Abstract

Increased spontaneous firing (hyperactivity) is induced in fusiform cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN) following intense sound exposure and is implicated as a possible neural correlate of noise-induced tinnitus. Previous studies have shown that in normal hearing animals, fusiform cell activity can be modulated by activation of parallel fibers, which represent the axons of granule cells. The modulation consists of a transient excitation followed by a more prolonged period of inhibition, presumably reflecting direct excitatory inputs to fusiform cells and an indirect inhibitory input to fusiform cells from the granule cell-cartwheel cell system. We hypothesized that since granule cells can be activated by cholinergic inputs, it might be possible to suppress tinnitus-related hyperactivity of fusiform cells using the cholinergic agonist, carbachol. To test this hypothesis, we recorded multiunit spontaneous activity in the fusiform soma layer (FSL) of the DCN in control and tone-exposed hamsters (10 kHz, 115 dB SPL, 4 h) before and after application of carbachol to the DCN surface. In both exposed and control animals, 100 µM carbachol had a transient excitatory effect on spontaneous activity followed by a rapid weakening of activity to near or below normal levels. In exposed animals, the weakening of activity was powerful enough to completely abolish the hyperactivity induced by intense sound exposure. This suppressive effect was partially reversed by application of atropine and was not associated with significant changes in neural best frequencies (BF) or BF thresholds. These findings demonstrate that noise-induced hyperactivity can be pharmacologically controlled and raise the possibility that attenuation of tinnitus may be achievable by using an agonist of the cholinergic system.

Keywords: Cholinergic modulation, tinnitus, DCN, plasticity, hyperactivity suppression

INTRODUCTION

Several lines of evidence point to fusiform cells as major generators of tinnitus-related hyperactivity in the cochlear nucleus. These cells provide the major throughput from the dorsal subdivision of the cochlear nucleus (DCN) to the inferior colliculus (IC). Cells with the properties of fusiform cells show higher levels of spontaneous activity in sound exposed animals than in unexposed controls (Brozoski et al., 2002; Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009; Shore et al., 2008), and the degree of hyperactivity examined as a function of depth below the DCN surface reaches a peak in the fusiform soma layer (FSL) (Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009; Middleton et al., 2011). Ablation of the DCN prevents induction of tinnitus following intense sound exposure (Brozoski et al., 2012) and abolishes noise-induced hyperactivity in the contralateral inferior colliculus (Manzoor et al., 2012), which is the main target of fusiform cell projections (Adams, 1979; Adams and Warr, 1976; Kane, 1974; Osen, 1972; Oliver, 1984). Thus, fusiform cells may contribute to the appearance of hyperactivity in their more rostral targets. If these cells are a major source of tinnitus-related hyperactivity, then it is to be expected that hyperactivity might be reducible by manipulating inputs that increase the degree of inhibition to fusiform cells.

One cell population that exerts a powerful inhibitory influence on fusiform cells is that of cartwheel cells. These cells are located in the superficial layer of the DCN, where they are driven by excitatory inputs from parallel fibers, the axons of granule cells. Cartwheel cells display complex waveforms with spikes that typically occur in bursts (Zhang and Oertel, 1993; Caspary et al., 2006; Manis et al., 1994; Waller and Godfrey, 1994; Davis and Young, 1997; Parham and Kim, 1995; Parham et al., 2000; Portfors and Roberts, 2007). Stimulation of parallel fiber inputs from granule cells results in excitation of bursting neurons (Waller et al., 1996; Davis and Young, 1997) and inhibition of fusiform cells in vitro (Manis, 1989; Davis et al., 1996; Davis and Young, 1997). In vivo studies show that activation of parallel fibers, by stimulating the non-auditory inputs to granule cells from the cuneate nucleus, often results in a suppression of spontaneous and stimulus-driven activity of fusiform cells, although a transient excitatory response is sometimes also observed (Waller et al., 1996; Davis et al., 1996; Davis and Young, 1997; Kanold and Young, 2001), presumably resulting from the direct excitatory input to fusiform cells from parallel fibers. The inhibitory effect suggests that activation of inputs to granule cells, which include both auditory and non-auditory sources, results in excitation of cartwheel cells and inhibition of fusiform cells.

One major source of input to the granule cell system that drives cartwheel cells comes from the branches of the olivocochlear bundle (Rasmussen, 1967). This bundle originates from neurons in the superior olivary complex (Warr, 1992) and is largely cholinergic (Godfrey et al., 1984; Rasmussen, 1967; Osen et al., 1984; Moore, 1988; Sherriff and Henderson, 1994). Although the main trunk of the bundle continues peripherally to innervate cochlear outer hair cells and the peripheral dendrites of type I primary afferent neurons, collaterals of this bundle enter the cochlear nucleus where they terminate in and around the granule cell domain (Godfrey et al., 1987a,b, 1990, 1997; Benson and Brown, 1990; Mellott et al., 2011; Shore and Moore, 1998; Schofield et al., 2011). Application of cholinergic agonists to the DCN results in activation of granule cells (Koszeghy et al., 2012) and increased bursting activity of their inhibitory targets, the cartwheel cells (Chen et al., 1994; 1999; Chang et al., 2002).

An issue which remains to be clarified is whether activation of the cholinergic input to the circuitry of the DCN can have the same suppressive effect on noise-induced hyperactivity of fusiform cells as has been observed previously in normal hearing animals when the granule cells or their parallel fibers are activated (Davis et al., 1996; Davis and Young, 1997; Manis, 1989; Kanold and Young, 2001). The ability to suppress spontaneous activity in the FSL of normal hearing rats, using carbachol, an agonist of acetylcholine receptors, was first demonstrated by Zhang and Kaltenbach, (2000). It has also been shown that the sensitivity of neurons in the DCN to carbachol, is enhanced following noise exposure, both in vitro (Chang et al., 2002) and in vivo (Kaltenbach and Zhang, 2007). However, no study to date has demonstrated suppression of DCN hyperactivity by carbachol in intense sound-exposed animals.

Here, we performed an in vivo study to test the effect of carbachol on spontaneous and tone-evoked activity recorded from the FSL of the DCN of normal hearing and intense sound-exposed animals. In this study, we used hamsters, since this is a species in which hyperactivity is robust and has been shown to be particularly well-developed in the FSL (Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009). Our results show powerful effects of carbachol on FSL activity, manifest as a transient excitation followed by a more sustained reduction of activity. The nearly complete reduction of hyperactivity that was observed in exposed animals following carbachol administration suggests that cholinergic inputs to the DCN may provide a useful target for downregulation of activity leading to tinnitus.

RESULTS

For the experiments involving use of carbachol without atropine, multi-unit spontaneous firing rate (SFR) in the FSL was successfully recorded from a total of 21 animals, 10 of which were control and 11 exposed; successful recordings were obtained from an additional 6 animals in which carbachol applications were followed by atropine.

