Abstract

Lysosomes contain various hydrolases that can degrade proteins, lipids, nucleic acids and carbohydrates. We recently discovered “RNautophagy,” an autophagic pathway in which RNA is directly taken up by lysosomes and degraded. A lysosomal membrane protein, LAMP2C, a splice variant of LAMP2, binds to RNA and acts as a receptor for this pathway. In the present study, we show that DNA is also directly taken up by lysosomes and degraded. Like RNautophagy, this autophagic pathway, which we term “DNautophagy,” is dependent on ATP. The cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C also directly interacts with DNA, and LAMP2C functions as a receptor for DNautophagy, in addition to RNautophagy. Similarly to RNA, DNA binds to the cytosolic sequences of fly and nematode LAMP orthologs. Together with the findings of our previous study, our present findings suggest that RNautophagy and DNautophagy are evolutionarily conserved systems in Metazoa.

Keywords: LAMP2, LAMP-2, LAMP2C, LAMP-2C, autophagy, RNA, RNautophagy, DNA, DNautophagy

Introduction

Lysosomes contain various hydrolases that can degrade proteins, lipids, nucleic acids and carbohydrates,1,2 as well as organelles.3 Despite such a diversity of hydrolases observed within lysosomes, studies on selective autophagy have been mainly focused on its protein-targeting machineries.4-6 We recently discovered a novel type of autophagy, which we term RNautophagy.7 In this pathway, RNA is directly taken up by lysosomes in an ATP-dependent manner.

Lysosomes are characterized not only by various hydrolases, but also by a high abundance of membrane-integrated glycoproteins. LAMP2 is a major lysosomal membrane glycoprotein with a single transmembrane region.8 We have shown that LAMP2C, one of three splice variants of LAMP2, functions as a receptor for this pathway.7 The three LAMP2 isoforms, LAMP2A, LAMP2B and LAMP2C, share identical luminal regions, but have different C-terminal cytosolic tails.8 We have shown that the cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C directly binds to RNA.7 LAMP2A acts as a receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy, in which substrate proteins are directly taken up by lysosomes in a manner dependent on ATP and HSPA8/Hsc70.6,9 In this pathway, the cytosolic tail of LAMP2A interacts with HSPA8 and substrate proteins.6,9 Among the three splice variants of human LAMP2, the cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C shows the strongest homology to those of the nematode and fly LAMP orthologs.7 The cytosolic sequences of the nematode and fly LAMP orthologs also bind to RNA.7 The cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C is completely conserved among chicken, mouse and human, although those of LAMP2A and LAMP2B are not.8 No LAMP ortholog has to date been found in yeast and plant genomes, suggesting that RNautophagy is an evolutionarily conserved system in Metazoa.

In our previous study, we have found that the cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C interacts not only with RNA-binding proteins, but also with a variety of DNA-binding proteins.7 Therefore, we assumed that the cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C can also directly bind to DNA, and that DNA can be directly taken up by lysosomes.

Results

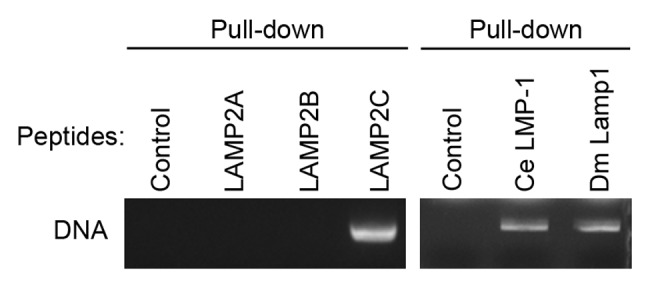

To test for a direct interaction between DNA and the cytosolic sequence of LAMP2C, a pull-down assay was performed using purified plasmid DNA and peptide constructs containing the cytosolic sequence of each LAMP2 variant.7,10 As a result, DNA bound specifically to the LAMP2C peptide (Fig. 1). No interaction with DNA was observed for LAMP2A and LAMP2B peptides.

