Abstract

Background

There are few effective smoking cessation interventions for adolescent smokers. We developed a novel intervention to motivate tobacco use behavior change by 1) enhancing desire to quit through the use of abstinence-contingent incentives (CM), 2) increasing cessation skills through the use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and 3) removing cessation barriers through delivery within high schools.

Methods

An exploratory four-week, randomized controlled trial was conducted in Connecticut high schools to dismantle the independent and combined effects of CM and CBT; smokers received CM alone, CBT alone, or CM+CBT. Participants included 82 adolescent smokers seeking smoking cessation treatment. The primary outcome was seven-day end-of-treatment (EOT) point prevalence (PP) abstinence, determined using self-reports confirmed using urine cotinine levels. Secondary outcomes included one-day EOT PP abstinence and cigarette use during treatment and follow up.

Results

Among participants who initiated treatment (n=72), group differences in seven-day EOT-PP abstinence were observed (χ2=10.48, p<0.01) with higher abstinence in the CM+CBT (36.7%) and CM (36.3%) conditions when compared with CBT (0%). One-day EOT-PP abstinence evidenced similar effects (χ2= 10·39, p<0·01; CM+CBT: 43%, CM: 43%, CBT: 4·3%). Survival analyses indicated differences in time to first cigarette during treatment (χ2=8·73, p =·003; CBT: Day 3, CM: Day 9, CM+CBT: Day 20). At one-and three-month follow ups, while no differences were observed, the CM alone group had the slowest increase in cigarette use.

Conclusions

High-school, incentive-based smoking cessation interventions produce high rates of short-term abstinence among adolescent smokers; adding cognitive behavioral therapy does not appear to further enhance outcomes.

Keywords: Adolescents, smoking cessation, tobacco, contingency management, incentives, cognitive behavioral therapy

1. INTRODUCTION

Tobacco smoking, a leading preventable cause of premature death in the United States and worldwide, is a pediatric disease (Kessler et al., 1997). The majority of adult smokers start smoking during adolescence (Centers for Disease Control, 2001). Current estimates indicate that in the United States alone around 2·6 million adolescents are current tobacco users and that more than one-fifth of adolescents are smokers by the time they leave high school (Centers for Disease Control, 2010). There is an imperative need for targeted interventions that can be applied prior to the establishment of entrenched, lifelong patterns of tobacco use and other negative health outcomes. Among adolescent smokers, a significant number (61%; Centers for Disease Control, 2001) indicate interest in quitting smoking and report having made a quit attempt in the past 12 months, but success rates are low (between 7–12%; Grimshaw and Stanton, 2006; Sussman, 2002). Existing behavioral and pharmacological smoking cessation treatments for adolescents have had limited success (Grimshaw and Stanton, 2006; Sussman, 2002). Effective methods based on a developmental understanding of adolescence are urgently needed.

Emerging neurobiological evidence suggests that adolescence is associated with heightened sensitivity to behaviors driven by emotions and rewards (Somerville et al., 2010). Of significance, behavioral interventions that provide performance-contingent rewards have been used to motivate change in academic performance and other behaviors in adolescents (Eisenberger and Rhoades, 2001; Gottfried, 1985; Pintrich and De Groot, 1990). Among adult substance users, incentive-based interventions (also called contingency management or CM) have demonstrated efficacy reducing use of many substances including tobacco (Higgins et al., 2008; Petry and Simcic, 2002; Volpp et al., 2009; Higgins et al., 2004; Tidey, 2012, Sigmon and Patrick, 2012). Based on operant behavior reshaping concepts, these interventions follow two simple principles: first, that substance use is maintained by the reinforcing effects of the drug, and second, that substance use can be decreased by the availability of alternative, non-drug reinforcers.

