Abstract

Background and Purpose

Resting and reactive hyperemic leg blood flows are significantly reduced in the paretic compared with the non-paretic limb after disabling stroke. Our objective was to compare the effects of regular treadmill exercise (TM) to an active control regimen of supervised stretching (CONTROL) on peripheral hemodynamic function.

Methods

This intervention study utilized a randomized, controlled design, wherein participants were randomized with stratification according to age and baseline walking capacity to ensure approximate balance between the two groups. Fifty-three chronic, ischemic stroke participants (29 TM and 24 CONTROL) with mild to moderate hemiparetic gait completed bilateral measurements of lower leg resting and reactive hyperemic blood flow using venous occlusion strain gauge plethysmography, before and after the 6-month intervention period. Participants also underwent testing to track changes in peak aerobic fitness (VO2 peak) across time.

Results

Resting and reactive hyperemic blood flows were significantly reduced in the paretic compared with the non-paretic limb at baseline prior to any intervention (-28% and -34%, respectively, p<0.01). TM increased both resting and reactive hyperemic blood flow in the paretic limb by 25% compared to decreases in CONTROL (p<0.001, between groups). Similarly, non-paretic leg blood flow was significantly improved with TM compared to controls (p<0.001). VO2 peak improved by 18% in TM and decreased by 4% in CONTROL (p<0.01, between groups), and there was a significant relationship between blood flow change and peak fitness change for the group as a whole (r=.30, p<0.05).

Conclusion

Peripheral hemodynamic function improves with regular aerobic exercise training after disabling stroke.

Keywords: Blood Flow, Exercise, Stroke, Hemiparesis

INTRODUCTION

Disabling stroke causes substantial structural and metabolic abnormalities in the tissues of the hemiparetic leg (1-4), resulting in unilateral deficits that disproportionately contribute to systemic cardiovascular risk and overall disability (5). Paretic limb vasomotor disturbances are among the abnormalities observed by our lab (6) and others (4, 7, 8). We previously reported a 35% reduction in reactive hyperemic blood flow in the paretic leg compared to the non-paretic side in a small number of stroke survivors (6). These findings suggest that stroke-induced hemodynamic change is likely a major contributor to systemic cardiovascular risk, representing a rehabilitation target when addressing the metabolic and functional disturbances so prevalent in this population (9-11).

Some evidence supports the use of regular exercise to improve endothelial flow-mediated vasodilatation in healthy elderly (12-14) and a variety of disease conditions including diabetes, hypertension, peripheral arterial disease, chronic heart failure, and spinal cord injury (15-21). However, little is known about vascular adaptive capacity in stroke survivors. No studies have assessed the use of progressive, task-oriented aerobic training for modifying the known decrements in hyperemic blood flow in the paretic limb of stroke survivors. For this reason, it remains uncertain whether stroke survivors can perform aerobic exercise at levels requisite to induce vasomotor adaptations in the chronic phase of recovery. Nevertheless, preliminary support for the use of exercise to improve blood flow after stroke is provided by Billinger and colleagues (8). They utilized short term (4 weeks, 3x/ week) single leg extension/flexion activity in a small number of sub-acute stroke survivors to show that femoral artery basal blood flow could be improved with resistance training. Still, measures of flow-mediated vasodilatation have never been reported in the context of assessing exercise adaptation after stroke. Hence, further studies are now required to more thoroughly assess the use of commonly applied task-oriented exercise models for eliciting structural and functional vascular adaptation.

We designed the current randomized, controlled trial to test the hypothesis that regularly performed treadmill exercise therapy would be more effective for producing peripheral hemodynamic adaptations than an attention-matched control intervention consisting of elements of conventional stroke rehabilitation.

METHODS

Subjects

Participants were recruited from the University of Maryland Medical System and the Baltimore VA Medical Center referral networks. Chronic hemiparetic stroke patients (>6 months) who had completed all conventional physical therapy were sought. Potential participants had mild to moderate hemiparetic gait and demonstrated preserved capacity for ambulation with an assistive device. Baseline evaluation included a medical history and examination. Patients with a history of vascular surgery, vascular disorders in the lower extremities, or symptomatic peripheral arterial occlusive disease were excluded. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for research involving humans at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Blood Flow testing

