Abstract

Although conversion of an osteochondroma to chondrosarcoma is a well-described rare occurrence, it is usually associated with syndromes such as multiple hereditary exostoses and is much more common after maturity. We present here a rare case of secondary pelvic chondrosarcoma arising from a solitary exostosis in a pediatric patient. An 11-year-old, otherwise healthy, female was referred to our clinic for evaluation of a pelvic mass detected on a radiograph. The radiographs obtained by the referring physician demonstrated a large lesion arising from the right superior pubic ramus, which was visible but not identified on an abdominal radiograph several years prior. Histopathologic analysis showed chondrosarcoma which was supported by an additional opinion to rule out chondroblastic osteosarcoma. The patient was treated with wide resection without adjuvant therapy and is doing well with no evidence of recurrence five years post-operatively. There have been only a few small case series describing chondrosarcoma in the pediatric patient. Even rarer are descriptions of secondary chondrosarcoma with only occasional cases reported as part of larger case series. Chondrosarcoma is a rare and difficult diagnosis in the pediatric patient. There is often considerable debate between chondrosarcoma and chondroblastic osteosarcoma, and the treatment implications of differentiating these diagnoses are of paramount importance.

Introduction

Although a relatively common primary malignant tumor of bone in the adult population, it is exceedingly rare for a chondrosarcoma to affect a pediatric patient1, and to our knowledge there are only a few small series reported in the literature2–5.

Conversion of an osteochondroma to chondrosarcoma is a well-described, albeit rare, occurrence. The conversion typically results in a low-grade chondrosarcoma, although higher grade tumors are also possible. It is usually associated with syndromes such as multiple hereditary exostoses (MHE) and is far more common after maturity, with only occasional reports of this occurring in the pediatric patient1,6. The purpose of this report is to present a rare case of secondary pelvic chondrosarcoma in a pediatric patient. The patient and her family were informed of our intention to submit de-identified case information for publication, and verbal consent was obtained.

We aim to highlight the characteristics of the tumor and the issues and implications associated with making this difficult diagnosis in this age group.

Case Report

An 11-year-old otherwise healthy female presented to our office for evaluation of a pelvic mass. She had symptoms including a limp and activity-related pain in the right groin for one month. On examination there was a firm, fixed mass in the right groin.

Radiographs demonstrated a large lesion arising from the right superior pubic ramus (Figure 1). An abdominal radiograph (Figure 2) obtained four years prior for an evaluation of abdominal pain, although read as negative, clearly demonstrates an abnormal lesion in the same location. The lesion is not entirely visualized such that comparisons of a size differential across the four year time span are not possible. We obtained a plain radiographic skeletal survey to evaluate for other potential osteochondromatous lesions. This study was unremarkable, essentially ruling out the diagnosis of MHE.

Figure 1. An anteroposterior pelvis radiograph at the time of presentation demonstrates the lesion arise from the right pubis.

Figure 2. Abdominal radiograph obtained four years prior to onset of complaints.

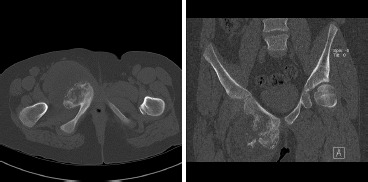

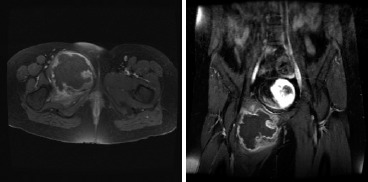

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the pelvis were obtained (Figures 3 and 4). The imaging of the pelvis demonstrated a large lesion arising from the superior pubic ramus with a large associated soft-tissue mass. The soft tissue component showed stippled areas of calcification on the CT scan and a high signal on T2 weighted imaging throughout the mass on MRI with peripheral enhancement on the T1 post-contrast films. The radiographic differential diagnosis favored chondrosarcoma; however, also included were chondroblastic osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma. Staging studies demonstrated no evidence of pulmonary metastatic lesions and no other bony lesions.

Figure 3. (a) Axial and (b) coronal CT scan representative images of the lesion.

Figure 4. (a) Axial and (b) coronal T1 fat-saturation (post-gadolineum) MRI images of the lesion.

