Abstract

Background:

In the last decade, the number of total knee replacements performed annually in the United States has doubled, with disproportionate increases among younger adults. While total knee replacement is a highly effective treatment for end-stage knee osteoarthritis, total knee replacement recipients can experience persistent pain and severe complications. We are aware of no current estimates of the prevalence of total knee replacement among adults in the U.S.

Methods:

We used the Osteoarthritis Policy Model, a validated computer simulation model of knee osteoarthritis, and data on annual total knee replacement utilization to estimate the prevalence of primary and revision total knee replacement among adults fifty years of age or older in the U.S. We combined these prevalence estimates with U.S. Census data to estimate the number of adults in the U.S. currently living with total knee replacement. The annual incidence of total knee replacement was derived from two longitudinal knee osteoarthritis cohorts and ranged from 1.6% to 11.9% in males and from 2.0% to 10.9% in females.

Results:

We estimated that 4.0 million (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.6 million to 4.4 million) adults in the U.S. currently live with a total knee replacement, representing 4.2% (95% CI: 3.7% to 4.6%) of the population fifty years of age or older. The prevalence was higher among females (4.8%) than among males (3.4%) and increased with age. The lifetime risk of primary total knee replacement from the age of twenty-five years was 7.0% (95% CI: 6.1% to 7.8%) for males and 9.5% (95% CI: 8.5% to 10.5%) for females. Over half of adults in the U.S. diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis will undergo a total knee replacement.

Conclusions:

Among older adults in the U.S., total knee replacement is considerably more prevalent than rheumatoid arthritis and nearly as prevalent as congestive heart failure. Nearly 1.5 million of those with a primary total knee replacement are fifty to sixty-nine years old, indicating that a large population is at risk for costly revision surgery as well as possible long-term complications of total knee replacement.

Clinical Relevance:

These prevalence estimates will be useful in planning health services specific to the population living with total knee replacement.

Total knee replacement is widely used to relieve pain and improve functional status in patients with symptomatic, end-stage knee osteoarthritis1-3. In the last decade, the number of primary total knee replacements performed annually in the U.S. doubled, exceeding 620,000 procedures in 2009, with >97% of these performed for a principal diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis4,5.

Total knee replacement is an effective treatment for end-stage knee osteoarthritis, with symptomatic improvement exceeding 85% and long-term failure rates of <1% per year6-8. However, individuals who undergo total knee replacement are at risk for a variety of complications, such as infection, periprosthetic fracture, symptomatic implant loosening, and implant wear leading to mechanical failure9,10. These complications substantially diminish the benefits of total knee replacement and often necessitate revision surgery11.

Growth in total knee replacement utilization has been disproportionately high among younger individuals (forty-five to sixty-four years old)12-14. As a result, the average age at which patients receive total knee replacement has decreased over time4. The rapid growth in total knee replacement utilization among younger adults, coupled with increased life expectancy, implies that many more individuals are living with total knee replacement longer than ever before.

Despite a high success rate and relatively low risks of failure and/or complications, as more adults in the U.S. undergo total knee replacement, the population at risk for such complications increases. While the annual utilization of total knee replacement over time has been described12,14,15, estimates of the number of persons in the U.S. living with knee implants have not been reported, to our knowledge. Such estimates would be useful in planning health services specific to the population living with total knee replacement, such as anticipation of revision total knee replacement and management of periprosthetic fractures and infections. We aimed to quantify the burden of total knee replacement in the U.S. by estimating the number of adults currently alive with a primary or revision total knee replacement.

Materials and Methods

Analytic Overview

We used the Osteoarthritis Policy (OAPol) Model, a validated computer simulation model of the natural history and management of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, combined with data on total knee replacement incidence, to estimate the prevalence of primary and revision total knee replacement among adults in the U.S. and to derive the lifetime risk of primary and revision total knee replacement in the U.S. The annual incidence of total knee replacement among persons with advanced knee osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence grade 3 or 4) was derived from two multicenter longitudinal studies of persons with knee osteoarthritis (the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study [MOST] and the Osteoarthritis Initiative [OAI])16,17. We combined estimates of the prevalence of total knee replacement with 2009 U.S. Census data to calculate the number of adults in the U.S. currently living with total knee replacement.

