Abstract

Despite having the highest Plasmodium vivax burden in the world, molecular epidemiological data from Papua New Guinea (PNG) for this parasite remain limited. To investigate the molecular epidemiology of P. vivax in PNG, 574 isolates collected from four catchment sites in East Sepik (N = 1) and Madang (N = 3) Provinces were genotyped using the markers MS16 and msp1F3. Genetic diversity and prevalence of P. vivax was determined for all sites. Despite a P. vivax infection prevalence in the East Sepik (15%) catchments less than one-half the prevalence of the Madang catchments (27–35%), genetic diversity was similarly high in all populations (He = 0.77–0.98). High genetic diversity, despite a marked difference in infection prevalence, suggests a large reservoir of diversity in P. vivax populations of PNG. Significant reductions in transmission intensity may, therefore, be required to reduce the diversity of parasite populations in highly endemic countries such as PNG.

Introduction

With malaria elimination now firmly back on the global agenda, Plasmodium vivax is emerging as a substantial obstacle to progress.1 Much remains to be understood regarding the biology, pathogenesis, and epidemiology of this parasite, which has long been neglected as a research priority, largely due to misclassification of P. vivax infections as benign.2,3 It is now thought that the global public health risk posed by P. vivax may be far greater than first anticipated as a result of its complex lifecycle, its broader global distribution than P. falciparum, and the potentially severe or fatal clinical disease associated with infection.4

Mapping the local and global population structure of P. vivax is essential both before and after the rollout of intervention measures and when establishing goals for elimination,5,6 as parasite populations can differ widely between locations due to vector prevalence, host genetics, and a variety of environmental factors.7–10 Population genetic surveys to determine the diversity of P. vivax parasites within a given human population can reveal insights into the potential resilience of the parasite population to interventions.

Additionally, as individuals infected with P. vivax are often infected with multiple clones, it is important to identify genetically distinct clones both between infections and within the same infection. Either one or two highly polymorphic markers or a larger number of less polymorphic genome-wide markers are generally used to genotype samples and identify distinct parasite clones. The diversity of a given marker and the number of markers required to accurately genotype P. vivax infections will, however, differ between geographical locations due to variations in malaria epidemiology.11–13 As such, the suitability of genotyping markers for a specific geographic location or region should be assessed before use. A panel of nine markers for genotyping P. vivax isolates was previously evaluated using samples collected in Papua New Guinea (PNG).13 Three markers—MS16, pv3.27, and msp1F3—were identified as the most genetically diverse in the PNG parasite population investigated and therefore, best suited to identify individual clones. In a subsequent study by Koepfli and others,14 it was reported that using the unlinked MS16 and msp1F3 markers combined was sufficient to identify genetically distinct clones from the highly endemic Maprik region in East Sepik Province of PNG, and also that the genetic diversity of P. vivax within this region is very high.14

The burden of P. vivax infection in PNG is the highest of any country in the world.15 More than 90% of the PNG population is at high risk of malaria,16 with the highest incidence of infection among children < 5 years.17 Despite 9 of 10 principle malaria-endemic countries in the Western Pacific region reporting downward trends in malaria in 2011, the number of malaria cases reported in PNG remained relatively stable.16 Furthermore, 36% of 262,000 malaria cases reported in the Western Pacific region in 2010 occurred in PNG, the highest burden of any single nation within the region.16 In PNG, transmission of the four major human malaria parasites (P. vivax, P. falciparum, P. malariae, and P. ovale) occurs year round.15,17,18 The intensity of malaria transmission ranges from epidemic outbreaks and low transmission in the highlands to holoendemic in the lowlands and coastal regions, which is similar in intensity to sub-Saharan Africa.15 Because of the enormous burden of P. vivax in PNG coupled with the inherent difficulties associated with P. vivax elimination, including the absence of a continuous in vitro culture system to investigate P. vivax biology and the formation of long-lived liver hypnozoites confounding attempts to interrupt transmission, progress to elimination is likely to be slow. The results obtained from studies performed to investigate P. vivax population genetic diversity and structure in distinct regions within PNG, where transmission intensity varies, will be useful in both a local (enabling the impact of subsequent interventions to be measured) and a global context (contributing to knowledge of P. vivax population complexity).

The aim of this study was to investigate the genetic diversity of P. vivax in the East Sepik and Madang Provinces of PNG and to compare this information with infection prevalence in the different areas. Archived P. vivax isolates collected in cross-sectional surveys of four distinct catchments were genotyped using the highly polymorphic markers MS16 and msp1F3. The genetic diversity found in each population was then measured based on these genotypes, and the results compared with the infection prevalence. The results have important implications for the control of P. vivax malaria in highly endemic regions.

Materials and Methods

Study sites and P. vivax isolates.

