Abstract

The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer disease (AD) have not been well been studied in Arab populations. In a door-to-door study of all residents aged ≥65 years in Wadi-Ara, an Arab community in northern Israel, we estimated the prevalence of AD, MCI and the risk of conversion to AD. Subjects were classified as cognitively normal, MCI, AD or other based on neurological and cognitive examination (in Arabic). MCI subjects were re-examined (interval ≥1 year) to determine conversion to AD and contributions of age, gender and education to the probability of conversion. Of the 944 participants (96.6% of those approached; 49.4% men), 92 (9.8%) had AD. An unusually high prevalence of MCI (n=303, 32.1%) was observed. Since the majority of women (77.2%) had no schooling, we estimated the effect of gender on the risk of AD and MCI among subjects without schooling and of school years among men. Among subjects with no schooling (n=452), age (p=0.02) and female gender (p<0.0001) were significant predictors of AD, whereas risk of MCI increased only with age (p=0.0001). Among men (n=318), age increased the risk (p<0.0001), school years reduced the risk of AD (p=0.039) and similarly for MCI [age (p=0.0001); school years (p=0.0007)]. Age (p=0.013), but not gender or school years, was a significant predictor of conversion from MCI to AD (annual rate 5.7%).

The prevalence of MCI and AD are unusually high in Wadi Ara, while the rate of conversion from MCI to AD is low. Yet unidentified genetic factors might underlie this observation.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, prevalence, Arab, risk factors, neuroepidemiology, aging

Introduction

Estimates of prevalence of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) vary and are influenced by demographic characteristics of the population, diagnostic criteria and study methodology [1, 2]. Few epidemiological studies have been carried out in Arabic communities. Wadi-Ara, or the Ara Valley, is a rural area in northern-Israel whose inhabitants are Israeli-Arab citizens. Of note, the elderly population in this community is characterized by high illiteracy and consanguinity rates [3]. Moreover, the population is homogenous with respect to ethnicity (Arabic), religion (Muslim), minimal alcohol consumption, high rates of smoking in men, rural environment and low socioeconomic status [4, 5]. Previously, we reported a remarkably high prevalence of AD in this area [5]. Diagnosis of cognitive impairment in this population carries difficulties. A screening method based on MMSE cutoff scores, which is strongly dependent on education, could generate bias due to the low levels of formal schooling of the Wadi-Ara population, especially amongst women. Considering the high illiteracy rate, we estimated the prevalence of AD and MCI in the elderly population (≥ 65 years) of Wadi-Ara based on clinical assessment. In a subsequent follow-up phase we estimated the conversion rate from MCI to AD and risk factors for this conversion.

Materials and Methods

Study population and setting

We performed a door-to-door observational study with follow-up in Wadi-Ara, an Arab community of 81,400 inhabitants located in northern Israel. All Wadi-Ara residents aged ≥ 65 years on prevalence day (January 1st, 2003) were eligible (n = 2,067, according to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics). There were no other selection criteria. Individuals were ascertained between January 2003 and December 2008 and were subsequently re-evaluated after ≥ 1 year. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Sheba Medical Center according to guidelines from the Israel Ministry of Health and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University Hospitals of Cleveland, Case Western Reserve University, Boston and Louisville University. All participants signed a written consent form in Arabic. The interviewer read the consent form to illiterate subjects who then signed by fingerprinting with the index finger of his/her dominant hand.

Subject Evaluation

This work is part of an epidemiological and genetic study of aging-related brain disorders in Wadi-Ara [6–9]. The research team included a neurologist (M.M.) and an academic nurse (A.A.), both fluent Arabic speakers, who examined all subjects in their homes. All subjects resided either with their spouse or in the home of a close relative. None lived alone and none of the subjects were institutionalized, as is the norm in this population. Information about education (school years), medical and family history, medication use, daily activities (social, personal, occupational and recreational), behavior, cognitive abilities and changes in the above was obtained by a nurse-led structured interview of the subject and a close relative. During the second visit, the neurologist performed a complete neurological examination including the motor part of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale in all subjects. All subjects had medical insurance as required by law in Israel (the National Health Insurance Law, 1995) and regularly attended their family physician’s medical practice. The presence of concomitant diseases was determined by the history, informant history and review of relevant documentation such as medical reports and drug prescriptions. When prescriptions of medications were present, the informants were asked accordingly about the presence of the relevant diseases.