Induction of hyperactivity in the DCN

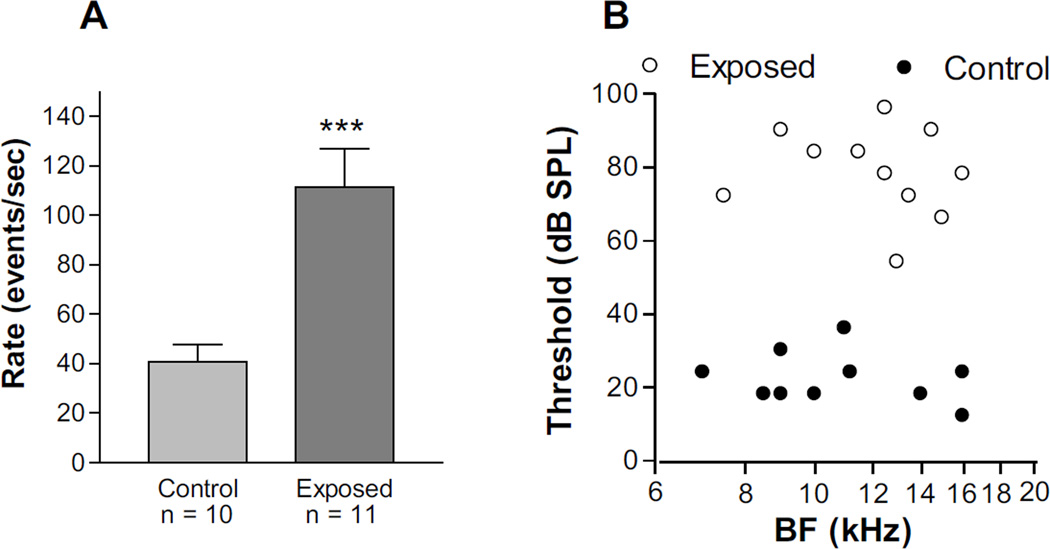

Figure 1A compares the mean spontaneous activity levels in the 7–15 kHz region of control and exposed animals. The mean level of spontaneous activity was 40 events/sec in control animals and 110 events/sec in exposed animals. This difference was highly significant (P = 0.0008; two tailed t-test) and demonstrates that the exposure tone had the effect of inducing a severe hyperactivity in the DCN, consistent with previously published studies (Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009; Manzoor et al., 2012, 2013). Sound exposure also induced large shifts in neural response thresholds (Fig. 1B). In control animals, BF thresholds were between 15 and 40 dB SPL, while in exposed animals, these ranged between 50 and 100 dB SPL. The mean BF threshold was shifted by 56 dB above the mean control level of 23 dB SPL in control animals to 79 dB SPL in exposed animals.

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean spontaneous activity (A) and BF thresholds (B) in control and intense-tone-exposed animals. All recordings were obtained from multiunit clusters in the fusiform soma layer of the 7–15 kHz region of the DCN. Each histogram bar shows the mean ± S.E.M. of spontaneous activity averaged over 90 seconds in controls (n = 10) or exposed (n = 11) animals. *** in panel A: P = 0.0008 for comparison with control group.

Effect of carbachol on spontaneous activity in control animals

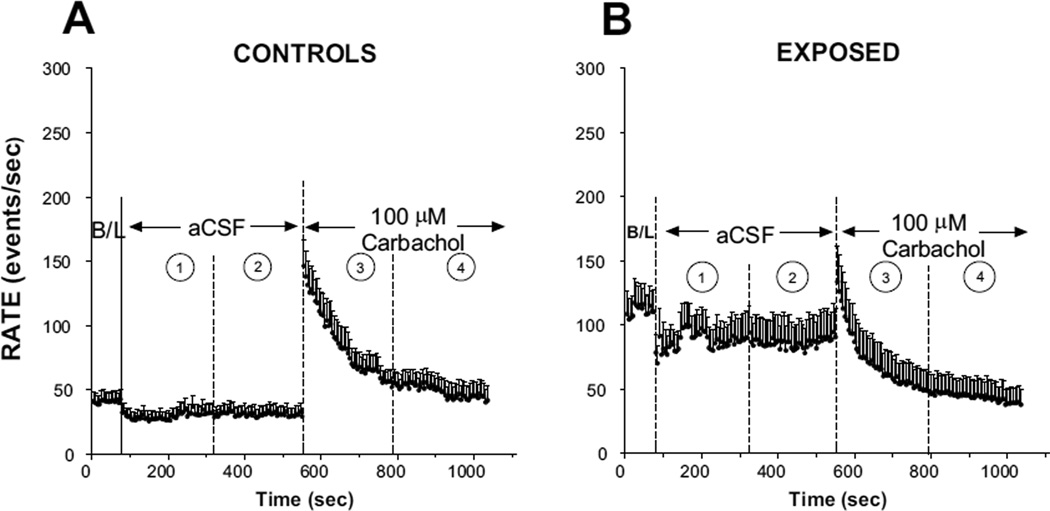

The time course of the effects of carbachol and aCSF on activity in the FSL of control animals is shown in Figure 2A. Activity in the FSL was slightly suppressed by aCSF during the 8 minute period after its application. Activity was reduced by 30% from its pre-aCSF (baseline) level during the first 4 minutes of this period (time frame 1), but then recovered to a level that was only 15% below the baseline level during the succeeding 4 minutes (time frame 2). In contrast, 100 µM carbachol had a robust excitatory effect on spontaneous activity in control animals (Fig. 2A). Firing rate averaged over the first 4 minutes of application was 142% higher than the baseline (pre-drug level) (time frame 3), a difference that was significantly higher than the corresponding change during the first 4 minutes of aCSF period (P = 0.0006, two-tailed t-test); it recovered to only 51% above baseline during the second half of the 8 minute test period (time frame 4), a difference that was not statistically significant from the average rate in the second half of the aCSF period (P = 0.095; two-tailed t-test). Thus, in control animals, carbachol had a pronounced excitatory effect on FSL spontaneous activity, resembling hyperactivity over the first half of the 8 minute test period, but this excitatory response was greatly attenuated during the second half. Similar results were obtained in animals not included in this sample, but tested with lower doses (5, 20 and 50 µM) of carbachol, although the results were weaker and less consistent across animals and thus were not studied systematically (data not shown). The general trend was toward an excitatory response with carbachol but the response magnitude varied among the animals tested.

Figure 2.

Mean time course plots showing the effects of aCSF and 100 µM carbachol on spontaneous activity in control (A) (n = 10) and exposed (B) (n = 11) animals. Each point represents the mean (+S.E.M.) of spontaneous rates averaged across the same animals on which the data in Fig. 1 are based, although the time course measures shown here were recorded later in the same experiments than those used to generated the data in Fig. 1.

