Abstract

Diarrhea causes 16% of all child deaths in Pakistan. We assessed patterns of healthcare use among caretakers of a randomly selected sample of 959 children ages 0–59 months in low-income periurban settlements of Karachi through a cross-sectional survey. A diarrheal episode was reported to have occurred in the previous 2 weeks among 298 (31.1%) children. Overall, 280 (80.3%) children sought care. Oral rehydration solution and zinc were used by 40.8% and 2%, respectively; 11% were admitted or received intravenous rehydration, and 29% sought care at health centers identified as sentinel centers for recruiting cases of diarrhea for a planned multicenter diarrheal etiology case-control study. Odds ratios for independent predictors of care-seeking behavior were lethargy, 4.14 (95% confidence interval = 1.45–11.77); fever, 2.67 (1.27–5.59); and stool frequency more than six per day, 2.29 (1.03–5.09). Perception of high cost of care and use of home antibiotics were associated with reduced care seeking: odds ratio = 0.28 (0.1–0.78) and 0.29 (0.11–0.82), respectively. There is a need for standardized, affordable, and accessible treatment of diarrhea as well as community education regarding appropriate care in areas with high diarrheal burden.

Introduction

Diarrheal illnesses were responsible for 15% of the estimated 8.8 million deaths worldwide among children under 5 years of age in 2008. Pakistan, with 465,000 estimated annual child deaths in 2008, has the fourth highest burden of child mortality in the world, contributing 5% or 1 in every 20 child deaths to the global child mortality pie.1 The continued high toll of diarrheal illnesses on Pakistani children's lives has a substantive impact on child survival through both the acute direct effect and chronic indirect impact on nutritional status.2 Death from diarrhea is preventable, provided that timely and appropriate care is provided. Part of this pathway is the parental/caregiver recognition of the need for help and the ability to seek care.

Pakistan was selected to be one of seven participating countries in the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) because of its high burden of child mortality and diarrhea-specific mortality and the availability of study sites in Karachi with demographic surveillance and necessary infrastructure and expertise to conduct sophisticated laboratory analyses at the Aga Khan University. GEMS aims to estimate the population-based burden, microbiologic etiology, and adverse clinical consequences of moderate-to-severe diarrhea among children 0–59 months of age in study sites in sub-Sahara Africa and South Asia to guide the development and implementation of vaccines and other interventions against diarrheal diseases.3

This paper describes background information on the study area and population, burden of diarrhea among children living in these communities, knowledge of caretakers regarding signs, symptoms, and preventive measures for diarrheal illnesses, patterns of healthcare use with trends over time, and factors associated with care-seeking behavior.

Material and Methods

Study setting.

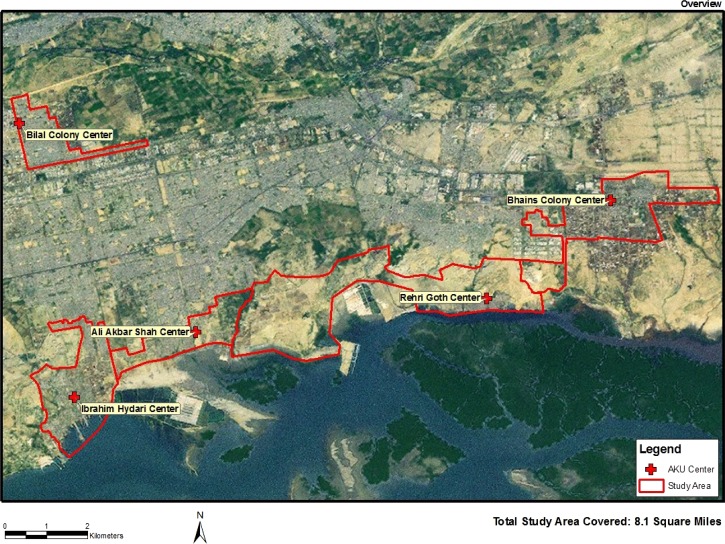

This study was conducted in three contiguous low-income communities approximately 20 km outside Karachi, where the Aga Khan University's Department of Pediatrics and Child Health has maintained demographic surveillance since 2003. These communities are coastal settlements, with a total area of 8.1 mi2 under surveillance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research sites, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Karachi.

