Abstract

Objective

To conduct a meta-analytic review of HIV interventions for heterosexual African Americans to determine the overall efficacy in reducing HIV-risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and identify intervention characteristics associated with efficacy.

Methods

Comprehensive searches included electronic databases from 1988 to 2005, handsearches of journals, reference lists of articles, and contacts with researchers. Thirty-eight randomized controlled trials met the selection criteria. Random-effects models were used to aggregate data.

Results

Interventions significantly reduced unprotected sex (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.67, 0.84, 35 trials, N = 14,682) and marginally significantly decreased incident STD (OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.72, 1.07, 10 trials, n = 10,944). Intervention characteristics associated with efficacy include: (1) culturally tailored, (2) aiming to influence social norms in promoting safe sex behaviour, (3) utilizing peer education, (4) providing skills training on correct use of condoms and communication skills needed for negotiating safer sex, and (5) multiple sessions and opportunities to practice learned skills.

Conclusion

Interventions targeting heterosexual African Americans are efficacious in reducing HIV-risk sex behaviors. Efficacious intervention components identified in this review should be incorporated into the development of future interventions and further evaluated for effectiveness.

Keywords: HIV/STD prevention, behavioral intervention, condom use, sexually transmitted diseases, African-American, Heterosexual, Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

African-American heterosexuals are disproportionately impacted by HIV [1, 2]. A myriad of factors has been suggested for this finding, ranging from limited access to health care to the broader societal repercussions of racism and poverty. The impact of the HIV epidemic among African Americans underscores the importance of identifying efficacious behavioral interventions to reduce the risk of acquiring HIV via sexual behavior. Numerous interventions targeting sexual risk reduction among African-American heterosexuals have been evaluated in recent years; however, the empirical findings have not been examined as a whole. While several meta-analyses have been conducted to examine the efficacy of HIV behavioral interventions for various populations at risk for HIV infection, including men who have sex with men [3, 4, 5], women [6, 7], heterosexual men [8], drug users [9, 10] adolescents [11, 12], Hispanics [13] and sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinic patients [14, 15], there is no meta-analysis that provides the overall assessment of intervention efficacy specifically for heterosexual African Americans.

Aside from estimating the overall intervention efficacy, meta-analysis can also identify particular factors (i.e., study design, intervention features) that are associated with intervention efficacy. Qualitative systematic reviews have focused on components of HIV prevention strategies for African Americans specifically [16, 17, 18, 19], women of color [20], and culturally competent interventions [21]. All of the reviews recommended including cultural tailoring specific to the community of interest.

To make empirically driven evidence-based recommendations for programmatic efforts and future research, we conducted a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials (RCT) that evaluated HIV behavioral interventions for African-American heterosexual populations in the U.S. We restricted this review to only RCTs following the Cochrane Collaboration principles, which recommend focusing on RCTs for synthesizing clinical and behavioral research findings and providing the best evidence as to intervention efficacy [22]. Given methodological issues, we restricted our analyses to individual-level and group-level interventions. Our specific goals included assessing the overall efficacy of interventions in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV among African Americans regardless of drug using status, identifying characteristics of the studies, samples and interventions that are associated with intervention efficacy, and highlighting research gaps for this population.

METHODS

Data source

As part of CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) project [23, 24], we developed multiple search strategies to identify published and unpublished RCTs evaluating interventions to reduce HIV sex risk behaviors among African-American heterosexuals between 1988 and 2005. We developed an automated systematic search using standardized search terms cross-referenced in three areas: (a) HIV, AIDS, or STD; (b) intervention evaluation; and (c) behavior or biologic outcomes. We searched multiple electronic bibliographic databases including AIDSLINE (1988 to 2000), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts from 1988 to 2005. For each database, we searched unique index terms supplemented with keywords and phrases. We also manually searched 35 key journals, which regularly publish HIV or STD prevention research, to locate additional reports for the time period January 2004 to December 2005 and checked reference lists of pertinent reports to identify additional reports. Finally, we contacted researchers and research organizations for current and on-going research. Complete descriptions of the search strategies and terms are available on request.

Trial selection

Relevant studies were included in this review if they met all of the following criteria:

Evaluated individual-level or group-level interventions specifically designed to change risky sex behaviors in efforts to decrease the risk of heterosexual transmission of HIV.

Employed an RCT design.

Focused on or specifically targeted African Americans, or consisted of at least 80% African-American participants.

Were conducted in the United States.

- Measured any of the following sex risk behavior and biologic variables:

- any unprotected insertive or receptive anal intercourse, unprotected vaginal insertive or receptive intercourse,

- consistency of condom use, or

- incident STD.

Reported at least one post-intervention outcome.

Reported sufficient descriptive data or statistical tests of the intervention effects necessary to calculate an effect size. We contacted authors to obtain additional information as needed.

Data extraction

Trained pairs of reviewers independently abstracted information from eligible reports. We identified linkages among reports to ensure that multiple reports describing an intervention were included in the coding and data analysis. We coded each intervention using a standardized coding form for trial information (e.g., intervention dates, location), participant characteristics (e.g., age, gender), outcomes (type of outcome, follow-up time, STD measurement and assays [see Appendix available online]), and intervention features (theory-based, delivery method). We coded for specific features for culturally tailored interventions such as statements of cultural appropriateness, ethnically matched deliverer, and ethnographic research. We assessed the methodological quality of the studies by assessing randomization (sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding), type of control group, participation rate, overall and differential retention rate, power analysis, and intent-to-treat analysis based on the modified Jadad criteria for RCTs [25]. There was a 90% agreement between reviewers across variables. We reconciled coding discrepancies through discussion.

Analytic approach

Because studies differed in terms of the number of arms, type of outcomes, analyses conducted, and findings reported, we used the following rules for abstracting information for meta-analysis. To meet the independence of the effect size assumption, for trials with multiple arms we selected the contrast between the intervention arm that was most theoretically potent and the comparison arm, which was typically a standard of care or wait list control. Separate analyses were conducted for sex outcomes and laboratory/clinical diagnosis of incident STDs. To prevent the correlations from multiple effect size estimates within a single study from biasing the results, we selected unprotected sex over condom use for studies that reported both measures. If a trial reported outcome data at two or more follow-ups, we selected the first follow-up for the overall effect size. Finally, to ensure non-equivalent groups at baseline did not confound the results, we adjusted for baseline sexual behavior differences if the information was available [26, 27].

Meta-analytic methods

We used odds ratios (OR) to present the magnitude of intervention effects. For trials reporting means and standard deviations on continuous outcomes, we calculated standardized mean differences and then converted into ORs [4]. We used standardized meta-analytical methods [27, 28] to calculate individual effect size and combine effect sizes across studies. We used the natural logarithm to obtain log odds ratios (lnOR) and calculated its corresponding weight (inverse variance) for each study. In estimating the overall effect size, we multiplied each lnOR by its weight, summed the weighted lnORs across trials and then divided by the sum of the weights. We then converted the aggregated lnOR back to OR and derived a 95% confidence intervention (95% CI). We also examined the heterogeneity of the effect sizes by using the Q statistic. We tested both fixed-effects and random-effects models, and both models yielded similar findings. We base the final presentation on the random-effects model because it provides a more conservative estimate of variance and generates more accurate inferences about a population of trials beyond the set of trials included in this review [29].

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine the robustness of intervention effects and stratified analyses to determine whether methodological quality, trial and sample characteristics, or intervention features were associated with effect sizes. We assessed the likelihood of subgroup differences using the between groups’ heterogeneity statistics, QB, which has a χ2 distribution and degree of freedom equal to the number of subgroups minus 1 degree of freedom. We used all the available data and recalculated the overall effect size separately for trials reporting unprotected sex and trials reporting condom use. We examined intervention effects on the sex outcomes at the following follow-up times: less than 3 months, 3 months, 6 months, and longer than 6 months. Similar analyses were conducted for the STD outcomes at 6-month and 12-month post intervention. In addition, we compared the aggregated effect size estimate among all trials with the estimate obtained after excluding trials that might influence the overall estimate.