Madang and East Sepik Provinces are subject to intense perennial malaria transmission and have long been the focus of malaria research and control efforts.19 The catchment areas in these two provinces are separated by approximately 350 km of mountainous and swampy terrain, and overland travel between the two locations is not possible.20 A map of PNG showing the location of the study sites can be found in the work by Schultz and others.8 To capture the diversity of the circulating parasite population, finger prick or venous blood was collected from asymptomatic volunteers of all ages in cross-sectional malaria surveys conducted as part of an Intermittent Preventative Treatment in Infants Trial.8 In East Sepik Province, 1,077 samples were collected in the relatively dry months between August and September of 2005 from individuals residing in the Wosera catchment area that encompasses seven villages spaced 2–10 km apart (Gwinyingi, Patigo, Kausaugu, Nindigo, Kitikum, Wisogum, and Tatemba). In Madang Province, 1,282 samples were collected in the rainy season of March of 2006 from individuals residing in three distinct catchment areas each encompassing one to five villages within 5–20 km of each other. These catchments include Mugil, comprising the villages of Dimer, Karkum, Matukar, and Bunu; Malala, including Amiten, Susure, Malala, Suraten, and Wakorma; and the area surrounding Utu health center. For the purposes of this study, samples collected from individual villages within specific catchment areas of East Sepik and Madang Provinces were combined to form geographically distinct populations for analysis, including two provincial populations (East Sepik and Madang) and four catchment populations (Wosera, Mugil, Malala, and Utu). Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and parents or legal guardians of minors. Ethical approval to conduct this study was granted by the PNG Institute of Medical Research Institutional Review Board (No. 11-05), the Medical Research Advisory Committee of PNG (No. 11-06), the Alfred Hospital Research and Ethics Unit (No. 420-10), and the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 11-12).

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole-blood samples using the 96-well QiaAmp DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Chadstone, Victoria, Australia). Light microscopy (LM) and ligase detection reaction–fluorescent microsphere assay (LDR-FMA) were performed to identify samples infected with P. vivax as described.21 The proportion of samples that was LM- or LDR-FMA–positive for P. vivax infection was used to determine the infection prevalence for both provinces and each catchment. To increase the available template volume for analysis, whole-genome amplification (WGA) was performed using the Illustra GenomiPhi V2 DNA Amplification Kit as per the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare, Rydalmere, New South Wales, Australia).

Genotyping.

MS16 and msp1F3 were selected to genotype P. vivax isolates in the present study, as it has been shown previously that diversity of the two markers is sufficiently high to enable high-resolution differentiation between genetically distinct strains.13,14 The MS16 marker is highly diverse and lacking in dominant alleles. Less diverse than MS16, the coding sequence of the msp1F3 marker is more complex than a microsatellite; therefore, artifacts introduced by slippage of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) polymerase are less likely to occur.14

Genotyping was performed as previously described,14 with the following alterations: a multiplex first-round PCR was performed using the HotMaster Taq DNA Polymerase Kit (5 Prime, Murarrie, Queensland, Australia) and the published MS16 and msp1F3 primer sequences of Koepfli and others.13 The primary PCR mastermix, in a final volume of 20 μL, consisted of 1 μL WGA template DNA, 2 μL 10× HotMaster Taq buffer with Mg2+, 0.25 μM each primer (Geneworks, Hindmarsh, South Australia, Australia), 0.2 mM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) (Roche, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia), and 1 U HotMaster Taq DNA polymerase (5 Prime). Thermocycling was performed under the following conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes; 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 56°C for 30 seconds, and primer extension at 65°C for 1 minute; final extension at 65°C for 5 minutes.

Nested PCR reactions were then performed on the primary product template using the HotMaster Taq DNA Polymerase Kit (5 Prime) and either the MS16 or msp1F3 nested PCR primer sequences of Koepfli and others.14 Nested PCR forward primers were labeled at the 5′ end with a fluorescent dye, and nested PCR reverse primers were modified by the addition of a proprietary 7-bp tail (Applied Biosystems, Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia) to the 5′ end as described.13 The nested PCR mastermix for both markers, in a final volume of 20 μL, consisted of 1 μL primary PCR template DNA, 2 μL 10× HotMaster Taq buffer with Mg2+, 0.25 μM forward and reverse primers (Applied Biosystems), 0.2 mM dNTPs (Roche), and 1 U HotMaster Taq DNA polymerase (5 Prime). Thermocycling was performed under the following conditions: denaturation at 94°C for 2 minutes; 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 58°C for 30 seconds, and primer extension at 65°C for 1 minute; final extension at 65°C for 5 minutes. Successfully amplified PCR products were then sent to a contract sequencing facility for fragment analysis using an ABI 3730XL automatic DNA analyzer and the Applied Biosystems 500LIZ size standard. The size standard 500LIZ was included in each sample lane.

Data analysis.

