Abstract

Background

The prognosis for glioma remains dismal, and little is known about the final disease phase. To obtain information about this period, we surveyed caregivers of patients who were registered in the German Glioma Network and who died from the disease.

Methods

A questionnaire with 15 items, focusing on medical, logistic, and mental health support and symptom control during the final 4 weeks, was sent to caregivers. For some of the questions, a scale from 1 (inadequate) to 10 (excellent) was used.

Results

Of 1655 questionnaires, 605 were returned (36.6%) and evaluated. We found that 67.9% of the patients were taken care of at home for the last 4 weeks; 47.7% died at home, 22.6% died in hospitals, and 19.3% died in hospice facilities. Medical support was provided by general practitioners in 72.3% of cases, by physicians affiliated with a nursing home or hospice in 29.9%, and by general oncologists in 17%. Specialized neuro-oncologists were involved in 6%. The caregivers ranked the medical support with a mean of 7.2 (using a 10-point scale), nursing service with 8.1, and mental health support with 5.5. In 22.9% of cases, no support for the caregivers themselves was offered by medical institutions.

Conclusions

Although these data reflect the caregivers' subjective views, they are useful in understanding and improving current patterns of care. While patients and their caregivers are supported mainly by neuro-oncologists for most of the disease phase, the end-of-life phase is managed predominantly by general practitioners and specialists in palliative care. Close cooperation between these specialties is necessary to meet the specific needs of glioma patients.

Keywords: glioma, palliative care, supportive therapy

The disease course of glioma is highly variable, but with its devastating long-term prognosis, it is an immense challenge to patients and their social environment.1 Unlike most other types of cancer, by affecting neurological integrity gliomas may influence physical abilities, cognitive function, mood, and personality.2–4 At the final stage of the disease, caregivers are often unprepared and inadequately supported to address the needs of a patient suffering from impaired cognition, disorientation, impairment of consciousness, seizures, incontinence, and other complex neurological deficits.5–8 Therapy and support provided by specialized neuro-oncologists is given mostly in the phase of active treatment against glial tumors. However, in the final stage, when neuro-oncologists become less involved, little is known about the symptoms and particular needs of glioma patients, and even less is known of their caregivers' needs. There is presumably a “neuro-oncological gap” of adequate support, with many patients not receiving optimal palliative care, such that the burden of care often falls on patients' families and caregivers, assisted by professionals with no specialized neuro-oncological expertise.9 Thus, to improve the clinical care of glioma patients in the end stage of the disease, a thorough evaluation of the current situation is necessary. The survey undertaken here was designed not only to assess patterns of care but also to identify shortcomings in care with respect to patients' distress and that of their caregivers and social environment. Understanding these patterns of care in the context of the physical decline experienced by patients with glioma may enable the provision of adequate supportive care and appropriate communication when patients and caregivers need it most.10,11

In this context, the large, well-documented database of the German Glioma Network (GGN), a clinical research network sponsored by the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe), provides a unique opportunity to identify the following trends in the end-of-life care of glioma patients: the individuals providing care for the patients, the location of patients during the final phase and subsequent death, and the support available to caregivers.

Patients and Methods

Patients who died from a brain tumor at least 3 months before inclusion in this study and their caregivers were selected from the database of 7 clinical centers of the GGN (Bochum, Bonn, Düsseldorf, Dresden, Freiburg, Hamburg, and Munich) (www.gliomnetzwerk.de). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their inclusion in the GGN. Data collection procedures received approval from the local ethical committees of the participating centers. An additional ethics approval for the process of collecting data from the caregivers of the patients, which was not integrated into the initial ethical approval, was obtained. Selection criteria for this study were a glial cerebral tumor, as diagnosed by the local neuropathologist and confirmed by the German Brain Tumor Reference Center, and death at least 3 months prior to inclusion in the study. The questionnaires were sent to the patients' last address documented in the GGN database with a letter explaining the study purpose and design and a return envelope, with the assumption that using the patients' address would ensure that the most important caregiver was contacted. Due to the sensitivity of the matter of the survey, reminder letters or phone calls to the caregivers to increase the return rate were not used. Each questionnaire consisted of 15 questions and a space to give an individual comment. The questions focused on the last 4 weeks before the death of the patients. In 6 questions, a 10-point scale between 1 (inadequate) and 10 (excellent) was used (Table 1). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software for chi-square and Mann–Whitney U-tests.

