Abstract

Organisms are constantly challenged by stresses and privations and require adaptive responses for their survival. The transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO is central nexus in these responses, but despite its importance little is known about how it regulates its target genes. Proteomic identification of DAF-16/FOXO binding partners in Caenorhabditis elegans and their subsequent functional evaluation by RNA interference (RNAi) revealed several candidate DAF-16/FOXO cofactors, most notably the chromatin remodeller SWI/SNF. DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF form a complex and globally colocalize at DAF-16/FOXO target promoters. We show that specifically for gene-activation, DAF-16/FOXO depends on SWI/SNF, facilitating SWI/SNF recruitment to target promoters, in order to activate transcription by presumed remodelling of local chromatin. For the animal, this translates into an essential role of SWI/SNF for DAF-16/FOXO-mediated processes, i.e. dauer formation, stress resistance, and the promotion of longevity. Thus we give insight into the mechanisms of DAF-16/FOXO-mediated transcriptional regulation and establish a critical link between ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling and lifespan regulation.

Keywords: daf-16, FOXO, SWI/SNF, longevity, stress response, dauer formation, chromatin remodelling, proteomics

Introduction

The ability to adapt to stresses and privations is crucial for the survival and thus the longevity of any species. Sophisticated mechanisms are in place to perceive such dire conditions and relay them into the appropriate responses, i.e. cytoprotective and homeostatic measures and sometimes even a reversible cessation of development or reproduction1. A core pathway for these responses in animals is the environmentally responsive insulin-like signalling pathway with its conserved downstream component, the forkhead transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO2. In the presence of ample food and optimal conditions, high insulin-like signalling inactivates DAF-16/FOXO via AKT kinase-mediated phosphorylation, causing cytoplasmic sequestration of DAF-16/FOXO by 14-3-3 proteins. Conversely, upon dire conditions, i.e. cues that reduce insulin-like signalling and thus allow for reversal of DAF-16/FOXO phosphorylation, sequestration is alleviated, enabling DAF-16/FOXO to translocate to the nucleus, where it engages in transcriptional regulation. Several hundred DAF-16/FOXO target genes have been identified, and it is their concerted action that confers a wide range of beneficial effects upon the organism – most notably stress resistance and longevity, but also metabolic responses, stem cell maintenance, and tumour suppression3,4. Although many studies have explored the signalling pathways leading to DAF-16/FOXO activation, little is known about the mechanisms or cofactors by which DAF-16/FOXO regulates its target genes.

Results

Identification of candidate DAF-16/FOXO cofactors

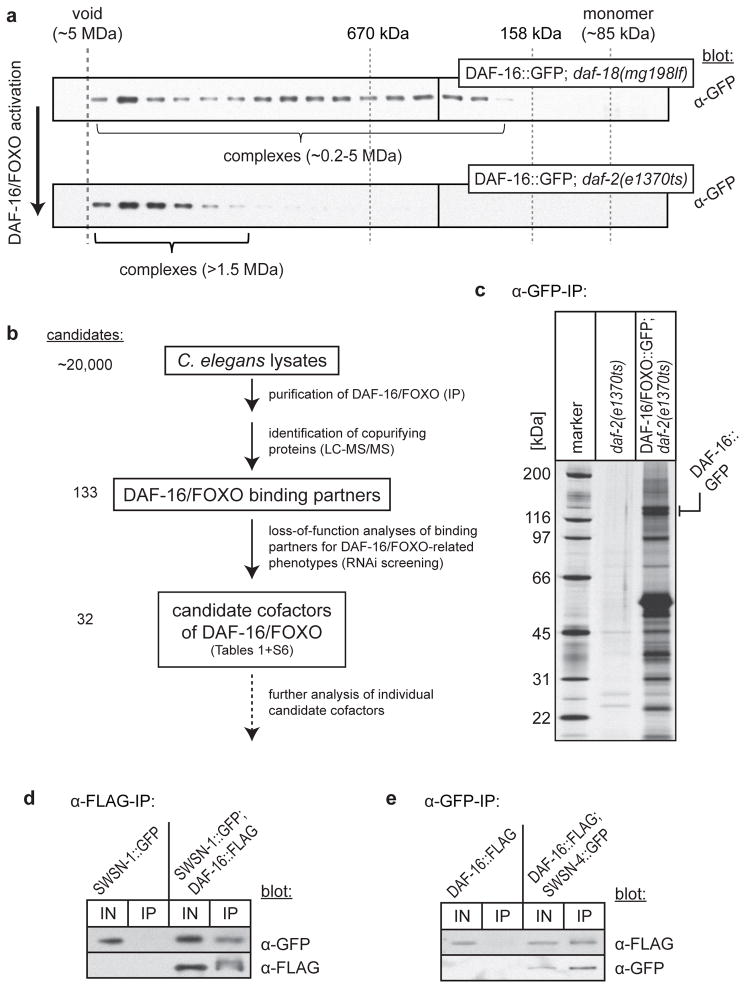

To address this problem we used the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a model system that has been instrumental in dissecting the functions of DAF-16/FOXO, mostly due to its amenability for genetic manipulation and its compatibility with high-throughput screening approaches for developmental arrest, stress resistance and lifespan phenotypes. We biochemically characterized DAF-16/FOXO by size exclusion chromatography of whole C. elegans lysates, which revealed that a significant amount of DAF-16/FOXO partitions to high molecular weight fractions (Fig. 1a). Activation of DAF-16/FOXO in a daf-2/insulin-like growth factor mutant background increased the partitioning of DAF-16/FOXO to these fractions (Fig. 1a), suggesting that DAF-16/FOXO activity involves and maybe even requires binding to other proteins, i.e. cofactors. Hence we conducted a screen to identify cofactors of DAF-16/FOXO, in which we combined proteomic identification of DAF-16/FOXO binding partners with high-throughput functional assays using RNA interference (RNAi) (Fig. 1b). Epitope-tagged DAF-16/FOXO was immunoprecipitated in different states of activation, using three different C. elegans genetic backgrounds: wild-type (DAF-16 partially active), daf-2(e1370ts) at restrictive temperature (insulin/IGF receptor mutant; DAF-16 fully active), or daf-18(mg198lf) (PTEN mutant, causing constitutively high PIP3 signalling which in turn constitutively activates the AKT kinases that phosphorylate and inactivate DAF-16/FOXO; DAF-16 inactive). Proteins that specifically co-purified with DAF-16/FOXO were identified by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; see also Fig. 1c). In addition to previously known DAF-16/FOXO binding partners (i.e. the 14-3-3 proteins FTT-2 and PAR-55), we identified 131 new binding partners of DAF-16/FOXO, the majority of which were enriched in purifications of active DAF-16/FOXO (Table S1).