Cognitive Instruments

Arabic translations of the Minimental State Examination (MMSE; maximum score = 30) and the Brookdale Cognitive Screening Test (BCST; maximum score = 24) were used. The BCST was developed at the Brookdale Institute of Gerontology, Jerusalem, Israel, for use in populations with high illiteracy rates [10]. It includes items on orientation, language, memory, attention, naming, abstraction, concept formation, attention, praxis, calculation, right-left orientation and visuospatial orientation. The Arabic versions of the MMSE and the BCST have been validated, and norms have been published [11]. Since the MMSE involves several tasks that are dependent on literacy, these items scored 0 in subjects with no formal education. A highly significant correlation between MMSE and BCST scores in normal subjects has previously been reported by our group (r = 0.85; p <0.0001). This correlation was of the same magnitude for men (r = 0.82) and women (r = 0.85; p < 0.0001 for both) [11].

Subject Classification

All subjects were classified as healthy cognitively normal (CN), AD, MCI, vascular dementia (VD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) dementia, other dementia or not classifiable according to accepted criteria [12–16].

We did not use MMSE and BCST cutoff scores for cognitive classification. A subject was defined as CN if there were no complaints about memory impairment or any other cognitive domain, no evidence of such disturbance according to the informant history or neurological examination, and no evidence of impairment in activities of daily living due to cognitive disturbances [11]. Subjects were classified as MCI if they had an impairment of cognitive function on examination, with a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score of 0.5 [12] and an informant record of cognitive decline, but did not have functional impairment in their activities of daily living that would qualify for dementia when assessed by the informant interview and/or physical examination [13]]. Dementia was diagnosed according to the DSM-IV criteria and those of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10), and AD by the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria for probable or possible AD [14–16]. A diagnosis of VD was established according to the ICD-10 criteria [15].Thus, a history consistent with cerebrovascular disease, pyramidal signs and previous cerebral imaging were actively sought to substantiate a diagnosis of VD [15]. We used Gelb’s criteria for a diagnosis of PD [17]. The category "not classifiable" was assigned to subjects with complex medical conditions or advanced systemic disease in which it could not be determined whether the cognitive impairment was due to the underlying medical condition or the neurodegenerative disease. Three neurologists (M.M., R.S. and R.I.) reviewed the results of the field examination of each subject in a bimonthly conference and formed a consensus diagnosis.