GeneScan chromatograms were analyzed using Peak Scanner, version 1.0 (Applied Biosystems). A cutoff of 1,000 relative fluorescence units (RFUs) was used to distinguish true peaks from background signal. As a result of run-to-run variation, the fluorescence intensity of some sample plates was reduced, and in this instance, the cutoff was lowered to 300 RFUs.13 All major peaks (i.e., those peaks within the size range with the highest RFUs) were scored. A stringent peak calling strategy was used: secondary and/or minor peaks were only scored if they reached at least 40% of the major peak for msp1F3 and 70% of the major peak for MS16. All scored peaks were visually inspected to confirm results.

Alleles were grouped manually according to size into bins of 3 bp, which is the size of the repeat unit for both MS16 and msp1F3.13,14 Isolates with single alleles for both markers were classified as single infections, whereas those isolates with multiple alleles for at least one marker were classified according to the highest number of alleles detected for either marker.

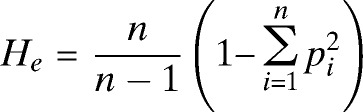

Diversity analysis was performed on the genotyping data using FSTAT software, version 2.9.322 and Arlequin, version 3.5.1.2.23 The number of alleles (A), the number of haplotypes (h), allele frequency and allelic richness (Rs is the expected number of alleles normalized on the basis of the smallest sample size)24 were calculated for each catchment area, province and for PNG total. Expected heterozygosity (He), the probability of two clones randomly sampled from a given population carrying a different allele, was calculated using the formula

|

where n is the number of alleles identified in a given population and p is the frequency of allele i.

Results

Prevalence of P. vivax on the north coast of PNG.

A total of 2,359 blood samples was collected from asymptomatic participants from the East Sepik and Madang regions of PNG. Infection with P. vivax was determined using both LM and LDR-FMA. Of 2,359 samples, 405 (17%) samples were identified as P. vivax-positive using LM, whereas 574 (24%) samples were identified using the more sensitive molecular approach of LDR-FMA (Table 1). Of 574 P. vivax LDR-FMA–positive samples, 409 (71.3%) samples were from Madang (Table 1), and 165 (28.7%) samples were from East Sepik. Based on these data, Madang Province had an overall infection prevalence of 32% (catchments = 27–35%), which was more than double the infection prevalence of East Sepik Province (15%) (Table 1). LM data were not available for 81 samples: 12 samples from Madang and 69 samples from East Sepik.

Table 1.

Prevalence of P. vivax infections in the Madang and East Sepik regions of PNG

| Province and catchment | n | P. vivax infection | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LM-positive (%) | LDR-FMA–positive (%) | ||

| East Sepik | 1,077 | 194 (18) | 165 (15) |

| Wosera | 1,077 | 194 (18) | 165 (15) |

| Madang | 1,282 | 211 (16) | 409 (32) |

| Malala | 379 | 70 (18) | 131 (35) |

| Mugil | 503 | 74 (14.7) | 167 (33) |

| Utu | 397 | 64 (16) | 109 (27) |

| PNG total* | 2,359 | 405 (17) | 574 (24) |

n, number of P. vivax-positive samples.

The total number of positive samples for PNG and Madang include three samples from which the Madang catchment of origin was unknown.

Samples were collected from participants of all ages at both study sites. Ages ranged between < 1 month and 72 years (median = 14 years) among participants from Madang and between < 1 month and 90 years (median = 14 years) among participants from East Sepik. Demographic data were available for 442 of 574 P. vivax LDR-FMA–positive samples; 49% (N = 220) of P. vivax-positive samples were collected from children ages < 10 years, with 19.8% of samples collected from children ages < 5 years. Information regarding the gender of participants from East Sepik was not available.

Genotyping of P. vivax isolates.

WGA, a method that has been used in similar molecular epidemiological studies,25–28 was performed prior to genotyping to increase the amount of P. vivax DNA for analysis. The multiple displacement amplification (MDA) method used in this study has been shown to result in a higher yield of non-artifact DNA template and reduced amplification bias compared with PCR-based WGA methods.29 To investigate whether artifacts were introduced as a result of WGA, sequences of msp1F3 and MS16 alleles amplified from undiluted genomic DNA and subjected to WGA were compared. Consistent with previous reports,26,27 results were concordant between the WGA and unamplified DNA (data not shown).

Of 574 P. vivax-positive samples, there was sufficient DNA to enable WGA and subsequent genotyping of 521 samples, of which 310 samples were PCR-positive for at least one of the genotyping markers. For 53 (17%) samples, MS16 only was successfully genotyped; for 63 (20.3%) samples, msp1F3 only was successfully genotyped, and for 194 samples, both MS16 and msp1F3 were successfully genotyped (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genetic diversity of P. vivax infections in the Madang and East Sepik regions of PNG

| Markers in the province and catchment | n | c | A | h | Rs | He |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS16 | ||||||