Originally fishing villages, with the rapid expansion of Karachi, these areas have acquired a periurban character, with multiple ethnic groups and mixed livelihoods, including fishing, cattle farming for diary production, and small retail businesses serving the local population. The majority of the population resides in small, one- to two-room houses made with bricks or bamboo without improved sanitation facilities or running water. The residents of some areas have established piped water distribution networks by tapping the main municipal water supply. Where this network is not possible, residents have constructed community tanks or purchase water from vendors. Community living is very common, with multiple families residing in the same compound for generations. The climate is subtropical, with monsoon rains in the summer months of June to September.

The total population residing in the demographic surveillance area at the time of the Healthcare Utilization Survey (HUAS) was 78,858, with 11,894 children under the age of 5 years. Baseline population demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The surveillance area was extended in 2008 to include a fourth site adjacent to the existing study area to allow for a larger population from which diarrheal cases could be recruited for the GEMS case-control study.

Table 1.

Population demographics

| Demographic | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Total population | 74,858 |

| Number of under 5-year-old children | 11,894 (15.8%) |

| 0–11 months | 2,048 (17.2%) |

| 12–23 months | 2,425 (20.4%) |

| 24–59 months | 7,421 (62.4%) |

| Under 5 years mortality per 1,000 live births | 55 |

| HIV seroprevalence among women 15–49 years (%) | < 0.1 |

| Malaria endemicity19 | Low |

| Vitamin A supplementation coverage rate 6–59 m (%)20 | 65.8 |

| Coverage of DPT320 | 51.6% (5.7% card verified) |

| Mean size of household | 6.8 |

| Access to improved drinking water (%)10 | 61 |

| Access to improved sanitation facilities (%)10 | 49 |

| Number and nature of seasons21 | |

| Winter | Mid-December to February |

| Summer | Mid-April to October |

| Rainy season (monsoon) | July to initial September |

| Transitional (spring/autumn) | March to mid-April/November to mid-December |

| Health centers with these features in the demographic surveillance area | |

| Outpatient services only | ∼100 |

| GEMS sentinel sites (outpatient with intravenous hydration capability) | 6 |

| Overnight admission facilities | None |

Information from local surveillance data unless specified otherwise. The under 5 years population under surveillance was later expanded to 27,779 during the study period. DPT3 = diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

Local health facilities.

Each surveillance site has a primary healthcare clinic run by staff from the Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University. These clinics also function as study sites for various research projects. They provide free primary healthcare services between 9 AM and 4 PM daily for all children under 5 years of age residing in the demographic surveillance area and were designated sentinel health centers (SHCs) for the purpose of GEMS. Children requiring more specialized care are given free transport to a major public sector children's hospital in Karachi. In addition to these centers, there is one public sector 30-bed hospital and a local charitable clinic in close proximity to one of the centers that also agreed to participate as SHCs. None of the SHCs, including the government hospital or any other local area health facility, are staffed at night; therefore, there are no area health facilities for overnight admissions. Numerous pharmacies, licensed and unlicensed physicians, and traditional healers also operate in these communities.

Case definition and sample size.

A sample size of 1,140 was chosen for the primary end point of the survey (i.e., the proportion of children 0–59 months of age with the onset of moderate-to-severe diarrhea during the previous week who received care at an SHC associated with the site within 7 days of the onset of the illness). The sample size was independently powered for the three age strata, with 400 eligible children from the 0–11 months age group and 370 eligible children from each of the two older age strata (12–23 and 24–59 months), because there could be differences in disease incidence and care-seeking patterns between younger and older children. Moderate-to-severe diarrhea was defined as follows: child having three or more abnormally loose stools in 24 hours preceding presentation and (1) having moderate-to-severe dehydration (defined as the presence of one of the following: sunken eyes more than normal, decreased skin turgor, or history of receipt of intravenous rehydration), (2) having dysentery (diarrhea with visible blood in stool), or (3) being hospitalized with diarrhea or dysentery. Additional details on sample size derivation can be found in the paper by Nasrin and others.4

Selection of participants for the HUAS.

