Abstract

BACKGROUND

Chronic pain is common in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and often attributed to inflammation. However, many IBD patients without evidence of active disease continue to experience pain. This study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of pain in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients and examine the role of inflammation and psychiatric comorbidities in UC patients with pain.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of adult UC patients seen at a tertiary referral IBD center. Age, gender, disease duration and extent, abdominal pain rating, quality of life, physician global assessment (PGA), endoscopic and histologic rating of disease severity, C reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were abstracted.

RESULTS

1268 patients were identified using billing codes for colitis. 502 (48.2% women) met all inclusion criteria. 262 (52.2%) individuals complained of abdominal pain, with 108 (21.5%) individuals describing more frequent pain (‘some of the time or more’). Of those with quiescent disease (n=326), 33 (10%) patients complained of more frequent pain. PGA, endoscopic and histologic severity rating, ESR and CRP significantly correlated with pain ratings. The best predictors of pain were PGA, CRP and ESR, female gender and coexisting mood disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

Abdominal pain affects more than 50% of UC patients. While inflammation is important, the skewed gender distribution and correlation with mood disorders highlights parallels with functional bowel disorders and suggest a significant role for central mechanisms. Management strategies should thus go beyond a focus on inflammation and also include interventions that target psychological mechanisms of pain.

Keywords: Ulcerative Colitis (UC), Pain, Affective Spectrum Disorder, Depression, Anxiety, Functional Bowel Disorder, Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Introduction

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) encompasses a set of disorders, including Crohn’s Disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), characterized by chronic relapsing inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of chronic pain in IBD patients. Pain is a presenting symptom in up to 70% of patients experiencing the initial onset or exacerbations of the disease1. Every year, pain and other related symptoms in IBD account for over a billion dollars in health care expenditures and lost work hours2, 3. In addition to the economic burden, pain and/or fear of pain negatively affect quality of life4. The impact may even go beyond morbidity, quality of life and cost, as pain management with narcotics carries a higher mortality risk5–7.

The inflammation associated with IBD is often considered to be the primary driver of abdominal pain, as inflammatory cytokines and mediators enhance the excitability of sensory nerves that convey information about the gut to the brain. While clinical and experimental data support this conceptual framework, inflammation by itself is not sufficient to explain all pain experience in IBD. Previous estimates suggest that up to one third of individuals with UC and more than half of the individuals with CD continue to experience persistent symptoms, including chronic pain, even though clinical and endoscopic findings demonstrate that their disease is in remission8–11. These observations have blurred the lines between so-called organic and functional diseases, leading several investigators to conclude that functional bowel disorders (such as IBS) may coexist with IBD or even be triggered by the underlying inflammation 12. Interestingly, altered coping styles and affective spectrum disorders contribute to ongoing symptoms in patients with quiescent IBD, showing another important parallel with IBS13–17. A recent study focusing on IBS symptoms in quiescent IBD called into question the typical criteria defining a quiescent disease state, as fecal markers suggest that persistent low-grade inflammation may contribute to symptoms18.

Considering the wide range of mechanisms that may contribute to the ongoing gastrointestinal problems in patients, a better understanding of subgroups and risk factors predisposing to development of chronic abdominal pain is essential. Prior investigations focused on CD patients, and, to our knowledge, no previous study has specifically investigated abdominal pain prevalence in ulcerative colitis. We undertook this study to 1) determine the prevalence of abdominal pain in individuals with UC, and 2) examine the potential role of inflammation, psychiatric comorbidities, functional bowel disorders and medication use in UC patients with pain.

Material and Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of all adult UC patients seen at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Digestive Disease Center, Pittsburgh, PA between January 2007 and June 2011. The center provides longitudinal care to over two thousand IBD patients, most of whom are enrolled in ongoing clinical trials and undergo standardized phenotypic characterization of disease extent and activity based on the Montreal classification19. Patient records were retrieved based on billing codes for colitis (International Classification of Diseases 9 codes 556.0–556.3, 556.5, 556.6, 558.8 and 558.9). The first recorded visit during the study period was used as the “index visit.” In order to be included in this study, individuals had to meet the following criteria: 1) age equal or greater than 17 years; 2) established diagnosis of UC (based upon standard clinical criteria incorporating historical, laboratory, endoscopic and histological evaluation); 3) no intestinal surgery (ex: resection, etc.) prior to the index visit, 4) no coexisting condition which could explain abdominal pain, including pregnancy, trauma, malignancy, infection, abscess or non-UC associated inflammatory disorder.

