Abstract

Background:

Empowerment of people with diabetes means integrating diabetes with identity. However, others’ stigmatization can influence it. Although diabetes is so prevalent among Iranians, there is little knowledge about diabetes-related stigma in Iran. The present study explored diabetes-related stigma in people living with type 1 diabetes in Isfahan.

Materials and Methods:

A conventional content analysis was used with in-depth interview with 26 people with and without diabetes from November 2011 to July 2012.

Results:

A person with type 1 diabetes was stigmatized as a miserable human (always sick and unable, death reminder, and intolerable burden), rejected marriage candidate (busy spouse, high-risk pregnant), and deprived of a normal life [prisoner of (to must), deprived of pleasure]. Although, young adults with diabetes undergo all aspects of the social diabetes-related stigma; in their opinion they were just deprived of a normal life

Conclusion:

It seems that in Isfahan, diabetes-related stigma is of great importance. In this way, conducting an appropriate intervention is necessary to improve the empowerment process in people with type 1 diabetes in order to reduce the stigma in the context.

Keywords: Diabetes, disease-related stigma, Iran, people with diabetes, qualitative research, social stigma

INTRODUCTION

Review of nursing and medicine studies indicates that empowerment process in people with diabetes mostly focuses on effective diabetes disease, self-efficacy, and health-related behaviors,[1,2,3,4] although recent findings proved that empowerment means integrating diabetes with identity. However, living with diabetes is a progressive dialog of the person with his/her self and the world,[5] which is associated with disrupting identity.[6] To this, it is necessary to focus on different aspects of having diabetes including self and identity.[7,8,9,10]

Identity, which is the outcome of social and interpersonal relations with others,[11] can be affected by the person's view about him/herself and others’ perspective about the person.[12] Unfortunately; some people affect others’ identity by stigmatization[13] as people tend to internalize the social stigma.[14] Consequently, stigmatized identity would be replaced with real identity in stigmatized people because of losing real identity during this process.[15,16] Stigma includes labeling, shaming, denying,[17] and rejecting because of social judgment about a person or a special group.[18] It has been linked to some chronic diseases such as mental disorders, cancer, tuberculosis, and diabetes for so many years,[18] specifically in Asian societies.[16] For example, type 1 diabetes is a social stigma in India; as a response, many parents try to hide their daughters’ diabetes from their teachers, friends, and relatives.[19] In addition, low chances or intention to marriage and having child among Indians and Japanese[19,20,21,22] are some negative effects of diabetes-related stigma on the well-being and quality of life of the people in Asian countries. To this, diabetes-related stigma could be an important factor, which has threatened the person's identity all over the world.[8,23,24] However, people need to reconstruct a new identity with no diabetes-related stigma, to be known as a “person with diabetes” not a “diabetic patient.”[5,25,26,27]

It seems there is a similar situation in Iran. According to various studies conducted in 2008 and 1992, it was revealed that Iranian parents mostly hide their children's diabetes from others to extricate them from labeling.[28,29] Diabetes-related stigma can be a strong obstacle in the empowerment process in living with diabetes due to the lack of specific information about it in case of Iran; this study aimed to identify diabetes-related stigma in people living with type 1 diabetes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The research was based on in-depth interviews with 26 participants in order to approach a conventional content analysis (8 people with diabetes, 5 family members, and 13 people with no diabetes and even no close relation with a person having diabetes). The participants were selected purposefully from November 2011 to July 2012 and sampling was continued till saturation. The people with diabetes and family members were recruited from Isfahan Endocrinology Research Center, while the people without diabetes were selected from public places in Isfahan such as mosques, bus stations, parks, etc., [Tables 1-3].

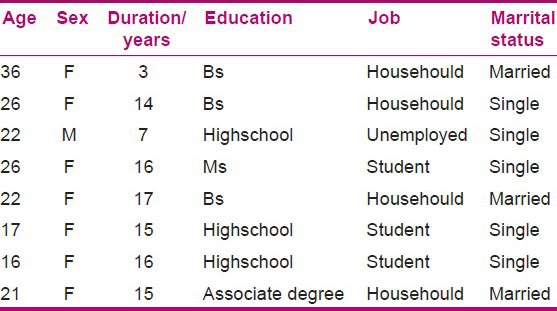

Table 1.

