Abstract

Background:

Renal fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) has become an uncommon procedure in the era of renal helical computed tomography (CT), which has high diagnostic accuracy in the characterization of renal cortical lesions. This study investigates the current indications for renal FNAB. Having knowledge of the specific clinico-radiologic scenario that led to the FNAB, cytopathologists are better equipped to expand or narrow down their differential diagnosis.

Materials and Methods:

All renal FNABs performed during a 6 year interval were retrieved. Indication for the procedure was determined from the clinical notes and radiology reports.

Results:

Forty six renal FNABs were retrieved from 43 patients (14 females and 29 males with a mean age of 52 years [range, 4-81 years]). Twenty one cases (45.6%) were performed under CT-guidance and 25 cases (54.4%) under US-guidance. There were four distinct indications for renal FNAB: (1) solid renal masses with atypical radiological features or poorly characterized on imaging studies due to lack of intravenous contrast or body habitus (30.2%); (2) confirmation of radiologically suspected renal cell carcinoma in inoperable patients (advanced stage disease or poor surgical candidate status) (27.9%); (3) kidney mass in a patient with a prior history of other malignancy (27.9%); and (4) miscellaneous (drainage of abscess, indeterminate cystic lesion, urothelial carcinoma) (14.0%). 36 patients (83.7%) received a specific diagnosis based on renal FNAB cytology.

Conclusions:

Currently, renal fine needle aspiration remains a useful diagnostic tool in selected clinico-radiologic scenarios.

Keywords: Fine needle aspiration biopsy, imaging modalities, indications, radiology, renal

BACKGROUND

Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) is a safe, rapid and widely accepted procedure to sample a mass lesion. At our institution, however, we have observed that renal FNAB has become an uncommon procedure, despite the fact that the number of FNABs performed on other deeply seated abdominal organs has been increasing steadily. This trend has been observed by other institutions as well.[1] This disparity is due to the introduction of dedicated renal helical computed tomography (CT), which is the contemporary modality of choice for detection of suspected renal masses and for characterization of known renal tumors.[2,3] Owing to the high diagnostic accuracy of renal helical CT, treatment is routinely implemented based on radiologic findings alone without the need for pathologic confirmation. Renal helical CT has 100% sensitivity for detection of all renal lesions and 95% specificity in identifying renal cell carcinomas.[2,4]

Considering the success of renal helical CT, it would appear that renal FNAB cannot significantly improve on the excellent diagnostic accuracy of cross-sectional imaging modalities and is unlikely to influence the clinical management.[5,6] However, we continue to receive requests for renal FNAB, albeit sporadically. The objective of this study is to identify the indications for performing a renal FNAB at our institution and to determine if there is still a role for this procedure in the era of modern renal imaging modalities. Having knowledge of the specific clinico-radiologic scenario that led to the FNAB, we as practicing cytopathologists are better equipped to expand or narrow down our differential diagnosis, better prepared to request material for ancillary studies and can thus better serve our clinician colleagues and ultimately the patient.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All renal FNABs performed at our institution between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2010 were retrieved through a computerized search. For each case, the following information was obtained from the pathology and radiology reports: demographic data, cytologic diagnosis, surgical excision follow-up, tumor size and laterality, method of sample collection (ultrasound [US]-guided versus CT-guided), radiologic description of the mass including radiologic impression and differential diagnosis. Clinical notes available in the electronic medical records were reviewed to identify pertinent patients’ histories of other relevant medical conditions (prior or concomitant history of malignancy, end-stage renal disease, dialysis treatment and duration). In each case, the indication to perform the renal FNAB was determined from the radiology reports or clinical notes.

The kidney masses were sampled by fine needle aspiration (FNA) using 22 gauge needles and/or core needle biopsy (CNB) using 18-20 gauge biopsy needles. The aspirated material was used for air-dried and alcohol-fixed smear slides and the needle was then rinsed in RPMI solution for cell block. The material from the CNB was touched on glass slides for imprints, before being fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. In our institution, cases with both FNA and CNB material are processed under the same accession number. For all the cases, a cytopathologist was present on site at the time of procedure to assess the adequacy of the material on air-dried Diff-Quik® stained slides. Immunohistochemical stains were performed on needle rinse cell block or CNB in selected cases.

To determine the material adequacy for this study, aspiration smear slides, needle rinse cell blocks, touch imprint slides or core needle biopsies were reviewed in all cases by both authors. Cases with non-diagnostic cytologic interpretation were analyzed to determine if this result was due to technical failure (acellular sample or insufficient number of cells to make a definitive diagnosis) or sampling error (only benign renal elements, glomeruli and/or tubules, present).[7,8]

RESULTS

Forty six renal FNABs from 43 patients were retrieved during the 6 year period. By comparison, 229 nephrectomies for tumor were performed in the same time interval at our institution. The study group consisted of 14 females and 29 males with age ranging from 4 years to 81 years (mean 52 years). Twenty one cases (45.6%) were performed under CT-guidance and 25 cases (54.4%) under US-guidance. The right and left kidney were equally sampled. Size of the lesions ranged from 1.0 cm to 19.0 cm (mean 6.0 cm). In one case, the exact size of the kidney mass was not specified in the radiology report.