Figure 1. Interactions of DNA with cytosolic sequences of LAMPs. Interactions of purified plasmid DNA (pCI-neo) with cytosolic sequences of human LAMP2s, nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans) LMP-1, and fly (Drosophila melanogaster) Lamp1. Pull-down assays were performed using 5 μg of DNA and 8 nmol of peptide constructs of cytosolic sequences corresponding to each LAMP, fused to biotin. DNA was detected with EtBr.

The cytosolic sequences of the nematode and fly LAMP orthologs also bind to RNA.7 Therefore, we analyzed the interactions of the cytosolic sequences of nematode and fly LAMP orthologs with DNA. A pull-down assay revealed that DNA directly binds to the cytosolic sequences of these proteins (Fig. 1), indicating evolutionarily conserved RNA- and DNA-binding abilities of LAMP2C and its orthologs.

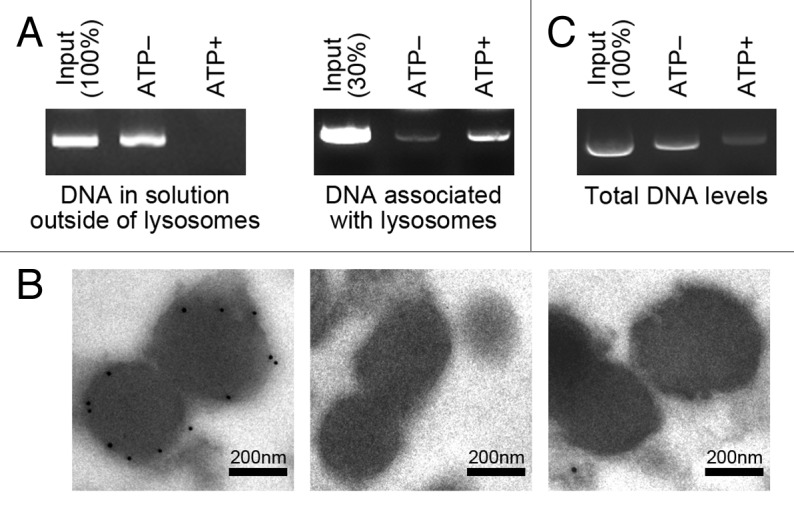

We next analyzed whether DNA can be directly taken up by lysosomes in an ATP-dependent manner. We employed the cell-free system that was used in the identification of RNautophagy.7 Lysosomes were isolated from mouse brain and incubated with purified plasmid DNA, in the presence or absence of ATP. After the incubation, lysosomes and the solution outside of lysosomes were separated by centrifugation and the levels of DNA outside of lysosomes were analyzed. The level of DNA outside of lysosomes was markedly reduced in the presence of ATP (Fig. 2A). In parallel, after the centrifugation, the levels of DNA associated with the precipitated lysosomes (including DNA inside the lysosomes) were analyzed. The level of DNA associated with the lysosomes was higher in the presence of ATP, compared with that in the absence of ATP (Fig. 2A). In addition, we performed immunoelectron microscopy of lysosomes incubated with or without DNA in the presence of ATP. DNA taken up into lysosomes was detected (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that DNA is taken up by lysosomes in an ATP-dependent manner.

Figure 2. Uptake and degradation of DNA by isolated lysosomes. (A) Isolated lysosomes were incubated with 0.5 μg of purified DNA for 5 min in the presence or absence of ATP (energy regenerating system), and pelleted by centrifugation. The levels of DNA remaining in solution outside of lysosomes, and the levels of DNA in the precipitated lysosomes were analyzed. (B) Isolated lysosomes were incubated with or without DNA for 5 min in the presence of ATP (energy regenerating system), and then immunogold labeling was performed using an anti-DNA antibody followed by anti-mouse IgG coupled with 10 nm of gold particles (left and middle, respectively). As a control assay, immunogold labeling was performed without primary antibody (right). Gold particles are observed in the lysosomes in the left panel, while no gold particles are observed in the lysosomes in the middle and the right panels. (C) Isolated lysosomes were incubated with 1 μg of purified DNA for 5 min in the presence or absence of ATP (energy regenerating system), and total levels of DNA in the incubated samples were analyzed.