Demographic charectristics of participants with type 1 diabetes

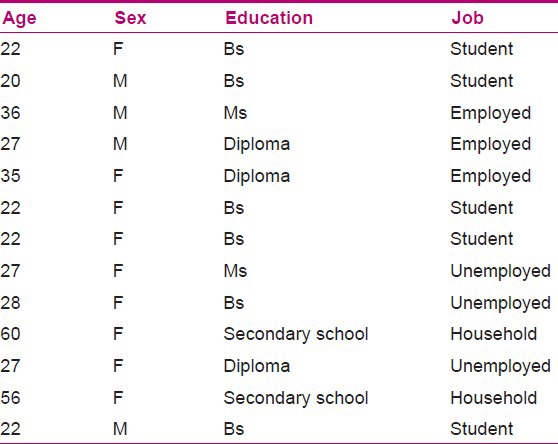

Table 3.

Demographic charectristics of participants without diabetes

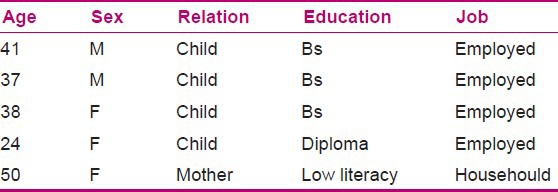

Table 2.

Demographic charectristics of family members

Data collection

After getting consent to participate in the study, the people without diabetes were asked to answer an open question: “What do you think about a person with type 1 diabetes?” On the other hand, the people with diabetes were asked to respond to the question: “How do people without diabetes think about a person with type 1 diabetes?” Furthermore, each one had to describe his/her feelings and thoughts about him/herself as a person living with type 1 diabetes. The mean time of the interviews was 20-45 min, and all of them were recorded on an MP3 player.

Data analysis

To analyze the data, conventional content analysis was used in the present study. Data were transcribed verbatim immediately after each interview. Then, transcriptions were read several times in order to derive codes, after that words which reflected main thoughts concepts were highlighted. Then, similar codes overlapped and integrated under certain categories. Member checking was undertaken to ensure the data were trustworthy and validated the researchers’ interpretation of the data. After one researcher initially coded, the data participants and co-researchers re-examined the transcripts. In addition, credibility of findings was established by having other researchers independently analyze the raw data and their interpretations were compared with those of the study researchers.

Ethical issues

The approval to conduct the study was granted by the Ethics Committees of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences in Iran. Potential participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary and they could withdraw at any time, their confidentiality would be maintained, and that no individual would be identified in any publications arising from the study.

RESULTS

The findings highlighted that a person with type 1 diabetes in the study context suffers social self-stigma. The noticeable issue is that the participants with diabetes realized all aspects of social stigma including miserable human, candidates of rejected marriage, and deprived of a normal life; however, they only labeled themselves as being deprived of a normal life.

Miserable human

This diabetes-related stigma was the most common stigma in all interviews, which included the subcategories, namely “always sick and unable,” “death reminder,” and “intolerable burden.”

Always sick and unable

Persons with type 1 diabetes are labeled as a sick and disabled person by family members and other people. Moreover, they remembered the sufferings caused by diabetes complications in a person with diabetes, which could be more painful for a young person with type 1 diabetes.

“My father had diabetes which had affected his eyes, kidneys and even his sexual function… he always was sick and disabled to do his work, especially in the last years of his life… My father got the disease from mid-life … could you imagine how it would be for a child or a young adult with type 1 diabetes?… It is surely more devastating and I suppose that they are miserable humans…” (female, 37 years old)

Participants with type 1 diabetes received the public massages and talked about how it is painful to understand the society's views about miserable patient:

“People in school, university, work place or simply everywhere look at you as a patient who can do nothing… It is obvious when they communicate with you as a person with diabetes they only imagine diabetes complications such as amputation and dialysis. I wish they did not see all with this lens… I hope they all do not see diabetics through black lens. I wish they did not look at me as they do about an old man with diabetes that has experienced different complications caused by diabetes. I wish they didn't picture us as people who are always sick, miserable and able to do nothing…”(female, 25 years old).