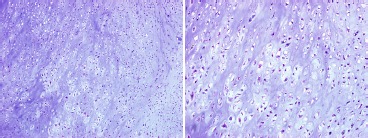

An incisional biopsy was performed shortly thereafter and showed the tissue had a grossly cartilaginous appearance. Microscopic exam (Figure 5) demonstrated a hypercellular field of disorganized chondrocytes and moderate nuclear atypia. A diagnosis of low-grade chondrosarcoma was made. The patient was therefore indicated for a wide resection, which we felt could be safely accomplished in the form of a type III limb-sparing pelvic resection.

Figure 5. Histopathologic sample obtained from the incisional biopsy stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (a) 10x magnification, (b) 20x magnification.

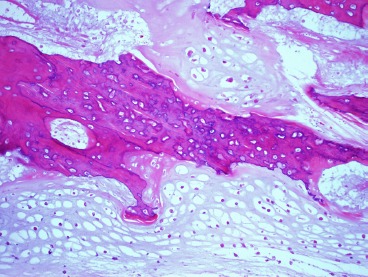

Microscopic inspection of the wide resection showed two foci of osteoid which initially appeared to be scaffolding onto normal host bone, raising the concern for a chondroblastic variant of osteosarcoma (Figure 6). However, after further review with our musculoskeletal pathologist (BRD) regarding the patient's history, the diagnosis was upheld as chondrosarcoma, grade II/III. This diagnosis was further corroborated by an independent review from another academic institution in the region. Based on this diagnosis no adjuvant treatment was administered. The patient has since been monitored with routine pulmonary surveillance with CT scans and local surveillance with radiographs and physical exam. She is now five years out from the surgical resection and is doing well with no obvious or reported functional limitations.

Figure 6. Histopathologic sample stained with hematoxylin and eosin obtained from the wide resection, 10x magnification.

Discussion

The first point of interest in this case is the rarity of encountering this lesion in a pediatric patient. Chondrosarcoma is an uncommon malignancy in general, and when encountered is most often in the adult population7. The overall annual incidence in the United States is approximately 1 in 200,0007. The National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) has identified only 9606 cases over an 18-year time period8 and the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program database of the National Cancer Institute has identified a total of 2890 cases over a 30-year time period7. Based on the SEER data, this is a disease primarily affecting adults with an average age 51. There have, however, been several small series from major referral centers reporting on chondrosarcoma in young patients2–5. The Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Boston revealed the diagnosis in only 12 pediatric patients (ages 6-20) over a 23 year time period2. The Mayo Clinic database revealed chondrosarcoma in only 14 pediatric patients (under age 17) among 634 total cases4. The largest series in the orthopaedic literature is from Memorial Sloan-Kettering and included 79 patients under the age of 21. This group was collected over a 54 year period5.

Even more rare is the likelihood that this patient’s lesion was a malignant transformation of a solitary exostosis. As stated in the case report, there is a visible lesion in an abdominal radiograph performed four years prior to the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma. How long that lesion had been present is unknown, as this was the first radiograph visualizing this patient’s pelvis. This initial lesion, seen in Figure 2, certainly has the appearance of an osteochondroma arising from the pubis. This lesion was believed to be solitary based on the skeletal survey demonstrating no other lesions. The available imaging supports that this patient had a solitary osteochondroma with malignant degeneration to a secondary chondrosarcoma. This malignant transformation is a well-described phenomenon, but is exceedingly rare in the pediatric population1,6,9. In one large series, Ahmed et al., reported that most cases of degeneration of osteochondromas to chondrosarcomas occurred in patients with multiple exostoses, and even then the average age was 34.9 years9. Young et al. reported seven of their 47 cases (15%) of adult chondrosarcoma appeared to be malignant degeneration of a solitary osteochondroma4. Huvos et al. reported the same finding in ten of their 79 cases (13%)5. The risk of malignant degeneration of a solitary osteochondroma in any age is estimated at less than one percent10,11. although there are reports of rates as high as 7.3%9 in large referral centers. Due to the difficulty in studying a disorder that is frequently asymptomatic and often goes undiagnosed, the true incidence of malignant transformation of solitary osteochondromas is unknown1. As noted previously, this patient had no evidence of that condition on her skeletal survey.

