Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is a crucial mediator of hindlimb collateralization and angiogenesis. Within tissues there are nitrosyl-heme proteins which have the potential to generate NO under conditions of hypoxia or low pH. Low level irradiation of blood and muscle with light in the far red/near infrared spectrum (670 nm, R/NIR) facilitates NO release. Therefore, we assessed the impact of red light exposure on the stimulation of femoral artery collateralization. Rabbits and mice underwent unilateral resection of the femoral artery and chronic R/NIR treatment. The direct NO scavenger carboxy-PTIO and the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor L-NAME were also administered in the presence of R/NIR. DAF fluorescence assessed R/NIR changes in NO levels within endothelial cells. In vitro measures of R/NIR induced angiogenesis were assessed by endothelial cell proliferation and migration. R/NIR significantly increased collateral vessel number which could not be attenuated with L-NAME. R/NIR induced collateralization was abolished with c-PTIO. In vitro, NO production increased in endothelial cells with R/NIR exposure, and this finding was independent of NOS inhibition. Similarly R/NIR induced proliferation and tube formation in a NO dependent manner. Finally, nitrite supplementation accelerated R/NIR collateralization in wild type c57Bl/6 mice. In an eNOS deficient transgenic mouse model, R/NIR restores collateral development. In conclusion, R/NIR increases NO levels independent of NOS activity, and leads to the observed enhancement of hindlimb collateralization.

Keywords: Hindlimb Collateralization, Nitric Oxide, Angiogenesis, Low level light therapy, Nitrosyl-hemoglobin

1.0. Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is an enormous clinical problem with 8 million Americans being treated for symptoms such as intermittent claudication, and critical limb ischemia [1]. Therapies have focused on risk reduction, anti-platelet medications, and vasodilators such as cilostazol [2–4]. Surgical intervention with stent placement or bypasses of affected blood vessels is reserved for patients with severe critical limb ischemia and is often ineffective, therefore the risk for limb amputation remains high.

One treatment would be to stimulate collateral blood vessels within the ischemic limb and restore blood flow to the distal extremity. NO (nitric oxide) mediates collateralization through the production of growth factors e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin, and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) [5–7]. NO is predominantly produced by enzymatic reduction of L-arginine to L-citrulline via nitric oxide synthases (NOS). However there is increasing interest in NOS- independent NO generation, particularly during hypoxia or anoxia, when NOS is inactive [8,9]. Nitrite can be enzymatically reduced to NO by molecules such as deoxyhemoglobin [10–13], deoxymyoglobin [14], xanthine oxidoreductase [9,15], cytochrome c oxidase [16] and NOS itself [17]. The heme moiety in these proteins binds the newly formed NO, thus generating nitrosyl storage pools of potentially bio-available NO.

Previously, we identified that light in the far red/near infrared spectrum (670 nm, R/NIR) releases NO from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin. NO generated in this fashion was responsible for R/NIR induced cardioprotection, thereby supporting the concept these storage pools of NO can be manipulated for therapeutic purposes [13]. Light exposure between 630nm and 830nm has been extensively studied in vivo and in vitro [18–21]. In this range there is improved tissue penetration due to limited melanin absorption [22]. Radiant heat production in R/NIR exposed tissue is below 0.5°C, because of limited water absorption by light [23,24]. Based on this evidence, we propose repetitive application of R/NIR (670 nm) will stimulate collateral blood vessel development independent of NOS. We further propose this increase in NO is physiologically significant so as to allow peripheral vascular collateralization in a NO deficient model.

2.0. Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures and protocols used in this investigation were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Furthermore, all conformed to the Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals of the American Physiologic Society and were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.1. R/NIR Sources

The 670nm LED light source with power output up to 100mW/cm2 was obtained from Quantum Devices and 60mW/cm2 light source from NIR Technologies. Power output was measured with a light meter (X97, GigaHertz-Optik) at the surface to report actual irradiance intensity. The light sources were placed 2.5 cm from their target in all animal experiments. In vitro, culture dishes and slides were placed directly on the light source. The irradiance intensities listed below reflect the values obtained at the skin surface for in vivo studies, or the bottom of the culture dish for in vitro studies.

2.2. Rabbit Model of Hind-limb Ischemia

New Zealand White rabbits underwent unilateral femoral artery excision according to previously published protocols [25]. After a 5-day recovery, rabbits were randomized into 6 groups. Group 1 (n=6) underwent ischemia alone and group 2 (n=6) underwent ischemia with a daily R/NIR exposure (60mW/cm2 × 10 min = 36 J/day) for 14 days. Group 3 (n=6) received 0.5g/L of L-NAME (Sigma) in their drinking water for 14 days and Group 4 (n=6) received L-NAME with R/NIR exposure. Group 5 (n=6) received infusions of 0.17mg/kg/min carboxy-PTIO (c-PTIO, Alexa chemical), a NO scavenger 1 min prior to R/NIR through 2 min post R/NIR. Group 6 (n=6) received daily infusion of c-PTIO without R/NIR. After 14 days, rabbits were anesthetized, the left carotid was cannulated, and both femoral arteries were injected with 10cc Omnipaque contrast media, and imaged with radiographic fluorography. Collateral blood vessel number was directly counted by 2 independent and blinded reviewers.

2.3. Endothelial Cell Proliferation Assay

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were grown to passage 4–6 in EGM media (Lonza), and then seeded (10,000 cells/well) on a 24 well culture plate (Costar). Cells were exposed to R/NIR (100mW/cm2/day) for 4 days. The exposure duration varied to generate an energy dose response curve for cell proliferation. After the last exposure, cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized and counted using a hemocytometer. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate

2.4. Western Analysis

Vessels from the ischemic and control limbs were excised, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and isolated using protease inhibitor supplemented NP40 lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors. Protein extracts were measured by the BCA method (Pierce), resolved using standard SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were probed with mouse anti-VEGF antibody (1:200, Santa Cruz). Membranes were stripped and re-probed with mouse alpha- actin (1:200, Santa Cruz). Densitometry was performed using Image J software. Four samples in each group were analyzed. Data was normalized to the non-ischemic limb.