Effect of carbachol on hyperactivity in exposed animals

In sound exposed animals, applications of aCSF to the DCN caused a small suppression of activity in the FSL, similar to that observed in controls, but with more variability (Fig. 2B). This suppression effect endured throughout the 8 minute post-aCSF test period. Application of aCSF caused a mean suppression of 15% below baseline during the first 4 minutes of its application (time frame 1) and 26% during the second half (time frame 2). In contrast, carbachol initially increased activity, similar to but weaker than its effect in controls (cf. time frames 3 in Fig. 2B with 2A), but this increase was followed by a decline of activity to levels that were well below both the baseline and below post-aCSF levels (time frame 4 in Fig. 2B). The firing rate averaged over the first half of the 8 minute post-carbachol test period was 38% below the pre-drug level, and that during the second half 59% below. The degree of suppression as a result of carbachol application was significantly greater than that following aCSF application (p<0.046; two tailed t-test). Moreover, there was no significant difference between the level of activity in the last 4 minutes of carbachol application (time frame 4 in Fig. 2B) and mean baseline activity recorded in controls (P = 0.85). Thus, all evidence of hyperactivity induced by sound exposure was abolished by carbachol.

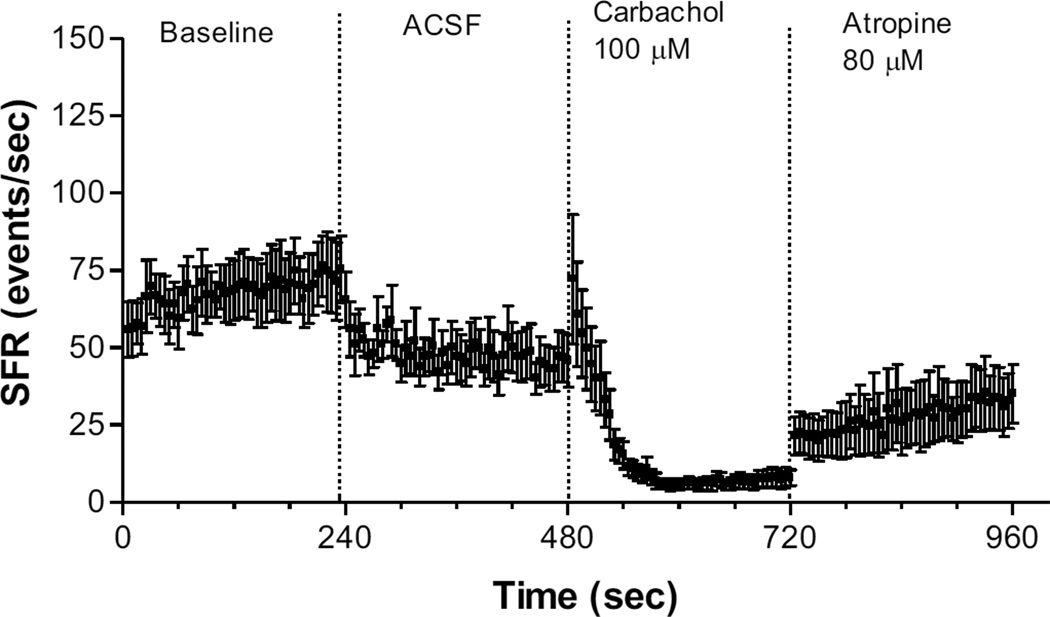

Effect of atropine on carbachol-induced suppression of hyperactivity in exposed animals

We next tested whether the suppressive effect of carbachol (100 µM) on hyperactivity in exposed animals could be reversed by atropine, a competitive muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist. The mean time course of changes in activity following carbachol and 80 µM atropine are shown in Fig. 3. Carbachol reduced spontaneous activity below baseline and below the post aCSF levels, but this decline was at least partially reversed by application of 80 µM atropine. A similar result was obtained with 40 µM atropine in 2 out of 3 trials (data not shown). These effects were not likely the result of recovery from carbachol, independent of atropine, since no such return to pre-drug baseline activity was observed when the post-carbachol time course was examined over similar periods with no atropine applied (cf. Fig. 2C with Fig. 3). Lower doses of atropine (20 µM) had little or no effect (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Mean time course plot showing effect of 80 µM atropine on spontaneous activity in the FSL of the DCN following application of aCSF and 100 µM carbachol in exposed animals. Each point represents the mean (± S.E.M.) of activity averaged across sound exposed animals (n = 6). All recordings were obtained from the 7–15 kHz region of the DCN.