Figure 1.

DAF-16/FOXO binds to the chromatin remodeller SWI/SNF. (a) C. elegans strains yielding inactive cytoplasmic DAF-16/FOXO (daf-18(mg198lf)/PTEN) or active nuclear DAF-16/FOXO (daf-2(e1370ts)/insulin-IGF receptor) were shifted for 20 h to restrictive temperature, lysed and lysates separated on a Superose 6 size-exclusion column. Fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. (b) Schematics of the screen for DAF-16/FOXO cofactors. (c) SDS-PAGE/silver stain analysis of large-scale α-GFP immunoprecipitations from indicated strains. (d,e) Confirmatory co-IPs. DAF-16/FOXO::FLAG (d) or SWSN-4/BRG1::GFP (e) were immunoprecipitated from whole-worm lysates of the indicated strains. 50 U/ml Benzonase was added to eliminate DNA- or RNA-mediated interactions. Samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting. For some inputs only fractions were loaded: 2% for SWSN-1::GFP (d), 2% for DAF-16::FLAG (e), and 20% for SWSN-4::GFP (e).

To identify potential DAF-16/FOXO cofactors amongst these binding partners, we silenced their expression by RNAi and examined a range of aging and gene expression phenotypes expected from altered DAF-16/FOXO activity: To identify cofactors required for DAF-16/FOXO activity, we tested each gene inactivation for impaired DAF-16/FOXO-induced lifespan extension or an inability to up-regulate the DAF-16/FOXO-activated gene sod-3 in daf-2 mutant animals (Tables 1, S2, S3). To identify interacting proteins that antagonize DAF-16/FOXO activity, we tested each gene inactivation for an extension of lifespan or inappropriate induction of sod-3 in otherwise wild-type animals (Tables S4–S6). Out of 72 DAF-16/FOXO binding partners tested, inactivation of the genes encoding 32 of them caused significant phenotypes in at least one of the assays. Thus they were considered candidate cofactors of DAF-16/FOXO (Tables 1, S6). Comparison of the frequency of phenotypes in Table S2 with a similar genome-wide survey6 indicated that our list of binding partners was more than 20-fold enriched for proteins involved in DAF-16/FOXO function, underscoring the utility of this co-purification approach. Many of the 32 candidate cofactors act in the regulation of chromatin and transcription (e.g. SWSN-1, SWSN-3, BAF-1, ELB-1, DCP-66, DPY-30, ZFP-1, MRG-1) or protein folding/homeostasis (e.g. RPN-9, RPN-12, CCT-8, PFD-6, PFD-2) (Tables 1, S6), both of which are important for stress response and lifespan regulation7,8. And some of the candidate cofactors even emerged from previous aging-related studies, e.g. BAF-1 controls age-dependent muscle integrity9 and CCT-8 is a component of the lifespan-regulatory cytosolic chaperonin T complex10.

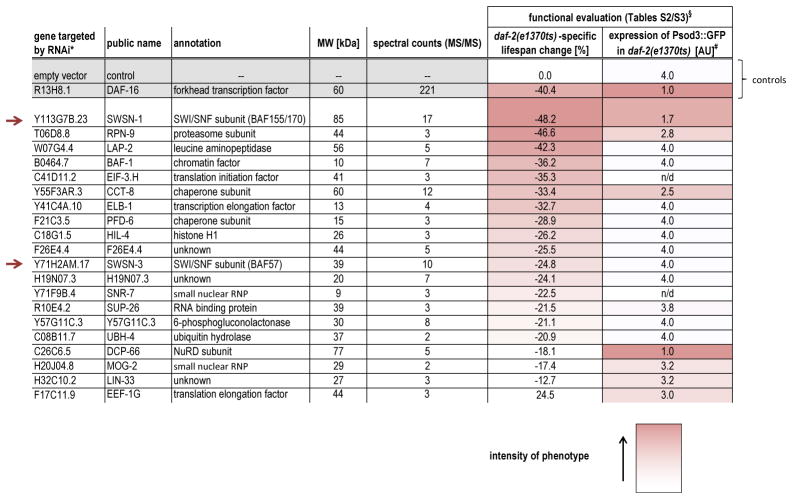

Table 1.

Short-list of candidate DAF-16/FOXO cofactors required for DAF-16/FOXO function. Table was sorted by the intensity of the lifespan phenotypes. For the full list of functional evaluation data see Tables S2–S6.

|

For rpn-9, baf-1 and cct-8 several RNAi clones were tested and the results were averaged for this table.

For a description of the GFP expression scoring scale see table S3.

Intensity of the red color denotes the intensitiy of the phenotype.

SWI/SNF binds to and colocalizes with DAF-16/FOXO

While follow-up of several of these candidate cofactors may yield compelling insight into DAF-16/FOXO mechanism and function, we focused on a candidate with particularly strong phenotypes in both, regulation of lifespan and expression of sod-3: SWSN-1 (ortholog of human BAF155/170), a core subunit of the chromatin remodeller SWI/SNF. Two additional SWI/SNF subunits, SWSN-3 (ortholog of human BAF57) and SWSN-8 (ortholog of human OSA/BAF250), were amongst our 32 candidate cofactors or at least emerged from the proteomic analysis (Tables 1, S1).

SWI/SNF is an essential 1–2 MDa multi-subunit complex that repositions, exchanges, or displaces nucleosomes in an ATP-dependent manner11,12 (Fig. S1a,b). The BRG1/BRM ortholog SWSN-4 provides the complex’s catalytic activity and comprises, together with SWSN-1/BAF155/170 and SNFC-5/INI1, its core subunits13. Additional accessory subunits direct the specificity of the complex. In particular two subclasses of SWI/SNF, BAF and PBAF, which differ by the presence of accessory signature subunits (i.e. SWSN-8/OSA and PBRM-1/Polybromo (Fig. S1a,b)), show distinct functions14,15. Although chromatin remodelling is a ubiquitous process, the roles of SWI/SNF are surprisingly confined. For example, in yeast only 6% of all gene expression events depend on SWI/SNF16, suggesting that particular mechanisms direct SWI/SNF to specific sites.