Table 1.

Questions, summary

| • Place of palliative care during the final 4 weeks and place of death (2 questions) |

| • Supporting physician during the last 4 weeks |

| • Medical support for end-of-life problems (intracranial pressure, epilepsy, nausea, nutrition, dysphagia, depression, palsy, incontinence, consciousness) |

| • Information source for caregivers (other than physician) |

| • Supporting/contact person for caregivers (2 questions) |

| • Financial problems due to caring for patient |

| • Nonmedical support during the last 4 weeks |

| • Counseling by physician with regard to palliative care (2 questions) |

| • Caregivers' perception of patients' support during the last 4 weeks (by medical professionals, mental health professionals, or nurses) (3 questions) |

| • Use of alternative therapies during the last 4 weeks |

Results

Of the 1655 questionnaires sent out, a total of 605 were available for evaluation, representing an overall return rate of 36.6%. Because 443 questionnaires (27%) were returned to sender due to incorrect addresses (relatives/caregivers no longer living at the documented address), the actual return rate (questionnaire received and the respondents willing to answer) was 50.1%. The median age of patients in the study was 58.8 years (range, 17.6–86.7 y), and 63.6% were men. Overall survival across all histological subtypes was 2.3 years, and progression-free survival was 1.1 years. The distribution of histological subtypes was as follows: 13.3% were diagnosed with a WHO grade II tumor, 15.4% with a WHO grade III tumor, and 71.3% with a WHO grade IV tumor (according to the German Brain Tumor Reference Center; Table 2). Comparing our study population with the whole study population of the GGN (>4000 patients), some differences were seen in regard to age (older patients in our study group), gender (more men in our study group), and histology (higher rate of malignant glioma in our study group; Table 3). These differences were in part expected because we analyzed deceased patients, and therefore it was to be expected that the rate of high-grade gliomas and the median age would be higher than in the overall cohort. Regarding the gender distribution, we can only speculate that female caregivers may be more motivated to return the questionnaire in the sense of being a caregiver beyond the patients’ death.

Table 2.

Subgroups

| Age, y (n) | <20–40 (75) | 41–60 (167) | 61–80+ (324) |

| Gender (n) | Male (360) | Female (219) | |

| Histology (n) | WHO II, 13.3% (74) | WHO III, 15.4% (86) | WHO IV, 71.3% (398) |

| Survival (n) | <1 y, 42.1% (238) | 1–3 y, 40.6% (231) | |

| 3–5 y, 7.6% (43) | >5 y, 9.7% (56) |

Table 3.

End-of-life (EOL) study population vs whole GGN study population

| EOL Group (n = 605) | GGN Group (n = 4053) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y (range) | 58 (17–86) | 52 (17–88) |

