OVERVIEW

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) results from autoimmune attack on the insulin producing pancreatic β-cells. While there is ongoing research to artificially reproduce the critical function of the β-cell with a closed loop system in which glucose sensing is tethered to insulin delivery, an FDA approved clinical product has remained elusive. The definitive cure for T1D is to ensure that the necessary functional β-cell mass remains. As β-cell destruction is immune mediated, many efforts to halt this process have focused on immuno-modulatory and antiinflammatory interventions.

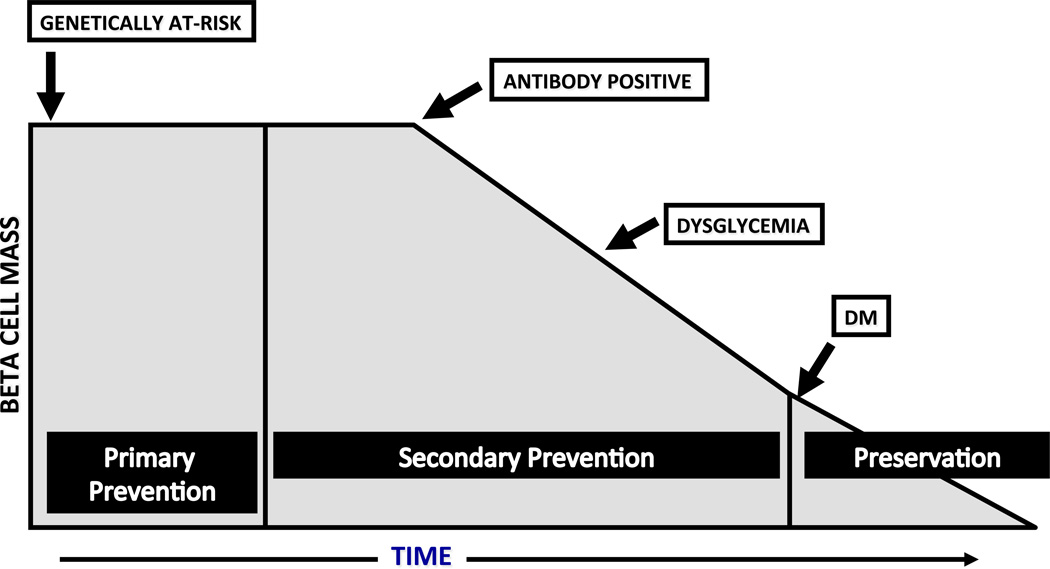

In theory, one could intervene at 3 different points in the course of diabetes to affect a cure: 1) prevention, before the development of diabetes; 2) preservation, after the diagnosis, while some functional β-cell mass still remains; and 3) replacement, for those who have had diabetes for an extended period of time, and who have no residual β-cell function (see Figure 1). Promising efforts are underway at all 3 of these stages. This review will focus on the immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory interventions in the first two stages when there is still some β-cell mass to preserve. However, these efforts may ultimately apply to β-cell replacement, especially when stem cell approaches allow us to develop autologous β-cell replacement, as these cells will remain under autoimmune attack.

Figure 1.

Times of Potential Intervention for T1D trials. The stages of diabetes and times of potential intervention are listed from left to right in the context of hypothetical β-cell mass.

TRIAL CONSIDERATIONS

There are important philosophical issues to consider at each stage of potential intervention. T1D is very different than a life threatening disease such as cancer. Current technology affords a means to live with the disease, although the daily management is imperfect and tedious, and thus, affected individuals remain at risk for acute and chronic complications. Therefore, one must carefully balance the potential risk of any proposed therapy versus possible benefits. Different stages for intervention present different challenges.

Given the relatively low incidence of T1D, trials aimed at preventing disease require screening a large population to find the subset of subjects at risk, enrolling a large enough number of subjects to have a well powered study, and finally, having a long enough follow-up period to determine potential benefit of the intervention. These studies are lengthy and costly. For studies later in the course of disease, such as at the time of diagnosis, there is a defined eligibility group with T1D, and thus, less initial screening. However, intervention at a later time point with limited remaining β-cell mass may require a more aggressive therapy to halt on-going immune destruction.

There are numerous other limitations in the study of T1D. While the primary outcome for prevention trials is usually the development of autoantibodies, impaired glucose tolerance, or progression to T1D, the primary outcome for most new onset TID trials is preservation of β-cell function. To date, we have not identified a surrogate marker for evaluating β-cell function. There is no imaging study that reflects β-cell mass, nor any immunological marker that correlates with preservation of β-cell mass. Therefore, we rely upon a stimulated C-peptide level in response to a mixed meal tolerance test or glucagon in order to estimate functional β-cell mass. Meaningful changes in C-peptide are evaluated over the course of months to years, and thus require a long duration of follow-up to reach the primary outcome. Ideally, we would identify a short term surrogate measure that correlates with long term metabolic effects, but measures such as change in autoantibody status or T-cells have not proven helpful.

Another consideration is the population studied. The incidence of T1D is increasing, particularly in younger children who appear to have a more robust autoimmune process with more rapid progression to disease and a shorter remission (or honeymoon) phase. For safety reasons, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mandates that most new onset studies initially target an older age cohort and thus, many trials are not conducted in the highest risk younger age population. There are suggestions that some studies show possible efficacy in a younger age group that may not be seen in an older cohort, such as with anti-CD3 and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)(1, 2). Thus, if limiting ourselves to smaller initial clinical trials in adults, we may end up discarding possible therapies that could benefit some patients with T1D.