If adolescents are indeed more sensitive to rewards, they may be responsive to the use of CM interventions to motivate change in substance use behaviors (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2008; Richards et al., 2012; Stanger and Budney, 2010). Emerging evidence supports the use of such interventions for adolescent smoking cessation (Corby et al., 2000; Gray et al., 2011, Weissman et al., 1987; Roll, 2005; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2006; Cavallo et al., 2007). However, implementation of such interventions is challenging due to the need for rapid, accurate monitoring of tobacco use and immediate delivery of rewards for abstinence. To address these challenges, we developed a novel smoking cessation intervention for adolescents that provided reinforcement for abstinence, and enhanced its feasibility through delivery in local high schools, and use of once-daily urine cotinine to monitor tobacco use (Schepis et al., 2008). We also sought to enhance the durability of effects by combining it with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) (McDonald et al., 2003). Two pilot studies yielded robust end-of-treatment abstinence rates (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2006; Cavallo et al., 2007), but they were small trials and it was not possible to attribute changes to CM, CBT, or the combination. Thus, in the current study, we conducted the first randomized controlled trial that explored the independent and combined efficacy of CM and CBT for adolescent smoking cessation. We hypothesized that the combined use of CM for abstinence and CBT would result in better end-of-treatment (EOT) abstinence rates and through a one- and three-month follow up than either condition alone.

2. METHODS

This was a single center, randomized, parallel group study with three treatment conditions: CM alone, CBT alone and CM+CBT. Urn randomization was used to balance the groups on gender and race. The intervention was four weeks in duration based on our published pilot studies (Krishnan-Sarin et al,, 2006; Cavallo et al., 2007) and findings (unpublished) from a pilot eight week trial where we observed very high rates of drop out after the first four weeks.

2.1. Participants

Treatment-seeking adolescent smokers recruited from local Connecticut high schools during academic years 2008–2009 and 2009–2010. The study protocol was approved by the Yale School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee and by the local school boards. Information sheets detailing the intervention were mailed out to all parents in the participating schools prior to the beginning of each academic year. Parents were told that if their child was a smoker they (the child) would have the option of participating in the research intervention, and if they (the parent) did not want their child to participate they needed to call and inform the schools; active parental consent was not required. Interested adolescents could either sign up at recruitment tables (set up at lunch periods or during home rooms) or privately by calling the researchers or entering their information on sign up cards maintained in locked boxes at the school. Interested adolescents, who were not denied permission to participate by parents, were scheduled for an initial screening appointment at the local school where assent was obtained from adolescents aged 14–17, and consent was obtained from those aged 18 or older.

Adolescents were included if they reported smoking at least five cigarettes per day for the past six months and had quantitative urine cotinine levels of 350 ng/ml or higher (Graham Massey Analytical Labs, Shelton, CT); these criteria were chosen in order to ensure that participants were regular smokers. The Diagnostic Predictive Scale (DPS; Lucas et al., 2001) and an evaluation by a clinical psychologist were used to exclude those with any current DSM-IV Axis I disorders (including any other current substance dependence disorder other than Nicotine Dependence), any significant current untreated medical condition, or current suicidal/homicidal risk.

2.2. Interventions

All interventions were manual-guided and supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist based on our previous work (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2006; Cavallo et al., 2007). Eligible adolescents scheduled a quit date and received a 45-minute “preparation to quit” session, 4 to 7 days prior to their quit date, during which motivational and cognitive behavioral strategies were used to emphasize the risks of continued smoking and the benefits of quitting, as well as teach strategies to initiate cigarette abstinence. At the end of this session, adolescents were randomly assigned using a computer generated randomization list to receive one of three treatment conditions for the remaining four week treatment period: CBT alone, CM alone, or CBT+CM.

2.2.1. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Participants in this condition participated in CBT sessions (approximately 30 minutes in duration) starting on their quit day and continuing weekly for the remaining treatment period. Overall, participants were taught self-control strategies to avoid tobacco use as well as identify high-risk situations and use coping skills including problem solving, peer refusal skills, stress reduction, obtaining social support, and relapse prevention.

Five counselors (two with bachelors’ degrees in psychology and four years of experience providing smoking cessation counseling to adolescents and three with doctoral degrees in clinical psychology) provided CBT. All counselors were trained on the manual-guided CBT by a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive experience in smoking cessation (JLC), and participated in weekly supervision to discuss cases with a supervisor (JLC and DC) and maintain adherence to manual guidelines.

