Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder (BPD) and schizophrenia (SCZ) share clinical characteristics and genetic contributions. Functional dysconnectivity across various brain networks has been reported to contribute to the pathophysiology of both SCZ and BPD. However, research examining resting-state neural network dysfunction across multiple networks to understand the relationship between these two disorders is lacking.

Methods

We conducted a resting-state functional connectivity fMRI study of 35 BPD and 25 SCZ patients, and 33 controls. Using previously defined regions-of-interest, we computed the mean connectivity within and between five neural networks: default mode (DM), fronto-parietal (FP), cingulo-opercular (CO), cerebellar (CER), and salience (SAL). Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to compare groups, adjusting false discovery rate to control for multiple comparisons. The relationship of connectivity with the SANS/SAPS, vocabulary and matrix reasoning was investigated using hierarchical linear regression analyses.

Results

Decreased within-network connectivity was only found for the CO network in BPD. Across groups, connectivity was decreased between CO-CER (p < 0.001), to a larger degree in SCZ than in BPD. In SCZ, there was also decreased connectivity in CO-SAL, FP-CO, and FP-CER, while BPD showed decreased CER-SAL connectivity. Disorganization symptoms were predicted by connectivity between CO-CER and CER-SAL.

Discussion

Our findings indicate dysfunction in the connections between networks involved in cognitive and emotional processing in the pathophysiology of BPD and SCZ. Both similarities and differences in connectivity were observed across disorders. Further studies are required to investigate relationships of neural networks to more diverse clinical and cognitive domains underlying psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Bipolar, Functional connectivity, Networks, Resting state

1. Introduction

Resting state functional connectivity MRI (rs-fcMRI) is based on the premise that spontaneous low-frequency (<0.1 Hz) blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal fluctuations in functionally-related gray matter regions show strong correlations at rest (Biswal et al., 1995). These low frequency BOLD fluctuations appear to relate to spontaneous neural activity (Biswal et al., 1995; Anand et al., 2009; Nir et al., 2006; Leopold et al., 2003). Studies employing rs-fcMRI using graph theory and hierarchical clustering (Anticevic et al., 2012; Dosenbach et al., 2007) or independent component analysis (ICA) (Ongür and Lundy, 2010; Seeley et al., 2007) have shown that the control regions of the brain separate into distinct networks. These networks show high concordance with other measures of structural and functional connectivity in healthy populations (Calhoun et al., 2011; Greicius et al., 2009) and provide an opportunity to characterize distributed circuit abnormalities in neuropsychiatric illnesses (Chai et al., 2011; Fox and Greicius, 2010). In addition, because rs-fcMRI does not require active engagement in a behavioral task, it unburdens experimental design, subject compliance, and training demands.

Several distinct, functionally connected resting state networks have been identified, generally reproducible across different study populations and methodologies. These networks include the default mode, cingulo-opercular, fronto-parietal, dorsal attention, ventral attention, cerebellar, salience, sensorimotor, visual, and auditory networks (Meda et al., 2012; Raichle, 2011; Power et al., 2011). Our previous work (Dosenbach et al., 2007; Repovs et al., 2011; Dosenbach et al., 2008; Repovs and Barch, 2012; Fair et al., 2009) has examined connectivity within and between four of these brain networks thought to be critical for cognitive function: the default mode (DM), the fronto-parietal (FP), the cingulo-opercular (CO), and a cerebellar (CER) network. The DM network is hypothesized to support functions such as self-inspection, future planning, task-independent thought, and attention to internal emotional states; the role of which diminishes during traditional cognitive tasks (Raichle et al., 2001; Broyd et al., 2009; Buckner et al., 2008). The CO network is thought to instantiate and maintain set during task performance, and is believed to detect errors in behavior, thereby signaling the possible need for cognitive strategy adjustment (Dosenbach et al., 2007; Dosenbach et al., 2008; Dosenbach et al., 2006; Fair et al., 2007; Becerril et al., 2011). Regions in the FP network have been referred to as the executive control (Seeley et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2012) network, and this network is thought to incorporate feedback from other networks to make adjustments in processing on later cognitive tasks (Dosenbach et al., 2007; Dosenbach et al., 2008). The CER network shows error related activity in many different types of tasks (Dosenbach et al., 2008; Fair et al., 2007; Becerril et al., 2011). It has been suggested that the cerebellum sends error codes to the CO and FP networks or receives error information from one or both of the these networks (Dosenbach et al., 2008). This role of the CER network is consistent with the view that the cerebellum processes error information to optimize performance (Fornito et al., 2011; Fiez, 1996; Woodward et al., 2011; Fiez et al., 1992).

In addition to these networks, the salience network (SAL), which includes regions of the anterior cingulate (aCC), anterior prefrontal cortex (aPFC), and anterior insula (aI), is thought to play a role in recruiting relevant brain regions for the processing of sensory information (Seeley et al., 2007; Palaniyappan and Liddle, 2012). In schizophrenia, aberrant salience has been proposed as an important mechanism in the production of psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations (White et al., 2010; Palaniyappan et al., 2011). While appearing to overlap with regions in the CO network, the SAL regions have been described as lying anterior and ventral in aCC, lateral in aPFC and dorsal in aI; although evidence for these differentiations are provisional (Power et al., 2011).

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are among the most devastating psychiatric illnesses, and have at least somewhat distinct clinical courses and outcomes. However, they also have substantial overlap in phenomenology (Keshavan et al., 2011), cognition (Glahn et al., 2010; Glahn et al., 2006; Schretlen et al., 2007), brain structure (Arnone et al., 2009; Ellison-Wright and Bullmore, 2010), brain function (Sui et al., 2011) and disease risk genes (Lichtenstein et al., 2009; Berrettini, 2000; Badner and Gershon, 2002). Similarities appear to be higher between schizophrenia and the bipolar patients who have a history of psychosis (Potash et al., 2001; Strasser et al., 2005; Selva et al., 2007). Psychosis, the hallmark of schizophrenia, also affects 50–70% of bipolar patients (Guze et al., 1975; Coryell et al., 2001; Dunayevich and Keck, 2000). Numerous studies have examined functional brain connectivity in schizophrenia during rest states, although results have been variable. For example, both increased (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009; Salvador et al., 2010) and decreased (Camchong et al., 2011; Bluhm et al., 2007; Rotarska-Jagiela et al., 2010) connectivity has been found in the DM network, although the majority of studies have found task-related suppression of the this network (Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2008; Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2009; Hasenkamp et al., 2011; Schneider et al., 2011). SAL network anomalies were also reported by some authors (White et al., 2010) but not found by others (Woodward et al., 2011). In our earlier studies, we found intact connectivity within each of four networks in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected siblings, but found reduced connectivity between CO-FP, the CO-CER, and FP-CER (Repovs et al., 2011; Repovs and Barch, 2012). Additionally, greater connectivity between the FP-CER networks was robustly predictive of better cognitive performance across groups and predictive of fewer disorganization symptoms among patients. Existing rs-fcMRI studies in bipolar disorder show disrupted connections between the prefrontal cortex and limbic related structures, such as the amygdala and temporal lobe (Anand et al., 2009; Chepenik et al., 2010; Dickstein et al., 2010). Using resting-state techniques others have reported that individuals with bipolar disorder show reduced connectivity within the DMN network (Calhoun et al., 2008), the pregenual anterior cingulate, thalamus and amygdala (Anand et al., 2009). Anticevic et al. (2012) found that bipolar patients exhibited increased amygdala-medial prefrontal cortex connectivity, and reduced connectivity between amygdala and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, both of which were associated with psychosis history.