All subjects were assessed under standardized conditions following an overnight fast between 9 and 10 AM. Subsequent to their arrival at the medical center they were led to a room of consistent temperature (23-25 C) and low ambient noise level. They were then instructed to rest in the supine position for 20 minutes while testing preparations were undertaken. Calf blood flow in both legs was obtained separately under resting and reactive hyperemic conditions using venous occlusion mercury strain-gauge plethysmography (model TL-400, D.E. Hokanson, Inc., Bellevue, WA.). The right leg was always measured first. Before testing each leg, the calf was elevated above the level of the heart using a dedicated foam pad under the foot. A mercury-filled strain gauge was subsequently secured around the widest section of the lower leg. The test for resting calf blood flow began by excluding foot blood flow with ankle cuff inflation to 220 mmHg. Basal or resting blood flow was taken as an average of 4 measurements recorded when the thigh cuff was inflated to 50mmHg. Reactive hyperemic blood flow was assessed by inflating the thigh cuff to at least 200 mmHg for 3 minutes to stop blood flow to the calf region. A rapid thigh cuff inflator was used for this purpose, and upon release was immediately set to 50 mmHg and re-inflated for measurement of peak reactive hyperemic blood flow. Resting and hyperemic blood flow measurements were obtained in the paretic and non-paretic legs and both before and after the 6-month intervention period. Test-retest reliability assessment for peak leg blood flow in 10 stroke participants showed an intraclass reliability coefficient (R) of 0.89.

Exercise Testing

A physician-supervised treadmill tolerance test at no incline was first performed to assess gait safety and to select walking velocity for subsequent peak exercise testing and treadmill training. Participants minimized handrail support, and a gait belt was worn for safety. For the graded treadmill screening test, all participants who achieved adequate exercise intensities without signs of myocardial ischemia or other contraindications for participating in aerobic training were deemed suitable for entry. The 12-lead ECG printout from each screening treadmill test was reviewed for myocardial ischemia and other cardiac abnormalities by a cardiologist prior to granting clearance for ongoing study participation. Following a rest interval of at least one week to avoid the confounding effects of fatigue, treadmill testing with open circuit spirometry was conducted to measure VO2 peak. This was done using a previously described treadmill testing protocol for stroke survivors (22). Peak aerobic testing was repeated at the post-intervention time point.

Randomization

Participants were randomized to TM or CONTROL following baseline testing using a blocked allocation schema and a computer-based, pseudo-random number generator. Age and severity of deficits were considered in the randomization design. Specifically, separate blocked randomizations were performed according to age (<65 vs. ≥ 65 yrs.) and self-selected walking speed (< 0.44 m/sec vs. ≥ 0.44 m/sec), given the potential impact of these factors on rehabilitation outcomes. Because this was an exercise intervention study, participants could not be blinded to treatment assignment or study hypotheses. An additional limitation of this study is that personnel resource constraints prevented blinding of trainers and outcomes testers, adding another potential source of unwanted bias to the trial. The possibility of a trainer effect was minimized by having the same staff conduct training sessions for both TM and CONTROL.

Intervention Protocols (6 months)

The TM protocol consisted of three 40-minute sessions per week at a target aerobic intensity of 60 -70 % heart rate reserve (HRR). Training started at low intensity (40-50% HRR) for 10 to 20 minutes and gradually progressed to target levels. Since these highly deconditioned individuals were initially incapable of continuous exercise, they started with discontinuous training. Handrail and harness support were utilized throughout. Additionally, heart rate (2-lead ECG, Polar Electro, Woodbury, NY) and blood pressure were monitored and recorded before, during and after each exercise session.

The CONTROL protocol provided matched exposure to staff, who aided participants in the performance of physical therapy exercises common to stroke. Participants performed 13 targeted active and passive supervised stretching movements of the upper and lower body (3x/ week for 30-40 minutes).

Data Analysis

Resting and reactive hyperemic blood flows were compared between the paretic and non-paretic legs using a dependent t-test. Repeated measures ANOVA (3-factors, group × leg × time, 2 × 2 × 2) was used to predict values of outcome variables across time, assessing for significant 3-way and 2-way interactions related to changes in both resting and reactive hyperemic blood flow. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess the strength of relationship between changes in blood flow and peak fitness. Baseline and repeated values are mean ± SD with a two-tailed p value of 0.05 required for significance.