Study design

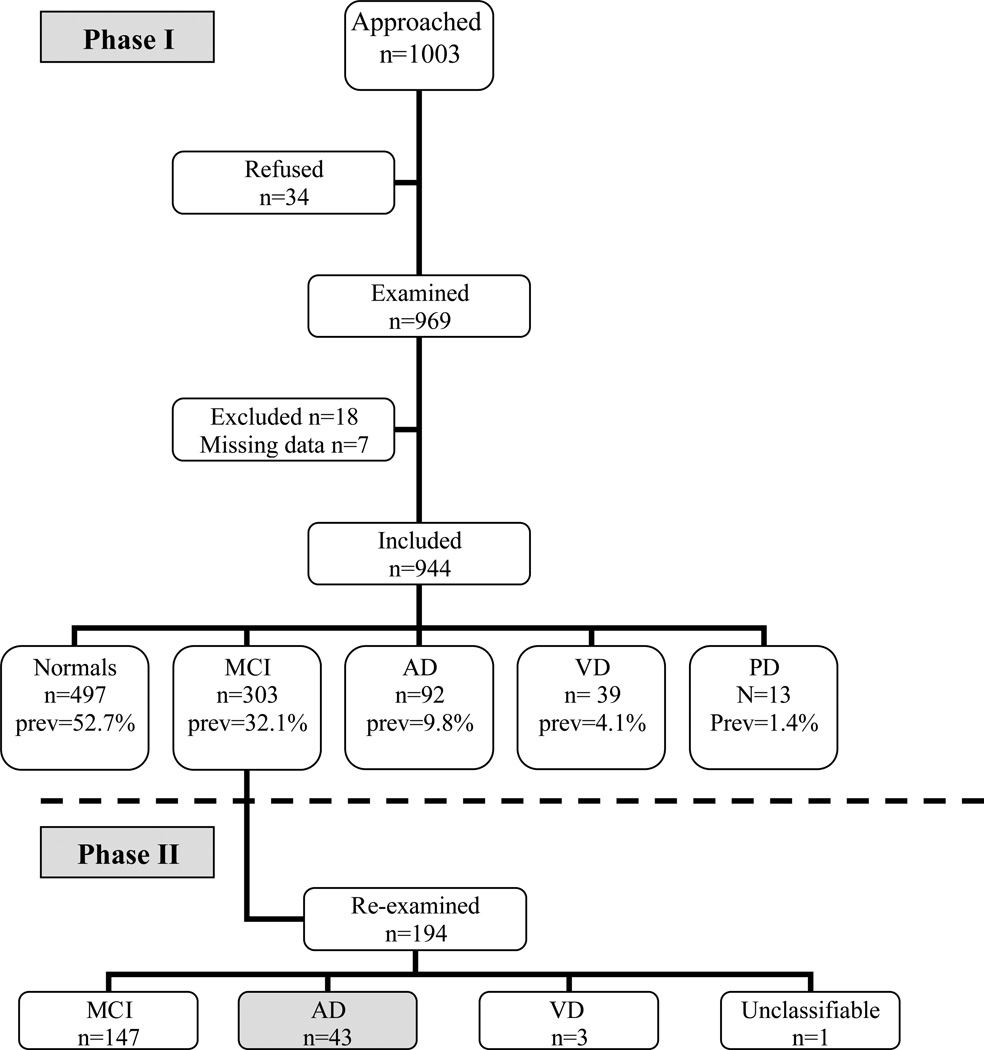

The study was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, we classified all subjects that agreed to participate as CN, MCI, AD, VD or other. In Phase 2, all subjects diagnosed as MCI were reexamined after ≥1 year using the cognitive classifications described above without using any selection criteria. Causes for exclusion were reviewed to account for newly developed confounding comorbidities (e.g. end-stage renal failure or stroke).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Statistical Analysis Software). In Phase 1, we examined the effect of age, gender and years of schooling on the risk of AD and MCI separately using stepwise logistic regression. Illiteracy was defined as zero school years (no schooling). Since the proportion of illiteracy was much higher in women (77.7%) than men (23.8%), the risk of AD or MCI was evaluated in a sub-group of subjects with no schooling as a function of age, gender and their interaction. In order to test for the effect of schooling, another model included men only and the explanatory variables were age, years of schooling and their interaction.

In Phase 2, MCI subjects were re-examined after ≥ 1 year to determine the conversion to AD. We estimated the odds of conversion to AD using a stepwise logistic regression model with age, time interval between the first and second examination, gender, years of schooling and terms for the two-way interactions of these variables. Subjects with missing data for any of the explanatory variables were excluded.

Results

We approached a total of 1,003 subjects aged ≥65 years [figure 1]. Thirty-four subjects (3.4%) refused, and 25 additional subjects (2.8%) were excluded for the following reasons: severe systemic disease (n=9), incomplete data (n=7), aphasia (n=3), mistaken data (n=3), missing data (n=2), and hydrocephalus (n=1). A total of 944 subjects were included in the study including 466 men (49.4%) and 478 women (50.6%). The demographic characteristics and number of school years of the study sample are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Figure 1 shows that more than 45% of the subjects were either demented or cognitively impaired. The prevalence of AD was estimated to be 9.8% (95% CI 8.0–10.2) and prevalence of MCI was estimated to be 32.1% (95% CI 29.0–35.0). The mean age of AD patients (78.5±7.7 years) was higher than the mean ages of MCI patients (72.8±6.1 years, and cognitively normal subjects (70.7±5.5 years). The prevalence estimates were higher in women than men for both AD (14.2% vs. 5.2%) and MCI (37.9% vs. 26.2%).

Figure 1. Study population and design.

AD=Alzheimer's disease, MCI=Mild Cognitive Impairment, VD=Vascular Dementia, prev=Prevalence

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| N (%) | women (%) | men (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 944 | 478 (50.5) | 466 (49.4) | |

| age 65–69 y | 372 (39.4) | 189 (39.5) | 183 (39.3) |

| age 70–79 y | 438 (46.4) | 226 (47.3) | 212 (45.5) |

| age ≥ 80 y | 133 (14.1) | 63 (13.2) | 70 (15) |

Table 2.

School years

| 0 y (%) | 1–4 y | 5–8 y | >8 | Median | Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| all (n=944) | 479 (51) | 221 | 191 | 47 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| male (n=466) | 110 (24) | 156 | 153 | 44 | 4 | 4 (4) |

| women (n=478) | 369 (77) | 65 | 38 | 3 | 0 | 1 (2) |

Rates of AD and MCI were strongly associated with school years. AD was diagnosed in 15.7% of subjects without any formal education versus 2.1% in subjects with ≥8 years of school years and similar results were obtained for MCI (42.2% among illiterate subjects versus 10.6% among those with ≥8 years of education). Only 22.8% of the women versus 76.4% of men had any school education [Table 2]. In order to estimate the contribution of gender independent of school years to the risk of AD or MCI, we evaluated logistic regression models among subjects with no schooling (n=452). This analysis showed that age (p=0.02, OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.14–1.27) and female gender (p<0.0001, OR=2.96, 95% CI 1.2–7.25) were significant predictors of AD, whereas risk of MCI increased only with age (p=0.0001, OR=1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.12). Conversely, in order to estimate the contribution of school years independent of gender to disease risk, we tested models among men only. We found that age increased the risk (p<0.0001, OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.12–1.29) and school years reduced the risk of AD (p=0.039, OR=0.82, 95% CI 0.68–0.99). The risk of MCI also increased with age (p=0.0001, OR=1.08, 95% CI 1.04–1.12), and school years reduced the risk of MCI (p=0.0007, OR=0.81, 95% CI 0.71–0.87).

Of the 194 subjects with MCI that were re-examined in Phase 2. The time interval between cognitive assessments was 47 ± 22 months. Forty-three converted to AD (22.2%), giving an annual conversion rate of 5.7%. Three developed VD, 147 remained MCI, and one was unclassifiable. No MCI subjects reversed to CN at Phase 2. Stepwise regression analysis showed that age (p=0.013, OR=1.12, 95% CI 1.02–1.22) and the interval between examinations (p=0.019, OR=1.02, 95% CI 1.0–1.04) predicted conversion from MCI to AD. Gender and the number of school years were not significant predictors of conversion.

Of note is the fact that the cognitive instruments used in cognitive evaluation were strongly affected by education, especially among women. The mean MMSE and BCST scores are shown in Table 3 and 4, stratified by diagnosis and education level. Norms for MMSE and BCST are also depicted by gender classification. In case of cognitive classification using MMSE norms, 19 men (6.5%) and 24 women (11.8%) diagnosed in this study as cognitively normal, would have been falsely diagnosed as suffering from cognitive decline. Using BCST norms, 17 men (5.8%) and 14 women (6.9%) of the normal-group would have been diagnosed as being cognitively impaired.

Table 3.

MMSE and BCST stratified by schooling in cognitively normal subjects

|

normal n=497 | ||||

| school years |

MMSE mean |

MMSE stdv |

BCST mean |

BCST stdv |

| 0 y | 21.7 | 2.7 | 16.5 | 2.6 |

| 1–4 y | 25.6 | 3.2 | 19.8 | 2.8 |

| 5–8 y | 26.8 | 2.8 | 20.9 | 2.6 |

| ≥8 | 28.5 | 1.8 | 22.5 | 1.9 |

|

normal women | ||||

| school years |

MMSE mean |

MMSE stdv |

BCST mean |

BCST stdv |

| 0 y | 21.3 | 2.9 | 16.1 | 2.7 |

| 1–4 y | 24.9 | 3.1 | 19.2 | 2.8 |

| 5–8 y | 26.9 | 3.4 | 20.9 | 2.6 |

| ≥8 | 25 | 0 | 18.5 | |

|

normal men | ||||

| school years |

MMSE mean |

MMSE stdv |

BCST mean |

BCST stdv |

| 0 y | 22.8 | 1.8 | 17.6 | 1.9 |

| 1–4 y | 25.9 | 3.2 | 20.1 | 2.8 |

| 5–8 y | 26.8 | 2.7 | 20.7 | 2.6 |

| ≥8 | 28.6 | 1.6 | 22.7 | 1.7 |

MMSE=Minimental State Examination, BCST= Brookdale Cognitive Screening Test

Table 4.

MMSE and BCST stratified by schooling in subjects with MCI and AD

| MCI | ||||

| school years |

MMSE mean |

MMSE stdv |

BCST mean |

BCST stdv |

| 0 y | 17.8 | 1.9 | 14.7 | 1.6 |

| 1–4 y | 19.6 | 3.4 | 16 | 2.1 |

| 5–8 y | 19.2 | 3.2 | 15.8 | 2.2 |

| ≥8 | 17.4 | 0.6 | 15.2 | 0.5 |

| AD | ||||

| school years |

MMSE mean |

MMSE stdv |

BCST mean |

BCST stdv |

| 0 y | 12.7 | 3.7 | 11.2 | 3.1 |

| 1–4 y | 12.6 | 6.7 | 9.6 | 5.4 |

| 5–8 y | 13.2 | 2.4 | 13 | 2.8 |

| ≥8 | 16 | 12 | ||

MMSE=Minimental State Examination, BCST= Brookdale Cognitive Screening Test, AD=Alzheimer's disease, MCI=Mild Cognitive Impairment