2.5. Endothelial Cell Tube Formation

Human coronary endothelial cells (HUVECs) were grown to passage 4–6 in HUVEC media (Cell Applications). Fibrin gels were prepared according to previously published protocols [26,27]. HUVECs (40,000 cells/well), were seeded on the surface of the three-dimensional matrix and incubated 1 hr prior to exposure with HUVEC media alone, Group 2 with 50 ng purified VEGF/well, Group 3 with L-NAME (1 mM), and Group 4 with c-PTIO (100μM). One plate was exposed to R/NIR (50mW/cm2 × 150s =7.5J), and a control plate was not exposed. Thirty minutes post-exposure, the media was exchanged for standard media in order to avoid cell death secondary to extreme chronic NO depletion. This process was repeated daily for a total of 4 exposures. Experiments were performed in quadruplicate.

2.6. NO Detection by DAF-2 (diaminofluorescein) Fluorescence

HUVECs (passage 4–6) were seeded (25,000 cells/chamber) on chamber slides (Nunc) and grown to 90% confluence. Individual cell chambers incubated for 30 min in DMEM, 1mM L-NAME, or 100 μM carboxy-PTIO, before 4-amino-5methylamino-2′7′-diamiofluorescein diacetate (2 μM DAF-2, Invitrogen) was added prior to exposure. Cells were then irradiated for 7.5J (150 s at 50mW/cm2), incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and then mounted for confocal microscopy. Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U microscope equipped with EZC12 software. Fluorescence was monitored with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 510 nm. Images were analyzed using Nikon Element software to measure mean fluorescence intensity. Five images from each group were measured.

2.7. Mouse Hind-limb Collateralization Model

C57Bl/6 mice (n=6) or endothelial NOS knock-out mice (eNOS−/−, n=6) underwent femoral artery ligation and excision distal to the femoral profundus and proximal to the saphenous and popliteal arteries [28,29]. The mice were placed within a box containing a transparent floor which rested directly on the light source. Beginning immediately after surgery, C57 Bl/6 or eNOS−/− mice were exposed to R/NIR light (60mW/cm2 × 10 min = 36J/day) for 14 days. Additional groups of C57Bl6 and eNOS −/− mice underwent femoral artery ligation and excision with sodium nitrite supplementation (8.2 μg/kg/day, for 14 days, i.p.), and then further divided into receiving daily R/NIR or not receiving R/NIR [30].

2.8. Collateral Blood Flow

Laser doppler flow imaging was performed on all mice for noninvasive measurement of blood flow (Moor Instruments, UK). Mice were anesthetized with 1.25% isoflurane, allowed to acclimate on a heating pad to maintain body temperature, and then scanned [28]. Flow intensities in both limbs were measured on days 0, 3, 7, and 14. Data was expressed as the ratio of mean intensity between the ischemic limb and the contra-lateral control.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons were made using a one way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni t-test, or a Student’s t-test. Values for p<0.05 were considered significant.