Age, gender, disease duration, disease extent, subjective abdominal pain rating, quality of life, physician global assessment (PGA) of disease severity, endoscopic and histologic rating of disease severity, C reactive protein (CRP, mg/dL) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, mm/hour), comorbidities, and currently prescribed medications were abstracted for the time of the index encounter or the time closest to it. Individual patient responses to the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) and a modified version of the Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index (UCDAI) were routinely collected during each patient visit. PGA was determined at each visit as well. Disease extent was determined by the proximal extent of inflammation within the colon during diagnosis of UC (following the Montreal classification system). Coexistence of IBS was based entirely upon whether or not this diagnosis had been made by the gastroenterologist of record by the time of the index visit. Quality of life scores were derived from individual patient responses to the SIBDQ20. Pain ratings were also based primarily on responses to the SIBDQ, which asks patients to grade pain on a frequency-based Likert scale, with 1 representing pain “all of the time” and 7 representing pain “none of the time”. Thus, the pain rating scale of the SIBDQ is an inverse scale with lower numbers demonstrating more frequent pain. Information about pain severity on the day of the index visit was also collected using responses to a modified ulcerative colitis disease activity index survey, which asked about the severity of abdominal pain with potential responses including 0 (“no abdominal pain”), 1 (“mild”), 2 (“moderate”) and 3 (“severe”). The physician’s global assessment is a summary measure, routinely used in clinical encounters and integrates information derived from historical, examination, laboratory, endoscopic and histological information available to the gastroenterologist of record at the time of the index visit; the verbal descriptors (quiescent, mild, moderate or severe inflammation) were numerically coded in the final data bank 21.

Statistical Analysis

The main outcome variable was pain and was used as a categorical variable and correlated with the presence or absence of active inflammation (based upon information delineated from the clinical record). As a first step, we performed a univariate analysis to determine the correlation between pain ratings and other outcome variables. Pain frequency ratings derived from the SIBDQ were entered as dependent variables and Spearman correlation coefficients were determined. Next, we transformed pain ratings into a dichotomous variable with a pain frequency of at least 4 (“Pain some of the time”) as the cut-off. To determine predictors of pain, this dependent variable was entered into a logistic regression analysis. Variables showing a significant difference in the group comparison or univariate analysis were similarly dichotomized and entered into the model; age and disease duration were divided into distinct cohorts based on threshold levels of 45 years and 10 years, respectively. Several inflammatory indicators were entered into the model based on the prior subgroup or univariate analysis: histological evidence of mild or more severe inflammatory activity was defined as active disease. Elevation of ESR and CRP were separately fed into the analysis. As physician rating and the SIBDQ both include pain data, they were not used to test predictors of pain. Unless indicated specifically, all data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (v. 4.0a; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the unpaired Student t-test or Chi-square test. Comparisons among three or more groups were performed using the one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test. Differences between means at a level of p<0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

