Abstract

Diarrhea is a leading cause of child mortality worldwide. Early recognition of symptoms and referral to medical treatment are essential. In 2007, we conducted a Healthcare Utilization and Attitudes Survey (HUAS) of 1,000 children randomly selected from a population census to define care-seeking patterns for diarrheal disease in Bamako, Mali, in preparation for the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). We found that 57% of caretakers sought care for their child's diarrheal illness from traditional healers, and 27% of caretakers sought care from the government health center (GHC). Weighted logistic regression showed that seeking care from a traditional healer was associated with more severe reported diarrheal disease, like decreased urination (odds ratio [OR] = 3.35, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 1.19–9.41) and mucus or pus in stool (OR = 4.42, 95% CI = 1.35–14.51), along with other indicators of perceived susceptibility. A locally designed traditional healer referral system was, therefore, created that emphasized more severe disease. This system may serve as a model for health systems in West Africa.

Introduction

Diarrheal disease is a leading cause of child mortality worldwide, with 25% of deaths in Africa and 31% of deaths in South Asia attributed to diarrhea among children aged 1 month to 5 years.1 Early recognition of dehydration, use of effective home remedies, and timely referral to appropriate medical treatment are crucial for preventing diarrheal mortality.2 Few population-based epidemiologic studies of healthcare use patterns for childhood diarrhea have previously been conducted in Mali,3–5 and to our knowledge, none have been conducted thus far in the capital city, Bamako.

We conducted a Healthcare Utilization and Attitudes Survey (HUAS) in Bamako from March to May of 2007 to define the healthcare-seeking landscape in preparation for the case control component of the Global Enteric Multicenter Study-1 (GEMS-1)6 undertaken to address the burden and etiology of moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) in four representative sites in sub-Saharan Africa and three sites in South Asia7,8 using a common HUAS protocol and survey tool.9 Children < 5 years of age were randomly selected from the demographic surveillance system (DSS) maintained by the Centre pour le Développement des Vaccins du Mali (CVD-Mali), and their primary caretakers were interviewed. The HUAS was followed by several subsequent abbreviated surveys (dubbed HUAS-lite) that were initiated in 2009 and conducted with each DSS round for the remainder of the GEMS-1 study. Recognizing that enrollment of MSD cases and controls would occur at only a few representative sentinel health centers (SHCs) during GEMS-1 and that extrapolations would have to be made to estimate overall MSD incidence and pathogen-specific incidences for the entire DSS population < 5 years of age, the baseline HUAS was critical in guiding where to establish enrollment SHCs that would maximize the yield of MSD cases for the GEMS-1 case control study given budgetary constraints. The baseline HUAS and the subsequent HUAS-lite data also provided the information to allow extrapolations of numbers of cases and incidence rates to the relevant age groups in the entire DSS population. The data generated by the HUAS and HUAS-lites also enabled statistical analysis of diarrhea and types of healthcare-seeking behaviors as outcomes, which will be the primary focus of this paper.

Methods

Setting and study sample.