The clinical and radiologic indications to perform the renal FNAB are summarized in [Table 1] in four distinct categories. Three clinico-radiologic scenarios, each almost in equal proportion, comprised 86% of all indications while the forth category represented only a minority of cases.

Table 1.

Clinical and radiologic indications for performing renal FNAB in 43 patients

Solid kidney masses with atypical/or poorly characterized radiologic features

Solid renal masses with atypical/or poorly characterized radiologic features represented the largest group (15 cases in 13 patients, 30.2%). These masses had either atypical radiologic appearance raising a broad differential diagnosis or could not be adequately characterized on imaging studies due to lack of intravenous contrast substance (in patients with chronic renal disease) or ring artifact secondary to large patient’s body habitus.

Radiologic features considered atypical were: Poor margination of the lesion, questionable involvement of the adrenal gland (raising the possibility of an adrenal neoplasm), atypical pattern of enhancement and vascularity (raising the possibility of oncocytoma or angiomyolipoma with minimal fat), presence of extrarenal extension into retroperitoneum (sarcoma or lymphoma were in the differential diagnosis), fat-containing mass with cystic degeneration and retroperitoneal extension (angiomyolipoma vs. retroperitoneal liposarcoma) or tumor involvement of the inferior vena cava (leiomyosarcoma versus renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus).

As indicated in [Table 1], nine patients (69.2%) received the following diagnoses based on the renal FNAB: Renal cell carcinoma [Figure 1], leiomyosarcoma, metanephric adenoma [Figure 2], malignant B-cell lymphoma of follicular center cell origin and neuroblastoma. The FNAB material was non-diagnostic in 4 cases (30.8%) and no further pathologic follow-up was available. Two patients had repeated FNAB for non-diagnostic samples, one obtained through CT-guidance and the other one obtained through US-guidance. The repeated procedure (performed using a different approach) yielded again non-diagnostic material and no pathologic follow-up was available.