Few studies have examined functional networks in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Chai et al. (2011) reported a decoupling of DLPFC and MLPC connectivity in both schizoprhenia and bipolar disorder. These authors also found in bipolar disorder, an increased connectivity of MLPFC with both insula and VLPFC, which were not seen schizophrenia patients or controls. Ongür and Lundy (2010) compared the DMN network in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and found that both had less DM network connectivity in medial prefrontal cortex. Meda et al. (2012) reported both shared resting-state network connectivity in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder between fronto/occipital and anterior default mode/PFC regions, as well as unique patterns of connectivity in each disorder.

The goal of the current study was to examine alterations in functional connectivity within and between the DM, FP, CO, CER and SAL networks, and explore similarities across bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, and can provide insight into pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders, which have been increasingly associated with neural network dysfunction (Zorumski and Rubin, 2011). We hypothesized that subjects with bipolar disorder will have a lesser degree of dyconnectivity in regions primarily involved in cognition (i.e. FP, CO and CER networks), while DM and SAL network connectivity would be abnormal primarily in schizophrenia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

The participants (Table 1) for this study were recruited through the Conte Center for the Neuroscience of Mental Disorders at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis included: (1) individuals with DSM-IV Schizophrenia (SCZ; N=25), (2) individuals with DSM-IV Bipolar Disorder (BPD; N=35), and (3) healthy controls (N=33). The SCZ and control participants were the same participants reported on in our previous paper on resting state connectivity (Repovs et al., 2011). All participants gave written informed consent for participation. The individuals with SCZ and BPD were all outpatients, and clinically stable for at least two weeks. Controls were required to have no lifetime history of Axis I psychotic or mood disorders and no first-degree relatives with a psychotic disorder.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Measure | Group | Group comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls (CON) | Individuals with schizophrenia (SCZ) | Individuals with bipolar disorder (BPD) | F or χ2 | p value | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age | 22.8b | 2.94 | 24.4 | 3.07 | 24.9b | 3.75 | 3.8 | < 0.05 |

| Gender (% male) | 59.4% | – | 73.1% | – | 45.7% | – | 4.62 | 0.10 |

| Education | 13.9a | 1.8 | 12.2a,c | 1.8 | 14.1c | 2.4 | 7.6 | < 0.01 |

| Parental education | 14.7b | 1.6 | 14.3c | 2.2 | 16.2b,c | 2.9 | 5.7 | < 0.01 |

| Negative symptoms | 0.70a,b | 1.0 | 8.9a,c | 3.4 | 3.74b,c | 3.1 | 68.6 | < 0.001 |

| Positive symptoms | 0.03a,b | 0.2 | 3.6a,c | 3.2 | 1.1b,c | 1.9 | 22.2 | < 0.001 |

| Disorganization symptoms | 1.2a,b | 1.4 | 3.5a | 2.7 | 2.5b | 2.0 | 9.9 | < 0.001 |

| Vocabulary | 47.3a,b | 9.0 | 38.8a,c | 8.8 | 53.1b,c | 11.4 | 15.1 | < 0.001 |

| Matrix reasoning | 56.0a | 1.2 | 49.6a,c | 8.8 | 54.9c | 9.5 | 4.4 | < 0.05 |

CON ≠ SCZ.

CON ≠ BPD.

SCZ ≠ BPD.

All subjects were diagnosed on the basis of a consensus between a research psychiatrist who conducted a semi-structured interview and a trained research assistant who used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al., 2001). Participants were excluded if they: (a) met DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence or severe/moderate abuse during the prior 6 months; (b) had a clinically unstable or severe general medical disorder; (c) had a history of head injury with documented neurological sequelae or loss of consciousness; or (d) met DSM-IV criteria for mental retardation.

2.2. Clinical and cognitive assessments

Psychopathology in all participants was assessed using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen et al., 1986). Scores from these measures were grouped into subscales for positive symptoms (hallucinations and delusions), disorganization (formal thought disorder, bizzare behavior and attention), and negative symptoms (flat affect, alogical, anhedonia and amotivation).

Cognition was assessed using the vocabulary and matrix reasoning subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS)/Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) vocabulary measure).

2.3. fMRI scanning

All scanning occurred on a 3T Tim TRIO Scanner at Washington University Medical School. Functional images (BOLD) were acquired using an asymmetric spin-echo, echo-planar sequence (T2*) (repetition time [TR]=2500 ms, echo time [TE]=27 ms, field of view [FOV]=256 mm, flip=90°, voxel size=4 × 4 × 4 mm). Resting state data were acquired from each participant for two BOLD runs in which participants rested quietly with their eyes closed. Each run contained 164 images, for a total of 328 images and 13.7 min of resting state activity. In addition, a T1 structural image was acquired using a sagittal MP-RAGE 3D sequence (TR=2400 ms, TE=3.16 ms, flip=8°; voxel size=1 × 1 × 1 mm).

2.4. fcMRI data preprocessing

Basic imaging data preprocessing included: (1) compensation for slice-dependent time shifts; 2) removal of first five images from each run during which BOLD signal was allowed to reach steady state; (3) elimination of odd/even slice intensity differences due to interpolated acquisition; (4) realignment of data within and across runs to compensate for rigid body motion (Ojemann et al., 1997); (5) intensity normalization to a whole brain mode value of 1000; (6) registration of the 3D structural volume (T1) to the atlas representative template in the Talairach coordinate system (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988) using a 12-parameter affine transform; and (7) co-registration of the 3D fMRI volume to the structural image and transformation to atlas space using a single affine 12-parameter transform that included a re-sampling to a 3 mm cubic representation.

To improve signal-to-noise, remove baseline and possible sources of spurious correlations, all images were further preprocessed in steps that included: (1) spatial smoothing using a gaussian kernel with 3 voxels FWHR, (2) high-pass filtering with 0.009 Hz cutoff frequency, (3) removal of nuisance signal that included six rigid body motion correction parameters, ventricle, white matter, and whole brain signals, as well as their first derivatives. All connectivity analyses were conducted on residual timeseries after removal of listed regressors. The two BOLD timeseries (excluding the first five frames) were concatenated to form a single timeseries. The initial BOLD preprocessing was accomplished using in-house software, fcMRI preprocessing and analyses described below were performed using custom Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts) code.