In order to predict the best interventions for clinical trials, one must understand the underlying pathophysiology of T1D. T1D results from a combination of genetic risk and environmental exposures which initiate autoimmune destruction of β-cells. Research efforts have demonstrated that immune dysregulation in patients with T1D is complex and multi-factorial, and these insights have been supported by findings from animal models such as the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse. There are many similarities between the NOD mouse and human TID including loci of genetic susceptibility, the influence of environmental factors, and the breakdown of immune regulation(3). Diabetes in both the NOD mouse and humans results from β-cell destruction via a complex cascade of events: the innate immune response, autoantibody producing B cells and autoreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

It is believed that macrophages and dendritic cells (antigen presenting cells or APCs) are the first cells to enter the pancreas. These cells present self antigen and activate T cells. Over a variable period of time, further β-cell destruction ensues, releasing more self-antigen for presentation by the aforementioned cells as well as B cells. These cells amplify T cell activation, ultimately causing more β-cell destruction and finally, a diagnosis of diabetes. T cells seem to play the most important role in β-cell destruction, and thus many clinical trials to date have utilized agents that affect T cells either directly or indirectly. Further detailed description of this process is beyond the scope of this review, and we refer the reader to more complete recent reviews(4, 5).

Agents considered for clinical trials include those that have efficacy in pre-clinical models of T1D. Over 300 agents have been shown to prevent or cure diabetes in the NOD mouse(6). Many of these successful agents have been given early in the course of disease. However, a more limited number are able to prevent diabetes mellitus (DM) once the autoimmune process is established, and even fewer are effective at reversing disease once DM has started. While the NOD mouse model is certainly useful, not every agent that is effective in the mouse is effective in man and not all therapies can be tested in an animal model (such as humanized mAbs). Therefore, investigators must also draw from clinical experience in alloimmunity, considering drugs that are safe and effective in organ transplantation, as well as agents that offer promise in related autoimmune diseases.

Current immunologic interventions can be sub-divided into several broad categories including: 1) immuno-modulatory or immunosuppressant agents, such as anti-CD3 and CTLA-4 Ig mAbs,; 2) anti-inflammatory agents, such as omega-3 fatty acids and nicotinamide; and 3) antigen-based therapies, such as insulin or glutamate decarboxylase. As more clinical trials have been conducted with immuno-modulatory agents, and these have enjoyed the greatest success to date, this review will focus more extensively on these particular studies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Partial list of past and ongoing, trials in Type 1 diabetes that are referenced in this review.

| INTERVENTION | OUTCOME | STUDY STATUS |

|---|---|---|

| PREVENTION TRIALS | ||

| Cow’s milk protein avoidance (TRIGR) | Pilot, promising | Fully powered trial enrolled, results pending |

| Gluten avoidance | Pilot, inconclusive | |

| Omega 3 fatty acid supplementation (NIP) | Pilot, did not reach primary outcome | |

| Vitamin D supplementation | Pilot, promising | |

| Parenteral insulin (DPT-1) | No Effect | |

| Oral insulin (DPT-1) | Did not reach primary outcome; Promising in subset of subjects | Enrolling confirmatory study |

| Intranasal insulin | Finnish study, no effect | Study enrolling in Australia (INIT II) |

| Nicotinamide (ENDIT) | No Effect | |

| Anti-CD3 mAb | Currently enrolling | |

| CTLA4 Ig | Currently enrolling | |

| PRESERVATION TRIALS | ||

| Anti-CD3 mAb | Series of phase 2 and 3 studies, promising | |

| CTLA-4 Ig | Phase 2, promising | |

| LFA-3 Ig | Phase 2 | Fully enrolled with results pending |

| ATG, cyclophosphamide, G-CSF | Three phase 1 studies, promising efficacy but safety concerns | |

| ATG | Phase 2 | Fully enrolled with results pending |

| G-CSF | Small phase 2 | Fully enrolled with results pending |

| ATG + G-CSF | Small phase 2 | Fully enrolled with results pending |

| IL-2 + Rapamycin | Phase 1, transient decrease in C-peptide | Study discontinued |

| IL-2, low dose | Fully enrolled with results pending | |

| Polyclonal Regulatory T cells | Two phase 1 studies, promising | North American study currently enrolling |

| Umbilical Cord Blood | Phase 1, no effect | |

| Anti-CD20 mAb | Phase 2, promising | |

| Anti-IL-1 mAb | Phase 2, no effect | |

| Anti-IL-1 Receptor | Phase 2, no effect | |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin | Pilot, promising | Phase 2, fully enrolled with results pending |

| GAD-alum vaccine | Phase 2, 3 studies, no effect | |

| Diapep277 vaccine | Phase 2,3 studies, mixed results | |

| Sitagliptin + Lansoprazole | Phase 2 | Fully enrolled with results pending |

| Intense metabolic control | Phase 2 | Fully enrolled with results pending |

PREVENTION

Given that prevention studies require a large number of subjects with a long period of follow-up, they are expensive and time consuming, and thus, they are few. Furthermore, it is important that agents offer promise, yet do not pose significant risk for subjects either by accelerating progression to diabetes and/or by causing toxicity. Thus, prevention trials have most commonly utilized anti-inflammatory or antigen based therapies as opposed to immuno-suppressive agents.

In order to interdict the process of β-cell destruction, one must develop a means to screen and predict those at risk for disease. The ground work has been laid by a series of natural history studies and algorithms validated in trials such as the Diabetes Prevention Trial—Type 1 (DPT-1) and European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT)(7, 8). One helpful means to track this process is the development of β-cell autoantibodies, with higher titer and greater number of such antibodies conferring a progressive increase in T1D risk. As one moves closer to the clinical presentation, metabolic abnormalities become apparent on studies such as intravenous or oral glucose tolerance testing. With this paradigm in mind, one could consider interventions at several different points along the continuum of progression to T1D (see Figure 1). Primary prevention targets those born into a family with an index case of T1D or those with a high risk genotype, but with no evidence yet of autoimmunity. Secondary prevention efforts target those who have some evidence of autoimmunity, i.e. who have developed autoantibodies, but have not yet developed DM. Individuals at this stage can be further sub-divided into intermediate and high risk groups. The intermediate risk group is defined as those with 2 or more autoantibodies but no evidence of metabolic change and are at a 25–50% risk of developing DM in the next 5 years. A higher risk subset are those who not only have autoantibodies but also signs of changes in β-cell function as uncovered on an oral glucose tolerance test, with either impaired fasting glucose, impaired 2 hour glucose, or an intermediate glucose value > 200 mg/dl (referred to as dysglycemia). Subjects with this profile have >50% risk of developing DM in the next 5 years.