An updated census list was used to generate, using random selection, computerized lists of children in each age stratum. The baseline HUAS was conducted between July 1 and August 31, 2007, during the monsoon season. Caretakers/mothers living at home were the primary respondents. The Aga Khan University staff, trained in data collection, conducted the interviews.

After the GEMS moderate-to-severe diarrhea case-control study started, healthcare use patterns in the demographic surveillance area were reassessed over time, with the primary purpose of including potential temporal and seasonal trends in the primary end point. For this result, an abbreviated version of the HUAS (the HUAS-lite) was performed every 3 months. The sampling technique for HUAS-lite was the same as for the main HUAS. We report here results from the baseline HUAS and the trends from the first five rounds of HUAS-lite conducted from April of 2009 to March of 2011. The total under 5 years population at the beginning of the fifth round was 27,779 (Table 1).

Questionnaires.

HUAS.

The HUAS methods were adapted from generic protocols for hospital-based surveillance for rotavirus gastroenteritis and community-based survey on use of healthcare services for gastroenteritis in children under 5 years of age developed by the World Health Organization (WHO); one important difference is that our catchment population had ongoing demographic surveillance.5

The questionnaire consisted of ∼60 questions. Information about the household and family composition, occurrence and nature of recent diarrheal illnesses among children younger than 5 years, perceptions about the danger of diarrheal diseases in children, and attitudes and healthcare use practices was collected. To minimize recall bias, the primary caretakers of children who had suffered an episode of diarrhea within the past 14 days were queried about their attitudes concerning diarrhea, its prevention, and treatment. If the child did not experience diarrhea during the previous 14 days, then caretakers were asked hypothetical questions about their anticipated healthcare use should their child develop such an illness.

HUAS-lite.

The HUAS-lite questionnaire consisted of 21 questions and was administered only for children whose caretaker reported an episode of diarrhea during the preceding 14 days. Questions were limited to the clinical features of the illness, treatment at home, and healthcare use patterns.

Statistical analysis.

A weight was assigned to each responder (i.e., to each child in the sample for whom survey information was obtained). If the survey was only partially complete for a child, that child was considered a responder for the information obtained and a non-responder for the missing information. The weight assigned to each child represents the number of children in the population represented by the child. Weights were calculated by age and sex group. Thus, the weight for each responder is the population total in that category divided by the number of HUAS responders in the category. If information for a child in the HUAS sample could not be obtained after three attempts by the interviewer but the child was considered eligible according to age and location of residence, that child was kept in the sample and considered a non-responder. If the child was eligible but the primary caretaker refused to participate, the child was kept in the sample and considered a refusal.

We estimated the 2-week prevalence of any diarrhea, moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD), proportion of diarrhea cases seeking care outside the home, and proportion of MSD cases seeking care at one of the designated GEMS case-control study sentinel health facilities. Associations of variables with the probability of seeking care at a study healthcare facility and the probability of responding to the HUAS were assessed using logistic regression models, in which care-seeking behavior was the dependent variable. A multivariate model with stepwise selection was used that included all the variables significant at the univariate level (P ≤ 0.05).

Ethical approvals.

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Aga Khan University and the Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD. The interviewers were fluent in all of the languages spoken at the study sites, and they were required to read aloud the entire consent in the local language and provide the parent/primary caretaker with an opportunity to ask questions. Written informed consents were collected from all participants. The parent or primary caretaker received a copy of the signed consent form to keep, and the original was stored in the regulatory files at the study site. No breaches of confidentiality occurred.