3.0. Results

3.1. Application of R/NIR stimulates femoral artery collateralization

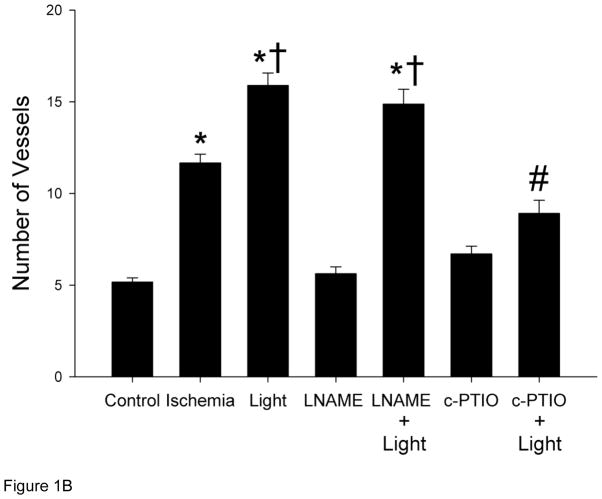

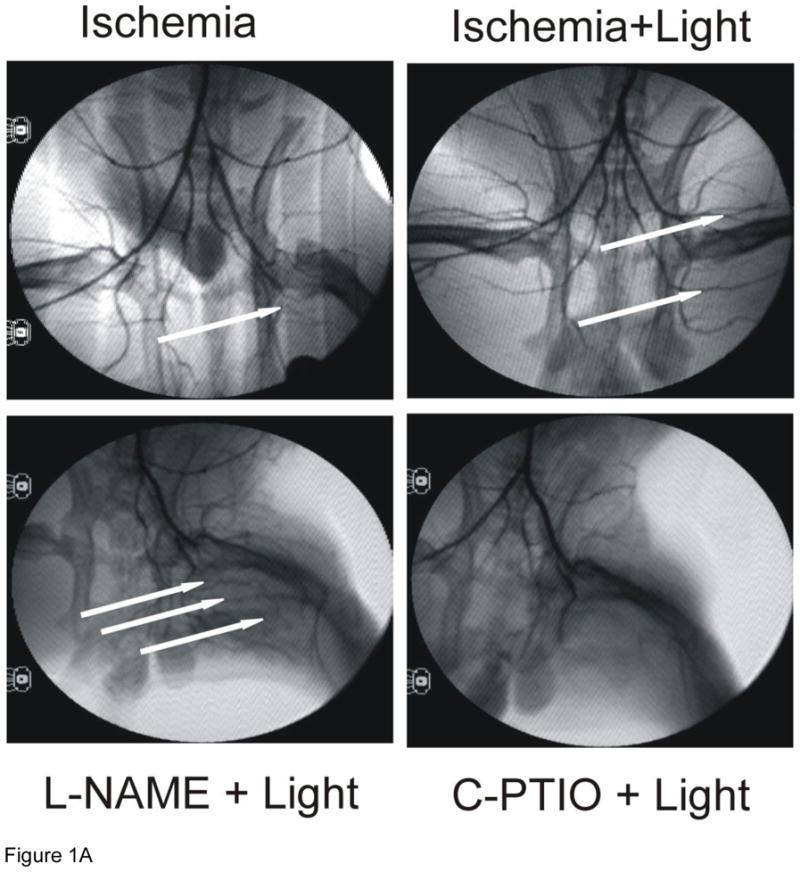

To assess the effect of R/NIR on femoral artery collateralization, a rabbit hind limb ischemia model was employed. Figure 1 summarizes angiographic data collected at day 19 (5 day recovery plus 14 day protocol). Ischemia stimulated collateral vessels (11.7 ± 0.47; mean ± SEM) vs. control, (5.2 ± 0.23; p<.001), but R/NIR further increased blood vessel growth as compared to ischemia alone (15.9 ± 0.67 vs. 11.7 ± 0.47, p<0.001). Inhibition of NOS with L-NAME abolished collateral development stimulated by ischemia alone (5.6 ± 0.37 vs. 11.7 ± 0.47, p<0.001), however, R/NIR induced collateralization was unaffected (14.9 ± 0.81 vs. 15.9 ± 0.67). When c-PTIO was administered, ischemia (6.7 ± 0.42 vs. 11.7 ± 0.47, p<0.001) and R/NIR collateralization (8.9 ± 0.72 vs. 15.9 ± 0.67, p<0.001) was abolished. These studies suggest daily R/NIR enhances collateral development through an NO mediated mechanism, but does not require NOS as a source of the NO.

Figure 1. R/NIR increases collateral vessels in rabbits.

A) Representative images from each group (n=6). B) R/NIR increases collateral vessel number over ischemia. *p<0.001 vs. control, †p< 0.001 vs. ischemia, #p<0.001 vs. R/NIR.

3.2. HUVECs produce NO in response to R/NIR

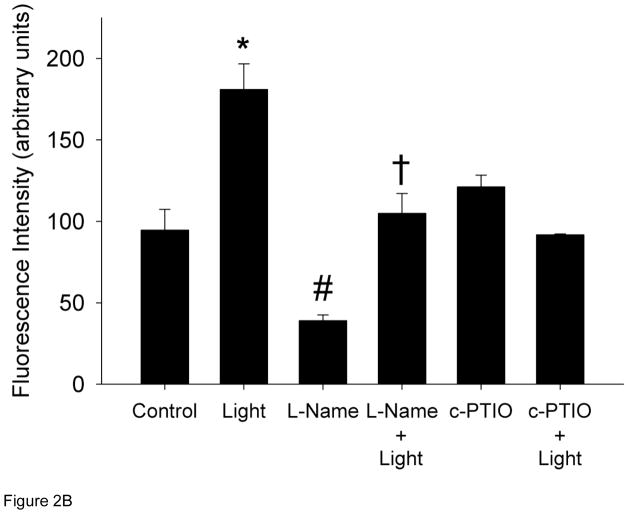

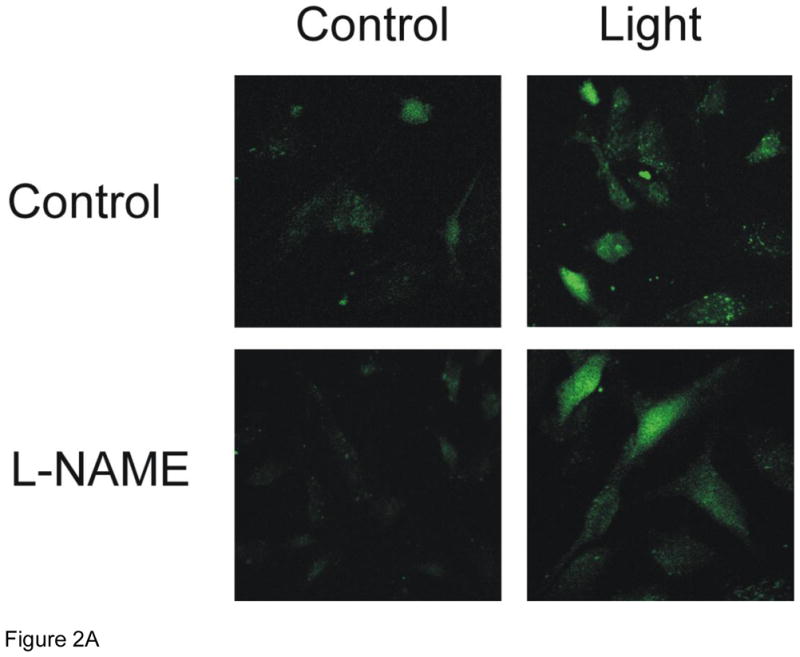

Cultured HUVECs were exposed to R/NIR in the presence of DAF-2 to quantify relative changes in NO. One exposure of R/NIR to HUVECs in Figure 2 (60 mW/cm2 × 150 s = 7.5J/cm2) increased fluorescence intensity (181 a.u. vs. 95 a.u., p<0.001). Pre-incubation with L-NAME, lead to a significant decrease in fluorescence when compared to control (39 a.u. vs. 95 a.u., p<0.05), but after R/NIR exposure the fluorescence intensity significantly increased (105 a.u. vs. 39 a.u., p <0.01). NO baseline levels were not affected by c-PTIO, but c-PTIO attenuated R/NIR stimulated increases in NO (121 a.u. vs 181 a.u., p<0.001) confirming NO increases by R/NIR are independent of functional NOS. The finding that c-PTIO did not affect baseline fluorescence reflects the oxidation of NO to nitrite by c-PTIO. In the presence of NO abundance and nitrite, N2O3 is produced, which reacts with DAF-2 to generate fluorescence [31,32].