2.5. Quality control and movement assessment

A frequent confound in imaging studies with clinical populations is that the clinical group moves more, which can lead to lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the acquired resting state data, and perhaps also apparent reductions in connectivity. Thus, we took two approaches to addressing movement related confounds. First, as a last preprocessing step, frames with excessive movement and movement-related intensity changes were identified and excluded from further analysis. Bad frames were identified following a modified procedure suggested by Power et al. (2012) as those that met at least one of the two criteria. First, frames in which sum of the displacement across all six rigid body movement correction parameters exceeded 0.5 mm were identified. Second, root mean square (RMS) of differences in intensity between the current and preceding frame was computed across all voxels and divided by mean intensity. Frames in which normalized RMS was more than 1.6 the median across the run were identified. The identified frames, one preceding and two following frames were then marked for exclusion in computation of functional connectivity. A repeated measures ANOVA for the percentage of eliminated frames, with group (control, SCZ, BPD) as a between subject factor, indicated that there was a significant group difference in the number of frames eliminated, (F(190)=6.17, p=0.003, η2=0.12), with both SCZ (M=38, SD=34) and BPD (M=28, SD=29) having more frames eliminated than CON (M=14, SD=15), but no significant differences between the two patient groups. We then examined the RMS of intensity differences across frames as a measure of signal quality post movement scrubbing. There was still a significant difference across groups in this measure, (F(190)=3.92, p=0.02, η2=0.08), with both SCZ (M=16.2, SD=2.98) and BPD (M=16.34, SD=2.57) having higher RMS than CON (M=14.7, SD=2.20), but no significant differences between the two patient groups. Thus, we also examined whether group differences in the analyses presented below remained when controlling for this RMS measure.

2.6. Network region definition

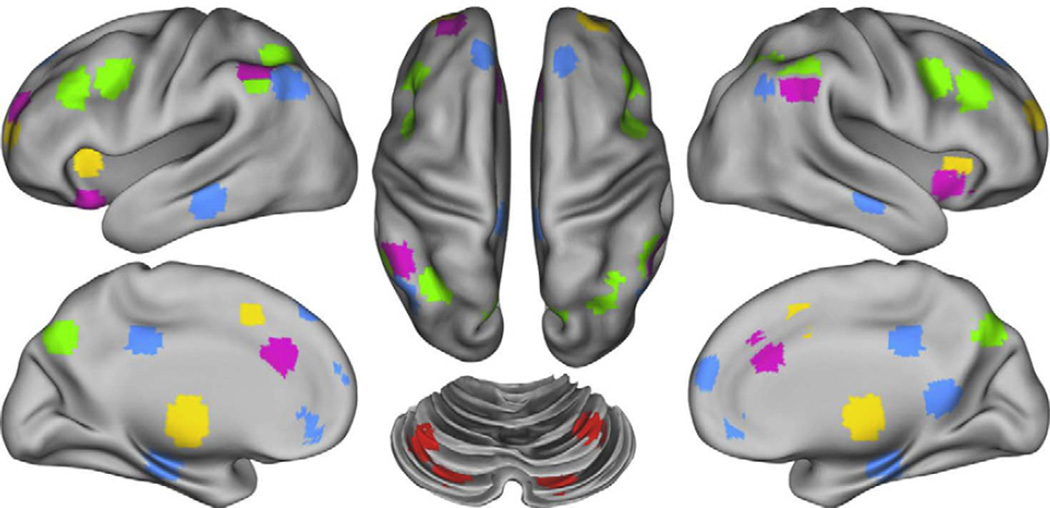

We examined regions included in the DM network as defined by Fox et al. (2005), and regions included in the FP, CO and CER networks as defined by Dosenbach et al. (2007). In addition, we included regions in the SAL network as defined by Power et al. (2011). To control for individual anatomical variability, regions of interest were defined for each individual in two steps. First, we created spherical ROIs in standard Talairach space centered on the reported coordinates for each region (Fig. 1) and 15 mm in diameter. Second, we masked the resulting group ROIs with the individual FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/ version 4.1.0) segmentation of a high-resolution structural image that was previously registered to standard Talairach space, excluding any voxels within the group defined ROIs that did not represent the relevant gray matter (cerebral cortex, cerebellar cortex, hippocampus, thalamus) in the specific individual, as defined by FreeSurfer (Fischl et al., 2002).

Fig. 1.

Figure illustrating the location of regions within each of the five networks. Regions of the Frontal-Parietal network (FP) are marked in green, the Cingulo-Opercular network (CO) in yellow, the Default Mode Network (DMN) in blue the Cerebellar network (CER) in red and the Salience network (SAL) in purple.

2.7. Data analysis

We extracted the time series for each of the ROIs described above and computed the ROI–ROI correlation matrix for each participant. For further analysis we converted the correlations to Fisher z values using Fisher r-to-Z transform and used these as the dependent measure. For every individual, we computed the average connectivity (mean Fisher z value) across all ROI–ROI connections between each network. We denoted within network averages as wDMN, wFP, wCO, wCER, and wSAL, and between network connectivity averages as bDMN-FP, bDMN-CO, bDMN-CER, bDMN-SAL, bFP-CO, bFP-CER, bFP-SAL, bCO-CER, bCO-SAL, and bCER-SAL. Separate mixed-design ANOVAs were then used to estimate group related differences in the resulting measures of within and between network connectivity. For the sake of brevity, we do not report main effects or interactions that do not include group. Significant effects were further explored with planned comparisons, using False Discovery Rate to control for multiple comparisons, to isolate the source of significant ANOVA effects. Statistical analysis was conducted using R (Team, 2011) and visualized using ggplot2 library (Wickham, 2009).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

The three groups differed significantly in age, years in school, and parental education. As shown in Table 1, the BPD were significantly younger than controls, with no differences between SCZ and either controls or BPD. The SCZ had fewer years of education than either the controls or the BPD, who did not differ from each other. The BPD had greater parental education than either controls or SCZ, who did not differ from each other. Because age and parental education differed in BPD versus controls or SCZ, all significant results below were confirmed both using age and parental education as covariates, and in subgroups that did not differ in either age or parental education. In addition, as expected the groups differed in positive, negative and disorganization symptoms, as well as both vocabulary and matrix reasoning performance. The controls had fewer symptoms of all types than both SCZ and BPD. In addition, SCZ had higher negative and positive symptoms than BPD, though they did not differ in disorganization symptoms. The SCZ had lower vocabulary scores than controls, and the controls had lower vocabulary scores than BPD. The SCZ had lower matrix reasoning scores than controls and BPD, who did not differ from each other.