Results

In the baseline HUAS, 1,086 households with children 0–59 months of age were approached, of which 959 (90.8%) households consented to participate. The children enrolled included 332 children ages 0–11 months, 302 children ages 12–23 months, and 325 children ages 24–59 months. The proportion of males and females in each group included in the survey was approximately equal.

Mothers (96.3%) with no formal education (84.9%) were the primary respondents. Respondents reported clean water and food (39.3%), improved nutrition (22.9%), and hand washing (22.7%) as the best ways to prevent diarrhea. Prevention through proper disposal of human waste (6.7%), vaccination (2.8%), and breast feeding (2.2%) were uncommonly or rarely reported. The most common signs indicating dehydration according to respondents' knowledge were lethargy (59.8%) followed by sunken eyes (24.4%), which were approximately equally distributed in all the age groups. Decreased urination (2.1%) and loss of consciousness (1.2%) were the least recognized signs of dehydration (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic profile and knowledge regarding diarrheal illness of the respondent population

| Total (N = 959) | 0–11 months (N = 332) | 12–23 months (N = 302) | 24–59 months (N = 325) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of rooms in the house | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.4 |

| Total under 5-year-old children | 2.2 ± 1.4 | 2.2 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.3 |

| Wealth index | −0.04 ± 0.98 | 0.10 ± 1.05 | −0.03 ± 0.92 | −0.09 ± 0.98 |

| Male child (%) | 50.0 | 49.0 | 50.0 | 50.2 |

| No formal education (%) | 84.9 | 77.2 | 84.1 | 87.5 |

| Relationship of the respondent with the child (mother; %) | 96.3 | 94.8 | 97.8 | 96.2 |

| Do you know ways to prevent these kinds of diarrhea? (%) | ||||

| Simple loose watery diarrhea | 51.7 | 51.0 | 50.0 | 52.6 |

| Rice watery diarrhea | 45.2 | 44.9 | 43.5 | 45.9 |

| Bloody diarrhea | 40.5 | 38.0 | 39.1 | 41.7 |

| Best way to prevent diarrhea* (%) | ||||

| Clean water and food | 39.3 | 37.0 | 35.9 | 41.3 |

| Improved nutrition | 22.9 | 17.4 | 20.5 | 25.4 |

| Hand washing | 22.7 | 22.8 | 22.1 | 22.9 |

| Medications | 7.9 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 8.4 |

| Proper disposal of human waste | 6.7 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 6.0 |

| Vaccines | 2.8 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 3.0 |

| Breastfeeding | 2.2 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 1.7 |

| Signs considered by respondents as indicators of dehydration (%) | ||||

| Lethargy | 59.8 | 60.6 | 63.2 | 58.4 |

| Sunken eyes | 24.4 | 23.5 | 24.8 | 24.6 |

| Increased thirst | 14.5 | 16.6 | 15.2 | 13.6 |

| Dry mouth | 11.9 | 15.5 | 13.9 | 10.0 |

| Wrinkled skin | 6.7 | 7.7 | 7.3 | 6.2 |

| Decreased urination | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| Coma/loss of consciousness | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

Multiple responses.

The 2-week prevalence of diarrhea was found to be 31.1% overall and 43.2%, 37.6%, and 25.1% among children in the 0–11, 12–23, and 24–59 months age strata, respectively. Care was sought outside the home for 80.3% of the reported diarrheal episodes. Fever was reported in 74.9% of episodes and more commonly seen in the 0–11 age group (81.3%), whereas vomiting (31.6%), blood in stools (9.1%), and passage of more than six stools per day (23.2%) occurred with lower frequency. Intravenous rehydration and/or hospitalization was reported by 11% of the respondents (Table 3).

Table 3.