Figure 2. R/NIR increases DAF-2 fluorescence.

A) Representative confocal images of HUVECs pretreated with and without L-NAME and R/NIR B). Mean fluorescence intensity quantification. *p<0.001 vs control, #p<0.05 vs. control, †p< 0.01 vs. L-NAME.

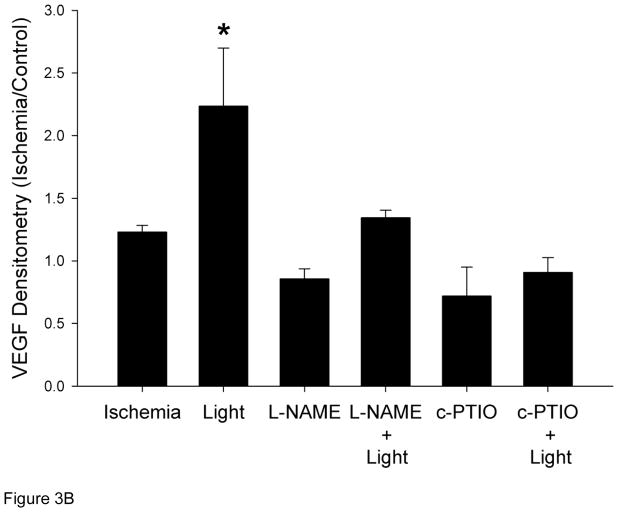

3.3. R/NIR increases Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF)

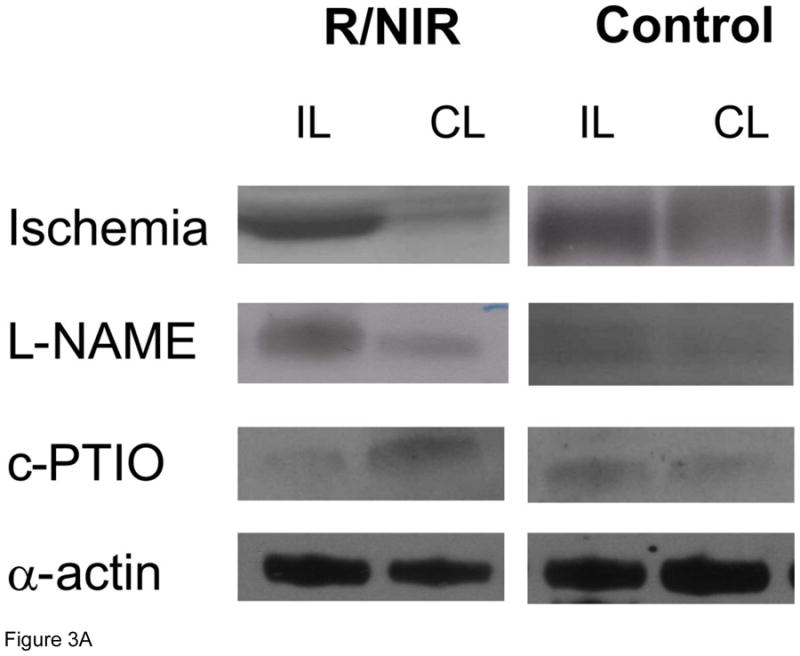

One mechanism by which NO mediates collateralization is through stimulation of growth factors [27,33]. VEGF expression increased 1.2 fold in the collateral limb over the non-ischemic control limb (Figure 3). With R/NIR collateralization, VEGF expression increased 2.5 fold (p<0.01). Although L-NAME abolished ischemia induced VEGF expression it did not attenuate R/NIR increases in VEGF. VEGF expression was completely abolished with c-PTIO.

Figure 3. VEGF expression in collateral dependent hind limb (n=4).

A) Representative western blots. B) R/NIR increased VEGF expression in the ischemic limb (IL) vs. non ischemic control (CL). *p<0.01 vs. ischemia.

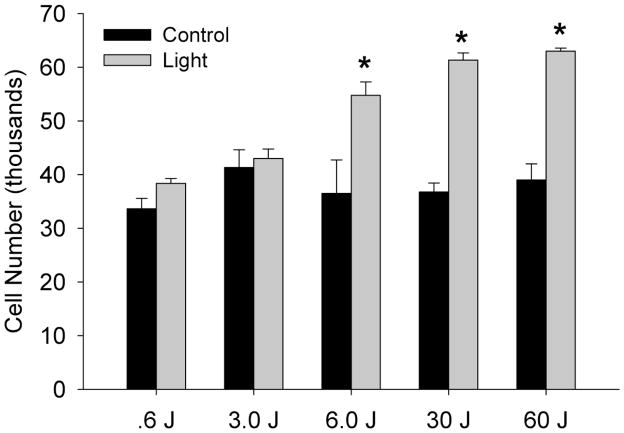

3.4. R/NIR stimulates cellular proliferation

Endothelial cell proliferation is a hallmark of angiogenesis. HUVECs were repetitively exposed to variable doses of R/NIR (Figure 4). Doses of R/NIR below 6 J could not stimulate proliferation, however at 6 J, cell number increased almost 60% (p<0.05). The proliferative effect of light plateaued at 30 J, indicating the optimal response to light is between 6J and 30J.

Figure 4. R/NIR stimulates endothelial proliferation.

Increasing energy dose of R/NIR stimulates HUVEC proliferation. n=4 *p<0.05 vs. control.