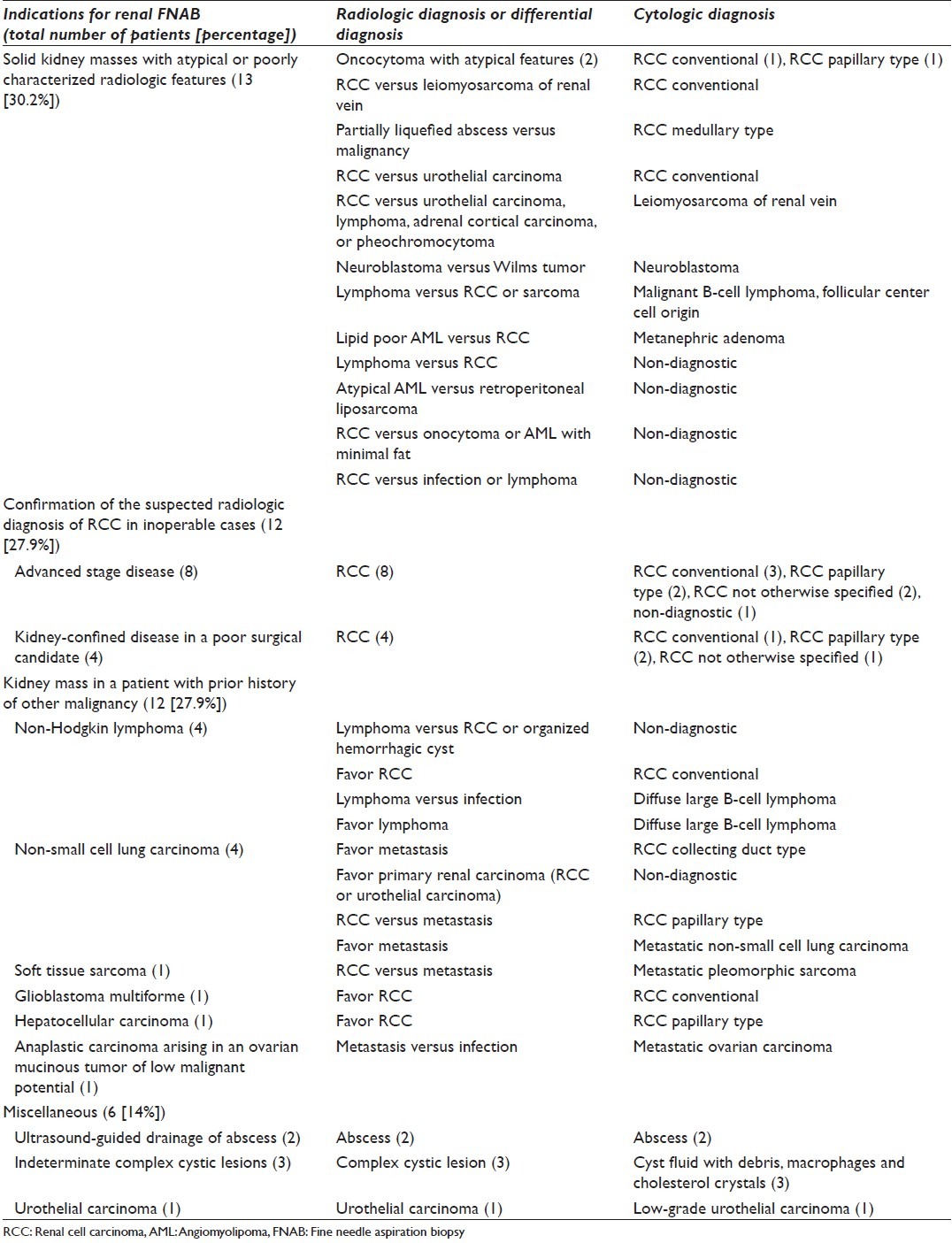

Figure 1.

Medullary renal cell carcinoma. A cluster of cohesive malignant cells displaying high nuclear to cytoplasm ratio and eccentrically placed pleomorphic nuclei with coarse chromatin. Note the mitotic figure and the neutrophils in the background (Diff-Quik stain, ×400)

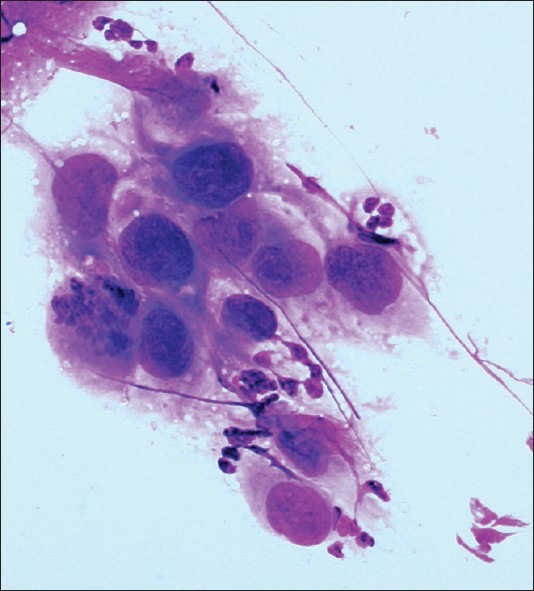

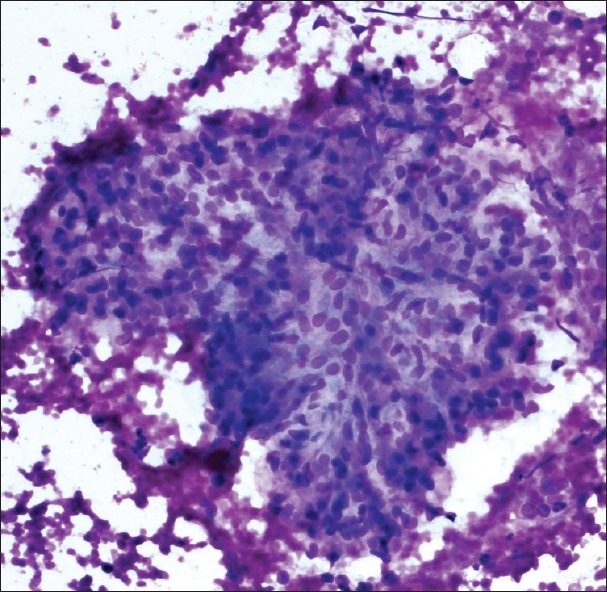

Figure 2.

Metanephric adenoma. The aspirate was very cellular with uniform, hyperchromatic tumor cells with a scant amount of cytoplasm arranged in tight clusters and tubules. The background is clean with no necrosis, mitotic figures, or apoptotic bodies. Tumor cells were positive for WT-1 and CD57 and negative for CK7 (Diff-Quik stain, ×400)

Confirmation of the suspected radiologic diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma in inoperable cases

Another significant group of patients (27.9%) required pathologic confirmation of the suspected radiologic diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma. The indications for this pathologic confirmation were advanced stage disease or poor surgical candidate status. Eight patients had advanced disease at the time of renal mass diagnosis with multiple lung nodules (five patients), multiple brain lesions consistent with metastases (one patient), liver, adrenal gland and bone metastases (one patient) and lymphadenopathy (one patient). Four patients had kidney-confined disease but were not good surgical candidates due to repeated cerebrovascular accidents (one patient), significant heart disease with congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, permanent demand ventricular pacer (one patient) and long standing hemodialysis awaiting a kidney transplant with multicystic kidney disease of dialysis and multiple kidney masses (two patients). The diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma was confirmed by FNAB in 11 patients (91.6%). One case was non-diagnostic; this patient was an 81-year-old female with a 5.6 cm left kidney mass with renal vein extension and multiple lung nodules.