In C. elegans, studies on SWI/SNF have remained few – mostly focused on its role in asymmetric T-cell division and gonad morphogenesis15,17. To explore the relationship between DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF, we first confirmed the interaction between DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF subunits (including its catalytic core SWSN-4/BRG1) and excluded the possibility of a DNA-mediated interaction by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) in the presence of Benzonase, a nuclease that degrades DNA and RNA (Fig. 1d,e). Next we determined in which tissues and subcellular compartments DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF are coexpressed and hence their interaction may occur. Both were expressed globally, including the tissues important for DAF-16/FOXO function (i.e. intestine and neurons)17,18 (Fig. S1c). While inactive DAF-16/FOXO (e.g. in daf-18(mg198lf)) is sequestered in the cytoplasm and only translocates to the nucleus upon its activation (e.g. in daf-2(e1370ts)), SWI/SNF subunits resided constitutively in the nucleus15,17,19 (Fig. S1c, data not shown). Consistent with this observation, mass spectrometric comparison of the DAF-16/FOXO purifications from wild-type, daf-2(e1370ts), and daf-18(mg198lf) animals revealed a positive correlation between the activation of DAF-16/FOXO and its binding to SWI/SNF (comparison based on spectral counts, Table S1). Thus it appears that DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF encounter each other in most cell types, with their interaction preferentially occurring upon DAF-16/FOXO activation and translocation into the nucleus, i.e. under low insulin-like signalling conditions.

SWI/SNF is required for DAF-16/FOXO-mediated transcriptional regulation

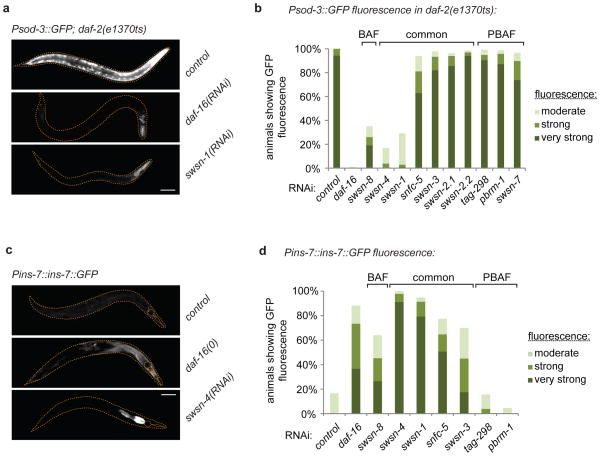

Next we evaluated the importance of SWI/SNF for DAF-16/FOXO activity. Since DAF-16/FOXO exerts its function by transcriptional regulation of target genes, we tested whether SWI/SNF is required for this regulation to occur. We used transcriptional reporters of two DAF-16/FOXO-regulated genes, sod-3 and ins-7, to examine DAF-16/FOXO-dependent transcriptional activation and repression, respectively6,20. Expression of the Psod-3::GFP reporter is induced under conditions of low insulin-like signalling, e.g. in daf-2 mutants18. Additional inactivation by RNAi of DAF-16/FOXO or of the SWI/SNF core subunits SWSN-4/BRG1, SWSN-1/BAF155/170 and the BAF-subclass signature subunit SWSN-8/OSA, suppressed this induction of Psod-3::GFP (Fig. 2a,b). Likewise, repression of Pins-7::ins-7::GFP was suppressed by RNAi against SWI/SNF subunits, in particular SWSN-4/BRG1 and SWSN-1/BAF155/170 and to a lesser extent SWSN-8/OSA, SWSN-3/BAF57, and SNFC-5/INI1 (Fig. 2c,d). It is important to note that in contrast to the BAF-subclass signature subunit SWSN-8/OSA, RNAi against the PBAF-subclass signature subunits PBRM-1/Polybromo, TAG-298/BRD7, or SWSN-7/BAF200 (by validated RNAi conditions (Fig. S2)) yielded no significant phenotypes in these assays, suggesting that specifically a BAF-like subclass of the SWI/SNF complex mediates DAF-16/FOXO functions.

Figure 2.

A BAF-like subclass of SWI/SNF is required for regulation of DAF-16/FOXO target genes. Psod-3::GFP; daf-2(e1370ts) or Pins-7::ins-7::GFP animals were grown from the L1-stage on indicated RNAi bacteria. daf-2(e1370ts) was inactivated by shift to restrictive temperature at the L4-stage. GFP-fluorescence was evaluated on day 4 of adulthood (n=50 animals). Representative images are shown (scale bar: 100 μm) (a,c). Common SWI/SNF subunits or ones specific to the subclasses BAF or PBAF are indicated accordingly (b,d).