2.2.2. Contingency Management (CM) for abstinence

CM appointments to monitor and reinforce abstinence were initiated on quit day. Abstinence was determined using breath CO levels (< 7 ppm; Vitalograph Breath CO, Bedfont, MA) and semi-quantitative urine cotinine readings [during the first week: less than the level on the earlier day or ≤ level 2 (30–100 ng/ml); during the subsequent weeks: ≤ level 2 (30–100 ng/ml); NicAlert Immunoassay Test Strips; Jant Pharmacal Corporation, Encino, CA], and ascertained once daily in the first two weeks and once every other day during the third and fourth weeks (Schepis et al., 2008).

Participants in the CM condition were reinforced for abstinence on an escalating magnitude schedule of reinforcement with a reset contingency (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2006). Participants were paid $2.00 for the first assessment that was negative, with payments progressively increasing by $1.00 for each subsequent negative assessment. Participants for whom abstinence was not confirmed were not paid for that assessment and had the payment for their next assessment reset back to the initial level of $2.00. Participants in the CM condition could earn up to $262 if they were continuously abstinent after the quit day.

The CM appointments were ten minutes in duration and were conducted by research assistants who were trained (by SKS and DC) to determine abstinence, provide CM payments and check on the participants progress but not provide any smoking cessation counseling. A centralized system including cell phone contact was used to keep track of payments and any deviations/problems were dealt with on an ongoing basis.

2.3. Other Procedures

All weekday appointments (including counseling sessions) were conducted in the school nurse’s office or the school library either after school or during free periods. Participants were not allowed to miss class to participate. Weekend CM appointments were conducted at public locations, including fast food restaurants, libraries, and other sites that were easily accessible to both the participant and research team and where biochemical measurements could be obtained; these appointments were conducted in quiet corners at each location and no information was shared with the proprietors at any locations.

Participants in all three groups were also provided with incentives for completing weekly assessments and attending CBT sessions. Payments for attendance were chosen to ensure fairly equivalent total incentives across groups (and minimize the possibility of differences in outcome being related to incentive amounts) and were as follows: 1) CM alone group: $5 at each weekly appointment for completing assessments, 2) CM + CBT group: $5 at each weekly appointment for completing assessments and $5 for attending CBT sessions, 3) CBT alone group: $20 at each weekly appointment for completing assessments and $20 for attending CBT sessions.

2.4. Outcomes

Self-reports of tobacco (Time Line Follow Back; Sobell et al., 1992) and urine samples for quantitative cotinine assessments (Graham Massey Analytical Labs, Shelton, CT) were collected at weekly assessment sessions. The primary outcome was seven-day point prevalence (PP) abstinence at the end of treatment (EOT) determined by negative self-reports of tobacco use over the past seven days and confirmed by quantitative urine cotinine levels of ≤ 50 ng/ml (SRNT 2002). We also examined one-day EOT PP abstinence and seven-day PP abstinence at one- and three-month follow-up appointments, and various other abstinence outcomes, in accordance with the recommendations of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco (Mermelstein et al., 2002).

2.5. Data analysis

Chi-square analyses and t-tests were used to evaluate baseline differences in participant characteristics and treatment retention rates among those randomized to treatment (n = 82). Outcome analyses were conducted on the following samples: the 82 participants who received the “preparation to quit” session and were randomized to treatment (intention-to-treat sample) and the 72 participants who participated in “quit day” (initiated treatment sample). The results are consistent across analysis samples and only results from the sample that initiated treatment (n=72) are presented. For the primary outcome, chi-square analyses were used to compare the treatment groups on PP abstinence at EOT (seven-day and one-day) and one- and three-month follow ups (seven-day). For these analyses, all participants who dropped out or missed appointments were counted as treatment failures and considered to be smoking. Second, ANOVA models were used to assess differences across conditions on percentage of cotinine-free urines (defined as cotinine ≤ 50 ng/ml) and days abstinent from cigarettes (determined using daily self-reports) during the treatment period. Third, survival analyses evaluated group differences with respect to self-reports of time to first cigarette use during treatment. Finally, changes in self-reports of cigarette use from baseline to end-of-treatment and then to follow ups were modeled using piecewise regression analyses.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant characteristics and retention in treatment

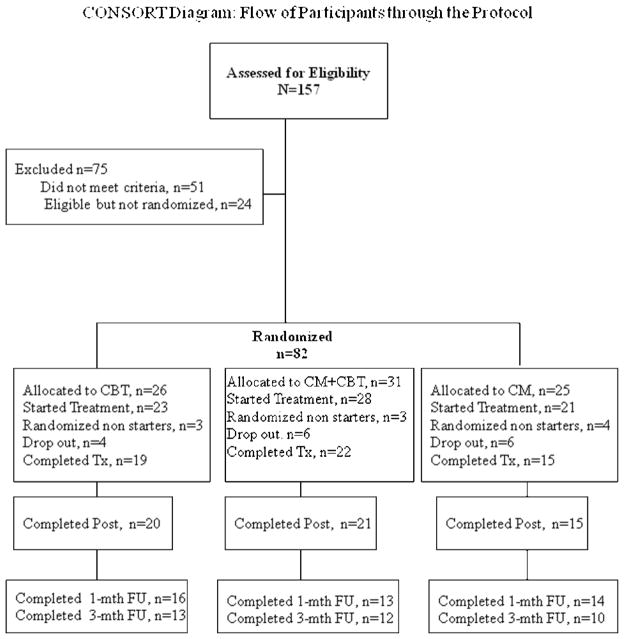

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 157 adolescents were screened for participation in the study. Of these, 106 were eligible for the study; the primary reasons for ineligibility were not meeting the smoking quantity/frequency requirements (n = 35) or meeting criteria for an Axis I DSM-IV disorder (n = 16). Of those who were eligible, 24 participants dropped out and could not be reached, while 82 participants attended their “preparation to quit” session and were randomized to a treatment condition (26 to CBT, 31 to CM + CBT and 25 to CM). The randomized sample consisted of 38 males and 44 females, with an average age of 16·1 (SD=1·8) years, who smoked an average of 14 (SD=5·2) cigarettes/day, with baseline urine cotinine of 1091 (SD=205) ng/ml and average modified Fagerstrom scores (Prokhorov et al., 1996) of 5·4 (SD=1·8) indicating a moderate level of dependence; there were no significant differences between the three treatment conditions on these baseline variables.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram: Flow of Participants through the Protocol

Of these 82 participants, 72 attended their scheduled quit date (23 CBT, 28 CM+ CBT and 21 CM). There were no statistically significant differences in retention by condition (number of CBT sessions, CM appointments, or weekly attendance). Adolescents receiving CBT attended an average of 4·5 (SD = 1·0) out of 5 sessions and the average length of the CBT session was 30·7 minutes (SD = 5·2). Eighteen participants dropped out of the study after start of treatment; 4 in the CBT condition, 6 in the CM + CBT condition and 6 in the CM alone condition. There were no statistically significant differences in the number of follow up appointments completed by treatment condition. Follow-up rates were at 62% at one-month (16 CBT, 13 CM+CBT, 14 CM) and 49% at three-months (13 CBT, 12 CM+CBT, 10 CM).

3.2. Outcomes by treatment condition

For the participants who initiated treatment (n=72), significant differences were observed between the three treatment conditions on seven-day EOT PP abstinence (χ2=10·5, p<0.01) with higher rates in the CM+CBT (36·7%) and CM (36·3%) conditions when compared with CBT (0%). One-day EOT PP abstinence was also significantly different (χ2= 10·4, p<0.01) with higher rates in the CM+CBT (43%) and CM (43%) conditions compared with CBT (4·3%). There were no significant differences between seven-day PP abstinence at one-month (CM+CBT: 20%; CM: 7.1% and CBT: 4.3%; χ2=3·05, p=0·22) and three-month (CM+CBT: 7·1%; CM: 7·1% and CBT: 0%; χ2=1·64, p=0·44) follow up appointments.