Kidney mass in a patient with a prior history of other malignancy

Prior history of other malignancy in a patient diagnosed with a kidney mass represented another common indication for renal FNAB. Twelve patients (27.9%) had a history of other malignancy: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (four patients), non-small cell lung carcinoma (four patients), soft-tissue sarcoma (one patient), glioblastoma multiforme (one patient), hepatocellular carcinoma (one patient) and anaplastic carcinoma arising in an ovarian mucinous tumor of low malignant potential (one patient). Eight of these patients had a single renal mass and the radiologic impression was: Primary renal neoplasm in four patients (3 renal cell carcinoma and 1 urothelial carcinoma), favor metastasis (one patient) and in three patients a differential diagnosis was given including metastatic disease versus renal cell carcinoma, without favoring one particular diagnosis. The other four patients had multiple, bilateral kidney masses and metastatic disease was favored in all patients, although in two patients the possibility of infection was raised in the differential diagnosis.

Cytologic diagnosis by renal FNAB confirmed the presence of metastasis in 5 cases (41.6%) (non-small cell lung carcinoma [Figure 3], soft-tissue sarcoma, anaplastic carcinoma arising in an ovarian mucinous tumor of low malignant potential and renal involvement by systemic lymphoma), primary renal cell carcinoma in 5 cases (41.6%) and was non-diagnostic in 2 cases (16.8%). For one patient with a prior history of non-small cell lung carcinoma and non-diagnostic (benign renal elements only) FNAB, there was no pathologic follow-up for the kidney lesion; however, abdomen CT-scan repeated at 2 months after the biopsy showed enlargement of the mass with filling of the renal pelvis and ureter to the level of ureterovesical junction and severe hydronephrosis consistent with urothelial carcinoma. The patient with a concomitant diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and non-diagnostic (acellular debris only) FNAB, had a 1.8 cm enhancing solid renal mass with no uptake on PET scan; the mass had been stable for 2 years. Two months after the renal FNAB, patient underwent a partial nephrectomy that revealed an organized hemorrhagic cyst.

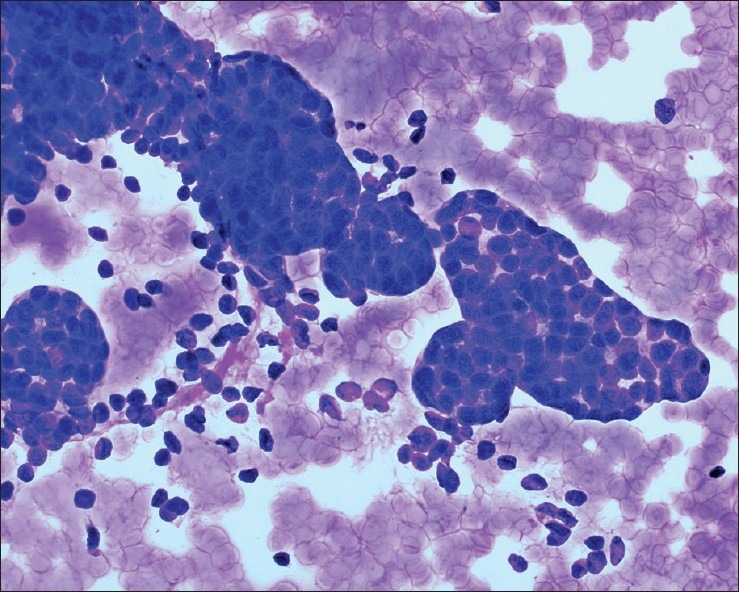

Figure 3.

Metastatic lung squamous cell carcinoma. Malignant cells with distinct cell borders, moderate amount of dense cytoplasm and significant nuclear atypia. Tumor cells were positive for CK5 and P63. Patient had a known history of lung squamous cell carcinoma (Papanicolaou stain, ×600)

Miscellaneous

A few other clinico-radiologic scenarios without a commonality and which cannot be easily categorized or grouped into the other situations were less frequently encountered. These scenarios were: Renal abscess drainage under US -guidance (two patients), indeterminate complex cystic lesions (three patients) and suspicion of urothelial carcinoma (one patient). It is unusual to sample a renal pelvis urothelial carcinoma by FNAB; however, this patient was a 57-year-old male with hematuria and a filling defect in the left upper calyx identified on retrograde pyelogram, in which the traditional sampling methods (ureteroscopy with biopsy, washing and brushing cytology) had been non-diagnostic.