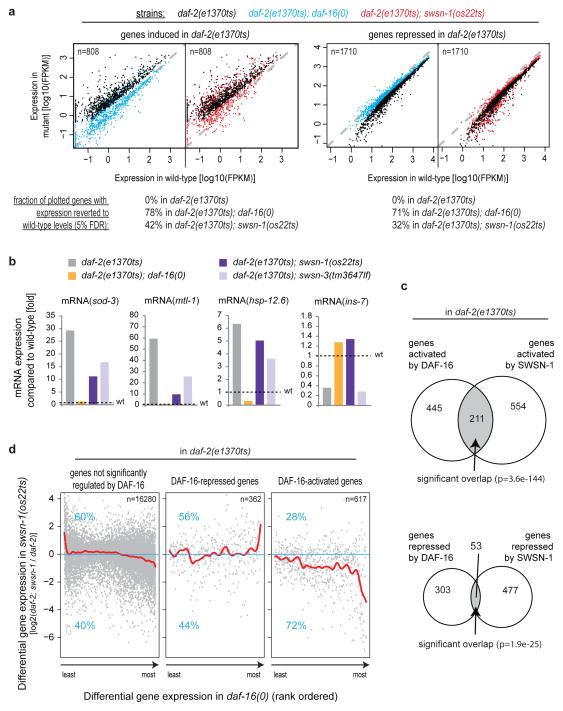

We then tested whether SWI/SNF is required for the regulation of endogenous DAF-16/FOXO target genes genome-wide. By high-throughput sequencing of mRNA (mRNA-Seq), we compared gene expression levels between wild-type, daf-2(e1370ts), daf-2(e1370ts); daf-16(0), and daf-2(e1370ts); swsn-1(os22ts) young adult animals at restrictive temperature. First we tested whether daf-16(0) or swsn-1(os22ts) could suppress the differential gene expression caused by decreased insulin-like signalling in daf-2(e1370ts), which is thought to be entirely mediated by DAF-16/FOXO3. As indicated by an extensive reversal of the differential gene expression to wild-type levels (78% of genes activated and 71% of genes repressed in the daf-2(e1370ts) mutant), daf-16(0) largely suppressed the gene expression changes induced by daf-2(e1370ts) (Fig. 3a,b). Likewise swsn-1(os22ts) significantly reversed this differential gene expression, although to a lesser extent (42% of genes activated and 32% of genes repressed in the daf-2(e1370ts) mutant were reverted; Fig. 3a,b). This could be due to swsn-1(os22ts) being a non-null and therefore weaker allele than daf-16(0), SWSN-1 being less important, or it acting on only a subset of DAF-16/FOXO target genes. Next we determined the overlap between DAF-16/FOXO- and SWI/SNF-regulated genes. Importantly, although DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF each regulate only a small fraction of the genome (5.9% and 7.5%, respectively), their dependent gene sets showed substantial and significant overlap: Of the 656 genes activated and 356 genes repressed by DAF-16/FOXO in daf-2(e1370ts) animals, 32% (211) of the activated and 15% (53) of the repressed genes were co-regulated by SWI/SNF (Fig. 3c), suggesting that a large fraction of DAF-16/FOXO-mediated gene regulatory events require SWI/SNF. GO-term analysis of the co-dependent genes showed significant enrichment for genes involved in aging, oxidative stress response, and organismal defence (Table S7). Focusing on DAF-16/FOXO target genes, specifically for genes activated by DAF-16/FOXO we observed a strong positive correlation between the extent of DAF-16/FOXO-mediated activation and the requirement of SWI/SNF for this activation to occur (as indicated by a declining trendline in Figure 3d, right panel). No such substantial correlation was found for genes non-regulated or repressed by DAF-16/FOXO (Fig. 3d, left and middle panels). Thus SWI/SNF is required for the regulation of a large subset of DAF-16/FOXO target genes – predominantly those activated by DAF-16/FOXO.

Figure 3.

SWI/SNF is required for regulation of a large fraction of DAF-16/FOXO target genes – in particular those activated by DAF-16/FOXO. Wild-type, daf-2(e1370ts), daf-2(e1370ts); daf-16(0), and daf-2(e1370ts); swsn-1(os22ts) C. elegans were grown to the L4-stage, then shifted to restrictive temperature. After 20 h, genome-wide mRNA expression levels were determined by mRNA-Seq. (a) Scatter-plots comparing gene expression in wild-type to that of various mutant strains. Only genes either significantly induced by daf-2(e1370ts) (left panel) or repressed by daf-2(e1370ts) (right panel) are shown. Colours indicate the strains in which the gene expression was analysed. As indicated by reversion of many genes to wild-type expression levels (shift of genes to the plots’ indicated diagonals), daf-16(0) extensively and swsn-1(os22ts) partially suppress the gene expression changes of daf-2(e1370ts) animals. (b) Confirmation of the mRNA-Seq data by quantitative RT-PCR, looking at the expression levels of endogenous sod-3, mtl-1, hsp-12.6, and ins-7. Expression levels shown are relative to wild-type levels (black dotted lines). Consistent with the mRNA-Seq results, daf-16(0) tends to fully and mutants in SWI/SNF tend to partially suppress the differential gene expression caused by daf-2(e1370ts). (c) Significant overlap between genes regulated by DAF-16/FOXO and SWSN-1/BAF155/170 (hypergeometric test). Genes downregulated in either daf-2(e1370ts); daf-16(0) or daf-2(e1370ts); swsn-1(os22ts) compared to daf-2(e1370ts) are shown in the upper diagram, genes upregulated in these comparisons are shown in the lower diagram. (d) Correlation between the extent of DAF-16/FOXO- and SWI/SNF-mediated differential gene expression in daf-2(e1370ts) animals. Red lines represent trendlines, blue numbers show the fraction of genes that are either up- or downregulated in swsn-1(os22ts), n denotes the number of DAF-16/FOXO-non-regulated, repressed, or activated genes contributing to each of the plots. Specifically for genes activated by DAF-16/FOXO in daf-2(e1370ts), the extent of DAF-16/FOXO-mediated activation correlates with an increasing dependence on SWI/SNF, as indicated by the declining trendline in the plot on the right.

DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF colocalize on chromatin

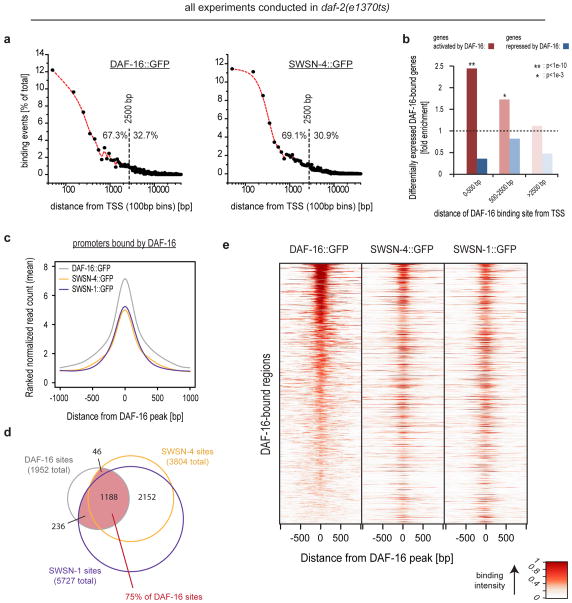

We then sought the mechanism by which SWI/SNF impacts DAF-16/FOXO-mediated gene regulation. Given that SWI/SNF and activated DAF-16/FOXO are both known to associate with DNA2,11,12, we determined the genome-wide positioning of DAF-16/FOXO, the SWI/SNF catalytic subunit SWSN-4/BRG1, and the SWI/SNF core regulatory subunit SWSN-1/BAF155/170 in daf-2(e1370ts) animals at restrictive temperature using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-Seq). Using strains expressing either DAF-16::GFP, SWSN-4::GFP, or SWSN-1::GFP, we identified 1952 binding sites for DAF-16/FOXO, 3804 binding sites for SWSN-4/BRG1, and 5727 binding sites for SWSN-1/BAF155/170. Despite our use of multi-copy transgenes that may express at non-physiological levels, we observed a reassuring enrichment for the canonical DAF-16/FOXO associated motif TRTTTAC3 at DAF-16/FOXO binding sites. SWSN-4/BRG1 and SWSN-1/BAF155/170 binding sites were likewise enriched for several motifs, although motifs of less defined roles (Table S8). Interestingly, not only SWI/SNF but also DAF-16/FOXO binding sites shared enrichment for a motif known to associate with Trithorax-like, a protein of Drosophila melanogaster that is functionally related to SWI/SNF21 (Table S8). DAF-16/FOXO binding sites in daf-2(e1370ts) correlated well with DAF-16/FOXO binding sites previously identified in wild-type animals4 (Fig. S3a). And DAF-16/FOXO as well as SWI/SNF binding sites were mostly located within promoter regions, consistent with these proteins functioning in transcriptional regulation (Fig. 4a). Genes immediately downstream of DAF-16/FOXO binding sites were strongly enriched for DAF-16/FOXO-activated genes, while they were depleted for DAF-16/FOXO-repressed genes (Fig. 4b). 87% of the directly regulated genes experienced activation and only 13% repression by DAF-16/FOXO, suggesting that DAF-16/FOXO is predominantly a transcriptional activator.

Figure 4.

SWI/SNF extensively associates with DAF-16/FOXO-bound promoter regions. C. elegans of either daf-2(e1370ts); DAF-16::GFP, daf-2(e1370ts); SWSN-4::GFP, or daf-2(e1370ts); SWSN-1::GFP were grown asynchronously and e1370ts was inactivated by a 20h shift to restrictive temperature. ChIP-Seq of GFP-tagged proteins was performed and binding sites were determined. (a) Each binding site was associated with its closest transcriptional start site (TSS) and distances were plotted, revealing that DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF are predominantly located within 2.5 kb of a TSS and thus within promoter regions. (b) Genes in vicinity to a DAF-16/FOXO binding site are strongly enriched for DAF-16/FOXO-activated and rather depleted for DAF-16/FOXO-repressed genes. This effect decays with the distance of the binding site from the TSS. (c) DAF-16/FOXO bound promoter regions are strongly enriched for binding by SWSN-4::GFP and SWSN-1::GFP. Mean read distributions across all DAF-16/FOXO binding sites are shown for the indicated strains. (d) Venn diagram showing the overlap between binding sites of DAF-16/FOXO, SWSN-4/BRG1, and SWSN-1/BAF155/170. (e) Heat-map representation of the data contributing to (c,d), further supporting that SWI/SNF binding occurs at the majority of DAF-16/FOXO binding sites. Lines of the heat-map represent the individual DAF-16/FOXO-bound regions and are sorted by intensity of DAF-16/FOXO binding.

Given that DAF-16/FOXO and SWI/SNF form a complex (Fig. 1d,e, Table S1), we tested if they would colocalize also on chromatin. Indeed, SWSN-4/BRG1 and SWSN-1/BAF155/170 were strongly enriched right at the summits of DAF-16/FOXO binding sites (Fig. 4c,e), supporting the model of DAF-16/FOXO-SWI/SNF interaction. And the fact that this colocalization occurred not only at some but the majority DAF-16/FOXO binding sites (Fig. 4d,e), further supports the intimate connection between DAF-16/FOXO and this cofactor.

DAF-16/FOXO recruits SWI/SNF to directly activated target genes

There is substantial precedence for transcription factors to employ chromatin remodellers as cofactors12. In the case of SWI/SNF, some transcription factors recruit it to target promoters to induce local nucleosome repositioning which alters the accessibility of cis-regulatory promoter elements to regulate transcription22. In order to test if DAF-16/FOXO employs SWI/SNF in a similar manner, we investigated whether their binding to DAF-16/FOXO target promoters depends on each other. Inactivation of SWI/SNF by use of swsn-1(os22ts) at restrictive temperature had no effect on DAF-16/FOXO expression, nuclear localization, nor its binding to target promoters (Fig. 5a, S3b,c). Next we looked at the SWI/SNF catalytic core subunit, SWSN-4/BRG1. Again, loss of DAF-16/FOXO did not alter SWSN-4/BRG1 expression levels (Fig. S3b), its nuclear localization (Fig. S3c), nor did we observe significant changes in the abundance of SWSN-4/BRG1 at promoters that were either non-regulated or repressed by DAF-16/FOXO (Fig. 5b). However, specifically at a large fraction of promoters that were directly bound and activated by DAF-16/FOXO (e.g. promoters of sod-3, ctl-3, or hil-1) we observed a substantial loss of SWSN-4/BRG1 binding in the absence of DAF-16/FOXO (Fig. 5b,d, S4a). As an additional control, we investigated promoters that were activated by DAF-16/FOXO (as judged by mRNA-Seq) but were lacking a DAF-16/FOXO binding site, assuming that these are only indirect targets of DAF-16/FOXO, e.g. regulated by transcription factors or other events downstream of DAF-16/FOXO. Here we observed no change in SWSN-4/BRG1 binding upon loss of DAF-16/FOXO, suggesting that SWSN-4/BRG1 recruitment at directly DAF-16/FOXO-activated promoters is indeed controlled by the physical presence of DAF-16/FOXO and not mere events of transcriptional activation (Fig. 5b). Findings for SWSN-4/BRG1 were confirmed by analysis of SWSN-1/BAF155/170, yielding similar results (Fig. 5c, S3b, S4a, data not shown). Results were additionally confirmed and replicated by conventional ChIP-qPCR experiments (Fig. S4b). We conclude that DAF-16/FOXO can employ SWI/SNF as a cofactor in the manner previously described for other transcription factors, and hence we infer the following model for how DAF-16/FOXO may activate its target genes: DAF-16/FOXO binds promoters independent of SWI/SNF, presumably by directly accessing its target sequences, and at promoters that DAF-16/FOXO directly activates, it aids the recruitment of SWI/SNF, thereby inducing local chromatin remodelling. This remodelling enhances accessibility of activatory cis-regulatory promoter elements for binding by downstream components (e.g. the transcription machinery), thereby resulting in transcriptional activation (Fig. S5).