OAPol Model

The OAPol Model is a validated, state transition, computer simulation model of the natural history of knee osteoarthritis18,19. “State transition” implies that the natural history and outcomes of clinical management of knee osteoarthritis are characterized as a series of annual transitions between health states. The model is implemented as a Monte Carlo simulation, meaning that the health-state-to-health-state pathway followed by an individual hypothetical subject is determined by a random-number generator and a set of estimated transition probabilities between states. This simulation is repeated for at least one million individuals to achieve stable estimates.

Health states in the model are defined by knee osteoarthritis severity and the presence or absence of several comorbidities (obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and musculoskeletal disorders not including osteoarthritis). Death can occur from any health state, although the presence of certain comorbidities (obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and cancer) increases an individual’s risk of mortality. Further details of health states in the OAPol Model are published elsewhere19.

Model Input Parameters

Baseline Cohort Demographics

We simulated male and female cohorts from the age of twenty-five years until death. We used data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for 2005 through 2008 for individuals from twenty to twenty-nine years old to estimate the distribution of baseline body mass index (BMI), stratified by sex (Table I)20,21. The OAPol Model simulates changes in BMI with age, according to a model derived from NHANES data that has been previously described19.

TABLE I.

Model Input Parameters

| Parameter | Estimate | Source of Data* |

| Mean BMI (and stand. dev.) at age of 25 yr† (kg/m2) | NHANES 2005-200820,21 | |

| Male | 27.0 ± 6.1 | |

| Female | 27.6 ±7.8 | |

| Annual incidence of total knee replacement, given end-stage knee osteoarthritis (95% CI) (%) | Wise et al.23 and OAI16 | |

| <45 yr old | ||

| Male | 1.6 (0.8, 2.4) | |

| Female | 2.0 (1.1, 2.9) | |

| 45-64 yr old | ||

| Male | 6.4 (3.0, 9.7) | |

| Female | 8.1 (4.5, 11.8) | |

| 65-84 yr old | ||

| Male | 11.9 (6.7, 17.0) | |

| Female | 10.9 (6.5, 15.3) | |

| ≥85 yr old | ||

| Male | 3.0 (1.7, 4.3) | |

| Female | 2.7 (1.6, 3.8) | |

| Annual failure of total knee replacement leading to revision (%) | Paxton et al.6 | |

| <65 yr old | ||

| First year | 1.9 | |

| Subsequent years | 1.5 | |

| ≥65 yr old‡ | ||

| First year | 1.0 | |

| Subsequent years | 0.4 |

NHANES = National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, and OAI = Osteoarthritis Initiative.

BMI = body mass index.

For individuals who were eighty-five years of age or older, only 10% of primary total knee replacement failures were revised on the basis of data that show few revision total knee replacements are performed in patients over this age.

Incidence and Progression of Knee Osteoarthritis

The annual incidence of physician-diagnosed, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, stratified by age, sex, and obesity, was derived using data from the National Health Interview Survey. These data have been previously presented22. In our model, all incident cases of knee osteoarthritis were considered to be Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2 accompanied by knee pain. Progression from Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2 to grade 3 and, subsequently, Kellgren-Lawrence grade 4 was based on previously published rates of the annual progression of knee osteoarthritis19.

Nonsurgical Treatment for Knee Osteoarthritis

All individuals who developed symptomatic knee osteoarthritis underwent a sequence of treatment regimens, which were modeled on the basis of the most recent evidence-based clinical practice guidelines1-3. Nonsurgical treatments, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, and intra-articular corticosteroid injections, could provide pain relief, but did not affect structural disease progression. No individual with knee osteoarthritis was deemed eligible for total knee replacement until first failing early treatments; however, we assumed a limited efficacy of these treatments for individuals with advanced knee osteoarthritis.

Incidence of Primary Total Knee Replacement

We estimated the annual incidence of total knee replacement for individuals with end-stage knee osteoarthritis, using two multicenter, longitudinal, observational studies of individuals with knee osteoarthritis: MOST and OAI16,17. We used published data from MOST to derive the overall annual incidence of total knee replacement among individuals with Kellgren-Lawrence grade-3 or 4 knee osteoarthritis23. We utilized secondary data from the progression subcohort of the OAI to estimate the total knee replacement incidence per person-years at risk (with at risk defined as having frequent knee symptoms and Kellgren-Lawrence grade-3 or 4 osteoarthritis), stratified by sex and age (less than sixty-five years versus sixty-five years or older). We used the distribution of age and sex and the relative risk of total knee replacement for each age and sex combination in the OAI data to stratify our MOST-based incidence estimates by age and sex, using published methodology24. Since persons younger than forty-five years and older than eighty-five years of age were not included in the MOST or OAI studies, we conservatively estimated total knee replacement rates in these age groups by reducing annual incidence by 75%, on the basis of national data that show considerably fewer total knee replacements are performed before the age of forty-five years and after the age of eighty-five years4. We examined the effect of this assumption by performing a sensitivity analysis, in which we did not reduce the incidence of total knee replacement in these age groups. The resulting incidence rates of total knee replacement among individuals with end-stage knee osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence grade 3 or 4) are shown in Table I.