Discussion

We found a higher prevalence of AD and MCI among Wadi-Ara Arab elders, especially women, than reported in western countries [2] or even compared to populations with similar illiteracy rates [1, 18–35]. We are not aware of any previous study which analyzed the prevalence of MCI and the conversion from MCI to AD in and Arab cohort. In addition, the epidemiology of MCI in populations with high illiteracy rates as ours are reportedly very rare (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prevalence of AD in populations with high illiteracy rates (>20%)

| Country | Ref | Diagnostic criteria | Age cutoff | sample size (n) | n ≥ 65 y | iliteracy (%) | n>65 y (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All dementia | AD | VD | other dem | |||||||

| Asia | ||||||||||

| China | 18 | DSM-IV | 50 | 16.095 | 7194 | 55,4 | 260 (3.6) | |||

| China | 19 | NINCDS-ADRDA | 55 | 34807 | 20655 | 36,1 | 3950 (>55) (11.4) | 703 (2.0) | 236 (0.7) | 316 (0.9) |

| China (Hong Kong) | 20 | DSMIV (AD) | 70 | 1034 | 36 | 99 (9.6) | 64 (6.2) | 29 (2.8) | 6 (0.6) | |

| China (Shanghai) | 21 | DSM III | 55 | 5055 | 3558 | 21,1 | 152 (4.3) | 98 (2.8) | 41 (1.2) | |

| India | 22 | DSM-IV, NINCDS-ADRDA | 55 | 5126 | 2715 | 73,3 | 37 (1.4) | 29 (1.1) | ||

| India | 23 | ICD-10 | 60 | 750 | 91 | 26 (3.5) | 11 (1.5) | 7 (0.9) | 8 (1.1) | |

| Israel | 5 | DSM-IV | 60 | 821 | 72 | 168 (20.5) | ||||

| Korea (rural) | 24 | DSM-III-R, NINCDS-ADRDA, NINDS-AIREN | 65 | 1037 | 61,6 | 74 (7.1) | 45 (4.3) | 26 (2.5) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Korea (Seoul) | 25 | DSM-IV, NINDS-AIREN, NINCDS-ADRDA | 65 | 643 | 41,5 | 40 (6.2) | 25 (3.9) | 9 (1.4) | 6 (0.9) | |

| Qatar | 26 | DSM-IV | - | 300 | 134 (44.7) | 39 (13) | 30 (10) | 59 (19.7) | ||

| Singapore | 27 | DSM-IV, NINDS-AIREN, NINCDS-ADRDS | 50 | 14817 | 5782 | 23,3 | 212 (3.7) | 121 (2.1) | 101 (1.8) | |

| Taiwan | 28 | DSM-III-R | 65 | 1736 | 44 (2.5) | 35 (2.0) | 3 (0.2) | |||

| Taiwan | 29 | ICD10, NINDS-AIREN, NINCDS-ADRDA | 65 | 2915 | 60,6 | 108 (3.7) | 58 (1.98) | 25 (0.9) | 17 (0.6) | |

| Taiwan | 30 | DSM-III | 60 | 2288 | 29 (1.3) | 18 (0.3) | ||||

| Africa | ||||||||||

| Benin, west Africa. | 31 | DSM III, NINDS-ADRDA | 65 | 502 | 96,6 | 13 (2.6) | 11 (2.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Egypt | 32 | DSM-IIIR, NINCDS-ADRDA | 60 | 2000 | 1383 | 92 | 81 (5.9) | 39 (2.8) | 17 (1.2) | 7 (0.5) |

| Nigeria | 33 | ICD-10, DSM-III-R, NINCDS-ADRDA | 65 | 2494 | 100 | 28 (1.1) | 18 (0.7) | 8 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | |

| Latin America | ||||||||||

| Brazil | 34 | DSM-IV | 65 | 2072 | 38,3 | 105 (5.1) | 34 (1.6) | 34 (1.6) | 37 (1.8) | |

| Brazil | 35 | DSM-IV | 65 | 1656 | 34,2 | 118 (7.1) | 65 (3.9) | 11 (0.7) | ||

AD=Alzheimer's disease, VD=Vascular Dementia

We found that the prevalence of AD and MCI increases with age and decreases with school years. Many previous studies found that female gender, illiteracy and age are risk factors for developing dementia [36–38]. Considering the high illiteracy rate in Wadi-Ara, we compared our results to similar studies in other populations with limited education (see Table 5). With the exception of one study in Qatar [26], the prevalence of AD in these other populations (range 0.3–13%) was lower than in Wadi-Ara. In addition, we found that MCI was much more prevalent in Wadi-Ara than in populations in the few studies which measured the rate of MCI (range 4.5–10.4%).