Effects of carbachol on frequency tuning and BF thresholds

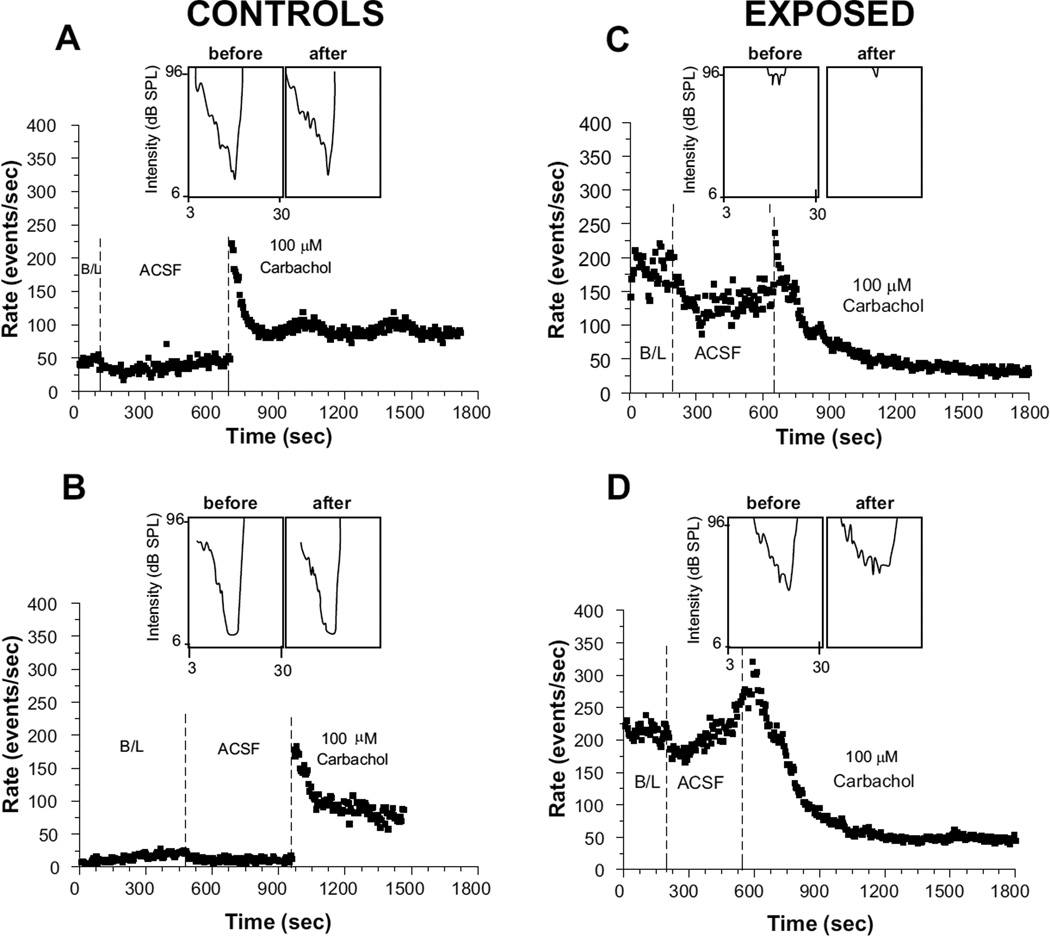

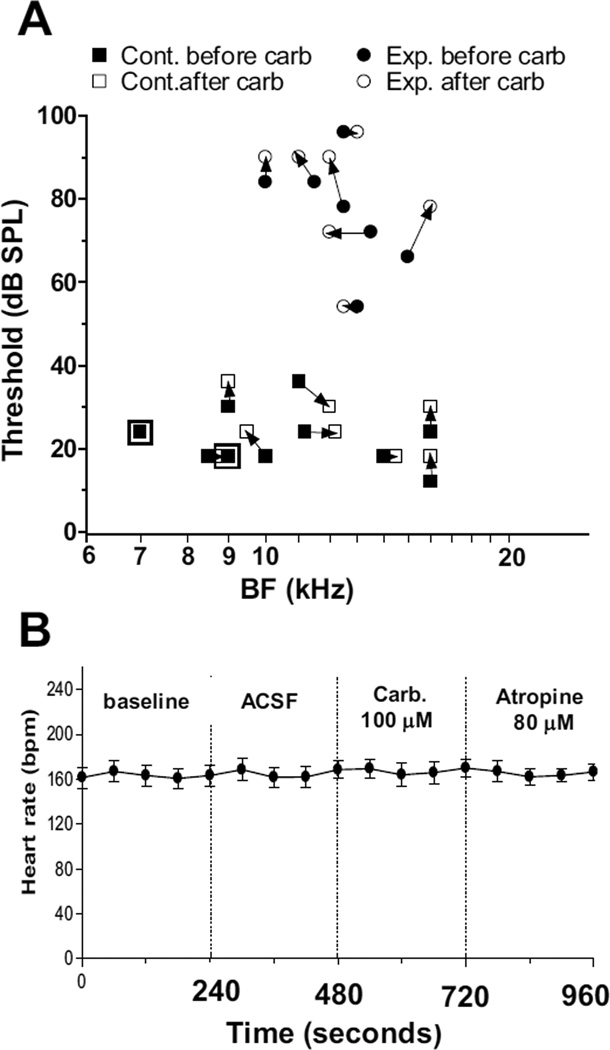

The examples shown in Fig. 4A and B illustrate the effects carbachol had on the tuning properties of FSL neurons in control animals. Of the 10 control animals tested, 6 showed the same BF threshold before and after carbachol administration, 3 showed an upward shift of 6 dB and 1 showed a decrease of 6 dB in BF threshold after carbachol (Fig. 5A). The mean threshold was 22.5 dB SPL at the beginning of the recording period and 24 dB SPL at the end of the post-carbachol period, representing a difference of only 1.5 dB, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.553). The mean BF was 11.2 kHz at the beginning of the recording session and 11.4 kHz at the end of the carbachol test period, representing a mean shift of only 0.2 kHz; this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.874). The changes in tuning following carbachol were also mostly very small in exposed animals (Fig. 5A). The mean BF threshold was 78 dB SPL at the beginning of the recording session and 81 dB SPL at the end of the post-carbachol test period, producing an average shift of only 3 dB, which was not significant (P = 0.67); the mean BF was 12.1 kHz at the beginning of the recording sessions and 12.4 kHz after carbachol, representing a change of only 0.3 kHz, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.72, two-tailed t-test). Thus, despite large decreases in spontaneous activity following 100 µM carbachol, frequency tuning and sensitivity to BF tones was only weakly affected in most exposed animals.

Figure 4.

Comparison of frequency tuning properties of FSL neurons recorded before and following application of carbachol in control (A–B) and exposed (C–D) animals. Each graph shows the time course of activity in a single animal. In each panel, the pre-carbachol tuning curve (top left of each graph) was recorded immediately preceding measurements of baseline spontaneous activity; the tuning curve after carbachol (top right of each graph) was recorded at the end of the 8 minute post-carbachol test period.

Figure 5.

(A) Comparison of BF and BF thresholds before and after 100 µM carbachol. The symbols surrounded by large squares represent points that did not change after carbachol. (B) Recordings of heart rate before and after administration of each test solution used in this study. The trace shows the mean (± S.E.M.) heart rate time courses averaged across 4 exposed animals. The graph demonstrates the high degree of stability of cardiac function throughout the period of carbachol-induced suppression of hyperactivity in the DCN FSL.

Absence of effect of carbachol on heart rate

We last tested whether carbachol’s effects on DCN activity might have been an artifact resulting from alterations in the animal’s general physiological state. Of most concern was that carbachol applied to the DCN might spread toward the obex, where it could penetrate through the floor of the IVth ventricle and activate cholinergic input to neurons in the nearby dorsal motor nucleus that project to the heart and modulate heart rate or other vital functions. We monitored the heart rate by recording the electrocardiogram (ECG) in 4 animals throughout the recording session before and after administering 100 µM carbachol and 80 µM atropine. In none of these cases was there any change in the ECG after carbachol was applied. As shown by the example in Fig. 5B, the ECG record remained remarkably stable throughout the pre- and post-carbachol and atropine test periods, and the rhythm remained constant. Since the cardiomotor center would be expected to be highly sensitive to changes in the physiological state of the medulla, it seems unlikely that the suppressive effects of carbachol were artifacts of a general effect on the brainstem.

DISCUSSION

The main goal of this study was to determine whether spontaneous activity in the hamster DCN could be modulated by application of a cholinergic agonist to the surface of the DCN, and if so, whether that modulation might be exploited to reverse hyperactivity induced by intense sound exposure. Our results clearly show that carbachol has potent effects on spontaneous activity in the hamster DCN and reveal an important contrast between those effects in control and exposed animals. We now summarize the key features of these differences and discuss the possible mechanisms that underlie them and their functional and clinical implications.