Death reminder

The participants without diabetes talked about people with diabetes as death reminders: “When I hear a person has diabetes I only imagine the death… I believe that a person with diabetes goes to die day to day… I mean that they do not experience a normal death. In fact, diabetes pushes them to death…” (male, 27 years old)

Surprisingly, people with diabetes understood how people imagine a short life for them because of diabetes. A 22 year-old-man said:

“Public have misconceptions that our life expectancy is too short and all of us will experience death very soon.”

Intolerable burden

Family members and people without diabetes referred to a person with diabetes as a heavy burden that the family has to carry. A mother of a young person with type 1 diabetes said:

“It is too hard for parents… too hard to have a child with diabetes… It is too difficult to see your child is in sickness… not only for diabetes treatment expenditure but also for the stressful life of having a child with diabetes at home… Can you imagine that? It is too hard…”

Another participant with type 1 diabetes put it in plain words:

“I was hospitalized in a short period after my marriage. My Mom has not told my husband for a while that I am in hospital. When he realized he came immediately to hospital and asked my Mom why have you hidden this from me? When I accepted to marry her I accepted to be along with her everywhere… Can you guess what my Mom responded? She said because we were so exhausted of diabetes and do not want you to feel the same. We don't want to see you get tired of the disease and undergo this overwhelming sense……” (female, 20 years old)

Rejected marriage candidate

The participants without diabetes believed that a person with type 1 diabetes (special female) does not deserve marriage. This category included “busy spouse” and “high-risk pregnant.”

Busy spouse

The public preferred to choose a happy life, which is possible in marriage with a healthy person, and not a stressful life because of marrying a person who suffers from diabetes:

“… A wise man looks for a healthy wife, not a sick one who always lives with a disease… In that case you need to live in hospital with her surrounded with numerous problems caused by diabetes… To this everybody prefers to select a healthy spouse not a busy one…” (male, 37 years old)

As a result, public respect the spouse of a person with diabetes as they he/she was a hero in their view:

“I suffer too much when people tell me, ‘Oh! your husband is a hero as he accepted to marry you although you have diabetes….’ It is unbelievable because they tell me he devoted himself by accepting your diabetes… It would be a great human…” (female, 21 years old)

High-risk pregnant

The participants without diabetes thought that a female with diabetes would certainly have a difficult pregnancy with a high possibility of having a child with diabetes:

“The girls with diabetes have to be alone and not to be married because diabetes affects their child…” (female, 60 years old)

People with diabetes, however, received the society's massages; they explained how they try to face different challenges about it:

“My father in-low changed his behavior when he realized that I have diabetes. He told me your child would be a diabetic as you are and we don't want to have grand children… I talked to him several times and explained about diabetes, its risk factors and the low possibility of having a child with diabetes. Now, he behaves with me in a better way; however, I am always worried about my pregnancy and having a baby with diabetes…” (female, 22 years old)

Deprived of a normal life

Not only people without diabetes but also people with diabetes labeled a person with type 1 as being deprived of a normal life. This category included “prisoner of (to must)” and “deprived of pleasure.”

Prisoner of (to must)

The participants explained how people with diabetes are surrounded by many “to must” and “not to must” in living with diabetes.

“They are deprived of many things… They are prohibited from many foods. There are many activities that they need to do in order to control their blood sugar… They always need to analyse their life and it is to hard…” (female, 22 years old)

In addition, another participant with diabetes said:

“Living with diabetes is a hard daily challenge… You need to follow many prescriptions every day to manage your diabetes. All of this is too difficult…” (male, 22 years old)

Deprived of pleasure

The public participants viewed a person with type 1 diabetes as a disabled one who cannot enjoy his/her life.