The prevalence of dementia in Arabic speaking countries has indeed rarely been studied. Results from a clinic-based study [26] performed in Qatar are not directly comparable to those from our community-based study, despite the fact that these populations are religiously and culturally similar. The one other study performed in an Arabic population [32] found a lower prevalence of AD than in our study (2.9 % vs. 9.8%).

The high prevalence rates of AD and MCI in Wadi-Ara might be explained by genetic factors. This idea is supported by the observation that more than one-third of AD subjects in Wadi-Ara belong to the same “hamula” (tribal group) [39]. Recently, Sherva et al [40] performed a high-density genomic scan of 124 AD cases and 142 cognitively normal controls from this community and estimated the average inbreeding coefficient to be equivalent to that for a child of half-first cousins. Remarkably, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele which is the genetic risk factor with the highest attributable risk for AD is actually reduced in this community [38]. The low frequency of ApoE4 in this population suggests the presence of yet unidentified genetic risk factors in this particular cohort.

Other studies have shown that the same polymorphisms in the angiotensin-1 converting enzyme (DCP1) and the neuronal sortilin-related receptor (SORL1) genes are associated with AD risk in Wadi-Ara and other outbred Caucasian populations [41, 42]. An early genetic study using microsatellite markers [39] and our recent genome scan [40] suggest that there are other significant genetic factors for AD in yet to be identified in this population. Vascular risk-factors may also explain the high AD risk in Wadi-Ara [9]. However, this idea is not supported by the observation that the prevalence of VD in this community is similar to that reported for other low literacy cohorts (Table 4).

A major strength of this study is the absence of recruitment bias and the low refusal rate and the second phase in which we were able to re-assess MCI patients and the study of an Arabic population. One of the limitations was the inability to verify diagnoses using neuroimaging and autopsy. Also, our results indicate that the use of cognitive screening tests can generate diagnostic bias, in the direction of overdiagnosis of dementia in cognitively normal but illiterate subjects. Comparing MMSE and BCST scores from our subjects with the normal-values according to literacy [8], we found that in the subjects diagnosed as normal, 19 men (6.5%) and 24 women (11.8%) had MMSE below this norm-values. These subjects would still have been classified as demented in the absence of other diagnostic criteria. Diagnoses in this study were established on clinical findings rather than cutoff scores from a cognitive screen. We had limited ability to evaluate the effect of education on risk of MCI and AD in women because most of the women were illiterate.

We observed that the prevalence of AD was almost three times higher in women compared to men. Female gender has been found to be a risk factor for AD in both developed and underdeveloped countries [36, 43, 44]. In agreement with another large study [45], our results suggest that illiteracy does not entirely account for the higher rate of AD in women. We did not find an effect of gender on the conversion from MCI to AD. A study on conversion from MCI to AD in Brasil also found that education separately, besides age and sex, did not influence progression to AD [46]. A recent large study evaluating the incidence of cognitively impaired not demented and the conversion to AD in a population with a mean 12 years of schooling found that men had significantly lower conversion rates [44].

Our annual MCI to AD conversion rate was estimated as 5.7%. While the annual rate of conversion is around 10% in most studies in specialist/clinical settings and this rate is much lower in community setting as ours ranging between 3% to 6.8% [47–49]. We did not observe any reversal of MCI to cognitively normal at follow-up. In large epidemiological studies, one quarter to one third of MCI subjects were classified as cognitively normal at re-testing. [47–49]. The length of follow-up and the age at time of re-examination might partially explain this discrepancy. In addition, some individuals classified as MCI may long have functioned at a mildly impaired level. Since we used a classification based on CDR, cultural factors in the interpretation of CDR might also play a role. Older adults in these villages do not live alone and are being cared for by their families. They live in a protected environment and certain functional limitations may be under/overestimated due to low expectations from the elderly. The etiology of the high prevalence of AD and MCI in our population remains to be elucidated in the context of the interaction between environmental, cultural, genetic and co-morbid factors. MCI is more common than AD. MCI patients represent a group at high risk for AD and as such a potential target for treatments aimed at slowing cognitive decline.

Acknowledgment

Supported by the NIH RO1 AG017173 and Martin Kellner's Research Fund, American Technion Society.