Lastly, there was considerable debate as to the diagnosis of the tumor: chondrosarcoma versus chondroblastic osteosarcoma. The difference between these diagnoses has significant treatment implications with the former typically treated surgically with wide resection and the latter also with a neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy regimen. Given the extremely low incidence of chondrosarcoma in the pediatric population, a high index of suspicion must be maintained to make the diagnosis and more common tumors (ie. osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma) must be ruled out. The diagnosis can be extremely difficult from a histopathologic standpoint. Chondrosarcoma is diagnosed by visualizing malignant cartilage producing cells along with infiltration of the marrow cavity and entrapment of preexisting bone tra- beculae12. Due to the appearance of what was eventually deemed enchondral ossification of the tumor in some fields, significant consideration was given towards a diagnosis of chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Osteosarcoma, chondroblastic variant, is more common in the pediatric patient8. This lesion is specifically characterized by sheets of spindle cells around lobules of chondroid with interposition of lacy osteoid12. The explanation for the osteoid seen in this case is that this represents so-called “normalization” of the chondrosarcoma (enchondral ossification of the tumor matrix onto entrapped pre-existing bone trabeculae). The diagnosis becomes difficult when there is this “normalization” of the chondrosarcoma, leaving patches of osteoid visible in portions of the tumor. An accurate diagnosis depends entirely upon pathologist interpretation of the slides. There are no known immunohistochemistry or genetic translocations that are believed to be helpful in differentiating chondroblastic osteosarcoma from chondrosarcoma. The Mayo Clinic authors noted that two of their initial 53 diagnoses of chondrosarcoma were changed on second review to chondroblastic variant of osteosarcoma4. This is a vital diagnostic consideration as these two diagnoses have very significant treatment implications. Treating a chondrosarcoma with chemotherapy would subject the patient to a 10 month course of extremely toxic and unnecessary therapy. However, treating a high-grade osteosarcoma without chemotherapy would be considered substandard care12. The patient in our case was treated without a chemotherapy regimen. She has been followed regularly and is now doing well with no evidence of local recurrence or metastases at five year follow-up, further lending support to the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma.

In summary, chondrosarcoma is a rare and difficult diagnosis in the pediatric patient. There is often considerable debate between chondrosarcoma and chondroblastic osteosarcoma. The diagnosis should be made based on history, imaging, and in consultation with a pathologist specializing in sarcoma and supplemented with additional opinions as necessary. The treatment implications of an accurate diagnosis are of paramount importance.

References

- 1.Pierz KA, Womer RB, Dormans JP. Pediatric bone tumors: osteosarcoma ewing’s sarcoma, and chondrosarcoma associated with multiple hereditary osteochondromatosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21-3:412–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aprin H, Riseborough EJ, Hall JE. Chondrosarcoma in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;166:226–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gadwal sR, Fanburg-Smith Jc, Gannon FH, Thompson Ed. Primary chondrosarcoma of the head and neck in pediatric patients: a clinicopatho-logic study of 14 cases with a review of the literature. Cancer. 2000;88-9:2181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young CL, Sim FH, Unni KK, McLeod RA. Chondrosarcoma of bone in children. Cancer. 1990;66-7:1641–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901001)66:7<1641::aid-cncr2820660732>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huvos AG, Marcove RC. Chondrosarcoma in the young. A clinicopathologic analysis of 79 patients younger than 21 years of age. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987;11-12:930–42. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198712000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierz KA, Stieber JR, Kusumi K, Dormans JP. Hereditary multiple exostoses: one center’s experience and review of etiology. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;401:49–59. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giuffrida AY, Burgueno JE, Koniaris LG, Gutierrez JC, Duncan R, Scully SP. Chondrosarcoma in the United States (1973 to 2003): an analysis of 2890 cases from the SEER database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91-5:1063–72. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damron TA, Ward WG, Stewart A. Osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing’s sarcoma: National Cancer Data Base Report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;459:40–7. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318059b8c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed AR, Tan TS, Unni KK, Collins MS, Wenger DE, Sim FH. Secondary chondrosarcoma in osteochondroma: report of 107 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;411:193–206. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000069888.31220.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin PP, Moussallem CD, Deavers MT. Secondary chondrosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 18-10:608–15. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garrison RC, Unni KK, McLeod RA, Pritchard DJ, Dahlin DC. Chondrosarcoma arising in osteochondroma. Cancer. 1982;49-9:1890–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820501)49:9<1890::aid-cncr2820490923>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenspan AJ, Gernot, Jundt G, Remagen W. Second. Vol. 1. Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2007. Differential Diagnosis in Orthopaedic Oncology; p. 529. [Google Scholar]