We ascertained publication bias by inspection of a funnel plot [30] and a linear regression test [31], which compared standardized effect size estimate with precision (the inverse of the standard error) of each study.

RESULTS

Description of trial, sample, and intervention characteristics

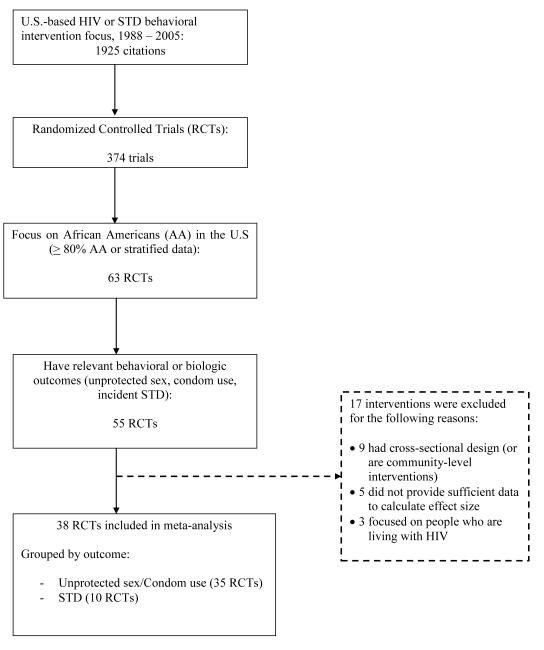

Thirty-eight RCTs, including 14,983 participants, met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Descriptive information for each trial is shown in Table 1 (available online) [32-69], and summary information of intervention components and design is presented in Table 2. Participants in the majority of the trials included either women only or mixed gender; non-drug users; and over 18 years old. Approximately half of the trials were set in clinics, while half were conducted in either community or educational/research settings.

Figure 1.

Trial Selection Process for Meta-Analytic Review of HIV Prevention Interventions for African-American Heterosexuals

Table 1.

Description of 38 Randomized Controlled Trails of HIV Prevention Interventions with African-American Heterosexuals.

| Study | Sample size and description |

Setting | Study groups | Intervention description (components, duration, time span, theory) |

Unit of delivery |

Assessment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen. (1996) | 421; 95% African- American 72% male Detroit, MI |

Other | 1 comparison group (standardized intervention, HIV related) 1 intervention group (standard int. + enhanced intervention) |

Both comparison and intervention group received: Information, skills training (technical), referrals, risk reduction materials, HIV counseling and testing, perceived risk) Intervention group received components listed above plus: Counseling, emotional support, culturally tailored Intervention (5 sessions + support group) 40 minutes, 14 weeks Theory: Health Belief Model |

Individual | Immediate + 6 month follow-up |

Unprotected sex |

| Branson (1998) | 964; 90% African- American 57% male Houston, TX |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (standardized intervention, HIV-related) 1 intervention group (standardized int. + enhanced) |

Both comparison and intervention group received: Information Only Comparison group received: Counseling Intervention group received: Information, Skills training (technical and personal), motivation, perceived risk, self esteem, Intervention (4 group sessions + booster group) 50 minutes, 8 weeks Theory: Information-Motivation- Behavior |

Group | Immediate and 6 month follow-up |

Condom use |

| Carey (2000) | 102; 88% African- American 100% female Syracuse, NY |

Com- munity setting |

1 control group (Non-HIV attention control) 1 intervention group |

Both control group and intervention group received: Information Control group received: Skills training (technical, personal) Intervention group received: Information, skills training (interpersonal), counseling, increase motivation Intervention (4 sessions), 90 minutes, 2 weeks Theory: Unclear |

Group | 3-month follow-up |

Condom use |

| Cottler (1998) | 605; 93% African- American 61% male St. Louis, MO |

Clinic setting |

1 control group (standard intervention, included HIV counseling and testing) 1 tx group (standard int. + enhanced) |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, skills training (technical), referrals, risk reduction materials, HIV counseling and testing Intervention group received above plus: Peer education, counseling, Intervention (4 sessions, 120 minutes) Theory: None |

Individual | 3-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Dancy (2000) | 280; 100% African - American; 100% female Chicago, IL |

Un- specified setting |

1 control group (Non-HIV attention control) 1 tx group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information Comparison group received: information, skills training (technical) Intervention group received: information, peer education, skills training (interpersonal), social norms, attitude, improve self-efficacy, perceived risk, culturally tailored Intervention (6 90-minute sessions followed by 3 booster sessions) Theory: Social Cognitive Theory, Theory of Reasoned Action, Health Belief Model |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| DeLamater (2000) | 312; 100% African- American; 100% male unspecified city |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 tx group |

Both comparison and intervention group received: information, risk reduction materials, counseling Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical), beliefs and intentions, perceived risk, self efficacy, culturally tailored Intervention (1 14 minute session) Theory: Self-regulation model of illness behavior |

Individual | 6-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| DiClemente (1995) | 93; 100% African- American; 100% female San Francisco, CA |

Com- munity setting |

1 wait list control 1 tx group |

Intervention group received: Information, Peer education, skills training (technical, interpersonal), emotional support, social norms, empowerment, culturally tailored Intervention (5 sessions, 120 minutes each), 5 weeks Theory: Social Cognitive Theory, Gender and power |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| DiClemente (2004) | 522; 100% African- American 100% female |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (General Health Promotion) 1 intervention group |

Intervention group received: Information, peer education, skills training (), self-efficacy, perception of risk, empowerment, culturally tailored Intervention (4 session, 4 hours each), 4 weeks Theory: Social cognitive theory, Gender and power |

Group | 6-month follow- up |

Condom use/partner |

| Ehrhardt (2002) | 360; 72% African- American 100% female |

Un- specified setting |

1 control group (no intervention) 1 comparison group (4 sessions) 1 intervention group (8 sessions) |

Intervention group received: Information, Skills training, motivation, attitudes, beliefs and intentions, perceptions of risk, empowerment Intervention (4 vs. 8 sessions, 2 hours each) 8 session group received 1 topic per session for 8 topics, 4 session group received 2 topics each session on same 8 topics Theory: Modified AIDS Risk Reduction Model, Social learning theory |

Group | 6-month follow- up |

Condom use (male + female) |

| Gollub (2000) | 292; 91% African- American 100% female Philadelphia, PA |

Clinic setting |

2 comparison groups (HIV- related) (1 session) 1 intervention group (1 session) |

All groups received: information, HIV testing and counseling, risk reduction materials and skills training Comparison groups received risk reduction for either only male condoms or only female condoms. Intervention group received “hierarchical risk reduction” incorporating both female and male condoms as well as other barrier methods and spermicides. Theory: Feminist |

Majority Group (35% counseled individually ) |

4-month follow- up 6-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Harris (1998) | 204; 100% African- American; 100% female Baltimore, MD |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (standard methadone tx) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: Information, skills training (personal), counseling, emotional support Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (interpersonal), empowerment, motivation, self-esteem, Intervention (16 sessions, 120 minutes for 8 weeks, 60 minutes for 8 weeks), over 16 weeks Theory: :Leininger’s prevention framework |

Group | 5-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Jemmott (1992) | 157; 100% African- American 100% male Philadelphia, PA |

Educa- tional setting |

1 control group (attention control) 1 intervention group |

Both control group and intervention group received: information Intervention group received information plus: Skills training (interpersonal, technical), influencing attitudes, beliefs and intentions, culturally tailored Intervention (1 session, 5 hours) Theory: Social Cognitive, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Jemmott (1998) | 432; 100% African- American 47% male Philadelphia, PA |

Educa- tional setting |

1 control group (attention control) 1 intervention group |

Both control and intervention group received information and peer education, Control group only received: motivation Intervention group received: information, peer education, skills training (interpersonal), attitude, beliefs and intentions, self-efficacy, culturally tailored Intervention (8 sessions, 1 hour each) over 2 weeks Theory: Social Cognitive, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Jemmott (1999) | 496; 100% African- American 46% male Philadelphia, NJ |

Educa- tional setting |

1 comparison group (non -HIV, health promotion) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, interpersonal), attitudes, beliefs and intentions, self-efficacy, culturally tailored Intervention (1 session, 5hours) 1 day Theory: Social Cognitive, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Kalichman (1996) | 128?; 100% African- American 100% female Milwaukee, WI |

Un- specified setting |

1 comparison group (HIV related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison and intervention group received: information, perceived risk Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, interpersonal), self-efficacy, culturally tailored Intervention (4 sessions, no information regarding session duration), 2 weeks Theory: Social Learning Theory, Cognitive Behavioral principles |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Kalichman (1999a) | 108?; 100% African- American 100% male Unspecified city |

Com- munity setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group (check on this) |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, risk reduction materials Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, personal), motivation, culturally tailored Intervention (1 session, 3 hours) Theory: Information-Motivation- Behavior |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Kalichman (1999b) | 117; 100% African- American 100% male Atlanta, GA |

Com- munity setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison and intervention group received: information, risk reduction materials, motivation, attitudes Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, personal, interpersonal), culturally tailored Intervention (2 sessions, 3 hours each, over 3 days) Theory: Information-Motivation- Behavior |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Kalichman (2005) | 612; 85% African- American 69% male Milwaukee, WI |

Clinic setting |

3 comparison groups (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

1 Comparison group received: information 1 comparison group received: information, motivation 1 comparison group received: information, skills training (interpersonal, technical) Intervention group received: information, motivation, skills training (interpersonal, technical) Theory: Information-Motivation- Behavior |

Individual | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Kamb (1998) | 5758: 59% African- American 43% female Baltimore, MD, Denver, CO, Long Beach, CA, Newark, NJ, San Francisco, CA |

Clinic setting |

2 comparison groups (HIV- related) (1 group participated in follow-up visits, one did not_ 2 intervention groups (1 standard, 1 enhanced) |

Comparison groups received: Information, HIV-testing and counseling (10 minutes over 2 sessions) Standard intervention group received: Counseling, HIV-testing and counseling, information, perception of risk (40 minutes over 2 sessions) Enhanced intervention group received: Counseling, HIV-testing and counseling, information, self-efficacy, attitudes, intentions, beliefs (200 minutes over 4 sessions, 1st session 20 minutes, 60 minutes thereafter) Theory: Theory of reasoned action, social cognitive theory |

Individual | 3-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Kelly (1994) | 187; 87% African- American (separate analysis for AA participants) 100% female Milwaukee, WI |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (non HIV-related, family and child health) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison and intervention group received: information Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, interpersonal), social norms, attitude, beliefs and intentions Intervention (5 sessions, 4 90-minute sessions in 4 consecutive weeks, 1 at 1 month follow-up) Theory: Theory of Reasoned Action, AIDS Risk Reduction Model |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Kennedy (2000) | 115; 100% African- American 41% male Nashville, TN |

Com- munity setting |

1 wait-list control 1 intervention group |

Intervention group received: Information, skills training (interpersonal), attitude, beliefs and intentions Intervention (1 session, 7 hours) Theory: Theory of Reasoned Action |

Group | 1-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Latkin (2003) | 250; 94% African- American 61% male Baltimore, MD |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

Comparison group received: information, (10 sessions, 90 minutes each, only 1st session was HIV-related) Intervention group received: information, skills training, referrals, risk reduction materials, motivation, self-efficacy, (10 sessions, 90 minutes each) Theory: Social Cognitive theory, Social influence, harm reduction |

Group (para- professional male and female indigenous facilitators) |

6-month follow- up |

Condom use (casual and main partners) |

| Maher (2003) | 581; 100% African- American 100% male Miami, FL |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

Comparison group received routing STD counseling Intervention group received: 3 enhanced counseling sessions (1 hour each): information, skills training, referrals, social norms, perception of risk, motivation, empowerment, attitudes, beliefs, intentions, culturally tailored |

Individual | Passive follow- up (examined clinic records for STD re- infection) |

STD reinfection |

| Malow (1994) | 152; 100% African- American 100% male New Orleans, LA |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, interpersonal), emotional support) Intervention (3 sessions, 1 hour each over 3 days) Theory: AIDS Risk Reduction Model |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Mansfield (1993) | 90; 83% African- American 8% male Unspecified city |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (standard intervention, HIV-related) 1 intervention group (standard care + enhanced) |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, referrals, counseling Intervention group received above plus: perceived risk Intervention (1 30-minute session) Theory: None |

Individual | 2-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| McCoy (1996) | 185; 100% African- American; 100% male Miami, FL |

Un- specified setting |

1 comparison group (Standardized intervention, HIV-related) 1 intervention group (standardized int. + enhanced) |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, skills training (technical), referrals, risk reduction materials, HIV counseling and testing, counseling, perceived risk Intervention group received above plus: skills training (interpersonal), emotional support culturally tailored Intervention group 3 sessions (Control group 2 sessions—included HIV counseling and testing); No information on duration/time span of sessions |

Group | 6 month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| McCoy (1990) | 237?; 92% African- American; 61% male Belle Glade, FL |

Other setting |

1 comparison group (standard intervention, HIV-related) 1 intervention group (standard + enhanced) |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, risk reduction materials, counseling Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (technical, interpersonal) Intervention (3 sessions, no information on length or duration) Theory: Health Belief Model, Theory of Reasoned Action, Conflict Theory |

Group | 6-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Metcalf (2005) | 3342; 51% African- American; 54% male Denver, CO, Long Beach, CA, Newark NJ |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (no booster session following HIV counseling) 1 intervention group (booster session following HIV counseling) |

Comparison group received: no intervention (Had already received standard HIV counseling) Intervention group received: 20 minute booster sessions 6 months after standard HIV counseling, included perception of risk Theory: Booster session reinforced messages in initial counseling sessions, based on cognitive behavioral theories |

Individual (Counselor) |

3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| NIMH (1998) | 2694; 74% African- American ?% male New York, NY; New Jersey, Baltimore, MD; Atlanta, GA |

Un- specified setting |

1 comparison group (HIV related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (interpersonal, personal, technical), motivation, perceived risk, self-efficacy Intervention (7 sessions, between 90- 120 minutes) over 3 weeks Theory: Social Cognitive Theory |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| O’Donnell (1998) | 2004; 62% African- American 100% male New York, NY |

Clinic setting |

2 intervention groups (1 video viewing only 1 video viewing + group discussion) 1 control group (standard STD clinic services) |

Both group and intervention group received: Information Counseling Risk reduction materials Intervention ( 1 session, 20 minutes) Theory: Theory of reasoned action |

Group | Average 18- month follow- up |

STD reinfection |

| O’Leary (1998) | 472; 91% African- American 59% male MD, GA, NJ |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (usual care in STD clinics) 1 intervention group |

Comparison group received: usual care in STD clinics (information, counseling) Intervention group received: information, skills training, self- efficacy, perception of risk 7 90-minute sessions Theory: Social cognitive theory, Theory of reasoned action (as per Jemmott et al., 1992) |

Group (2 trained professional or paraprofess ional facilitators) |

3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Robinson (2002) | 185; 100% African- American 100% female Minneapolis, MN |

Com- munity setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (interpersonal, personal, technical), peer education, emotional support, attitude, beliefs and intentions, empowerment, self-esteem, culturally tailored Intervention (2 sessions, 2 hours each) over 2 days Theory: Sexual Health Model |

Group | 3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Shain (1999) | 617; 31% African- American 100% female San Antonio, TX |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related, wait-list control) 1 intervention group |

Comparison group received: counseling (1 visit, 15 minutes) Intervention group received: counseling, information, skills training, self-efficacy, perception of risk, empowerment, attitudes, beliefs, intentions, (3 weekly sessions, 3-4 hours each) Theory: AIDS Risk Reduction Model |

Group (female facilitator) |

6-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Stanton (1996) | 108; 100% African- American 56% male Unspecified city |

Com- munity setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, risk reduction materials Intervention group received above plus: Skills training (interpersonal), emotional support, culturally tailored Intervention (8 weekly meetings—7 90- minute sessions + 1 day-long sessions, + 6 monthly booster sessions following completion, 1 additional booster session at 15 months post-intervention) Theory: Social Cognitive Theory, Protective-Motivation Theory |

Group | 6-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Sterk (2003) | 71; 100% African- American 100% female Atlanta, GA |

Com- munity setting |

1 comparison group (HIV- related) 2 intervention groups |

All participants received HIV counseling and testing Comparison group received: information, NIDA standard intervention for drug users (2 sessions) Intervention group (enhanced motivation) received: power, control, motivation, information, empowerment (4 sessions) Intervention group (enhanced negotiation) received: information, power, control, motivation, skills training Theory: Social-cognitive theory, Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, transtheoretical model of change, Theory of gender and power |

Individual (trained female interventio n-ists, 1 Caucasian, 1 African- American) |

6-month follow- up |

Condom use |

| Wechsberg (2004) | 620; 100% African- American, 100% female Wake and Durham counties, NC |

Com- munity setting |

1 comparison group 1 standard intervention group 1 enhanced intervention group |

Comparison group: delayed treatment control Standard intervention: NIDA standard prevention intervention (skills training, information, risk reduction materials, HIV counseling and testing 2 individual sessions, 2 group sessions, within 2 weeks Enhanced intervention: empowerment, information, skills training, HIV counseling and testing, risk reduction materials, control, coping skills, referrals, motivation 2 individual sessions, 2 group sessions, within 2 weeks Theory: empowerment theory, African-American feminism |

Individual and group (trained African- American indigenous women) |

3-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Wenger (1991) | 186; 88% African- American 67% male Los Angeles, CA |

Clinic setting |

1 comparison group (standard intervention, HIV-related) 1 intervention group |

Both comparison group and intervention group received: information, counseling Intervention group received above plus: HIV counseling and testing, perceived risk, culturally tailored Intervention (2 sessions, 25 minutes total, over 2 weeks) Theory: None |

Individual | 2-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

| Wu (2003) | 817; 100% African- American 42% male Baltimore, MD |

Com- munity setting |

1 standard intervention (HIV-related) (FOK) 2 intervention: (FOK + ImPACT), (FOK + ImPACT + Booster) |

All groups received (FOK): information, risk reduction materials,skills training (interpersonal), emotional support, culturally tailored (see Stanton, 1996, above) (delivered to adolescent) FOK + ImPACT received: FOK + information, skills training, (delivered to adolescent and parent) FOK + ImPACT + booster received: FOK + ImPACT + booster session (review of previous content, delivered to adolescent) FOK = 8 sessions ImPACT = 1 session Booster sessions (2 boosters/1 session each, delivered at 6- and 10-month follow-up) Theory: social cognitive theory, protection motivation theory |

Group (FOK) Adolescent and parent (ImPACT) Individual (boosters) |

6-month follow- up |

Unprotected sex |

Table 2.

Summary of Sample and Intervention Characteristics of 38 RCTs of HIV Prevention Interventions in African-American Heterosexuals

| Overall: | K = 38, N = 14,983 |

|

| |

| Population Characteristics | |

|

| |

| % African Americans: | |

| 100%a | 25 (66%) |

| 80-99% | 13 (34%) |

|

| |

| Specifically targeting youth: | |

| Yes | 9 (24%) |

| No | 29 (76%) |

|

| |

| Specifically targeting drug users: |

|

| Yes | 11 (29%) |

| No | 27 (71%) |

|

| |

| Gender: | |

| Male only | 8 (21%) |

| Female only | 15 (39%) |

| Mixed | 15 (39%) |

|

| |

| Demographics: | |

| Age (Range) ( k = 15) | 9 – 66 |

| Income (range) (k = 11) | <$500 - <$20,000 |

| Education (median) | < high school |

|

| |

| Intervention setting | |

| Clinic settings | 18 (47%) |

| Community settings | 11(29%) |

| Educational/Research | 9 (24%) |

|

| |

| Intervention delivery | |

| Small groups | 27 (70%) |

| Individually | 9 (24%) |

| Individual and small groups | 2 (5%) |

|

| |

| Sessions | |

| # of sessions (range) | 1-16 |

| time of delivery (range) | 14-960 minutes |

| delivery span (range) | 1-270 days |

Include trials that consisted of 100% African Americans or trials that targeted or focused on African Americans and provided stratified data for African Americans

With few exceptions, the trials were based-on behavioral change theories (e.g., Social Cognitive Theory, Information-Motivation Behavior Model), and two-thirds were culturally tailored specifically for African Americans (e.g., ethnically matched facilitators, ethnographic research). Most trials contained multiple intervention components aimed at reducing sexual risk. Skills training components were the most common and took specific forms including correct use of male condoms or negotiating safer sex. Most interventions were delivered in small groups, and most trials were comprised of 2-5 sessions over 2-30 days.

Methodological quality of the trials

Only a small portion of the trials reported information pertaining to sequence generation (37%), allocation concealment (26%), and blinding (34%). Mean participation rate and retention rate at the first follow-up was 70% among 17 trials reporting participation rates and 73% among 31 trials reporting retention rates. In the majority of the trials differential retention rates among intervention and comparison groups were less than 10%, but two reported greater than 20% differential retention rates. The median sample size at baseline enrollment across all trials was 211. Only one third of the trials reported that power analysis was conducted to estimate the sample size. All trials used intent-to-treat analysis.

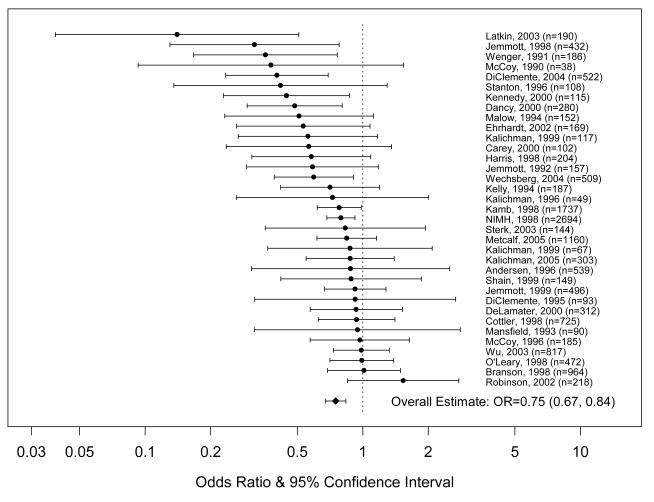

Effect sizes for self-reported HIV risk sexual behavior

Thirty-five RCTs provided data on self-reported HIV risk behavior from 14,682 participants. The aggregated effect size was significant (OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.67, 0.84), indicating that the intervention groups had 25% reduction in odds of reporting unprotected sex behavior compared to comparison groups, at an average of 3 months post intervention. Examination of the forest plot (Figure 2) and the homogeneity test (Q35 = 50.63, p < 0.05) indicated that there was heterogeneity between trials. However, sensitivity tests did not reveal any individual trial that exerted influence on the overall heterogeneity. Additional sensitivity tests, using all available data, showed significant intervention effects were observed in studies with a follow-up of less than 3 months (OR = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.51, 0.87, N = 8), in studies with a follow-up of approximately 3 months (OR = 0.78, 95% CI= 0.69, 0.89, N = 18), and in studies with approximately a 6-month follow-up (OF = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.61, 0.90, N = 18). Studies with a follow-up of longer than six months had marginally significant effect on risk reduction (OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.62, 1.05, N = 12). Significant intervention effects were observed for unprotected sex (OR = 0.79, 95% CI = 0.71, 0.88, N = 22) and condom use (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.52, 0.75, N = 22).