References

- 1.Kalaria RN, Maestre GE, Arizaga R, Friedland RP, Galasko D, Hall K, Luchsinger JA, Ogunniyi A, Perry EK, Potocnik F, Prince M, Stewart R, Wimo A, Zhang ZX, Antuono P World Federation of Neurology Dementia Research Group. Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:812–826. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaber L, Halpern GJ, Shohat T. Trends in the frequencies of consanguineous marriages in the Israeli Arab community. Clin Genet. 2000;58:106–110. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.580203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron-Epel O, Haviv-Messika A, Tamir D, Nitzan-Kaluski D, Green M. Multiethnic differences in smoking in Israel: pooled analysis from three national surveys. Eur J Public Health. 2004;14:384–389. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.4.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowirrat A, Treves TA, Friedland RP, Korczyn AD. Prevalence of Alzheimer's type dementia in an elderly Arab population. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:119–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glik A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Deeb A, Strugatsky R, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R. Essential tremor might be less frequent than Parkinson’s disease in north Israel Arab villages. Mov Disord. 2009;24:119–122. doi: 10.1002/mds.22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inzelberg R, Mazarib A, Masarwa M, Abuful A, Strugatsky R, Friedland RF. Essential tremor prevalence is low in Arabic villages in Israel: door-to-door neurological examinations. J Neurol. 2006;253:1557–1560. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israeli-Korn SD, Massarwa M, Schechtman E, Strugatsky R, Avni S, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with mild parkinsonian signs in a door-to-door study. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2010;22:1005–1013. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israeli-Korn SD, Masarwa M, Schechtman E, Abuful A, Strugatsky R, Avni S, Farrer LA, Friedland RP, Inzelberg R. Hypertension increases the probability of Alzheimer's disease and of mild cognitive impairment in an Arab community in northern Israel. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34:99–105. doi: 10.1159/000264828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies AM. Epidemiology of Senile Dementia in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Brookdale Foundation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inzelberg R, Schechtman E, Abuful A, Masarwa M, Mazarib A, Strugatsky R, Farrer LA, Green RC, Friedland RP. Education effects on cognitive function in a healthy aged Arab population. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19:593–603. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL, Eastwood R, Gauthier S, Tuokko H, McDowell I. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet. 1997;349:1793–1796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The ICD-10. Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou DF, Wu CS, Qi H, Fan JH, Sun XD, Como P, Qiao YL, Zhang L, Kieburtz K. Prevalence of dementia in rural China: impact of age gender and education. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;114:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang ZX, Zahner GE, Román GC, Liu J, Hong Z, Qu QM, Liu XH, Zhang XJ, Zhou B, Wu CB, Tang MN, Hong X, Li H. Dementia subtypes in China: prevalence in Beijing, Xian, Shanghai and Chengdu. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:447–453. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu HF, Lam LC, Chi I, Leung T, Li SW, Law WT, Chung DW, Fung HH, Kan PS, Lum CM, Ng J, Lau J. Prevalence of dementia in Chinese elderly in Hong Kong. Neurology. 1998;50:1002–1009. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang MY, Katzman R, Salmon D, Jin H, Cai GJ, Wang ZY, Qu GY, Grant I, Yu E, Levy P, Klauber MR, Liu WT. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender, and education. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:428–437. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandra V, Ganguli M, Pandav R, Johnston J, Belle S, DeKosky ST. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in rural India. The Indo-US study. Neurology. 1998;51:1000–1008. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajkumar S, Kumar S, Thara R. Prevalence of dementia in a rural setting: A report from India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:702–707. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199707)12:7<702::aid-gps489>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suh GH, Kim JK, Cho MJ. Community study of dementia in the older Korean rural population. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:606–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee DY, Lee JH, Ju YS, Lee KU, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Yoon JC, Ha J, Woo JI. The prevalence of dementia in older people in an urban population of Korea: the Seoul study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1233–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamad AI, Ibrahim MA, Sulaiti EM. Dementia in Qatar. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahadevan S, Saw SM, Gao W, Tan LC, Chin JJ, Hong CY, Venketasubramanian N. Ethnic differences in Singapore's dementia prevalence: the stroke, Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, and dementia in Singapore study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2061–2068. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu HC, Fuh JL, Wang SJ, Liu CY, Larson EB, Lin KN, Wang HC, Chou P, Wu ZA, Lin CH, Wang PN, Teng EL. Prevalence and subtypes of dementia in a rural Chinese population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1998;12:127–134. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199809000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin RT, Lai CL, Tai CT, Liu CK, Yen YY, Howng SL. Prevalence and subtypes of dementia in southern Taiwan: impact of age, sex, education, and urbanization. J Neurol Sci. 1998;160:67–75. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu HC, Lin KN, Teng EL, Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Guo NW, Chou P, Hu HH, Chiang BN. Prevalence and subtypes of dementia in Taiwan: a community survey of 5297 individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:144–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerchet M, Houinato D, Paraiso MN, von Ahsen N, Nubukpo P, Otto M, Clément JP, Preux PM, Dartigues JF. Cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly people living in rural Benin, west Africa. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:34–41. doi: 10.1159/000188661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrag A, Farwiz HM, Khedr EH, Mahfouz RM, Omran SM. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementing disorders: Assiut-Upper Egypt study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9:323–328. doi: 10.1159/000017084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogunniyi A, Gureje O, Baiyewu O, Unverzagt F, Hall KS, Oluwole S, Osuntokun BO, Hendrie HC. Profile of dementia in a Nigerian community-types, pattern of impairment, and severity rating. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997;89:392–396. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scazufca M, Menezes PR, Vallada HP, Crepaldi AL, Pastor-Valero M, Coutinho LM, Di Rienzo VD, Almeida OP. High prevalence of dementia among older adults from poor socioeconomic backgrounds in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:394–405. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrera E, Jr, Caramelli P, Silveira AS, Nitrini R. Epidemiologic survey of dementia in a community-dwelling Brazilian population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16:103–108. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200204000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen K, Launer LJ, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, Kragh-Sorensen P, Baldereschi M, Brayne C, Lobo A, Martinez-Lage JM, Stijnen T, Hofman A. Gender differences in the incidence of AD and vascular dementia: the EURODEM studies. Neurology. 1999;53:1992–1997. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borenstein AR, Copenhaver CI, Mortimer JA. Early-life risk factors for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;2:63–72. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000201854.62116.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowirrat A, Friedland RP, Farrer L, Baldwin C, Korczyn A. Genetic and environmental risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease in Israeli Arabs. J Mol Neurosci. 2002;19:239–245. doi: 10.1007/s12031-002-0040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farrer LA, Bowirrat A, Friedland RP, Waraska K, Korczyn AD, Baldwin CT. Identification of multiple loci for Alzheimer disease in a consanguineous Israeli–Arab community. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:415–422. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherva R, Baldwin CT, Inzelberg R, Vardarajan B, Cupples LA, Lunetta K, Bowirrat A, Naj A, Pericak-Vance MA, Friedland RP, Farrer LA. Identification of novel candidate genes for Alzheimer disease by autozygosity mapping using genome wide SNP data from an Israeli-Arab community. J Alz Dis. 2011;23:349–359. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meng Y, Baldwin CT, Bowirrat A, Waraska K, Inzelberg R, Friedland RP, Farrer LA. Association of polymorphisms in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene and Alzheimer disease in an Israeli-Arab community. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:871–877. doi: 10.1086/503687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogaeva E, Meng Y, Lee JH, Gu Y-J, Zou F, Kawarai T, Katayama T, Baldwin CT, Cheng R, Hasegawa H, Chen F, Shibata N, Lunetta KL, Pardossi-Piquard R, Bohm C, Wakutani Y, Cupples LA, T.Cuenco K, Green RC, Pinessi L, Rainero I, Sorbi S, Bruni A, Duara R, Friedland R, Inzelberg R, Hampe W, Bujo H, Song Y, Andersen O, Graff-Radford N, Petersen R, Dickson D, Der SD, Fraser PE, Schmitt-Ulms G, Younkin S, Mayeux R, Farrer LA, St George-Hyslop P. The sortilin-related receptor SORL1 is functionally and genetically associated with Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:168–177. doi: 10.1038/ng1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S. The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:809–815. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Godinho C, Camozzato AL, Onyszko D, Chaves ML. Estimation of the risk of conversion of mild cognitive impairment of Alzheimer type to Alzheimer’s disease in a south Brazilian population-based elderly cohort: the PALA study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011 Nov 17;:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211002043. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Plassman BL, Langa KM, McCammon RJ, Fisher GG, Potter GG, Burke JR, Steffens DC, Foster NL, Giordani B, Unverzagt FW, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Heeringa SG, Weir DR, Wallace RB. Incidence of dementia and cognitive impairment, not dementia in the United States. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:418–426. doi: 10.1002/ana.22362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Letenneur L, Gilleron V, Commenges D, Helmer C, Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF. Are sex and educational level independent predictors of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease? Incidence data from the PAQUID project. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1999;66:177–183. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruscoli M, Lovestone S. Is MCI really just early dementia? A systematic review of conversion studies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:129–140. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia – meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:252–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganguli M, Snitz BE, Saxton JA, Chang C-CH, Lee C-W, Vander Bilt J, Hughes TF, Loewenstein DA, Unverzagt FW, Petersen RC. Outcomes of mild cognitive impairment by definition. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:761–767. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]