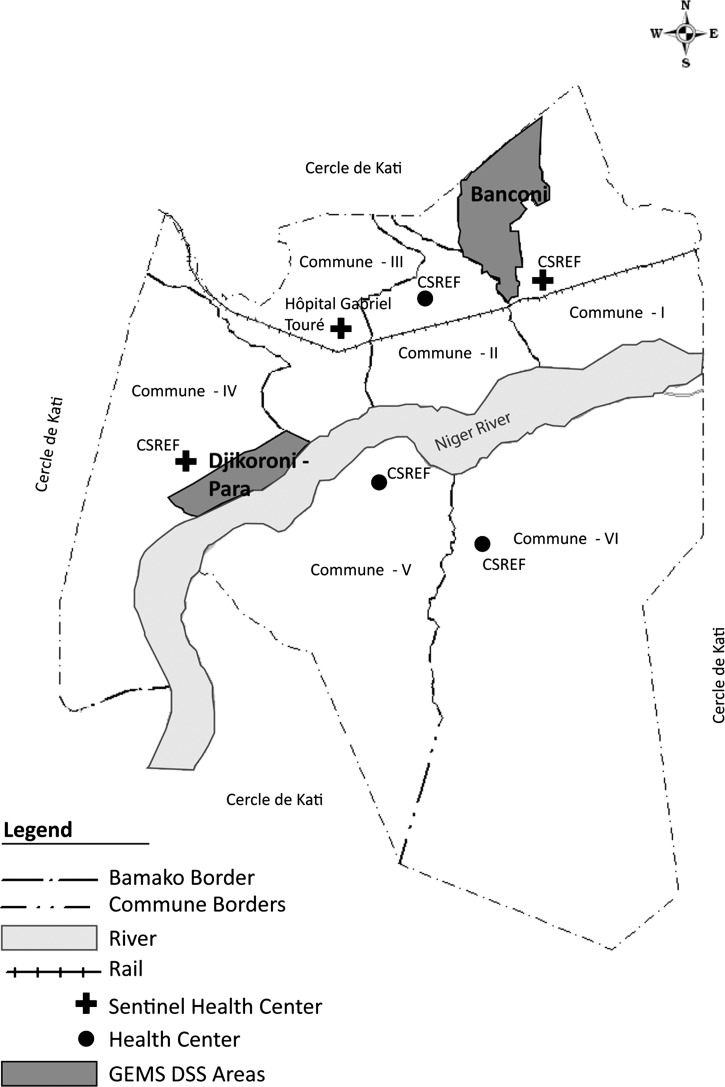

Mali is a large, land-locked, largely arid, mostly Muslim country in West Africa. A cross-sectional HUAS was conducted in Bamako, Mali (Figure 1)10 from March 9 to May 12, 2007 in a DSS administered by CVD-Mali. The DSS comprises the Djikoroni-para quartier (Supplemental Figure 1)11 of Commune IV (population = 82,312, < 5 years population = 11,864) and the Banconi quartier (Supplemental Figure 2)12 of Commune I (population = 122,352, < 5 years population = 20,039). The population density of Banconi is 8,110 persons/km2, whereas the population density of Djikorini-para is 21,095 persons/km2, making it more densely populated than New York City.13 The combined population density for the study area in Bamako is 12,832/km2. The population of these quartiers largely subsists on small business activity, trading, foreign remittances, and government employment.

Figure 1.

Map of Bamako, Mali, showing the GEMS DSS areas and SHCs selected for the GEMS. The SHCs within the DSS areas are named in Supplemental Figures 1 and 2.

Sample size.

Refer to the HUAS overview work for more information on sample size.9

Data management.

Refer to the HUAS overview work for more information on data management.9

Survey tools.

The HUAS survey tool was a questionnaire designed to collect information on sociodemographics, parental perception of illness, use of healthcare facilities, and child morbidity. A detailed history of diarrhea (three or more abnormally loose stools during a 24-hour period) in the previous 2 weeks was taken, and information was collected on home and healthcare center management of the child's diarrheal illness, healthcare expenses, and attitudes to healthcare and diarrhea.9 The HUAS-lite survey tool was similar to the HUAS, except that it included an abbreviated list of questions asked only of caretakers reporting that their child had diarrhea within the previous 2 weeks.9 Meetings were held with staff and community leaders before the launch of the study to agree on how various terms and phrases would be expressed in Bambara (local language) in the study questionnaire. A questionnaire that had been translated from English to French to Bambara (the language of the interviews) was then pre-tested.

Ethical statement.

The consent forms and protocol, including the provision for oral consent, were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculté de Médicine, de Pharmacie et d’Ondoto-Stomatologie (FMPOS) of the University of Bamako and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD.

Community interviewers went to the households of selected children, and they attempted to identify the children and interview their primary caretakers using a standardized questionnaire. An audio cassette in Bambara describing all aspects of the study and providing an audible reading of the consent form was played for caretakers as part of the informed consent process. Caretakers were asked if they had questions, and questions were answered to ensure that the protocol was understood. If the caretakers agreed to participate, written consent was obtained from caretakers who said that they could read confidently enough to understand the consent form (< 30% of primary caretakers who agreed to participate). Caretakers who said that they could not read confidently enough to understand the consent form signed the consent form using either a personal sign or a left index fingerprint. Consent forms of caretakers who said that they could not read were also signed by a literate witness to the consent process (e.g., a neighbor or another adult household member who was not a caretaker). The community interviewers then administered the questionnaire in Bambara.

Participating caretakers.

Of 1,263 children who were randomly selected from the DSS database of all individuals living in the DSS area to have their caretaker interviewed, 141 children were not present at the time of the household visit or could not be located at the address provided (family outmigration), and 10 children had died; 112 children were found to be aged ≥ 60 months. Therefore, there were 1,000 children whose caretakers could be approached. All caretakers (100%) of these children agreed to be interviewed, thereby providing data for analysis. There were 246 children in the 0–11 months age group, 363 children in the 12–23 months age group, and 391 children in the 24–59 months age group. Although the HUAS questionnaire was conducted over a relatively short period of time, the HUAS-lite was integrated into the DSS round, and interviews were deliberately spaced out evenly across the round to avoid bias by short-term temporal events,9 such as Rotavirus outbreaks.14

Data analysis.

All percentages and logistic regressions were age- and sex-weighted to the DSS population9 unless otherwise indicated. Confidence intervals for survey-weighted proportions were derived using Taylor-linearized variance estimates15 using the default vce(linearized) option in Stata. Descriptive multivariate models were built for the diarrhea and care-seeking outcomes. Wald testing was used to select the exposure variables for the model by adding and removing variables to determine which were statistically significantly associated with the outcome and stable in the presence of other variables. After variables of interest were identified, we assessed for confounding by age, sex, and socioeconomic status by wealth index9 as well as the presence of effect modification by adding interaction terms. Categories of various intervals were created for continuous variables, such as age and wealth index, to determine whether the variables were associated with the outcome in a non-linear and/or non-continuous fashion. Using the estat gof command in Stata, the F-adjusted mean residual test for goodness of fit for logistic regression models fitted using survey data was used to determine a final selection of variables that provided the best fit.16

For the examination of factors associated with seeking care from a traditional healer, variables were separated into concepts corresponding to the Health Belief Model for analytical clarity and ease of interpretation (Supplemental Tables 1–5)17: perceived susceptibility to diarrhea, perceived severity of diarrhea, perceived benefits of seeking care for diarrhea, perceived barriers to seeking care for diarrhea, and self-efficacy for treating, preventing, or seeking care for diarrhea (there were no variables in our questionnaire corresponding to cues to action).17

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). The level of significance used in all statistical tests was 0.05.