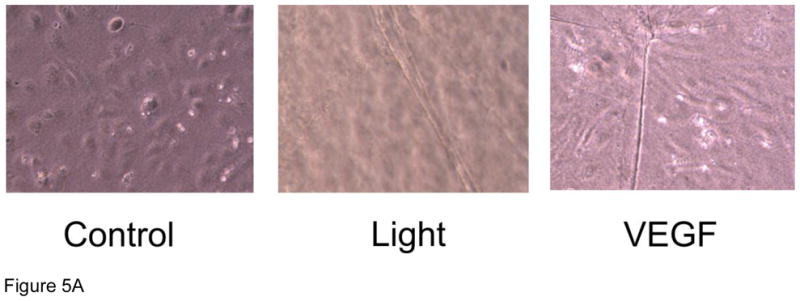

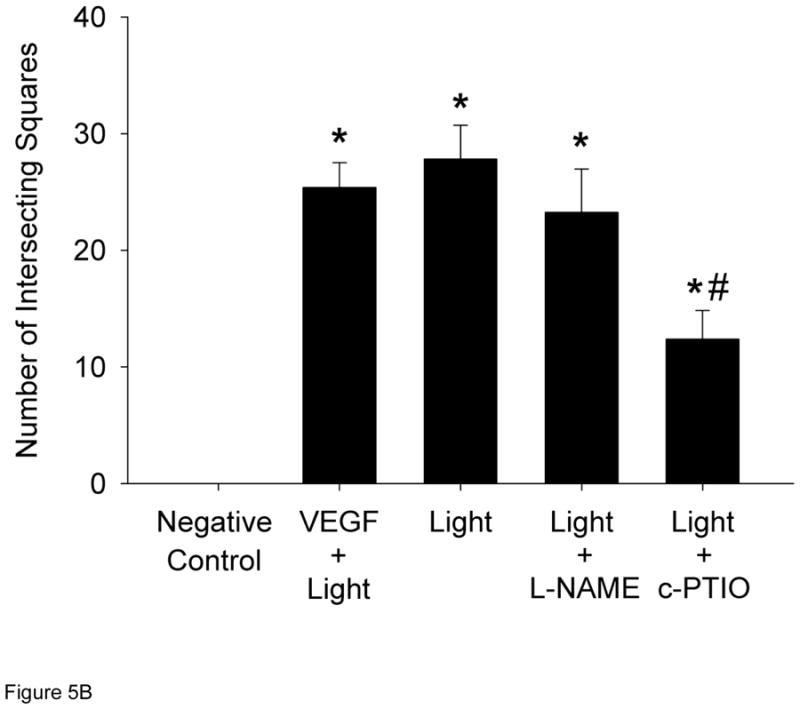

3.5. R/NIR stimulates cellular tube formation

Cell migration is an additional measure of angiogenesis therefore HUVECs were seeded on a fibrin matrix gel and repetitively exposed to R/NIR. HUVECs formed significant tubes (28 intersecting squares vs. 0; p<0.05; Figure 5) when stimulated with R/NIR. L-NAME did not significantly impair endothelial cell migration (23 vs. 28 intersecting squares), but c-PTIO (100 μM) abolished cell migration in response to R/NIR stimulation, again confirming a key role for NO in light induced collateralization (12 vs. 28 intersecting squares, p<0.05). Purified VEGF stimulated HUVECs to form tubes, thus verifying the integrity of the cells in culture.

Figure 5. R/NIR stimulates endothelial migration.

A) Representative images HUVECs ± R/NIR treatment and VEGF positive control. B) Quantified intersecting squares reflect R/NIR tube formation in the presence of NOS inhibitor (L-NAME) and the NO scavenger (c-PTIO). *p<0.05 vs. control; #p<0.05 vs. R/NIR.

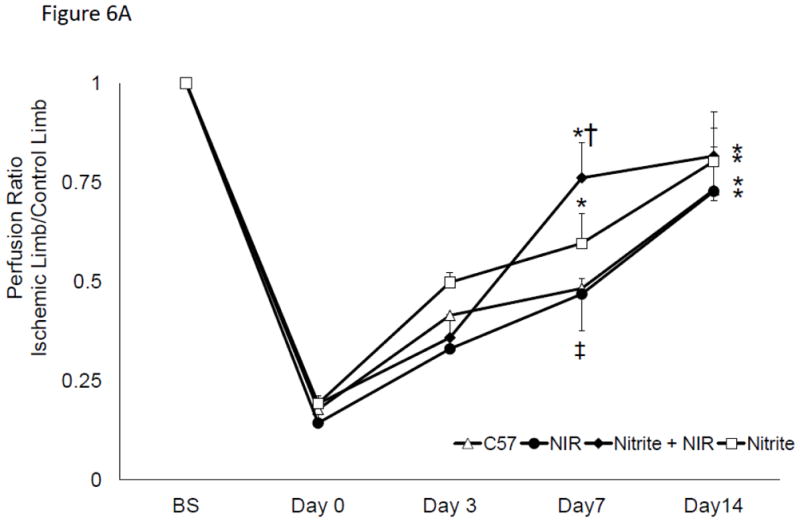

3.6. R/NIR restores collateralization in eNOS deficient mice

Hind limb collaterals were stimulated in C57 Bl/6 mice after 14 days of ischemia. Blood flow in the C57Bl/6 group was significantly elevated at Day 7 (0.48 (±0.1) vs. 0.17 (±0.02, p<0.001 vs. day 0), n=7) and increased to 0.71 (±0.08 p<0.001 vs day 0, n=7) by day 14 (Figure 6A). Daily R/NIR treatment could not significantly increase collateral flow over ischemia alone. Since R/NIR treatment is presumed to work through release of NO from nitrosyl-hemeproteins, sub-stimulatory doses of sodium nitrite (8 μg/kg/day) were combined with daily R/NIR irradiation were performed. As expected collateral blood flow did not significantly increase with nitrite alone when compared to the C57Bl/6 control (Figure 6A). When nitrite was administered with daily R/NIR, an increase in collateral blood flow was observed at day 7 (0.76±0.09, n=7) and was significantly increased when compared to ischemia (0.48±0.1, p<0.01), or R/NIR (0.46±0.04, p<0.01, n=7) (Figure 6A). This observed increased in collateral blood flow in the combined nitrite and R/NIR groups was no longer present at Day 14 when compared to ischemia, nitrite or R/NIR alone.