Figure 2.

Study Specific and Overall Effect Size Estimates for Unprotected Sex (N=35)

We conducted stratified analyses to further examine heterogeneity among trials. Significantly greater efficacy was found among trials that addressed social norms toward safer sex compared to trials that did not address social norms, (QB = 13.02, p < .001). Similarly, significantly greater efficacy was found in trials that utilized peer education, compared to trials that did not have peer education (QB = 3.83, p = .05). A methodological feature associated with differential efficacy was type of comparison group. Trials where comparison groups also received some HIV intervention components were less efficacious than trials where comparison groups did not receive any HIV-related intervention (QB = 4.51, p <.05).

As seen in Table 3, a significant intervention effect was observed in trials regardless of the participant characteristics, methodological quality of trials, or intervention features (i.e., intervention setting, self-efficacy). There were several instances where the aggregated intervention effect size was significant in trials with a specific characteristic (e.g., culturally tailored), while the aggregated effect size was not significant in trials without that characteristic. We explored those qualitative differences as they may provide clues about potentially important factors associated with efficacy (Table 3). Intervention groups were significantly less likely than comparison groups to report unprotected sex in trials that were culturally tailored for African Americans; were delivered in a minority community, were based on behavioral change theory; provided skills training on correct use of condoms and negotiation of safer sex; had more than 1 intervention session, had sessions that lasted more than 1 day, and had more than 160 minutes of cumulative intervention time.

Table 3.

Stratified Analysis for Intervention Components for RCTs with African-American Heterosexuals.

| OR (95% CI, no. of trials) Unprotected Sex |

OR (95% CI, no. of trials) Incident STD |

|

|---|---|---|

| Overall: | 0.75 (0.68, 0.84, k = 35) | 0.86 (0.71, 1.03, k = 10) |

|

| ||

| Population Characteristics |

||

|

| ||

| % African American | ||

| 100% a | 0.73 (0.66, 0.82, k = 23) | 0.83 (0.65, 1.04, k = 7) |

| 80-99% | 0.80 (0.63, 1.03, k = 12) | 0.95 (0.70, 1.30, k = 3) |

|

| ||

| Specifically targeting youth: |

||

| Yes | 0.67 (0.51, 0.89, k = 9) | --- |

| No | 0.77 (0.69, 0.86, k = 26) | 0.87, (0.73, 1.04, k = 9) |

|

| ||

| Specifically targeting drug users: |

||

| Yes | 0.67 (0.52, 0.87, k = 10) | --- |

| No | 0.77 (0.68, 0.87, k = 25) | 0.86 (0.71, 1.03, k = 10) |

|

| ||

| Gender: | ||

| Male only | 0.77 (0.59, 1.00, k = 6) | 0.99, (0.58, 1.71, k = 2) |

| Female only | 0.70 (0.59, 0.83, k = 14) | 0.67 (0.44, 1.01, k = 5) |

| Mixed | 0.78 (0.66, 0.92, k = 15) | 0.96, (0.79, 1.16, k = 3) |

|

| ||

| Design and Assessment: | ||

|

| ||

| Reporting of RCT (reporting some combination of RCT components, retention rates, or power) |

||

| Reported 0 | 0.90 (0.70, 1.16, k = 5) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.34, k = 2) |

| Reported 1-3 | 0.75 (0.63, 0.89, k = 17) | ---- |

| Reported 4-7 | 0.70 (0.58, 0.84, k = 13) | 0.85,(0.67, 1.09, k = 7) |

|

| ||

| Comparison group received HIV-related intervention component |

||

| Yes | 0.83 (0.75, 0.93, k = 24) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03, k=9) |

| No | 0.60 (0.48, 0.72, k =11) | -- |

|

| ||

| Participation rate | ||

| < 70% | 0.73 (0.56, 0.96, k = 7) | 0.83 (0.62, 1.09, k = 3) |

| => 70% | 0.71 (0.61, 0.83, k = 13) | 0.87 (0.66, 1.14, k = 7) |

|

| ||

| Retention rate | ||

| < 70% | 0.82 (0.68, 0.99, k = 9) | 0.98, (0.78, 1.24, k = 4) |

| 70% - 79% | 0.77 (0,65, 0.92, k = 14) | 0.74 (0.52, 1.06, k = 3) |

| > 80% | 0.65 (0.52, 0.82, k = 12) | 0.64 (0.33, 1.26, k = 3) |

|

| ||

| Intervention characteristics: |

||

|

| ||

| Culturally tailored | ||

| Yes | 0.73 (0.66, 0.82, k = 23) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.18, k = 5) |

| No | 0.80 (0.63, 1.03, k = 12) | 0.85 (0.67, 1.10, k = 5) |

|

| ||

| Cultural Tailoring Aspects: |

||

| Ethnically matched deliverer |

||

| Yes | 0.69 (0.55, 0.86, k = 13) | 0.63 (0.38, 1.04, k = 3) |

| No | 0.79 (0.71, 0.89, k = 22) | 0.92 (0.74, 1.14, k = 7) |

| Delivered intervention in minority community |

||

| Yes | 0.75 (0.67, 0.84, k = 30) | 0.86 (0.69, 1.07, k = 8) |

| No | 0.72 (0.52, 1.01, k = 5) | 0.80 (0.46, 1.37, k = 2) |

| Reported ethnographic research |

||

| Yes | 0.75 (0.64, 0.88, k=18) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.18, k=5) |

| No | 0.74 (0.63, 0.87, k=17) | 0.85 (0.67, 1.10, k=5) |

|

| ||

| Theory: | ||

| Reported | 0.76 (0.68, 0.84, k = 31) | 0.78 (0.66, 0.94, k = 8) |

| Not Reported | 0.64 (0.36, 1.14, k = 4) | 1.24 (0.91, 1.68, k = 2) |

|

| ||

| Setting: | ||

| Community | 0.67 (0.47, 0.95, k = 8) | 1.37 (0.85, 2.19, k=1) |

| Clinics | 0.76 (0.66, 0.87, k = 16) | 0.84 (0.70, 1.01, k = 8) |

| Education/Research | 0.80 (0.67, 0.96, k = 11) | 0.57 (0.29, 1.13, k=1) |

|

| ||

| Unit of delivery | ||

| Individual | 0.81 (0.70, 0.94, k = 8) | 0.85 (0.58, 1.24, k = 4) |

| Group | 0.72 (0.62, 0.83, k = 25) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08, k = 6) |

| Individual and group |

0.63 (0.43, 0.93, k = 2) | ---- |

|

| ||

| Type of delivererb | ||

| Health care provider | 0.68 (0.51, 0.90, k = 6) | ---- |

| Peer | 0.59 (0.40, 0.89, k = 8) | ---- |

| Research staff | 0.78, (0.69, 0.89, k = 17) | 0.76 (0.55, 1.04, k = 4) |

| Counselor | 0.84 (0.71, 0.99, k = 5) | 0.91, (0.71, 1.17, k = 6) |

|

| ||

| Intervention components: |

||

| Skill Training | ||

| No condom skill or interpersonal skill |

0.79 (0.60, 1.06, k = 5) | 0.92 (0.74, 1.14, k = 3) |

| Have either condom or interpersonal skill |

0.73 (0.58, 0.92, k = 11) | 1.00 (0.77, 1,29, k = 3) |

| Have both condom and interpersonal skill |

0.74 (0.64, 0.86, k = 19) | 0.68 (0.47, 0.98, k = 4) |

| Attitude toward condom use |

||

| Yes | 0.71 (0.58, 0.87, k = 24) | 0.86 (0.66, 1.13, k = 4) |

| No | 0.77 (0.68, 0.88, k = 24) | 0.85 (0.63, 1.13, k = 6) |

| Self-efficacy | ||

| Yes | 0.74 (0.64, 0.87, k = 15) | 0.76 (0.56, 1.02, k = 5) |

| No | 0.74 (0.64, 0.88, k = 20) | 0.95 (0.74, 1.20, k = 5) |

| Motivation for protective behavior |

||

| Yes | 0.80 (0.70, 0.90, k = 8) | 0.92 (0.70, 1.20, k = 5) |

| No | 0.72 (0.62, 0.83, k = 26) | 0.81 (0.62, 1.06, k = 5) |

| Social norms | ||

| Yes | 0.51 (0.40, 0.66, k = 8) | 0.57 (0.08, 4.28, k = 2) |

| No | 0.82 (0.74, 0.90, k = 27) | 0.83 (0.71, 0.98, k = 8) |

| Peer education | ||

| Yes | 0.59 (0.40, 0.89, k = 8) | 0.17 (0.03, 0.94, k = 1) |

| No | 0.81 (0.74, 0.87, k = 27) | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03, k = 9) |

|

| ||

| Intervention # sessions | ||

| 1 session | 0.87 (0.76, 1.01, k = 10) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.12, k = 4) |

| 2-5 sessions | 0.76 (0.65, 0.89, k = 16) | 0.82 (0.61, 1.11, k = 6) |

| > 5 sessions | 0.59 (0.43, 0.80, k = 8) | --- |

|

| ||

| Intervention time span | ||

| 1 day | 0.87 (0.74, 1.03, k = 8) | 0.85 (0.60, 1.22, k = 3) |

| 2-30 days | 0.67 (0.55, 0.81, k = 14) | 0.78 (0.53, 1.16, k = 5) |

| > 30 days | 0.77 (0.63, 0.94, k = 8) | 0.96 (0.77, 1.19, k = 2) |

|

| ||

| Intervention duration | ||

| <160 minutes | 0.87 (0.73, 1.03, k = 7) | 0.96 (0.76, 1.22, k = 5) |

| 160-400 minutes | 0.78 (0.67, 0.90, k = 12) | 0.76 (0.53, 1.10, k = 2) |

| >400 minutes | 0.62 (0.49, 0.79, k = 12) | 0.64 (0.33, 1.26, k = 3) |

Include trials that consisted of 100% African Americans or trials that targeted or focused on African Americans and provided stratified data for African Americans

Not mutually exclusive

Effect sizes for incident STDs

Data on incident STDs were available from 10 RCTs that included 10,944 participants. The aggregated effect size was marginally significant (OR = 0.88, 95% CI = 0.72, 1.07), indicating that the intervention groups had 12% reduction in the odds of incident STD compared to comparison groups. The homogeneity test (Q10 = 18.61, p < 0.03) indicated heterogeneity between trials. Sensitivity tests indicated that excluding one trial [54] made the intervention effect significant (OR = 0.82, 95% CI=0.69, 0.98, N = 9). However, none of the studies significantly reduced the overall heterogeneity. Additional sensitivity tests showed marginally significant intervention effects were observed in studies with follow-ups longer than 12 months (OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.59, 1.00, N = 7), but the intervention effect was not significant in trials with follow-ups less than 12 months (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.82, 1.21, k = 3).

QB tests did not yield any meaningful group differences, primarily due to the small number of trials. We explored the qualitative differences between trials where those reporting a characteristic demonstrated a significant intervention effect compared to trials not reporting that characteristic and not demonstrating a significant effect. This pattern was found in four variables: based on behavioral change theory; providing trainings on correct use of condom and negotiation of safer sex; addressing social norms about safer sex; and peer education.

Examination for publication bias

Based on the linear regression test, we found evidence of publication bias for 35 trials that provide unprotected sex/condom use outcomes (t = −2.614, p = 0.013). The funnel plot was asymmetrical, suggesting that fewer studies with negative interventions effects and large variance were identified in this review (Figure not shown). There is no evidence of publication bias for the STD outcomes (t = −0.631, p = 0.546).

DISCUSSION

Our review shows that behavioral interventions can significantly and positively influence sexual risk behaviors among African-American heterosexuals. The significant reduction in unprotected sex remained up to six months following the completion of interventions. Our overall finding (OR = 0.75) is comparable to the findings of other meta-analyses evaluating HIV prevention interventions for heterosexual adults [8] and adolescents [70]. We also found a marginally significant effect on incident STDs (OR = 0.88), especially at follow-ups greater than 12 months post intervention. However, the effect became significant when eliminating the trial of the lowest methodological quality [54]. This evidence suggests that behavioral interventions can be efficacious not only in changing unprotected sex behaviors but may also reduce incident STDs in African-American heterosexuals.

We identified a number of intervention components associated with risk reduction. Greater efficacy was found for interventions that utilized peer education and aimed to influence social norms about safer sex. Our findings suggest that the influence of peers and the perception of the norms of one’s peers should be considered in developing effective interventions for heterosexual African Americans.

When exploring differences between interventions with a particular characteristic to those without that characteristic for the sex outcomes, we identified several patterns that may provide additional information for prevention efforts. Consistent with previous qualitative reviews [16, 18, 19], cultural tailoring appears to be an important component for reducing sex risk behaviors among African-American heterosexuals. Intriguingly, we did not find any differential efficacy for the particular components of culturally tailored interventions. It is plausible that our inclusion criteria, which stipulated that trials be comprised of at least 80% African-American participants, reduced the variance necessary to detect an effect. More research is needed to assess which specific cultural tailoring components are the active ingredients underlying behavior change.

Additional intervention components that are likely to contribute to behavior change are skills training and negotiation. Utilizing skills training is typical of interventions guided by social cognitive theories, which represent a majority of the interventions in this analysis. There is also evidence of a dose response relationship regarding number of sessions, time span, and duration of interventions. The independent contributions of these intervention characteristics cannot be disentangled within these data as the majority of the interventions utilized multiple components and sessions over multiple days. However, the overall findings suggest that behavioral interventions are more likely to achieve success if they incorporate skills training and provide opportunities for practicing skills. In addition, future interventions may benefit from utilizing multiple sessions over multiple days, lasting several hours in total length.

The findings of our review must be viewed within the context of the limitations of the available evidence. Interventions we reviewed primarily addressed heterosexual transmission of HIV although some portions of men who also engaged in same-sex behavior but did not identify themselves as homosexual may have participated. Recent studies have indicated that non-gay identified MSM are more likely to have a female partner and to have had unprotected vaginal sex [71]. Additionally the majority of the trials were unblinded and relied on self-reported sexual behavior, which may result in social desirability bias [72]. However, several factors reduce the likelihood of this being an undue influence. First, the majority of interventions made efforts to reduce this effect by techniques such as ensuring confidentiality. Second, our findings with behavioral outcomes are similar to our outcomes from STDs, which corroborates the self-reported sex behavior findings. Future research should include biological assessment as well as self-reported sexual behavior as this would increase our ability to evaluate the impact of interventions. Finally, all the trials had a comparison group and the assignment method was randomization, which reduced the likelihood that individual characteristics influenced the intervention effect. Our findings were also limited in that the majority of interventions (23/26) did not distinguish between primary and secondary partners in their analysis. Given that condom use has been found to differ between these types of partners [73], we recommend that future studies examine these partner-level differences both when assessing and reporting episodes of unprotected sex and condom use. Our meta-analysis was also limited by the fact that we only included individual-level and group-level interventions. There were only a few randomized community-level and structural-level interventions available in the literature [e.g., 74, 75, 76]. However, given that many risk factors associated with HIV risk-taking in African-American heterosexuals are structural (e.g., poverty, access to care) future research should evaluate community-level and structural level interventions when more RCTs become available.

Despite these limitations, our findings also pointed out several implications for future research. It is encouraging to see several of the intervention studies [48, 49] in our review were conducted with heterosexual African-American men, an understudied group [8, 77]. Although studies targeting African-American adolescents were well represented in this review, few of these studies focused on younger adolescents. It is possible that the approach for HIV sex risk reduction among younger African-American adolescents may be different from older adolescents (e.g., interventions may emphasize delay of sexual initiation). We also did not identify any trials that examined prison populations, which have a high HIV prevalence compared to the general population [78].

While our findings offer some evidence for factors associated with intervention efficacy in reducing HIV-risk sex behavior in African-American heterosexuals, to make a real impact on the HIV/AIDS epidemic, it is important to translate and disseminate evidence-based research. Some progress has been made in translating scientific-based knowledge into user-friendly intervention packages for dissemination through two CDC projects - Replicating Effective Programs (REP) and Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions (DEBI). Several interventions for African-American heterosexuals have been packaged or are in the process of packaging (see PRS efficacy website: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/prs/about.htm; [79]). However, translating research findings into effective interventions in real world settings remains challenging. Although additional research needs to be conducted with regard to this translation, and some limitations to our methodology have been discussed, our findings for both behavioral and biological outcomes suggest that the behavioral strategies utilized in the included interventions can reduce the frequency of HIV risk behaviors in African-American heterosexuals. Thus, we suggest that the following efficacious intervention components identified in this review should be incorporated into the development of future interventions and further evaluated for effectiveness: (1) cultural tailoring, (2) social norms in promoting safer sex behavior, (3) peer education, (4) skills training on correct use of condoms and communication skills needed for negotiating safer sex, and (5) multiple sessions and opportunities to practice skills. Future interventions that are aimed toward African-American heterosexual participants should take the unique needs of the community into account.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Detection system for STD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

L.A. Darbes, G.E. Kennedy and G.W. Rutherford supported in part through grants from the Office of AIDS, California Department of Health Services, and from the Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and L.A. Darbes from NIH grant K08 MH 072380. The work of N. Crepaz and C.M. Lyles was supported by the Prevention Research Branch, Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and was not funded by any other organization.

All authors contributed to review concept and synthesis method. L.A. Darbes led the writing of the introduction and discussion, scope screened studies, contacted authors for additional information, and abstracted qualitative data. N. Crepaz led the writing of methods and results, abstracted qualitative and quantitative data, and conducted meta-analysis. C.M. Lyles abstracted qualitative and quantitative data, helped with quantitative analysis, and provided critical review of the manuscript. G.E. Kennedy helped out screening studies, abstracted qualitative data, and provided critical review of the manuscript. G.W. Rutherford provided critical review of the manuscript.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Other members of the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team who contributed to this review are (listed alphabetically): Julia Deluca, Jeffrey H. Herbst, Angela K. Horn, Linda Kay, Elizabeth Jacobs, Mary Mullins, Warren Passin, Sima Rama, Sekhar Thadiparthi, and Lev Zohrabyan

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report, 2004. Vol. 16. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2005. Also available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasrlink.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Racial ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS – 33 states, 2001-2004. Morbidity and Mortality weekly Report (MMWR) 2006;55:121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbst JH, Sherba RT, Crepaz N, DeLuca JB, Zohrabyah L, Stall RD, Lyles CM, for the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team A meta-analytic review of HIV behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk behavior of men who have sex with men. JAIDS. 2005;39:228–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Ramirez G, Semann S, Norman LR, Sogolow E, et al. HIV prevention research for men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Jul 1;30(Suppl 1):S118–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson WD, Holtgrave DR, McClellan WM, Flanders WD, Hill AN, Goodman M. HIV intervention research for men who have sex with men: a 7-year update. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(6):568–589. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.6.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: social and contextual factors, meta-analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychol Bull. 2002 Nov;128(6):851–85. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mize SJ, Robinson BE, Bockting WO, Scheltema KE. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of HIV prevention interventions for women. AIDS Care. 2002 Apr;14(2):163–80. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neumann MS, Johnson WD, Semaan S, Flores SA, Peersman G, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Review and meta-analysis of HIV prevention intervention research for heterosexual adult populations in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Jul 1;30(Suppl 1):S106–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semaan S, Des Jarlais DC, Sogolow E, Johnson WD, Hedges LV, Ramirez G, Flores SA, Norman L, Sweat MD, Needle R. A meta-analysis of the effect of HIV prevention interventions on sex behavior of drug users in the U.S. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Jul 1;30(Suppl 1):S73–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Copenhaver MM, Johnson BT, Lee IC, Harman JJ, Carey MP, SHARP Research Team Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: A meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Treatment. 2006;31(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985-2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003 Apr;157(4):381–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim N, Stanton B, Li X, Dickersin K, Galbraith J. Effectiveness of the 40 adolescent AIDS-risk reduction interventions: A quantitative review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;20:204–215. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV, for the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward DJ, Rowe B, Pattison H. Reducing the risk of sexually transmitted infections in genitourinary medicine clinic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2005;81:386–389. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.013714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crepaz N, Horn AK, Rama SM, Griffin T, Deluca JB, Mullins MM, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk sex behaviors and incident sexually transmitted disease in Black and Hispanic sexually transmitted disease clinic patients in the United States: A meta-analytic review. Sexually Transmitted Disease. 2007;34(6):319–332. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000240342.12960.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beatty LA, Wheeler D, Gaiter J. HIV prevention research for African Americans: Current and future directions. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;31(1):40–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNair LD, Prather CM. African American women and AIDS: Factors influencing risk and reaction to HIV disease. Journal of Black Psychology. 2004;30(1):106–123. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams PB. HIV/AIDS case profile of African Americans. Guidelines for ethnic-specific health promotion, education, and risk reduction activities for African Americans. Family and Community Health. 2003;26(4):289–306. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darbes LA, Kennedy GE, Peersman G, Zohrabyan L, Rutherford G. A systematic review of behavioral HIV prevention interventions for African Americans in the U.S. Government Report. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2002. http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite?page=kb-00&doc=kb-07-04-09. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott KD, Gilliam A, Braxton K. Culturally competent HIV prevention strategies for women of color in the United States. Health Care for Women International. 2005;26:17–45. doi: 10.1080/07399330590885795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson BDB, Miller RL. Examining strategies for culturally grounded HIV prevention: A review. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15(2):184–202. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.184.23838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. The Cochrane Library. Issue 4. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chicester, U.K.: 2006. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6. (updated September 2006) 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Kay LS, for the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team Evidence based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of CDC’s HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(Suppl A):21–31. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deluca JB, Mullins MM, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Kay L, Thadiparthi S, the HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Team A framework for developing a systematic search strategy for HIV/AIDS behavioral intervention research literature. Unpublished manuscript.

- 25.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper H, Hedges LV. The handbook of research synthesis. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed and random effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Meth. 1998;3:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a sample, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersen MD, Hockman EM, Smereck GAD. Effect of a nursing outreach intervention to drug users in Detroit, Michigan. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26(3):619–634. * [Google Scholar]

- 33.Branson BM, Peterman TA, Cannon RO, Ransom R, Zaidi AA. Group counseling to prevent sexually transmitted disease and HIV: A randomized control trial. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1998 Nov;:553–560. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199811000-00011. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carey MP, Braaten LS, Maisto SA, Gleason JR, Forsyth AD, Durant LE, Jaworski BC. Using information, motivational enhancement and skills training to reduce the risk of HIV infection for low-income urban women: a second randomized clinical trial. Health Psychology. 2000;19(1):3–11. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.3. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cottler LB, Compton WM, Abdallah AB, Cunningham-Williams R, Abram F, Fichtenbaum C, Dotson W. Peer-delivered interventions reduce HIV risk behaviors among out-of-treatment drug abusers. Public Health Reports. 1998;113(Suppl 1):31–41. * [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dancy BL, Marcantonio R, Norr K. The long-term effectiveness of an HIV prevention intervention for low-income African American women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(2):113–125. * [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.DeLamater J, Wagstaff DA, Havens KK. The impact of a culturally appropriate STD/AIDS education intervention on black male adolescents’ sexual and condom use behavior. Health Educ Behav. 2000 Aug;27(4):454–70. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700408. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. A randomized controlled trial of an HIV sexual risk-reduction intervention for young African-American women. JAMA. 1995;274(16):1271–1276. * [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Lang DL, Davies SL, Hook EW, Oh MK, Crosby RA, Hertzberg VS, Gordon AB, Hardin JW, Parker S, Robillard A. Efficacy of an HIV prevention intervention for African American adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(2):171–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.171. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehrhardt AA, Exner TM, Hoffman S, Silberman I, Leu CS, Miller S, Levin B. A gender-specific HIV/STD risk reduction intervention for women in a health care setting: short- and long-term results of a randomized clinical trial. AIDS Care. 2002;14(2):147–161. doi: 10.1080/09540120220104677. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gollub EL, French P, Loundou A, Latka M, Rogers C, Stein Z. A randomized trial of hierarchical counseling in a short, clinic-based intervention to reduce risk of sexually transmitted diseases in women. AIDS. 2000;14(9):1249–1255. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006160-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harris RM, Bausell RG, Scott DE, Hetherington SE, Kavanagh KH. An intervention for changing high-risk HIV behaviors of African-American drug-dependent women. Research in Nursing and Health. 1998;21:239–250. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199806)21:3<239::aid-nur7>3.0.co;2-i. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Reductions in HIV risk-associated sexual behaviors among Black male adolescents: Effects of an AIDS prevention intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82(3):372–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.372. * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African-American adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT, McCaffree K. Reducing HIV risk-associated sexual behavior among African American adolescents: Testing the generality of intervention effects. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(2):161–187. doi: 10.1007/BF02503158. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Experimental component analysis of a behavioral HIV-AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(4):687–693. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.687. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalichman SC, Cherry C. Male polyurethane condoms do not enhance brief HIV-STD risk reduction interventions for heterosexually active men: results from a randomized test of concept. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 1999a;10:548–553. * [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Browne-Sperling F. Effectiveness of a video-based motivational skills-building HIV risk-reduction intervention for inner-city African American men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999b;67(6):959–966. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.959. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalichman SC, Cain D, Weinhardt L, Benotsch E, Presser K, Zweben A, Bjodstrup B, Swain GR. Experimental components analysis of brief theory-based HIV/AIDS risk-reduction counseling for sexually transmitted infection patients. Health Psychology. 2005;24(2):198–208. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.198. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr., Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, Zenilman J, Hoxworth T, Malotte K, Iatesta M, Kent C, Lentz A, Graziano S, Byers RH, Peterman TA, for the Project RESPECT Study Group JAMA. 1998;280(13):1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Washington CD, Wilson TS, Koob JJ, Davis DR, Ledezma G, Davantes B. The effects of HIV/AIDS intervention groups for high-risk women in urban clinics. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(12):1918–1922. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.1918. * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kennedy MG, Mizuno Y, Hoffman R, Baume C, Strand J. The effect of tailoring a model HIV prevention program for local adolescent target audiences. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(3):225–238. * [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Latkin CA, Sherman S, Knowlton A. HIV prevention among drug users: Outcome of a network-oriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychology. 2003;22(4):332–339. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maher JE, Peterman TA, Osewe PL, Odusanya S, Scerba JR. Evaluation of a community-based organizations’ intervention to reduce the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Southern Medical Journal. 2003;96(3):248–253. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000054605.31081.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malow RM, West JA, Corrigan SA, Pena JM, Cunningham SC. Outcome of psychoeducation for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1994;6(2):113–125. * [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mansfield CJ, Conry ME, Emans SJ, Woods ER. A pilot study of AIDS education and counseling of high-risk adolescents in an office setting. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1993;14:115–119. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90095-7. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCoy CB, Weatherby NL, Metsch LR, McCoy HV, Rivers JE, Correa R. Effectiveness of HIV interventions among crack users. Drugs and Society. 1996;9(1/2):137–154. * [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCoy CB, Khoury EL. The effectiveness of a risk reduction program in Belle Glade, Florida at the six-month follow-up assessment. Paper presented at the Second Annual NADR National Meeting; 1990. * [Google Scholar]

- 59.Metcalf CA, Malotte K, Douglas JM, Paul SM, Dillon BA, Cross H, Brookes LC, Deaugustine N, Lindsey CA, Byers RH, Peterman TA, for the Respect-2 Study group Efficacy of a booster counseling session 6 months after HIV testing and counseling: A randomized controlled trial (RESPECT-2) Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(2):123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151420.92624.c0. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.NIMH Multisite HIV Prevention Trial Group The NIMH multisite HIV prevention trial: Reducing HIV sexual risk behavior. Science. 1998;280:1889–1894. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1889. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Donnell CR, O’Donnell L, San Doval A, Duran R, Labes K. Reductions in STD infections subsequent to an STD clinic visit: Using video-based patient education to supplement provider interactions. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1998;25:161–168. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199803000-00010. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O’Leary A, Ambrose TK, Raffaelli M, Maibach E, Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, Labouvie E, Celentano D. Effects of an AIDS risk reduction project on sexual risk behavior of low-income STD patients. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1998;10:483–492. * [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson BB, Uhl G, Miner M, Bockting WO, Scheltema KE, Rosser BR, Westover B. Evaluation of a sexual health approach to prevent HIV among low income, urban, primarily African American women: results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002 Jun;14(3 Suppl A):81–96. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.4.81.23876. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shain RN, Piper JM, Newton ER, Perdue ST, Ramos R, Champion JD, Guerra FA. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:93–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400203. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stanton BF, Li X, Ricardo I, Galbraith J, Feigelman S, Kaljee L. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of an AIDS prevention program for low-income African-American youths. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1996;150:363–372. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290029004. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sterk CE, Theall KP, Elifson KW, Kidder D. HIV risk reduction among African-American women who inject drugs: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS and Behavior. 2003;7(1):73–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1022565524508. * [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wechsberg WM, Lam WKK, Zule WA, Bobashev G. Efficacy of a woman-focused intervention to reduce HIV risk and increase self-sufficiency among African American crack abusers. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(7):1165–1173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1165. * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wenger NS, Linn LS, Epstein M, Shapiro MF. Reduction of high-risk sexual behavior among heterosexuals undergoing HIV antibody testing: a randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:1580–1581. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.12.1580. * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu Y, Stanton BF, Galbraith J, Kaljee L, Cottrell L, Li X, Harris CV, D’Alessandri D, Burns JM. Sustaining and broadening intervention impact: A longitudinal randomized trial of 3 adolescent risk reduction approaches. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):32–38. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mullen PD, Ramirez G, Strouse D, Hedges LV, Sogolow E. Meta-analysis of the effects of behavioral HIV prevention interventions on the sexual risk behavior of sexually experienced adolescents in controlled studies in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002 Jul 1;30(Suppl 1):S94–S105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]