“A diabetic is like a paraplegia one who cannot eat everything, goes everywhere, and do everything that he/she wishes to do…. He/she is deprived of pleasure and never can experience happiness in life…” (male, 27 years old)

The people with diabetes also labeled themselves in a similar way. One participant stated:

“Public believe that we cannot live in happiness… I believed this too… You know, I always need to be more careful about my diabetes… Sometimes I am not happy as my life isn't like others and I cannot continue it as the people without diabetes do… [long silent]…” (female, 26 years old)

Another participant said:

“I couldn't go outdoors with my friends because I needed to carry my insulin and my Mom didn't let me… I am also unable to fast in Ramadan as my doctor said I cannot do that… You know, I can even experience some usual life pleasures…” (female, 17 years old)

DISCUSSION

The study's findings highlighted that the people without diabetes believed that a person with diabetes is miserable. This is reflected from the “norm to be kind” that has been shown in other studies, for a person who suffers from a physical illness. For example, Shestak found that healthy people try to be kind with people living with diabetes; however, this behavior affects the persons in a negative way.[30]

In the current study, the miserable stigma was a consequence of imagining the person as a sick one always, death reminder, and intolerable burden. Similar findings indicated that the disabling diabetes complications such as coronary artery disease, blindness, kidney disease, etc., can have an effect on the public view about those living with diabetes.[31]

Likewise, the findings of Weiler Dawn (2007) showed that others see people with diabetes as sick patients who are unable to do their daily activities and will certainly experience amputation and a sudden death.[32] However, there are similar attitudes; it seems to be for the first time that people with diabetes were mentioned as death reminder. It was found to be rooted as a negative view about diabetes in Iranian context[33] because of high prevalence of diabetes complications and less known empowered people in Iran. On the other hand, describing the person as an intolerable burden on the family indicates that people with type 1 diabetes have less responsibility about diabetes control in comparison with the family members in this context.

Current findings showed that women with type 1 diabetes are high-risk in pregnancy and rejected marriage candidate. The evidences highlighted that a pregnant with diabetes is at risk for neonatal death and bears the stigma of carrying diabetes to the child.[31] In addition, Cohen et al. (1993) indicated that diabetes is a barrier in social relationships such as divorce, infertility, and sexual problems.[34] The study of Khoury (2006) in Middle East showed that having diabetes is associated with shame and embarrassment for both men and women. This psychological response is because of public belief of sexual dysfunction in men with diabetes. This is also associated with fear of infertility in women.[35] On the contrast, Goenka et al. (2004) indicated negative impacts of diabetes on girls’ marriage in South Asia. In fact, families prefer to choose a healthy wife with no restriction in having and bearing a child.[36] This is very similar to what happens in Iranian society.[33] Abdoli et al. (2011) believed that this could be a result of a strong belief that being healthy is necessary to play parental and spousal roles perfectly. Furthermore, having a child is an important aspect of life, which cannot be ignored easily by Iranians.[8]

A common diabetes-related stigma in people with or without diabetes was that the diabetics are deprived of a normal life. Naemiratch and Manderson (2008) found that the phrase of “Normal… But” was a familiar one in those with diabetes in Thailand. They concluded that people by saying “Normal… But” indicated that their lives are normal; however, they realized how important it is to consider the disease limitations.[37]

The findings have highlighted that diabetes type 1 related stigma is an important issue in Isfahan. This fact makes it compulsory to overcome diabetes-related stigma in the context.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for the support (grant no. 290165) and all people with or without diabetes for assisting in the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Science

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler PM, Arnold MS, Fitzgerald JT, Feste CC. Patient empowerment: Result of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:943–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pibernik-Okanovic M, Prasek M, Poljicanin-Filipovic T, Pavlic-Renar I, Metelko Z. Effects of an empowerment-based psychosocial intervention on quality of life and metabolic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:193–9. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson R, Funnell M. 2nd ed. New York: American Diabetes Association; 2005. The art of empowerment. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viklund G, Ortqvist E, Wikblad K. Assessment of an empowerment education programme. A randomized study in teenagers with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2007;24:550–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paterson B. Myth of empowerment in chronicillness. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:574–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kralik D, Brown M, Koch T. Women's experiences of being diagnosed with a long-term illness. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33:594–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdoli S. Tehran: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 2008. The empowerment process in people with Diabetes, in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez CA, Antone I, Cornelius I. A grounded theory study of the experience of type 2 diabetes mellitus in First Nation adults in Canada. J Transcult Nurs. 1999;10:220–8. doi: 10.1177/104365969901000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aujoulat I, Marcolongo R, Bonadiman L, Deccache A. Reconsidering patient empowerment in chronic illness: A critique of models of self-efficacy and bodily control. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1228–39. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdoli S, Ashktorab T, Ahmadi F, Parvizy S. Diabetes diagnosis; disrupter identity. IJEM. 2011;13:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke P, Reitzes D. The link between identity and role performance. Soc Psychol Q. 1981;44:83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stets J, Burke P. Identity theory and social identity. Soc Psychol Q. 2000;63:224–37. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keicolt K. Stress and the decision to change oneself: A theoretical model. Soc Psychol Q. 1994;57:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cast A, Stets J, Burke P. Does the self conform to the views of others? Soc Psychol Q. 1999;62:68–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.West ML, Yanos PT, Smith SM, Roe D, Lysaker PH. Prevalence of internalized stigma among persons with severe mental illness. Stigma Res Action. 2011;1:3–10. doi: 10.5463/sra.v1i1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Link BG, Phelan J. On stigma and its public health implications, in stigma and global health: Developing a research agenda. 2001. Available from: http://www.stigmaconference.nih.gov/FinalLinkPaper.html .

- 17.Dwivedi A. Living on the outside: The impact of diabetes-related stigma. 2008. [Last cited in 2011]. Available from: http://www.citizen.news.org .

- 18.Weiss M, Ramakrishna J. Stigma interventions and research for international health. Lancet. 2006;367:536–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalra B, Kalra S, Sharma A. Social stigma and discrimination: A care crisis for young women with diabetes in India. Diabetes Voice. 2009;54(special issue):37–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son H, Yi M, Ko M. USA: University lllinois; 2011. May, Psychosocial adjustment of people with diabetes in Korea, 7th international congress of qualitative inquiry. 17th-21st. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bharti K, Sanjay K, Amit K. Social stigma and discrimination: A care crisis for young women with diabetes in India. Diabetes Voice. 2009;54:37–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aonoa S, Matsuura N, Amemiya S, Igarashi Y, Uchigata Y, Urakami T, et al. Marriage rate and number of children among young adults with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Japan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;49:135–41. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(00)00137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdoli S, Ashktorab T, Ahmadi F, Parvizi S, Dunning T. The empowerment process in people with diabetes: An Iranian perspective. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;55:447–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdoli S. Diabetes: “Defect Point” or “Positive Opportunity”. ME-JN. 2011;5:22–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tilden B, Charman D, Sharples J, Fosbury J. Identity and adherence in a diabetes patient: Transformations in psychotherapy. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:312–24. doi: 10.1177/1049732304272965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Millen N, Walker C. Adelaide: Flinders University; 2000. Overcoming the stigma of chronic illness: Strategies for ‘straightening out’ a spoiled identityin Sociological Sights/Sites TASA Conference. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kralik D. The quest for ordinaries: Transition experienced by midlife women living with chronic illness. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39:146–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abolhasani S, Babaie S, Eghbali M. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2008. Mothers experience about self care in children with diabetes. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amini P. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2003. Study of problems in children and adolesence living with diabetes from their mothers’ perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shestak A. US: The impact of stigma on reactions to an individual with type 1 diabetes, in nursing school, Carnegie Mellon University; Available from: http://shelf1.library.cmu.edu/HSS/a986117/a986117.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hopper S. Diabetes as a stigmatized condition: The case of low-income clinic patients in the United States. Soc Sci Med Med Anthropol. 1981;15B:11–9. doi: 10.1016/0160-7987(81)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weiler Dawn M. USA: The University of Arizona; 2007. The socio-cultural influences and process of living with diabetes for the migrant latino adult, in Nursing schoo. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdoli S, Mardanian L, Mirzaie M. Howpublic persept diabetes; a qualitative study. IJNMR. 2012:17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen MZ, Tripp-Reimer T, Smith C, Sorofman B, Lively S. Explanatory models of diabetes: Patient practitioner variation. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90300-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khoury SV. Cultural approach to diabetes therapy in the Middle East. Diabetes Voice. 2001;46:21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goenka N, Dobson L, Patel V, O’Hare P. Cultural barriers to diabetes care in south Asians: Arranged marriage arranged complications? Pract Diabetes Int. 2004;21:154–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Naemiratch B, Manderson L. ’Normal, but…: Living with type 2 diabetes in Bangkok, Thailand. Chronic Illn. 2008;4:188–98. doi: 10.1177/1742395308090069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]