Abstract

Background:

Overweight and obesity is becoming an increasingly prevalent problem in both developed and developing world, and is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century. Although various studies demonstrated pediatric obesity-related factors, but, due to its ongoing hazardous effects, researchers aimed to assess obesity-related factors in school-aged children in Rasht, Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This was a case–control study which was performed in eight primary schools of Rasht. A cluster sampling method was used to select 320 students including 80 in case (BMI ≥85th percentile for age and gender) and 240 in control group (BMI = 5th-85th percentile for age and gender). Data were collected by a scale, a tape meter, and a form which consisted of obesity-related factors, and were analyzed by Chi-square, Mann–Whitney, and stepwise multivariate regression tests in SPSS 19.

Results:

Findings showed that the mean and standard deviation of birth weight (g) in case and control groups were 3671 ± 5.64 and 190 ± 5.46, respectively (P = 0.000). 82.5% of case and 92.9% of control group had exclusive breastfeeding for 4-6 months (P = 0.024). Also, multivariate regression analysis indicated that birth weight, age, exclusive breastfeeding, and frequency of meals have significant effects on body mass index (BMI).

Conclusions:

It seems that more accurate interventions for primordial prevention are essential to reduce childhood obesity risk factors, including promotion of pre-pregnancy and prenatal care to have neonates who are appropriate for gestational age and also improving exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life. In addition, identifying children at risk for adolescent obesity provides physicians and midwives with an opportunity for earlier intervention with the goal of limiting the progression of abnormal weight gain.

Keywords: Body mass index, obesity, school age

INTRODUCTION

The issue of being overweight and obese is becoming an increasingly prevalent problem in both developed and developing world, and it is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century.[1] During the past two decades, the prevalence of obesity in children has risen greatly worldwide and elementary school-aged children (6-11 years) have the highest prevalence of overweight (18.8%).[2,3]

Obesity in childhood and adolescence has adverse consequences on premature mortality and physical morbidity in adulthood and is associated with impaired health during childhood.[4] Based on the available evidence, childhood obesity closely associates with cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, asthma, type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus, increased insulin level, and orthopedic problems.[5]

There are controversial results regarding obesity risk factors in which different studies revealed genetic history, physical activity,[6,7,8,9] high birth weight,[10,11,12] type of milk consumed during infancy,[13] more than 2 h television watching per day,[14,15] number of regular meals, and parental overweight[16,17,18,19,20] as the risk factors of obesity. In addition, there are some studies which revealed no related factor to obesity in normal and obese groups.[21,22,23]

Although, various studies demonstrated pediatric obesity-related factors. but due to the hazardous and adverse effects of obesity on health, it seems that determining and assessing the risk factors of obesity in children is mandatory.

Aim

We aimed to assess obesity-related factors in school-aged children in Rasht, Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this case–control study, 320 primary school students of age 7-11 years [80 children as cases (obese) and 240 as controls (normal weight)] participated based on cluster sampling from eight schools of four zones (north, south, east, and west) in Rasht, which consisted of one girls’ and one boys’ elementary school per zone.

Data were collected by a scale, a tape meter, and a form which was designed based on the research objectives, and approved by Vice-Chancellor of research in Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS). Also, its validity was checked by 10 faculty members of GUMS.

Parents signed the written consent, and parents’ and students’ weight and height were measured. Measurements were taken with the subjects in light indoor clothing and when they were barefoot or with stockings. The subjects were weighed to the nearest 0.1 kg with an electronic scale (Girmi, Germany) that was calibrated daily at the beginning of each working day. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a tape meter in a vertical erect position, with parallel feet, and with the shoulders and bottom touching the wall. The height and weight data were used to calculate the body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) using the formula: Weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. Overweight and obese group was identified as BMI ≥85th percentile and normal group was indicated between 5th and 85th percentile for age and sex. They were matched according to age and sex.

The forms which included children's demographic characteristics (such as age, gender, educational level, child's rank in the family) and factors such as birth weight, meals frequency (per day), duration of TV watching (h), daily and nightly sleep duration (h), factors regarding breastfeeding and supplementary food and parental factors (age, educational level, middle income, and BMI) were completed through interview. Data were analyzed by Mann–Whitney, Chi-square, and stepwise multivariate regression tests using SPSS 19.