Patient Sample

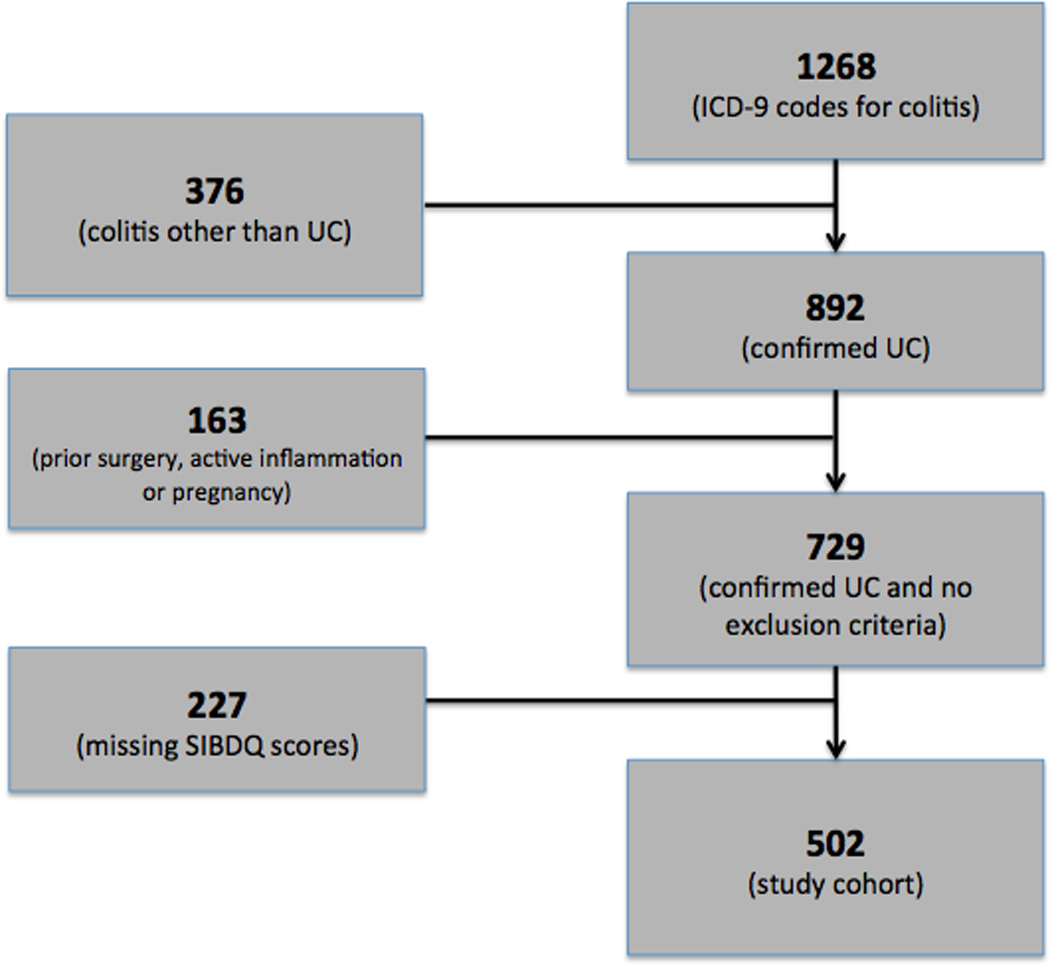

Using billing codes for clinic encounters during the study period, a total of 1268 individuals were found to have ICD-9 codes consistent with colitis or ulcerative colitis. Of these, 892 individuals had a previously confirmed diagnosis of UC. An additional 151 patients with known UC were excluded for having an active infection or inflammatory process other than UC, due to pregnancy at the time of the index visit, or because of prior intestinal surgery. Of the 729 individuals remaining, 502 had provided responses to the SIBDQ questionnaire at the time of their index visit (Figure 1) and were thus included in this study. There were no significant differences between the study sample and the whole UC sample (Table 1). Most of the patients had a long history of UC and more than half suffered from pancolitis (Table 1). Nearly two thirds of the sample (n=322; 64%) had quiescent disease based on the physician global assessment. We performed a univariate analysis to validate the physician global severity assessment abstracted from the chart. As shown in Table 2, there was a significant relationship between this categorical variable and the SIBDQ, endoscopic and histologic findings, inflammatory parameter and pain ratings.

Figure 1.

UC patient selection diagram.

Table 1.

Demographic Data Comparison for All UC Patients and UC Patients with SIBDQ Scores. There were no significant differences in any of these factors between the two groups.

| Variable | All UC patients (n=729) |

UC with SIBDQ scores (n=502) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45.41 ± 0.52 | 44.87 ± 0.73 | NS |

| Gender (f(%)/m(%)) | 350(48.0)/379(52.0) | 242(48.2)/260(51.8) | NS |

| Disease Duration | 10.0 ± 0.31 | 10.17 ± 0.42 | NS |

| CRP | 1.50 ± 0.35 | 1.02 ± 0.22 | NS |

| ESR | 19.70 ± 1.01 | 19.60 ± 1.06 | NS |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of an Affective Spectrum Disorder |

125(17.2%) | 97(19.3%) | NS |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of IBS | 108(14.8%) | 78(15.5%) | NS |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of a Chronic Pain Syndrome |

167(22.9%) | 125(24.9%) | NS |

| Use of Anti-Depressant Med | 108(14.8%) | 78(15.5%) | NS |

| Use of Opiate | 25(3.4%) | 17(3.4%) | NS |

| Use of NSAID | 41(5.6%) | 78(7.6%) | NS |

Table 2.

Correlation matrix showing the relationship between Physician Global Assessment (PGA) and other continuous or categorical endpoints examined

| Age | Disease Duration |

Disease Extent |

SIBDQ Total |

Abd Pain |

Endo Severity |

Histo Severity |

CRP | ESR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGA | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.55** | −0.49** | 0.30** | 0.26** | 0.16** | 0.19** |

| Age | 0.33** | −0.09* | 0.05 | 0.12** | −0.16** | −0.11* | 0.16* | 0.22* | |

| Disease Duration |

0.03 | 0.11* | 0.06 | −0.28** | −0.2** | 0.05 | −0.01 | ||

| Disease Extent |

−0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.03 | |||

| SIBDQ Total Score |

0.74** | −0.23** | −0.19** | −0.15** | −0.24** | ||||

| Presence of Abd Pain |

−0.17** | −0.15** | −0.14* | −0.16** | |||||

| Endoscopi c Severity |

0.83** | 0.22** | 0.22** | ||||||

| Histologic Severity |

0.24** | 0.22** | |||||||

| CRP | 0.57** |

= p<0.05,

= p<0.01.