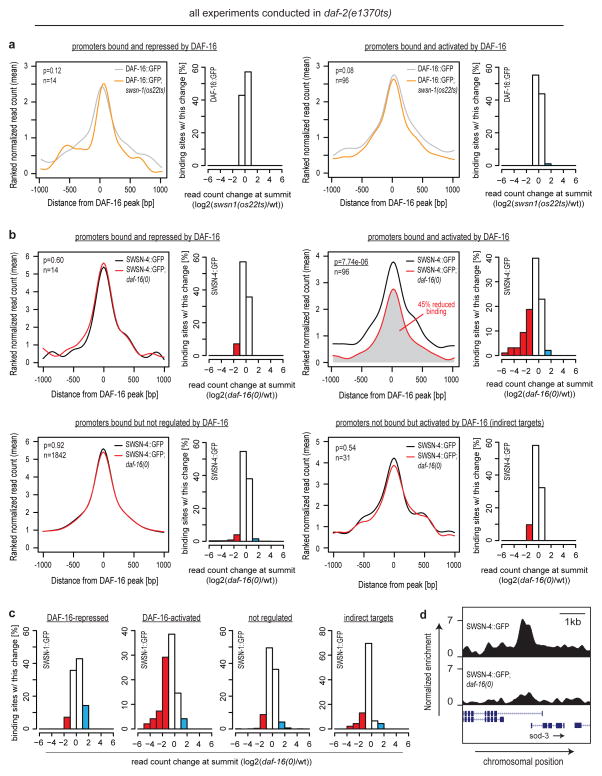

Figure 5.

DAF-16/FOXO recruits SWI/SNF specifically to target promoters that are directly activated by DAF-16/FOXO. C. elegans of either daf-2(e1370ts); DAF-16::GFP, daf-2(e1370ts); swsn-1(os22ts); DAF-16::GFP, daf-2(e1370ts); SWSN-4::GFP, daf-2(e1370ts); daf-16(0); SWSN-4::GFP, daf-2(e1370ts); SWSN-1::GFP, or daf-2(e1370ts); daf-16(0); SWSN-1::GFP were grown asynchronously and e1370ts and os22ts alleles were inactivated by a 20h shift to restrictive temperature. ChIP-Seq of GFP-tagged proteins was performed. (a) DAF-16/FOXO binding to promoter regions is not affected by absence of SWI/SNF. Mean read distributions across different subsets of DAF-16/FOXO target promoters are shown for the indicated strains. n denotes the number of promoter regions used in each analysis and p-values denote the significance of the change in DAF-16/FOXO binding. Corresponding histograms illustrate that hardly any of the promoters underwent a binding change larger than 2-fold. (b) Loss of DAF-16/FOXO impairs binding of SWSN-4/BRG1 specifically to promoters directly bound and activated by DAF-16/FOXO. Mean read distributions across different subsets of DAF-16/FOXO target promoters are shown for the indicated strains. n denotes the number of promoter regions used in each analysis and p-values denote the significance of the change in SWSN-4/BRG1 binding. Corresponding histograms illustrate the fraction of promoters that underwent a larger than 2-fold change in SWSN-4 binding (colored regions). (c) Histograms illustrating that loss of DAF-16/FOXO likewise impairs binding of SWSN-1/BAF155/170 specifically to promoters directly bound and activated by DAF-16/FOXO. (d) Prominent example of daf-16(0)-dependent changes in SWSN-4/BRG1 binding to the sod-3 promoter (a promoter directly bound and activated by DAF-16/FOXO). ChIP-Seq data was normalized, smoothed over 50 bp bins, and then displayed in the UCSC genome browser.

SWI/SNF is required for DAF-16/FOXO-mediated dauer formation

Given our collective evidence that DAF-16/FOXO employs SWI/SNF as a gene-activation-specific cofactor, we then wondered about the importance of this cofactor for the various DAF-16/FOXO-mediated functions in the animal. In C. elegans, DAF-16/FOXO is required for entry into the dauer state, a developmental arrest or diapause state that allows for survival in many adverse conditions23. We induced this state by inactivating insulin-like signalling and tested whether RNAi against SWI/SNF subunits was able to suppress it. Consistent with SWI/SNF being an important cofactor to DAF-16/FOXO, not only loss of daf-16 but also of several SWI/SNF subunits prevented the formation of SDS-resistant dauer larvae (Fig. 6a). Upon closer investigation, we found that in absence of SWI/SNF animals attempted dauer entry, but full execution of the dauer program failed, leading instead to a DAF-16/FOXO-dependent developmental arrest around the L3 stage (Fig. S6a). These arrested animals lacked the typical longevity of dauer larvae and frequently were void of dauer-specific anatomical features such as the hypodermal alae or the pharyngeal plug (Fig. S6b–d). Consistent with our gene expression data (Fig. 2b,d), defective dauer formation was specifically observed upon loss of either the core SWI/SNF subunits SWSN-4/BRG1 and SWSN-1/BAF155/170 or the BAF signature subunit SWSN-8/OSA, while loss of PBAF signature subunits PBRM-1/Polybromo, TAG-298/BRD7, or SWSN-7/BAF200 did not disrupt dauer formation. This once again implies a specific role for a BAF-like subclass of SWI/SNF in mediating DAF-16/FOXO functions.

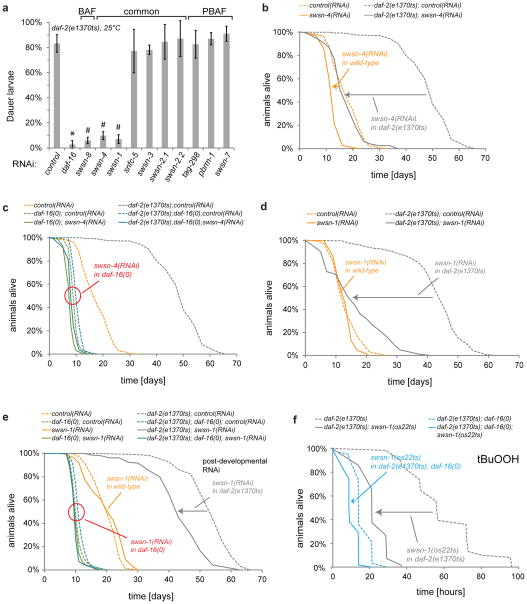

Figure 6.