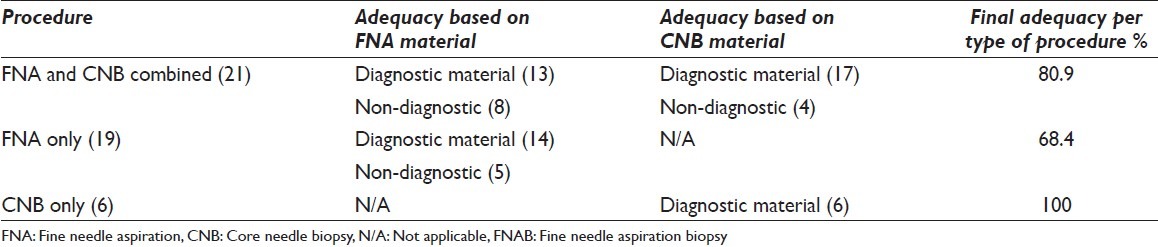

Cytologic work-up of cases

Twenty one cases (45.6%) had FNA and CNB performed combined during the same procedure, 19 cases (41.3%) were obtained by FNA only and in 6 cases (13.1%) solely CNB was performed. Adequate diagnostic material was obtained in 37 FNAB cases (80.4%). [Table 2] summarizes the distribution of adequate material for interpretation based on the type of procedure. As the table shows combined FNA and CNB procedures resulted in higher material adequacy than FNA alone. The addition of CNB material to the FNA material was contributory in four cases, raising the adequacy from 61.9% (13 cases with diagnostic material) to 80.9% when the two methods were used in combination.

Table 2.

Adequacy of 46 renal FNAB based on the type of procedure (FNA versus CNB)

We have observed however, a high rate of non-diagnostic specimens (19.6%, consisting of 9 cases from seven patients). Further investigation into these non-diagnostic cases revealed that 3 of them (33.3%) were due to sampling error [Figure 4], all being obtained via US-guidance. The remaining 6 non-diagnostic cases were due to technical failure (acellular debris, cyst fluid with macrophages, rare atypical cells of unknown significance, or rare spindle cells) with 80% of these cases obtained via CT-guidance.

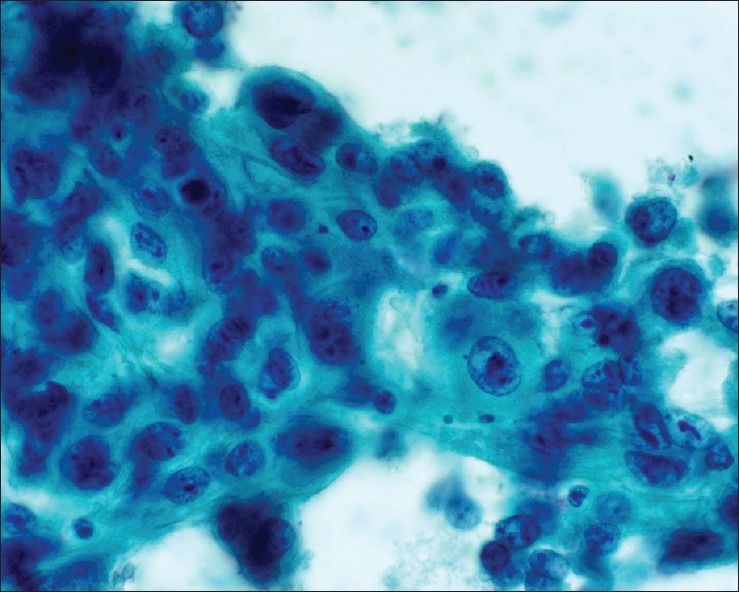

Figure 4.

Normal renal glomerulus. Cellular group with distinctly lobulated contours. Although the cells are bland, the cellularity and three dimensional architecture may create confusion with a neoplasm (Diff-Quik stain, ×200)

The number of cases is more than the total number of patients in the study as three patients had repeated FNAB: One patient had US-guided FNAB of two different abscesses in the same kidney, another patient had FNAB of both kidneys and the third patient had repeated FNAB of the same lesion.

In 13 cases, (28.2%) additional work-up included immunohistochemical studies; in the majority of situations using the CNB material (76.9%) rather than needle rinse cell block material.