We next analyzed degradation of DNA in lysosomes. DNA was incubated with isolated lysosomes in the presence or absence of ATP, and the overall levels of DNA in the samples were analyzed. The overall level of DNA was markedly reduced in the presence of ATP (Fig. 2C), indicating ATP-dependent degradation of DNA by isolated lysosomes. Taken together, these observations show an autophagic pathway in which DNA is directly taken up by lysosomes in an ATP-dependent manner and degraded. Hereinafter, we refer to this pathway as DNautophagy.

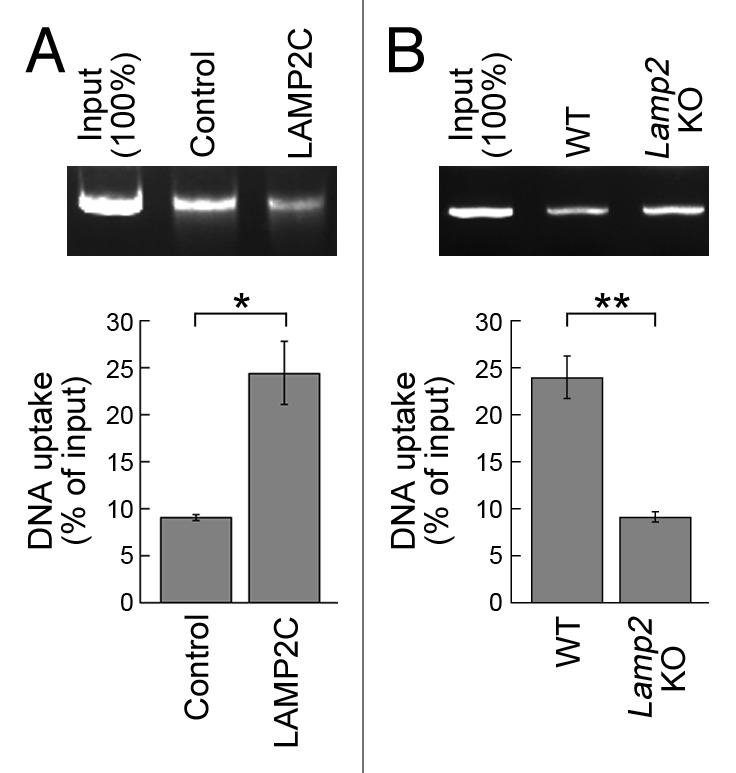

To examine whether LAMP2C functions as a receptor for DNautophagy, we examined the effect of LAMP2C overexpression in this pathway. Lysosomes were isolated from HeLa cells overexpressing LAMP2C or from control cells, and the levels of DNautophagy were measured. Lysosomes derived from LAMP2C-overexpressing cells exhibited increased levels of DNautophagy compared with those isolated from control cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the level of DNautophagy was reduced in lysosomes isolated from LAMP2-deficient mice11 (Fig. 3B). Collectively, our data indicate that LAMP2C functions as a receptor for DNautophagy, in addition to RNautophagy.

Figure 3. Effects of overexpression of LAMP2C and knockout of Lamp2 on DNautophagy. (A and B) Uptake of DNA by lysosomes isolated from HeLa cells transfected with LAMP2C expression vector or empty vector (n = 3) (A). Uptake of DNA by lysosomes isolated from the brains of wild-type and lamp2 knockout mice (n = 3) (B). Isolated lysosomes were incubated with purified DNA for 5 min in the presence of ATP (energy regenerating system). Levels of DNA uptake were measured by subtracting the levels of DNA remaining in solution outside of lysosomes from the levels of input DNA. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively (Student’s t-test).