Table 1 presents other self-report and biochemical outcomes from the weekly appointments and the results indicate that during the four-week treatment period there were significant differences in daily cotinine-free urines, and self-reports of percent days abstinent, with post hoc analyses showing higher rates in the CM+CBT and CM conditions when compared with CBT. There were no significant differences between the CM+CBT and CM conditions.

Table 1.

Comparison of primary outcomes by treatment condition determined at weekly counseling appointments (unless indicated otherwise) over the treatment period

| CBT | CM+CBT | CM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | F | p | Post Hoc | df |

| Number of urine specimens submitted | 4.30 | 1.26 | 4.21 | 1.42 | 4.14 | 1.26 | 1.26 | .92 | ns | 1,69 |

| Number of urines with cotinine ≤ 50 ng/ml | 0.43 | 0.95 | 1.82 | 1.81 | 1.76 | 1.81 | 5.77 | .01 | CM>CBT, CM+CBT>CBT | 1,69 |

| % urines with cotinine ≤ 50 ng/ml | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 5.96 | .00 | CM>CBT, CM+CBT>CBT | 1,69 |

| % of past 28 days abstinent from cigarettes, self report | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.88 | 0.18 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 7.80 | .00 | CM>CBT, CM+CBT>CBT | 1,65 |

CBT=Cognitive behavioral therapy, CM=Contingency management, ns= not signficant

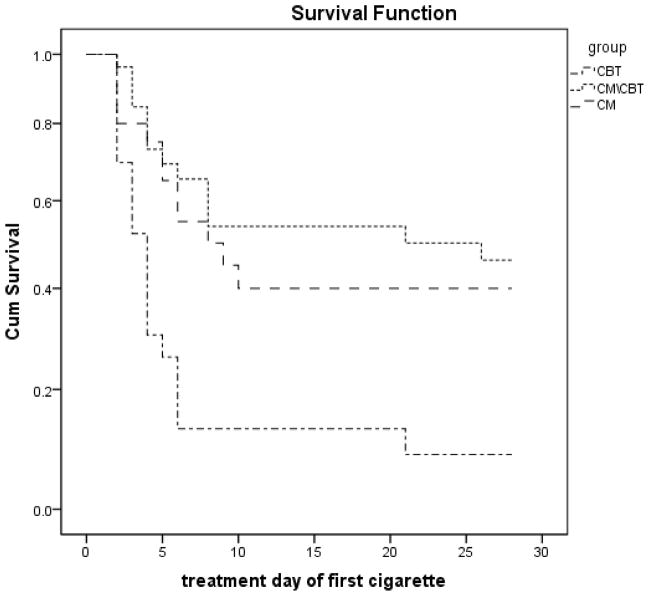

The survival analysis indicated a significant difference in days to first cigarette use by treatment condition, with CBT participants initiating use at day 3, CM at day 9, and CM+CBT at day 20 (χ2 = 8·73, p = ·003; See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival curves for treatment groups during treatment period following quit date

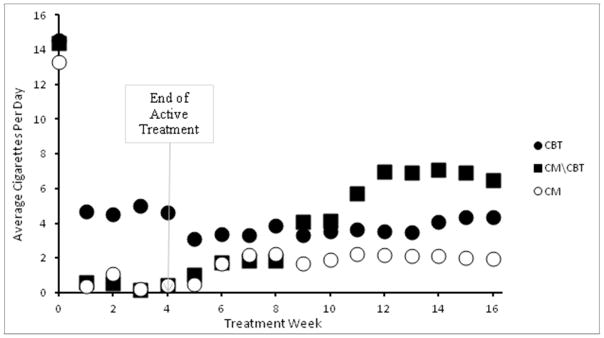

In the piecewise regression model there was an overall reduction in cigarette use (slope F = 191·64, p < ·001), a main effect of phase, (F= 127·97, p < ·001) indicating that the intercept for the active treatment was significantly higher than the intercept for follow ups, and a “slope X phase” interaction (F = 280·8, p = ·00) indicating a greater rate of change (slope) during the active treatment phase compared to the follow up phase. Finally, there was a “group X slope X phase” interaction (F = 4·38, p = ·01) indicating that the groups with the greater slopes in active treatment did not have the greatest slopes in follow up. These findings were consistent with plots of the raw data, which are shown in Figure 3. Both the piecewise regression and the raw data suggest that cigarette use decreased sharply during treatment. There was some increase in cigarette use after treatment ended, but the rate of increase was smallest among participants assigned to CM.