RESULTS

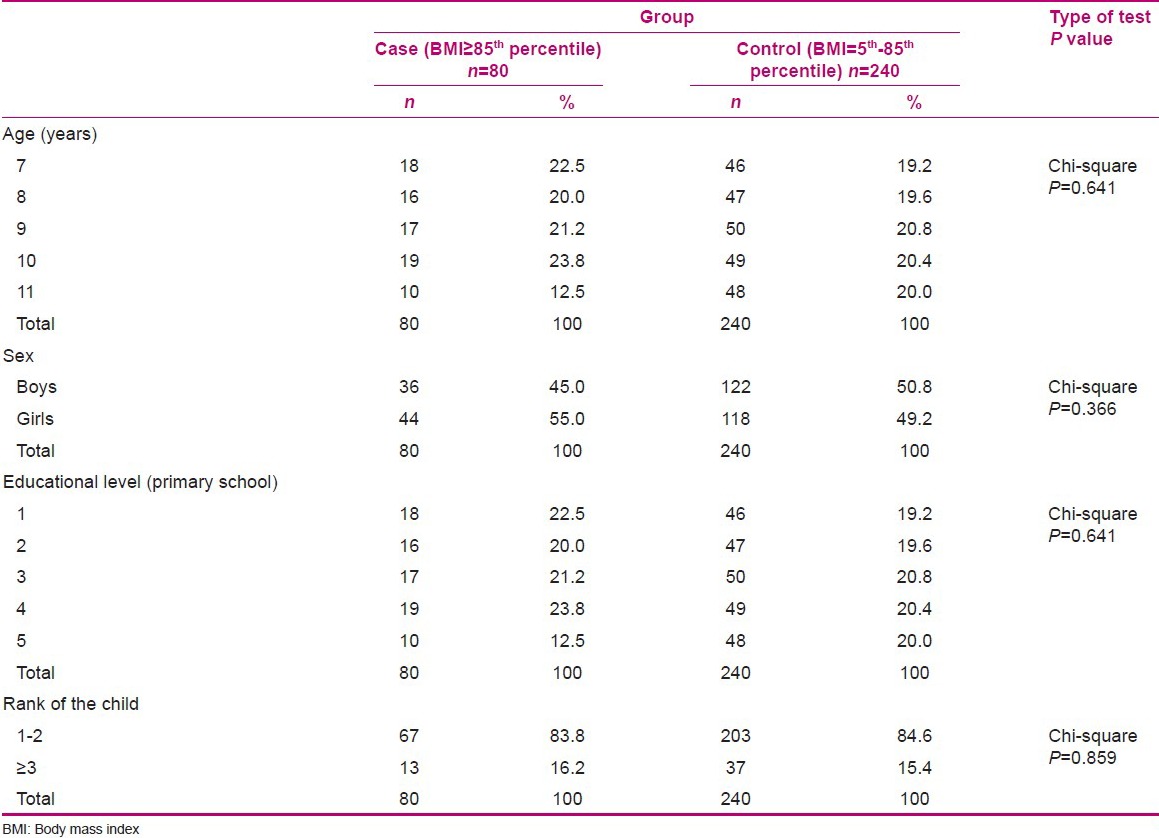

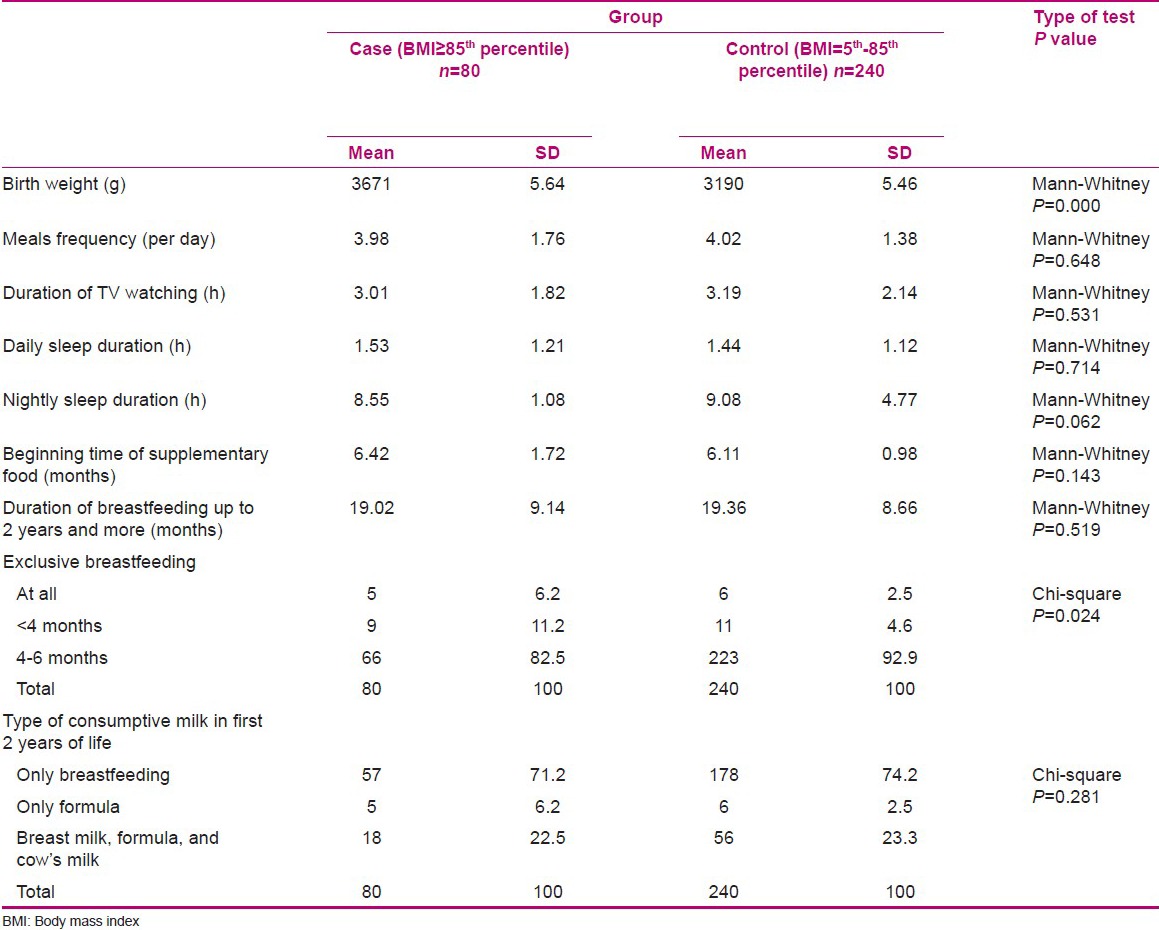

Results showed no significant difference between children's demographic characteristics in case and control groups [Table 1]. Mean and standard deviation of birth weight (g) in case and control groups were 3671 ± 5.64 and 3190 ± 5.46, respectively, which showed statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.000).

Table 1.

Distribution of children's demographic characteristics in case and control groups

82.5% of cases and 92.9% of controls had exclusive breastfeeding for 4-6 months (P = 0.024). In addition, the mean and standard deviation of breastfeeding duration in the case and control groups were 19.02 ± 9.14 and 19.36 ± 8.66, respectively (P > 0.05). Furthermore, results related to pediatric factors which demonstrated no significant relation are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relationship between children's BMI and some obesity risk factors

Although there was no significant relation between parental factors and obesity, the mean and standard deviation of mother's BMI in cases were 28.04 ± 4.02 and in the control group were 26.71 ± 4.19, which demonstrated statistically significant difference (P = 0.013). and The mean and standard deviation of father's BMI were 26.57 ± 3.63 and 25.43 ± 3.65 in case and control groups, respectively, and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.016).

Stepwise multivariate regression analysis indicated that birth weight (P < 0.04), weight (P = 0.000), age (P = 0.000), and meals frequency (P < 0.01) had significant effects on BMI in children. On the other hand, these variables produced 0.80 variance in BMI.