DISCUSSION

This study has identified three clinico-radiologic indications to perform renal FNAB that stand out as being most commonly encountered in our current practice. Two indications are known and well-documented in the literature: (1) to confirm the radiologically suspected diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma in patients with advanced stage disease or poor surgical candidates and (2) to evaluate a kidney mass in patients with a prior history of other malignancy.[8–14]

However, only tangentially mentioned in some studies[1,12,13,15] is a third indication identified in our study, that is FNAB of solid kidney masses with atypical/or poorly characterized radiologic features. Although it is not very well-recognized in the literature, it deserves to be acknowledged as it seems to be as common as the more traditional indications. For example, in their study of 31 solid renal masses, Garcia-Solano et al., had four (12.9%) radiologically indeterminate lesions, which on total nephrectomy all proved to be renal cell carcinoma.[1] Likewise, Caoili et al., studying the utility of sonographically guided percutaneous core biopsy in 26 patients had 5 renal masses (19.2%) with radiologically atypical features causing diagnostic uncertainty.[12] One of these patients was diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma; for the other four patients the specific diagnosis was not mentioned, but it is presumed to have been benign. In another study on the utility of FNAB in 43 solid renal masses, Kelley et al., identified a subgroup of 14 patients (33%) with radiographically problematic lesions.[15] Nine of these patients had renal cell carcinoma, three had a benign lesion (renal cyst, fibromatosis, pyelonephritis) and two had a non-renal malignancy. In our study, in the group of solid atypical kidney masses (30.2%) four patients out of the nine (44.4%) with diagnostic cytology had a common type of renal cell carcinoma. The other four adult patients (44.4%) had uncommon diagnoses ranging from benign (metanephric adenoma) to unusual malignant tumors (medullary type renal cell carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma of renal vein, malignant B-cell lymphoma).

Atypical solid kidney masses present a challenge for definitive radiologic characterization for several reasons. First, a solid kidney mass may be classified as radiologically atypical due to questionable involvement of adjacent structures (adrenal gland, inferior vena cava, retroperitoneum). Second, features intrinsic to the mass (margination, vascularity, enhancement pattern) may appear radiologically atypical. Third, the mass may be incompletely/only partially evaluated radiologically. This last situation was encountered in our study in patients with chronic renal failure that had solid kidney masses and intravenous contrast substance was contraindicated. In these patients, magnetic resonance imaging could not be used as an alternate imaging modality as gadolinium-based contrast agents have been implicated in nephrogenic systemic fibrosis when used in patients with renal failure.[2] Therefore, there is a group of patients with chronic renal disease on hemodialysis who are at risk of developing multiple, bilateral renal cell carcinomas, but these patients cannot be completely evaluated by cross-sectional renal imaging modalities. Likewise, we have encountered a patient with incompletely characterized solid kidney mass due to artifacts created by the large body habitus.

Overall, data indicates that in this specific clinico-radiologic scenario the radiologic differential diagnosis is broad and the final cytologic diagnosis can range from benign entities to unusual malignant tumors. As practicing cytopathologists we need to be aware of this distinct indication for renal FNAB and the associated broad differential diagnosis so that we will be prepared to obtain material for needed ancillary studies.

In our study, using dedicated helical CT with renal protocol, radiologic imaging identified 12 patients (27.9%) with renal masses suspected to be renal cell carcinoma. Nearly 91.6% of these were confirmed on cytology to be renal cell carcinoma with one patient having a non-diagnostic sample. As practicing pathologists interpreting a FNAB from a radiologically suspected renal cell carcinoma, we are more likely to confirm this impression cytologically rather than diagnose a completely different entity.

It is interesting to observe that this more traditional indication for renal FNA (i.e. to confirm the diagnosis in radiologically suspected advanced cases of renal cell carcinoma) has decreased in frequency. In the aforementioned study of Kelley et al., from more than a decade ago, 67% of their patients had inoperable disease (27 patients with stage IV renal cell carcinoma and 2 patients with non-renal malignancies).[15] This is in great contrast with our study, in which only 18.6% of patients had advanced stage renal cell carcinoma. A possible explanation is that currently, with the routine use in general medical practice of contrast-enhanced helical abdominal CT scans, approximately 70% of renal cell carcinomas are discovered incidentally[2,3,16] and are presumably likely to be low stage.

It is useful to understand how dedicated helical CT with renal protocol is so effective in the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma, so that we may better understand those situations that still require FNAB of a kidney mass. The dedicated helical CT with renal protocol registers multiple features of any kidney mass (presence of fat and calcifications, baseline density Hounsfield unit measurement, consistency [solid versus cystic], vascularity, enhancement, margins, involvement of anatomic structures) through a series of pre-contrast (unenhanced) and post-contrast (enhanced) images collected at a specific time intervals after intravenous contrast administration. Using strict CT criteria to interpret and integrate all these tumor features, high accuracy (100% sensitivity and 95% specificity) in characterization of renal cortical tumors is achieved.[2,4,16,17] It is important to point out that routine abdominal CT scans are obtained only during the very early phase of renal enhancement and the later critical images are not recorded.[2,3,16] These later images are particularly useful for the detection of small, centrally located (medullary) masses.[2,3,17]

In the past, radiologically indeterminate partially cystic lesions were a common indication for renal FNAB; however, with the advances of cross-sectional imaging modalities, the vast majority of these lesions are currently not aspirated.[11] This trend is also reflected in our study where the indeterminate complex cystic lesions represented only a minority of cases (6.9%).