Figure 3.

Cigarette use among participants in the three treatment groups starting on quit day nd through the treatment period (weeks 0–4) and follow-up period (weeks 5–16). Raw values; mean days of cigarette use by group by week. Note that n’s differ over time (72 started Quit Day at week 0, 56 at week 4, 35 at week 16).

4. DISCUSSION

This study was the first to evaluate a novel high school-based smoking cessation intervention for adolescent smokers and compare the independent and combined effects of the two components of the intervention, namely, use of incentives contingent on tobacco abstinence (CM) and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The results which provide partial support for our a priori hypothesis, suggest that CM for abstinence when used alone, or in combination with CBT, resulted in greater abstinence when compared with CBT alone. Importantly, the abstinence rates in those receiving CM were much higher (36%- 43%) than those observed for existing adolescent smoking cessation interventions (7% to 12%; Sussman, 2002) and were based on stringent criterion of self-reports confirmed by biochemical levels. These results support the concept that provision of rewards contingent on tobacco abstinence can be a powerful tool for promoting tobacco abstinence in adolescents. Adolescence has been shown to be associated with enhanced sensitivity to rewards (Somerville et al., 2010), including nicotine (Elliott et al., 2005), and one way altering use of substances may be by replacing the substance of choice (in this case tobacco) with alternative rewards that are equally or more rewarding. Our results suggest that adolescents are sensitive to such operant reshaping and that monetary incentives can be used to motivate changes in tobacco use behaviors.

Interestingly, we observed no impact of CBT when provided alone or in combination with CM, which is contrary to the existing literature that points to the efficacy of CBT for smoking cessation in adolescents (McDonald et al., 2003). These results raise the possibility that during the initial phase of a quit smoking attempt, when adolescents are not only trying to focus on quitting but are also experiencing nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Smith et al., 2008), they may find it easier to focus on simpler extrinsic reinforcement outcomes like “quit and get rewards” and may have more difficulty with learning more complex skills focused on more intrinsic issues. CBT skills are cognitively complex and demanding and hence may take longer to learn and implement; our intervention duration of four weeks may not have been long enough to observe the emergent influence of these skills. However, the combined intervention group had a significantly longer time to first lapse, suggesting that perhaps the behavioral support from the counselors providing the CBT, in combination with the motivation provided by the abstinent contingent incentives, kept the adolescents smoke-free for longer periods of time. It is also possible that the superiority of CM over CBT may be related to the frequency of contact and monitoring in the CM conditions rather than the incentives. Future studies might focus on the short- and long-term impact of treatments like CBT and how they can be optimally combined with CM for adolescents smoking cessation.

The follow-up rates suggest that while many of the adolescents who quit during the treatment period returned to smoking, the CM alone group had lower rates of cigarette use. However, this observation is limited by the comparatively low rate of follow-up, with differential rates of missing data by condition. Although the piecewise regression reduced, to some extent, the issues associated with case-wise deletion by interpolating missing values, we cannot dismiss the possibility of bias. Future research needs to focus on developing methods to extend the short-term benefits and durability of incentive-based interventions. This could be achieved through the use of continued rewards for tobacco abstinence or uptake of other pro-social substitution behaviors that are known to be protective against tobacco use such as increased physical activity and sports participation (Audrain-McGovern et al., 2012; Hedman et al., 2007; Rainey et al., 1996), participation in school clubs (Elder et al., 2000 ) or religious organizations (Piko and Fitzpatrick, 2004) and getting good grades (Ellickson et al., 2008). Durability and efficacy of such interventions could also be enhanced by the use of adjunctive behavioral therapies focused on addressing predictors of treatment failure such as impulsivity (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2006) or response to stress (Schepis et al., 2011). Adjunctive use of pharmacological therapies may also enhance efficacy; for example, ongoing work by our group is examining the feasibility and efficacy of the adjunctive use of nicotine patch therapy with incentives and CBT to promote smoking cessation in high school smokers.

In summary, the results of this trial suggest that the use of abstinent-contingent rewards can be a powerful tool for achieving tobacco abstinence in treatment-seeking adolescent smokers and suggest that in this context, the addition of CBT provides minimal additional short-term benefit in abstinence rates. The significance of our findings is enhanced by the use of manual-guided principles and high school settings which may have facilitated high abstinence rates by not only enhancing the feasibility of providing the intervention, but also reducing the burden on the adolescents and making it easy for them to access the intervention if and when they desire to quit smoking. However, as discussed above, our study has important limitations, including a small sample size and low follow up rates and, therefore, the results need to be interpreted with caution. Future studies with larger samples need to replicate these findings. Provided these results are replicated in larger trials, future work also needs to focus on developing community funding and support for such interventions, methods to implement and disseminate the use of these interventions in high school settings, and to develop the use of alternative rewards, perhaps related to school performance, for tobacco abstinence. The development and dissemination of such smoking cessation interventions could represent a significant step towards reducing the burden of tobacco use during adolescence.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant P50DA009241; the NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication

Footnotes

Contributors

Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin was responsible for the design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Bruce Rounsaville contributed to the design of the study. Kathleen Carroll, Judith Cooney, Dana Cavallo and Thomas McMahon contributed to the design of the study and interpretation of the results. Dana Cavallo and Judith Cooney supervised and provided the interventions. Ty Schepis, Grace Kong, Thomas Liss and Amanda Liss provided the interventions. Charla Nich and Theresa Babuscio managed the data and conducted data analyses. All authors (except Dr. Rounsaville) contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Audrain-McGovern JD, Rodriguez D, Rodgers K, Cuevas J, Sass J. Longitudinal variation in adolescent physical activity patterns and emergence of tobacco use. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37:622–633. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo DA, Cooney JL, Duhig AM, Smith AE, Liss TB, McFetridge AK, Krishnan-Sarin S. Combining cognitive behavioral therapy with contingency management for smoking cessation in adolescent smokers: a preliminary comparison of two different CBT formats. Am J Addict. 2007;16:468–474. doi: 10.1080/10550490701641173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control Surveillance Summaries. Youth tobacco surveillance--United States, 2000. MMWR. 2001;50:1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control Surveillance Summaries. Tobacco use among middle and high school students --- United States, 2000–2009. MMWR. 2010;59:1063–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby EA, Roll JM, Ledgerwood DM, Schuster CR. Contingency management interventions for treating the substance abuse of adolescents: a feasibility study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:371–376. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Rhoades L. Incremental effects of reward on creativity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:728–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder C, Leaver-Dunn D, Wang MQ, Nagy S, Green L. Organized group activity as a protective factor against adolescent substance use. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Reducing early smokers’ risk for future smoking and other problem behavior: insights from a five-year longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott BM, Faraday MM, Phillips JM, Grunberg NE. Adolescent and adult female rats differ in sensitivity to nicotine’s activity effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80:567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried AE. Academic intrinsic motivation in elementary and junior high school students. J Educ Psychol. 1985;77:631–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, Hartwell KJ, Lewis AL, Hiott DW, Deas D, Upadhyaya HP. Bupropion SR and contingency management for adolescent smoking cessation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;40:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw GM, Stanton A. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database System Rev. 2006:CD003289. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedman L, Bjerg A, Perzanowski M, Sundberg S, Ronmark E. Factors related to tobacco use among teenagers. Respir Med. 2007;101:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Solomon LJ, Bernstein IM, Lussier JP, Abel RL, Lynch ME, Badger GJ. A pilot study on voucher-based incentives to promote abstinence from cigarette smoking during pregnancy and postpartum. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:1015–1020. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331324910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH. Contingency Management in Substance Abuse Treatment. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler DA, Natanblut SL, Wilkenfeld JP, Lorraine CC, Mayl SL, Bernstein IB, Thompson L. Nicotine addiction: a pediatric disease. J Pediatr. 