SWI/SNF is required for DAF-16/FOXO-mediated dauer formation, stress resistance, and longevity. (a) Dauer suppression assay. Eggs of C. elegans with activated DAF-16/FOXO (daf-2(e1370ts)) were placed on the indicated RNAi bacteria and grown at restrictive temperature. Dauers were identified after 5 days based on morphology and their resistance to 1 % SDS. Common SWI/SNF subunits or ones specific to the subclasses BAF or PBAF are indicated accordingly. Marked RNAi clones (*,#) were significantly different from control RNAi (t-Test; p<0.05), some of which (#) led to non-dauer arrest around the L3 stage. (see Fig. S6a) (n=50 animals; error bars are based on S.D. from 3 independent experiments) (b–d) Lifespan phenotypes caused by inactivation of SWI/SNF. Indicated strains were grown from the L1-stage on indicated RNAi bacteria. Animals were shifted to restrictive temperature at the L4-stage. (e) Also post-developmental inactivation of SWI/SNF impairs DAF-16/FOXO-mediated longevity. Indicated C. elegans strains were grown from the L1-stage on E. coli HT115. At the L4-stage, animals were shifted to the indicated RNAi bacteria and e1370ts was inactivated by shift to restrictive temperature. (f) Oxidative stress resistance assay. Indicated strains were grown to the L4-stage, when e1370ts and os22ts alleles were inactivated by shift to restrictive temperature. 24 h later, animals were exposed to 6 mM tert-Butylhydroperoxide (tBuOOH) and their survival was monitored. All survival data of panels (b–f) was obtained from a minimum of 100 animals per condition, mean survival times and S.E.M. were obtained by Kaplan-Meier analysis, and significant differences between conditions were determined by log-rank test (for exact numbers of animals and statistical data see Table S9).

Given this loss-of-function phenotype for SWI/SNF, we also tested whether overexpression of the SWI/SNF subunits SWSN-4/BRG1 or SWSN-1/BAF155/170 could promote dauer formation. Although gain-of-function phenotypes from such approach may be difficult to obtain or interpret due to the multi-subunit nature of the SWI/SNF complex and its requirement to be targeted to the appropriate sites, we observed a daf-16-dependent moderate enhancement of dauer formation in daf-2(e1370ts) animals at 22°C (Fig. S6e).

SWI/SNF is required for DAF-16/FOXO-mediated longevity and stress resistance

Beyond its role in dauer formation, DAF-16/FOXO is a potent mediator of lifespan extension, in particular during decreased insulin-like signalling. Inactivation of the SWI/SNF core subunits SWSN-4/BRG1 or SWSN-1/BAF155/170 by RNAi fully suppressed this lifespan extension (Fig. 6b,d). Partial suppression was seen upon RNAi against the non-core subunit SWSN-3/BAF57 (Fig. S7a). Even post-developmental RNAi against SWI/SNF subunits was sufficient to partially suppress DAF-16/FOXO-induced lifespan extension (Fig. 6e, Fig. S7b). All lifespan phenotypes induced by SWI/SNF RNAi were diminished in daf-16(0) mutant worms, consistent with SWI/SNF functioning as a cofactor to and thus in the same pathway as DAF-16/FOXO (Fig. 6c,e, Fig. S7b). We further confirmed these phenotypes by mutant analysis. Consistent with the RNAi results, the hypomorphic alleles swsn-4(os13ts) and swsn-1(os22ts) each impaired DAF-16/FOXO-mediated lifespan extension (Fig. S7c,d). Unlike other SWI/SNF alleles or RNAi conditions tested, the particularly strong allele swsn-1(os22ts) shortened the lifespan of daf-16(0) animals, showing that SWI/SNF has some lifespan effects that are independent of DAF-16/FOXO. But consistent with a requirement of SWI/SNF for DAF-16/FOXO function and thus the two acting in the same pathway, daf-16(0) failed to shorten the lifespan of swsn-1(os22ts) animals (Fig. S7d).

The lifespan extending capabilities of DAF-16/FOXO are highly correlated with its ability to induce stress response pathways3,24. We tested if SWI/SNF is required for the DAF-16/FOXO-mediated stress resistance of insulin-like signalling mutants. Inactivation of SWI/SNF by swsn-1(os22ts) or swsn-3(RNAi) specifically blocked the enhanced resistance of daf-2 mutants to oxidative stress (tBuOOH, Fig. 6f, S7e). In addition, swsn-1(os22ts) was able to block enhanced resistance of daf-2 mutants to heat stress (32°C, Fig. S7f). Inactivation of SWI/SNF showed a much lesser effect in daf-16 mutant backgrounds (Fig. 6f, S7e,f), again suggesting that SWI/SNF functions in the same pathway as DAF-16/FOXO. Thus consistent with SWI/SNF being an important cofactor to DAF-16/FOXO, it is not only required for DAF-16/FOXO-mediated gene regulation, but it actually is required for a broad range of DAF-16/FOXO-mediated functions in the animal, in particular dauer formation, stress resistance, and the promotion of longevity.

Discussion

Despite our extensive knowledge of pathways leading to DAF-16/FOXO activation, it long remained elusive by which means and the help of which cofactors activated DAF-16/FOXO regulates transcription and thus confers its suite of beneficial effects upon the organism. Our study provided the first systematic identification of DAF-16/FOXO cofactors, which in itself provides a significant resource for future studies, and by focusing on its most prominent candidate, the chromatin remodeller SWI/SNF, we were able to illuminate the transcription-regulatory events downstream of DAF-16/FOXO activation. We showed that DAF-16/FOXO is predominantly a transcriptional activator and provided mechanistic insight into how this activation may be achieved – namely by DAF-16/FOXO recruiting a BAF-like subclass of SWI/SNF to target promoters. Extensive exploration of SWI/SNF function in other systems suggests that this recruitment induces local chromatin remodelling to enable binding of downstream transcriptional components and thereby activates transcription22. These findings also jibe with previous implications of DAF-16/FOXO as a pioneer transcription factor25,26, suggesting that specifically upon pro-longevity stimuli DAF-16/FOXO is activated and autonomously binds to a wide range of target promoters where it nucleates their transcriptional activation by alteration of chromatin states.