Carbachol abolished hyperactivity caused by intense sound exposure

As in previous studies, we showed that intense sound-exposed animals displayed evidence of increased spontaneous activity in the FSL (Finlayson et al., 2009; Brozoski et al., 2002; Shore et al., 2008). In the present study, we found that this hyperactivity was completely abolished by carbachol, and the suppression was strong enough to lower the levels of activity to those seen in control animals before any test solutions were applied. This suppressive effect was partially reversed by atropine, consistent with the interpretation that the effect was mediated, at least in part, by muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Similar inhibitory effects of carbachol on spontaneous activity in the FSL were observed in normal hearing rats (Zhang and Kaltenbach, 2000; Kaltenbach and Zhang, 2007), although the inhibition was usually preceded by a transient spike of excitation. In the present study, normal hearing hamsters showed an initial spike of excitation following carbachol, similar to that in the rat, but the decline of activity that followed this initial response did not completely return to the pre-drug baseline.

Carbachol had little effect on neural tuning and tip sensitivity

Overall, the impression given by our results is that the modulatory effect of carbachol on spontaneous activity occurred with only marginal effects on frequency tuning and BF thresholds. More work will be necessary to determine whether this also applies to suprathreshold sounds and more complex stimuli. These findings nevertheless reinforce previous evidence that spontaneous activity and threshold sensitivity are controlled by different mechanisms (Caspary et al., 1983; Kaltenbach et al., 1998; Brozoski et al., 2002; Manzoor et al., 2012).

Mechanisms mediating the inhibitory effect of carbachol in exposed animals

The time course of carbachol’s effects on activity in exposed animals was similar to that in controls in showing an initial spike of activation followed by a decline of activity to a plateau level. Despite these similarities, two important features distinguish the time course of carbachol’s effects in exposed and control animals. One is that the inhibitory effect had a steeper slope with activity declining more sharply in exposed animals than in controls (cf. Fig. 2A and 2B). In addition, the post-carbachol level of activity reached a plateau at a level that was between one-third and one-half of the activity level recorded before drug application; in contrast, the activity recovered to a plateau level that was still above the pre-drug level of activity in control animals. These differences suggest that the circuit was modified in some way that favored an increase in the strength and speed of inhibition following sound exposure.

Insight into the mechanism of the inhibitory effect in exposed animals requires information about how the receptors are distributed across cell populations and how that distribution is altered by sound exposure. Although these details were not the focus of the present study, previous work from our group has shown that noise exposure results in an increase in the expression of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), the enzyme of acetylcholine synthesis, in the cochlear nucleus as early as 8 days postexposure (Jin and Godfrey, 2006). These increases were found in cochlear nucleus regions that receive input from the cholinergic olivocochlear bundle and were found to endure for up to at least 5 months after exposure (Godfrey et al., 2013). The increased strength of inhibition observed in our recordings from the FSL of sound exposed animals is consistent with an increase in the inhibition of fusiform cells via the granule cell-cartwheel cell, which may reflect the upregulation of sensitivity to cholinergic input from the olivocochlear bundle.

Another possible mechanism

An alternative explanation of carbachol’s modulation of DCN activity is that it is part of a non-specific effect on the brainstem or on vital functions that would influence not only auditory nuclei but other nuclei in the brainstem with cholinergic sensitivity. Several findings argue against this interpretation. First, our recordings of the ECG demonstrated a constant heart rate and normal rhythm throughout the pre- and post-drug application periods (Fig. 5B). The fact that heart rate remained constant throughout the pre- and post-carbachol recording periods is a strong indicator that vital functions were not significantly altered by our carbachol applications. In addition, the fact that carbachol had different effects in exposed and control animals indicates that the alteration of activity caused by carbachol was specifically auditory in nature and likely related to alterations of the cochlear nucleus, rather than to alterations of non-auditory areas of the brain. Finally, unlike carbachol’s dramatic effect on spontaneous activity, its effect on tuning or tip thresholds was minimal. This is inconsistent with a global or generalized change in activity caused by carbachol’s actions on non-specific targets, which would have been expected to cause upward shifts in BF thresholds. Taken together, these results are most consistent with a direct effect of carbachol on the circuitry of the DCN that is independent of inputs from outside the cochlear nucleus and not indicative of changes in the general physiological state of the animals.

Implications

It is interesting that several recent studies have concluded that stimulation of the vagus nerve, which is cholinergic, can have an ameliorative effect on tinnitus. Vagus nerve activation has been found to abolish tinnitus in animal models (Engineer et al., 2011; 2013). The mechanism of vagally-induced suppression of tinnitus is unknown, but it may involve modulation of hyperactive auditory centers. Our results are consistent with this hypothesis and provide a proof of concept that cholinergic activation has a suppressive effect on hyperactivity in a brain center that has been implicated in tinnitus generation. Future studies examining the effect of vagal nerve activation on DCN hyperactivity may reveal a link between the effect of vagal nerve stimulation on tinnitus and those observe here.

Our results demonstrate that, in principal, it is possible to pharmacologically suppress noise-induced hyperactivity in the DCN by drug application to the DCN surface. Because hyperactivity is widely believed to be a neural correlate of tinnitus, it is implicit in this result that abolishing hyperactivity may be a key strategy for abolishing tinnitus. A key question that remains to be addressed is whether the same drug application that abolishes noise-induced hyperactivity in the DCN also abolishes similar hyperactivities at more rostral levels of the auditory system, such as the inferior colliculus or auditory cortex. Based on our recent work showing that ablation of the DCN abolishes noise-induced hyperactivity in the contralateral IC (Manzoor et al., 2012), we can predict that abolishing hyperactivity in the DCN output pathway from the FSL using cholinergic agonists would have a similar effect. We do not know if this would also abolish tinnitus-related hyperactivity at the cortical level, but future experiments addressing this question would be of considerable value. Our results also provide additional evidence that the pathways controlling spontaneous activity and tone-elicited responses of fusiform cells are separate and independent. We found that although suppression of hyperactivity was clearly achieved with carbachol application, the sensitivities of neurons to sound (i.e., their BF thresholds) were unaffected. This suggests that, in theory, it may be possible to devise methods to suppress tinnitus, via activation of the cholinergic system, without worsening hearing thresholds.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animal subjects

Adult male Syrian golden hamsters were acquired from Charles River Laboratory and housed in the animal vivarium of the Lerner Research Institute on a 12 hr:12 hr light:dark cycle. All procedures performed were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cleveland Clinic, which adheres to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Median age of all animals at the time of experiments was 111 days (range: 60–160 days). Animals were divided into two groups with one group exposed to intense sound and the other group serving as controls. Animals were studied electrophysiologically between 2 and 8 weeks post-exposure.