| East Sepik | 94 | 138 | 55 | n.a. | 55 | 0.98 |

| Wosera | 94 | 138 | 55 | n.a. | 47 | 0.98 |

| Madang | 152 | 237 | 69 | n.a. | 64 | 0.98 |

| Malala | 56 | 92 | 46 | n.a. | 43 | 0.97 |

| Mugil | 53 | 61 | 34 | n.a. | 34 | 0.96 |

| Utu | 43 | 84 | 43 | n.a. | 42 | 0.98 |

| PNG total | 246 | 375 | 82 | n.a. | 53 | 0.98 |

| msp1F3 | ||||||

| East Sepik | 87 | 103 | 17 | n.a. | 17 | 0.77 |

| Wosera | 87 | 103 | 17 | n.a. | 15 | 0.77 |

| Madang | 171 | 251 | 29 | n.a. | 24 | 0.86 |

| Malala | 54 | 92 | 16 | n.a. | 15 | 0.83 |

| Mugil | 72 | 94 | 15 | n.a. | 14 | 0.85 |

| Utu | 45 | 65 | 23 | n.a. | 23 | 0.91 |

| PNG total | 257 | 354 | 33 | n.a. | 20 | 0.85 |

| Both | ||||||

| East Sepik | 75 | 124 | 30 | 69 | n.a. | 0.88 |

| Wosera | 75 | 124 | 30 | 69 | n.a. | 0.88 |

| Madang | 119 | 218 | 38 | 122 | n.a. | 0.92 |

| Malala | 40 | 77 | 20 | 40 | n.a. | 0.89 |

| Mugil | 44 | 70 | 20 | 51 | n.a. | 0.91 |

| Utu | 35 | 71 | 20 | 37 | n.a. | 0.91 |

| PNG total | 194 | 342 | 46 | 177 | n.a. | 0.99 |

A = number of alleles; c = number of clones counted; h = number of haplotypes; He = expected heterozygosity; n = number of P. vivax isolates; n.a. = not applicable; Rs = allelic richness.

Genetic diversity of P. vivax populations on the north coast of PNG.

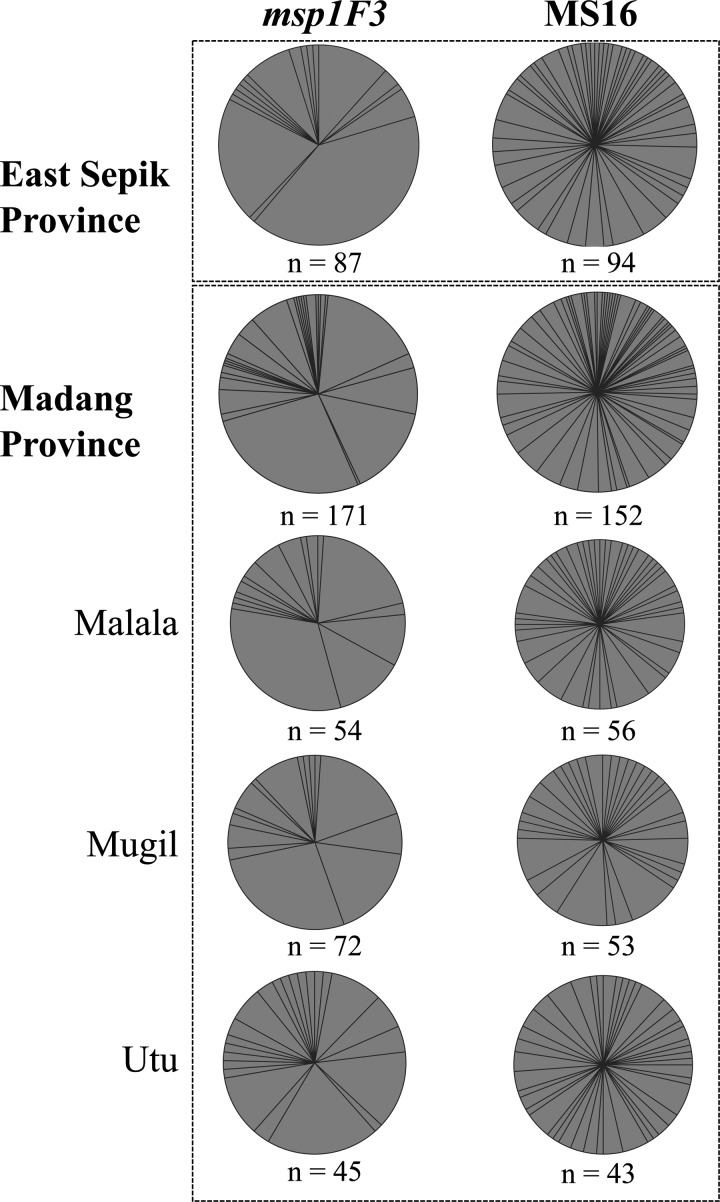

Among 310 P. vivax isolates, at least 487 individual clones were identified, and the alleles found amongst these clones were used to calculate diversity. The total number of alleles identified (A) was 82 for MS16 and 33 for msp1F3 (Figure 1, Table 2, and Supplemental Table 1). The most common msp1F3 allele was 265 bp in size and detected at a frequency of 30.8%. For MS16, the 377-bp allele was detected at the highest frequency of only 4.2% (Supplemental Table 1). Other parameters of diversity, including the expected heterozygosity (He) and allelic richness (Rs), were found to be high in all four catchments for each of the markers, although the range of values varied depending on the marker used, with msp1F3 showing lower and more variable values of Rs and He because of its lower overall diversity (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Genetic diversity of P. vivax populations on the north coast of PNG. Each wedge of the pie charts represents a single marker allele; the size of each wedge is proportional to the frequency of each allele within the specified population. The number of P. vivax isolates (n) from which markers were successfully amplified from each population is indicated.