Primary Prevention Trials

Because the gut represents the largest interface between exogenous antigens and the immune system, considerable interest lies in evaluating the role of nutrition in early childhood, and how the nature and timing of different exposures modify the risk for developing autoimmunity in the form of T1D later in life. Prior studies in both animals and humans suggest that shorter duration of breast feeding and/or early exposure to cow’s milk increases the risk for β-cell autoimmunity. The Trial to Reduce Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus in the Genetically at Risk (TRIGR) is an on-going prevention study in infants with an HLA allele conferring an increased risk of T1D and who have a 1st degree relative with the disease(9). The pilot study included 203 children and showed that avoidance of foods containing bovine protein in the first 6–8 months of life and supplementation of breast milk with highly hydrolyzed milk formula (Nutramigen) as opposed to a cow’s milk based formula decreased the risk of developing diabetes related autoantibodies by 50%. The mechanism(s) whereby elemental formula may reduce T1D risk is not known, but hypotheses include: reduction in gut permeability to antigens that may cross-react with β-cell autoantigens, induction of protective regulatory T cells in the lymphoid tissue lining the gut, gut microflora modification, or some combination thereof. This study is now fully enrolled with 2160 infants in 15 participating countries and is powered to identify differences in progression to T1D (NCT0017977).

Similar to the TRIGR study, the BABYDIET study examined the impact of timing of nutritional exposure on islet cell autoimmunity. The hypothesis that delaying exposure to dietary gluten reduces the risk of islet cell autoimmunity was supported by mouse models and epidemiologic human data. In this pilot study of 150 infants with a 1st degree relative with TID, delaying gluten exposure until 12 months of age resulted in no reduction in islet autoimmunity(10). However, the study was not powered for efficacy, and compliance was problematic with this open label study design.

Data suggests that inflammation contributes to the development of T1D, and therefore, investigation in the role of anti-inflammatory agents in the prevention of diabetes has been conducted. One such approach is through supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids, as epidemiological studies support the role of this agent in ameliorating autoimmunity. In an analysis of patients in the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study of the Young (DAISY), a longitudinal observational trial of children with increased risk for the development of T1D, higher omega-3 fatty acid intake and a higher percentage of omega-3 fatty acids in the erythrocyte membrane was associated with a decreased risk of developing islet autoantibodies(11). The Nutritional Intervention to Prevent Type 1 Diabetes (NIP) study is an on-going pilot study examining whether supplementation with the omega-3 fatty acid, Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA), introduced late in utero or shortly after birth and continued for the first few years of life can prevent islet autoimmunity, and will provide more information about this subject (NCT00333554).

Vitamin D and its role as an immuno-modulator has been of interest. Based on epidemiological studies, vitamin D deficiency and TID (as well as other autoimmune diseases) seem to be associated. In an analysis from a Norwegian study, vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy increased the offspring’s risk of developing TID while supplementing with vitamin D during pregnancy was associated with a 50% decrease in the rate of autoantibody development in the offspring (12, 13). A Finnish study noted that supplementing vitamin D in the first year of life was associated with a decreased risk of developing T1D(14). Because of these promising results, vitamin D will continue to be studied at different time points in the disease process, and possibly in combination with other agents.

Secondary Prevention Trials

For those with 2 or more autoantibodies, with or without evidence of β-cell dysfunction, somewhat more aggressive interventions have been utilized in an attempt to prevent progression to DM. One tactic that has been studied is antigen based therapies. There are several well characterized self-antigens in T1D, and these are logical candidates in prevention trials. Insulin has attracted a great deal of interest as it is often the first autoantigen recognized by the immune system in the NOD mouse and in man.

The Diabetes Prevention Trial-1 (DPT-1) was a randomized, controlled, non-blinded North American study to determine if exposure to insulin prior to the onset of T1D would prevent or delay progression to overt disease(7, 15). This trial was based on findings in the NOD mouse and early pilot studies in humans suggesting that exogenous insulin could alter the course of disease. The trial was sub-divided into 2 arms: a high risk group (> 50% chance of developing T1D in next 5 years defined by the presence of > 1 autoantibody and altered glucose metabolism), which received subcutaneous insulin and 4 days of intravenous insulin annually, and an intermediate risk group (25–50% risk of developing DM in 5 years defined by the presence of >1 autoantibody without altered glucose metabolism), which was randomized to either oral insulin or placebo. Parenteral insulin had no effect on preventing T1D(7). Oral insulin did not delay diagnosis in the primary analysis(15). However, in a post-hoc analysis, subjects receiving oral insulin who had higher baseline insulin autoantibody titers appeared to have a statistically significant delay in the onset of T1D by 4.5 years. Furthermore, the rate of progression seemed to increase when antigen exposure was stopped, indicating that the therapy was likely efficacious but required on-going therapy(16). This study has prompted a larger follow-up study with oral insulin to see if such findings are reproducible (NCT00419562).

Insulin therapy has also been explored in a secondary prevention trial when introduced intranasally, but was unsuccessful in meeting the primary endpoint (17). Further attempts are underway in Australia in the Intranasal Insulin Trial II (INIT II) (NCT00336674). Finally, insulin may need to be introduced earlier, and thus, a primary prevention trial with oral insulin at varying doses has been launched(18). Other forms of insulin antigen therapy and other autoantigens will undoubtedly be assessed in future prevention trials.

Anti-inflammatory agents have also been explored at this stage of T1D risk. Based on animal data and small pilot studies, the European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) evaluated the effects of nicotinamide, a free radical scavenger, in the prevention of disease in people with autoantibodies as well as a 1st degree relative with TID. There was no difference in the percentage of people who progressed to T1D between the placebo and treatment groups, perhaps due to the dose being too low or administered too late in the disease process(8).