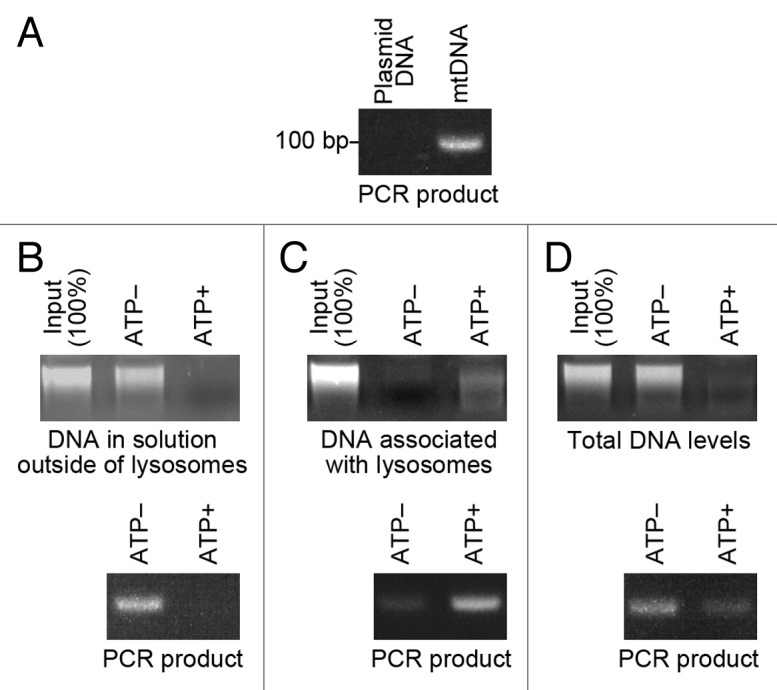

We tested whether endogenous DNA is also degraded by DNautophagy. We used mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) as an endogenous DNA, because mtDNA is known to be released into the cytoplasm upon severe stress.12 mtDNA was isolated from HeLa cells (Fig. 4A). Isolated lysosomes were incubated with isolated mtDNA, in the presence or absence of ATP. Then, the levels of mtDNA outside of and associated with lysosomes, and the overall level of mtDNA were analyzed. The level of mtDNA outside of lysosomes was remarkably reduced in the presence of ATP (Fig. 4B). In parallel, the level of mtDNA in the precipitated lysosomes was higher in the presence of ATP than in the absence of ATP (Fig. 4C). The overall level of mtDNA was notably reduced in the presence of ATP (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that mtDNA can be degraded by DNautophagy.

Figure 4. Uptake and degradation of mtDNA by isolated lysosomes. (A) mtDNA was isolated from HeLa cells. The mtDNA was confirmed by PCR (25 cycles) using primers specific for mtDNA. As a negative control, plasmid DNA (pCI-neo) was used as a template. (B and C) Isolated lysosomes were incubated with 0.5 μg of isolated mtDNA for 5 min in the presence or absence of ATP (energy regenerating system), and pelleted by centrifugation. The levels of DNA remaining in solution outside of lysosomes (B), and the levels of DNA in the precipitated lysosomes were analyzed (C). The mtDNA in the samples was confirmed by PCR using primers specific for mtDNA. (D) Isolated lysosomes were incubated with 0.5 μg of mtDNA for 5 min in the presence or absence of ATP (energy regenerating system), and total levels of DNA in the incubated samples were analyzed. The mtDNA in the samples was confirmed by PCR.

Discussion

Together with the findings of our previous study,7 we have shown that lysosomes can directly uptake and degrade both RNA and DNA in an ATP-dependent manner, and that LAMP2C functions as a receptor for these pathways. Nematode and fly LAMP orthologs also bind to RNA and DNA, suggesting that RNautophagy and DNautophagy are evolutionarily conserved systems in Metazoa. The adenosine triphosphatases involved in these pathways remain elusive. Because RNautophagy and DNautophagy were not completely abolished in lysosomes derived from LAMP2-deficient mice7 (Fig. 3B), we cannot rule out the possibility of LAMP2-independent pathway(s) operating in RNautophagy and DNautophagy. Further studies are needed to clarify these points.