RESULTS

Subjects

There were 10 lost to follow-up in the TM group (26%) and 17 lost to follow-up in the CONTROL group (41%). Dropouts in TM and CONTROL resulted from medical reasons unrelated to study procedures (n= 7 and 7, respectively) or general compliance issues (n= 3 and 10, respectively). There were no serious adverse events resulting from either of the intervention protocols. Of the 53 who completed, 29 (18 men, 11 women) were TM and 24 (11 men, 13 women) were CONTROL. At baseline, there were no significant differences between groups for age, height, weight, or BMI (Table 1). There were also no baseline differences between groups for peak fitness or timed walking speed, indicating that the groups were evenly matched in terms of functional capacity. Both the TM and CONTROL groups had approximately the same racial mix (55% and 54% African-American, respectively) and both groups had similar percentages of participants requiring assistive devices for ambulation. Participant physical and functional characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics by group

| Variable | TM (N=29) | CONTROL (n=24) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs.) | 62 ± 8 | 60 ± 8 | 0.27 |

| Weight (kg) | 82 ± 23 | 75 ± 16 | 0.19 |

| Height (cm) | 169 ± 11 | 169 ± 7 | 0.96 |

| BMI | 28.4 ± 6 | 26.1 ± 5 | 0.15 |

| Walking Speed (mph) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.75 |

| Peak Aerobic Capacity (ml/kg/min) | 14.1 ± 4.0 | 13.5 ± 3.6 | 0.54 |

Mean ± SD (yrs.=years, kg=kilograms, cm= centimeters, BMI=Body Mass Index, mph=miles per hour, ml/kg/min = milliliters per kilogram per minute, TM=Treadmill, N=Number, P=Probability)

Blood Flow differences between Paretic and Non-Paretic Legs

Comparison of resting calf blood flow in the paretic and non-paretic legs for the entire sample (n=53) at baseline revealed a significant 28% difference (1.8 ± 0.8 vs. 2.5 ± 1.1 ml/100 ml/min, mean ± SD, p<0.01). Likewise, post-ischemic reactive hyperemic blood was reduced by 34% (9.2 ± 5.1 vs. 13.9 ± 6.9 ml/100 ml/min, p<0.01) in the paretic limb compared to the non-paretic leg (n=53). These findings were in line with our prior work using a much smaller sample size (6).

Effects of TM vs. CONTROL on Peak Fitness

Evidence of an aerobic training effect in the TM group compared to CONTROL is provided by a significant time × group interaction for VO2 peak (p<0.01). Participants in the TM group had a mean improvement of 18% (14.1 ± 4.0 to 16.6 ± 5.64 ml/kg/min, mean ± SD) across time compared to a 4% decrease in CONTROL (13.5 ± 3.6 to 12.8 ± 3.9 ml/kg/min).

Effects of TM vs. CONTROL on Lower Leg Blood Flow (Figures 1 & 2)

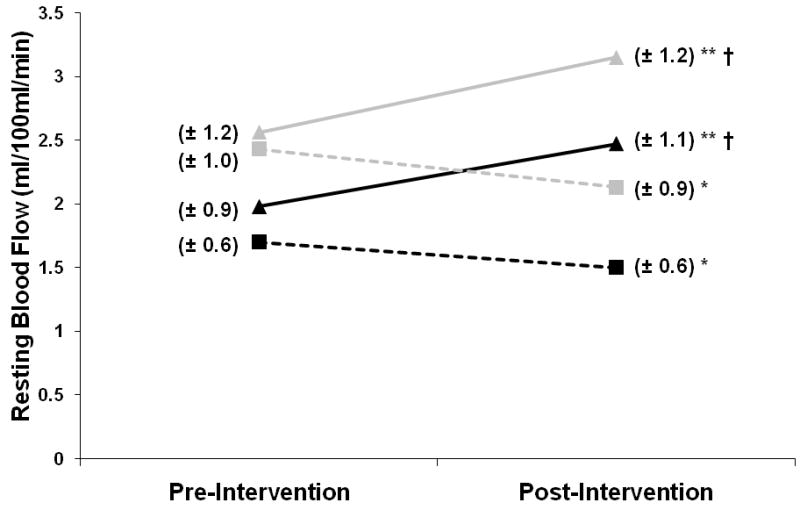

Figure 1.