To account for variability in both data sources (MOST and OAI), we derived 95% confidence intervals (CI) around each age-specific and sex-specific estimate of the incidence of total knee replacement (Table I)24. We conducted our analysis in a probabilistic fashion, drawing 500 random sets of incidence rates of total knee replacement from the distributions presented in Table I. From this analysis, we calculated the mean and 95% CI around our estimates of the prevalence of total knee replacement. Additionally, because the OAPol Model does not account for secular changes in total knee replacement utilization over the past few decades, we performed sensitivity analyses, in which we increased and decreased all total knee replacement incidence values by 25% to determine the impact this might have on current prevalence estimates.

Total Knee Replacement Failure and Revision

Rates of total knee replacement failure leading to revision were derived from published data from Kaiser Permanente’s large U.S. joint replacement registry6. We dichotomized total knee replacement failure rate by first-year compared with subsequent-year failures (Table I). This assumption was based on data suggesting that failure rate and long-term polyethylene wear are linear after the first year25,26. We assumed individuals younger than eighty-five years of age who had a total knee replacement failure accepted revision surgery. We assumed limited (10%) acceptance of revision surgery among individuals who were eighty-five years of age or older, on the basis of data suggesting that few revisions are performed in this age group4.

Estimating the Prevalence of Total Knee Replacement

We estimated the prevalence of total knee replacement among adults in the U.S. fifty years of age or older. Using data from the OAPol Model-based simulations, we calculated the proportion of males and females with primary and revision total knee replacement among those alive at each year from the age of fifty to ninety-nine years. We weighted these age and sex-specific prevalence estimates by corresponding U.S. population estimates to determine the prevalence within ten-year age strata (fifty to fifty-nine years, sixty to sixty-nine years, seventy to seventy-nine years, eighty to eighty-nine years, and ninety years or more)27,28. We combined these age-stratified data to estimate the sex-specific prevalence of primary and revision total knee replacement for individuals fifty years of age and older. For comparison, we similarly estimated the sex-specific prevalence of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis.

Estimating the Number of Adults in the U.S. with Total Knee Replacement

We multiplied estimates of the prevalence of total knee replacement within each ten-year age group by corresponding ten-year population estimates to estimate the number of individuals living with total knee replacement within each age stratum. We separated these results into individuals with primary and revision total knee replacement. We similarly used population estimates in combination with model estimates of the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis to calculate the number of adults in the U.S. who have diagnosed, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis.

Estimating Lifetime Risk of Total Knee Replacement

We used the OAPol Model to calculate the cumulative risk of being diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis and receiving a total knee replacement over the life span, approximated by the time frame between twenty-five and ninety-nine years of age. The cumulative lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis was defined as the proportion of persons who developed symptomatic knee osteoarthritis over their lifetime. Lifetime risk of total knee replacement was defined as the proportion of adults in the U.S. who were diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis over the course of their lifetime and subsequently underwent total knee replacement.

Source of Funding

This project was supported in part by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health grants R01 AR053112 and K24 AR057827. These funding sources did not play any role in the design or reporting of the study.