Diarrheal prevalence, clinical symptoms, and health-seeking behavior of respondents with diarrheal children

| Total (N = 959) | 0–11 months (N = 332) | 12–23 months (N = 302) | 24–59 months (N = 325) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of diarrhea | ||||

| Had diarrhea in the last 2 weeks (%) | 31.1 | 43.2 | 37.6 | 25.1 |

| MSD (%) | 27.1 | 33.4 | 33.5 | 22.8 |

| Severity of diarrhea* | N = 349 | N = 150 | N = 113 | N = 86 |

| Dysentery (%) | 9.1 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 10.9 |

| Required hospitalization (%) | 11.0 | 15.1 | 11.6 | 8.5 |

| Required intravenous rehydration (%) | 11.2 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 8.7 |

| Sunken eyes | 79.3 | 70.5 | 80.1 | 83.4 |

| Wrinkled skin | 61.8 | 58.8 | 61.0 | 63.6 |

| Sought care | ||||

| Yes (%) | 80.3 | 83.2 | 77.4 | 80.3 |

| No (%) | 19.7 | 16.8 | 22.6 | 19.7 |

| Difficulties in seeking care | ||||

| Lack of transportation (%) | 13.3 | 14.7 | 8.8 | 15.1 |

| Lack of childcare for other children (%) | 9.4 | 10.6 | 7.0 | 10.2 |

| Heavy rain or flooding (%) | 9.2 | 5.9 | 12.3 | 9.1 |

| Cost of treatment too high (%) | 7.6 | 11.3 | 6.9 | 6.1 |

| Never a problem (%) | 54.1 | 52.7 | 55.7 | 53.9 |

| Clinical symptoms of children with diarrhea | ||||

| Increase thirst (%) | 91.3 | 88.0 | 91.4 | 92.9 |

| Lethargy (%) | 89.9 | 88.5 | 93.0 | 89.0 |

| Dry mouth (%) | 83.0 | 84.2 | 78.5 | 84.8 |

| Sunken eyes (%) | 79.3 | 70.5 | 80.1 | 83.4 |

| Fever (%) | 74.9 | 81.3 | 70.9 | 73.8 |

| Wrinkled skin (%) | 61.8 | 58.8 | 61.0 | 63.6 |

| Rice watery stools (%) | 47.9 | 49.6 | 47.2 | 47.4 |

| Mucus/pus in stools (%) | 46.3 | 45.6 | 47.0 | 46.3 |

| Decreased urination (%) | 32.2 | 28.8 | 33.5 | 33.3 |

| Vomiting (%) | 31.6 | 43.7 | 28.2 | 27.2 |

| Blood in stools (%) | 9.1 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 10.9 |

| Coma/loss of consciousness (%) | 8.3 | 7.4 | 11.2 | 7.2 |

| More than six stools per day | 23.2 | 27.5 | 21.9 | 21.6 |

| Duration of diarrhea (days) | 7.5 ± 11.1 | 9.8 ± 15.2 | 7.0 ± 10.1 | 6.5 ± 8.7 |

| Treatment given at home before seeking care* | ||||

| Offered to eat (%) | 55.9 | 55.1 | 64.4 | 51.6 |

| Offered to drink (%) | 77.5 | 76.6 | 78.7 | 77.3 |

| ORS (%) | 32.5 | 36.5 | 36.6 | 28.2 |

| Homemade fluid (%) | 27.5 | 23.4 | 31.5 | 27.4 |

| Antibiotics (%) | 7.7 | 7.3 | 12.6 | 5.2 |

| Herbal medication (%) | 3.7 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| Milk or formula (%) | 2.4 | 5.5 | 3.2 | 0.4 |

| No home remedies given (%) | 39.3 | 35.7 | 28.6 | 47.0 |

| Healthcare choices for those caretakers who sought care | N = 284 | N = 132 | N = 89 | N = 63 |

| Licensed doctor outside SHC (%) | 56.2 | 56.8 | 62.1 | 52.7 |

| SHC (%) | 29.4 | 24.2 | 28.4 | 32.6 |

| Unlicensed (%) | 13.3 | 17.4 | 9.5 | 13.1 |

| Pharmacy (%) | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| Treatment prescribed by healthcare providers* | ||||

| ORS (%) | 40.8 | 36.8 | 40.9 | 42.9 |

| Medicine by injection (%) | 31.1 | 28.8 | 36.9 | 29.3 |

| Antibiotics (%) | 18.8 | 25.4 | 15.5 | 17.0 |

| Zinc (%) | 2.0 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 0.0 |

| Do not know (%) | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 2.0 |

Multiple responses.

The most frequently described reason for not seeking care among caretaker of children with diarrhea was lack of transport (13.3%) followed by no childcare for other children (9.4%), heavy rains or flooding (9.2%), and high cost of therapy (7.6%). No home treatment was given by 39.3% of the caretakers before seeking care. Oral rehydration salts and homemade fluids were used by only 32.5% and 27.5% of the respondents, respectively (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Results from multivariate regression analyses with demographic, socioeconomic, home care practices, and clinical indicators as predictors of healthcare seeking among caretakers of children with diarrhea

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of lethargy as a sign of dehydration | 0.39 (0.18–0.85) | 0.02 |

| Presence of more than six stools per day | 2.29 (1.03–5.09) | 0.04 |

| Presence of fever | 2.67 (1.27–5.59) | 0.01 |

| Presence of lethargy | 4.14 (1.45–11.77) | 0.01 |

| Antibiotics given at home | 0.29 (0.11–0.82) | 0.02 |

| Difficult to seek care, because cost of treatment is too high | 0.28 (0.1–0.78) | 0.01 |

The first choice of healthcare provider among those caretakers who sought care was a local licensed doctor (56.2%) followed by SHCs (29.4%). Oral rehydration salts were prescribed by only 40.8% of healthcare providers; 31.1% reported injectable medicine use. Zinc was prescribed for only 2% of the children who sought care.

The sociodemographic profile, parent/caretaker's knowledge of diarrhea prevention, child's sex, and signs of dehydration were not significantly different among the children with diarrhea who were taken for healthcare compared with those children with diarrhea who were not taken for healthcare in a univariate analysis (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Using a stepwise multivariate regression analysis, the characteristics of parents/caretakers associated with decreased care-seeking behavior included knowledge that lethargy is a sign of dehydration (P = 0.02), concern that the high cost of treatment impedes care-seeking behavior (P = 0.01), and provision of antibiotics at home (P = 0.02). However, parents/caretakers who perceived that their child had lethargy (P = 0.01), fever (P = 0.01), or frequent (more than six per day) loose stools were significantly more likely to seek care outside the home.

There was little variation noted in the prevalence of diarrhea and care-seeking behavior over the duration of the study in the HUAS-lite surveys, although the proportion reporting diarrhea in the previous 2 weeks was much lower than in the baseline survey (Supplemental Table 3). For MSD, the overall proportion of children seeking care at the SHC during the five HUAS-lite surveys was 23.5%, 20.5%, and 24.4% in the youngest, middle, and oldest strata, respectively. The mean proportion with MSD seeking care at SHCs for all strata and HUAS-lite surveys combined was 22.6%.

Discussion

When a child falls ill, the knowledge of his/her caretaker regarding the natural history of the disease and the caretaker's ability to seek appropriate care for the child play a vital role in reducing the morbidity and mortality from that illness. The association between not seeking care, delay in seeking care, and infant deaths is well-established. Poverty, sex, mother's recognition of the severity of child's illness, parental education, distance from the health facility, user fees, and health system responsiveness have all been shown to predict mortality.6–8

Our results are comparable with the results reported in the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey9 (PDHS 2006–2007) and the Pakistan Living Standard Measurement Survey (PLSMS 2010–2011),10 indicating that our study sites are broadly representative of Pakistan as far as diarrheal disease burden is concerned. We found the 2-week prevalence of diarrhea to be 31% compared with 22% reported in PDHS. During the five HUAS-lite surveys, the 2-week prevalence of diarrhea among all three age strata combined ranged from 10.1% to 15.2%. Using the need for hospitalization and/or intravenous fluids, sunken eyes, wrinkled skin, and/or dysentery as a gauge of severity of diarrheal illness, 27% of children surveyed in the baseline HUAS reported an episode of MSD; however, in the serial HUAS-lite surveys, MSD prevalence varied between 1.9% and 5.5%. Possible explanations for these differences include the conduct of the baseline HUAS during a short period in the high monsoon season when diarrheal incidence peaks in Pakistan and cholera outbreaks tend to occur. This explanation may explain the reported 11% hospitalization and/or intravenous hydration rate in the baseline HUAS. Another possible explanation is that the ability of fieldworkers to ascertain responses to the questions related to diarrheal severity improved with time. Of note, the frequency with which caretakers reported the presence of sunken eyes in the baseline HUAS was much higher than the frequency reported in the HUAS-lite. Although diarrheal prevalence was high in all age groups, there was a decline with increasing age that was observed in the baseline as well as HUAS-lite surveys. Dysentery was more common in the older age group. These age trends are consistent with the trends reported for diarrhea from other parts of Asia11,12 and for dysentery in the work by Kotloff and others.13

Levels of knowledge among mothers in areas of fundamental importance for diarrheal disease prevention, such as importance of exclusive breastfeeding and proper disposal of feces, were strikingly low. Exclusive breastfeeding is known to provide significant protection against diarrheal diseases and related mortality.14,15 The recent meta-analysis by Lamberti and others16 found a significant protective effect of breastfeeding against diarrhea mortality in developing countries during the first 2 years of life. However, only 2.2% of mothers in our survey were aware that breastfeeding is a good way to prevent diarrhea. The PDHS national survey reported exclusive breastfeeding rates in Pakistan for children less than 6 months of age to be only 37%.9 These findings provide key targets for diarrheal illness prevention interventions, because several studies have shown that breastfeeding rates and waste disposal techniques can be dramatically improved by community-oriented programs including education and peer counseling for women and training of licensed private providers.17,18

Care-seeking behavior was high in our surveys, and licensed private providers were preferred. Although free care was provided in our SHCs, the proportion of caretakers seeking care at the SHCs was 29.4% in the baseline survey, and it averaged 22.6% in the HUAS-lite surveys. Although the study did not explore the reasons for preferring particular providers, there are some providers in the area with deep community roots, with whom many families have a long-term relationship. The low rates of prescription of oral rehydration solutions (ORSs) and zinc by local providers, both mainstays of diarrhea therapy, are highlighted by this study and provide another avenue for educational interventions. We found that mothers who correctly perceived the signs of severity are more likely to seek care. Clinical symptoms indicating the severity of diarrhea, such as fever, dry mouth, sunken eyes, lethargy, vomiting, and wrinkled skin, were better perceived as important signs of dehydration by mothers who sought care in univariate analysis, although only fever, lethargy, and frequent stooling remained significant in the multivariate model.

The strength of our survey is that it was done in a randomly selected sample from a large periurban low-socioeconomic community setting with high community participation rates and repeated observations over time. Limitations of the baseline HUAS include the conduct of a single study during the high monsoon season, which may have overestimated the prevalence of overall diarrhea as well as MDS. Whereas caretakers reported that the majority of children with diarrhea had associated sunken eyes and wrinkled skin, they did not consider these signs to be signs of dehydration and were not more likely to seek healthcare when present. As a result, we cannot determine with certainty to what extent the caretakers reporting of these signs lacks specificity as a gauge of diarrheal severity or goes unrecognized as a trigger for seeking care.

A number of public health issues are raised by this study, and several gaps in the understanding of the community regarding diarrhea have been identified. Clearly, there is a need for community and healthcare provider education on prevention of diarrhea, including the promotion of breastfeeding and adequate disposal of waste, as well as appropriate case management should diarrhea occur. Community participatory approaches for diarrhea prevention and treatment offer the most viable strategies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to those individuals who conducted the HUAS and HUAS-lite surveys. The authors thank all who participated in this study and the physician and staff at the site for their hard work in conducting these surveys.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Grant 38874 (M.M.L., Principal Investigator).