Finally, the hypothesis that earlier intervention may result in greater efficacy has prompted the study of some immuno-modifying interventions used in new onset T1D as prevention agents. A mAb directed against the CD3 portion of the T-cell receptor that affects T cell signaling is now being studied in the highest-risk members of the prevention group (multiple autoantibodies and dysglycemia), which is considered to be one step upstream of T1D (NCT01030861). A CTLA-4 Ig prevention trial has been launched for similar reasons.

TRIALS IN NEW ONSET TYPE 1 DIABETES

At the time of T1D diagnosis, it has been estimated that 15–40% of β-cell function remains. This remnant can serve one well while it lasts, as evidenced by better overall glycemic control during this remission or “honeymoon” phase of diabetes, with lower hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels and less glycemic variability. There is also evidence from the DCCT that maintaining β-cell function over time decreases the rate of long term complications and severe hypoglycemic events(19). For several decades, investigators have attempted to define safe and effective means to preserve β-cell function following diagnosis. However, intervening so late in the process poses the challenge of being aggressive enough to arrest further destruction while maintaining appropriate safety. A number of agents with different targets have been used with varying levels of success, and a subset of these studies are reviewed herein, with focus on the more promising approaches and the larger, well powered trials with control groups.

Immuno-modulatory Trials

The efficacy of immunosuppression on halting β-cell destruction was established in the 1980s and 1990s with the use of cyclosporine. Cyclosporine is a generalized immunosuppressant, but is particularly effective at suppressing T cell dependent mechanisms. While cyclosporine preserved β-cell function in subjects with recent onset of T1D, there were risks associated with its use: in addition to potential hepato- and nephrotoxicity, not all treated subjects responded, and for those that did respond, continuous therapy, and thus continuous immunosuppression, was required(20). Therefore, while cyclosporine set the stage for using immuno-modulating agents in T1D, it is no longer used due to its relative risk.

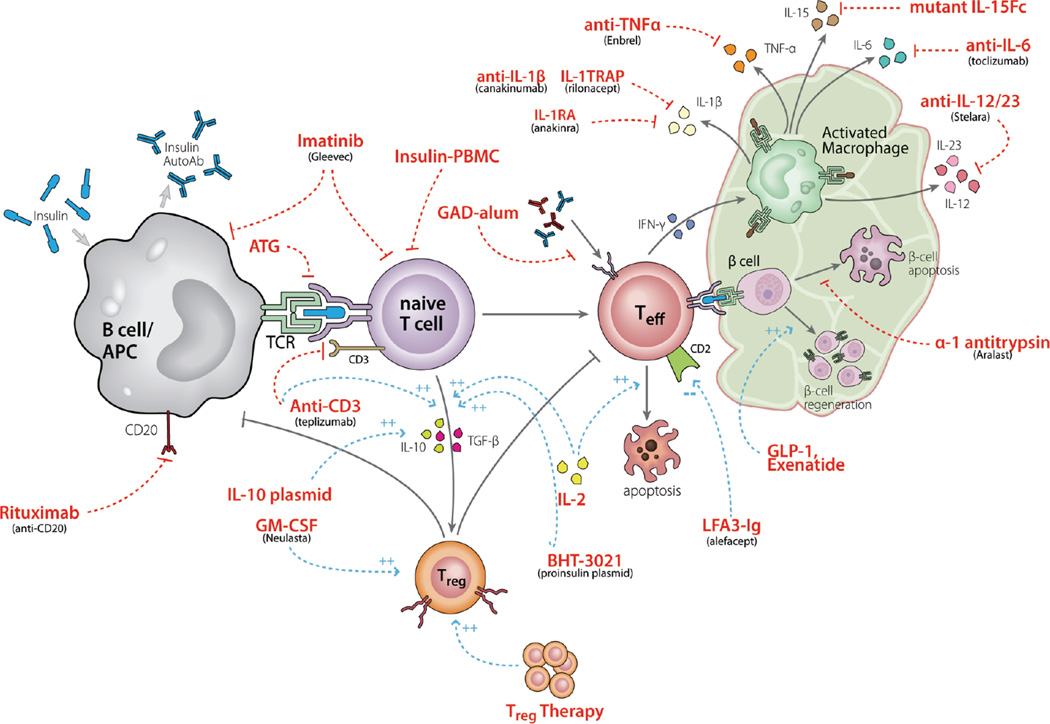

The field remained relatively quiescent until alternate promising therapies became available. One approach has been to more selectively target T cell activation. In order for T cells to become fully activated, they need at least two signals from antigen presenting cells (APCs): an interaction between antigen bound to a MHC molecule on the APC and the T cell receptor (TCR) on the T cell, and an interaction between CD80 and 86 on the APC and CD28 on the T cell, a co-stimulatory signal (see Figure 2). Investigators have utilized a monoclonal antibody (mAb) that targets the CD3-ε epitope of the TCR, altering downstream signaling following interaction between a TCR and APC. This approach exhibited remarkable findings in the NOD mouse, where a short course of anti-CD3 mAb induced a lasting remission in mice with new onset diabetes. Two humanized anti-CD3 mAbs, teplizumab and otelixizumab, have since been developed for clinical use, and both demonstrate efficacy in maintaining β-cell function. The original study showed that a single 14 day course of teplizumab given within 6 weeks of diagnosis preserved B-cell function at 12 months in 75% of treated patients versus only 8% of controls (21). Long term follow up demonstrated a decline in β-cell function after 12 months in the treated group, but a persistent difference from control subjects was noted at 24 months, and extended for up to 5 years(22, 23). Similarly, a single 6 day course of otelixizumab preserved β-cell function in the treated group at 18 months, with differences persisting at 4 years(24, 25). These drugs are fairly well tolerated. Side effects from teplizumab include a flu-like reaction and skin rash in ~50% of patients, and a small percentage of subjects had cytokine release syndrome necessitating early drug termination. Otelixizumab has been associated with somewhat more marked side effects, including reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus. The degree of success with minimal risk associated with these interventions has galvanized the field and spawned a series of downstream trials with these drugs.

Figure 2.