Results

Prevalence of Total Knee Replacement

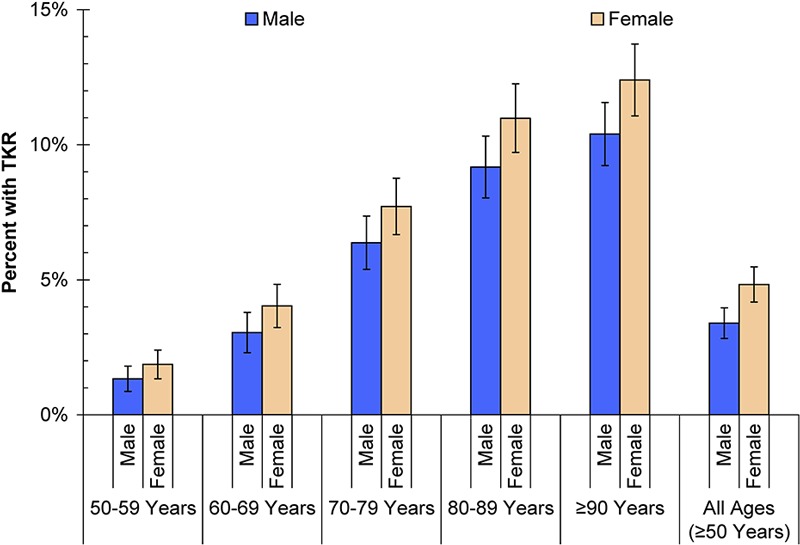

We estimated the overall prevalence of total knee replacement among adults in the U.S. fifty years of age or older to be 4.2% (95% CI: 3.7% to 4.6%). The prevalence was higher among females (4.8%) than males (3.4%), and the prevalence increased with each decade of age (Fig. 1). Among males, the prevalence of total knee replacement ranged from 1.3% among those from fifty to fifty-nine years old to >9% among those eighty years of age or older. Among females, the prevalence ranged from 1.9% among those from fifty to fifty-nine years old to >11% among those eighty years of age or older.

Fig. 1.

Estimated prevalence of total knee replacement (TKR) in the U.S. by age and sex. Each bar represents the percent of the population with total knee replacement, stratified by age group (increasing from left to right) and sex (blue for male and orange for female). The error bars around each prevalence estimate represent 95% confidence intervals.

Among adults in the U.S. fifty years of age or older, 11.5% had been diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. The percent of adults in the U.S. who had been diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis was higher among females (13.3%) than males (9.4%).

Number of Adults in the U.S. Living with Total Knee Replacement

We estimated that 4,007,400 adults (95% CI: 3,583,400 to 4,431,400 adults) in the U.S. over the age of fifty years currently live with a total knee replacement. Of those, 1,505,900 are male and 2,501,500 are female. Furthermore, we calculated that, of those currently alive with a total knee replacement, 3,471,300 individuals have an intact primary total knee replacement and 536,100 have a revised total knee replacement.

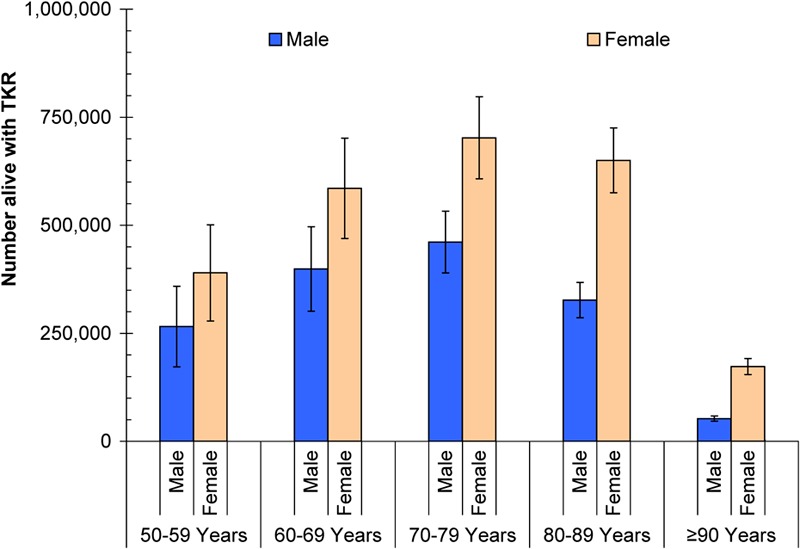

Currently, 265,900 males and 389,900 females from fifty to fifty-nine years old, and another 399,100 males and 585,600 females from sixty to sixty-nine years old, are living with a total knee replacement (Fig. 2). Combining these two age groups, 1,462,200 adults from fifty to sixty-nine years old have an intact primary total knee replacement and 178,300 have a revised total knee replacement. The highest number of individuals with a total knee replacement was found in the seventy to seventy-nine-year-old group (461,000 males and 702,500 females).

Fig. 2.