Our study confirms the well-recognized role of FNAB in the evaluation of suspected kidney metastases, which represented 27.9% of all indications for renal FNAB. Metastases were confirmed in 11.6% of patients. In general, metastases to the kidney are common with incidence ranging from 8% to 13% in autopsy studies;[14,18,19] however, rarely clinically evident as the majority of patients retain normal renal function.[19]

In a large study of 261 renal FNAs, the overall incidence of metastasis to the kidney was 11% with the most common primary tumor being lung carcinoma followed by malignant lymphoma.[14] Other reported primary tumors metastatic to the kidney are less common: hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, cervix carcinomas,[14] malignant melanoma and opposite kidney renal cell carcinoma.[18–21]

Renal FNAB is still required in patients with a prior history of other malignancies if there is a discrepancy between the clinical presentation and CT findings.[18,19] In general, metastatic lesions to the kidney are multiple, bilateral, hypovascular, small, nodular, contained within the kidney contour and homogeneous.[18,19,20,22] Renal lesions with this appearance in a patient with a prior history of other malignancy should be considered metastases until proven otherwise.[20] On the other hand, primary renal cell carcinomas are solitary, large, exophytic, bulging out from the kidney contour, hypervascular and heterogeneous.[18,19] However, in reality, there is an ample range of CT appearances for lesions metastatic to the kidney[21] leading to several important radiologic interpretation problems, specifically to distinguish them from lymphoma, bilateral renal cell carcinoma, multiple renal infarcts or multiple areas of renal/or perirenal inflammation or infection.[18–21] Although the clinical presentation and evolution can help in distinguishing these possibilities, there are situations in which a FNAB is still needed to establish the proper diagnosis, such as: (1) large solitary renal mass and no evidence of metastatic disease elsewhere or (2) multiple renal lesions that on CT do not have the typical appearance of metastases as described above.[20]

Another indication for renal FNAB mentioned in the literature is to confirm a malignant diagnosis before performing percutaneous ablation of a kidney mass.[10,16,23] Radiofrequency and cryoablation have been recently introduced into clinical practice as a treatment modality for a renal mass that has the advantage to preserve the renal function. However, long-term comparison data with the standard of care treatment (partial or total nephrectomy) is still being collected[16] and we do not have any experience with ablative techniques at our institution.

It is evident from our study and also from prior literature that if sufficient diagnostic material is procured at the time of the procedure, renal FNAB is very useful in clarifying certain clinico-radiologic dilemmas. The rate of non-diagnostic specimens in our study was 19.6%, which is similar to that reported by previous studies ranging from 6% to 20%, even when a cytotechnologist is present on site for adequacy assessment.[13,23] The non-diagnostic samples may be due to technical failure (acellular sample or insufficient cells to make a conclusive diagnosis) or sampling error (aspirating only adjacent benign renal epithelial cells).[7] It has been suggested by some authors that the non-diagnostic rate can be improved by using CNB and FNA in combination[24] or by using larger gauge needles.[7,12,25] This is our experience as well, when FNA and CNB are concomitantly used in the same case the adequacy rate increases from 61.9% to 80.9%. Given the adequacy of CNB only cases (100%), obtaining CNB material is preferable if molecular diagnostic tests to subtype renal tumors will be performed.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, currently at our institution renal FNAB is more commonly used to: (1) evaluate solid kidney masses with atypical/or poorly characterized radiologic features; (2) confirm the radiologically suspected diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma in inoperable patients; and (3) evaluate kidney masses in patients with a prior history of other malignancy. In the context of these distinct clinico-radiologic scenarios, renal FNAB remains a valuable diagnostic tool.

COMPETING INTERESTS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

All authors of this article declare that we qualify for authorship as defined by ICMJE http://www.icmje.org/#author.

Each author has participated sufficiently in the work and takes public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content of this article.

ED conceived of the study. ED and LL participated in its design and data acquisition. ED and LL analyzed and interpreted the data. ED drafted the article. All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Each author acknowledges that this final version was read and approved.

ETHICS STATEMENT BY ALL AUTHORS

This study was conducted with approval from Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the institution associated with this study.

Authors take responsibility to maintain relevant documentation in this respect.

EDITORIAL/PEER-REVIEW STATEMENT

To ensure the integrity and highest quality of CytoJournal publications, the review process of this manuscript was conducted under a double-blind mode (authors are blinded for reviewers and vice versa) through automatic online system

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors would like to thank Mrs. Patricia R. Strong, Director of Writing Center and Assistant Professor in University College at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia for critical review of the manuscript and useful suggestions.