| Gender | Male, 63.6% | Male, 58.7% |

| Female, 36.4% | Female, 41.3% | |

| Histology | WHO I, 0% | WHO I, 5.3% |

| WHO II, 13.3% | WHO II, 26.4% | |

| WHO III, 15.4% | WHO III, 19.1% | |

| WHO IV, 71.3% | WHO IV, 49.2% |

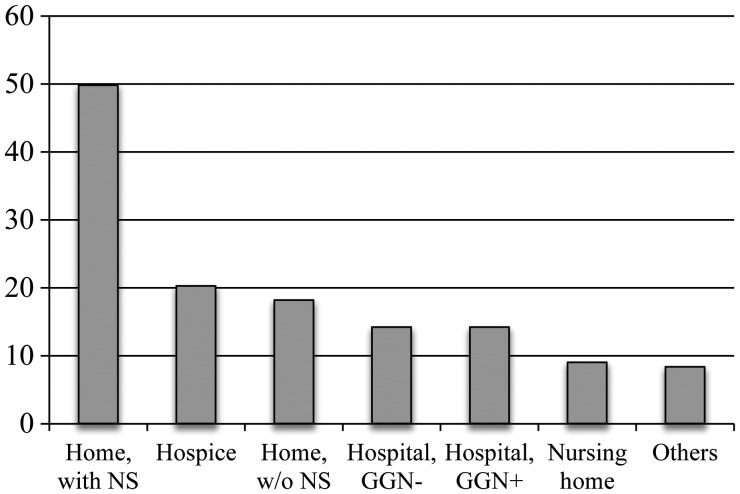

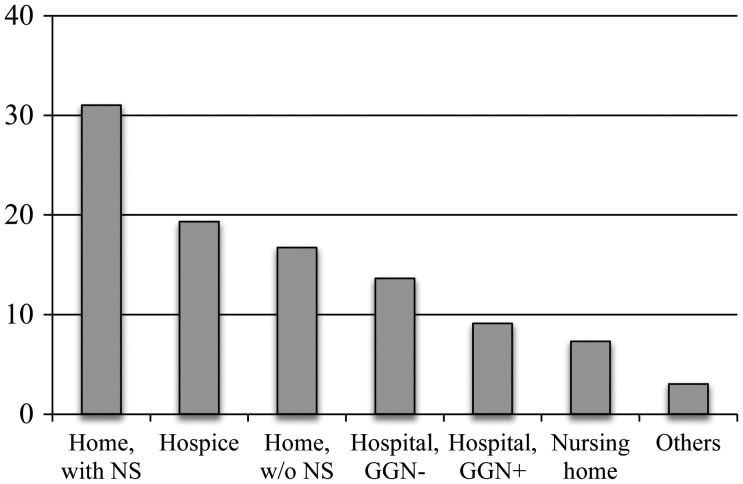

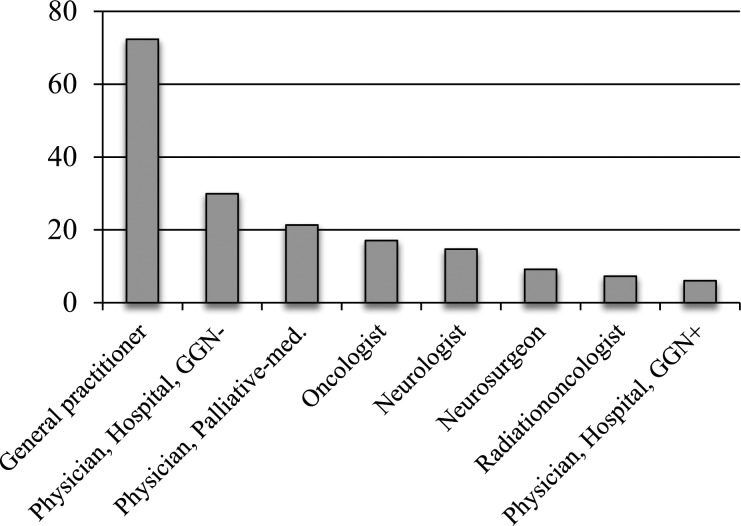

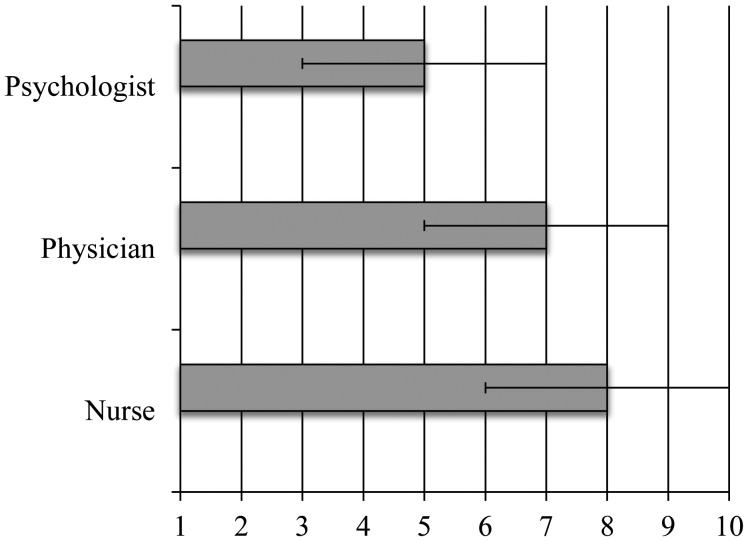

Sixty-eight percent of the patients received care at home during the final 4 weeks of the disease; 49.8% of these had the support of a nursing service, and 18.2% did not. In 28.4% of all cases in the study, patients spent at least some time during their final 4 weeks in hospitals (equally distributed between hospitals affiliated with the GGN and those not affiliated). Almost one-third of the patients received 24-h professional care outside of hospitals (20.2% in hospices and 9% in nursing homes; Fig. 1). Although 68% of all patients stayed at home in their final disease period, many were moved to a 24-h care institution in the final days, so only 47.7% of all patients died in their home environment (31% of these with the support of a nursing service and 16.7% without). Of the patients who did not die at home, 22.7% died in hospitals (13.6% not affiliated with the GGN and 9.1% affiliated with the GGN), 19.3% died in a hospice facility, and 7.3% died in a nursing home (Fig. 2). In summary, only a small portion of patients who, during the active therapy of their disease, were tightly bound to neuro-oncological specialists in the GGN were supported by these centers during the final phase of the disease. Accordingly, the neuro-oncologists of the GGN were not the primary providers of professional advice and care during the final phase of the disease; they were involved in only 6.1% of the cases, with 72.3% of the patients receiving care from general practitioners. Only 