Estimated number of adults in the U.S. living with total knee replacement by age and sex. Each bar represents the number of adults with total knee replacement (TKR), stratified by age group (increasing from left to right) and sex (blue for male and orange for female). The error bars around each estimate represent 95% confidence intervals.

Similar OAPol Model projections found that 11,059,800 adults in the U.S. (including those with total knee replacement) are currently diagnosed as having symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Of the individuals with osteoarthritis, 6,876,700 are female and 4,183,100 are male. We estimated that 31.6% of males and 31.3% of females who are alive and have been diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis have an intact primary total knee replacement. An additional 4.4% of males and 5.1% of females who have been diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis have a revision total knee replacement.

Lifetime Risk of Total Knee Replacement

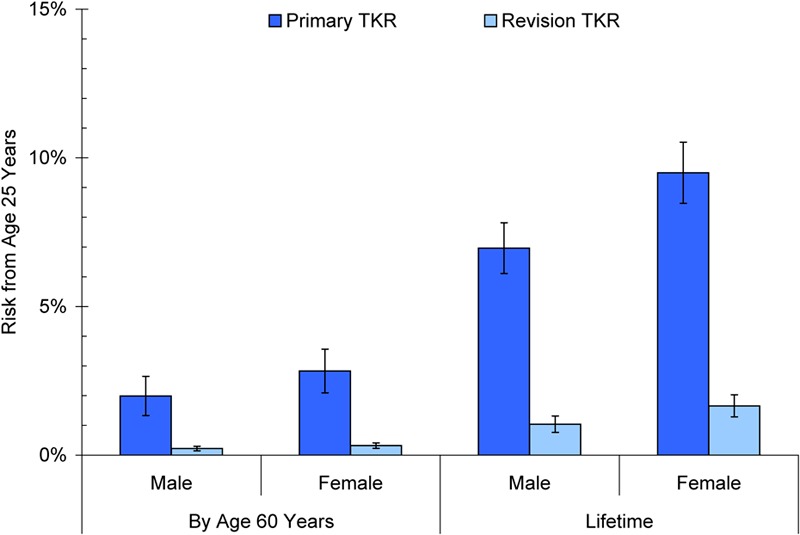

The risk of a twenty-five-year-old adult being diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis by the age of sixty years was 8.3% for males and 11.5% for females. The risk of undergoing a primary total knee replacement by the age of sixty years was 2.0% (95% CI: 1.3% to 2.6%) for males and 2.8% (95% CI: 2.1% to 3.6%) for females (Fig. 3). The risk of revision total knee replacement by the age of sixty years was <0.4% for both males and females. The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis was 13.3% for males and 18.8% for females. The lifetime risk of receiving a primary total knee replacement was 7.0% (95% CI: 6.1% to 7.8%) for males and 9.5% (95% CI: 8.5% to 10.5%) for females, and the lifetime risk of undergoing revision total knee replacement surgery was 1.0% (95% CI: 0.8% to 1.3%) for males and 1.7% (95% CI: 1.3% to 2.0%) for females.

Fig. 3.

Estimated risk of primary and revision total knee replacement from the age of twenty-five years by sex. Each bar represents the percent chance that a twenty-five-year-old male or female will undergo total knee replacement (TKR) by the age of sixty years (left two sections) or within his or her lifetime (right two sections). The darker blue bars represent the risk of undergoing a primary total knee replacement, and the lighter blue bars represent the risk of undergoing a revision total knee replacement. The error bars around each estimate represent 95% confidence intervals.

On the basis of our estimates, 52.2% of males and 50.6% of females who are diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis will receive a primary total knee replacement before death. Among those who undergo a primary total knee replacement, the risk of subsequent revision is 14.9% for males and 17.4% for females.

Sensitivity Analysis

In sensitivity analyses, in which we did not reduce the estimates of the annual incidence of total knee replacement for persons less than forty-five years old and those eighty-five years or older, model estimates of the number of adults living with total knee replacement did not increase by >5%. Increasing and decreasing all age and sex-specific total knee replacement incidence values by 25% led to a range in the prevalence of total knee replacement among adults in the U.S. fifty years of age or older from 3.7% to 4.6%. Estimates of the number of adults in the U.S. living with a total knee replacement ranged from 3,538,700 to 4,446,700. Estimates of the lifetime risk of undergoing primary total knee replacement ranged from 6.3% to 7.5% for males and from 8.7% to 10.2% for females. The lifetime risk of revision total knee replacement ranged from 0.9% to 1.2% for males and from 1.4% to 1.9% for females.