Line graph depicting change in resting leg blood flow (y axis) across the intervention period (x axis). For the paretic leg (black lines), there was a significant increase in resting flow for the TM group (triangles, solid line) (p<0.001 within group,**) and a significant decrease for CONTROL (squares, dashed line) (p<0.05 within group, *). For the non-paretic leg (grey lines) there was also a significant increase for TM (p<0.001, within group **) as well as a decrease for CONTROL (p<0.05 within group, *). A 2-way interaction effect (time × group, p<0.001, †) indicated that change in TM was greater than change in CONTROL. Standard deviations are provided in parentheses next to each mean data point.

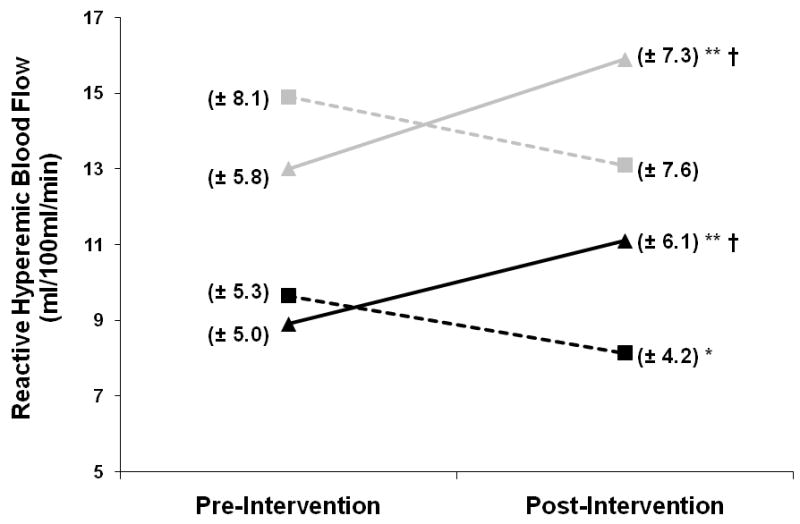

Figure 2.

Follows the exact same pattern as Figure 1, but represents change in reactive hyperemic leg blood flow across time.

Resting blood flow in the paretic and non-paretic legs increased with treadmill training by +25% and +23%, respectively (p<0.001, within group) (Figure 1). Conversely, those undergoing the control intervention experienced significant decreases in resting leg blood flow (p<0.05, within group) (Figure 1). Similarly, large increases in reactive hyperemic blood flow in both the paretic (+25%) and non-paretic (+22%) legs with treadmill training (p<0.001 within group) (Figure 2) contrasted with the decrease in paretic leg reactive hyperemic flow observed across the control intervention (p<0.05, within group). The decrease shown in Figure 2 for the non-paretic leg across the control intervention was not statistically significant. Three-factor ANOVA revealed that the 3-way interaction terms (group × leg × time) for both resting (F=0.768, p=0.383) and reactive hyperemic leg flow (F=0.638, p=0.426) were not significant, but that a 2-way interaction (group × time) did achieve significance for both outcomes (F= 40.2 and 34.9, respectively, p<0.001). This indicates that the differing pattern of the response between groups (TM vs. CONTROL) did not differ significantly by leg (paretic vs. non-paretic). Further, time × group interactions (P<0.001) indicate that the TM intervention was more effective for stimulating blood flow improvement compared to CONTROL. Although TM and CONTROL appear in Figure 2 to have different baseline non-paretic hyperemic flow measures (grey triangle vs. grey square), this difference was not significant by independent t-test.

Blood flow change vs. change in peak fitness

When blood flow changes were compared with changes in peak fitness for the group as a whole (n=53), there were small but significant associations for paretic side reactive hyperemic flow change (r=0.28, p=0.04) and non-paretic side resting flow change (r=0.30, p=0.03).

DISCUSSION

This is the first investigation aimed at determining whether stroke-associated vasomotor function abnormalities can be reversed with regular, task-oriented exercise. Our findings definitively show that progressive, task-oriented treadmill exercise therapy produces large reactive hyperemic blood flow improvements in both the paretic and non-paretic legs after stroke. Given the tight coupling between blood flow and the metabolic characteristics of tissues (4, 23), we propose that continued exercise therapy in the chronic phase of stroke recovery may be essential for altering the metabolic and functional decrements associated with unilateral tissue deterioration on the paretic side (1-3). Of course, longer term mechanistic studies starting in the earlier stages of stroke recovery will be needed to better support and develop this concept. Observations of concomitant decreases in blood flow parameters during our 6-month control intervention point toward the potentially devastating, rapidly developing vascular health consequences of sedentary living in the chronic phase of stroke recovery. Lastly, correlation between change in VO2 and change in limb blood flow provides additional rationale for adding sufficiently intense aerobic exercise to more conventional forms of stroke rehabilitation.