Sound Exposure

Animals were exposed to intense sound inside an acrylic chamber placed inside a sound attenuation booth as described in previous publications (Manzoor et al., 2012, 2013). The exposure sound was a continuous 10 kHz pure tone presented from the lid of the chamber using a 6 inch diameter speaker. The output of the speaker was adjusted so that the intensity of the sound at the animals’ ears was 115 dB SPL ± 6 dB SPL. The sound was maintained at this level for a period of 4 hours. At the end of the exposure, each animal was tagged subcutaneously with an identification chip and returned to the vivarium for a period of 2–8 weeks until the time of electrophysiological recordings.

Surgical preparation, electrophysiology and drug preparation and application

These procedures were similar to those described previously (Kaltenbach and Zhang, 2007; Manzoor et al., 2012, 2013), and will be summarized only briefly here. Following the 2–8 week postexposure recovery time, sound-exposed and age-matched controls were anesthetized using intramuscular injection of ketamine/xylazine (117/18 mg/kg). A tracheotomy and craniotomy were performed, and the left DCN was exposed. A CT-1000 cardio-tachometer was used to monitor the heart rate and the EKG waveform throughout the electrophysiological recording session. Extracellular multi-unit recordings were performed using glass pipette electrodes (0.4–0.5 MΩ). Measures of frequency response areas and spontaneous activity were performed in the FSL of the DCN (150–200 µm below the DCN surface). Frequency response areas were obtained to document the best frequency (BF) of the cluster of neurons under study and any changes in thresholds induced by sound exposure and drug application. Recordings of spontaneous activity were performed in the 7–15 kHz region of the DCN, as this is the range in which hyperactivity reaches its maximal levels after the 10 kHz sound exposure (Finlayson and Kaltenbach, 2009; Manzoor et al., 2013). In each animal, a pre-drug frequency response area was recorded. This was followed immediately by recordings of baseline spontaneous activity for several minutes, then recordings of spontaneous activity for 8 minutes following administration of artifical cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), then after administration of the primary test agent (carbachol); in some experiments, carbachol application was followed by application of the muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine. The concentrations of drugs were varied in preliminary studies, and after much experimentation, it was determined that the lowest doses that yielded the most consistent effects across animals were 100 µM carbachol and 80 µM atropine. Measures of spontaneous rate were obtained by counting the number of spontaneous events in a succession of 5 second epochs that spanned the period of observation. These counts were converted to rate (expressed in events/second) by dividing the count by 5. After recordings of spontaneous activity were completed at a given locus, a frequency response area was again obtained to document any change in BF or BF threshold that might have resulted from administration of the test solution.

Drug preparation and application

ACSF is a balanced isotonic salt solution consisting of (in mM) 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 0.1 CaCl2.2H2O, 3.2 MgCl2.6H2O, 26 NaHCO3 and 10 mM glucose. The stock was diluted in aCSF to yield final concentrations of 10–100 µM. Similarly, atropine (Sigma) was prepared in aCSF to yield final concentrations of 20–80 µM. All solutions on the experiment day were heated to 37°C using a water bath outside the recording chamber. While the electrode was still in the subsurface recording position, solutions were applied using a micro-drip method by using a 1 cc syringe with a 27 gauge needle tip. Two drops of solution were adequate to uniformly cover the surface of the DCN with no visible spread of fluid to regions outside the borders of the DCN. Only one data set was recorded from each animal to eliminate the possibility of drug sensitization in subsequent recordings. The solution, once applied, dispersed and spread over the DCN surface without formation of any liquid meniscus.

Data analysis

Each experiment yielded a time course plot of spontaneous firing rate (events/sec) versus time (seconds) for the various test conditions for a single animal. Mean plots for each test condition (baseline, aCSF or carbachol) for each group (exposed or controls) were obtained by averaging the time course plots across animals. Frequency tuning curves were used to ascertain the best frequency (BF) of the neurons at each recording location. Effects of aCSF, atropine and carbachol on spontaneous activity in the FSL were quantified by subtracting the mean firing rate during aCSF or drug period from the mean firing rate in the pre-aCSF or drug period and dividing the result by the mean firing rate in the pre-aCSF or drug period. Tests of significance were conducted using paired and un-paired t-tests for 2 groups when applicable; differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Research Highlights.

We studied effects of carbachol on spontaneous activity in the fusiform soma layer (FSL) of the DCN.

Intense tone exposure caused major increases in FSL spontaneous activity

Admistration of carbachol at a dose of 100 µM, increased spontaneous activity in controls animals.

The same dose of carbachol, however, resulted in suppression of hyperactivity in exposed animals.