Results

Caretakers reported that 126 of 1,000 children had experienced an episode of diarrhea within the previous 2 weeks (Table 1). When stratified by age group, the numbers with diarrhea were sparse and particularly low among children in the oldest age group (26/391). When viewed by MSD status, the numbers were even more sparse. Exploratory data analysis showed that the numbers were too low for meaningful regression analysis. Therefore, the age groups were combined for analysis, and diarrhea was used as the outcome of interest rather than MSD.

Table 1.

Number of children enrolled reporting diarrhea within the previous 2 weeks and MSD within the previous 2 weeks by age group

| Age stratum (months) | Enrolled (n) | Diarrhea in previous 2 weeks | MSD in previous 2 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percent (weighted) | b | Percent (weighted) | ||

| 0–11 | 246 | 44 | 18 | 26 | 11 |

| 12–23 | 363 | 56 | 15 | 37 | 10 |

| 24–59 | 391 | 26 | 7 | 16 | 4 |

| Combined | 1,000 | 126 | 12 | 79 | 7 |

Fewer children ages 0–11 months were enrolled than the older age groups (Table 1); approximately one-half were female, and the primary caretaker was the respondent for the vast majority (Table 2). Educational attainment was low for the primary caretakers, with only 17% having completed primary school. Household size in Mali is large (median size = 13 members) because of a tradition of multiple generations living together. Children with diarrhea did not seem to be different from the overall sample when viewed by background and household characteristics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Background and household characteristics of children in the HUAS study population, Bamako, 2007 (N = 1,000)

| Characteristic | All interviewed (N = 1,000) | Children with diarrhea in the preceding 2 weeks (N = 126) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | Percent* | n/N | Percent* | |

| Age stratum (months) | ||||

| 0–11 | 246 | 25 | 44 | 35 |

| 12–23 | 363 | 36 | 56 | 44 |

| 24–59 | 391 | 39 | 26 | 21 |

| Female sex | 508 | 51 | 58 | 46 |

| Primary caretaker is a parent | 926 | 93 | 121 | 96 |

| Mother lives in household | 961 | 96 | 123 | 98 |

| Father lives in household | 72 | 83 | 97 | 77 |

| Primary caretaker completed primary school or above | 169 | 17 | 20 | 16 |

| Median number (range) of people living in household for past 6 months | 13 (3–100) | 13 (3–90) | ||

| Median number (range) of rooms in house for sleeping | 4 (1–82) | 4 (1–18) | ||

| Median number (range) of children ages < 60 months living in house | 2 (1–14) | 2 (1–14) | ||

Unweighted.

Proportion of children with MSD within the previous 2 weeks seeking care at SHCs.

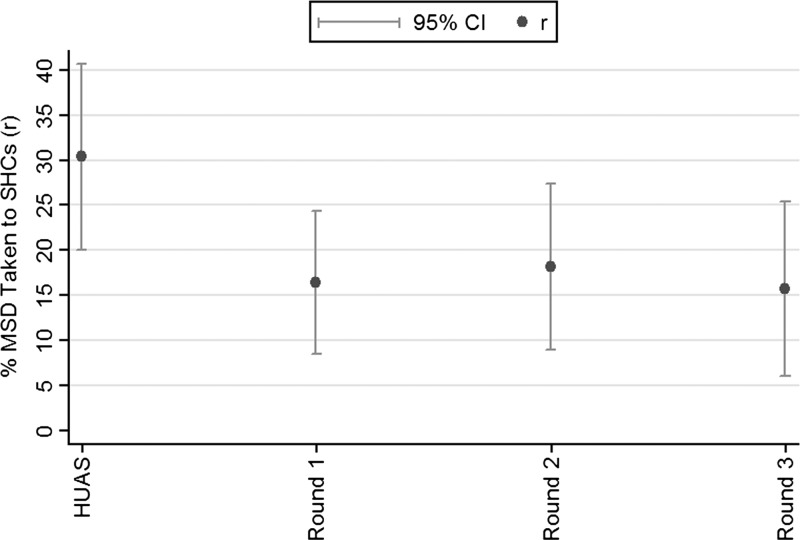

The SHCs selected for the GEMS were ASACOBA, Infirmerie du Camp Para, ASACODJAN, Center de Santé Sadja, and Center de Santé Cherifla from Banconi (Supplemental Figure 1); ASACODJIP and ASACODJENEKA from Djikoroni-para (Supplemental Figure 2); and CSREF Commune IV, Hôpital Gabriel Touré, and CSREF Commune I from outside the DSS areas (but serving large numbers of DSS residents) (Figure 1). The proportion seeking care from an SHC for the original HUAS was 29.6% (95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 18.5–40.6) (Figure 2 and Table 3). However, the proportion was lower for each round of the subsequent HUAS-lite, probably because of the design of the HUAS-lite9; it was intentionally spread throughout the DSS round to avoid capturing seasonal anomalies in pathogen-specific incidence such as rotavirus outbreaks,14 possible time-specific differences in care-seeking behavior because of large variations in real income, or available time associated with agricultural season18 or other unknown factors. Because of their superior design for capturing this proportion, a combined proportion was calculated for the HUAS-lite but not the HUAS (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Percent of children with MSD taken to an SHC for the HUAS and subsequent HUAS-lite rounds.