Footnotes

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.cytojournal.com/text.asp?2013/10/1/15/115093

Contributor Information

Ema A Dragoescu, Email: edragoescu@mcvh-vcu.edu.

Lina Liu, Email: lliu@mcvh.vcu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.García-Solano J, Acosta-Ortega J, Pérez-Guillermo M, Benedicto-Orovitg JM, Jiménez-Penick FJ. Solid renal masses in adults: Image-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology and imaging techniques - “Two heads better than one?”. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:8–12. doi: 10.1002/dc.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bach AM, Zhang J. Contemporary radiologic imaging of renal cortical tumors. Urol Clin North Am. 2008;35:593–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuh BI, Cohan RH. Different phases of renal enhancement: Role in detecting and characterizing renal masses during helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:747–55. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.3.10470916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopka L, Fischer U, Zoeller G, Schmidt C, Ringert RH, Grabbe E. Dual-phase helical CT of the kidney: Value of the corticomedullary and nephrographic phase for evaluation of renal lesions and preoperative staging of renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1573–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.6.9393168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell SC, Novick AC, Bukowski RM. Renal tumors. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Walsh PC, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 1567–637. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dechet CB, Zincke H, Sebo TJ, King BF, LeRoy AJ, Farrow GM, et al. Prospective analysis of computerized tomography and needle biopsy with permanent sectioning to determine the nature of solid renal masses in adults. J Urol. 2003;169:71–4. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andonian S, Okeke Z, VanderBrink BA, Okeke DA, Sugrue C, Wasserman PG, et al. Aetiology of non-diagnostic renal fine-needle aspiration cytologies in a contemporary series. BJU Int. 2009;103:28–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truong LD, Todd TD, Dhurandhar B, Ramzy I. Fine-needle aspiration of renal masses in adults: Analysis of results and diagnostic problems in 108 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20:339–49. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199906)20:6<339::aid-dc4>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman SG, Gan YU, Mortele KJ, Tuncali K, Cibas ES. Renal masses in the adult patient: The role of percutaneous biopsy. Radiology. 2006;240:6–22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2401050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahni VA, Silverman SG. Biopsy of renal masses: When and why. Cancer Imaging. 2009;9:44–55. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2009.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renshaw AA, Granter SR, Cibas ES. Fine-needle aspiration of the adult kidney. Cancer. 1997;81:71–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caoili EM, Bude RO, Higgins EJ, Hoff DL, Nghiem HV. Evaluation of sonographically guided percutaneous core biopsy of renal masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:373–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.2.1790373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood BJ, Khan MA, McGovern F, Harisinghani M, Hahn PF, Mueller PR. Imaging guided biopsy of renal masses: Indications, accuracy and impact on clinical management. J Urol. 1999;161:1470–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68929-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gattuso P, Ramzy I, Truong LD, Lankford KL, Green L, Kluskens L, et al. Utilization of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of metastatic tumors to the kidney. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:35–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199907)21:1<35::aid-dc10>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley CM, Cohen MB, Raab SS. Utility of fine-needle aspiration biopsy in solid renal masses. Diagn Cytopathol. 1996;14:14–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199602)14:1<14::AID-DC4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uppot RN, Silverman SG, Zagoria RJ, Tuncali K, Childs DD, Gervais DA. Imaging-guided percutaneous ablation of renal cell carcinoma: A primer of how we do it. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:1558–70. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lockhart ME, Smith JK. Technical considerations in renal CT. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:863–75. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(03)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honda H, Coffman CE, Berbaum KS, Barloon TJ, Masuda K. CT analysis of metastatic neoplasms of the kidney. Comparison with primary renal cell carcinoma. Acta Radiol. 1992;33:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volpe JP, Choyke PL. The radiologic evaluation of renal metastases. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1990;30:219–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitnick JS, Bosniak MA, Rothberg M, Megibow AJ, Raghavendra BN, Subramanyam BR. Metastatic neoplasm to the kidney studied by computed tomography and sonography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:43–9. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198501000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Campodonico F. Computed tomography of renal metastases. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1997;18:115–21. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(97)90055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herts BR. Imaging guided biopsies of renal masses. Curr Opin Urol. 2000;10:105–9. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heilbrun ME, Zagoria RJ, Garvin AJ, Hall MC, Krehbiel K, Southwick A, et al. CT-guided biopsy for the diagnosis of renal tumors before treatment with percutaneous ablation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1500–5. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane BR, Samplaski MK, Herts BR, Zhou M, Novick AC, Campbell SC. Renal mass biopsy - A renaissance? J Urol. 2008;179:20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson PT, Nazarian LN, Feld RI, Needleman L, Lev-Toaff AS, Segal SR, et al. Sonographically guided renal mass biopsy: Indications and efficacy. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:749–53. doi: 10.7863/jum.2001.20.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]