Very high levels of diversity were also observed after analysis of combined MS16–msp1F3 haplotypes established from isolates considered to be single infections plus composite haplotypes from isolates with no more than two alleles at only one locus (N = 177) (Table 2). Despite a considerable difference in the P. vivax infection prevalence in Madang (32%) and East Sepik (15%) Provinces (Table 1), the genetic diversity was very high in both regions (He = 0.92 and He = 0.88, respectively). Similarly, in all four catchments investigated, the genetic diversity was very high (He = 0.88–0.91) (Table 2).

Although the use of two markers provides greater resolution to identify distinct clones, the genetic diversity measures of A, Rs, and He were not well-resolved among populations, which is also the case when extremely diverse markers, such as MS16, are used. Therefore, the analysis of msp1F3 provided the greatest resolution of differences among the populations. Based only on msp1F3, Rs and He values were highest for Utu, which is interesting given the lower prevalence compared with the other two Madang catchments. Rs and He values were lowest for Wosera, which is consistent with the lower prevalence in that catchment (Table 2). In summary, all populations showed high levels of genetic diversity, despite considerable variation in P. vivax infection prevalence.

Discussion

Molecular epidemiology is extremely useful to investigate beyond the traditional measures of parasite prevalence afforded by LM, because it enables the identification of distinct clones. Consequently, genetic diversity can be measured as an indication of parasite population complexity and potential resilience of populations to interventions. Several molecular markers, including both polymorphic microsatellite and minisatellite repeats and single nucleotide polymorphisms, have been characterized and widely used for molecular epidemiological studies of P. falciparum.30,31 Although consensus markers are yet to be determined for P. vivax, MS16 and msp1F3 were recently reported as being highly diverse after evaluation of a panel of potential P. vivax genotyping markers.13 MS16 has previously been used to assess the genetic diversity of P. vivax populations from Peru,32 Brazil,33 Vietnam,12 PNG,13,14 Sri Lanka, Ethiopia,25 Myanmar,25 and Korea.34 The diversity of MS16 among P. vivax isolates from a range of global endemic areas is reported to be medium to high (He [range] = 0.5–0.9),12,14,25,32–34 with the exception of a single report of very low levels of diversity among isolates from Ethiopia (He = 0.19). This low level of diversity in Ethiopia was despite high diversity of other microsatellite loci, suggesting that MS16 might be contained within a selective sweep in the Ethiopian parasite population.25 Fewer studies have been performed to investigate the genetic diversity of msp1F313,35; however, we and others have shown that use of the MS16 and msp1F3 markers combined can enable high-resolution identification of genetically distinct clones.13,14 By using MS16 and msp1F3 to genotype parasite isolates in the present study, we have shown that P. vivax populations in East Sepik and Madang Provinces on the north coast of PNG are extremely genetically diverse.

Samples analyzed in the present study were collected from asymptomatic individuals participating in a cross-sectional study. The typically low-parasite densities of asymptomatic P. vivax infections resulted in PCR being more sensitive for the detection of P. vivax than LM. A greater number of P. vivax samples from East Sepik were detected using LM compared with LDR-FMA (Table 1); however, this might be due to misclassification of some infections by the local microscopists. A third read of the microscopy slides would be required in the case of discrepant results observed from the first two reads (Barnadas C, personal communication). It was previously reported that the MS16 PCR assay was more sensitive than the PCR assay for msp1F3,14 but we observed the opposite; the proportion of samples found to be infected with P. vivax using only msp1F3 was slightly higher (20.3%) than the proportion detected using only MS16 PCR (17%). However, consistent with the higher MS16 diversity reported in this and other studies,13,14 the number of clones detected using the MS16 PCR (N = 375) was slightly higher than the number of clones for msp1F3 (N = 354) (Table 2 and Supplemental Table 1). In addition to the reduced diversity of msp1F3 relative to MS16, the limiting concentrations of template DNA resulting in stochastic amplification of clones may also contribute to the discordant number of clones detected using the two markers.14,36 Despite performing WGA to increase sample volume, the amount of P. vivax DNA in many samples remained at or below the threshold of MS16 and msp1F3 PCR detection.

Very high genetic diversity of a P. vivax population from the Maprik region of East Sepik Province was recently reported.14 This region is approximately 15–20 km northwest of the Wosera catchment, one of four sites from which samples were collected for use in the present study. In Maprik, the diversity of both markers was very high, with MS16 diversity (He = 0.97) higher than the diversity of msp1F3 (He = 0.88).14 No dominant MS16 alleles were detected, whereas detection of three dominant msp1F3 alleles (238, 265, and 276 bp in size) at frequencies > 10% was reported.14 We report here that 238- and 265-bp msp1F3 alleles were also detected at a frequency > 10%; however, the 259-bp allele was detected at a higher frequency (11.76%) than the 276-bp allele (8.68%) (Supplemental Table 1). In both this study and the study by Koepfli and others,14 the 265-bp allele was the most frequently detected msp1F3 allele: a frequency of 24% in Maprik14 and a frequency of 30.8% in the present study. These varying allele frequencies could be caused by slight changes over time. All MS16 alleles were detected at a frequency of less than 4.2% (Supplemental Table 1). Combined, the results of this study and the results of the study by Koepfli and others14 show that P. vivax populations on the north coast of PNG are extremely diverse.

In recent years, there has been a significant decline in the prevalence of P. falciparum infection in the Wosera area.37 This decline is thought to be a result of ongoing malaria studies in the region, heightened awareness of malaria prevention measures, and increased access to treatment. Most importantly, however, the Wosera area was targeted for a community-wide distribution of long-lasting insecticide treatment nets by a local non-governmental agency. As a consequence, > 97% of participants surveyed from the Wosera catchment reported using bed nets. Although bed net usage also ranged from 71% (Mugil catchment) to 98% (Malala catchment) in the Madang areas, the bed nets used there were neither treated nor long lasting (Mueller I and others, unpublished data). In a large cross-sectional survey in East Sepik Province conducted 5 months before the present survey, high bed net coverage was associated with a reduction in prevalence of all four human Plasmodium spp.17 Hence, it is likely that increased insecticide-treated bed net usage has contributed to reduced P. vivax prevalence in East Sepik compared with the Madang villages. Although differences in transmission intensity due to seasonal variations cannot be discounted as samples from East Sepik Province were collected during the dry season and samples from Madang Province were collected in the rainy season, surveys conducted in the Wosera in 2001–2003 prior to the mass distribution of insecticide-treated bednets revealed very little difference in the prevalence of P. falciparum and P. vivax infections between the wet and dry seasons.37 Furthermore, because infection with P. vivax can result in production of latent hypnozoites, P. vivax would be expected to be less sensitive to seasonal variations compared with P. falciparum. Indeed, sympatric populations of P. falciparum surveyed in the same study showed a wider range of infection prevalence among villages of the Wosera (range = 1.7–43.5%).38 Additionally, the villages comprising the three Madang catchments are distributed over a broader geographical area (> 50 km) than those villages of the Wosera (< 10 km).8 Therefore, although likely due to higher coverage of insecticide-treated bed nets, local differences in vector abundance and ecology may also have contributed to differences in relative P. vivax prevalence19 and warrant future investigation.

It is an important observation that, despite the much lower infection prevalence, genetic diversity of the East Sepik P. vivax population was similar to that of the Madang population. A similar observation was recently reported after analysis of P. falciparum infections from the Peruvian Amazon39 and the same areas analyzed in this study.38 For P. vivax, high genetic diversity may be maintained in the face of reduced transmission as a result of the latent hypnozoite stage of the lifecycle, which can remain in the liver for several months and even years.33 Infection with different clones is thought to increase population genetic diversity through meiotic recombination in the mosquito midgut.12,33 Such genetic diversity is essential for parasite fitness and survival, and it is thought that this diversity must be reduced to limit parasite adaptation and population expansion.5,40 Thus, although the implementation of malaria prevention measures seem to have reduced P. vivax prevalence in East Sepik, an even greater reduction in prevalence may be required to decrease population genetic diversity for both P. vivax and P. falciparum.38 The genetic complexity and unique biology of P. vivax infections, coupled with the enormous burden of both species, will present major challenges for malaria elimination in PNG.

Despite the successful implementation of malaria interventions in the East Sepik Province of PNG, a high level of P. vivax genetic diversity was observed, although the infection prevalence was less than one-half that recorded for Madang Province. A similar finding has been observed for sympatric P. falciparum populations.38 High levels of genetic diversity, despite a relatively low infection prevalence in the Wosera, which was sampled during the dry season, show that P. vivax and P. falciparum parasite populations are well-equipped to adapt to a changing local environment and that a significant reduction in transmission intensity will be required to reduce population genetic diversity in highly endemic areas such as PNG. The results of the present study highlight the enormous challenges facing malaria elimination efforts in countries of high malaria endemicity such as PNG.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the ongoing and generous support of the Papua New Guinean communities, particularly the volunteers and their families and the staff of the Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, without whom the study would not have been possible. We would also like to extend our thanks to J. Nale and B. Kiniboro for their involvement in sample collection, T. Adiguma (Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research) for furnishing appropriate sample information, and C. Jennison and R. Keo for database management.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by Project Grants 1003825 and 1010203 from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. J.C.R. was supported by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship. This work was made possible through Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support and Australian Government NHMRC Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme (IRIISS).