Table 3.

Proportion of children with MSD seeking care from an SHC

| HUAS round | Start | End | < 5 Years population | Interviewed | Diarrhea in previous 2 weeks | Diarrhea taken to SHC | MSD in previous 2 weeks | MSD taken to SHC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percent (95% CI) | n | Percent (95% CI) | n | Percent (95% CI) | n | Percent (95% CI) | |||||

| Original | 3/9/07 | 5/12/07 | 33,220 | 1,000 | 126 | 12 (10–14) | 28 | 21.2 (14–29) | 79 | 7 (6–9) | 24 | 30 (19–41) |

| Lite 1 | 2/24/09 | 9/3/09 | 31,923 | 1,016 | 185 | 14.8 (13–17) | 22 | 12 (6–17) | 94 | 7 (6–9) | 17 | 16 (9–24) |

| Lite 2 | 11/10/09 | 5/31/10 | 32,526 | 1,001 | 157 | 12.1 (10–14) | 24 | 13 (8–18) | 67 | 5 (4–6) | 14 | 18 (9–27) |

| Lite 3 | 8/8/10 | 1/15/11 | 32,014 | 998 | 164 | 13.1 (11–15) | 19 | 10 (5–16) | 79 | 6 (4–8) | 14 | 16 (6–25) |

| Combined* | – | – | – | 3,013 | 506 | 13 (12–15) | 65 | 12 (9–15) | 240 | 6 (5–7) | 45 | 17 (12–22) |

Combined is for HUAS-lite rounds only.

Factors associated with diarrheal illness.

On simple weighted logistic regression, being younger was more strongly associated with reported diarrhea within the previous 2 weeks (Supplemental Table 6). Monthly increments of age as a continuous variable were associated with decreased odds of diarrhea (odds ratio [OR] = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.95–0.97). If the caretaker was a parent, there was a threefold greater odds of reported diarrhea compared with a non-parent respondent (OR = 3.03, 95% CI = 1.1–8.36).

The final multivariate descriptive model showed that being a girl, being from a relatively wealthy family, having an uneducated caretaker, and claiming to know ways to prevent simple diarrhea were all negatively associated with reporting an episode of diarrhea (Table 4). A linear spline function showed that increasing increments of age were positively associated with diarrhea up to 9 months of age but negatively associated with diarrhea for children 9 months or older. Although age was associated with the outcome, it did not confound the association of any of the other variables in the final model with the outcome. Other factors that were positively associated with diarrhea in the multivariate model were additional children < 60 months of age living in the household and believing that nutrition could be used to prevent diarrhea.

Table 4.

Multivariate weighted logistic regression showing factors associated with reported diarrheal illness within the previous 14 days among children < 5 years old in the HUAS, Bamako, 2007 (N = 1,000)

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age (months), less than 9 months | 1.31 | 1.10–1.56 |

| Age (months), 9 months and over | 0.94 | 0.92–0.96 |

| Female | 0.78 | 0.51–1.20 |

| Wealth index (highest two quintiles) | 0.60 | 0.38–0.95 |

| Children < 60 months old living in the household | 1.02 | 1.01–1.20 |

| Caretaker had no education (compared with religious, primary, secondary, or post-secondary) | 0.61 | 0.39–0.95 |

| Caretaker knows ways to prevent the child from getting simple loose/watery diarrhea | 0.34 | 0.20–0.58 |

| Caretaker believes nutrition is one of the best ways to prevent diarrhea | 1.89 | 1.08–3.31 |

Seeking care outside the home.

Among 96 caretakers who sought care for their child outside the home, 27.3% visited a government health center (GHC), 17.2% sought care from a pharmacy, 10.6% bought a remedy from a market vendor, 5.3% sought care from an unlicensed practitioner, and 1.7% sought care from a licensed practitioner (Table 5). None reported seeking care from friends or relatives. Importantly, we found that 56.9% of caretakers sought for care from a traditional healer for their child's diarrheal episode. Moreover, 48.3% sought care from a traditional healer and did not subsequently go on to seek care from a GHC.

Table 5.