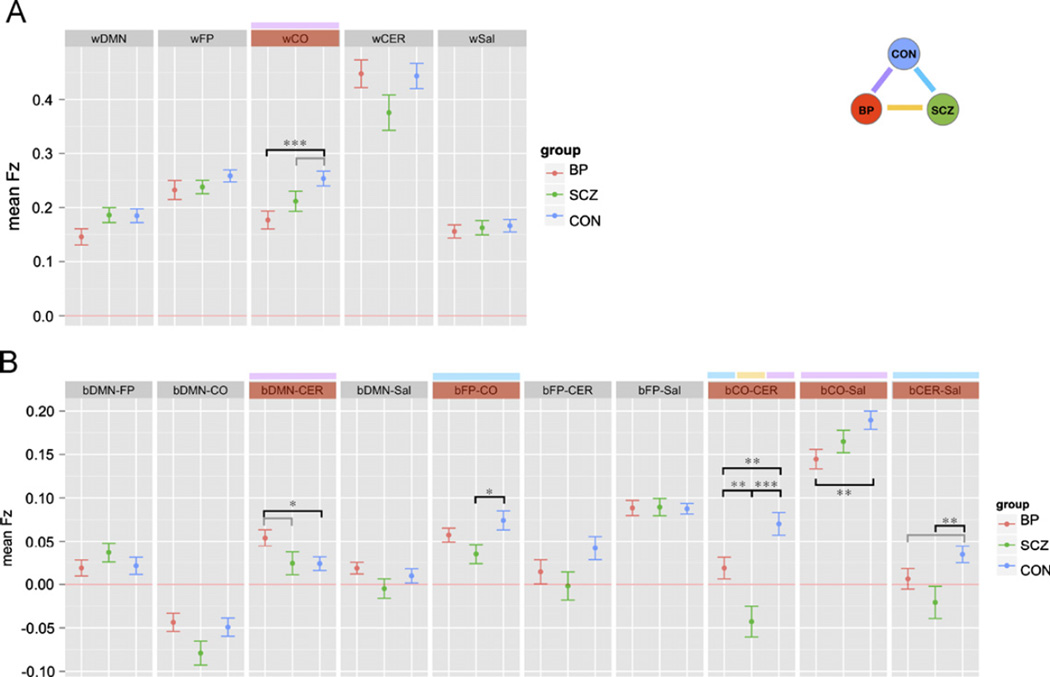

3.2. Within network connectivity

The within-network ANOVA included diagnostic group as a between-subject factor, and network as a within subject factor. This ANOVA revealed a trend level main effect of diagnostic group (F(290)=2.91, p=0.06), a significant main effect of network (F(4360)=131.20, p < 0.001) as well as a significant diagnostic group × network interaction (F(8360)=2.31, p < 0.05). To determine the source of this interaction, we conducted follow-up ANOVAs for each network to determine which showed main effects of group. As shown in Fig. 2A, wCO showed a significant main effect of diagnostic group, (F(290)=6.36, p < 0.01). This group difference remained significant both when covarying for age and parental education and when comparing subgroups that did not differ significantly in age or parental education. Post hoc contrasts indicated that the controls showed significantly greater wCO connectivity than the BPD (p=0.001) with a similar trend for SCZ (p=0.07). However, SCZ and BPD did not differ significantly (p=0.15).

Fig. 2.

Graph illustrating within (A) and between (B) network connectivity in each of the three groups: SCZ = individuals with schizophrenia; BP = bipolar disorder; CON = healthy controls. DMN = Default Mode Network; FP = Frontal Parietal Network; CO = Cingulo-Opercular Network; CER = Cerebellar Network; SAL = Salient Network. Segments marked in red indicate networks for which connectivity measures showed significant overall group differences. Above these segments, color-coding indicates the specific groups showing differences (purple = bipolar disorder and healthy controls; yellow = schizophrenia and bipolar disorder; blue = schizophrenia and healthy controls). * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001gray bar, no asterisk = p < 0.1.

3.3. Between network connectivity

Next we examined between-network connectivity using the same analysis approach. This ANOVA revealed significant main effects of diagnostic group (F(290)=7.43, p=0.001) and network (F(9810)=92.17, p < 0.001), as well as a significant interaction between diagnostic group and network (F(18,810)=3.79, p < 0.001). To determine the source of this interaction, we conducted follow-up ANOVAs for each network to determine which showed main effects of group. As shown in Fig. 2B, bDMN-CER (F(290)=3.14, p=0.05), bFP-CO (F(290)=3.52, p < 0.05), bCO-CER (F(290)=14.7, p < 0.001), bCO-SAL (F(290)=4.17, p < 0.05), and bCER-Sal (F(290)=4.22, p < 0.05) all showed significant main effects of diagnostic group. bFP-CER group differences showed only trend level significance (p=0.1).

The group differences in bFP-CO, bCO-CER, bCO-SAL and bCER-SAL all remained significant both when covarying for age and parental education and when comparing subgroups that did not differ significantly in age or parental education. However, the group difference in bDMN-CER was no longer significant when covarying for age and parental education (F(188)=2.20, p=0.12) or in the matched subgroups (F(184)=2.33, p=0.10). We also examined whether these group differences remained when covarying for the RMS measure of signal variation associated with movement (see Methods for details). The group differences in bCO-CER, bCO-SAL and bCER-SAL all remained significant when covarying for the RMS measures. The group differences in bFP-CO was p=0.055.

Post hoc contrasts indicated that for bCO-CER, connectivity was significantly higher for controls compared to both SCZ and BPD (ps < 0.01). For bCO-SAL, connectivity was significantly higher in controls compared to BPD (p < 0.01), but not SCZ (p=0.12). For bFP-CO, bFP-CER and bCER-SAL, connectivity was significantly higher in controls compared to SCZ (p < 0.05), but not BPD (p40.10). The two patient groups did not differ significantly on bCO-CER, bCO-SAL, bFP-CER or bCER-SAL.