Pain Prevalence and Associated Factors

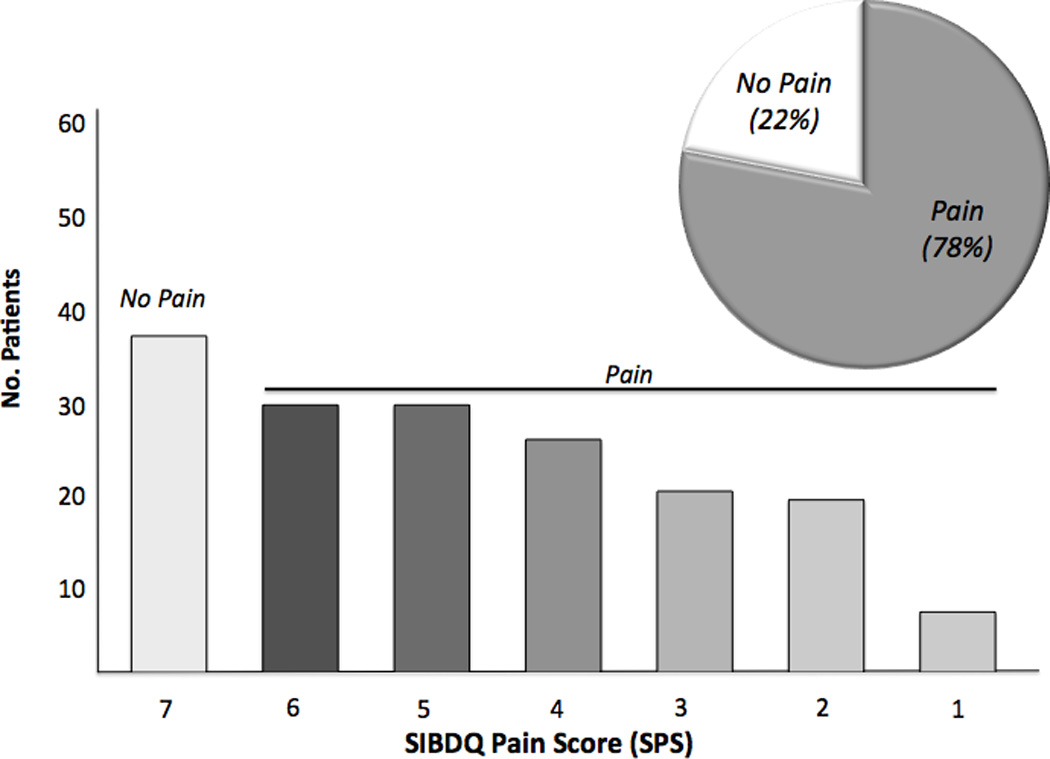

Slightly more than half of the entire group (n=262; 52.3%) endorsed at least some pain over the previous two weeks before or during their index visit, with 108 people (21.5%) reporting a SIBDQ Pain Score (SPS) of at least 4 (Figure 2). Considering the emphasis on frequency rather than severity, we correlated the SPS with the pain severity rating of the Colitis Activity Index, which showed a significant relationship between the two measures (r2=0.59, p<0.0001). Significantly more women (26.4%) than men (16.9%; P<0.05) described their pain as more frequent (i.e. SPS≤4). Of note, 16 (3.2%) patients used opioids at the time of their index visit. Abdominal discomfort was the main reason for opioid use in 6 of these individuals, with the remaining patients receiving pain medications for joint, back, bone or muscle pains (n=7) or chronic pancreatitis (n=1). In the remaining patients, no reason for opioid therapy could be identified. Opioid use was significantly more common in patients rating their pain as frequently or constantly present (8.3%) compared to those with no abdominal pain (1.4%; P<0.01).

Figure 2.

Abdominal Pain Prevalence in UC Patients with SIBDQ Scores. The histogram shows the distribution of pain scores, which are inversely related to pain frequency. The insert defines the fraction of patients with (grey) and without (white) pain.

Predictors of Pain

We compared all UC patients without pain to those who described having a SPS=5–6 or a SPS≤4. One or both of the groups with abdominal pain were found to be younger (SPS=5–6), more frequently female, more likely to have disease limited to the rectum (SPS≤4), more frequently carried concurrent diagnoses of a mood disorder (SPS≤4), IBS and chronic pain disorder (SPS≤4) and had higher mean CRP and ESR values (SPS≤4) (Table 3). We next assessed the univariate relationship between pain ratings and categorical or continuous variables. Younger age, female gender and ESR correlated with a higher pain-related burden.

Table 3.

Clinical Characteristics of UC Patients with and without Abdominal Pain. Key clinical characteristics were compared among the groups of UC individuals without pain, those with a SPS=5–6 and those with a SPS≤4

| Variable | All UC without pain (n=240) |

All UC with SPS = 5 or 6 (n=154) |

All UC with SPS ≤ 4 (n=108) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.4 ± 0.5 | 42.6 ± 1.4* | 43.7 ± 1.7 | <0.05 |

| Gender (f(%)/m(%)) | 91(37.9)/149(62.1) | 87(56.5)/67(43.5) | 64(59.3)/44(40.7) | <0.05# |

| Disease Duration (years) | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 10.3 ± 0.8 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | NS |

| Disease Distribution Proctitis Left-sided Pan-Colitis |

12 (5%) 84 (35%) 134 (60%) |

10 (6.5%) 44 (28.6%) 100 (64.9%) |

15 (13.9%) 27 (25%) 66 (61.1%) |

<0.05# NS NS |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 2.5 ± 0.5* | <0.05 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 16.8 ± 1.2 | 20.5 ± 1.1 | 23.8 ± 1.2* | <0.05 |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of an Affective Spectrum Disorder |