Care-seeking behavior among caretakers with children with diarrhea in the HUAS study population, Bamako, 2007 (N = 96)

| Characteristic: Type of care sought | Caretaker who sought care for child with diarrhea in the preceding 2 weeks (N = 96) | |

|---|---|---|

| n | Weighted (%) | |

| Pharmacy | 16 | 17 |

| Friend/relative | 0 | 0 |

| Traditional healer | 53 | 57 |

| Before seeking care at GHC | 5 | 5 |

| Without seeking care at GHC | 45 | 48 |

| Unlicensed practitioner* | 5 | 5 |

| Licensed practitioner/private doctor (not at a hospital) | 3 | 2 |

| Bought remedy in shop/market | 10 | 11 |

| GHC | 28 | 27 |

Unlicensed practitioner/village doctor/bush doctor/village health worker.

Factors associated with seeking care from a traditional healer.

Simple weighted logistic regression showed that, among indicators of perceived susceptibility (Supplemental Table 1), caretakers who looked for coma/loss of consciousness as an indicator of dehydration had a 5.16 higher odds (95% CI = 1.24–21.49) of taking their child to a traditional healer for diarrhea compared with other sources of care. Among indicators of perceived susceptibility (Supplemental Table 2), caretakers reporting decreased urination associated with the diarrheal episode had a 3.46 times greater odds (95% CI = 1.27–9.42) of seeking care from a traditional healer compared with other sources of care. Neither the perceived benefits (Supplemental Table 3) nor the perceived barriers (Supplemental Table 4) were associated with seeking care from a traditional healer.

Multivariate weighted logistic regression yielded a final model (Table 6) with decreased urination (OR = 3.34, 95% CI = 1.19–9.41) and mucus or pus in the stool (OR = 4.42, 95% CI = 1.35–14.51) showing a strong positive association with seeking care from a traditional healer along with caretaker's belief that coma (OR = 10.37, 95% CI = 1.09–98.41) and thirst (OR = 3.55, 95% CI = 1.12–11.16) are indicators of dehydration. The belief that wrinkled skin was an indicator of dehydration was negatively associated with seeking care from a traditional healer (OR = 0.14, 95% CI = 0.04–0.52). No other variables, including age, sex, or socioeconomic status, were associated with or acted as confounders of the associations above.

Table 6.

Multivariate weighted logistic regression showing factors associated with seeking care from a traditional healer (versus all other sources of care) for reported diarrheal illness within the previous 14 days among children < 5 years old in the HUAS, Bamako, 2007 (N = 96)

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Signs/symptoms | ||

| Caretaker thought that the child had decreased urination | 3.35 | 1.19–9.41 |

| Caretaker reported mucus or pus in the stool | 4.42 | 1.35–14.51 |

| Beliefs | ||

| Caretaker thinks wrinkled skin is a sign of dehydration | 0.14 | 0.04–0.52 |

| Caretaker thinks coma is a sign of dehydration | 10.37 | 1.10–98.41 |

| Caretaker thinks thirst is a sign of dehydration | 3.55 | 1.14–11.16 |

Discussion

This research has defined the patterns of healthcare use and attitudes to diarrheal illness as well as identified some risk factors associated with reported diarrhea in Bamako, Mali in 2007–2011. The main finding was that traditional healers were the main source of care for children with diarrheal illness. Moreover, for children with diarrhea, seeking care from a traditional healer was positively associated with some (although not all) reported symptoms of clinically more severe disease, positively associated with beliefs regarding erroneous, unreliable, or extreme signs of dehydration (coma/loss of consciousness and thirst), and negatively associated with correctly identifying wrinkled skin as a sign of dehydration. Our multivariate analysis of diarrhea as an outcome yielded contradictory results, including the finding that the caretaker believing she knows ways to prevent simple loose/watery diarrhea was negatively associated with diarrhea, whereas believing nutrition was one of the best ways to prevent diarrhea was positively associated with diarrhea (Table 4).

The proportion of caretakers seeking care for their children's diarrheal illness from traditional healers (57%) was much higher than the proportion of those caretakers seeking care from a GHC (27%) or a licensed practitioner (2%). Use of traditional healers and medicines has been on the rise since 199419 after the West African currency (CFA) was devalued by 50% relative to the French Franc, leading to higher prices for consumer products, especially pharmaceuticals, almost all of which are imported.20 A qualitative study of home management of childhood diarrhea, conducted in 2003 in nearby Bougouni district, found that care-seeking from traditional healers was common and often sought in tandem with modern medicine.5 The study also noted that some severe forms of diarrheal illness were more likely to be ascribed to supernatural causes and therefore, treatable only by traditional healers, a finding that was corroborated by our research (Table 6), where we found that reported decreased urination and mucus or pus in the stool were positively associated with seeking care from a traditional healer.5 Similarly, seeking care from a traditional healer was positively associated with the belief that coma/lack of consciousness is sign of dehydration, perhaps reflecting a casual attitude to what is a sign of severe disease. It is difficult to interpret the positive association between seeking care from a traditional healer and the belief that thirst was a sign of dehydration, because the questionnaire did not specify the degree of thirst; it is necessary to know, because thirst can suggest some dehydration or severe dehydration as per the World Health Organization assessment guidelines.21 Notwithstanding the interpretation above, thirst and coma/lack of consciousness are both bona fide signs of dehydration,21 and the caretakers were not mistaken to name them, perhaps indicating the role of traditional healers as a routine, primary source of medical care.