Discussion

We estimated that 4.8% of females and 3.4% of males in the U.S. who are more than fifty years old are currently living with a total knee replacement. This translates to an estimated four million adults in the U.S. with a knee implant, including >500,000 who have undergone revision of the primary total knee replacement. The number of individuals with a total knee replacement represents over one-third of the estimated eleven million adults in the U.S. currently alive who have been diagnosed with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis.

Our model-based estimates suggest that total knee replacement is highly prevalent among older adults in the U.S. Among persons older than fifty years of age, total knee replacement has become considerably more prevalent than rheumatoid arthritis29 and nearly as prevalent as congestive heart failure30. Such comparisons are limited because total knee replacement is not a chronic disease. However, similar to living with a chronic condition, undergoing elective surgery and living with a prosthetic implant lead to increased health-care utilization and carry small but clearly defined health risks, including joint infection, periprosthetic fracture, symptomatic implant loosening, and implant wear11. While annual rates of these adverse outcomes are low, with millions of adults in the U.S. living with total knee replacement over a prolonged period, these complications pose a potentially large public health burden.

Given the frequency of total knee replacement utilization, failed total knee replacements represent a sizeable public health problem. One report has noted that as many as 15% of total knee replacement recipients may experience severe or extreme persistent pain three to four years postoperatively31. These patients often continue to require higher levels of health-care utilization and to experience the disability and reduced quality of life associated with osteoarthritis-related knee pain. Because of their continued disability, individuals with pain after total knee replacement may have low levels of physical activity and be at a heightened risk of death due to other comorbidities compared with the general population32. Moreover, patients with osteoarthritis who have a total knee replacement may experience pain of a type that is more difficult to diagnose and treat than that in patients without a total knee replacement11,33. Given that total knee replacement recipients represent over one-third of adults in the U.S. with diagnosed, symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, refining diagnostic and treatment algorithms should be a priority.

The estimated public health-care burden of total knee replacement is amplified by the fact that nearly 1.5 million adults in the U.S. with an intact primary total knee replacement are between the ages of fifty and sixty-nine years. The existence of this large cohort of young individuals with a total knee replacement is consistent with data suggesting that total knee replacement use has tripled within the forty-five to sixty-four-year-old age group over the past ten years5. With recent studies suggesting that younger, healthier patients experience better postoperative outcomes34-36, patients wishing to achieve the maximum clinical benefit may be offered and elect total knee replacement at an earlier age. Many of the 1.5 million adults in the U.S. with a total knee replacement will survive for fifteen to twenty years postoperatively, giving them prolonged exposure to complications that may lead to a costly revision arthroplasty. Furthermore, recent data suggest that annual rates of revision for aseptic failure are higher for younger recipients of total knee replacement than for those who are older at the time of surgery6,37. Such findings may indicate that younger individuals, wishing to maintain higher levels of physical activity after surgery, may impose more stress on their knee implants, leading to faster wear rates. The complex role of physical activity, both in improving outcomes after total knee replacement and in increasing the likelihood of complications that may lead to revision, merits further investigation.

The high prevalence of total knee replacement points out the necessity of increasing efforts to prevent osteoarthritis, likely by targeting osteoarthritis risk factors such as obesity and knee injury38,39. Reducing the nationwide prevalence of obesity to levels seen ten years ago could avert >100,000 total knee replacements over the remaining life span for adults in the U.S. who are fifty to eighty-four years old19.

Our methods of estimating the prevalence and lifetime risk of total knee replacement have several limitations. We estimated the annual incidence of total knee replacement using data from longitudinal osteoarthritis cohorts, which, due to strict selection criteria, may not be representative of the U.S. population with knee osteoarthritis40. For example, individuals were excluded from participating in the OAI if they were considering undergoing total knee replacement within the next three years, possibly leading to lower incidence of total knee replacement among the OAI cohort than among the general U.S. population with end-stage knee osteoarthritis. Consequently, we used data from the MOST study, which did not impose such a restriction, to estimate the magnitude of our incidence estimates and then used data from the OAI study to stratify these estimates by age and sex.