29.9% of all cases involved physicians from hospitals that did not belong to the GGN, and 21.3% of patients received care from physicians who specialized in palliative medicine or served as consultants to nursing homes or hospice facilities (Fig. 3). In 47.2% of cases, caregivers mentioned 1 primary physician; in 34.8%, 2; and in 18%, 3 or more. In the cohort of 2 physicians, the combination of general practitioner plus oncologist was seen in 37.9%, the combination of general practitioner plus neurologist in 29.1%, and the combination of general practitioner plus physician associated with the GGN (either neurologist or neurosurgeon) in 12.1%. Various other combinations were seen in <10%. The results in regard to the quality of care felt by caregivers did not differ between these groups. Using a 10-point scale (1 = inadequate, 10 = excellent) to judge the quality of medical and mental health and nursing service support during the end-of-life phase, the highest score was given to nursing services (median 8, SD 2), followed by support from physicians (median 7, SD 2). Mental health support was rated with a median score of only 5 (SD 2) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of place of care during the final 4 weeks (%). NS, nursing service; GGN+/−, hospital affiliated with GGN or not. The total is >100% due to >1 place of care during the last 4 weeks.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of place of death (%). NS, nursing service; GGN+/−, hospital affiliated with GGN or not.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of primary physician care during the final 4 weeks (%). GGN+/−, hospital affiliated with GGN or not. The total is >100% due to the possibility of >1 answer.

Fig. 4.

Caregivers' perception with regard to overall support from various occupational groups, mean ± SD. Scale: 1 = inadequate, 5 = fair, 10 = excellent.