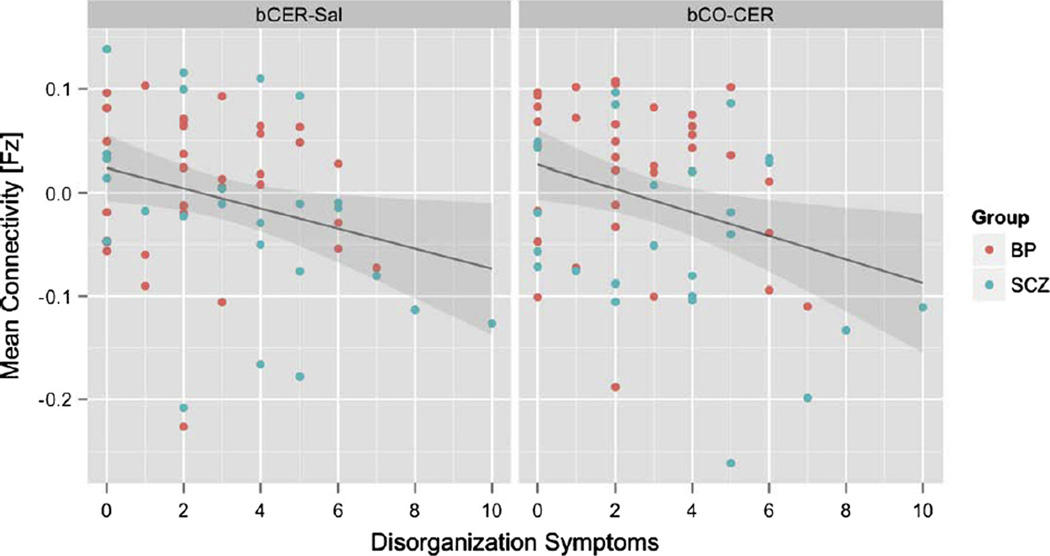

3.4. Relationship to clinical variables

To examine whether individual differences in connectivity in any of the regions showing group differences predicted individual differences in clinical symptoms, we used hierarchical linear regression analyses. In step one for each model; we entered diagnosis (SCZ vs BPD) and the connectivity measure to predict either positive, negative or disorganization symptoms. In step two, we entered an interaction term between diagnosis and the connectivity measure. None of the connectivity measures predicted negative symptoms or positive symptoms. However, both bCO-CER (β= −0.28, p < 0.05) and bCER-Sal (β= −0.26 p < 0.05) predicted disorganization symptoms, with higher connectivity (more similar to controls) predicting reduced disorganization (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Relationship of mean cerebellar-salience network connectivity (left) and mean cingulo-opercular-cerebellar network connectivity (right) with disorganization symptoms in individuals with bipolar disorder (red dots) and schizophrenia (blue dots). Gray shading indicates standard error.

There was no relationship between vocabulary and matrix reasoning scores on the WASI and any of the regions showing significant group differences in connectivity.

4. Discussion

Our study showed varying degrees of both within- and between-network dysconnectivity across bipolar disorder (BPD) and schizophrenia (SCZ) patients. Within-network dysconnectivity was only seen in the cingulo-opercular (CO) network, with BPD patients showing decreased CO within-network connectivity compared to controls. CO within-network connectivity in SCZ patients was intermediate between that of controls and BPD patients, although it did not differ significantly from either of these groups. The CO network has been reported to play a major role in stable task-set maintenance and error processing (Dosenbach et al., 2008; Fair et al., 2007), with decreased functioning of this network resulting in an impaired ability to alter cognitive control. Both SCZ and BPD has been associated with impaired neuropsychological performance (Lewandowski et al., 2011; Yatham et al., 2010; Barch, 2009; Stefanopoulou et al., 2009; Dickerson et al., 2004), although generally greater impairment is seen in SCZ in multiple cognitive domains (Barch, 2009; Stefanopoulou et al., 2009; Dickerson et al., 2004). This may indicate that CO network impairment observed in BPD patients is related to functions other than cognitive performance. The CO network includes the dorsal ACC attributed to cognition, however there is some functional overlap with the ventral ACC that is involved in modulation of emotional responses (Allman et al., 2001; Bush et al., 2000). Reviewing both animal and human studies, Etkin et al. (2011) reported that both dorsal and ventral ACC have roles in emotional processing, with dorsal regions involved in appraisal and expression of negative emotion. The anterior insula, another part of the CO network, has prominent connections to the limbic regions and has been implicated in emotional processing (Nieuwenhuys, 2012). Thus, the major role of the CO network may be that of emotion regulation or processing and not cognition, as has been suggested. Prior studies in BPD have not investigated resting state connectivity within regions corresponding to the CO network, to our knowledge. On the other hand, decreased connectivity within the CO network in SCZ has been previously reported (Tu et al., 2012), however that study also included the putamen as part of the CO network. Functional disconnection within regions corresponding to the CO network in schizophrenia has also been reported during task-based fMRI (White et al., 2010; Tu et al., 2010). The CO network is of particular interest, as its two hubs—the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and the anterior insula are unique in containing large numbers of von Economo neurons, which are spindle-shaped bipolar projection neurons in layer V of the cortex found only in humans and great apes (Allman et al., 2011a,b; Fajardo et al., 2008). This suggests a more recent evolution of the CO network associated with higher-level cognitive or emotional processing.

We did not find within-network connectivity in any other of the regions studied in either SCZ or BPD. Alterations in within network connectivity however have been reported by other authors in regions corresponding to FP network (Fornito et al., 2011; Woodward et al., 2011) and DM network (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009; Salvador et al., 2010; Bluhm et al., 2007; Rotarska-Jagiela et al., 2010) in SCZ, and the DM network (Ongür and Lundy 2010; Calhoun et al., 2011) in BPD. It is possible that factors such as stage of illness may have influenced our results. Our patients were relatively younger and earlier in the course of illness compared with patients that had altered connectivity in some (Camchong et al., 2011; Bluhm et al., 2007; Rotarska-Jagiela et al., 2010), although not all (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009), other studies.

In our between-network analyses, connectivity of the CO network with the CER network was found to be abnormal in both the SCZ and BDP groups. Impaired CO-CER connectivity which was present in both SCZ and BPD may have major implications in cognitive adaptation and coordination, owing to the role of CER in learning from errors, and in the timing and sequencing of a range of cognitive functions (Fiez, 1996; Fiez et al., 1992; Ravizza et al., 2006; Ben-Yehudah et al., 2007; Strick et al., 2009; Durisko and Fiez, 2010). Our previous studies found that the unaffected siblings of individuals with SCZ also showed consistent reductions in connectivity between both the FP and CO networks with the CER network (Repovs et al., 2011; Repovs and Barch, 2012), a finding that was similar in magnitude across rest and all levels of working memory load (Repovs and Barch, 2012). This suggests that CO-CER connectivity is a stable characteristic, and may be involved in the genetic liability to schizophrenia, and potentially even to BPD. CO-CER functional connectivity in BPD has not previously been studied, to our knowledge. Genetic overlap of BPD with SCZ however exists (Lichtenstein et al., 2009; Berrettini, 2000; Badner and Gershon, 2002; Potash, 2006), and may partly explain the reported similarities in dysconnectivity between these networks.

We also found significant group differences in FP-CO connectivity. However, post-hoc analysis showed that these results were driven by decreased connectivity in SCZ compared to controls. Decreased FP-CO and FP-CER network connectivities were also found in both SCZ and their unaffected siblings in our prior connectivity study (Repovs et al., 2011), suggesting that these network dysconnectivities may also genetically predispose to the disorder. The current study found that while in the BPD patients FP-CO and FP-CER connectivity is intermediate between that of SCZ and control groups, these differences with other groups were not significant.

