Developmental dyscalculia (DD) and its treatment are receiving increasing research attention. A PsychInfo search for peer-reviewed articles with dyscalculia as a title word reveals 31 papers published from 1991–2001, versus 74 papers published from 2002–2012. Still, these small counts reflect the paucity of research on DD compared to dyslexia, despite the prevalence of mathematical difficulties. In the UK, 22% of adults have mathematical difficulties sufficient to impose severe practical and occupational restrictions (Bynner and Parsons, 1997; National Center for Education Statistics, 2011). It is unlikely that all of these individuals with mathematical difficulties have DD, but criteria for defining and diagnosing dyscalculia remain ambiguous (Mazzocco and Myers, 2003). What is treated as DD in one study may be conceptualized as another form of mathematical impairment in another study. Furthermore, DD is frequently—but, we believe, mistakenly- considered a largely homogeneous disorder. Here we advocate a differential and developmental perspective on DD focused on identifying behavioral, cognitive, and neural sources of individual differences that contribute to our understanding of what DD is and what it is not.

Heterogeneity is a feature of DD

DD is not synonymous with all forms of arithmetic and mathematical difficulties1. Here we emphasize that DD is characterized by severe arithmetic difficulties and accounts for only a subset of individuals with arithmetic difficulties [see Figure 2 in Kaufmann and von Aster (2012)]. In studies including children with various manifestations of arithmetic difficulties, true deficits of DD are likely to be masked because DD represents only a minority of children in these samples (Murphy et al., 2007; LeFevre et al., 2010). Any theory of DD must account for differences between DD and individual differences in arithmetic in the general population. Kaufmann and Nuerk (2005) claimed that, “… average arithmetic development does not pursue a straight, fully predictable course of acquisition, but rather can be characterized by quite impressive individual differences” (Siegler, 1995; Dowker, 2005). Arithmetic ability consists of many components [e.g., memorizing facts, executing procedures, understanding, and using arithmetical principles (Desoete et al., 2004; Dowker, 2005, 2008)], each subject to individual differences that continue into adulthood (Dowker, 2005; Kaufmann et al., 2011a) and may contribute to the reported prevalence of low numeracy (Geary et al., 2013). These individual differences must be considered when defining DD, because assumptions about a single core deficit (e.g., Butterworth, 2005) do not support the range of clinical manifestations of DD.

Moreover, heterogeneity of DD and other mathematics difficulties is also fostered by environmental factors, ranging from cultural factors (e.g., nature and extent of schooling, characteristics of the counting system) to the effects of pre-/postnatal illness or socio-emotional adversity (e.g., math anxiety). Hence, arithmetic difficulties may be associated with other learning disorders (i.e., dyslexia) or with various neuropsychiatric and pediatric disorders (e.g., attention-deficit hyperactivity-disorder/ADHD, epilepsy; Shalev and Gross-Tsur, 1993; Marzocchi et al., 2002; Kaufmann and Nuerk, 2008). Disentangling these types of arithmetic difficulties may be important given recent evidence that treating an underlying medical condition (i.e., attention disorder) may alleviate the arithmetic difficulties (Rubinsten et al., 2008).

Below, we emphasize the need for a developmental view on DD and suggest definitional criteria acknowledging its developmental nature, heterogeneous manifestations and distinctness from other forms of arithmetic/mathematical difficulties.

Towards a developmental perspective on DD

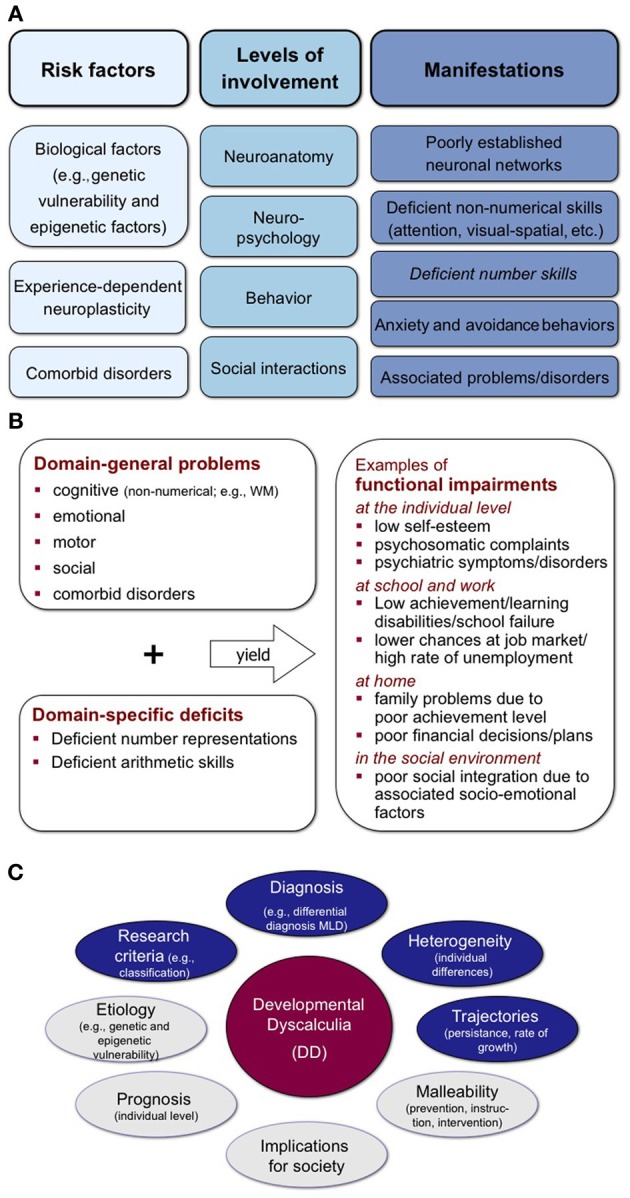

A developmental perspective enables us to trace pathways of parallel and/or sequential mechanisms at varying processing levels (neuroanatomical, neuropsychological, behavioral, interactional; Figure 1A). Important questions facing researchers include whether DD represents the extreme end of a continuum (or several continua) of mathematical ability or whether the arithmetic difficulties associated with DD are qualitatively different from more common mathematics difficulties. There is evidence to support each of these positions.

Figure 1.

(A) A development and integrative perspective on DD. (B) Schematic representation of potential clinical manifestations of DD. (C) Schematic representation of key areas for future research endeavors targeted at elaborating true development conceptualizations of DD. Please note that topics written in gray ellipses are not the focus of the present paper, but are nevertheless important issues that await further systematic investigations.

Arithmetic difficulties can reflect individual differences in both numerical and non-numerical functions. The numerical functions comprise many aspects of “number sense” such as spontaneous focusing on number (Hannula et al., 2010), comparing numerical quantities represented non-symbolically (e.g., as dot arrays; Piazza et al., 2010; Halberda et al., 2012), processing numbers symbolically (e.g., in Arabic notation; Stock et al., 2010), or linking non-symbolic representations to symbols such as number words and Arabic numerals (Rubinsten et al., 2002; Rubinsten and Henik, 2005; Bugden and Ansari, 2011). These individual differences in “number sense” may reflect variation in neural pathways involved in even quite rudimentary aspects of numerical cognition (e.g., single digit arithmetic: Price et al., 2013). Studies of functional activation during magnitude comparison reflect developmental variations over time (for respective meta-analyses, see Houdé et al., 2010; Kaufmann et al., 2011b) and suggest variation in development per se rather than in comparable but delayed trajectories (Vogel and Ansari, 2012; Price et al., 2013).