The belief that wrinkled skin is a sign of dehydration21,22 was negatively associated with seeking care from a traditional healer in our multivariate model. As with thirst, however, we did not collect information on the degree of lack of skin turgor, making it unclear if this question reflects some dehydration or severe dehydration.21 We speculate that, because this sign is not an intuitive sign of dehydration (unlike thirst), this belief may reflect a higher degree of health education, which leads to seeking care from a health center rather than a traditional healer.

The Bougouni researchers also noted that the traditional healers themselves viewed their role as complementary with the government health system and voiced readiness to cooperate if they believed more appropriate therapies (such as zinc) were available for diarrheal disease. This willingness of traditional healers to cooperate was also observed in Bamako and leveraged by our study to create an active referral system to ensure that children brought to traditional healers with diarrhea were also brought to health centers for treatment.

We were initially puzzled by our observation that cases with signs of severe or complicated disease were more likely to be taken to traditional healers rather than other sources of care where modern Western style clinical diagnostic methods and treatments were available (Table 6). The qualitative study conducted in Bougouni helped to clarify this care-seeking behavior by Malian mothers and child caretakers. In Bougouni, the most serious and life-threatening cases of diarrhea were more often attributed to supernatural causes (such as a spirit or evil eye) and therefore (according to the beliefs of the mother), more appropriately treated by traditional healers.5 The factors associated with referral to a traditional healer in Bamako fell entirely within the perceived susceptibility and perceived severity concepts (which together constitute perceived threats under the Health Belief Model [HBM]23). This observation suggests that any attempted intervention to ensure that children receive adequate care for diarrheal disease must focus on either changing a caretaker's cultural beliefs regarding the nature of threats and the actions taken to address those threats or intervening on a more manageable scale with traditional healers. Viewed in this light, we began to see the traditional healers as a potential referral network.

Our multivariate model also showed that certain beliefs regarding how to detect dehydration, which we categorized within the perceived susceptibility rubric of the HBM, were also associated with seeking care from a traditional healer (Table 6). Those caretakers who looked for coma/lack of consciousness, which is a severe, possibly life-threatening sign of severe dehydration, were much more likely to seek care from a traditional healer. Those caretakers who looked for thirst, which is a more intuitive sign of dehydration, were also more likely to seek care from a traditional healer. However, those caretakers who looked for wrinkled skin, a less intuitive sign that may indicate exposure to health education, were less likely to take the child to a traditional healer. This finding may reflect both the accepted role of the traditional healer in treating severe symptoms caused by supernatural causes, which was found in Bougini,3,5 and also a trust or exposure to Western-style medical treatment among other parents.

Our multivariate model of diarrhea outcome showed that increasing monthly increments of age were positively associated with diarrhea for children < 9 months but negatively associated for children ≥ 9 months (Table 4), which is consistent with results of previous studies.24 Being a girl was negatively associated with reported diarrhea, reflecting a similar finding in Guinea-Bissau,25 where researchers found that Cyrptosporidium-associated diarrhea was even more strongly associated with male sex.26 Other studies are inconsistent on an association between sex and diarrhea; however, we speculate that this association may alternatively be because of sex-specific recall bias.

Odds of diarrheal disease were higher for every additional child < 60 months of age living in the household, which is expected, because crowding is known to be a risk factor for diarrheal illness.27,28 Belonging to the highest two quintiles of wealth is also associated with lower odds of diarrheal illness, which again, is expected, because poor socioeconomic status operates on multiple pathways to increase risk of exposure.29 Caretaker report of knowing ways to prevent simple loose or watery diarrhea was negatively associated with reported diarrhea within the previous 2 weeks, suggesting that this belief reflected actual actionable knowledge. By contrast, a belief that nutrition was the best way to prevent diarrhea was positively associated with recalled illness, perhaps reflecting ignorance of more effective measures (Table 4). We did not expect, however, that having a caretaker with no education would be associated with lower odds of reported diarrheal disease compared with having a caretaker with at least some education (Table 4). We speculate that educated respondents may be better at recalling history of diarrheal illness. Such differential reporting by educational status could result in other putative risk factors that are closely associated with educational status seeming to be associated with diarrhea more strongly than they truly are; conversely, factors associated with lack of education may seem to be less strongly associated, not associated, or even negatively associated with diarrhea. None of the factors identified as being associated with diarrhea in our multivariate model was an obvious candidate for this type of bias, but there may have been variables that were rendered null by such a bias and therefore, would not have been identified by our study.

Limitations.

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of this study. First, the HUAS questionnaire was designed for a seven-site multicenter study and not tailored with the detailed questions on attitudes to traditional healers that would have been optimal in Bamako. Second, the questions asked in the HUAS were not specifically designed to be used for complex analysis of diarrhea or choice of traditional healer as an outcome. As such, we believe that the broad thrusts of the concepts represented by the questions are more useful than the questions themselves. For example, if factors associated with perceived susceptibility are identified as being associated with seeking care with a traditional healer, then this finding may suggest that perceived susceptibility may be a target for behavioral intervention rather than the specific variable itself. The HBM framework was selected for interpretation of the traditional healer outcome, in part because it allowed us to examine broad concepts and their associations with the outcome rather than the specific questions asked, which may only have a tendentious logical connection to the outcome. Third, the possibility of recall bias by educational status suggested by the negative association that we observed between lack of education and diarrhea raises the possibility that our calculation of the proportion of children seeking care from an SHC could be biased away from the null if the pool of more educated caretakers of whom this question is being asked are more likely to seek care from an SHC.