Overview of the pathogenesis of T1D and targets for potential intervention. This figure highlights pathways known to be involved in the pathogenesis of T1D and the numerous potential targets for intervention, some of which are discussed in this review. A key area of focus is on the antigen presenting cell – T cell interaction, where interventions aim to decrease effector T cell activation and increase regulatory T cell generation. Source: Matthews JB, Staeva TP, Bernstein PL, Peakman M, von Herrath M, Group I-JTDCTA. Developing combination immunotherapies for type 1 diabetes: recommendations from the ITN-JDRF Type 1 Diabetes Combination Therapy Assessment Group. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160(2):176–84.

Different dosing strategies of teplizumab, including the timing of intervention and dose strength have been evaluated. The phase II AbATE trial tested the efficacy of adding a second dose of teplizumab at 12 months in an attempt to extend the effects (Herold et al, Diabetes, in print). This trial met its primary endpoint of preserving β-cell function at 24 months relative to the control group. Interestingly, in a post-hoc analysis, patients could be divided into 2 distinct groups: 45% of the treated subjects were considered responders with virtually no change in C-peptide at 24 months, whereas the remaining 55% were non-responders, and not distinguishable from controls. Ideally, one would be able to predict who is likely to respond, and target that group for this agent. Analysis suggests that responders had fewer Th1 T cells at baseline, as well as lower HbA1c levels and exogenous insulin requirements. They were also less likely to develop neutralizing antibodies to the drug.

The Protégé trial was a phase 3, industry sponsored, placebo controlled clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of teplizumab given soon after diagnosis and again 6 months later(2). This trial did not reach statistical significance for the primary outcome, a composite of the percentage of patients with insulin use < 0.5 u/kg/day and HbA1c < 6.5% at 1 year. However, there was less median decline in stimulated C-peptide values between baseline and 1 year in the treatment group, particularly in children ages 8 – 11, patients treated in the United States, and those treated within 6 weeks of diagnosis. Arms of the Protégé trial and DEFEND trial also investigated lower doses of teplizumab and otelixizumab, respectively, and found that the doses given in the original trials were most effective (GlaxoSmithKline press release)(2). Additional phase 3 studies with one or both agents may be conducted to further evaluate their role in new onset T1D. Herold et al have also evaluated the window of opportunity for administration of this therapy, and note that treating subjects from 4–12 months from diagnosis still preserves β-cell function, although not to the degree noted in these earlier onset studies(26). As mentioned previously, these promising results in new-onset subjects have prompted a prevention trial with teplizumab in high risk patients.

Another molecule targeting T cell signaling which has seen moderate success is CTLA-4 Ig. CTLA-4 Ig binds CD80 and 86, blocking interaction with CD28 on the T cell and therefore, the co-stimulatory signal required for T cell activation, proliferation and survival. A phase 2, double blinded, randomized, placebo controlled trial showed that 24 months of CTLA-4 Ig (Abatacept) in patients with new onset T1D conferred a 9.6 month delay in β-cell decline in the treated versus control group(27). Patients followed out to 36 months showed a parallel loss in stimulated C-peptide in the treatment and placebo groups after the initial delay, indicating that CTLA-4 blockade transiently alters the course of disease, but does not change the underlying pathophysiology that causes disease. Offering this drug earlier in the disease process or in combination with a drug with a different target may improve efficacy. A related on-going trial utilizing co-stimulatory blockade with LFA3 Ig (Alefacept) may more selectively target autoreactive T effector memory cells (NCT 00965458).

With the moderate success with a mAb approach, investigators postulated that a polyclonal approach against T cells may have even greater efficacy. In fact, the most successful intervention to date in new onset T1D has come from a combination therapy conducted by Couri et al in an attempt to immunologically “reboot” the immune system with an autologous nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplant(28). In this phase I trial, patients with new onset T1D were treated with cyclophosphamide, followed by G-CSF to mobilize peripheral hematopoietic CD34+stem cells, which were apheresed and stored. The subjects were allowed to recover, then returned for treatment with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclophosphamide, followed by an infusion of their previously harvested progenitor cells. The metabolic effects were striking: twenty of 23 subjects were able to discontinue insulin, 12 for a mean of 31 months, and some for over 4 years. From a safety perspective, subjects remained hospitalized in a bone marrow transplant unit for a mean of 21 days, and side effects included infusion reactions, with some reports of testicular dysfunction and opportunistic infection. While the metabolic effects of this trial are impressive, many are concerned that the associated risks do not justify this approach. Investigators are now “de-constructing” this cocktail, with phase 2 recent onset T1D trials evaluating ATG alone (NCT00515099), G-CSF alone (NCT00662519), and ATG plus G-CSF (NCT01106157) to determine if an equally efficacious but safer cocktail is attainable.

Many of these clinical trials perform mechanistic studies to investigate what alterations in the immune system may be responsible for clinically meaningful outcomes. Mechanistic studies from interventions in animal models and clinical studies imply that many of these therapies not only deplete or blunt T effector cell responses, but also foster the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs), a T-cell subset that serves to suppress autoreactive T cells. The cytokine interleukin-2 (IL-2) is a critical factor in Treg development and maintenance. There is a dose response to IL-2, with low doses selectively augmenting Tregs, but high doses non-specifically activating T cells as well as other immune cells.

Low dose IL-2 has proven effective in graft versus host disease and Hepatitis C related vasculitis(29, 30). An initial attempt to use IL-2 in T1D was a phase 1 trial with 1 month of low dose IL-2 plus 3 months of rapamycin(31). Rapamycin was added to keep autoreactive effector T cells in check while Tregs expanded in response to IL-2. Tregs did indeed expand, but NK cells and eosinophils did as well, and the trial was terminated early because β-cell function transiently declined in all 9 treated patients at 3 months. It is notable that the β-cell function subsequently stabilized. The cause for this decline is not clear, but may be related to the dosing or timing of rapamycin or IL-2, or the combination. A study led by Klatzmann is comparing a lower dose of IL-2 alone versus placebo in T1D and will shed more light on this potential approach (NCT01353833). Investigators are also considering alternate means to more selectively amplify Tregs via this axis. For example, there may be mutated forms of IL-2 that selectively target Tregs and do not induce expansion of other cell types.