Recently, Moeller et al. (2012) distinguished the following approaches: (i) DD is related to a numerical core deficit, (ii) DD subtypes exist due to domain-general processes, and (iii) DD subtypes exist due to domain-specific numerical deficits beyond the aforementioned core numerical deficit. The core deficit hypothesis assumes that DD is a coherent syndrome mainly linked to neurofunctional peculiarities of the intraparietal sulcus (Butterworth, 2005). However, the heterogeneous clinical picture of DD (Figure 1B) is at odds with a single core deficit assumption (Mazzocco, 2007; Rubinsten and Henik, 2009). The second approach suggests that different subtypes can be distinguished on the basis of associated domain-general deficits. For instance, deficits in verbal (working) memory, semantic memory or visual-spatial skills (Rourke and Conway, 1997; von Aster, 2000; Geary, 2004) and even in belief-laden logical reasoning (Morsanyi et al., 2013) reportedly influence arithmetic difficulties (although some results contradict any view of simple relationships between verbal/spatial discrepancies and arithmetical components; Dowker, 1998). Respective developmental calculation models acknowledging non-numerical influences have been proposed previously (von Aster and Shalev, 2007; Kaufmann et al., 2011b). Such domain-general cognitive deficits may account for individual differences in the clinical picture despite comparable core numerical deficits. Finally, domain-specific numerical deficits (Wilson and Dehaene, 2007) may reflect multiple and distinct genuinely numerical deficits specifically affecting magnitude representation, verbal number representations, arithmetic fact knowledge, visual-spatial number forms, ordinality, base-10-system, or finger representations of numbers (Temple, 1991; Mazzocco et al., 2011; Moeller et al., 2012).

Current challenges related to DD classification, diagnosis, and research criteria

These aforementioned theoretical assumptions have important consequences for DD diagnosis and research. If, for instance, some children have severe problems in arithmetic fact retrieval but perform adequately on other numerical and arithmetic assessment tasks, they might not be classified as dyscalculic or even arithmetically impaired when assessments rely on a composite score comprising different numerical and arithmetic tasks. Deficits in one or few subsets that do not qualify for a DD diagnosis may still constitute severe problems for those children. In research designs, such delineated deficits might be undetected by group studies because averaging across participants and processes may mask deficits displayed by minorities (Siegler, 1987). The opposite risk also exists: children may be labeled, by themselves or others, as weak at arithmetic based on a specified difficulty despite average or high ability in other areas of arithmetic. This may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies or contribute to significant mathematics anxiety. Indeed, among young children, most studies suggest relatively little relationship between anxiety and performance, while in older children and adults, the relationship is strong and bidirectional; anxiety affects performance, and poor performance leads to anxiety (e.g., Ashcraft and Kirk, 2001; Mazzone et al., 2007; Pixner and Kaufmann, 2013).

Another major challenge of research on DD is the extensive range seen in diagnostic criteria and assessment tools used, which may influence research results (Murphy et al., 2007; Moser Opitz and Ramseier, 2012; Devine et al., 2013). As discussed by Moeller et al. (2012), there is little agreement about which children belong in the target group (DD, mathematical learning disability, etc.). Methodological approaches vary in terms of the cut-off points for classification criteria (ranging from <10 to <35 percentiles), whether reported percentiles reflect standardized or sample-based rankings, or deviations based on the population means and SDs. When different approaches are used across studies, very different children are included in study samples, and thus different background characteristics may be controlled for. Even children with general cognitive deficits may be included if a significant discrepancy between average intellectual abilities and sub-average math skills is not required as definitional criterion (as requested by the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Ehlert et al., 2012).

A final major challenge concerns the actual differential diagnostic classification tasks used in studies examining DD. While some studies employ discrete numerical tasks (e.g., dot enumeration), other studies use standardized math tests that may involve logical reasoning or text comprehension. Hence, apparently contradictory results as to whether DD involves deficits in basic or more complex numerical abilities may stem from the use of different classification tasks across studies. Discrepant findings may also reflect different samples of children who are nevertheless all presumed to have DD. The need is for research on DD to be both comprehensive and comparable across studies, which calls for a consortium-based proposal to adopt international standard diagnostic tools that are comparable across countries, curricula and therefore studies, in addition to study-specific assessments (as applicable).

How developmental conceptualizations of DD may guide educational and therapeutic approaches

Beyond its scientific value, developmental conceptualizations of DD are crucial in guiding effective educational and therapeutic strategies. Researchers must consider the utility and meaningfulness of their contributions to the public perception of DD (including perceptions of teachers and parents). For instance, neurodevelopmental disorders like DD are at least partially attributable to inherited genetic differences (Shalev et al., 2001; Kovas et al., 2007). Hence, when conceptualized as a homogeneous and inborn disorder, DD may be misinterpreted as immune to the effects of behavioral interventions. A developmental approach considers multiple factors interacting to contribute to manifestations of DD. Such an approach is adopted in the forthcoming DSM-V, which replaces the categorical DSM-IV definition of distinct learning disorders (reading/written expression/mathematics) with an overarching multi-dimensional diagnosis of “Specific Learning Disorders” that acknowledges distinct manifestations of learning difficulties in various academic domains. However, in the theoretical debate about domain-specific versus domain-general underpinnings of DD, it is important to recall that domain-general deficits early on in development may result in seemingly domain-specific deficits in later development, because the earlier deficits may be more relevant to the computational demands of one domain (e.g., number) while still affecting other domains albeit to a more subtle degree. The reverse may also be true: numerical deficits may manifest as domain general deficits in, for instance, attention or working memory when diagnostic tools draw on numerical stimuli.

While advocating a developmental and differential perspective on DD, we must also caution against over-relying on adult neuropsychological patients with acquired mathematics disorders as models of DD (Kaufmann and Nuerk, 2005; Ansari, 2010; Karmiloff-Smith et al., 2012). As Karmiloff-Smith (1998) explains, important differences exist between deficits that arise during development versus those resulting from damage to an existing system. Therefore, we argue that (i) DD is a heterogeneous disorder resulting from individual differences in development or function at neuroanatomical, neuropsychological, behavioral, and interactional levels (Figure 1A), and that (ii) an understanding of these differences can facilitate DD diagnosis and intervention. The acknowledgement of individual differences characterizing DD calls for adequate methodological and differential diagnostic approaches, and adequate attention to the developmental component of DD (reflecting systematic inter- and intra-individual variations between age and skill levels) (Figure 1C). Solid developmental conceptualizations of DD may foster the acceptance of DD as a disorder and raise public awareness for the need to provide targeted educational, therapeutic, and structural support tailored to affected individuals (Figure 1B), as well as differentiating DD from other sources of difficulty in children underperforming in mathematics.

As a synopsis of our arguments, we propose the following preliminary definition of DD:

Primary DD is a heterogeneous disorder resulting from individual deficits in numerical or arithmetic functioning at behavioral, cognitive/neuropsychological and neuronal levels. The term secondary DD should be used if numerical/arithmetic dysfunctions are entirely caused by non-numerical impairments (e.g., attention disorders)2.

Further, we postulate the following recommendations for primary DD (and its diagnosis):

There is convincing evidence that basic numerical skills are impaired in DD. Therefore, purely educational (curricular) tests are not adequate to tap the characteristic numerical deficits associated with DD.

DD is a heterogeneous disorder (like other neurodevelopmental disorders). Multi-dimensional assessments tracking different numerical representations and arithmetic processes should be used to evaluate response accuracy, speed, and strategies.

Specific deficits in numerical subdomains are possible, even when overall dyscalculia test scores are unremarkable.

Arithmetic performance of children diagnosed with DD can be unstable over development and time; thus children who are reasonably close to formal DD criteria (usually scoring <10th percentile) should be retested within the following school semester/year. Conservatively, retesting is recommended if performance is <25th percentile.

Currently, there is no evidence that focusing on discrepancies between numerical and general cognitive skills improves diagnostic accuracy or interventional outcomes.

DD can be comorbid with other neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, and neuropediatric disorders that may affect the regulation of motor/executive/affective/socio-behavioral functioning and have to be considered for differential diagnosis.

Educational and socio-emotional characteristics should be considered in diagnosing and ruling out DD.

Acknowledgments

The work of Ann Dowker was supported by the Esmee Fairbairn Charitable Trust. The work of Avishai Henik and Orly Rubinsten was conducted as part of the research in the Center for the Study of the Neurocognitive Basis of Numerical Cognition, supported by the Israel Science Foundation (Grants 1799/12 and 1664/08) in the framework of their Centers of Excellence. Denes Szucs was supported by Medical Research Council (UK) grant G90951. Dyscalculia research of Hans-Christoph Nuerk was supported by the ScienceCampus Tübingen (TP8.4).

Footnotes

1The terms “arithmetic” and “mathematical” are not synonymous as the former refers to computational skills (i.e., processing of basic arithmetical operations such as addition/subtraction/multiplication) and the latter encompasses other aspects of numerical thinking such as algebra, geometry, etc.

2Likewise, Geary (2007) distinguished primary and secondary biological routes to math learning disabilities.

References

- Ansari D. (2010). Neurocognitive approaches to developmental disorders of numerical and mathematical cognition: the perils of neglecting development. Learn. Indiv. Diff. 20, 123–129 10.1016/j.lindif.2009.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcraft M. H., Kirk E. P. (2001). The relationship among working memory, math anxiety and performance. J. Exp. Psychol. 130, 224–237 10.1037/0096-3445.130.2.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugden S., Ansari D. (2011). Individual differences in children's mathematical competence are related to the intentional but not automatic processing of Arabic numerals. Cognition 118, 32–44 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterworth B. (2005). The development of arithmetical abilities. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46, 3–18 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynner J., Parsons S. (1997). Does Numeracy Matter. Evidence from the National Child Development Study on the Impact of Poor Numeracy on Adult Life. London: Basic Skills Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Desoete A., Roeyers H., De Clercq A. (2004). Children with mathematics learning disabilities in Belgium. J. Learn. Disabil. 37, 50–61 10.1177/00222194040370010601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine A., Soltész F., Nobes A., Goswami U., Szucs D. (2013). Gender differences in developmental dyscalculia depend on diagnostic criteria. Learn. Instruc. 27, 31–39 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowker A. (2005). Individual Differences in Arithmetical Abilities: Implications for Psychology, Neuroscience and Education. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 10.4324/9780203324899 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dowker A. (2008). Individual differences in numerical abilities in preschoolers. Dev. Sci. 11, 650–654 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00713.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowker A. D. (1998). Individual differences in normal arithmetical development, in The Development of Mathematical Skills, ed Donlan C. (East Sussex, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; ), 275–302 [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert A., Schroeders U., Fritz-Stratmann A. (2012). Kritik am Diskrepanzkriterium in der Diagnostik von Legasthenie und Dyskalkulie. [Criticism of the discrepancy criterion in the diagnosis of dyslexia and dyscalculia]. Lern. Lernstör. 1, 169–184 (Full article in German, extended abstract in English). 10.1024/2235-0977/a000018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geary D. C. (2004). Mathematics and learning disabilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 37, 4–15 10.1177/00222194040370010201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geary D. C. (2007). Educating the evolved mind: conceptual foundations for an evolutionary educational psychology, in Educating the Evolved Mind, Vol. 2, eds Carlson J. S., Levin J. R. (Psychological perspectives on contemporary educational issues). Greenwich, CT: Information Age; ), 1–99 [Google Scholar]

- Geary D. C., Hoard M. K., Nugent L., Bailey D. H. (2013). Adolescents' functional numeracy is predicted by their school entry number system knowledge. PLoS ONE 8:e54651 10.1371/journal.pone.0054651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberda J., Ly R., Wilmer J. B., Naiman D. Q., Germine L. (2012). Number sense across the lifespan as revealed by a massive Internet-based sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 11116–11120 10.1073/pnas.1200196109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannula M. M., Lepola J., Lehtinen E. (2010). Spontaneous focusing on numerosity as a domain-specific predictor of arithmetical skills. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 107, 394–406 10.1016/j.jecp.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdé O., Rossi S., Lubin A., Joliot M. (2010). Mapping numerical processing, reading, and executive functions in the developing brain: an fMRI meta-analysis of 52 studies including 842 children. Dev. Sci. 13, 876–885 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00938.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A. (1998). Development itself is the key to understanding developmental disorders. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2, 389–398 10.1016/S1364-6613(98)01230-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmiloff-Smith A., D'Souza D., Dekker T. M., Van Herwegen J., Xu F., Rodic M., et al. (2012). Genetic and environmental vulnerabilities in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 17261–17265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann L., Nuerk H.-C. (2005). Numerical development: current issues and future perspectives. Psychol. Sci. 47, 142–170 21970719 [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann L., Nuerk H.-C. (2008). Basic number processing deficits in ADHD: a broad examination of elementary and complex number processing skills in 9 to 12 year-old children with ADHD-C. Dev. Sci. 11, 692–699 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00718.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann L., Pixner S., Göbel S. (2011a). Finger usage and arithmetic in adults with math difficulty: evidence from a case report. Front. Cogn. 2:254 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann L., Wood G., Rubinsten O., Henik A. (2011b). Meta-analysis of developmental fMRI studies investigating typical and atypical trajectories of number processing and calculation. Dev. Neuropsychol. 36, 763–787 10.1080/87565641.2010.549884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann L., von Aster M. (2012). The diagnosis and management of dyscalculia. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 109, 767–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovas Y., Haworth C. M. A., Petrill S. A., Dale P. S., Plomin R. (2007). Overlap and specificity of genetic and environmental influences on mathematics and reading disabilitiesin 10-year-old twins. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 914–922 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01748..x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeFevre J. A., Fast L., Skwarchuk S. L., Smith-Chant B. L., Bisanz J., Kamawar D., et al. (2010). Pathways to mathematics: longitudinal predictors of performance. Child Dev. 81, 1753–1767 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01508.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzocchi G. M., Lucangeli D., De Meo T., Fini F., Cornoldi C. (2002). The disturbing effect of irrelevant information on arithmetic problem solving in inattentive children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 21, 73–92 10.1207/S15326942DN2101_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco M. M. M. (2007). Defining and differentiating mathematical learning disabilities and difficulties, in Why is Math So Hard for Some Children: The Nature and Origins of Mathematics Learning Difficulties and Disabilities, eds Berch D. B., Mazzocco M. M. M. (Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes; ), 29–47 [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco M. M. M., Feigenson L., Halberda J. (2011). Impaired acuity of the approximate number system underlies mathematical learning disability (dyscalculia). Child Dev. 82, 1224–1237 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocco M. M., Myers G. F. (2003). Complexities in identifying and defining mathematics learning disability in the primary school-age years. Ann. Dyslexia 53, 218–253 10.1007/s11881-003-0011-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone L., Ducci F., Scoto M. C., Passaniti E., Genitori D'Arrigo V., Vitiello B. (2007). The role of anxiety symptoms in school performance in a community based sample of children and adolescents. BMC Public Health 7:347 10.1186/1471-2458-7-347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller K., Fischer U., Link T., Wasner M., Huber S., Cress U., et al. (2012). Learning and development of embodied numerosity. Cogn. Process. 13Suppl. 1, 271–274 10.1007/s10339-012-0457-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsanyi K., Devine A., Nobes A., Szucs D. (2013). The link between logics, mathematics and imagination: evidence from children with developmental dyscalculia and mathematically gifted children. Dev. Sci. 16, 542–553 10.1111/desc.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser Opitz E., Ramseier E. (2012). Rechenschwach oder nicht rechenschwach. Eine kritische Auseinandersetzung mit Diagnosekonzepten, Klassifikationssystemen und Diagnoseinstrumenten unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von älteren Schülerinnen und Schülern [Mathematical Learning Disabilities: a critical examination of diagnostic conceptx, classification systems and diagnostic instruments, with particular consideration of older students]. Lern. Lernstör. 1, 99–117 (Full article in German, extended abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M. M., Mazzocco M. M., Hanich L. B., Early M. C. (2007). Cognitive characteristics of children with mathematics learning disability (MLD) vary as a function of the cutoff criterion used to define MLD. J. Learn. Disabil. 40, 458–478 10.1177/00222194070400050901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). The Condition of Education 2011. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2011/2011033.pdf

- Piazza M., Facoetti A., Trussardi A. N., Berteletti I., Conte S., Lucangeli D., et al. (2010). Developmental trajectory of number acuity reveals a severe impairment in developmental dyscalculia. Cognition 116, 33–41 10.1016/j.cognition.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pixner S., Kaufmann L. (2013). Prüfungsangst, Schulleistung und Lebensqualität bei Schülern [Exam anxiety, school achievement and quality of life in third and sixth grade students]. Lern. Lernstör. 2, 111–124 (Full article in German, extended abstract in English). 10.1024/2235-0977/a000034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Price G. R., Mazzocco M. M., Ansari D. (2013). Why mental arithmetic counts: brain activation during single digit arithmetic predicts high school math scores. J. Neurosci. 33, 156–116 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2936-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rourke B. P., Conway J. A. (1997). Disabilities of arithmetic and mathematical reasoning perspectives from neurology and neuropsychology. J. Learn. Disabil. 30, 34–46 10.1177/002221949703000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsten O., Bedard A.-C., Tannock R. (2008). Methylphenidate has differential effects on numerical abilities in ADHD children with and without co-morbid mathematical disabilities. Open Psychol. J. 1, 11–17 10.2174/1874350100801010011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsten O., Henik A. (2005). Automatic activation of internal magnitudes: a study of developmental dyscalculia. Neuropsychology 19, 641–648 10.1037/0894-4105.19.5.641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsten O., Henik A. (2009). Developmental dyscalculia: heterogeneity might not mean different mechanisms. Trends Cogn. Sci. 13, 92–99 10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsten O., Henik A., Berger A., Shahar-Shalev S. (2002). The development of internal representations of magnitude and their association with Arabic numerals. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 81, 74–92 10.1006/jecp.2001.2645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev R. S., Gross-Tsur V. (1993). Developmental dyscalculia and medical assessment. J. Learn. Disabil. 36, 134–137 10.1177/002221949302600206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev R. S., Manor O., Kerem B., Ayali M., Badihi N., Friedlander Y., et al. (2001). Familial-genetic facets of developmental dyscalculia. J. Learn. Disabil. 34, 59–65 10.1177/002221940103400105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler R. S. (1987). The perils of averaging data over strategies: an example from children's addition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 116, 250–264 10.1037/0096-3445.116.3.250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegler R. S. (1995). How does change occur: a microgenetic study of number conservation. Cogn. Psychol. 28, 225–273 10.1006/cogp.1995.1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock P., Desoete A., Roeyers H. (2010). Detecting children with arithmetic disabilities from kindergarten: evidence from a 3-year longitudinal study on the role of preparatory arithmetic abilities. J. Learn. Disabil. 43, 250–268 10.1177/0022219409345011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple C. M. (1991). Procedural dyscalculia and number fact dyscalculia: double dissociation in developmental dyscalculia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 8, 155–176 10.1080/02643299108253370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. E., Ansari D. (2012). Neurokognitive Grundlagen der typischen und atypischen Zahlenverarbeitung. [Neurocognitive foundations of typical and atypical number development]. Lern. Lernstör. 1, 135–149 (Full article in German, extended abstract in English). 10.1024/2235-0977/a000015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Aster M. G. (2000). Developmental cognitive neuropsychology of number processing and calculation: varieties of developmental dyscalculia. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 9, 41–58 10.1007/s007870070008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Aster M. G., Shalev R. S. (2007). Number development and developmental dyscalculia. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 49, 868–873 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00868.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. J., Dehaene S. (2007). Number sense and developmental dyscalculia, in Human Behavior and the Developing Brain, eds Coch D., Fischer K., Dawson G. (New York, NY: Guildford Press; ), 212–238 [Google Scholar]