Furthermore, our modeling approach required that we use constant age and sex-specific incidence estimates, although, in reality, the use of total knee replacement among those with end-stage knee osteoarthritis may have changed over time. Data from the OAI and MOST studies were collected in the early 2000s, whereas some individuals currently living with total knee replacement underwent the procedure before the early 2000s, when total knee replacement use was less common12,15. On the other hand, our incidence estimates may be conservative for individuals who underwent total knee replacement in recent years, as the utilization of the procedure has continued to climb since the early 2000s5. We accounted for potential variation in total knee replacement incidence over time by performing sensitivity analyses, in which total knee replacement incidence was increased and decreased by 25% across all ages. Even accounting for drastic variation in this pivotal input parameter, estimates of the prevalence of total knee replacement were still approximately 4% to 5% and the number of adults in the U.S. with a total knee replacement remained close to four million. Thus, assuming constant age and sex-specific values of total knee replacement incidence in our modeling approach may not drastically affect the resulting estimates of the current total knee replacement burden in the U.S. Our estimates of the current prevalence and lifetime risk of total knee replacement do not take into consideration future trends in total knee replacement utilization. Some projections have estimated total knee replacement use will continue to grow rapidly in the coming years13,41. On the other hand, our estimates suggest that over one-third of people who have been diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis in the U.S. have already received a total knee replacement, potentially indicating that, due to high market saturation, the rapid increase in total knee replacement utilization over the last decade4 may not be sustained in future years.

Our estimates suggest that total knee replacement is a prevalent condition among adults in the U.S. that may pose a high public health burden. Individuals who have undergone total knee replacement are at risk for several costly and debilitating outcomes, including periprosthetic fracture and joint infection, and are at risk for revision surgery. These outcomes may require specific health services, and knowledge of the number of people who currently live with a total knee replacement is valuable in planning prevention and management strategies. While total knee replacement is a remarkably successful treatment for individuals with end-stage knee osteoarthritis, our findings emphasize the large public health burden posed by the millions of adults in the U.S. living with total knee replacement.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Footnotes

Disclosure: One or more of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of an aspect of this work. In addition, one or more of the authors, or his or her institution, has had a financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this work, with an entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. No author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the article.

References

- 1.American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(9):1905-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richmond J, Hunter D, Irrgang J, Jones MH, Snyder-Mackler L, Van Durme D, Rubin C, Matzkin EG, Marx RG, Levy BA, Watters WC, 3rd, Goldberg MJ, Keith M, Haralson RH, 3rd, Turkelson CM, Wies JL, Anderson S, Boyer K, Sluka P, St Andre J, McGowan R; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(4):990-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, Abramson S, Altman RD, Arden NK, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt KD, Croft P, Doherty M, Dougados M, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kwoh K, Lohmander LS, Tugwell P. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(4):476-99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 1999-2009. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed 2012 Jan 3

- 5.Losina E, Thornhill TS, Rome BN, Wright J, Katz JN. The dramatic increase in total knee replacement utilization rates in the United States cannot be fully explained by growth in population size and the obesity epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(3):201-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paxton EW, Namba RS, Maletis GB, Khatod M, Yue EJ, Davies M, Low RB, Jr, Wyatt RW, Inacio MC, Funahashi TT. A prospective study of 80,000 total joint and 5000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction procedures in a community-based registry in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(Suppl 2):117-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callahan CM, Drake BG, Heck DA, Dittus RS. Patient outcomes following tricompartmental total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1994;271(17):1349-57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz JN, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Barrett JA, Fossel AH, Creel AH, Wright J, Wright EA, Losina E. Association of hospital and surgeon procedure volume with patient-centered outcomes of total knee replacement in a population-based cohort of patients age 65 years and older. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(2):568-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright RJ, Losina E. Association between hospital and surgeon procedure volume and the outcomes of total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(9):1909-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh JA, Jensen MR, Harmsen WS, Gabriel SE, Lewallen DG. Cardiac and thromboembolic complications and mortality in patients undergoing total hip and total knee arthroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(12):2082-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seil R, Pape D. Causes of failure and etiology of painful primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1418-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain NB, Higgins LD, Ozumba D, Guller U, Cronin M, Pietrobon R, Katz JN. Trends in epidemiology of knee arthroplasty in the United States, 1990-2000. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(12):3928-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(10):2606-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehrotra C, Remington PL, Naimi TS, Washington W, Miller R. Trends in total knee replacement surgeries and implications for public health, 1990-2000. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(3):278-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh JA, Vessely MB, Harmsen WS, Schleck CD, Melton LJI, 3rd, Kurland RL, Berry DJ. A population-based study of trends in the use of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, 1969-2008. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(10):898-904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI). University of California San Francisco; 2010. http://oai.epi-ucsf.org/datarelease/default.asp. Accessed 2012 Jan 3.