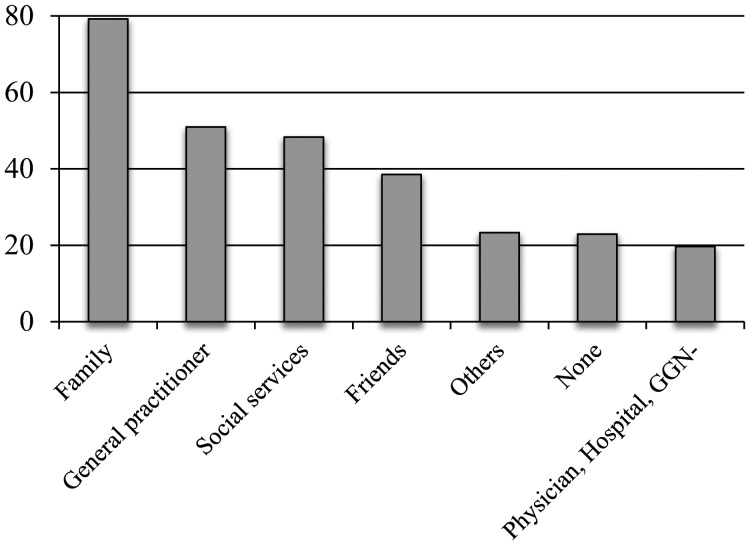

In addition to their perception of support received by patients, caregivers were asked about the support available to themselves in the stressful end-of-life situation. Most of the support came from nonprofessional sources, such as family (79.2%) and friends (38.6%). Professional support was offered by general practitioners (51%) and social services (48.3%). Many caregivers (23%) reported that they received no support during the final phase of caring for their family member (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Medical and nonmedical support for caregivers (%). GGN−, hospital not affiliated with GGN. The total is >100% due to the possibility of >1 answer.

When asked whether alternative/complementary therapies were used by caregivers to relieve the patients' symptoms during the final phase, 11.1% answered positively. A considerable number (17.8%) of caregivers stated that they experienced financial difficulties during the end-of-life phase. Caregivers were also asked whether they were satisfied with the support of their primary physician with regard to common symptoms occurring during the final disease phase (Table 1); ∼54.4% of the respondents were generally satisfied. According to the caregivers, treated well were dysphagia (72.9%), incontinence (70.8%), and epilepsy (63.8%), whereas nausea (49.4%), nutritive issues (36.2%), and cognitive deficits (26.3%) were the symptoms reported to be treated least effectively.

To detect any possible influences of patients' individual parameters, the answers were stratified for age, histology, sex, and overall survival (Table 3); however, no statistically significant differences were observed. The only detectable trend was observed in the subgroup of younger patients (<20–40 y) with WHO grade II and long overall survival across all histological subtypes. This cohort received medical support from neurologists in 30.1% of the cases compared with only 14.3% of cases receiving such support in the overall study population, and only a small proportion of patients in this cohort spent their final 4 weeks in a nursing home (2.3% vs 9% in the overall study population). In addition, the younger cohort sought more information about the end-of-life phase than did the overall study population.

Due to the retrospective study design, the interval from submission of the questionnaire to caregivers to patients’ deaths was between 3 months and 7 years. In order to evaluate whether differences were seen, we compared 100 patients with the longest interval between questionnaire and death (6–7 y) with 100 patients with the shortest interval between questionnaire and death (1 y). Significant differences were identified in 4 parameters. First the rate of palliative-care physicians involved in patient care increased in the observed period from 13.5% to 30.9%; second, non-GGN-associated hospitals as place of death decreased from 17.7% to 6.3%; third, the Internet as information source for caregivers increased from 25.3% to 40.6%; and finally, the rate of insufficient support for caregivers decreased from 33% to 15.3%. These data demonstrate that retrospective surveys may differ in regard to results depending on the timepoint of evaluation, which is in part inevitable in the retrospective context (Table 4).

Table 4.

Time-resolved analysis of questioned cohorts with respect to length of interval between receiving questionnaire and death of patient

| Total | Earliest 100 Patients | Recent 100 Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician, palliative medicine | 21.3% | 13.5% | 30.9% |

| Place of death, non-GGN hospital | 13.6% | 17.7% | 6.3% |

| Information source, Internet | 31.7% | 25.3% | 40.6% |

| Support of caregivers, none | 23.0% | 33.0% | 15.3% |

Among caregivers, 54.3% used the opportunity to express their thoughts on this topic in the free comment section. Besides positive comments regarding the end-of-life care (26% GGN, 65.6% outpatient), the caregivers reported the lack of psycho-oncological support (63.4%), insufficient physician/caregiver communication (42.9%), insufficient logistic support in regard to technical support/devices for the home care of the dying glioma patient (22.1%), and problems in regard to transfers of patients to hospitals in cases of acute deterioration not manageable by caregivers themselves (19.1%).