We also report an abnormal connectivity of the SAL network with the CO and CER networks. Decreased connections between the SAL and CO networks were significant only in BPD patients; while those with the CER were significant only in SCZ subjects. The SAL network is believed to be involved in salience detection, with abnormalities leading to reality distortion in psychotic states (White et al., 2010; Palaniyappan et al., 2011). The clinical significance of these findings should however be interpreted cautiously. The SAL network includes brain regions overlapping with the CO network, which has different functions, and anatomical distinctions between networks have not been reliably established (Power et al., 2011).

Minor changes in our results were also found after co-varying for age and parental education status. Most notably, DMN-CER between-network connectivity differences became non-significant. Controlling separately for each of those covariates indicated that most of the initial group differences in DMN-CER connectivity was driven by age differences across groups, with the BPD group consisting of the youngest subjects. While functional connectivity has been reported to increase from childhood into adulthood (Fair et al., 2009; Power et al., 2010; Dosenbach et al., 2010), between-network connectivity weakens with age in favor of within-network connectivity (Dosenbach et al., 2010; Stevens et al., 2009). Thus the presence of increased DMN-CER in the bipolar subjects appears to be related to increased functional integration in younger age, and not due to group differences in connectivity across these networks. Other studies have also found reduced connectivity between regions in CO, FP and CER networks (Zhou et al., 2007; Shen et al., 2010), and studies showing reduced connectivity between DMN and regions in CO or FP networks have also been reported (Zhou et al., 2007; Jafri et al., 2008).

We found an association of decreased CO-CER and CER-SAL connectivity with increasingly disorganized symptoms. However, there was no relationship between any network connectivity and either positive or negative symptoms. Disorganized symptoms which involve formal thought disorder, attention difficulties, and bizarre delusion have been more closely associated with neurocognitive symptoms than positive psychotic symptoms (Ventura et al., 2010). This would be consistent with our results, considering the role of the CO and CER in cognitive functioning. Our previous study, which included the same SCZ patients as in this study as well as their unaffected siblings (Repovs et al., 2011), showed a correlation between executive functioning scores with FP-CER across groups. Association between cognitive network function and clinical characteristics in SCZ has however been variable across studies. Dysfunction of a variety of brain networks has been linked to cognitive performance (Lynall et al., 2010), disorganization (Lui et al., 2009; Lagioia et al., 2010), positive symptoms (Meda et al., 2012; Bluhm et al., 2007; Rotarska-Jagiela et al., 2010; Lagioia et al., 2010; Venkataraman et al., 2012; Henseler et al., 2010), negative symptoms (Bluhm et al., 2007; Lui et al., 2009; Lagioia et al., 2010; Venkataraman et al., 2012), and mania (Ongür and Lundy, 2010), suggesting that pathophysiology may involve a complex dysconnectivity involving multiple different brain networks. Further studies would therefore be required to investigate the association of cognitive performance with specific network dysconnectivities found in our current study.

There are several limitations to the current study. Both SCZ and BPD patients were medicated, and differences in medication use across groups could influence our findings. Resting state functional connectivity across neural networks have been found to be reduced by antipsychotic (Lui et al., 2010; Sambataro et al., 2010) and antidepressant (McCabe et al., 2011) medications. However, similarities in several findings with that previously found in unaffected siblings (Repovs et al., 2011), who were not taking any antipsychotic medications, suggests medication effects on connectivity findings are minimal. We also could not control for the arousal level of our participants during the resting state scans, and it is possible that arousal levels differed across groups. However, given our focal pattern of connectivity differences across groups, global changes in arousal as a factor contributing to group differences is less likely to be a confounding factor.

In summary, we found decreased resting-state connectivity within the CO network in bipolar disorder, as well as decreased between-network connectivity involving the CO, FP, CER and SAL to various degrees in SCZ and BPD patients. Among between-network connectivities, that between CO and CER showed the greatest group difference, with connectivity in BPD patients being intermediate to that of SCZ patients and controls. Impairment across the involved networks would be expected to affect efficient cognitive and emotional functioning in SCZ and BPD; however to establish this association more research is needed. Future network connectivity studies also involving other brain networks would also enhance understanding of the clinical pathophysiology of these disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Administrative/Assessment and Biostatistical Cores of the CCNMD at Washington University School of Medicine for collection of the clinical and imaging data and data management.

Role of funding source

Dr. Mamah has received grants from the NIMH and NARSAD. Dr. Barch has received grants from the NIMH, NIA, NARSAD, Allon, Novartis, and the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience and has consulted for Pfizer. Dr. Repovš is a consultant on NIMH grants.

This research was supported by NIH grants P50 MH071616, R01 MH56584 and K08 MH085948.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts.