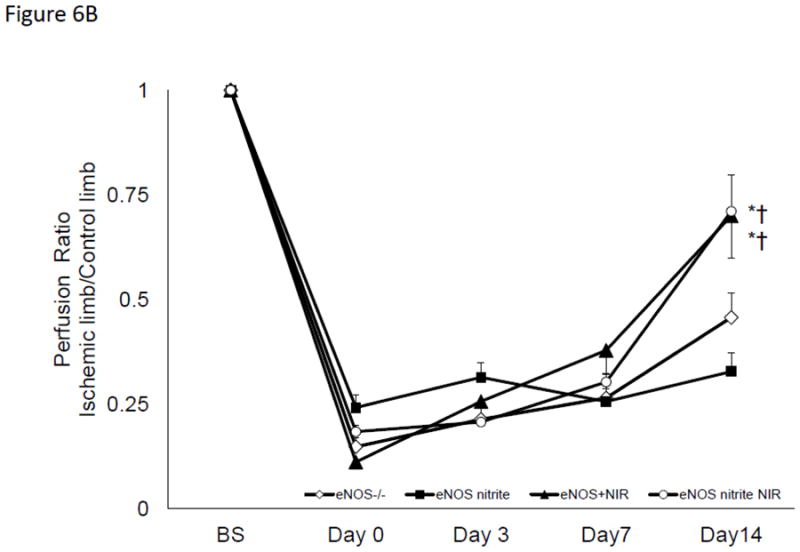

Figure 6. R/NIR increases collateral flow in eNOS deficient mice.

A) Blood flow intensity ratio ischemic/control for c57Bl/6 with nitrite and R/NIR. *p<0.001 vs. Day 0, ‡p<0.05 vs Day O †p<0.01 vs. R/NIR B). Intensity ratio ischemic/control for eNOS−/− with nitrite and R/NIR. *p<0.001 vs. Day 0.

If R/NIR exposure stimulates NO production independent of NOS, then it would be expected to restore collateralization in NOS deficient states. Mice which contain a transgenic deletion of eNOS underwent femoral artery ligation. Blood flow in the ischemic limb was significantly decreased at all time points, with a peak flow ratio of 0.45 (n=9; p<0.05), consistent with impaired collateralization (Figure 6B) [6]. Daily R/NIR exposure significantly increased blood flow in eNOS knockout mice (0.70, n=10; p<0.05 vs eNOS control) at Day 14. Chronic administration of sodium nitrite did not stimulate increases in collateral blood flow. When sodium nitrite was combined with R/NIR treatment, collateral flow could not be significantly increased over R/NIR treatment alone. Thus, R/NIR can effectively stimulate collateral blood flow in the absence of eNOS.

4.0. Discussion

The findings of this investigation indicate that repeated R/NIR exposure stimulates angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro. In a hind limb model, R/NIR significantly augmented collateralization in a NO dependent manner, since NO scavenging can abolish R/NIR collateralization. These results also indicate the NO source was independent of NOS, since chronic NOS inhibition was unable to inhibit R/NIR collateralization. In the presence of chronic nitrite treatment and R/NIR, ischemia induced angiogenesis was accelerated in wild type c57Bl/6 by day 7. Although R/NIR exposure could restore collateral blood flow in a model of transgenic deletion of eNOS, sodium nitrite treatment could not further enhance collateralization. It may be that eNOS−/− mice require higher doses of nitrite to overcome their chronic NO deficiency.

In vitro, R/NIR increased intracellular NO in HUVECs that was independent of NOS. While a specific intracellular source of NO was not identified in this study, the argument for many potential NO donors can be proposed. Cytochrome c oxidase reversibly binds NO as a nitrosyl- adduct or as nitrite, depending on the concentration of reduced cytochrome c and O2 [16]. It absorbs light in the far red/near infrared spectrum, and is the likely photoacceptor modulating neuroprotection from methanol toxicity [34]. Cytochrome c complexed with mitochondrial cardiolipin binds NO, which is also photosensitive [35]. Guanylate cyclase, the chemoreceptor for NO mediated vascular relaxation, is activated when NO binds its heme site and is photosensitive [36]. Cytoglobin, the newest member of the globin family, is a hexacoordinate heme protein with nitrite reductase capable of reducing nitrite to NO in the presence of hypoxia [37]. It’s abundantly expressed in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells [37,38]. Nitrite reduction and NO binding to the heme iron by cytoglobin is possible when the heme-histidine bond is in a five-coordinate state, which results in a free binding site for nitrite or NO respectively. Approximately 0.6% of cytoglobin exhibits this binding affinity when the pentacoordinate state is at equilibrium with the hexacoordinate state [37]. Since cytoglobin is present in micromolar amounts in cells, there is still potential for it to be a source of NO generated by R/NIR. S-nitrosothiols are an additional source to be studied because they have photosensitivity at wavelengths between 550- 600nm [39,40]. In the presence of hematoporphyrins, there is increased photosensitivity of some nitrosothiol compounds at 650 nm [40]. It is critical to note that photolysis of sodium nitrite to yield NO does not occur at 670 nm, but rather in the ultraviolet range of wavelengths [41]

An effective collateral circulation relies on vascular remodeling, for which endothelial cell proliferation and migration is critical. Growth factor expression is necessary for this process, and this study focused on VEGF specifically, as it is well characterized in collateral development and can be stimulated by NO [27]. Recently, cytochrome c oxidase derived NO contributes to HIF-1–α, thus leading to accumulation of this transcription factor, and ultimately an increase in VEGF expression. [42]. The modest expression of VEGF in the ischemic group reflects the decreased hypoxic stimulus at day 14 when collateral development, and presumably perfusion had increased. R/NIR stimulated increases in VEGF suggest the continued generation of NO provides a chronic stimulus for VEGF expression.