Chromatin states and their alteration were previously shown to have profound stress responsive and lifespan-regulatory effects, but those described alterations were mostly limited to epigenetic changes (i.e. histone methylation27,28 or acetylation29) and their mechanistic link to known stress responsive and lifespan-regulatory pathways often remained unclear. We now established DAF-16/FOXO-controlled stress-responsive and lifespan-regulatory roles for a type of chromatin alteration fundamentally distinct from epigenetic changes, namely ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling at the hands of SWI/SNF. This opens a new dimension to how an alteration of chromatin states can regulate stress response and longevity. Also any potential cross-talk between this ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling and lifespan-regulatory epigenetic marks will be important to investigate in the future. For example, enrichment of SWI/SNF at DAF-16/FOXO binding sites is substantially but not entirely dependent on DAF-16/FOXO (Fig. 5b–d, Fig. S4) and thus may be supported by other factors or epigenetic marks, with histone acetylation being a strong candidate30.

Finally, we would like to note that FOXO and SWI/SNF are both evolutionarily conserved and that FOXO also has lifespan regulatory roles in humans31,32. Hence the here described roles of SWI/SNF may be conserved, and their further exploration may eventually benefit our understanding of aging and age-related diseases in humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hitoshi Sawa, Shohei Mitani, Marlene Hansen, and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for strains. We thank Gabriel Hayes, Ulandt Kim, Mark Borowski, Ania Puczinska, and Daniel Grau for experimental support. We thank Iain Cheeseman, Karim Bouazoune, Matthew Simon, Behfar Ardehali, William Mair, Taiowa Montgomery, and the Avruch lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to G.R. (AG014161 and AG016636), J.M.A. (5P30CA006516 and 2P01CA120964), J.A.W. (F32GM093491), N.V.K. (F32AI100501-01), and R.E.K. (GM048405). C.G.R. was supported by long-term fellowships from the Human Frontier Science Program and the European Molecular Biology Organization, R.H.D. by the American Cancer Society (122240-PF-12-078-01-RMC), N.V.K. by a Tosteson Postdoctoral Fellowship Award, S.K.B. by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, and T.H. by the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

C.G.R. and G.R. conceived and designed the experiments. C.G.R., G.F.L., N.V.K., J.A.W., and J.M.A. conducted the experiments. R.H.D. analysed the mRNA-Seq and ChIP-seq data. S.K.B., R.E.K., T.H., and A.D. provided unpublished methods, materials, and advice. C.G.R. and G.R. wrote the manuscript.

Competing Financial Interests:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kenyon C. The plasticity of aging: insights from long-lived mutants. Cell. 2005;120:449–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calnan DR, Brunet A. The FoxO code. Oncogene. 2008;27:2276–88. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy CT, et al. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:277–83. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerstein MB, et al. Integrative analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome by the modENCODE project. Science. 2010;330:1775–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1196914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berdichevsky A, Viswanathan M, Horvitz HR, Guarente L. C elegans SIR-2.1 interacts with 14-3-3 proteins to activate DAF-16 and extend life span. Cell. 2006;125:1165–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuelson AV, Carr CE, Ruvkun G. Gene activities that mediate increased life span of C elegans insulin-like signaling mutants. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2976–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.1588907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pollina EA, Brunet A. Epigenetic regulation of aging stem cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:3105–26. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–32. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Margalit A, et al. Barrier to autointegration factor blocks premature cell fusion and maintains adult muscle integrity in C. elegans. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:661–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curran SP, Ruvkun G. Lifespan regulation by evolutionarily conserved genes essential for viability. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e56. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon CS, Wagner D. Unwinding chromatin for development and growth: a few genes at a time. Trends Genet. 2007;23:403–12. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hargreaves DC, Crabtree GR. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics and mechanisms. Cell Res. 2011;21:396–420. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phelan ML, Sif S, Narlikar GJ, Kingston RE. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol Cell. 1999;3:247–53. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moshkin YM, Mohrmann L, Van Ijcken WFJ, Verrijzer CP. Functional differentiation of SWI/SNF remodelers in transcription and cell cycle control. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:651–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01257-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shibata Y, Uchida M, Takeshita H, Nishiwaki K, Sawa H. Multiple functions of PBRM-1/Polybromo- and LET-526/Osa-containing chromatin remodeling complexes in C. elegans development. Dev Biol. 2012;361:349–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holstege FC, et al. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell. 1998;95:717–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81641-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawa H, Kouike H, Okano H. Components of the SWI/SNF complex are required for asymmetric cell division in C. elegans. Mol Cell. 2000;6:617–24. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115:489–502. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson ST, Johnson TE. daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1975–80. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy CT, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Tissue entrainment by feedback regulation of insulin gene expression in the endoderm of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:19046–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709613104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farkas G, et al. The Trithorax-like gene encodes the Drosophila GAGA factor. Nature. 1994;371:806–8. doi: 10.1038/371806a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson CL, Workman JL. Promoter targeting and chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10:187–92. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fielenbach N, Antebi A. C elegans dauer formation and the molecular basis of plasticity. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2149–2165. doi: 10.1101/gad.1701508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SS, Kennedy S, Tolonen AC, Ruvkun G. DAF-16 target genes that control C. elegans life-span and metabolism. Science. 2003;300:644–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1083614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaret KS, Carroll JS. Pioneer transcription factors: establishing competence for gene expression. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2227–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.176826.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatta M, Cirillo LA. Chromatin opening and stable perturbation of core histone:DNA contacts by FoxO1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35583–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704735200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greer EL, et al. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2011;479:365–71. doi: 10.1038/nature10572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greer EL, et al. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;466:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature09195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Longo VD, Kennedy BK. Sirtuins in aging and age-related disease. Cell. 2006;126:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterjee N, et al. Histone H3 tail acetylation modulates ATP-dependent remodeling through multiple mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:8378–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flachsbart F, et al. Association of FOXO3A variation with human longevity confirmed in German centenarians. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106:2700–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809594106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willcox BJ, et al. FOXO3A genotype is strongly associated with human longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:13987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801030105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.