References

- Allman JM, Hakeem A, Erwin JM, Nimchinsky E, Hof P. The anterior cingulate cortex. The evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;935:107–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Manaye KF, Semendeferi K, Erwin JM, et al. The von Economo neurons in the frontoinsular and anterior cingulate cortex. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011a;1225:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Park S. The von Economo neurons in apes and humans. American Journal of Human Biology. 2011b:5–21. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A, Li Y, Wang Y, Lowe MJ, Dzemidzic M. Resting state corticolimbic connectivity abnormalities in unmedicated bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. Psychiatry Research. 2009;171(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Grove WM. Evaluation of positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Psychobiology. 1986;1:108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Anticevic A, Brumbaugh MS, Winkler AM, Lombardo LE, Barrett J, Corlett PR, et al. Global prefrontal and fronto-amygdala dysconnectivity in bipolar I disorder with psychosis history. Biological Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, Cavanagh J, Gerber D, Lawrie SM, Ebmeier KP, McIntosh AM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):194–201. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badner JA, Gershon ES. Meta-analysis of whole-genome linkage scans of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7(4):405–411. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM. Neuropsychological abnormalities in schizophrenia and major mood disorders: similarities and differences. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11(4):313–319. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerril KE, Repovs G, Barch DM. Error processing network dynamics in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):1495–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehudah G, Guediche S, Fiez JA. Cerebellar contributions to verbal working memory: beyond cognitive theory. Cerebellum. 2007;6(3):193–201. doi: 10.1080/14734220701286195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini WH. Susceptibility loci for bipolar disorder: overlap with inherited vulnerability to schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;47(3):245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34(4):537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm RL, Miller J, Lanius RA, Osuch EA, Boksman K, Neufeld RWJ, et al. Spontaneous low-frequency fluctuations in the BOLD signal in schizophrenic patients: anomalies in the default network. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(4):1004–1012. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyd SJ, Demanuele C, Debener S, Helps SK, James CJ. Sonuga-Barke EJS. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: a systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009;33(3):279–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Luu P, Posner M. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2000;4(6):215–222. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01483-2. Regul. Ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Maciejewski PK, Pearlson GD, Kiehl KA. Temporal lobe and default hemodynamic brain modes discriminate between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Human Brain Mapping. 2008;29(11):1265–1275. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Sui J, Kiehl K, Turner J, Allen E, Pearlson G. Exploring the psychosis functional connectome: aberrant intrinsic networks in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:75. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camchong J, MacDonald AW, Bell C, Mueller BA, Lim KO. Altered functional and anatomical connectivity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2011;37(3):640–650. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai XJ, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Shinn AK, Gabrieli JDE, Nieto-Castanon A, McCarthy JM, et al. Abnormal medial prefrontal cortex resting-state connectivity in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(10):2009–2017. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chepenik LG, Raffo M, Hampson M, Lacadie C, Wang F, Jones MM, et al. Functional connectivity between ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala at low frequency in the resting state in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2010;182(3):207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Leon AC, Turvey C, Akiskal HS, Mueller T, Endicott J. The significance of psychotic features in manic episodes: a report from the NIMH collaborative study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;67(1–3):79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson F, Boronow JJ, Stallings C, Origoni AE, Cole SK, Yolken RH. Cognitive functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: comparison of performance on the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Gorrostieta C, Ombao H, Goldberg LD, Brazel AC, Gable CJ, et al. Fronto-temporal spontaneous resting state functional connectivity in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(9):839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NUF, Visscher KM, Palmer ED, Miezin FM, Wenger KK, Kang HC, et al. A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron. 2006;50(5):799–812. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NUF, Fair DA, Miezin FM, Cohen AL, Wenger KK, Dosenbach RAT, et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(26):11073–11078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NUF, Fair DA, Cohen AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends in Cognitive. 2008;12(3):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.001. Regul. Ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NUF, Nardos B, Cohen AL, Fair DA, Power JD, Church JA, et al. Prediction of individual brain maturity using fMRI. Science. 2010;329(5997):1358–1361. doi: 10.1126/science.1194144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevich E, Keck PE. Prevalence and description of psychotic features in bipolar mania. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2000;2(4):286–290. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durisko C, Fiez JA. Functional activation in the cerebellum during working memory and simple speech tasks. Cortex. 2010;46(7):896–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison-Wright I, Bullmore E. Anatomy of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;117(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(2):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004. Regul. Ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Cohen AL, Brahmbhatt S, Miezin FM, et al. Development of distinct control networks through segregation and integration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(33):13507–13512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705843104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Cohen AL, Power JD, Dosenbach NUF, Church JA, Miezin FM, et al. Functional brain networks develop from a local to distributed organization. PLOS Computational Biology. 2009;5(5):e1000381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo C, Escobar MI, Buriticá E, Arteaga G, Umbarila J, Casanova MF, et al. Von economo neurons are present in the dorsolateral (dysgranular) prefrontal cortex of humans. Neuroscience Letters. 2008;435(3):215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiez JA. Cerebellar contributions to cognition. Neuron. 1996;16(1):13–15. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiez JA, Petersen SE, Cheney MK, Raichle ME. Impaired non-motor learning and error detection associated with cerebellar damage. A single case study. Brain. 1992;115(Pt 1):155–178. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33(3):341–355. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito A, Yoon J, Zalesky A, Bullmore ET, Carter CS. General and specific functional connectivity disturbances in first-episode schizophrenia during cognitive control performance. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;70(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Greicius M. Clinical applications of resting state functional connectivity. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2010;4:19. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(27):9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Bearden CE, Cakir S, Barrett JA, Najt P, Serap Monkul E, et al. Differential working memory impairment in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: effects of lifetime history of psychosis. Bipolar Disorder. 2006;8(2):117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Almasy L, Barguil M, Hare E, Peralta JM, Kent JW, et al. Neurocognitive endophenotypes for bipolar disorder identified in multiplex multigenerational families. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):168–177. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19(1):72–78. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Clayton PJ. The significance of psychotic affective disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1975;32(9):1147–1150. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760270079009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenkamp W, James GA, Boshoven W, Duncan E. Altered engagement of attention and default networks during target detection in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;125(2–3):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler I, Falkai P, Gruber O. Disturbed functional connectivity within brain networks subserving domain-specific subcomponents of working memory in schizophrenia: relation to performance and clinical symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44(6):364–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafri MJ, Pearlson GD, Stevens M, Calhoun VD. A method for functional network connectivity among spatially independent resting-state components in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2008;39(4):1666–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Morris DW, Sweeney JA, Pearlson G, Thaker G, Seidman LJ, et al. A dimensional approach to the psychosis spectrum between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: the schizo-bipolar scale. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;133(1–3):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DI, Manoach DS, Mathalon DH, Turner JA, Mannell M, Brown GG, et al. Dysregulation of working memory and default-mode networks in schizophrenia using independent component analysis, an fBIRN and MCIC study. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30(11):3795–3811. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagioia A, Van De Ville D, Debbané M, Lazeyras F, Eliez S. Adolescent resting state networks and their associations with schizotypal trait expression. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2010:4. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold DA, Murayama Y, Logothetis NK. Very slow activity fluctuations in monkey visual cortex: implications for functional brain imaging. Cerebral Cortex. 2003;13(4):422–433. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski KE, Cohen BM, Ongür D. Evolution of neuropsychological dysfunction during the course of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(2):225–241. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710001042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, et al. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373(9659):234–239. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui S, Deng W, Huang X, Jiang L, Ma X, Chen H, et al. Association of cerebral deficits with clinical symptoms in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia: an optimized voxel-based morphometry and resting state functional connectivity study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(2):196–205. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui S, Li T, Deng W, Jiang L, Wu Q, Tang H, et al. Short-term effects of antipsychotic treatment on cerebral function in drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia revealed by resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(8):783–792. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynall M-E, Bassett DS, Kerwin R, McKenna PJ, Kitzbichler M, Muller U, et al. Functional connectivity and brain networks in schizophrenia. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(28):9477–9487. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0333-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe C, Mishor Z, Filippini N, Cowen PJ, Taylor MJ, Harmer CJ. SSRI administration reduces resting state functional connectivity in dorso-medial prefrontal cortex. Molecular Psychiatry. 2011;16(6):592–594. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Gill A, Stevens MC, Lorenzoni RP, Glahn DC, Calhoun VD, et al. Differences in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging functional network connectivity between schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar probands and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Biological Psychiatry. 2012:6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuys R. The insular cortex: a review. Progress in Brain Research. 2012;195:123–163. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nir Y, Hasson U, Levy I, Yeshurun Y, Malach R. Widespread functional connectivity and fMRI fluctuations in human visual cortex in the absence of visual stimulation. Neuroimage. 2006;30(4):1313–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojemann JG, Akbudak E, Snyder AZ, McKinstry RC, Raichle ME, Conturo TE. Anatomic localization and quantitative analysis of gradient refocused echo-planar fMRI susceptibility artifacts. Neuroimage. 1997;6(3):156–167. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongür D, Lundy M, Greenhouse I, Shinn AK, Menon V, Cohen BM, et al. Default mode network abnormalities in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2010;183(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palaniyappan L, Liddle PF. Does the salience network play a cardinal role in psychosis? An emerging hypothesis of insular dysfunction. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2012;37(1):17–27. doi: 10.1503/jpn.100176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palaniyappan L, Mallikarjun P, Joseph V, White TP, Liddle PF. Reality distortion is related to the structure of the salience network in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(8):1701–1708. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomarol-Clotet E, Salvador R, Sarroó S, Gomar J, Vila F, Martínez A, et al. Failure to deactivate in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: dysfunction of the default mode network? Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(8):1185–1193. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomarol-Clotet E, Canales-Rodríguez EJ, Salvador R, Sarró S, Gomar JJ, Vila F, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex pathology in schizophrenia as revealed by convergent findings from multimodal imaging. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15(8):823–830. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash JB. Carving chaos: genetics and the classification of mood and psychotic syndromes. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2006;14(2):47–63. doi: 10.1080/10673220600655780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash JB, Willour VL, Chiu YF, Simpson SG, MacKinnon DF, Pearlson GD, et al. The familial aggregation of psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder pedigrees. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1258–1264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Fair DA, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. The development of human functional brain networks. Neuron. 2010;67(5):735–748. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72(4):665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Barnes KA, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME. The restless brain. Brain Connect. 2011;1(1):3–12. doi: 10.1089/brain.2011.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(2):676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravizza SM, McCormick CA, Schlerf JE, Justus T, Ivry RB, Fiez JA. Cerebellar damage produces selective deficits in verbal working memory. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 2):306–320. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repovs G, Barch DM. Working memory related brain network connectivity in individuals with schizophrenia and their siblings. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012;6:137. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repovs G, Csernansky JG, Barch DM. Brain network connectivity in individuals with schizophrenia and their siblings. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69(10):967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotarska-Jagiela A, van de Ven V, Oertel-Knöchel V, Uhlhaas PJ, Vogeley K, Linden DEJ. Resting-state functional network correlates of psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;117(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador R, Sarró S, Gomar JJ, Ortiz-Gil J, Vila F, Capdevila A, et al. Overall brain connectivity maps show cortico-subcortical abnormalities in schizophrenia. Hum Brain Mapping. 2010;31(12):2003–2014. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambataro F, Blasi G, Fazio L, Caforio G, Taurisano P, Romano R, et al. Treatment with olanzapine is associated with modulation of the default mode network in patients with Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(4):904–912. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider FC, Royer A, Grosselin A, Pellet J, Barral F-G, Laurent B, et al. Modulation of the default mode network is task-dependant in chronic schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;125(2–3):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schretlen DJ, Cascella NG, Meyer SM, Kingery LR, Testa SM, Munro CA, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(2):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selva G, Salazar J, Balanzá-Martínez V, Martínez-Arán A, Rubio C, Daban C, et al. Bipolar I patients with and without a history of psychotic symptoms: do they differ in their cognitive functioning? Journal of Psychiatry Research. 2007;41(3–4):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H, Wang L, Liu Y, Hu D. Discriminative analysis of resting-state functional connectivity patterns of schizophrenia using low dimensional embedding of fMRI. Neuroimage. 2010;49(4):3110–3121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanopoulou E, Manoharan A, Landau S, Geddes JR, Goodwin G, Frangou S. Cognitive functioning in patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 2009;21(4):336–356. doi: 10.1080/09540260902962149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MC, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD. Changes in the interaction of resting-state neural networks from adolescence to adulthood. Hum Brain Mapping. 2009;30(8):2356–2366. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser HC, Lilyestrom J, Ashby ER, Honeycutt NA, Schretlen DJ, Pulver AE, et al. Hippocampal and ventricular volumes in psychotic and nonpsychotic bipolar patients compared with schizophrenia patients and community control subjects: a pilot study. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(6):633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick PL, Dum RP, Fiez JA. Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:413–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui J, Pearlson G, Caprihan A, Adali T, Kiehl KA, Liu J, et al. Discriminating schizophrenia and bipolar disorder by fusing fMRI and DTI in a multimodal CCA + joint ICA model. Neuroimage. 2011;57(3):839–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.05.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. New York: Thieme; 1988. p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Team RDC. Foundation for statistical computing. Vienna: 2011. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Tu P, Buckner RL, Zollei L, Dyckman KA, Goff DC, Manoach DS. Reduced functional connectivity in a right-hemisphere network for volitional ocular motor control in schizophrenia. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 2):625–637. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu P-C, Hsieh J-C, Li C-T, Bai Y-M, Su T-P. Cortico-striatal disconnection within the cingulo-opercular network in schizophrenia revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity analysis: a resting fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2012;59(1):238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataraman A, Whitford TJ, Westin C-F, Golland P, Kubicki M. Whole brain resting state functional connectivity abnormalities in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;139(1–3):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Thames AD, Wood RC, Guzik LH, Hellemann GS. Disorganization and reality distortion in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the relationship between positive symptoms and neurocognitive deficits. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;121(1–3):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TP, Joseph V, Francis ST, Liddle PF. Aberrant salience network (bilateral insula and anterior cingulate cortex) connectivity during information processing in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;123(2–3):105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy Science of the United States of America. 2009;106(4):1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward ND, Rogers B, Heckers S. Functional resting-state networks are differentially affected in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2011;130(1–3):86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C, Bai F, Yu H, Shi Y, Yuan Y, Chen G, et al. Abnormal insula functional network is associated with episodic memory decline in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage. 2012;63(1):320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatham LN, Torres IJ, Malhi GS, Frangou S, Glahn DC, Bearden CE, et al. The international society for bipolar disorders-battery for assessment of neurocognition (ISBD-BANC) Bipolar Disorder. 2010;12(4):351–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Liang M, Jiang T, Tian L, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Functional dysconnectivity of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in first-episode schizophrenia using resting-state fMRI. Neuroscience Letters. 2007;417(3):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Liang M, Tian L, Wang K, Hao Y, Liu H, et al. Functional disintegration in paranoid schizophrenia using resting-state fMRI. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;97(1–3):194–205. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorumski CF, Rubin EH. Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. Oxford Univ Pr; 2011. p. 300. [Google Scholar]