There are several limitations to the current study. Although the action of R/NIR light appears independent of NOS derived NO, we did not directly identify a sole source of NO which is essential for angiogenesis. As evidenced from the discussion above, there are numerous and abundant intracellular sources of nitrosyl-heme proteins which could generate free NO upon light stimulation. This will require further analysis using genetically modified protein expression. Additionally, the current conditions for R/NIR remain only broadly defined. Within the literature R/NIR has been used to reduce infarct size, protect neurons from methanol toxicity, heal chemotherapy induced mucositis, and stimulate angiogenesis [18,21,34,43–47]. However the irradiance and dosing parameters, i.e. wavelength, power output, distance, density, and time vary in each study. Another factor is tissue penetration, which reflects the lower doses of energy required for single cell monolayers in culture, when compared to multiple layers of tissue in vivo. There is increasing interest to “tune” these parameters to specific endpoints, e.g. measured reactive oxygen species, NF-κB, and caspase activity [48,49].

4.1.Conclusion

R/NIR light in low doses can stimulate peripheral collateralization via increases in NO. This investigation provides further evidence that biologically significant amounts of NO do not require functional NOS. In fact, the novelty of R/NIR treatment is that NO generation occurs despite conditions, like hypoxia and acidosis, which inactivate NOS. Thus, an alternative and redundant system to NOS exists to generate NO. Ischemic tissues may be able to increase nitrosyl storage pools by the addition of nitrite, and R/NIR can subsequently be used to stimulate NO release in a site specific manner. Safe NO delivery by R/NIR offers considerable therapeutic advantages.

Highlights.

Low levels of red/near infrared light stimulate collateral formation in the hindlimb.

Nitric oxide levels increase in response to light.

Nitric oxide increases are independent of functional nitric oxide synthases.

Endothelial cells proliferate and migrate in response to light.

Repetitive doses of red light stimulate collateralization in an impaired model of angiogenesis where eNOS is deficient.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Krolikowski, John Tessmer, Deron Jones, David Schwabe and Janine Struve for their technical assistance

Funding source: This research was sponsored by HL-089779 D.W.