- 17.Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST) University of California San Francisco; 2010. http://most.ucsf.edu/. Accessed 2012 Jan 3.

- 18.Holt HL, Katz JN, Reichmann WM, Gerlovin H, Wright EA, Hunter DJ, Jordan JM, Kessler CL, Losina E. Forecasting the burden of advanced knee osteoarthritis over a 10-year period in a cohort of 60-64 year-old US adults. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(1):44-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losina E, Walensky RP, Reichmann WM, Holt HL, Gerlovin H, Solomon DH, Jordan JM, Hunter DJ, Suter LG, Weinstein AM, Paltiel AD, Katz JN. Impact of obesity and knee osteoarthritis on morbidity and mortality in older Americans. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Feb 15;154(4):217-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2005-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Data. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2005-2006/nhanes05_06.htm. Accessed 2012 Jan 3.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2007-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Data. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2007-2008/nhanes07_08.htm. Accessed 2012 Jan 3.

- 22.Burbine SA, Weinstein AM, Reichmann WM, Rome BN, Collins JE, Katz JN, Losina E. Projecting the future public health impact of the trend toward earlier onset of knee osteoarthritis in the past 20 years. Read at the American College of Rheumatology Annual Scientific Meeting; 2011 Nov 4-9; Chicago, IL.

- 23.Wise BL, Felson DT, Clancy M, Niu J, Neogi T, Lane NE, Hietpas J, Curtis JR, Bradley LA, Torner JC, Zhang Y. Consistency of knee pain and risk of knee replacement: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1390-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reichmann WM, Gagnon D, Horsburgh CR, Losina E. Evaluation of exposure-specific risks from two independent samples: a simulation study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 1975-1997: an update with special emphasis on 41,223 knees operated on in 1988-1997. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):503-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garvin KL, Hartman CW, Mangla J, Murdoch N, Martell JM. Wear analysis in THA utilizing oxidized zirconium and crosslinked polyethylene. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(1):141-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Census Bureau. Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic origin. 2009. http://www.census.gov/popest/data/national/asrh/2009/index.html. Accessed 2012 Jan 3.

- 28. United States Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Bridged-Race Population Estimates, United States July 1st resident population by age and sex, on CDC WONDER On-line Database. 2009. http://wonder.cdc.gov/Bridged-Race-v2009.HTML. Accessed 2012 Jan 3.

- 29.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH; National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massie BM, Shah NB. Evolving trends in the epidemiologic factors of heart failure: rationale for preventive strategies and comprehensive disease management. Am Heart J. 1997;133(6):703-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: prevalence, sensory qualities, and postoperative determinants. Pain. 2011;152(3):566-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nüesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S, Williams S, Iff S, Jüni P. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann S, Seitlinger G, Djahani O, Pietsch M. The painful knee after TKA: a diagnostic algorithm for failure analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(9):1442-52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.SooHoo NF, Lieberman JR, Ko CY, Zingmond DS. Factors predicting complication rates following total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(3):480-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortin PR, Penrod JR, Clarke AE, St-Pierre Y, Joseph L, Bélisle P, Liang MH, Ferland D, Phillips CB, Mahomed N, Tanzer M, Sledge C, Fossel AH, Katz JN. Timing of total joint replacement affects clinical outcomes among patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(12):3327-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB; Kinemax Outcomes Group Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(10):2179-86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Julin J, Jämsen E, Puolakka T, Konttinen YT, Moilanen T. Younger age increases the risk of early prosthesis failure following primary total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. A follow-up study of 32,019 total knee replacements in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(4):413-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Simpson JA, Wluka AE, Teichtahl AJ, English DR, Giles GG, Graves S, Cicuttini FM. Is physical activity a risk factor for primary knee or hip replacement due to osteoarthritis? A prospective cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(2):350-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wills AK, Black S, Cooper R, Coppack RJ, Hardy R, Martin KR, et al. Life course body mass index and risk of knee osteoarthritis at the age of 53 years: evidence from the 1946 British birth cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;Epub Oct 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reichmann WM, Katz JN, Losina E. Differences in self-reported health in the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) and Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-III). PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest