully informed of the study, agreed to participate, and satisfactorily completed test instruments; no one refused because people sought out the research team (by phone or in person) after reading a flyer or being informed about the study by staff. The institutional review boards at the Illinois Institute of Technology and collaborating organizations approved the study before recruitment began. The sample is described in Table 1. The group was 44.8 years of age on average and more than two thirds of the group were men. About the sample was African American and a third were European American. Approximately two thirds of the group had attended college and had never married. Income was below $ 20,000 for 95.3% of the participants. At the time of the study, 2.4% of the sample was working fulltime, 15.3% was employed part-time.

Table 1.

Demographics and Other Illness-Related Variables (n = 85)

| Variable | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age | M = 44.8, SD = 9.7 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Female | 31.8 |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| African American | 57.6 |

| European American | 34.1 |

| Hispanic | 4.7 |

| Other | 3.5 |

| Education (%) | |

| High school diploma or less | 35.3 |

| Some college or more | 64.7 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Single | 68.2 |

| Married, separated/divorced, widowed | 31.8 |

| Life-time psychotic disorder (% yes) | 52.9 |

| Times hospitalized | M = 9.24, SD = 13.05 |

| Current use of antipsychotic medication (% yes) | 71.8 |

Information was also collected about the person’s experience with mental illness and summarized in Table 1. Research participants showed many of the experiences characteristic of serious mental illness. About half the sample had a lifetime history of psychosis as assessed by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1998) based on criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and was, on average, hospitalized about nine times. About 70% of research participants were prescribed antipsychotic medication at the time of the study. All mental health history was provided by the person with mental illness.

Measures

In addition to demographics and diagnostics, we used data from five instruments that were part of the battery from a larger study on implicit and explicit models of stigma and mental illness (Rüsch, Corrigan, Powell, et al., 2009c,d; Rüsch, Corrigan, Todd, & Bodenhausen, 2010a; Rüsch, Corrigan, Wassel, et al., 2009; Rüsch, Todd, Bodenhausen, et al., 2009e; Rüsch, Todd, Bodenhausen, & Corrigan, 2010b; Rüsch, Todd, Bodenhausen, Olschewski, & Corrigan, 2010c; Rüsch et al., 2009a,b).We administered two tests we thought to be proxies of self-stigma. Link’s (1987) 12-item Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Questionnaire (PDDQ) was used to measure the perceived level of stigma; scores on this test reflect how participants recognize stigmatizing stereotypes. Higher scores meant more perceived stigma (Cronbach’s a for our sample = .85). We have argued elsewhere that self-stigma and personal empowerment define opposite ends of a continuum (Corrigan et al., 1999). People who believe they have power over life decisions and mental health services are less likely to perceive and internalize stigma. Hence, we used the Empowerment Scale as an index of personal empowerment (Rogers, Chamberlin, Ellison, & Crean, 1997). Items for the scale were originally identified by a panel of 10 leaders in the consumer movement and then validated by participants in six self-help programs. A sample item is “I can pretty much determine what will happen in my life” to which participants responded using a 4-point agreement scale (4 = strongly agree). Internal consistency for data from our study was good (Cronbach’s α = .82). All items were summed to yield an overall empowerment score.

The Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale (COMIS)

An instrument assessing coming out for people with serious mental illness could not be found in the literature at the time of this study. Earlier, we proffered the gay community among those with hidden identities who struggle with coming out. Their community has had at least partial success in using coming out to address personal as well as public hurdles related to sexual orientation. For this reason, we completed extensive interviews with gay men and lesbians on staying in the closet and coming out (Corrigan et al., 2009). Interviews of these individuals enhance the content validity of the measure. Sorting and coding interview transcripts were reliable (ICC.93) and yielded 30 distinct themes that were categorized into 13 conceptual frameworks. In further attempting to make sense of these findings, we observed that one conceptual framework represented consideration of the cost–benefits separately for perceptions about coming out versus those related to staying in the closet. These earlier findings consistently showed disparate responses to questions about coming out versus those about staying in the closet.

We then developed the Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale (COMIS, see the Appendix) comprising 21 items, 7 representing benefits about coming out of the closet (“I came out of the closet to be true to myself ”) and 14 items about benefits to remaining in the closet (“I stayed in the closet to avoid public shame”). Each of these items was reviewed by two independent experts regarding their relevance with the coming out experience for people with mental illness; items were edited or omitted in cases where those representing the gay and lesbian perspective did not parallel that of people with serious mental illness. Participants responded to each item with a 7-point agreement scale (7 = strongly agree).

A second observation from the gay and lesbian interviews was that the meaning of coming out varied when examined in terms of current status, whether interviewees discussed currently “being out” or currently “staying in.” Pros and cons to coming out have a completely different meaning when the person is actually out at the time of the interview. Hence, the COMIS begins with a single yes or no question: “Are you out about your mental illness? In other words, have you decided to tell most of your family, friends, and acquaintances that you have a mental illness? Have you decided not to hide it?” Those who answered “yes” were administered items phrased about why the person is currently out and why he or she was in the closet in the past. Those responding “no” were given items about why they prefer to stay in the closet and why they might come out in the future.

Other stigma-management strategies

An additional goal of this study was to determine how coming out compared to other approaches a person might select to manage stigma. We therefore used Link’s revised Stigma Coping Orientation Scales (SCOS; Link, Struening, Neese-Todd, Asmussen, & Phelan, 2002) to measure five coping styles with corresponding internal consistencies of data from the participants of our study: secrecy (α = .92), withdrawal (α = .80), educating (.73), challenging (.77), and cognitive distancing (.78). These were included as proxies of some ways in which people with mental illness might address stigma. Each of these scales is defined in Table 3, for part of a hierarchical factor analysis of antistigma management scales. We included two factors from Tangney’s Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA-3; Rüsch et al., 2007; Tangney, Dearing, Wagner, & Gramzow, 2000) that we believe parallels reactions to stigma. Hence, we framed TOSCA-3 responses as stigma management approaches: detaching and externalizing. The short version of the TOSCA-3 consists of 11 social scenarios; e.g., “You attend your coworker’s housewarming party and you spill red wine on a new cream-colored carpet, but you think no one notices.” For each scenario, possible reactions are presented with responses consistent with two stigma management styles: detached (e.g., “You think your coworker should have expected some accidents at such a big party”), and externalizing (“You would wonder why your coworker chose to serve red wine with the new light carpet”). Research participants respond to each possible reaction using 1 to 5 (very likely) scales. Eleven items are summed representing detachment (Cronbach’s α from our dat α = .70) and 11 items are added up for externalization (α = .75).

Table 3.

Principal Component Analysis of Types of Anti-Stigma Strategies Obtained From the Stigma Coping Orientation Scales (SCOS), Test of Self-Conscious Affect (TOSCA-3) and Group Identification Measure.

| Components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure subscale scores | Definitions | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

| Secrecy (SCOS) | Do not tell anyone | −.41 | −.15 | .75 |

| Withdrawal (SCOS) | Stay with own kind | .28 | .40 | .63 |

| Educating (SCOS) | Teach the public about mental illness | .91 | .04 | −.04 |

| Challenging (SCOS) | Tell others when they are stigmatizing | .83 | −.06 | .18 |

| Cognitive distancing (SCOS) | I am not like other people with mental illness. | .05 | .13 | .62 |

| TOSCA-3 Detached | That kind of situation is not important to me. | .05 | .87 | −.07 |

| TOSCA-3 Externalize | That is someone else’s fault, not mine. | .01 | .78 | .26 |

| Group identification | I recognize that I am like other people with mental illness. | .54 | .21 | −.35 |

| Factor description | Affirming strategies | Becoming aloof | Strategies of shame | |

| Eigenvalues | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.2 | |

| Percent of variance | 28.0% | 23.0% | 14.6% | |

Note. We used the entire sample (N = 85) to increase the power of these analyses.

Group identification is relevant to coping with perceived discrimination among members of stigmatized minority groups (Rüsch et al., 2009b). One might think that people with mental illnesses would escape stigma by dissociating with others with mental illnesses. Research has shown, however, that those who identify and otherwise associate with members of a stigmatized group seem to be empowered, which then diminishes self-stigma (Jetten, Branscombe, Schmitt, & Spears, 2001). Identification with the group of people with mental illnesses was measured by using five items adapted from Jetten and colleagues (see also Rüsch, Lieb, Bohus, & Corrigan, 2006). Consider as an example “I feel strong ties with the group of people with mental illnesses” to which research participants responded with a 7-point agreement scale (7 = completely agree). Cronbach’s alpha for these data was .85.

Impact of self-stigma and coming out

Consistent with our previous research (Corrigan et al., 1999), we used quality of life as an index of impact; it was assessed using the 17-item subjective component of Lehman’s (1988) Quality of Life Interview, used extensively in psychosocial research about people with serious mental illness. Higher scores indicate better quality of life (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Analysis

Analyses summarized in the Results section included descriptive and inferential statistics. First, we determined the frequency of research participants who were indeed out about their mental illness. Factor analyses were completed to make sense of what people with mental illness meant about coming out. Demographic differences across COMIS factors were completed next. The mediating effect of COMIS factor scores on the relationship between proxies of self-stigma and quality of life was tested using the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986). Finally, COMIS factors were considered as ways to manage self-stigma. Hence, we examined the relationships between COMIS factors and other strategies for managing self-stigma. All analyses were done using SPSS 16.0.

RESULTS

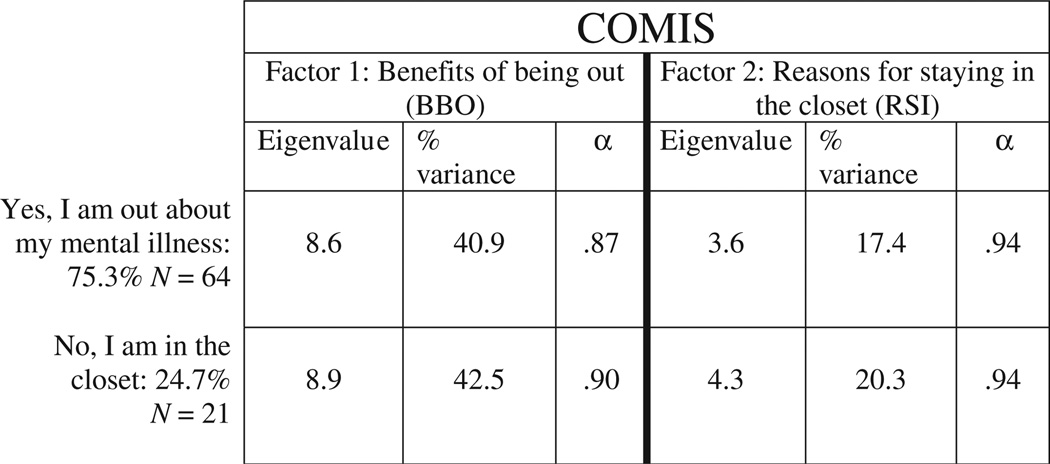

In this study, we defined coming out in two ways, which are summarized in Figure 1: (a) a categorical response to the yes/no question, “Are you out about your mental illness?” and (b) responses to Likert-style COMIS items that comprise one of two continuous factors: benefits of being out (BBO) and reasons for staying in (RSI). These factors are discussed below as the product of an exploratory factor analysis, which is also summarized in Figure 1. Results showed 75.3% (n = 64) of research participants reported that yes, they were out about their mental illnesses and had decided to tell family, friends, and acquaintances; the remaining 24.7% (n = 21) said they had opted not to come out at the time of this study. Analyses of variance completed across these two groups failed to yield significant differences for any of the demographics or for disorder-related variables (p<.20). This absence of findings seems to challenge whether this kind of coming out question has any conceptual merit. Categorical analyses like these have less power than using the COMIS factors, which provide continuous and hence more powerful assessments. Therefore, COMIS scores are the focus of the remainder of this article.

Figure 1.

The two Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale (COMIS) yes/no responses representing self-identification as being in or out of the closet (n = 85).

An exploratory, principal component analysis (PCA) was completed to test whether COMIS items actually corresponded with the two hypothesized factors: benefits of being out versus staying in the closet (see Fig. 1). This analysis was completed only for research participants who answered yes to the indexed question (n = 64). The PCA with varimax rotation yielded two factors with large eigenvalues (> 3.5), which accounted for 58.3% of the variance. The two factors were consistent with our hypotheses: benefits of currently being out of the closet (BBO) and reasons that I stayed in the closet in the past (RSI).We repeated the PCA on the much smaller sample of people, who said “No they were not out” (N = 24) and found similarly strong factors. We are conservative about drawing inferences from the sample given its small size. Remaining analyses (except for Table 3, see below) examined relationships of the two COMIS factors for the Yes group only (n = 64), because the sample size for the No group was too small for suitably powered analyses. In this group of 64 participants, BBO and RSI scores were correlated, but only mildly so (r= −.26, p<.05). Findings were further supported by Cronbach’s alphas for the factors ranging from .87 to .94. These findings support the reliability of COMIS factors.

Means and standard deviations for COMIS factors are broken out by demographics and stigma-related constructs in Table 2. One of our central questions in this study is how coming out mediates the impact of perceived discrimination or personal empowerment. Benefits of being out, the COMIS Factor 1, was significantly associated with quality of life while no such significant relationship was found with Factor 2, RSI. We examined correlations of the two indices of the self-stigma proxies, the PDDQ and total score from the Empowerment Scale, with the two COMIS factors. A significant relationship was found between BBO and the total Empowerment Scale score. Nonsignificant trends describe the relationship between perceived stigma and BBO. No significant relationships were found for COMIS Factor 2 and the two self-stigma indicators.

Table 2.

Correlations and Group Differences of COMIS Factors With Selected Demographics Plus Measures Of Impact, Self-Stigma, and Stigma Management Strategies (n = 64)

| Selected demographics | Factor 1: Current benefits of being out (BBO) |

Factor 2: Past reasons for staying in the closet (RSI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | r = .05 | r = .04 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | M = 4.33, SD = 1.53 | M = 3.92, SD = 1.73 |

| Female | M = 4.80, SD = 1.85 | M = 5.36, SD = .97 |

| F(1,60) = 1.12, ns | F(1,60) = 11.90, p<.001 | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American | M = 4.97, SD = 1.40 | M = 4.44, SD = 1.55 |

| European American | M = 3.54, SD = 1.62 | M = 4.21, SD = 1.90 |

| F(1,60) = 12.36, p<.005 | F(1,57) = .23, ns | |

| Education | ||

| ≤ High school | M = 4.53, SD = 1.62 | M = 4.00, SD = 1.78 |

| ≥ Some college | M = 4.44, SD = 1.69 | M = 4.60, SD = 1.58 |

| F(1,62) = .04, ns | F(1,62) = 1.87, ns | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | M = 4.61, SD = 1.55 | M = 4.46, SD = 1.66 |

| Married/separated/divorced | M = 4.16, SD = 1.85 | M = 4.24, SD = 1.71 |

| F(1,62) = 1.0, ns | F(1,62) = .24, ns | |

| Diagnoses | M = 4.86, SD = 1.57 | M = 4.08, SD = 1.55 |

| Psychosis (yes) | M = 3.96, SD = 1.64 | M = 4.79, SD = 1.75 |

| Psychosis (no) | F(1,62) = 4.96, p = .09 | F(1,62) = 2.81, p<.05 |

| Current Antipsychotics | ||

| Yes | M = 4.53, SD = 1.67 | M = 4.00, SD = 1.65 |

| No | M = 4.31, SD = 1.63 | M = 5.34, SD = 1.32 |

| F(1,62) = .23, ns | F(1,62) = 9.40, p<.005 | |

| Times hospitalized | r = .04 | r = −.00 |

| Times involuntarily hospitalized | r = −.01 | r = −.02 |

| Impact | ||

| Quality of life | r = .32** | r = −.10 |

| Self-stigma and empowerment | ||

| PDDQ: perceived stigma | r = −.21* | r = .21* |

| ES: total personal empowerment | r = .29** | R = −.15 |

Note. COMIS = Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale; PDDQ = Perceived Devaluation-Discrimination Questionnaire; ES = Empowerment Scale.

p<.10;

p<.05.

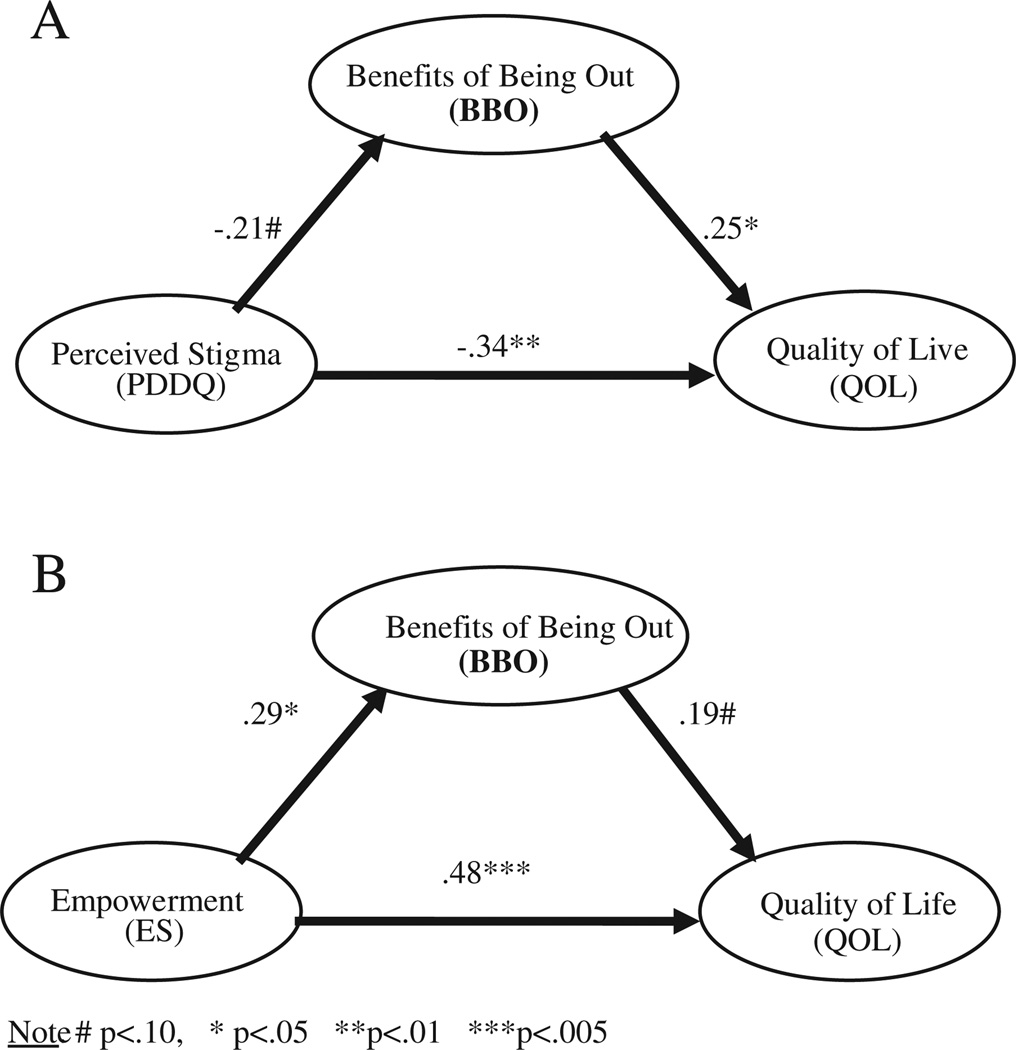

We then used Baron and Kenny’s (1986) framework to examine whether coming out does indeed mediate the effect of perceived stigma and empowerment scores on quality of life. This analysis was supplemented by the Sobel test on the indirect effect (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). We excluded RSI from these analyses because it was not found to be significantly related to quality of life or the two indices of self-stigma. Findings are provided separately for the effects of perceived stigma and overall empowerment in Figure 2. Four results are needed to support inferences about a mediating effect; consider them in terms of how coming out mediates the effects of perceived stigma on quality of life (Fig. 2A). (1) Perceived stigma is significantly associated with the dependent variable (quality of life: β = −.39, p<.005). (2) The independent variable (perceived stigma) has a significant effect on the mediator (BBO; a nonsignificant trend describes this relationship; β=−.21, p = .09). This yields a more conservative assertion about support for mediation. (3) Benefits of being out is significantly related with the Quality of Life Scale total score in the full model (β=.25, p<.05). (4) If these three premises are supported, then the relationship between perceived stigma and quality of life that emerges from the full model (the direct effect) must be smaller than the value found in the regression representing the total effect. Consistent with a mediated effect, the beta for perceived stigma effects on quality of life in the full model was smaller (−.34) than that representing the total effect of perceived stigma on quality of life (−.39). Another way to test for mediation is using the Sobel test, which focuses on the magnitude of the indirect effect, i.e., the part of the relationships between perceived stigma and quality of life that occurs through the mediator. The Sobel test is the product of the effect between perceived stigma and BBO with the effect between BBO and quality of life. The standardized indirect effect was significant although small (−.05), with a bootstrap confidence interval ranging from −.0002 to −.17. Thus, although the results of the Baron and Kenny (1986) steps were not entirely supportive, the test on the indirect effect confirmed the presence of mediation. Coming out acted as a partial mediator and accounted for about 14% of the total effect.

Figure 2.

Results of regression analyses testing for mediational effects (n = 64).

Figure 2B summarizes findings examining coming out as a mediator of the relationship between empowerment and quality of life. A significant relationship was found between Empowerment and Quality of Life Scales (β = .53, p<.001). Empowerment was also significantly related to BBO (beta = .29, p<.05). Benefits of being out was significantly correlated with quality of life (r = .32, p<.05); however, the relationship in the full model did not reach statistical significance (β = .19, p = .10). Once again, there was mixed support for this component of the model. Still, the direct effect of empowerment on quality of life from the full model (.48) was smaller than the total effect (.53). The standardized indirect effect was significant although small (.05), with a bootstrap confidence interval ranging from .0003 to .18. Overall, these results provide some support for coming out acting as a partial mediator, explaining 9% of the relationship between empowerment and quality of life.

Research participants also completed items representing disparate approaches to stigma from the Stigma Coping Orientation Scales and TOSCA-3, and a measure of group identification. Our goal was to determine how coming out relates to these approaches. Table 3 summarizes the results of an exploratory, principal component analysis of scales from these measures. A 3-factor solution emerges with eigenvalues above 1.2. We defined the factors as affirming strategies (approaches meant to address stigma and maintain a person’s self-esteem), becoming aloof (viewing stigma-eliciting situations as irrelevant), and strategies of shame (addressing self-stigma by hiding one’s disgrace). Becoming aloof and strategies of shame were found to correlate significantly (r = .22, p<.05). Affirming strategies were not significantly associated with the two other factors.

Multiple regression analyses were completed to determine the relationship between COMIS factors and the three factors representing antistigma strategies (see Table 4). RSI again failed to yield any significant associations with the three antistigma strategy factors. Benefits of being out was independently associated with affirming strategies and becoming aloof. Independent variables in the full model accounted for 30% of variance in the BBO factor.

Table 4.

Regression Analysis of COMIS Scales Predicted by Three Antistigma Strategies (n = 64)

| Independent variables | Factor 1: Current benefits of being out (BBO) β |

Factor 2: past reasons for staying in the closet (RSI) β |

|---|---|---|

| Affirming strategies | .39*** | −.05 |

| Becoming aloof | .31** | .10 |

| Strategies of shame | −.13 | .06 |

| R2 | .30 | .02 |

Note. COMIS5Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale.

p<.01;

p<.005.

DISCUSSION

We sought to make sense of the complex phenomenon called coming out by first distinguishing people who, at the time of the study, reported they were out about their mental illness and disclosed to others versus those who were not. Just about three out of four respondents in the study reported they were out to others about their mental illness; three times the number of research participants who said they had not disclosed their mental illness. This ratio partly reflects biases in study recruitment; people with mental illness who are comfortable with disclosing their mental illness are more likely to volunteer for this kind of study. Also note that the 85 research participants are not a representative sample of people with serious mental illness: there were more African Americans and having once married participants than other descriptions of people with mental illness (Manderscheid, Atay, & Crider, 2009). Still, although we are hesitant to apply the frequencies found in this study to understanding the population of people with these disorders, the results provide some interesting inferences about coming out.

Categorical findings about being out versus staying in groups were telling, but subsequent statistics for the most part failed to yield significant differences across most of the demographics, as well as the measures of quality of life, self-stigma, and empowerment. Stochastic failure of the yes/no response may have occurred because the actual experience is not categorical. Rather, coming out depends on who is involved and what is the information to be disclosed, better understood as a continuous variable. Our subsequent analyses uncovering two factors in the COMIS seemed to support this assertion. Benefits of being out represented the personally meaningful incentives for sharing one’s experience with mental illness. Reasons for staying in listed preferences why the person should not disclose. Statistically, BBO seemed to be a useful construct because it was found to be significantly associated with many of the other independent variables used in this study, thereby providing information about the importance of coming out. The RSI, however, was mostly not related to the demographics and other variables. This may seem counterintuitive, but can be explained by the nature of the task. Among those 64 participants who were “out,” current benefits of being out, but past reasons for staying in the closet were measured. Therefore, current benefits were, more than past reasons, likely to be associated with other current constructs of the study; research participants generate current insights (BBO) rather than past ideas, and current considerations better parallel the remaining measures in the study. One might expect the correlation coefficient for BBO and RSI to be significant and robust because they are different sides of the same construct. However, the correlation coefficient only equaled −0.26, a noticeably small relationship given the shared method variance in completing the COMIS. The finding suggests that reasons for staying in the closet in the past do not strongly predict the current benefits of being out.

Coming out is especially interesting in its putative effect as a mediator between self-stigma and quality of life. We examined this relationship twice, with two different proxies of self-stigma. Partial support was obtained for the mediating effect between perceived stigma and quality of life. The independent Sobel test supported mediational inferences, but the relationship between PDDQ and BBO was no more than a nonsignficant trend (β = −.21, p<10). Mediating effects on empowerment and quality of life were similar. The Sobel test was again significant as well as the betas except for the association between BBO and quality of life; this was a nonsignificant trend (r = .19, p<10). Combined, these findings suggest people who are out about their mental illness experience a less negative impact of self-stigma on quality of life. People who are out and report personal empowerment are going to be more satisfied with life.

One way we framed coming out is as a strategy for managing stigma. We sought to make sense of stigma management strategies by examining the factor structure of relevant variables from three other instruments. Three factors emerged from a corresponding exploratory factor analysis. Affirming strategies frame stigma as an unjust, outer force that should be directly dealt with by educating or otherwise addressing public attitudes. Consider Jill, for example, a person with bipolar disorder who sometimes questions her on-the-job competence because a coworker, Fred, disparages other, similar employees in their office saying they are “lazy mental types.” Jill could address this stigma by educating Fred that people with serious mental illness are often successful in the business world, especially when reasonable accommodations are provided. Some people may handle stigma by being aloof of the situation. They become detached from stigmatizing interactions, diminish the importance of these situations, and externalize self-stigma that may emerge. Jill might argue to herself that the job is not really important and that Fred is not too smart anyway.

The third factor suggests an approach that may actually maintain self-stigma, what we called strategies of shame. This factor suggests that the stigma of mental illness is in some ways valid and that the person should hide this mark. To do this, people withdraw from important interactions or otherwise keep one’s mental health experience private. Jill might quit her job to avoid hostile comments by Fred and others. Benefits of being out was found to be associated with affirming strategies and being aloof; no significant relationship was found between BBO and strategies of shame. This pattern suggests coming out may be mostly a positive and encouraging experience, one that frequently ends up facilitating a person’s goals instead of narrowing them.

Benefits of being out was found to vary with theoretically interesting demographics. Most notable was the BBO difference in ethnic groups. The African American participants were more likely to identify and endorse the benefits of being out than European Americans. We wondered whether an ethnicity effect moderated BBO’s impact on self-stigma and quality of life. Regression equations corresponding with the Baron and Kenny (1986) outline failed to support a conclusion about moderation. Still, these findings suggest African Americans saw more advantages in being out about their illness compared to Whites. There is mixed evidence on the link between ethnicity and stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness; some studies show that members of ethnic minorities endorsed stigma less strongly than Whites (Corrigan, Edwards, Green, Diwan, & Penn, 2001), others finding more prejudice toward people with mental illness in ethnic minority members (Anglin, Link, & Phelan, 2006; Rao, Feinglass, & Corrigan, 2007; Whaley, 1997). With respect to the gay community, Blacks seem to endorse stigma about gay men and lesbians more than Whites (Stokes & Peterson, 1998). Future research should examine similarities and differences of coming out in the context of mental illness versus homosexuality.

Representativeness has already been cited as a limitation of the study. Another concern is operationalizing coming out as a self-report variable. It is theoretically interesting to describe coming out as the relatively private act of weighing its pros and cons. However, coming out is also a behavior; whether the person has in fact shared this information with others. One way to assess this would be to ask research participants to list times and places where disclosure has occurred. Equally interesting would be information regarding with whom the experiences were shared and what was specifically disclosed. Future research needs to include sophisticated observations of proxies of coming out. A third discouraging result is that coming out was found to be single factors for coming out (BBO) versus staying in (RSI). Multiple perspectives about coming out and staying in, yielding a more elegant picture of the phenomenon, were not found. One reason might be too few items were written for coming out and staying in, thereby restricting available variance for the factor analyses. The COMIS items were developed from the responses of gays and lesbians. People with mental illness may have additional and distinct experiences and concerns related to coming out. Qualitative research of focus groups with people with serious mental illness may broaden the collection of items, which, in turn, may lead to additional meaningful subfactors related to coming out and staying in. Future studies could also examine the link between coming out, social support, emotional processing, and thought suppression and their impact on well-being (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009) and motivational goals for disclosing a mental illness (Garcia & Crocker, 2008). Lastly, we carved out only pieces of the self-stigma construct—perceived stigma and personal empowerment—and in the process may be testing a limited model of self-stigma. For example, using factor analyses of a sample of 82 veterans with serious mental illness, Ritsher and Phelan (2004) posed a five factor model of self-stigma, including alienation, social withdrawal, and stigma resistance. Corrigan and colleagues (2006) provided evidence supporting their four level model of self-stigma: awareness of stereotypes, agreement with stereotypes, applying these stereotypes to self, and diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy as a result.

Findings from this study have implications for people with serious mental illnesses and advocates. Coming out can serve the goals of people with mental illnesses. It can diminish the deleterious effects of self-stigma on quality of life. Therefore, an important service would be strategies that help people weigh the costs and benefits of coming out. These costs and benefits are likely to vary by situation. Disadvantages of coming out to coworkers may probably differ from disclosing at church. Hence, this kind of analysis needs to frame the challenges of coming out in the indexed situation. Various psychoeducational approaches to information and skill learning could be used to facilitate this kind of analysis. Current principles about using consumers as service providers would be relevant here. People who are uncertain about coming out, and therefore are examining advantages and disadvantages of this decision, will benefit from a peer who has been in the same situation, a person who, by virtue of being a counselor, has already navigated these decisions effectively.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by a Marie Curie Outgoing International Fellowship of the European Union to Nicolas Rüsch and by funding from NIAAA, NIMH, and the Fogarty International Center to Patrick W. Corrigan. We are grateful to Whitney Key, Norine McCarten, Karina Powell, and Anita Rajah for their support with data collection.

APPENDIX

Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale (COMIS)

Are you out about your mental illness?

In other words, have you decided to tell most of your family, friends, and acquaintances that you have a mental illness? Have you decided not to hide it?

If Yes, check here _____ and complete all the questions listed on page 2.

If No, check here _____ and complete all the questions on page 3 of this handout.

……………………………………………………………………………………

Page 2

Now please answer the remaining questions using this seven point agreement scale.

Write each score in the blank before each item

_____I came out of the closet to gain acceptance from others.

_____I came out of the closet to broaden my network of family, friends, and others.

_____I came out of the closet to support a consumer/survivor political movement.

_____I came out of the closet because I was comfortable with myself.

_____I came out of the closet to be true to myself.

_____I came out of the closet to be happier.

_____I came out of the closet to help others with the coming out process.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid being labeled (as a person with mental illness).

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid negative impact on my job.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid harming my family.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid harming my self identity.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to hide my personal life.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to maintain my personal safety.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid self shame.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid public shame.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid discrimination (e.g., at work).

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid becoming vulnerable.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to avoid stress.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet because I feared negative reactions from others.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to conform with societal demands.

_____ In the past I stayed in the closet to maintain control in my life.

……………………………………………………………………………………………

Page 3

Now please answer the remaining questions using this seven point agreement scale.

Write each score in the blank before each item.

_____ In the future I will come out of the closet to gain acceptance from others.

_____ In the future I will come out of the closet to broaden my network of family, friends, and others.

_____ In the future I will come out of the closet to support a consumer/survivor political movement.

_____ In the future I will come of the closet because I will become comfortable with myself.

_____ In the future I will come out of the closet to be true to myself.

_____ In the future I will come out of the closet to be happier.

_____ In the future I will come out of the closet to help others with the coming out process.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid being labeled (as a person with mental illness).

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid negative impact on my job.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid harming my family.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid harming my self identity.

_____ I stay in the closet to hide my personal life.

_____ I stay in the closet to maintain my personal safety.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid self shame.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid public shame.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid discrimination (e.g., at work).

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid becoming vulnerable.

_____ I stay in the closet to avoid stress.

_____ I stay in the closet because I fear negative reactions.

_____ I stay in the closet to conform to societal demands.

_____ I stay in the closet to maintain control in my life.

Contributor Information

Patrick W. Corrigan, Illinois Institute of Technology

Scott Morris, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Jon Larson, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Jennifer Rafacz, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Abigail Wassel, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Patrick Michaels, Illinois Institute of Technology.

Sandra Wilkniss, Thresholds Institute.

Karen Batia, Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights.

Nicolas Rüsch, University of Freiburg, Germany.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.) Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin DM, Link BG, Phelan JC. Racial differences in stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57:857–862. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals KP, Peplau LA. Social involvement, disclosure of sexual orientation, and the quality of lesbian relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2001;25:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Beals KP, Peplau LA, Gable SL. Stigma management and well-being: The role of perceived social support, emotional processing, and suppression. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:867–879. doi: 10.1177/0146167209334783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW. On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27:219–225. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Faber D, Rashid F, Leary M. The construct validity of empowerment among consumers of mental health services. Schizophrenia Research. 1999;38:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Matthews A. Stigma and disclosure: Implications for coming out of the closet. Journal of Mental Health. 2003;12:235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Hautamaki J, Matthews A, Kuwabara S, Rafacz J, et al. What lessons do coming out as gay men or lesbians have for people stigmatized by mental illness? Community Mental Health Journal. 2009;45:366–374. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Day NE, Schoenrade P. Staying in the closet versus coming out: Relationships between communication about sexual orientation and work attitudes. Personnel Psychology. 1997;50:147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Day NE, Schoenrade P. The relationship among reported disclosure of sexual orientation, anti-discrimination policies, top management support and work attitudes of gay and lesbian employees. Personnel Review. 2000;29:346–363. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JA, Crocker J. Reasons for disclosing depression matter: The consequences of having egosystem and ecosystem goals. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. The mark of shame: Stigma of mental illness and an agenda for change. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Spears R. Rebels with a cause: Group identification as a response to perceived discrimination from the mainstream. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1204–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Kadushin G. Family secrets: Disclosure of HIV status among gay men with HIV/AIDS to the family of origin. Social Work in Health Care. 2000;30:1–17. doi: 10.1300/J010v30n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF. A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1988;11:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. On describing and seeking to change the experience of stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills. 2002;6:201–231. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, Wozniak JF. The social rejection of former mental patients: Understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;92:1461–1500. [Google Scholar]

- Manderscheid RW, Atay JE, Crider RA. Changing trends in state psychiatric hospital use from 2002 to 2005. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:29–34. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz FE. The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illness. Journal of Health & Social Behavior. 1998;39:335–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Feinglass J, Corrigan PW. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental illness stigma. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:1020–1023. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815c046e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, Crean T. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:1042–1047. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.8.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R. The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay lesbian, and bisexual youths: stipulation and exploration of a model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29:133–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1005205630978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. Labeling mental illness: The effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review. 1997;62:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Bohus M, Jacob GA, Brueck R, Lieb K. Measuring shame and guilt by self-report questionnaires: A validation study. Psychiatry Research. 2007;150:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Powell K, Rajah A, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, et al. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: II. Emotional stress responses, coping behavior and outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2009a;110:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Larson JE, Olschewski M, et al. Self-stigma, group identification, perceived legitimacy of discrimination and service use. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009b;195:551–552. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, et al. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: I. Predictors of cognitive stress appraisal. Schizophrenia Research. 2009c;110:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, et al. Ingroup perception and responses to stigma among persons with mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009d;120:320–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Weiden PJ, Corrigan PW. Implicit versus explicit attitudes toward psychiatric medication: Implications for insight and treatment adherence. Schizophrenia, Research. 2009e;112:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV. Implicit self-stigma in people with mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010a;198:150–153. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Corrigan PW. Biogenetic models of psychopathology, implicit guilt and mental illness stigma. Psychiatry Research. 2010b doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV, Olschewski M, Corrigan PW. Automatically activated shame reactions and perceived legitimacy of discrimination: A longitudinal study among people with mental illness. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2010c;41:60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Hölzer A, Hermann C, Schramm E, Jacob GA, Bohus M, et al. Self-stigma in women with borderline personality disorder and women with social phobia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006a;194:766–773. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000239898.48701.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Lieb K, Bohus M, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006b;57:399–402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Homophobia, self-esteem, and risk for HIV among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:278–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL, Wagner PE, Gramzow R. The Test of Self-Conscious Affect-3 (TOSCA-3) Fairfax: George Mason University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ. Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:345–372. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G. Shunned: Discrimination against people with mental illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL. Ethnic and racial differences in perceptions of dangerousness of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:1328–1330. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.10.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]