Abbreviations and Definitions

- R/NIR

Red/Near Infrared Light wavelength peak at 670 nm

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NOS

Nitric oxide synthase

- HUVEC

Human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Peripheral Arterial Disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease)--summary of recommendations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1383, 97. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000240426.53079.46. quiz 1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hori A, Shibata R, Morisaki K, Murohara T, Komori K. Cilostazol Stimulates Revascularisation in Response to Ischaemia via an eNOS-Dependent Mechanism. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2012;43:62–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chi YW, Lavie CJ, Milani RV, White CJ. Safety and efficacy of cilostazol in the management of intermittent claudication. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:1197–203. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitz JI, Byrne J, Clagett GP, Farkouh ME, Porter JM, Sackett DL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: a critical review. Circulation. 1996;94:3026–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babaei S, Teichert-Kuliszewska K, Monge JC, Mohamed F, Bendeck MP, Stewart DJ. Role of nitric oxide in the angiogenic response in vitro to basic fibroblast growth factor. Circ Res. 1998;82:1007–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, Bauters C, Masuda H, Kalka C, et al. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2567. doi: 10.1172/JCI1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluge A, Zimmermann R, Weihrauch D, Mohri M, Sack S, Schaper J, et al. Coordinate expression of the insulin-like growth factor system after microembolisation in porcine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:324–31. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:156–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gladwin MT, Schechter AN, Kim-Shapiro DB, Patel RP, Hogg N, Shiva S, et al. The emerging biology of the nitrite anion. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:308–14. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1105-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB. The functional nitrite reductase activity of the heme-globins. Blood. 2008;112:2636–47. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-115261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1498–505. doi: 10.1038/nm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dejam A, Hunter CJ, Pelletier MM, Hsu LL, Machado RF, Shiva S, et al. Erythrocytes are the major intravascular storage sites of nitrite in human blood. Blood. 2005;106:734–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohr NL, Keszler A, Pratt P, Bienengraber M, Warltier DC, Hogg N. Enhancement of nitric oxide release from nitrosyl hemoglobin and nitrosyl myoglobin by red/near infrared radiation: potential role in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiva S, Huang Z, Grubina R, Sun J, Ringwood LA, MacArthur PH, et al. Deoxymyoglobin is a nitrite reductase that generates nitric oxide and regulates mitochondrial respiration. Circ Res. 2007;100:654–61. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260171.52224.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godber BLJ, Doel JJ, Sapkota GP, Blake DR, Stevens CR, Eisenthal R, et al. Reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide catalyzed by xanthine oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7757. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarti P, Forte E, Mastronicola D, Magnifico MC, Arese M. The Chemical Interplay between Nitric Oxide and Mitochondrial Cytochrome c Oxidase: Reactions, Effectors and Pathophysiology. International Journal of Cell Biology. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/571067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gautier C, van Faassen E, Mikula I, Martasek P, Slama-Schwok A. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase reduces nitrite anions to NO under anoxia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:816–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodgson BD, Margolis DM, Salzman DE, Eastwood D, Tarima S, Williams LD, et al. Amelioration of oral mucositis pain by NASA near-infrared light-emitting diodes in bone marrow transplant patients. Support Care Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caetano KS, Frade MA, Minatel DG, Santana LA, Enwemeka CS. Phototherapy improves healing of chronic venous ulcers. Photomed Laser Surg. 2009;27:111–8. doi: 10.1089/pho.2008.2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kolyakov SF, Afanasyeva NI. Absorption measurements of a cell monolayer relevant to phototherapy: reduction of cytochrome c oxidase under near IR radiation. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2005;81:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eells JT, Wong-Riley MT, VerHoeve J, Henry M, Buchman EV, Kane MP, et al. Mitochondrial signal transduction in accelerated wound and retinal healing by near-infrared light therapy. Mitochondrion. 2004;4:559–67. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen-Reece H, Elwell CE, Harkness W, Goldstone J, Delpy DT, Wyatt JS, et al. Use of near infrared spectroscopy to estimate cerebral blood flow in conscious and anaesthetized adult subjects. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:43–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozkurt A, Onaral B. Safety assessment of near infrared light emitting diodes for diffuse optical measurements. Biomed Eng Online. 2004;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stadler I, Lanzafame RJ, Oskoui P, Zhang RY, Coleman J, Whittaker M. Alteration of skin temperature during low-level laser irradiation at 830 nm in a mouse model. Photomed Laser Surg. 2004;22:227–31. doi: 10.1089/1549541041438560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckwalter JB, Curtis VC, Valic Z, Ruble SB, Clifford PS. Endogenous vascular remodeling in ischemic skeletal muscle: a role for nitric oxide. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:935–40. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00378.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsunaga T, Weihrauch DW, Moniz MC, Tessmer J, Warltier DC, Chilian WM. Angiostatin inhibits coronary angiogenesis during impaired production of nitric oxide. Circulation. 2002;105:2185–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015856.84385.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunaga T, Warltier DC, Weihrauch DW, Moniz M, Tessmer J, Chilian WM. Ischemia-induced coronary collateral growth is dependent on vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide. Circulation. 2000;102:3098–103. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalothorn D, Clayton JA, Zhang H, Pomp D, Faber JE. Collateral density, remodeling, and VEGF-A expression differ widely between mouse strains. Physiological genomics. 2007;30:179–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00047.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limbourg A, Korff T, Napp LC, Schaper W, Drexler H, Limbourg FP. Evaluation of postnatal arteriogenesis and angiogenesis in a mouse model of hind-limb ischemia. Nature protocols. 2009;4:1737–48. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar D, Branch BG, Pattillo CB, Hood J, Thoma S, Simpson S, et al. Chronic sodium nitrite therapy augments ischemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:7540–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arita N, Cohen M, Tokuda G, Yamasaki H. Fluorometric detection of nitric oxide with diaminofluoresceins (DAFs): applications and limitations for plant NO research. Nitric Oxide in Plant Growth, Development and Stress Physiology. 2007:269–80. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rümer S, Krischke M, Fekete A, Mueller MJ, Kaiser WM. DAF-fluorescence without NO: Elicitor treated tobacco cells produce fluorescing DAF-derivatives not related to DAF-2 triazol. Nitric Oxide. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parenti A, Morbidelli L, Cui XL, Douglas JG, Hood JD, Granger HJ, et al. Nitric oxide is an upstream signal of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 activation in postcapillary endothelium. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4220–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong-Riley MT, Liang HL, Eells JT, Chance B, Henry MM, Buchmann E, et al. Photobiomodulation directly benefits primary neurons functionally inactivated by toxins: role of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4761–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silkstone G, Kapetanaki SM, Husu I, Vos MH, Wilson MT. Nitric Oxide Binding to the Cardiolipin Complex of Ferric Cytochrome c. Biochemistry. 2012 doi: 10.1021/bi300582u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Negrerie M, Bouzhir L, Martin JL, Liebl U. Control of nitric oxide dynamics by guanylate cyclase in its activated state. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46815–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102224200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Hemann C, Abdelghany TM, El-Mahdy MA, Zweier JL. Characterization of the mechanism and magnitude of cytoglobin-mediated nitrite reduction and nitric oxide generation under anaerobic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.342378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu X, Follmer D, Zweier JR, Huang X, Hemann C, Liu K, et al. Characterization of the function of cytoglobin as an oxygen-dependent regulator of nitric oxide concentration. Biochemistry. 2012;51:5072–82. doi: 10.1021/bi300291h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh RJ, Hogg N, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Mechanism of nitric oxide release from S-nitrosothiols. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18596–603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh RJ, Hogg N, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. Photosensitized decomposition of< i> S</i>-nitrosothiols and 2-methyl-2-nitrosopropane Possible use for site-directed nitric oxide production. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:47–51. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00065-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsunaga K, Furchgott RF. Interactions of light and sodium nitrite in producing relaxation of rabbit aorta. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:687–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ball KA, Nelson AW, Foster DG, Poyton RO. Nitric oxide produced by cytochrome c oxidase helps stabilize HIF-1α in hypoxic mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuby H, Maltz L, Oron U. Modulations of VEGF and iNOS in the rat heart by low level laser therapy are associated with cardioprotection and enhanced angiogenesis. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:682–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirsky N, Krispel Y, Shoshany Y, Maltz L, Oron U. Promotion of angiogenesis by low energy laser irradiation. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2002;4:785–90. doi: 10.1089/152308602760598936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whelan HT, Buchmann EV, Dhokalia A, Kane MP, Whelan NT, Wong-Riley MT, et al. Effect of NASA light-emitting diode irradiation on molecular changes for wound healing in diabetic mice. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2003;21:67–74. doi: 10.1089/104454703765035484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang HL, Whelan HT, Eells JT, Meng H, Buchmann E, Lerch-Gaggl A, et al. Photobiomodulation partially rescues visual cortical neurons from cyanide-induced apoptosis. Neuroscience. 2006;139:639–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Desmet KD, Paz DA, Corry JJ, Eells JT, Wong-Riley MT, Henry MM, et al. Clinical and experimental applications of NIR-LED photobiomodulation. Photomed Laser Surg. 2006;24:121–8. doi: 10.1089/pho.2006.24.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang R, Mio Y, Pratt PF, Lohr N, Warltier DC, Whelan HT, et al. Near infrared light protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia and reoxygenation injury by a nitric oxide dependent mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang YY, Chen AC, Carroll JD, Hamblin MR. Biphasic dose response in low level light therapy. Dose Response. 2009;7:358–83. doi: 10.2203/dose-response.09-027.Hamblin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]