Cell Therapy

As a means to bypass all the potential issues noted above, one could consider direct therapy with Tregs. Proof of principle has once again come from studies in the NOD mouse, where purified and in vitro expanded Tregs given to mice with recent onset DM induce a lasting remission. Putnam et al subsequently developed a procedure for purifying and expanding a polyclonal Treg population for clinical use, setting the stage for a currently enrolling phase 1 dose escalation trial with autologous expanded Tregs (NCT01210664)(32). A Polish group recently published results on 10 children infused with a relatively small number of autologous Tregs prepared according to this same protocol, with preservation of stimulated C-peptide at 4 months and no serious adverse events(33). Results from the North American trial are expected in 2014.

Umbilical cord blood may be another source of Tregs. Haller et al conducted a phase 1 trial using umbilical cord blood in children with new onset T1D(34). As expected, the infusions were well tolerated, but did not appear to delay the rate of β-cell decline, likely because not enough Tregs were infused. Further research on umbilical cord blood is ongoing. Ultimately, investigators hope to develop tolerizing antigen specific Tregs for use as a clinical therapy, but such a product is not available at this time.

Another form of cell therapy is infusing altered APCs. Giannoukakis et al modified dendritic cells by treating the cells with modified oligonucleotides targeting co-stimulatory molecules(35). They hypothesize that the modified APCs will be immunosuppressive and alter T cell signaling. A phase I trial showed that treatment with modified dendritic cells is safe, but a larger phase II study is needed to verify the efficacy of this approach.

Targeting B cells

While the majority of interventions have focused on altering T cell signaling, there is also evidence that depleting B cells with the anti-CD20 mAb, rituximab, can help maintain β-cell function in those with new onset T1D(1). This double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial with a single course of drug met its primary endpoint with a higher stimulated C-peptide at 1 year in the treatment group, with a mean delay of C-peptide decline of 8.2 months. However, like the CTLA-4 Ig study, after the initial delay, the rate of decline of C-peptide was the same in the treatment and control groups. Repeated dosing, as is done in other autoimmune diseases, may result in prolonged efficacy, but there may be infectious disease risks from chronic B cell depletion.

Anti-Inflammatory Agents

β-cell destruction may be augmented by inflammation, and thus, another approach to preserving β-cell function is through use of anti-inflammatory agents. IL-1 has been implicated as a primary proinflammatory cytokine and mediator of β-cell destruction. Two recent phase 2 trials evaluated antagonism of the IL-1 axis in recent onset T1D, utilizing the anti-IL1 mAb canakinumab and the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (41). Although well tolerated, neither approach achieved the primary outcome, perhaps because this intervention occurred too late in the autoimmune process. Furthermore, preclinical studies suggest that using an anti-IL-1 mAb synergistically with another agent may preserve β-cell function more effectively than using it alone. Other anti-inflammatory agents with promise in early phase I trials are under investigation, including alpha-1 antitrypsin (NCT 01183468).

Antigen-Based Therapies

When used in new onset T1D, antigen-based therapies have generally proven disappointing to date. Insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), and heat shock protein 60 (hsp60) have been used in a series of clinical trials. While NOD studies and smaller early clinical trials showed promise with the GAD-alum vaccine, a phase 2 trial and an industry sponsored phase 3 trial did not show effects on the rate of β-cell decline compared to placebo groups(36, 37).

Diapep277, an epitope of heat shock protein 60, prevents DM in the NOD mouse, and has since been evaluated in a series of clinical trials. The data from these new onset trials has shown variable results, with preservation of C-peptide in adults in the treated group at 1 year but no effect in children(38, 39). A larger phase 3 trial in new onset adult subjects was just completed and showed a statistically significant difference between the Diapep277 and placebo groups in stimulated C-peptide values from a glucagon stimulated test but not a mixed meal tolerance test at 2 years (Raz et al, unpublished observations). Future clinical trials will need to corroborate these findings and to determine if the statistically significant findings have clinical significance.

Other Approaches

The approaches mentioned to date address means to abrogate autoimmune destruction of β-cells. However, therapies to enhance β-cell repair, regeneration, or neogenesis may also be an important synergistic approach. Animal models suggest that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DDP-IV) inhibitors have salutary effects. An ongoing new onset T1D clinical trial with sitagliptin (DPP-IV inhibitor) and lansoprazole (proton pump inhibitor) will test this hypothesis (NCT01155284). Other studies with related agents are also being considered for prevention and new-onset trials. Growth factors that have been evaluated in animal models and considered for clinical trials include insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and islet neogenesis-associated peptide. Investigators are also exploring the effects of more intensive metabolic control with the use of a continuous glucose sensor and insulin pump in a new onset T1D trial to determine if this non-immunological intervention will preserve β-cell mass (NCT00891995).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS AND CONSIDERATIONS

The trials conducted to date have laid important groundwork for the next generation of studies. Each study had compelling preclinical or related clinical rationale, yet there is on-going concern about what most consider lukewarm results to date. In the vast majority of subjects, no single agent or trial has safely and effectively restored β-cell function for an extended period of time without the need for exogenous insulin therapy.

The last few decades have taught us that the immunological defects of T1D are complex and not completely understood: elucidation of the underlying pathophysiology may guide more rational trials. Insights will continue to be gained from T1D animal models such as the NOD mouse, but, at best, these models will have limitations. The mouse cannot capture the heterogeneity encountered in clinical medicine. Humanizing the mouse immune system, in which the mouse immune system is essentially replaced with human components, may help recapitulate the human derangements of the immune system in a mouse model. Nevertheless, there is no substitute for trying to gain further information directly from humans. Ideally, one would utilize clinical samples. However, very real limitations are posed by the inability to gain direct access to the pancreas and pancreatic lymph nodes. Investigators typically rely on peripheral blood samples where the autoreactive T cell repertoire is present at very low numbers and the inflammatory milieu may not be representative of the affected tissue. Much may be learned from the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donation (nPOD), an organized network collecting and archiving pancreata and other tissues from recently deceased individuals with T1D for further study (www.jdrfnpod.org).