DISCUSSION

It was found in this study that the mean and standard deviation of birth weight in obese children were significantly higher than in the control group, which is in agreement with the study results of Armstrong et al. and Rezaii et al.[13,16] However, some studies demonstrated no significant relation between birth weight and obesity.[24,25,26,27,28]

According to our results, there is an inverse association between meal frequency and BMI. Also, Turkish researchers recently observed that the proportion of obese students that consumed fewer than three meals was significantly higher than those who consumed regular meals during the day (χ2 = 16.2; P < 0.01).[29] This may suggest that fewer and irregular meals’ consumption can be associated with eating junk foods and excess of pediatric weight gain.

Although in this study the mean and standard deviation of TV watching duration showed no statistically significant difference between groups, Kauer et al. clearly indicated that reduction in TV watching among 7–11-year-old girls may help to reduce their risk of weight gain during late childhood.[30]

In addition, there was no significant relation between daily sleep duration and obesity, but the mean and standard deviation of nightly sleep duration in the control group were more than in the overweight/obese group and the difference between groups was nearly significant. In other words, children who had longer nightly sleep may be less obese. However, Rezai and colleagues showed that there was significant difference in the duration of daily and nightly sleep between obese and normal children.[16]

In the present study, the average and standard deviation of breastfeeding duration (up to 2 years and more) in cases was less than in the normal group, but this difference was not statistically significant. On the other hand, the findings showed that most children with normal weight compared with overweight and obese group had exclusive breastfeeding for 4-6 months and this difference was statistically significant. Shahadeh and colleagues found that breastfeeding duration in obese group was significantly less than in normal weight group.[31] Also, Kelishadi et al. showed the frequency of breastfeeding without other types of milk and duration of breastfeeding in obese children was lower than in the control group[21] and Kalies et al. also suggested that exclusive breastfeeding can prevent weight gain.[32]

It is seen from the results that there was no significant relation between parents’ age, educational level, and middle income with childhood obesity. Although in another study, researchers demonstrated no significant relation between mother's education in both groups, they found significant difference between obesity and economic status (P < 0.003).[16] Also, Italian Institute of Health observed an inverse relationship between the parents’ educational level and childhood obesity. They revealed that the lowest educational level corresponded to the highest prevalence of obese children.[33]

In this study it was found that mothers and fathers of students with BMI ≥85th percentile had higher BMI. Lazzeri and colleagues observed that the prevalence of obese children increases with increasing parents’ BMI classes (P = 0.01). Furthermore, the prevalence of obese children with obese mothers is higher than children with obese fathers, but the difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.3).[33] Also, Rezai and colleagues reported that there was significant difference in mothers’ BMI between normal and obese children (P = 0.001).[16] It seems that parents’ obesity, particularly mothers’ obesity, and incorrect food habits in the family can be an important factor in increasing of the children's weight.

The results of this study show that obtaining obesity risk factors and identifying children at risk for adolescent obesity provide health workers with an opportunity for earlier intervention with the goal of limiting the progression of abnormal weight gain. Moreover, primordial prevention is essential to reduce childhood obesity risk factors, including promotion of pre-pregnancy and prenatal care to have neonates who are appropriate for gestational age and also improving exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life. In addition, parents can play a significant role in implementing school-based obesity preventive programs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank all the participants in our research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil

REFERENCES

- 1.Cretikos MA, Valenti L, Britt HC, Baur LA. General practice management of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents in Australia. Med Care. 2008;46:1163–9. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318179259a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelian Sh, modarres M, Faghihzadeh S, Safdari Ml. The relationship between lactation pattern in infant period and obesity in 5-6 year old children. Hayat. 2004;20:63–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huffman FG, Kanikireddy S, Patel M. Parenthood-A contributing factor to childhood obesity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010 doi: 10.3390/ijerph7072800. 7280010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reilly JJ, Kelly J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int J Obes. 2011;35:891–8. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang J, Rosenqvist U, Wang H, Greiner T, Ma Y, Toschke AM. Risk factors for overweight in 2- to 6-year-old children in Beijing, China. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1:103–8. doi: 10.1080/17477160600699391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyce T. The media and obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8(Suppl 1):201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekelund U, Aman J, Yngve A, Renman C, Westerterp K, Sjostrom M. Physical activity but not energy expenditure is reduced in obese adolescents: A case control study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:935–41. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krebs NF, Himes JH, Jacobson D, Nicklas TA, Guilday P, Styne D. Assessment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):193–228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhai F, He Y, Wang Z, Yu W, Hu Y, Yang X. The status and trends of dietary nutrients intake of Chinese population. [Ying Yang xue Bao] Acta Nutrimenta Sinica. 2005;27:181–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hui LL, Nelson EA, Yu LM, Li AM, Fok TF. Risk factors for childhood overweight in 6- to 7-y-old Hong Kong children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1411–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma A, Sharma K, Mathur KP. Growth pattern and prevalence of obesity in affluent schoolchildren of Delhi. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:485–91. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007223894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Liu E, Tian Z, Wang W, Ye T, Liu G, et al. High birth weight and overweight or obesity among Chinese children 3-6 years old. Prev Med. 2009;49:172–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armstrong J, Reilly JJ. Child health information team. Breastfeeding and lowering the risk of childhood obesity. Lancet. 2002;359:2003–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, King MA, Pickett W. Overweight and obesity in Canadian adolescents and their associations with dietary habits and physical activity patterns. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Boyce WF, Vereecken C, Mulvihill C, Roberts C, et al. Health behaviour in school-aged children obesity working group. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obes Rev. 2005;6:123–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezaii M. The relationship between lactation patterns and preschool children weight in Sari. J Nurs Midwifery Fac Guilan Med Univ. 2005;53:52–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson J, Forsén T, Tuomilehto J, Osmond C, Barker D. Size at birth, childhood growth and obesity in adult life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:735–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dennison BA, Erb TA, Jenkins PL. Television viewing and television in bedroom associated with overweight risk among low-income preschool children. Paediatrics. 2002;109:1028–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkkahraman D, Bircan I, Tosun O, Saka O. Prevalence and risk factors of obesity in school children in Antalya, Turkey. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:1028–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu ZB, Han SP, Zhu GZ, Zhu C, Wang XJ, Cao XG, et al. Birth weight and subsequent risk of obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2011;12:525–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelishadi R, Hashemipoor M, Famouri F, Sabet B, Sanei B. The impact of breastfeeding in prevention of obesity in children. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2005;35:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garipagaoglu M, Budak N, Süt N, Akdikmen Ö, Oner N, Bundak R. Obesity Risk Factors in Turkish Children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2009;24:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zawodnia K, Szalapska M, Stawerska R, Lewinski A. The prevalence of obesity of children (aged 13-15) and the significance of selected obesity risk factors. Arch Med Sci. 2007;3:376–82. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strufaldi MW, Silva EM, Puccini RF. Overweight and obesity in prepubertal schoolchildren: The association with low birth weight and family antecedents of cardiovascular disease. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:4465–72. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011001200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loos RJ, Beunen G, Fagard R, Derom C, Vlietinck R. Birth weight and body composition in young adult men-a prospective twin study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1537–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michels KB, Willett WC, Graubard BI, Vaidya RL, Cantwell MM, Sansbury LB, et al. A longitudinal study of infant feeding. and obesity throughout life course. Intl J Obes. 2007;31:1078–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalantari N, Shenavar R, Rashidkhani B, Hooshiar A, Nasihat Kon A, Abdollah Zadeh M. The relation between obesity and overweight with breastfeeding, birth weight and socioeconomic situation. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2010;3:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loos RJ, Beunen G, Fagard R, Derom C, Vlietinck R. Birth weight and body composition in young women: A prospective twin study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:676–82. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dündar C, Öz H. Obesity-related factors in Turkish school children. Sci World J. 2012;2012:353–485. doi: 10.1100/2012/353485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaur H, Choi WS, Mayo MS, Harris KJ. Duration of television watching is associated with increased body mass index. J Pediatr. 2003;143:506–11. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shehadeh N, Weitzer-Kish H, Shamir R, Shihab S, Weiss R. Impact of early postnatal weight gain and feeding patterns on body mass index in adolescence. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21:9–15. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2008.21.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalies H, Heinrich J, Borte N, Schaaf B, von Berg A, von Kries R, et al. The effect of breastfeeding on weight gain in infants. Eur J Med Res. 2005;10:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazzeri G, Pammolli A, Pilato V, Giacchi MV. Relationship between 8/9-yr-old school children BMI, parents’ BMI and educational level: A cross sectional survey. Nutr J. 2011;10:76. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]