Earlier studies of blood flow and vasomotor regulation in hemiparetic humans conflicted, reporting either no change or elevated blood flow in the affected limbs (24, 25). However, our group (6) and others (4, 7, 8) have since produced preliminary evidence related to the detrimental effects of hemiparesis on limb blood flow in small numbers of subjects. The current study, with 53 participants (nearly 3x the number of our previous report), serves as additional support for the idea that stroke-associated hemiparesis produces marked effects on peripheral blood flow dynamics. Notably, our previous and current findings in stroke survivors suggest that reactive hyperemia in the paretic leg may average approximately half of an age-matched healthy person (26). Additional context is provided by findings that our non-paretic leg reactive hyperemic blood flow measurements are similar to those previously reported for peripheral arterial disease claudicants (21). Potential mechanisms responsible for the observed unilateral changes in leg blood flow on the hemiparetic side remain an area of speculation, but may include altered autonomic function (27), enhanced sensitivity to endogenous vasoconstrictor agents (28), and altered histochemisty and morphology of the vascular network itself (29). Further, reductions in limb flow have previously been associated with higher proportions of type II muscle fibers (4), which is consistent with our findings of paretic-side fiber type shifts(3) and simultaneous atrophy (1). Finally, we have reported increased paretic leg skeletal muscle TNFα, which is known to impair endothelial vasodilatory function (30).

Stroke-related impairments in flow-mediated vascular function are clinically relevant, as peripheral dysfunction in the endothelium is reflective of systemic disturbances in the larger vascular network (31). One of the most important characteristics of vessels is the ability to produce changes in vasomotor tone as a result of physical and chemical stimuli, and to change blood flow and distribution according to local conditions (31). Disruptions in this capacity have been implicated in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome components (32) as well as functional impairment in humans (33). Vascular event risk is similarly impacted by blunted peripheral endothelial related vasomotor capacity (34). Hence, developing therapeutic strategies to address impairments in vasomotor function may be especially relevant in the high-risk, disabled stroke population.

The longitudinal findings of the current study are encouraging and consistent with the degree of exercise-induced vascular adaptation observed in prior investigations with non-stroke cohorts (12, 13, 15-21, 26, 35). Although methodological differences with respect to blood flow measurement techniques, training interventions and populations studied make comparisons between the current and other investigations challenging, some interesting similarities and contrasts emerge from the small number of blood flow related exercise trials performed to date. For example, the exercise-induced improvement in limb reactive blood flow among participants with hypertension (17) and peripheral arterial disease (21, 36) was 23% and 30-35%, respectively. This is not substantially different from the 27-30% relative improvements in healthy elderly (12, 26) or the 25% increase in our stroke survivors. Interestingly, Pierce et.al. (18) exposed heart transplant recipients to treadmill training and calf blood flow measuring procedures that were similar to the current study and observed a nearly identical improvement in reactive hyperemic flow (+22%). Billinger et. al. were the first to study blood flow adaptations to exercise after stoke, reporting 40% improvements in basal femoral artery hemodynamics by Doppler after 3 weeks of unilateral resistance training. Our study adds to the literature by measuring changes in flow-mediated dilation using a randomized, controlled design and a much longer 6-month aerobic exercise intervention protocol. Collectively, studies on exercise-induced blood flow changes support the idea that stroke survivors maintain similar vascular adaptive capacity to other healthy and diseased elderly population groups.

Among the limitations of the current study, beyond those already cited, was the failure to account for whether vascular adaptations were simultaneously occurring in non-trained vascular beds. Specifically, future studies involving stroke survivors might incorporate upper extremity blood flow measurements across lower body exercise interventions to assess the extent to which these interventions have a systemic effect on the vascular tree. Non-trained vascular beds have shown less adaptive capacity in some studies (18, 37), reporting increases in calf blood flow with no concomitant change in forearm blood flow. Conversely, Higashi et. al. (17) reported a 23% increase in peak vasodilation of resistance arteries of the forearm after a 12-week lower body exercise training program. This was in agreement with other studies (12) showing a systemic effect. Also, it would be useful to study the time course of adaption to training and detraining in chronic stroke, given evidence that these changes may occur more rapidly than previously believed (8, 18). A final limitation relates to the high number of drop-outs and the absence of an intention-to-treat analysis. Although the proportion of non-completers may have been fairly standard for exercise intervention studies of this nature, it is difficult to argue that drop-outs did not influence our results to some degree.