Authors' addresses: Farheen Quadri, Asia Khan, Tabassum Bokhari, Shiyam Sunder Tikmani, Muhammed Imran Nisar, Zaid Bhatti, and Anita K. M. Zaidi, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan, E-mails: farheen.quadri@aku.edu, asia.khan@aku.edu, tabassumubbashar@hotmail.com, shiyam.sunder@aku.edu, imran.nisar@aku.edu, zaid.bhatti@aku.edu, and anita.zaidi@aku.edu. Dilruba Nasrin, Karen Kotloff, and Myron M. Levine, Center for Vaccine Development, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, E-mails: dnasrin@medicine.umaryland.edu, kkotloff@medicine.umaryland.edu, and mlevine@medicine.umaryland.edu.

References

- 1.Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, De Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C, Rivera J. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371:243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotloff KL, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Nataro JP, Farag TH, van Eijk A, Adegbola RA, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Golam Faruque AS, Saha D, Sow SO, Sur D, Zaidi AK, Biswas K, Panchalingam S, Clemens JD, Cohen D, Glass RI, Mintz ED, Sommerfelt H, Levine MM. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55((Suppl 4)):S232–S245. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasrin D, Wu Y, Blackwelder WC, Farag TH, Saha D, Sow SO, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Sur D, Faruque ASG, Zaidi AKM, Biswas K, Van Eijk AM, Walker DG, Levine MM, Kotloff KL. Health care seeking for childhood diarrhea in developing countries: evidence from seven sites in Africa and Asia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89((Suppl 1)):3–12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . Generic Protocols for (i) Hospital-Based Surveillance to Estimate the Burden of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis in Children and (ii) a Community-Based Survey on Utilization of Health Care Services for Gastroenteritis in Children, Field Test Version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owais A, Sultana S, Stein AD, Bashir NH, Awaldad R, Zaidi AK. Why do families of sick newborns accept hospital care? A community-based cohort study in Karachi, Pakistan. J Perinatol. 2011;31:586–592. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaikh BT, Hatcher J. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2005;27:49. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, de Bernis L. Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save? Lancet. 2005;365:977–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute of Population Studies I, Pakistan . Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2006. Columbia, MA: IRD/Macro International; 2007. p. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of Pakistan SD, Federal Bureau of Statistics . Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey (Pslm) 2010–11. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Gilany AH, Hammad S. Epidemiology of diarrhoeal diseases among children under age 5 years in Dakahlia, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11:762–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotloff KL, Winickoff JP, Ivanoff B, Clemens JD, Swerdlow DL, Sansonetti PJ, Adak GK, Levine MM. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:651–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui A, Caulfield L, Becker S. Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics. 2001;108:e67. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.4.e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quigley MA, Kelly YJ, Sacker A. Breastfeeding and hospitalization for diarrheal and respiratory infection in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort Study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e837. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamberti LM, Fisher Walker CL, Noiman A, Victora C, Black RE. Breastfeeding and the risk for diarrhea morbidity and mortality. BMC Public Health. 2011;11((Suppl 3)):S15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:42–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aamer I, Yawar YM, Zulfiqar B. Effect of breastfeeding promotion interventions on breastfeeding rates, with special focus on developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11((Suppl 3)):S24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO World Malaria Report. 2011. http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2011/9789241564403_eng.pdf Available at. Accessed July 1, 2012.

- 20.National Nutritional Survey of Pakistan Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Aga Khan University. 2011. http://pakresponse.info/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=BY8AFPcHZQo%3D&tabid Available at. Accessed July 5, 2012.

- 21.Pakistan Meteorological Department . Islamabad: Government of Pakistan; http://www.pmd.gov.pk/ Available at. Accessed July 1, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.