Discussion

In recent years, progress has been made in the medical management of glioma patients. Nevertheless, additional efforts are needed to improve supportive care and address end-of-life issues adequately. In general, the main goals of end-of-life care are to offer adequate symptom control, avoid inappropriately prolonging the dying process, and provide psychological support to meet the emotional needs of patients and caregivers. Although the data in this study on the terminal phase of glioma patients represent the caregivers' views on this topic and are therefore subjective, they may aid in understanding and improving current patterns of care.

An analysis of the location of palliative care during the final 4 weeks and subsequent death showed that about three quarters of the patients were able to stay at home, and almost half of the patients died at home. A large portion of the remaining patients in the study spent this period in hospitals and died there, in some cases leading to unsatisfactory situations for patients and caregivers, as indicated in the supplemental comments given by the caregivers in the questionnaires. However, hospitals also represented an adequate alternative for caregivers when the patients' acute symptoms became impossible to manage at home. The inability to adequately handle symptoms of patients not enrolled in palliative home-care programs typically leads to rehospitalization, increasing the burden on health care budgets, and more importantly, to the worsening of patients' and caregivers' quality of life.12 Although the GGN university hospitals are not primarily involved in end-of-life care, neuro-oncologists should be prepared to offer logistic advice and provide help in acute situations.

The opinions as to whether multidimensional care in the end-of-life phase of glioma patients should be within the scope of practice of general practitioners are mixed among these practitioners.10,13 As shown in our survey, patients and their caregivers are supported mainly by neuro-oncology centers during the initial disease phase, while the end-of-life phase is supported predominantly by general practitioners. It is thus of paramount importance to include specific neuro-oncological expertise (eg, dosing and duration of steroids and management of headache or seizures) for all aspects of patient management.14 Due to the low incidence of glioma, general practitioners may be unfamiliar with the natural course of disease progression and may require education and strong communication with neuro-oncology specialists to offer the best medical and palliative care to patients and to reduce unnecessary hospitalization.15

Several studies indicate that taking care of a patient with a brain tumor can have an enormous impact on a caregiver's life.16 Financial problems and changes in relationships and responsibilities are among the burdens caregivers may carry.17 The extent to which this was experienced (17%) is still worrisome but indicates that within the German social system, the majority of affected families are sufficiently cared for. Moreover, brain tumor patients' symptoms, including cognitive deficits, anxiety, and aggressive behavior, may cause subsequent distress to caregivers, negatively affecting their quality of life and thus their ability to cope with their new tasks. As determined from other studies, caregivers face the risk of becoming increasingly involved in patient care, subsequently isolated, and eventually unable to continue with their daily lives. Patients and caregivers have reported anxiety and distress resulting from social isolation, stigmatization, feeling misunderstood, and an inability to talk about their feelings or situations.18 Few studies evaluate the quality of life of untrained caregivers (eg, partners or family members) of brain tumor patients. Janda et al19 reported that glioma patients and their caregivers had a clinically significant reduction in quality of life compared with the general population. Understanding the necessities and gaps in specific education for the end-of-life phase of brain tumor patients and the provision of adequate support may greatly improve the negative impressions reported in such situations. Because caregivers described substantial deficits in mental health support for themselves, it is important to expand these services.20,21

Although the number of patients evaluated in this study is large, some possible limitations should be addressed. All of the patients in our study had been included in the database of the GGN; they had thus been treated in university medical centers with a neuro-oncological focus. Therefore, conclusions drawn from our data may not apply to patients treated in less specialized centers or to those treated in other countries due to differences in the structure of health care systems. Nevertheless, we obtained valuable information about the final disease stage of glioma patients and identified opportunities to improve care during this stage, helping both patients and caregivers and reducing the burden on caregivers. Despite the limitations of the study (the retrospective approach and the low return rate of questionnaires), these data may lead to a broader discussion of the patterns of care of glioma patients and hopefully serve as a starting point for further prospective studies in other countries.

In summary, we show that despite valuable research efforts to improve the treatment of brain tumors that focus on tumor biology and refinements to surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, there is also room to improve aspects of care in the end-of-life situation. An integrative approach for glioma patients, from diagnosis to death, could potentially reduce the burden felt by caregivers in the final period.