The approach to prevention and new onset T1D clinical trials may now need to be re-evaluated. Most recent trials have been moderate sized phase 2 studies, evaluating a single agent at a single dose, compared to a placebo control group. The number of potential agents in the pipeline continues to steadily expand (see Figure 2), and such an approach is an inefficient means to evaluate and identify the most promising candidates. Thus, study design may need to be refocused on testing a series of agents at varying doses, while utilizing a common control group. In addition, we may need to revisit the primary end point for these trials. The field may benefit from a paradigm shift in study design, such that smaller shorter trials are conducted to obtain some initial sense of efficacy prior to undertaking a fully powered effort. Prevention trials could utilize surrogate measures, such as changes in metabolic or immunologic parameters as an endpoint, rather than T1D. Current new onset studies rely on change in β-cell function over time, often a 12–24 month period, which is an indirect measure of the inciting autoimmune response. Where possible, these studies may benefit from using immune markers that correspond to β-cell destruction as an endpoint, allowing a faster readout of promising agents that should be further evaluated.

Many now feel that the most successful approaches will require targeting more than one pathway in order to interdict this complex process of autoimmune destruction, much as has been necessary with organ transplantation and cancer therapy. Some monotherapies may be able to achieve this: ATG cross-reacts with multiple T cell surface antigens, and may have effects on other cell types; another example is imatinib, an inhibitor of a variety of tyrosine kinases in multiple cell types, which will soon be evaluated in a phase 2 new onset T1D trial. In other cases, combination therapy may be required. Such an approach is easier said than done, as one needs to determine a variety of issues including establishing the best drug combinations with minimal toxicity, the ideal dose and length of therapy for each component of the cocktail, and convincing industry and FDA to embrace such an approach. Some initial guidelines for combination therapies have been offered from an ITN-JDRF assessment group(40). One example of an intriguing combination might be an immune-modulatory agent, such as an anti-CD3 mAb coupled with a drug that may enhance β-cell repair or regeneration, such as GLP-1 agonists or DPP-IV inhibitors. As the list of completed clinical trials with a single agent in new-onset T1D grows, many promising potential combinations will no doubt emerge.

CONCLUSIONS

The vast majority of patients with T1D are not able to consistently meet necessary glycemic targets, and thus remain at risk for acute and long-term complications. Investigators are now able to screen and identify those at risk for T1D, and a series of primary and secondary prevention trials offer promise for blocking progression to overt disease. For those with recent-onset T1D, several immuno-modulatory agents have been found to delay β-cell destruction, and a series of intriguing trials are underway or are being planned. Ultimately, combination therapy, using complementary and synergistic agents, may be necessary to interdict the autoimmune process. New strategies are needed to more efficiently evaluate the emerging pipeline of therapies for both T1D prevention and β-cell preservation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Hilary Thomas is supported by the NIH grant 5T32DK007418.

Contributor Information

Hilary R. Thomas, Department of Medicine and Diabetes Center, University of California, San Francisco, HSW 1102, 513 Parnassus Ave, San Francisco, CA 94143, 415-514-2110 (t), 415-564-5813 (f), hilary.thomas@ucsf.edu.

Stephen E. Gitelman, Department of Pediatrics and Diabetes Center, University of California San Francisco, Box 0434, Rm S-679, 513 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94143, Tel 415.476.3748, Fax 415.476.8214, sgitelma@peds.ucsf.edu.