The GEMS Traditional Healer Referral System.

When it became clear that the majority of caretakers of pediatric diarrhea cases was seeking care from traditional healers (Table 5), we undertook to create a referral system based around traditional healers in Bamako. This undertaking was reinforced by the Bougouni study,5 which observed that care-seeking behavior from traditional healers was often sought together with modern medical care and that traditional healers themselves were open to the idea of integrating medical therapies like zinc into their own treatment regimens or referring children with diarrhea for medical care at GHCs.5 A series of meetings were, therefore, held between the local Malian GEMS leadership, Ministry of Health representatives, and the Syndicate of Traditional Healers in Bamako to craft a referral plan that would be acceptable to traditional healers but also ensure that children with diarrhea and (especially) MSD were referred to GHCs for appropriate treatment. Through these meetings, it became clear that the following criteria would have to be satisfied.

-

(1)

The incomes of traditional healers could not be endangered.

-

(2)

Traditional healers had to be seen by the mothers as playing a role in caring for their children, and that role could not be undermined.

-

(3)

Only trained medical personnel could verify the severity of diarrheal cases, and therefore, it was important that all cases be referred.

Using the above guiding criteria, a plan was made to create a two-tiered payment system, informed by the HUAS observations and affirmed by the traditional healers, that would compensate traditional healers for foregone revenues (i.e., earnings that they would have gained by treating the children themselves) but not reward them excessively. To encourage the referral of severe cases, which were considered the purview of traditional healers, the compensation was set at 500 CFA (US $1) for a referred diarrhea case, but 1,000 CFA for a severe case (actual diarrhea status and severity would be determined at the GHC).

A study on care-seeking behavior for diarrhea among children under age 5 years in neighboring Niger intentionally overlooked traditional healers, classifying them as if the caretaker had not sought care. In so doing, the study may have missed an opportunity to identify a valuable healthcare referral network.30 Our referral system has been in operation in our DSS area in Bamako since April of 2009, and it has been well-accepted by traditional healers and Ministry of Health officials. Similar schemes have been explored elsewhere in Africa for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),31 malaria,32 and blindness.33 However, our Bamako scheme is unusual in that it provides a small monetary compensation to counteract what would otherwise be foregone revenue for the traditional healer. We believe that this method is desirable, because schemes that do not provide compensation for the healer may not be sustainable.

Over the course of the GEMS-1 study, 895 children were referred through the traditional healer referral network, of which 548 children had MSD. Given our findings (Table 5), we can speculate that the majority of these children would not have been referred otherwise, and therefore, our referral system may have prevented a substantial number of negative outcomes associated with MSD, such as dehydration, persistent diarrhea,34 and death.35,36

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the caretakers and children who participated in this study and the management and staff of the Mali Ministry of Health institutions for their support. We are grateful to the doctors, nurses, and field staff of the Center for Vaccine Development—Mali for their hard work and professionalism, thereby making this research possible despite challenging conditions. We also thank the traditional healers for helping us to better serve the health needs of the children of Bamako. We especially thank Kousick Biswas, Rebecca “Anne” Horney, Christina Carty, Carla Davis, and the other staff of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Data Coordinating Center for their help with data management and Susan J. Conway for the hours of work that she put into perfecting the maps of Bamako, Djikoroni-para, and Banconi.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by Grant #38874 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (M.M.L., principal investigator).

Authors' addresses: Tamer H. Farag, Karen L. Kotloff, and Myron M. Levine, Center for Vaccine Development, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, E-mails: tfarag@medicine.umaryland.edu, kkotloff@medicine.umaryland.edu, and mlevine@medicine.umaryland.edu. Uma Onwuchekwa, Sanogo Doh, and Samba O. Sow, Center for Vaccine Development—Mali, Bamako, Mali, E-mails: uonwuche@medicine.umaryland.edu, sanogodoh@yahoo.fr, and ssow@medicine.umaryland.edu. Anna Maria Van Eijk, Child and Reproductive Health Group, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, United Kingdom, E-mail: amvaneijk@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Walker CL, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE. Estimating diarrhea mortality among young children in low and middle income countries. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, UNICEF, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USAID . Implementing the New Recommendations on the Clinical Management of Diarrhoea. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winch PJ, Gilroy KE, Doumbia S, Patterson AE, Daou Z, Diawara A, Swedberg E, Black RE, Fontaine O. Mali Zinc Pilot Intervention Study Group Operational issues and trends associated with the pilot introduction of zinc for childhood diarrhoea in Bougouni district, Mali. J Health Popul Nutr. 2008;26:151–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halvorson SJ, Williams AL, Ba S, Dunkel FV. Water quality and waterborne disease in the Niger River Inland Delta, Mali: a study of local knowledge and response. Health Place. 2011;17:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis AA, Winch P, Daou Z, Gilroy KE, Swedberg E. Home management of childhood diarrhoea in southern Mali–implications for the introduction of zinc treatment. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:701–712. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotloff KL, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Nataro JP, Farag TH, van Eijk A, Adegbola RA, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Saha D, Sow SO, Sur D, Zaidi AK, Biswas K, Panchalingam S, Clemens JD, Cohen D, Glass RI, Mintz ED, Sommerfelt H, Levine MM. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55((Suppl 4)):S232–S245. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levine MM, Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Muhsen K. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS): impetus, rationale, and genesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55((Suppl 4)):S215–S224. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farag TH, Nasrin D, Wu Y, Muhsen K, Blackwelder WC, Sommerfelt H, Panchalingam S, Nataro JP, Kotloff KL, Levine MM. Some epidemiologic, clinical, microbiologic, and organizational assumptions that influenced the design and performance of the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55((Suppl 4)):S225–S231. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasrin D, Wu Y, Blackwelder WC, Farag TH, Saha D, Sow SO, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Sur D, Faruque ASG, Zaidi AKM, Biswas K, Van Eijk AM, Walker DG, Levine MM, Kotloff KL. Health care seeking for childhood diarrhea in developing countries: evidence from seven sites in Africa and Asia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89((Suppl 1)):3–12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Statistics—Mali . Map of Bamako Showing GEMS DSS Areas. Bamako, Mali: National Institute of Statistics (INSTAT)—Mali; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.PDSU . Map of Djikoroni-para. Bamako, Mali: PDSU; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.PDSU . Map of Banconi. Bamako, Mali: PDSU; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.United States Census Bureau . State and County QuickFacts 2010. United States Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levy K, Hubbard AE, Eisenberg JN. Seasonality of rotavirus disease in the tropics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:1487–1496. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lohr SL. Variance estimation in complex surveys. In: Michelle Julet SS, editor. Sampling: Design and Analysis. 2nd Ed. Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Archer KJ, Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW. Goodness-of-fit tests for logistic regression models when data are collected using a complex sampling design. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2007;51:4450–4464. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 3rd Ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oumou CM. The Impact of Seasonal Changes in Real Incomes and Relative Prices on Households' Consumption Patterns in Bamako, Mali. Michigan State University; 2004. pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balzar J. In Mali, lizard blood may fix what ails you. LA Times. 1995. August 19, 1995. http://articles.latimes.com/1995-08-19/news/mn-36723_1_traditional-medicine Available at. Accessed December 20, 2012.

- 20.Noble K. French devaluation of African currency brings wide unrest. New York Times. 1994. February 3, 1994.

- 21.World Health Organization . The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS. Is this child dehydrated? JAMA. 2004;291:2746–2754. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:175–183. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Molbak K, Jensen H, Ingholt L, Aaby P. Risk factors for diarrheal disease incidence in early childhood: a community cohort study from Guinea-Bissau. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:273–282. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molbak K, Aaby P, Hojlyng N, da Silva AP. Risk factors for Cryptosporidium diarrhea in early childhood: a case-control study from Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:734–740. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahman M, Rahaman MM, Wojtyniak B, Aziz KM. Impact of environmental sanitation and crowding on infant mortality in rural Bangladesh. Lancet. 1985;2:28–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alam N, Wojtyniak B, Henry FJ, Rahaman MM. Mothers' personal and domestic hygiene and diarrhoea incidence in young children in rural Bangladesh. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;18:242–247. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeager BA, Lanata CF, Lazo F, Verastegui H, Black RE. Transmission factors and socioeconomic status as determinants of diarrhoeal incidence in Lima, Peru. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1991;9:186–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page AL, Hustache S, Luquero FJ, Djibo A, Manzo ML, Grais RF. Health care seeking behavior for diarrhea in children under 5 in rural Niger: results of a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:389. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kayombo EJ, Uiso FC, Mbwambo ZH, Mahunnah RL, Moshi MJ, Mgonda YH. Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makundi EA, Malebo HM, Mhame P, Kitua AY, Warsame M. Role of traditional healers in the management of severe malaria among children below five years of age: the case of Kilosa and Handeni Districts, Tanzania. Malar J. 2006;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courtright P, Chirambo M, Lewallen S, Chana H, Kanjaloti S. Collaboration with African Traditional Healers for the Prevention of Blindness. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black RE, Brown KH, Becker S, Abdul-Alim ARM, Huq I. Longitudinal studies of infectious diseases and physical growth in rural Bangladesh. II. Incidence of diarrhea and association with known pathogens. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;115:315–324. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butler T, Islam M, Azad AK, Islam MR, Speelman P. Causes of death in diarrhoeal diseases after rehydration therapy: an autopsy study of 140 patients in Bangladesh. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:317–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutta P, Mitra U, Rasaily R, Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya MK, Manna B, Gupta A, Kundu B. Assessing the cause of in-patients pediatric diarrheal deaths: an analysis of hospital records. Indian Pediatr. 1995;32:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.