The physiological significance of DNautophagy remains largely obscure. Endogenous DNAs could be an attractive target for future studies on DNautophagy. The ability of isolated lysosomes to incorporate mtDNA suggests that this molecule could be a substrate in vivo. We assume that DNautophagy may also play an important role in the maintenance and quality control of cells and tissues through the lysosomal uptake of mtDNA. mtDNA contains unmethylated CpG motifs, and induces inflammation when released into the cytosol or extracellular space. In heart, deletion of lysosomal deoxyribonuclease II leads to inflammation and cardiomyopathy caused by cell-autonomous detection of mtDNA by TLR9.13 mtDNA released into the circulation also causes inflammation through TLR9.14 It is of interest that most tissues expressing LAMP2C at a notable level in mice were energy-consuming tissues such as brain, heart, skeletal muscle, liver and kidney.7 DNautophagy might be working in response to cytosolic release of mtDNA in these tissues.

To our knowledge, RNautophagy and DNautophagy are the first pathways identified to selectively deliver nucleic acids into lysosomes. It is well known that mRNA can be degraded by exonucleases in the cytoplasm and nucleus.15 However, lysosomes contain various endonucleases and exonucleases, and thus, are thought to play an important role in the degradation of nucleic acids. DNautophagy and RNautophagy likely contribute to the metabolism and homeostasis of nucleic acids. Indeed, significant accumulation of RNA was observed in the brains of LAMP2-deficient mice.7 Because macroautophagy mediates the bulk degradation of cytoplasmic components, cytoplasmic nucleic acids can also be degraded by macroautophagy. A recent study has shown that loss of the zebrafish ortholog of RNASET2, a lysosomal RNase, results in accumulation of undigested rRNA within lysosomes in neurons of the brain, and causes white matter lesions.16 These observations indicate that a significant amount of rRNA is degraded in lysosomes, and that the degradation of rRNA in lysosomes is essential for homeostasis of neurons. Considering the high expression level of Lamp2c in neurons,7 we assume that RNAs, including rRNA, can be imported into lysosomes by RNautophagy in neurons. Another pathway that could transport rRNA into lysosomes is ribophagy, a macroautophagic pathway targeting ribosomes.17 It is possible that multiple systems for nucleic acid degradation may function coordinately, although there may be a division of roles among systems. The relationship between DNautopagy or RNautophagy and other degradation systems for nucleic acids is an interesting issue.

Another possible role for DNautophagy and RNautophagy in vivo is entrapment of exogenous nucleic acids such as viral RNA and DNA into lysosomes/endosomes, leading to the initiation of immune responses by toll-like receptors (TLRs).18-21 Intriguingly, all TLRs that recognize RNA or DNA localize to the lysosomal/endosomal membrane, whereas other TLRs are found at the plasma membrane.22 The nucleic acid-binding sites of lysosomal/endosomal TLRs are located in the luminal region of lysosomes/endosomes,22,23 and translocation of viral RNA or DNA to lysosomes/endosomes is likely to be necessary for inducing a lysosomal/endosomal TLR-mediated innate immune response. We suppose that lysosomal uptake of viral nucleic acids in the cytoplasm by RNautophagy and DNautophagy may play an important role in the initiation of antiviral immune responses in certain types of cells. Interestingly, LAMP2A, another isoform of LAMP2 known to be a receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy,9,24 has been reported to facilitate major histocompatibility complex class II antigen presentation.25 In plasmacytoid dendritic cells engulfing DNA-containing immune complexes, MAP1LC3A-associated phagocytosis is required to initiate the interferon pathway.26 MAP1LC3A-associated phagocytosis of DNA-immune complexes recruits LAMP2 to phagosomes.26 It may be possible that DNautophagy is involved in this system. The possible involvement of DNautophagy and RNautophagy in the immune system remains to be studied.

Materials and Methods

Peptides

Biotin-conjugated peptides were prepared as described previously.7,10 The sequences of the peptides containing the cytosolic sequence of human LAMP2s, C. elegans LMP-1 or Drosophila Lamp1 are as follows. human LAMP2A: [Biotin]-GSGSGSGSGSIGLKHHHAGYEQF; human LAMP2B: [Biotin]-GSGSGSGSGSIGRRKSYAGYQTL; human LAMP2C: [Biotin]-GSGSGSGSGSIGRRKSRTGYQSV; C. elegans: [Biotin]-GSRARAKRQGYASV; Drosophila: [Biotin]-GSRRRSTSRGYMSF; Control peptide: [Biotin]-GSGSGSGSGS.