In summary, this study provides the first evidence in support of aerobic exercise rehabilitation for addressing hemodynamic disturbances after stroke. We report highly significant changes to resting and hyperemic blood flow in both the paretic and non-paretic legs following exposure to a progressive treadmill training regimen compared to participants exposed to elements of conventional stroke rehabilitation. Our cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons in the current trial compare favorably with prior investigations, suggesting vascular adaptations secondary to changes in vessel function and vascular remodeling. Future studies should consider assessments related to the non-trained vasculature as well as time course of adaptation.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of our loyal stroke survivors for their commitment to regular testing and exercise training visits. They are a great inspiration to all who are privileged to interact with them. Additionally, this study would not have been possible without the hard work of the Baltimore VA Exercise Physiology Staff. Their dedication to ensuring participant safety, treatment fidelity and general satisfaction is essential to the success of our exercise intervention trials.

Sources of Funding: Dr. Ivey was supported by NIA-K01 AG19242, and Dr. Ryan was supported by a VA career scientist research award. The authors also wish to acknowledge support from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Baltimore Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), National Institute on Aging (NIA), Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30-AG028747) and the Department of Veterans Affairs VA RR&D Exercise & Robotics Center of Excellence (Macko).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Ryan AS, Dobrovolny CL, Smith GV, Silver KH, Macko RF. Hemiparetic muscle atrophy and increased intramuscular fat in stroke patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1703–1707. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.36399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hafer-Macko CE, Yu S, Ryan AS, Ivey FM, Macko RF. Elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skeletal muscle after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2021–2023. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177878.33559.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Deyne PG, Hafer-Macko CE, Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Macko RF. Muscle molecular phenotype after stroke is associated with gait speed. Muscle and Nerve. 2004;30:209–215. doi: 10.1002/mus.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landin S, Hagenfeldt L, Saltin B, Wahren J. Muscle metabolism during exercise in hemiparetic patients. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;53:257–269. doi: 10.1042/cs0530257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivey FM, Macko RF, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE. Cardiovscular health and fitness after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2005;12:1–16. doi: 10.1310/GEEU-YRUY-VJ72-LEAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivey FM, Gardner AW, Dobrovolny CL, Macko RF. Unilateral Impairment of leg blood flow in chronic stroke patients. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:283–289. doi: 10.1159/000080353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams WC, Immis FJ. Resting blood flow in the paretic and nonparetic lower legs of hemiplegic persons: Relation to local skin temperature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:423–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billinger SA, Gajewski BJ, Guo LX, Kluding PM. Single limb exercise induces femoral artery remodeling and improves blood flow in the hemiparetic leg poststroke. Stroke. 2009;40:3086–3090. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.550889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivey FM, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE, Garrity BM, Sorkin JD, Goldberg AP, Macko RF. High prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism and poor sensitivity of fasting plasma glucose in the chronic phase of stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22:368–371. doi: 10.1159/000094853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivey FM, Macko RF. Prevention of Deconditioning after Stroke. In: Stein J, Harvey R, Macko RF, Winstein CJ, Zorowitz R, editors. Stroke Recovery & Rehabilitation. 1. New York: DemosMedical; 2009. pp. 387–404. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon NF, Gulanic M, Costa F, Fletcher G, Franklin BA, Roth EJ, Shephard T. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: An American Heart Association Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2004;109:2031–2041. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126280.65777.A4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desouza CA, Shapiro LF, Clevenger CM, Dinenno FA, Monahan KD, Tanaka H, Seals DR. Regular aerobic exercise prevents and restores age-related declines in endothelium-dependent vasodilation in healthy men. Circulation. 2000;102:1351–1357. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beere PA, Russell SD, Morey MC, Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB. Aerobic exercise training can reverse are-related peripheral circulatory changes in healthy older men. Circulation. 1999;100:1085–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyachi M, Tanaka H, Okajima M, Tabata I. Lack of age-related decreases in basal whole leg blood flow in resistance-trained men. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1384–1390. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00061.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hambrecht R, Fiehn E, Weigl C, Gielen S, Hamann C, Kaiser R, Yu J, Adams V, Niebauer J, Schuler G. Regular physical exercise corrects endothelial dysfunction and improves exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1998;98:2709–2715. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.24.2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Filippis E, Cusi K, Berria R, Buck S, Consoli A, Mandarino CJ. Exercise-induced improvement in vasodilatory function accompanies increased insulin sensitivity in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocinol Metab. 2006;91:4903–4910. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higashi Y, Sasaki S, Sasaki N, Nakagawa K, Ueda T, Yoshimizu A, Kurisu S, Matsuura H, Kajliyama G, Oshima T. Daily aerobic exercise improves reactive hyperemia in patients with essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1999;33:591–597. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce GL, Schofield RS, Casey DP, Hamlin SA, Hill JA, Braith RW. Effects of exercise training on forearm and calf vasodilation and proinflammatory markers in recent heart transplant recipients: a pilot study. Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008;15:10–18. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f0b63b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thijssen DH, Ellenkamp R, Smits P, Hopman MT. Rapid vascular adaptations to training and detraining in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lavrencic A, Salobir G, Keber I. Physical training improves flow-mediated dilation in patients with the polymetabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:551–555. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brendle DC, Joseph LJO, Corretti MC, Gardner AW, Katzel LI. Effects of exercise rehabilitation on endothelial reactivity in older patients with peripheral arterial disease. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:324–329. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macko RF, Katzel LI, Yataco A, Tretter LD, Desouza CA, Dengel DR, Smith GV, Silver KH. Low-velocity graded treadmill stress testing in hemiparetic stroke patients. Stroke. 1997 May;28:988–992. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.5.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg BR, Cohen KD, Sarelius IH. Direct coupling between blood flow and metabolism at the capillary level in striated muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2693–H2700. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg MJ, Skowland HV, Katke FJ. Comparison of circulation in the lower extremeties of hemiplegic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1968;49:467–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redisch W, Tangco FT, Werthheimer L, Lewis AJ, Steele JM. Vasomotor responses in the extremeties of subjects with various neurologic lesions. Circulation. 1957;15:518–524. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.15.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thijssen DHJ, de Groot PCE, Smits P, Hopman MTE. Vascular adaptations to 8-week cycling training in older men. Acta Physiol. 2007;190:221–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herbaut AG, Cole JD, Sedgwick EM. A cerebral hemisphere influence on cutaneous vasomotor reflexes in humans. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:118–120. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bevan R, Clemenson A, Joyce E, Bevan J. Sympathetic denervation of resistance arteries increases contraction and decreases relaxation to flow. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H490–H494. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.2.H490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozak P. Circulatory changes of the paretic extremeties after acute anterior poliomyelitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1968;49:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hafer-Macko CE, Yu S, Ryan AS, Ivey FM, Macko RF. Elevated tumor necrosis factor-alpha in skeletal muscle after stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2021–2023. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177878.33559.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korkmaz H, Onalan O. Evaluation of endothelial dysfunction: Flow-mediated dilation. Endothelium. 2008;15:157–163. doi: 10.1080/10623320802228872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind L, Lithell H. Decreased peripheral blood flow in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome comprising hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia. Am Heart J. 1993;125:1494–1497. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90446-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dinenno FA, Jones PP, Seals DR, Tanaka H. Limb blood flow and vascular conductance are reduced with age in healthy humans: relation to elevations in sympathetic nerve activity and declines in oxygen demand. Circulation. 1999;100:164–170. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gokce N, Keaney JF, Hunter LM, Watkins MT, Nedeljkovic ZS, Menzoian JA, Vita JA. Predictive value of noninvasively determined endothelial dysfunction for long-term cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral vascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1769–1775. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00333-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ballaz L, Fusco N, Cretual A, Langella B, Brissot R. Peripheral vascular changes after home-based passive leg cycle exercise training in people with paraplegia: A pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:2162–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gardner AW, Katzel LI, Sorkin JD, Bradham DD, Hochberg MC, Flinn WR, Goldberg AP. Exercise rehabilitation improves functional outcomes and peripheral circulation in patients with intermittent claudication: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:755–762. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dziekan G, Myers J, Goebbels U, Muller P, Reinhart W, Ratti R. Effects of exercise training on limb blood flow in patients with reduced ventricular function. Am Heart J. 1998;136:22–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]