References

- 1.Pescovitz MD, Greenbaum CJ, Krause-Steinrauf H, Becker DJ, Gitelman SE, Goland R, et al. Rituximab, B-lymphocyte depletion, and preservation of beta-cell function. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(22):2143–2152. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sherry N, Hagopian W, Ludvigsson J, Jain SM, Wahlen J, Ferry RJ, Jr, et al. Teplizumab for treatment of type 1 diabetes (Protege study): 1-year results from a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9790):487–497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60931-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bluestone JA, Herold K, Eisenbarth G. Genetics, pathogenesis and clinical interventions in type 1 diabetes. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1293–1300. doi: 10.1038/nature08933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeker LT, Bour-Jordan H, Bluestone JA. Breakdown in peripheral tolerance in type 1 diabetes in mice and humans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(3):a007807. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowe PA, Campbell-Thompson ML, Schatz DA, Atkinson MA. The pancreas in human type 1 diabetes. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33(1):29–43. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0208-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shoda LK, Young DL, Ramanujan S, Whiting CC, Atkinson MA, Bluestone JA, et al. A comprehensive review of interventions in the NOD mouse and implications for translation. Immunity. 2005;23(2):115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diabetes Prevention Trial--Type 1 Diabetes Study G. Effects of insulin in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(22):1685–1691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gale EA, Bingley PJ, Emmett CL, Collier T European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial G. European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT): a randomised controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363(9413):925–931. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15786-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knip M, Virtanen SM, Seppa K, Ilonen J, Savilahti E, Vaarala O, et al. Dietary intervention in infancy and later signs of beta-cell autoimmunity. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1900–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hummel S, Pfluger M, Hummel M, Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG. Primary dietary intervention study to reduce the risk of islet autoimmunity in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes: the BABYDIET study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(6):1301–1305. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris JM, Yin X, Lamb MM, Barriga K, Seifert J, Hoffman M, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake and islet autoimmunity in children at increased risk for type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2007;298(12):1420–1428. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.12.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorensen IM, Joner G, Jenum PA, Eskild A, Torjesen PA, Stene LC. Maternal serum levels of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Diabetes. 2012;61(1):175–178. doi: 10.2337/db11-0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fronczak CM, Baron AE, Chase HP, Ross C, Brady HL, Hoffman M, et al. In utero dietary exposures and risk of islet autoimmunity in children. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3237–3242. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hypponen E, Laara E, Reunanen A, Jarvelin MR, Virtanen SM. Intake of vitamin D and risk of type 1 diabetes: a birth-cohort study. Lancet. 2001;358(9292):1500–1503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skyler JS, Krischer JP, Wolfsdorf J, Cowie C, Palmer JP, Greenbaum C, et al. Effects of oral insulin in relatives of patients with type 1 diabetes: The Diabetes Prevention Trial--Type 1. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(5):1068–1076. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vehik K, Cuthbertson D, Ruhlig H, Schatz DA, Peakman M, Krischer JP, et al. Long-term outcome of individuals treated with oral insulin: diabetes prevention trial-type 1 (DPT-1) oral insulin trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1585–1590. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanto-Salonen K, Kupila A, Simell S, Siljander H, Salonsaari T, Hekkala A, et al. Nasal insulin to prevent type 1 diabetes in children with HLA genotypes and autoantibodies conferring increased risk of disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1746–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achenbach P, Bonifacio E, Williams AJ, Ziegler AG, Gale EA, Bingley PJ, et al. Autoantibodies to IA-2beta improve diabetes risk assessment in high-risk relatives. Diabetologia. 2008;51(3):488–492. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0912-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steffes MW, Sibley S, Jackson M, Thomas W. Beta-cell function and the development of diabetes-related complications in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):832–836. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bougneres PF, Carel JC, Castano L, Boitard C, Gardin JP, Landais P, et al. Factors associated with early remission of type I diabetes in children treated with cyclosporine. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(11):663–670. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803173181103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herold KC, Hagopian W, Auger JA, Poumian-Ruiz E, Taylor L, Donaldson D, et al. Anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody in new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(22):1692–1698. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herold KC, Gitelman S, Greenbaum C, Puck J, Hagopian W, Gottlieb P, et al. Treatment of patients with new onset Type 1 diabetes with a single course of anti-CD3 mAb Teplizumab preserves insulin production for up to 5 years. Clin Immunol. 2009;132(2):166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herold KC, Gitelman SE, Masharani U, Hagopian W, Bisikirska B, Donaldson D, et al. A single course of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody hOKT3gamma1(Ala-Ala) results in improvement in C-peptide responses and clinical parameters for at least 2 years after onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(6):1763–1769. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keymeulen B, Vandemeulebroucke E, Ziegler AG, Mathieu C, Kaufman L, Hale G, et al. Insulin needs after CD3-antibody therapy in new-onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(25):2598–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keymeulen B, Walter M, Mathieu C, Kaufman L, Gorus F, Hilbrands R, et al. Four-year metabolic outcome of a randomised controlled CD3-antibody trial in recent-onset type 1 diabetic patients depends on their age and baseline residual beta cell mass. Diabetologia. 2010;53(4):614–623. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1644-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herold KC, Gitelman SE, Willi SM, Gottlieb PA, Waldron-Lynch F, Devine L, et al. Teplizumab treatment may improve C-peptide responses in participants with type 1 diabetes after the new-onset period: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2013;56(2):391–400. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2753-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orban T, Bundy B, Becker DJ, DiMeglio LA, Gitelman SE, Goland R, et al. Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):412–419. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60886-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Couri CE, Oliveira MC, Stracieri AB, Moraes DA, Pieroni F, Barros GM, et al. C-peptide levels and insulin independence following autologous nonmyeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2009;301(15):1573–1579. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koreth J, Matsuoka K, Kim HT, McDonough SM, Bindra B, Alyea EP, 3rd, et al. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saadoun D, Rosenzwajg M, Joly F, Six A, Carrat F, Thibault V, et al. Regulatory T-cell responses to low-dose interleukin-2 in HCV-induced vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2067–2077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long SA, Rieck M, Sanda S, Bollyky JB, Samuels PL, Goland R, et al. Rapamycin/IL-2 combination therapy in patients with type1 diabetes augments Tregs yet transiently impairs beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2012;61(9):2340–2348. doi: 10.2337/db12-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Putnam AL, Brusko TM, Lee MR, Liu W, Szot GL, Ghosh T, et al. Expansion of human regulatory T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2009;58(3):652–662. doi: 10.2337/db08-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marek-Trzonkowska N, Mysliwiec M, Dobyszuk A, Grabowska M, Techmanska I, Juscinska J, et al. Administration of CD4+CD25highCD127-regulatory T cells preserves beta-cell function in type 1 diabetes in children. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(9):1817–1820. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haller MJ, Wasserfall CH, Hulme MA, Cintron M, Brusko TM, McGrail KM, et al. Autologous umbilical cord blood transfusion in young children with type 1 diabetes fails to preserve C-peptide. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(12):2567–2569. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giannoukakis N, Phillips B, Finegold D, Harnaha J, Trucco M. Phase I (safety) study of autologous tolerogenic dendritic cells in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):2026–2032. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wherrett DK, Bundy B, Becker DJ, DiMeglio LA, Gitelman SE, Goland R, et al. Antigen-based therapy with glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) vaccine in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9788):319–327. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60895-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ludvigsson J, Krisky D, Casas R, Battelino T, Castano L, Greening J, et al. GAD65 antigen therapy in recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):433–442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lazar L, Ofan R, Weintrob N, Avron A, Tamir M, Elias D, et al. Heat-shock protein peptide DiaPep277 treatment in children with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind phase II study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23(4):286–291. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raz I, Avron A, Tamir M, Metzger M, Symer L, Eldor R, et al. Treatment of new-onset type 1 diabetes with peptide DiaPep277 is safe and associated with preserved beta-cell function: extension of a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23(4):292–298. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews JB, Staeva TP, Bernstein PL, Peakman M, von Herrath M Group I-JTDCTA. Developing combination immunotherapies for type 1 diabetes: recommendations from the ITN-JDRF Type 1 Diabetes Combination Therapy Assessment Group. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160(2):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moran A, Bundy B, Becker DJ, Dimeglio LA, Gitelman SE, Goland R, et al. Interleukin-1 antagonism in type 1 diabetes of recent onset: two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60023-9. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]