39 (16.5%) | 24 (15.6%) | 35 (32.4%) | <0.01# |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of IBS | 19 (7.9%) | 23 (14.9%) | 26 (24.1%) | <0.001# |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of a Chronic Pain Syndrome |

49 (20.4%) | 39 (29.3%) | 38 (35.1%) | <0.05# |

| Use of Anti-Depressant Medication | 27 (11.3%) | 24 (15.6%) | 28 (25.9%) | <0.01# |

| Use of Opiate | 4 (1.7%) | 4 (2.6%) | 9 (8.3%) | <0.05# |

| Use of NSAID | 24 (10%) | 4 (2.6%) | 10 (9.3%) | <0.05# |

| Use of 5-ASA Therapy | 184 (76.7%) | 123 (79.9%) | 79 (73.1%) | NS |

| Use of Immunomodulator Therapy | 75 (31.3%) | 39 (25.3%) | 30 (27.8%) | NS |

| Use of Biologic Therapy | 48 (20%) | 22 (14.3%) | 16 (14.8%) | NS |

=p<0.05 compared to control (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test);

=chi-square test).

Variables showing significant correlation with pain in the univariate analysis were dichotomized and used in a multiple logistic regression analysis to identify independent predictors of frequent abdominal pain. ESR predicted abdominal pain though, interestingly, neither endoscopic nor histologic grading did so. Consistent with the univariate assessment, female gender increased the odds of pain, as did coexisting mood disorders, chronic pain syndromes and use of opioid medication (Table 4).

Table 4.

Predictors of Pain Ratings. Categorical and continuous variables showing significant correlation with pain in univariate analyses were dichotomized and used in a logistic regression analysis to determine predictors of pain. Results are given as odds ratio with 95% confidence interval. CI – confidence interval; CRP – C reactive protein; ESR – erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 45 years | 0.80 | 0.34–1.90 | 0.61 |

| Male Gender | 0.36 | 0.15–0.87 | 0.02 |

| Normal Histology | 0.85 | 0.32–2.27 | 0.75 |

| Elevated CRP | 1.66 | 0.54–5.12 | 0.38 |

| Elevated ESR | 3.08 | 1.17–8.11 | 0.02 |

| Opioid Use | 8.87 | 1.77–45.58 | <0.01 |

|

Presence of a Mood Disorder |

5.76 | 1.39–23.89 | 0.02 |

| Antidepressant Use | 0.38 | 0.08–1.87 | 0.23 |

|

Presence of a Pain Syndrome |

2.45 | 1.01–5.92 | <0.05 |

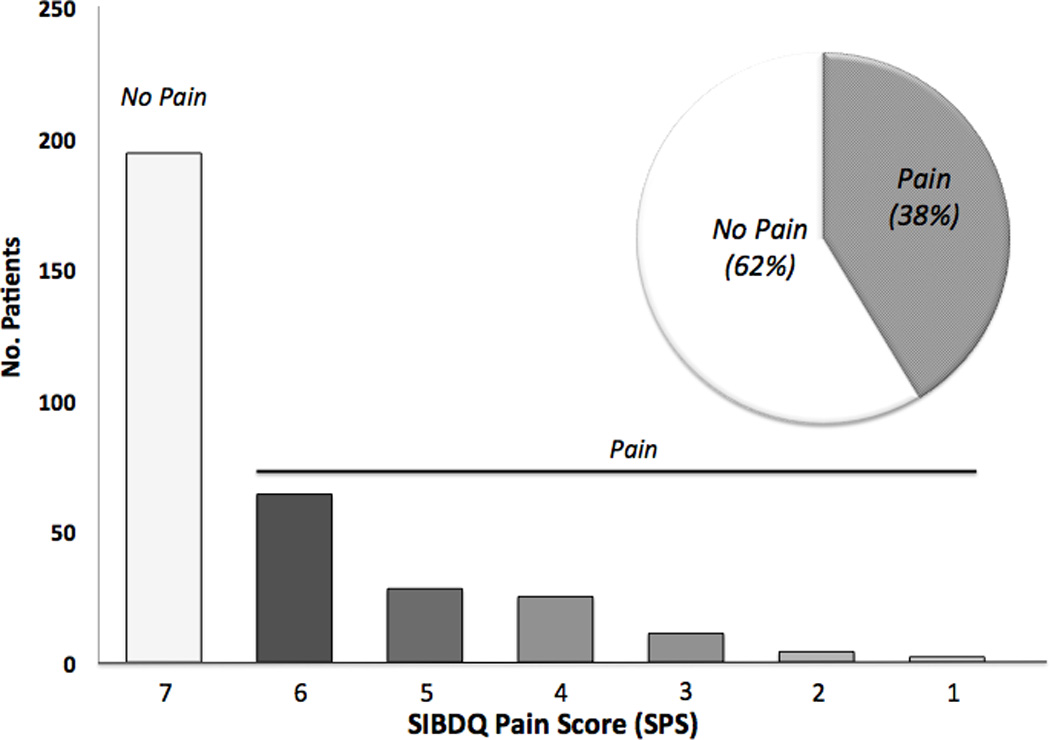

To assess the importance of ongoing inflammation, we dichotomized the sample based on the physician global assessment. In patients with active disease (n=176), 137 individuals (77.8%) described having some degree of abdominal pain while 106 (60.2%) described having frequent to constant abdominal pain (Figure 3a). Of note, 22.1% of individuals deemed to have active UC at the time of the index visit denied any recent abdominal pain. These individuals were on average older (51.7 years of age) and more frequently male (66.7%) compared to those with active UC who reported pain. Of the 322 individuals described as having quiescent disease at the time of the index visit, 125 individuals (38.3%) reported having some pain over the prior two-week period, with 33 patients (10.1%) rating it as frequent to constant (Figure 3b). It was also revealed that individuals with quiescent disease and a SPS≤4 were on average younger, more frequently female, more frequently carried concurrent diagnoses of a mood disorder, IBS and chronic pain disorder and had higher mean ESR values (Table 5). Unlike above, there was no difference in mean CRP values or disease distribution.

Figure 3.

a. Abdominal Pain Prevalence in all Active UC Patients with SIBDQ Scores. The histogram shows the distribution of pain scores, which are inversely related to pain frequency. The insert defines the fraction with (grey) and without (white) pain.

b. Abdominal Pain Prevalence in all Quiescent UC Patients with SIBDQ Scores. The histogram shows the distribution of pain scores, which are inversely related to pain frequency. The insert defines the fraction with (grey) and without (white) pain.

Table 5.

Clinical Characteristics of Quiescent UC Patients with and without Frequent to Constant Abdominal Pain. Patients were defined as having quiescent disease based on the treating physician’s global assessment. Key clinical characteristics were compared among the quiescent groups without pain, those with a SPS=5–6 and those with a SPS≤4

| Variable | Inactive UC without pain (n=201) |

Inactive UC with SPS = 5–6 (n=92) |

Inactive UC with SPS ≤ 4 (n=33) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.9 ± 0.5 | 42.0 ± 1.3 | 40.4 ± 2.0* | <0.05 |

| Gender (f(%)/m(%)) | 78(38.8)/123(61.2) | 55(60.0)/37(40.0) | 21(63.6)/12(36.3) | <0.001# |

| Disease Duration (years) | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 9.6 ± 1.0 | NS |

| Disease Distribution Proctitis Left-sided Pan-Colitis |

8 (3.9%) 70 (34.9%) 123 (61.2%) |

9 (9.8%) 25 (27.2%) 58 (63.0%) |

4 (12.1%) 7 (21.2%) 22 (66.6%) |

<0.05# NS NS |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 1.14 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | NS |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 16.3 ± 1.4 | 19.3 ± 1.4 | 25.4 ± 1.6* | <0.05 |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of an Affective Spectrum Disorder |

37 (18.4%) | 11 (12.0%) | 11 (33.3%) | <0.05# |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of IBS | 17 (8.5%) | 18 (19.8%) | 11 (33.3%) | <0.001# |

| Coexisting Diagnosis of a Chronic Pain Syndrome |

44 (21.9%) | 30 (32.6%) | 14 (42.2%) | <0.05# |

| Use of Anti-Depressant Medication |

23 (11.4%) | 17 (18.7%) | 9 (27.2%) | 0.08 |

| Use of Opiate | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (3.3%) | NS |

| Use of NSAID | 17 (8.5%) | 3 (3.3%) | 5 (15.1%) | NS |

| Use of 5-ASA Therapy | 154 (76.6%) | 77 (83.7%) | 25 (75.8%) | NS |

| Use of Immunomodulator Therapy |

63 (31.3%) | 20 (21.7%) | 9 (27.3%) | NS |

| Use of Biologic Therapy | 40 (19.9%) | 15 (16.3%) | 2 (6.1%) | NS |

=p<0.05 compared to control (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni post-test);

=chi-square test).

Discussion

Using a large and well-characterized cohort of patients, we identified pain as an important problem, with at least a moderate burden affecting about one fifth of the patients. Despite this relatively high prevalence of pain, only 3% of our cohort used opioids, a rate that is similar to that reported for the general adult population and substantially lower than previously published for a wide range of other chronic gastrointestinal disorders including Crohn’s disease, chronic pancreatitis, and gastroparesis11, 22–24. We also identified important predictors of pain, which provide insights into possible underlying mechanisms. Pain was more common in patients with active disease and correlated with serological markers of inflammation, pointing at a role of sensitization of visceral afferent pathways and processing due to inflammation and/or inflammatory mediators. However, moderate or severe pain persisted in about 10% of patients with inactive disease. While the retrospective design of our investigation does not allow us to clearly identify the causes of ongoing pain in these patients, the correlations between female gender, mood disorders, chronic pain syndromes and frequent abdominal pain shows significant parallels with functional gastrointestinal disorder25, 26.

Prior investigations have established the importance of inflammation in visceral pain syndromes. Changes in ion channel function and/or expression, synaptic signaling, nerve fiber density and central processing all contribute to hypersensitivity and pain1, 27, 28. Thus, our findings support the current clinical practice of assessing symptomatic patients for underlying and/or inadequately treated colitis. Beyond these more obvious implications, the noted parallels with functional disorders provide interesting information. Other investigators reported a high prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in IBD patients8–11. Based on the retrospective design, we did not rely on common consensus criteria to truly determine the prevalence of IBS or related disorders in our cohort, but instead abstracted comorbid conditions listed by the treating physician, who may or may not have based the diagnoses on accepted diagnostic criteria. Focusing on abdominal discomfort as an important symptom of such disorders only, we noticed a prevalence similar to that reported in previous studies on the functional disorders in IBD in our large outpatient sample. Yet, most of these symptomatic patients continued to have active inflammation, as described above. An increasing number of investigations suggest a potential role of subclinical inflammation in IBS, thus blurring the lines between IBS and IBD18, 29. Despite these provocative results, active disease in UC is obviously defined by more than subclinical inflammation and typically responds to immunosuppressive therapy, which has not yet shown to benefit IBS patients and thus still leaves us with an apparent conceptual divide 30.

Inflammation was not the only predictor of pain in our study. Female predominance and the importance of comorbid mood disorders have been repeatedly shown for pain syndromes, ranging from migraines to interstitial cystitis and functional gastrointestinal disorders25, 31, 32. Interestingly, both factors increased the risk of post-infectious IBS, thus linking inflammation as an inciting peripheral event with central facilitating or perpetuating factors, such as anxiety, catastrophizing and hypervigilance26, 33. A depressive coping style has also been associated with increased pain perception in adults with IBD34. Whether such mechanisms contributed to the ongoing pain in our quiescent UC population cannot be determined due to the retrospective and cross-sectional design of our study.

Considering the emphasis on pain, we also examined pain management in our cohort, focusing on opioid use. With presidential backing, pain has been introduced as the ‘fifth vital sign’ in the routine assessment of patients. Increased awareness about pain and its impact on quality of life led to a tremendous increase in opioid prescriptions within the last decade24. Consistent with this trend, a high number of patients with gastrointestinal disorders are receiving opioids as part of their supportive therapy22, 23. Despite the high prevalence of pain, we did not see a similar pattern in UC patients. The small number of patients on opioids precluded a meaningful assessment of factors influencing opioid use. Yet, only nine out of the 16 patients taking such agents complained about abdominal pain, suggesting that other factors, such as coexisting pain syndromes or non-medical reasons contributed to the use of these agents.

Interestingly, the physician global assessment rating of disease activity was significantly associated with pain. While this may be reassuring for us as healthcare providers, we need to recognize that pain reports and ratings were a part of this assessment. We therefore did not include the SIBDQ and the global physician assessment into our final model, as both would correlate with one of their defining components. Several additional limitations should be considered, when interpreting our results. The study was retrospective and relied on information contained in the electronic medical record. We thus only included information about previously diagnosed mood disorders rather than systematically screening for anxiety and/or depression. The design will have less of an impact on information related to the underlying colitis, because most of our patients are enrolled into clinical trials and have undergone extensive phenotypic characterization. We included endoscopic ratings that were obtained prior to or after the index visit. As pain assessments were routinely obtained during clinic encounters, we cannot rule out that symptoms including pain may have changed. The high number of patients with quiescent disease argues against this as a significant confounder. We also examined potential time-dependent changes in pain ratings and saw a close correlation between ratings obtained prior to and after an endoscopic assessment. By entering multiple variables into our analysis, we may have falsely identified a spurious correlation. In order to minimize a type II error, we only fed variables showing a significant correlation with pain into our final model. The results are consistent with our current understanding of chronic pain, indirectly supporting the appropriateness of our approach. As already indicated, we cannot truly relate our findings to IBS, as the defining consensus criteria were not systematically obtained in this cohort. Information about endoscopic, histological and serological data was abstracted for a time close to the index visit. However, colonoscopies were by definition not performed at the time of that visit and may thus not accurately reflect the degree of inflammation at the time of symptom assessment. As is true for most large cohort studies, we report information obtained in a large tertiary referral center. The data may thus be skewed with a higher fraction of cases involving refractory or more severe inflammation.

In conclusion, our data confirm that abdominal pain is important in UC, affecting a substantial number of patients afflicted with this disorder. While inflammation is a key cause for pain and allows us to target underlying mechanisms in our diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, it is confounded by other factors. The importance of mood disorders provide additional mechanistic insight, it also offers new venues for interventions in UC patients with otherwise unexplained, but persistent symptoms. Overall, these findings suggest that UC patients with pain should be evaluated for active inflammation, even when their disease is considered to be in remission. In the absence of ongoing inflammation, however, management strategies should include interventions that target affective spectrum disorders and functional bowel disorders. Future investigations should examine other potential contributors to pain generation and perpetuation including the role that inflammation may play in modulating not only visceral sensory mechanisms, but also affect, which can in turn influence pain perception.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shari Rogal for her assistance in reviewing this manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant DK063922.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh (IRB Protocol # PRO110169).

References

- 1.Bielefeldt K, Davis B, Binion DG. Pain and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:778–788. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay AR, Hay JW. Inflammatory bowel disease: medical cost algorithms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:318–327. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graff LA, Walker JR, Lix L, et al. The relationship of inflammatory bowel disease type and activity to psychological functioning and quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1491–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyhlen A, Fridell M, Backstrom M, et al. Substance abuse and psychiatric co-morbidity as predictors of premature mortality in Swedish drug abusers: a prospective longitudinal study 1970–2006. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious Infections and Mortality in Association With Therapies for Crohn’s Disease: TREAT Registry. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;4:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunkemeier DM, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, et al. The narcotic bowel syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1126–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.06.013. quiz 1121-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isgar B, Harman M, Kaye MD, et al. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in ulcerative colitis in remission. Gut. 1983;24:190–192. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simren M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minderhoud IM, Oldenburg B, Wismeijer JA, et al. IBS-like symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission; relationships with quality of life and coping behavior. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:469–474. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000020506.84248.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrokhyar F, Marshall JK, Easterbrook B, et al. Functional gastrointestinal disorders and mood disorders in patients with inactive inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and impact on health. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:38–46. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195391.49762.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grover M, Herfarth H, Drossman DA. The Functional-Organic Dichotomy: Postinfectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodhand JR, Wahed M, Mawdsley JE, et al. Mood disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: Relation to diagnosis, disease activity, perceived stress, and other factors. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ibd.22916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crane C, Martin M. Social learning, affective state and passive coping in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones MP, Wessinger S, Crowell MD. Coping Strategies and Interpersonal Support in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;4:474–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naliboff B, Kim S, Bolus R, et al. Gastrointestinal and Psychological Mediators of Health-Related Quality of Life in IBS and IBD: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.377. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simren M, Axelsson J, Gillberg R, et al. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease in remission: the impact of IBS-like symptoms and associated psychological factors. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;97:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keohane J, O’Mahony C, O’Mahony L, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a real association or reflection of occult inflammation? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1788. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.156. 1789-94; quiz 1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5–36. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han S-W, Gregory W, Nylander MBBSD, et al. The SIBDQ: further validation in ulcerative colitis patients. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2000;95:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner D, Griffiths AM, Mack D, et al. Assessing disease activity in ulcerative colitis: Patients or their physicians? Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16:651–656. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross RK, Wilson KT, Binion DG. Narcotic use in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2225–2229. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nusrat S, Yadav D, Bielefeldt K. Pain and opioid use in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2012;41:264–270. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318224056f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan MD, Edlund MJ, Fan MY, et al. Trends in use of opioids for non-cancer pain conditions 2000–2005 in commercial and Medicaid insurance plans: the TROUP study. Pain. 2008;138:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss-Morris R, Spence M. To “Lump” or to “Split” the Functional Somatic Syndromes: Can Infectious and Emotional Risk Factors Differentiate Between the Onset of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Irritable Bowel Syndrome? Psychosom Med. 2006;68:463–469. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221384.07521.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng B, La JH, Schwartz ES, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: methods, mechanisms, and pathophysiology. Neural and neuro-immune mechanisms of visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1085–G1098. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00542.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bielefeldt K, Christianson JA, Davis BM. Basic and clinical aspects of visceral sensation: transmission in the CNS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:488–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arber N, Hallak A, Dotan I, et al. Increased leukocyte adhesiveness/aggregation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during remission. Further evidence for subclinical inflammation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:632–635. doi: 10.1007/BF02056941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of prednisolone in post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2003;18:77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watkins KE, Eberhart N, Hilton L, et al. Depressive disorders and panic attacks in women with bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis: a population-based sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shyti R, de Vries B, van den Maagdenberg A. Migraine genes and the relation to gender. Headache. 2011;51:880–890. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dai C, Jiang M. The incidence and risk factors of post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:67–72. doi: 10.5754/hge10796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mussell M, Bocker U, Nagel N, et al. Predictors of disease-related concerns and other aspects of health-related quality of life in outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:1273–1280. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200412000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]