Authors' addresses: Alicia Arnott, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, E-mail: alicia@burnet.edu.au. Celine Barnadas and Peter Siba, Papua New Guinea Institute of Medical Research, Goroka, Papua New Guinea, E-mails: celine.barnadas@pngimr.org.pg and Peter.Siba@pngimr.org.pg. Nicolas Senn, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Basel, Switzerland, E-mail: nicolas.senn@gmail.com. Ivo Mueller and Alyssa E. Barry, Division of Infection and Immunity, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute for Medical Research, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, E-mails: mueller@wehi.edu.au and barry@wehi.edu.au. John C. Reeder, Centre for Population Health, Burnet Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, E-mail: jreeder@burnet.edu.au.

References

- 1.Feachem RGA, Phillips AA, Targett GA. Shrinking the Malaria Map: A Prospectus on Malaria Elimination. San Francisco, CA: The Global Health Group, Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galinski MR, Barnwell JW. Plasmodium vivax: who cares? Malar J. 2008;7((Suppl 1)):S9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mueller I, Galinski MR, Baird JK, Carlton JM, Kochar DK, Alonso PL, del Portillo HA. Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:555–566. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerra CA, Howes RE, Patil AP, Gething PW, Van Boeckel TP, Temperley WH, Kabaria CW, Tatem AJ, Manh BH, Elyazar IR, Baird JK, Snow RW, Hay SI. The international limits and population at risk of Plasmodium vivax transmission in 2009. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnott A, Barry AE, Reeder JC. Understanding the population genetics of Plasmodium vivax is essential for malaria control and elimination. Malar J. 2012;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baum J, Billker O, Bousema T, Dinglasan R, McGovern V, Mota MM, Mueller I, Sinden R. A research agenda for malaria eradication: basic science and enabling technologies. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joshi H, Prajapati SK, Verma A, Kang'a S, Carlton JM. Plasmodium vivax in India. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz L, Wapling J, Mueller I, Ntsuke PO, Senn N, Nale J, Kiniboro B, Buckee CO, Tavul L, Siba PM, Reeder JC, Barry AE. Multilocus haplotypes reveal variable levels of diversity and population structure of Plasmodium falciparum in Papua New Guinea, a region of intense perennial transmission. Malar J. 2010;9:336. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joy DA, Gonzalez-Ceron L, Carlton JM, Gueye A, Fay M, McCutchan TF, Su XZ. Local adaptation and vector-mediated population structure in Plasmodium vivax malaria. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1245–1252. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid H, Vallely A, Taleo G, Tatem AJ, Kelly G, Riley I, Harris I, Henri I, Iamaher S, Clements AC. Baseline spatial distribution of malaria prior to an elimination programme in Vanuatu. Malar J. 2010;9:150. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imwong M, Nair S, Pukrittayakamee S, Sudimack D, Williams JT, Mayxay M, Newton PN, Kim JR, Nandy A, Osorio L, Carlton JM, White NJ, Day NP, Anderson TJ. Contrasting genetic structure in Plasmodium vivax populations from Asia and South America. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Eede P, Erhart A, Van der Auwera G, Van Overmeir C, Thang ND, Hung le X, Anne J, D'Alessandro U. High complexity of Plasmodium vivax infections in symptomatic patients from a rural community in central Vietnam detected by microsatellite genotyping. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:223–227. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koepfli C, Mueller I, Marfurt J, Goroti M, Sie A, Oa O, Genton B, Beck HP, Felger I. Evaluation of Plasmodium vivax genotyping markers for molecular monitoring in clinical trials. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1074–1080. doi: 10.1086/597303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koepfli C, Ross A, Kiniboro B, Smith TA, Zimmerman PA, Siba P, Mueller I, Felger I. Multiplicity and diversity of Plasmodium vivax infections in a highly endemic region in Papua New Guinea. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller I, Genton B, Betuela I, Alpers MP. Vaccines against malaria: perspectives from Papua New Guinea. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:17–20. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.1.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization . World Malaria Report: 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller I, Widmer S, Michel D, Maraga S, McNamara DT, Kiniboro B, Sie A, Smith TA, Zimmerman PA. High sensitivity detection of Plasmodium species reveals positive correlations between infections of different species, shifts in age distribution and reduced local variation in Papua New Guinea. Malar J. 2009;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hetzel MW. An integrated approach to malaria control in Papua New Guinea. P N G Med J. 2009;52:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazura JW, Siba PM, Betuela I, Mueller I. Research challenges and gaps in malaria knowledge in Papua New Guinea. Acta Trop. 2012;121:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henry-Halldin CN, Sepe D, Susapu M, McNamara DT, Bockarie M, King CL, Zimmerman PA. High-throughput molecular diagnosis of circumsporozoite variants VK210 and VK247 detects complex Plasmodium vivax infections in malaria endemic populations in Papua New Guinea. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNamara DT, Kasehagen LJ, Grimberg BT, Cole-Tobian J, Collins WE, Zimmerman PA. Diagnosing infection levels of four human malaria parasite species by a polymerase chain reaction/ligase detection reaction fluorescent microsphere-based assay. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:413–421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goudet J. FSTAT (Version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Hered. 1995;86:485–486. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Excoffier L, Lischer HE. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurlbert SH. The non-concept of species diversity: a critique and alternative parameters. Ecology. 1971;52:577–586. doi: 10.2307/1934145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunawardena S, Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Phone-Kyaw M, Pollack RJ, Alifrangis M, Rajakaruna RS, Konradsen F, Amerasinghe PH, Schousboe ML, Galappaththy GN, Abeyasinghe RR, Hartl DL, Wirth DF. Geographic structure of Plasmodium vivax: microsatellite analysis of parasite populations from Sri Lanka, Myanmar, and Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:235–242. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Havryliuk T, Orjuela-Sanchez P, Ferreira MU. Plasmodium vivax: microsatellite analysis of multiple-clone infections. Exp Parasitol. 2008;120:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karunaweera ND, Ferreira MU, Hart DL, Wirth DF. Fourteen polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers for the human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Mol Ecol Notes. 2007;7:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orjuela-Sanchez P, Karunaweera ND, da Silva-Nunes M, da Silva NS, Scopel KK, Goncalves RM, Amaratunga C, Sa JM, Socheat D, Fairhust RM, Gunawardena S, Thavakodirasah T, Galapaththy GL, Abeysinghe R, Kawamoto F, Wirth DF, Ferreira MU. Single-nucleotide polymorphism, linkage disequilibrium and geographic structure in the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax: prospects for genome-wide association studies. BMC Genet. 2010;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinard R, de Winter A, Sarkis GJ, Gerstein MB, Tartaro KR, Plant RN, Egholm M, Rothberg JM, Leamon JH. Assessment of whole genome amplification-induced bias through high-throughput, massively parallel whole genome sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:216. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson TJ, Su XZ, Bockarie M, Lagog M, Day KP. Twelve microsatellite markers for characterization of Plasmodium falciparum from finger-prick blood samples. Parasitology. 1999;119:113–125. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099004552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniels R, Volkman SK, Milner DA, Mahesh N, Neafsey DE, Park DJ, Rosen D, Angelino E, Sabeti PC, Wirth DF, Wiegand RC. A general SNP-based molecular barcode for Plasmodium falciparum identification and tracking. Malar J. 2008;7:223. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van den Eede P, Van der Auwera G, Delgado C, Huyse T, Soto-Calle VE, Gamboa D, Grande T, Rodriguez H, Llanos A, Anne J, Erhart A, D'Alessandro U. Multilocus genotyping reveals high heterogeneity and strong local population structure of the Plasmodium vivax population in the Peruvian Amazon. Malar J. 2010;9:151. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira MU, Karunaweera ND, da Silva-Nunes M, da Silva NS, Wirth DF, Hartl DL. Population structure and transmission dynamics of Plasmodium vivax in rural Amazonia. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1218–1226. doi: 10.1086/512685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Honma H, Kim JY, Palacpac NM, Mita T, Lee W, Horii T, Tanabe K. Recent increase of genetic diversity in Plasmodium vivax population in the Republic of Korea. Malar J. 2011;10:257. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Imwong M, Pukrittayakamee S, Gruner AC, Renia L, Letourneur F, Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Snounou G. Practical PCR genotyping protocols for Plasmodium vivax using Pvcs and Pvmsp1. Malar J. 2005;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koepfli C, Schoepflin S, Bretscher M, Lin E, Kiniboro B, Zimmerman PA, Siba P, Smith TA, Mueller I, Felger I. How much remains undetected? Probability of molecular detection of human plasmodia in the field. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kasehagen LJ, Mueller I, McNamara DT, Bockarie MJ, Kiniboro B, Rare L, Lorry K, Kastens W, Reeder JC, Kazura JW, Zimmerman PA. Changing patterns of Plasmodium blood-stage infections in the Wosera region of Papua New Guinea monitored by light microscopy and high throughput PCR diagnosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:588–596. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry AE, Schultz L, Senn N, Nale J, Kiniboro B, Siba P, Mueller I, Reeder JC. High levels of genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum populations in Papua New Guinea despite variable infection prevalence. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:718–725. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton PL, Torres LP, Branch OH. Sexual recombination is a signature of a persisting malaria epidemic in Peru. Malar J. 2011;10:329. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Havryliuk T, Ferreira MU. A closer look at multiple-clone Plasmodium vivax infections: detection methods, prevalence and consequences. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:67–73. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.