Plasmids, cell culture and transfection

pCI-neo-Lamp2c plasmid was prepared as described previously.7 HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, 12701-017) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cell Culture Bioscience, 171012). Transient transfection with each plasmid was performed using Lipofectamine LTX with Plus Reagent (Invitrogen, 15338-100), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

LAMP2-deficient mice

LAMP2-deficient mice, which lack expression of all isoforms of LAMP2,11 were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for more than 17 generations. These mice were propagated at the National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry. All animal experiments were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines of the National Institute of Neuroscience, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, and were approved by the Animal Investigation Committee of the Institute.

Pull-down assay

Pull-down assays were performed as previously described.7 Streptavidin–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare, 17-5113-01) were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin for 15 h. Five micrograms of purified plasmid DNA (pCI-neo, Promega, E1841) was incubated with 8 nmol of biotin fusion peptides and 40 μl of the beads in PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100. After 2 h of incubation at 4°C, beads were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100. DNA pulled down with the beads was extracted using phenol-chloroform, and analyzed by electrophoresis in agarose gels containing ethidium bromide.

Isolation of mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA was isolated from HeLa cells using a Mitochondrial DNA Isolation Kit (BioVision, K280-50) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. mtDNA was confirmed by PCR using Ex Taq polymerase (TAKARA, RR001) according to a standard method. The primers used for the detection of human mtDNA are as follows: 5′-ATG CTA AGT TAG CTT TAC AG-3′ and 5′-ACA GTT TCA TGC CCA TCG TC-3′.27

Uptake and degradation of DNA by isolated lysosomes

Isolation of lysosomes was performed as previously described.7 Briefly, lysosomes were isolated from 10- to 12-week-old mouse brains using a Lysosome Enrichment Kit (Pierce, 89839).

For monitoring DNA uptake, isolated lysosomes (25 to 50 μg of protein) were incubated with 0.5 μg of purified plasmid DNA (pCI-neo) or isolated mtDNA at 37°C for 5 min in 30 μl of 0.3 M sucrose containing 10 mM MOPS buffer (pH 8.0) with or without energy regenerating system (ATP− or ATP+) (10 mM ATP, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM phosphocreatine, and 50 μg/ml creatine phosphokinase). After the incubation, lysosomes were precipitated by centrifugation and DNA remaining in the supernatant was analyzed by electrophoresis in agarose gels containing ethidium bromide. In parallel, after the centrifugation, the levels of DNA associated with the precipitated lysosomes (including DNA inside the lysosomes) were analyzed. DNA in agarose gels was detected using FluorChem (Alpha Innotech), and the levels of DNA were quantified by densitometry using FluorChem software (Alpha Innotech). The mtDNA in the samples was confirmed by PCR using primers specific for mtDNA.

Degradation of DNA by isolated lysosomes was investigated as follows. Isolated lysosomes and 1 μg of purified plasmid DNA (pCI-neo) or 0.5 μg of isolated mtDNA were incubated with or without energy regenerating system for 5 min, and the total levels of DNA in the samples were analyzed. The mtDNA in the samples was confirmed by PCR.

For assays using HeLa cells, lysosomes were isolated from ~7.0 × 107 cells transfected with pCI-neo-Lamp2c or empty vector, and subjected to analysis as described above.

Electron microscopy

For immunogold electron microscopy, isolated lysosomes were incubated with or without purified plasmid DNA (pCI-neo) in the presence of ATP (energy regenerating system) for 5 min, precipitated by centrifugation, and fixed in 0.1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 16 h at 4°C. Samples were then dehydrated in a series of water/ethanol mixtures to 100% ethanol, and embedded in LR White (Nisshin EM Co., Ltd., 3962). The embedded samples were sectioned at 100 nm, and collected on 400-mesh nickel grids. Immunogold labeling was performed using an anti-DNA antibody (1:1000, Abcam, ab27156) followed by anti-mouse IgG coupled with 10 nm of gold particles, and viewed using a Tecnai Spirit transmission electron microscope (FEI), at 80 kV.