The cholinergic system may represent a possible new drug target for the treatment of tinnitus.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Donald A. Godfrey in the Departments of Neurology and Surgery at the University of Toledo College of Medicine for his critical reading of the manuscript and his many helpful comments. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 DC009097.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adams JC. Ascending projections to the inferior colliculus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979;183:519–538. doi: 10.1002/cne.901830305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JC, Warr WB. Origins of axons in the cat’s acoustic striae determined by injection of horseradish peroxidase into severed tracts. J. Comp. Neurol. 1976;170:107–121. doi: 10.1002/cne.901700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson TE, Brown MC. Synapses formed by olivocochlear axon branches in the mouse cochlear nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;295:52–70. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Bauer CA, Caspary DM. Elevated fusiform cell activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of chinchillas with psychophysical evidence of tinnitus. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:2383–2390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02383.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, Wisner KW, Sybert LT, Bauer CA. Bilateral dorsal cochlear nucleus lesions prevent acoustic-trauma induced tinnitus in an animal model. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2012;13:55–66. doi: 10.1007/s10162-011-0290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Havey DC, Faingold CL. Effects of acetylcholine on cochlear nucleus neurons. Exp. Neurol. 1983;82:491–498. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(83)90419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Hughes LF, Schatteman TA, Turner JG. Age-related changes in the response properties of cartwheel cells in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 2006:216–217–207- 215. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Chen K, Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J, Godfrey DA. Effects of acoustic trauma on dorsal cochlear nucleus neuron activity in slices. Hear. Res. 2002;164:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G-D, Jastreboff PJ. Salicylate-induced abnormal activity in the inferior colliculus of rats. Hear. Res. 1995;82:158–178. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00174-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Waller HJ, Godfrey DA. Cholinergic modulation of spontaneous activity in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 1994;77:168–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Waller HJ, Godfrey DA. Effects of endogenous acetylcholine on spontaneous activity in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus slices. Brain. Res. 1998;783:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Waller HJ, Godfrey TG, Godfrey DA. Glutamergic transmission of neuronal responses to carbachol in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus slices. Neuroscience. 1999;90:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00503-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, Powley TL, Schwaber JS, Doyle FJ3rd. Projections of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus to cardiac ganglia of rat atria: an anterograde tracing study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999;410:320–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA, Miller RL, Young ED. Effects of somatosensory and parallel-fiber stimulation on neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3012–3024. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KA, Young ED. Granule cell activation of complex-spiking neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6798–6806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06798.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Mulders WH, Rodger J, Woo S, Robertson D. Acoustic trauma evokes hyperactivity and changes in gene expression in guinea-pig auditory brainstem. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010 May;31(9):1616–1628. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer ND, Riley JR, Seale JD, Vrana WA, Shetake JA, Sudanagunta SP, Borland MS, Kilgard MP. Reversing pathological neural activity using targeted plasticity. Nature. 2011;470:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engineer ND, Møller AR, Kilgard MP. Directing neural plasticity to understand and treat tinnitus. Hear. Res. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson PG, Kaltenbach JA. Alterations in the spontaneous discharge patterns of single units in the dorsal cochlear nucleus following intense sound exposure. Hear. Res. 2009;256:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis GS, Wurster RD. Horseradish peroxidase localization of cardiac vagal preganglionic somata. Brain. Res. 1980a;182:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90827-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geis GS, Wurster RD. Cardiac responses during stimulation of the dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus ambiguus in the cat. Circ. Res. 1980b;46:606–611. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, DAPark JL, Ross CD. Choline acetyltransferase and acetylcholinesterase in centrifugal labyrinthine bundles of rats. Hear. Res. 1984;14:93–106. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(84)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Godfrey TG, Mikesell NL, Waller HJ, Yao W, Chen K, Kaltenbach JA. In: Chemistry of granular and closely related regions of the cochlear nucleus. Syka J, editor. New York: Acoustical Signal Processing in the Central Auditory System Plenum; 1997. pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Park-Hellendall JL, Dunn JD, Ross CD. Effects of trapezoid body and superior olive lesions on choline acetyltransferase activity in the rat cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 1987a;28:253–270. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Park-Hellendall JL, Dunn JD, Ross CD. Effect of olivocochlear bundle transection on choline acetyltransferase activity in the rat cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 1987b;28:237–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DA, Beranek KL, Carlson L, Parli JA, Dunn JD, Ross CD. Contribution of centrifugal innervation to choline acetyltransferase activity in the cat cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 1990;49:259–279. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JW, Halpin CF, Nam EC, Levine RA, Melcher JR. Tinnitus, diminished sound-level tolerance, and elevated auditory activity in humans with clinically normal hearing sensitivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;104:3361–3370. doi: 10.1152/jn.00226.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtu S, Sharma DK, Pant KK, Sinha JN, Bhargava KP. Role of medullary cholinoceptors in baroreflex bradycardia. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 1986;A 8:1063–1079. doi: 10.3109/10641968609044086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Sasaki CT. Salicylate-induced changes in spontaneous activity of single units in the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1986;80:1384–1391. doi: 10.1121/1.394391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastreboff PJ, Brennan JF, Coleman JK, Sasaki CT. Phantom auditory sensation in rats, an animal model for tinnitus. Behav. Neurosci. 1988;102:811–822. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.6.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YM, Godfrey DA, Sun Y. Effects of cochlear ablation on choline acetyltransferase activity in the rat cochlear nucleus and superior olive. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005;81:91–101. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YM, Godfrey DA. Effects of cochlear ablation on muscarinic acetylcholine receptor binding in the rat cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006;83:157–166. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YM, Godfrey DA, Wang J, Kaltenbach JA. Effects of intense tone exposure on choline acetyltransferase activity in the hamster cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 2006;216–217:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Godfrey DA, Neumann JB, McCaslin DL, Afman CE, Zhang J. Changes in spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus following exposure to intense sound, Relation to threshold shift. Hear. Res. 1998;124:78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J, Afman CE. Plasticity of spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure. Hear. Res. 2000;147:282–292. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00138-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Rachel JD, Mathog TA, Zhang JS, Falzarano PR, Lewandowski M. Cisplatin induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and its relation to outer hair cell loss, Relevance to tinnitus. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:699–714. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, McCaslin D. Increases in spontaneous activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus following exposure to high intensity sound, A possible neural correlate of tinnitus. Auditory. Neurosci. 1996;3:57–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Afman CE. Hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure and its resemblance to tone-evoked activity, a physiological model for tinnitus. Hear. Res. 2000;140:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zacharek MA, Zhang JS, Frederick S. Activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of hamsters previously tested for tinnitus following intense tone exposure. Neurosci. Let. 2004;355:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zhang J. Intense sound-induced plasticity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of rats: evidence for cholinergic receptor upregulation. Hear. Res. 2007;226:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane EC. Patterns of degeneration in the caudal cochlear nucleus of the cat after cochlear ablation. Anat. Rec. 1974;179:67–92. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091790106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanold PO, Young ED. Proprioceptive information from the pinna provides somatosensory input to cat dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:7848–7858. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07848.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya H, Eggermont JJ. Spontaneous firing activity of cortical neurons in adult cats with reorganized tonotopic map following pure-tone trauma. Acta. Otolaryngol. 2000;120:750–756. doi: 10.1080/000164800750000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszeghy Á, Vincze J, Rusznák Z, Fu Y, Paxinos G, Csernoch L, Szücs G. Activation of muscarinic receptors increases the activity of the granuleneurones of the rat dorsal cochlear nucleus--a calcium imaging study. Pflugers. Arch. 2012;463:829–844. doi: 10.1007/s00424-012-1103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanting CP, de Kleine E, van Dijk P. Neural activity underlying tinnitusgeneration: results from PET and fMRI. Hear. Res. 2009;255:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licari FG, Shkoukani M, Kaltenbach JA. Stimulus-dependent changes in optical responses of the dorsal cochlear nucleus using voltage-sensitive dye. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;106:421–436. doi: 10.1152/jn.00982.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood AH, Wack DS, Burkard RF, Coad ML, Reyes SA, Arnold SA, Salvi RJ. The functional anatomy of gaze-evoked tinnitus and sustained lateral gaze. Neurology. 2001;56:472–480. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe Y, Saito T, Saito H. Effects of lidocaine on salicylate-induced discharges of neurons in the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig. Hear. Res. 1997;103:192–198. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manis PB. Responses to parallel fiber stimulation in the guinea pig dorsal cochlear nucleus in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 1989;61:149–161. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manis PB, Spirou GA, Wright DD, Paydar S, Ryugo DK. Physiology and morphology of complex spiking neurons in the guinea pig dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994;348:261–276. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor NF, Licari FG, Klapchar M, Elkin RL, Gao Y, Chen G, Kaltenbach JA. Noise-induced hyperactivity in the inferior colliculus: its relationship with hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;108:976–988. doi: 10.1152/jn.00833.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor NF, Gao Y, Licari F, Kaltenbach JA. Comparison and contrast of noise-induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and inferior colliculus. Hear. Res. 2013;295:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamed SB, Kaltenbach JA, Church MW, Burgio DL, Afman CE. Cisplatin-induced increases in spontaneous neural activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and associated outer hair cell loss. Audiology. 2000;39:24–29. doi: 10.3109/00206090009073051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher JR, Sigalovsky IS, Guinan JJ, Jr, Levine RA. Lateralized tinnitus studied with functional magnetic resonance imaging: abnormal inferior colliculus activation. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;83:1058–1072. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.2.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellott JG, Motts SD, Schofield BR. Multiple origins of cholinergic innervation of the cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience. 2011;180:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli MO, Malsbury CW. Brainstem origins and projections of the cervical and abdominal vagus in the golden hamster: a horseradish peroxidase study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;237:65–76. doi: 10.1002/cne.902370105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JW, Kiritani T, Pedersen C, Turner JG, Shepherd GM, Tzounopoulos T. Mice with behavioral evidence of tinnitus exhibit dorsal cochlear nucleus hyperactivity because of decreased GABAergic inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:7601–7606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100223108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JW, Tzounopoulos T. Imaging the neural correlates of tinnitus: a comparison between animal models and human studies. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2012:6–35. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP, Wood RI. Stereotaxic atlas of the golden hamster brain. New York, N.Y.: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK. In: Cholinergic, GABA-ergic, and noradrenergic input to cochlear granule cells in the guinea pig and monkey. Syka J, Masterton RB, editors. Plenum, New York: Auditory pathway: structure and function; 1988. pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mulders WH, Robertson D. Hyperactivity in the auditory midbrain after acoustic trauma, dependence on cochlear activity. Neuroscience. 2009;164:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders WH, Robertson D. Progressive centralization of midbrain hyperactivity after acoustic trauma. Neuroscience. 2011;192:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norena AJ, Eggermont JJ. Changes in spontaneous neural activity immediately after an acoustic trauma, implications for neural correlates of tinnitus. Hear. Res. 2003;183:137–153. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noreña AJ, Eggermont JJ. Enriched acoustic environment after noise trauma abolishes neural signs of tinnitus. Neuroreport. 2006;17:559–563. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200604240-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosaka S, Tamamoto T, Yasunaga K. Localization of vagal cardioinhibitory preganglionic neurons within rat brain stem. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979;186:79–92. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi K, Eggermont JJ. Effects of quinine on neural activity in cat primary auditory cortex. Hear. Res. 1997;105:105–118. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver DL. Dorsal cochlear nucleus projections to the inferior colliculus in the cat: a light and electron microscopic study. J. Comp. Neurol. 1884;224:155–172. doi: 10.1002/cne.902240202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen KK, Mugnaini E, Dahl AL, Christiansen AH. Histochemical localization of acetylcholinesterase in the cochlear and superior olivary nuclei. A reappraisal with emphasis on the cochlear granule cell system. Arch. Ital. Biol. 1984;122:169–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen KK. Projection of the cochlear nuclei onthe inferior colliculus in the cat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1972;144:355–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.901440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pál B, Koszeghy A, Pap P, Bakondi G, Pocsai K, Szucs G, Rusznák Z. Targets, receptors and effects of muscarinic neuromodulation on giant neurones of the rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;30:769–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham K, Kim DO. Spontaneous and sound-evoked discharge characteristics of complex-spiking neurons in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the unanesthetized decerebrate cat. J. Neurophysiol. 1995;73:550–561. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham K, Bonaiuto G, Carlson S, Turner JG, D’Angelo WR, Bross LS, Fox A, Willott JF, Kim DO. Purkinje cell degeneration and control mice: responses of single units in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and the acoustic startle response. Hear. Res. 2000;148:137–152. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portfors CV, Roberts PD. Temporal and frequency characteristics of cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the awake mouse. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:744–756. doi: 10.1152/jn.01356.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachel JD, Kaltenbach JA, Janisse J. Increases in spontaneous neural activity in the hamster dorsal cochlear nucleus following cisplatin treatment: a possible basis for cisplatin-induced tinnitus. Hear. Res. 2002;164:206–214. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00287-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen GL. Efferent connections of the cochlar nucleus. In: Graham AB, editor. Sensorineural Hearing Processes and Disorders. Boston: Little, Brown and Co; 1967. pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Bester C, Vogler D, Mulders WH. Spontaneous hyperactivity in the auditory midbrain: Relationship to afferent input. Hear. Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.02.002. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Motts SD, Mellott JG. Cholinergic cells of the pontomesencephalic tegmentum: connections with auditory structures from cochlear nucleus to cortex. Hear. Res. 2011;279:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwaber JS, Cohen DH. Field potential and single unit analyses of the avian dorsal motor nucleusof the vagus and citeria for identifying vagal cardiac cells of origin. Brain. Res. 1978;147:79–90. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki S, Eggermont JJ. Changes in spontaneous firing rate and neural synchrony in cat primary auditory cortex after localized tone-induced hearing loss. Hear. Res. 2003;180:28–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherriff FE, Henderson Z. Cholinergic neurons in the ventral trapezoid nucleus project to the cochlear nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;58:627–633. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, Moore JK. Sources of input to the cochlear granule cell region in the guinea pig. Hear. Res. 1998;116:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00207-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SE, Koehler S, Oldakowski M, Hughes LF, Syed S. Dorsal cochlear nucleus responses to somatosensory stimulation are enhanced after noise-induced hearing loss. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008;27:155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gendt MJ, Boyen K, de Kleine E, Langers DRM, van Dijk P. The Relation between Perception and Brain Activity in Gaze-Evoked Tinnitus. J. Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2791-12.2012. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler DP, Robertson D, Mulders WH. Hyperactivity in the ventral cochlear nucleus after cochlear trauma. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:6639–6645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6538-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller HJ, Godfrey DA. Functional characteristics of spontaneously active neurons in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;71:467–478. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller HJ, Godfrey DA, Chen K. Effects of parallel fiber stimulation on neurons of rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear. Res. 1996;98:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warr B. In: Organization of olivocochlear efferent systems in mammals, in Handbook of Auditory Research. Webster Douglas B, Popper Arthur N, Fay Richard R., editors. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 410–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Oertel D. Cartwheel and superficial stellate cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus of mice: intracellular recordings in slices. J. Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1384–1397. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.5.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Kaltenbach JA. Modulation of spontaneous activity by acetylcholine receptors in the rat dorsal cochlear nucleus in vivo. Hear. Res. 2000;140:7–17. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Kaltenbach JA. Incrases in spontaneous activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the rat following exposure to high intensity sound. Neurosci. Let. 1998;250:197–200. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Lu YX, Yao H, Owyang C. Spatial organization of neurons in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus synapsing with intragastric cholinergic and nitric oxide/VIP neurons in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver. Physiol. 2008;294:G1201–G1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00309.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]