Funding

The German Glioma Network is supported by the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe 70-3163-Wi 3).

Conflict of Interest. O. H. received speaker's honoraria from Medac and Cyberonics. T. M. received speaker's honoraria from Archimedis Pharma and Cyberonics. J.-C.T. received speaker's honoraria from MerckSerono and Roche and served on advisory boards of MerckSerono and Roche. J.S. has received research grants from Deutsche Krebshilfe and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. M.W. has received research grants from Antisense Pharma, MerckSerono, and Roche and honoraria for lectures or service on advisory boards from Antisense Pharma, Magforce, MerckSerono, MSD, and Roche.

Acknowledgments

This work contains major parts of the doctoral thesis of Eva Vogeler, MD, to be submitted to the Fachbereich Medizin at the University of Hamburg. We thank Sabine Winkler and Monique Beyer, both study nurses at the Neuro Oncology Center Hamburg, for coordinating and collecting the data for this study.

References

- 1.Osoba D, Brada M, Prados MD, Yung WK. Effect of disease burden on health-related quality of life in patients with malignant gliomas. Neuro-Oncol. 2000;2(4):221–228. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/2.4.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heimans JJ, Taphoorn MJ. Impact of brain tumour treatment on quality of life. J Neurol. 2002;249(8):955–960. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taphoorn MJB, Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumors. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(3):159–168. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taphoorn MJ, Stupp R, Coens C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with glioblastoma: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(12):937–944. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batchelor TT, Byrne TN. Supportive care of brain tumor patients. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2006;20(6):1337–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConigley R, Halkett G, Lobb E, Nowak A. Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: a time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat Med. 2010;24(5):473–479. doi: 10.1177/0269216309360118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberndorfer S, Lindeck-Pozza E, Lahrmann H, Struhal W, Hitzenberger P, Grisold W. The end-of-life hospital setting in patients with glioblastoma. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(1):26–30. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L. Psychosocial and supportive-care needs in high-grade glioma. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(9):884–891. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arber A, Faithfull S, Plaskota M, Lucas C, de Vries K. A study of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour and their carers: symptoms and access to services. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2010;16(1):24–30. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.1.46180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SE, Kendall M, Morris PG, Murray SA. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. CMAJ. 2012;184(7):373–382. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalili Y. Ongoing transitions: the impact of a malignant brain tumour on patient and family. Axone. 2007;28(3):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pace A, Metro G, Fabi A. Supportive care in neurooncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(6):621–626. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32833e078c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taillibert S, Laigle-Donadey F, Sanson M. Palliative care in patients with primary brain tumors. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16(6):587–592. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000142075.75591.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daly FN, Schiff D. Supportive management of patients with brain tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7(10):1327–1336. doi: 10.1586/14737175.7.10.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pace A, Di Lorenzo C, Guariglia L, Jandolo B, Carapella CM, Pompili A. End of life issues in brain tumor patients. J Neurooncol. 2009;91(1):39–43. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9670-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sizoo EM, Braam L, Postma TJ, et al. Symptoms and problems in the end-of-life phase of high grade glioma patients. Neuro-Oncol. 2010;12(11):1162–1166. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley SE, Sherwood PR, Kuo J, et al. Perception of economic hardship and emotional health in a pilot sample of family caregivers. J Neurooncol. 2009;93:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9778-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keir ST, Guill AB, Carter KE, Boole LC, Gonzales L, Friedman HS. Differential levels of stress in caregivers of brain tumor patients—observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(12):1258–1261. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janda M, Steginga S, Langbecker D, Dunn J, Walker D, Eakin E. Quality of life among patients with a brain tumor and their carers. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(6):617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pace A, Di Lorenzo C, Capon A, et al. Quality of care and rehospitalization rate in the last stage of disease in brain tumor patients assisted at home: a cost effectiveness study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(2):225–227. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schubart JR, Kinzie MB, Farace E. Caring for the brain tumor patient: family caregiver burden and unmet needs. Neuro-Oncol. 2008;10(1):61–72. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2007-040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]