Statistical analyses

For comparisons between two groups, the statistical significance of differences was determined by Student’s t-test. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiromi Fujita, Yoshiko Hara and Noriko Shikama for technical assistance, Dr. Hirohiko Hohjoh for helpful discussions, and Drs. Judith Blanz and Paul Saftig for the LAMP2-deficient mice. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) (24680038 to T.K.) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (to K.W.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; and partly by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (22790838 to T.K.) and Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Nervous and Mental Disorders from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare of Japan (21-9, 23-1 and 24-11 to T.K.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- LAMP

lysosomal-associated membrane protein

- HSPA8

heat shock 70-kD protein 8

- Hsc70

70-kD heat shock cognate protein

- MAP1LC3A/LC3A

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/24880

References

- 1.De Duve C, Pressman BC, Gianetto R, Wattiaux R, Appelmans F. Tissue fractionation studies. 6. Intracellular distribution patterns of enzymes in rat-liver tissue. Biochem J. 1955;60:604–17. doi: 10.1042/bj0600604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novikoff AB, Beaufay H, De Duve C. Electron microscopy of lysosomerich fractions from rat liver. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1956;2(Suppl):179–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.2.4.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 2011;147:728–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansen T, Lamark T. Selective autophagy mediated by autophagic adapter proteins. Autophagy. 2011;7:279–96. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahu R, Kaushik S, Clement CC, Cannizzo ES, Scharf B, Follenzi A, et al. Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell. 2011;20:131–9. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dice JF. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2007;3:295–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujiwara Y, Furuta A, Kikuchi H, Aizawa S, Hatanaka Y, Konya C, et al. Discovery of a novel type of autophagy targeting RNA. Autophagy. 2013;9:403–9. doi: 10.4161/auto.23002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eskelinen EL, Cuervo AM, Taylor MR, Nishino I, Blum JS, Dice JF, et al. Unifying nomenclature for the isoforms of the lysosomal membrane protein LAMP-2. Traffic. 2005;6:1058–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science. 1996;273:501–3. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kabuta T, Furuta A, Aoki S, Furuta K, Wada K. Aberrant interaction between Parkinson disease-associated mutant UCH-L1 and the lysosomal receptor for chaperone-mediated autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23731–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801918200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka Y, Guhde G, Suter A, Eskelinen EL, Hartmann D, Lüllmann-Rauch R, et al. Accumulation of autophagic vacuoles and cardiomyopathy in LAMP-2-deficient mice. Nature. 2000;406:902–6. doi: 10.1038/35022595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222–30. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oka T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Taneike M, Takeda T, Tamai T, et al. Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature. 2012;485:251–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houseley J, Tollervey D. The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell. 2009;136:763–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haud N, Kara F, Diekmann S, Henneke M, Willer JR, Hillwig MS, et al. rnaset2 mutant zebrafish model familial cystic leukoencephalopathy and reveal a role for RNase T2 in degrading ribosomal RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1099–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009811107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kraft C, Deplazes A, Sohrmann M, Peter M. Mature ribosomes are selectively degraded upon starvation by an autophagy pathway requiring the Ubp3p/Bre5p ubiquitin protease. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:602–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Kaisho T, Sato S, Sanjo H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–5. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–8. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, Ampenberger F, Kirschning C, Akira S, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takeda K, Akira S. Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crozat K, Beutler B. TLR7: A new sensor of viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6835–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401347101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. Unique properties of lamp2a compared to other lamp2 isoforms. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:4441–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou D, Li P, Lin Y, Lott JM, Hislop AD, Canaday DH, et al. Lamp-2a facilitates MHC class II presentation of cytoplasmic antigens. Immunity. 2005;22:571–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henault J, Martinez J, Riggs JM, Tian J, Mehta P, Clarke L, et al. Noncanonical autophagy is required for type I interferon secretion in response to DNA-immune complexes. Immunity. 2012;37:986–97. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wrischnik LA, Higuchi RG, Stoneking M, Erlich HA, Arnheim N, Wilson AC. Length mutations in human mitochondrial DNA: direct sequencing of enzymatically amplified DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:529–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]