1997;130:518–524. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Duhig AM, McKee SA, McMahon TJ, Liss T, McFetridge A, Cavallo DA. Contingency management for smoking cessation in adolescent smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:306–310. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Duhig AM, Cavallo DA. Adolescents. In: Higgins ST, Silverman K, Heil SH, editors. Contingency Management In The Treatment Of Substance Use Disorders: A Science-Based Treatment Innovation. Guilford Press; New York: 2008. pp. 222–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW, Shaffer D, Regier DA, Narrow WE, Bourdon K, Dulcan MK, Canino G, Rubio-Stipec M, Lahey BB, Friman P. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiat. 2001;40:443–449. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P, Colwell B, Backinger CL, Husten C, Maule CO. Better practices for youth tobacco cessation: evidence of review panel. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(Suppl 2):S144–158. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein R, Colby SM, Patten C, Prokhorov A, Brown R, Myers M, Adelman W, Hudmon K, McDonald P. Methodological issues in measuring treatment outcome in adolescent smoking cessation studies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:395–403. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000018470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Simcic F., Jr Recent advances in the dissemination of contingency management techniques: clinical and research perspectives. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:81–86. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piko BF, Fitzpatrick KM. Substance use, religiosity, and other protective factors among Hungarian adolescents. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich PR, De Groot EV. Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. J Educ Psychol. 1990;82:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Pallonen UE, Fava JL, Ding L, Niaura R. Measuring nicotine dependence among high-risk adolescent smokers. Addict Behav. 1996;21:117–27. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey CJ, McKeown RE, Sargent RG, Valois RF. Patterns of tobacco and alcohol use among sedentary exercising, nonathletic, and athletic youth. J Sch Health. 1996;66:27–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb06254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JM, Plate PC, Ernst M. Neural systems underlying motivated behavior in adolescence: implications for preventive medicine. Prev Med. 2012;55:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM. Assessing the feasibility of using contingency management to modify cigarette smoking by adolescents. J Appl Behav Anal. 2005;38:463–467. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.114-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Desai RA, Cavallo DA, Smith AE, McFetridge A, Liss TB, Potenza MN, Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender differences in adolescent marijuana use and associated psychosocial characteristics. J Addict Med. 2011;5:65–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d8dc62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Duhig AM, Liss T, McFetridge A, Wu R, Cavallo DA, Dahl T, Jatlow P, Krishnan-Sarin S. Contingency management for smoking cessation: enhancing feasibility through use of immunoassay test strips measuring cotinine. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1495–1501. doi: 10.1080/14622200802323209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Patrick ME. The use of financial incentives in promoting smoking cessation. Prev Med. 2012;55:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Cavallo DA, McFetridge A, Liss T, Krishnan-Sarin S. Preliminary examination of tobacco withdrawal in adolescent smokers during smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1253–1259. doi: 10.1080/14622200802219357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Toneatto T, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Johnson L. Alcohol abusers’ perceptions of the accuracy of their self-reports of drinking: implications for treatment. Addict Behav. 1992;17:507–511. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90011-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Jones RM, Casey BJ. A time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain Cogn. 2010;72:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Budney AJ. Contingency management approaches for adolescent substance use disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2010;19:547–562. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S. Effects of sixty six adolescent tobacco use cessation trials and seventeen prospective studies of self-initiated quitting. Tob Induc Dis. 2002;1:35–81. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-1-1-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW. Using incentives to reduce substance use and other health risk behaviors among people with serious mental illness. Prev Med. 2012;55:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, Galvin R, Zhu J, Wan F, DeGuzman J, Corbett E, Weiner J, Audrain-McGovern J. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman W, Glasgow R, Biglan A, Lichtenstein E. Development and preliminary evaluation of a cessation program for adolescent smokers. Psychol Addict Behav. 1987;1:84–91. [Google Scholar]