Abstract

Objective:

There has been limited research examining the association between mental health symptoms, perceived peer alcohol norms, and alcohol use and consequences among samples of adolescents. The current study used a sample of 193 at-risk youths with a first-time alcohol and/or other drug offense in the California Teen Court system to explore the moderating role of perceived peer alcohol norms on the association between mental health symptoms and drinking outcomes.

Method:

Measures of drinking, consequences, mental health symptoms, and perceived peer alcohol norms were taken at baseline, with measures of drinking and consequences assessed again 6 months later. Regression analyses examined the association of perceived norms and mental health symptoms with concurrent and future drinking and consequences.

Results:

We found that higher perceived drinking peer norms were associated with heavy drinking behavior at baseline and with negative alcohol consequences both at baseline and 6 months later. Also, perceived drinking norms moderated the association between mental health symptoms and alcohol-related consequences such that better mental health was related to increased risk for alcohol-related consequences both concurrently and 6 months later among those with higher baseline perceptions of peer drinking norms.

Conclusions:

Findings demonstrate the value of norms-based interventions, especially among adolescents with few mental health problems who are at risk for heavy drinking.

Alcohol use is common among adolescents in the United States, with approximately 27% of 10th graders and 40% of 12th graders reporting having drunk alcohol within the past 30 days (Johnston et al., 2012). Approximately one third of 8th through 12th graders report having been drunk at some point in their lives, and nearly 22% of high school seniors report having consumed five or more drinks in a row during the past 2 weeks (Johnston et al., 2012). Heavy drinking has been linked to current problems, such as poor physical health (Arria et al., 1995) and risky sexual behavior (Fergusson and Lynskey, 1996), as well as to future problems, such as dropping out of school, criminal and violent behavior, health problems, and risk for developing alcohol use disorders (Hill et al., 2000; McCambridge et al., 2011; Oesterle et al., 2004; Tucker et al., 2005).

Many adolescents also may struggle with mental health concerns during this developmental period, with depressive and anxiety symptoms being reported the most frequently (Knopf et al., 2008). Several studies have shown that adolescent depressive and anxiety symptoms are linked with heavier drinking and with experiencing problems from alcohol use (Chan et al., 2008; Clark et al., 1997; Kandel et al., 1999). Poor mental health in adolescence also may lead to the development of increased alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in young adulthood (McKenzie et al., 2011). For example, poorer mental health in late adolescence (age 18 years) has been shown to predict alcohol dependence 11 years later (D’Amico et al., 2005).

The “self-medication hypothesis” may partially explain the association between mental health and drinking. This hypothesis proposes that individuals with depressive or anxiety symptoms may engage in drinking to reduce negative affect and anxiety (Khantzian, 1985). Although literature supports this hypothesis in research with adult and college student samples (e.g., Geisner et al., 2004; 2012; Petrakis et al., 2002; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011; Weitzman, 2004), research findings are mixed on how mental health may affect drinking behavior among adolescents with general levels of depression and anxiety that may not reach clinical levels. Some studies support the self-medication theory in adolescence, such that depressive and anxiety symptoms have been shown to precede rather than result from drinking across the transition from middle to late adolescence (e.g., Mason et al., 2009). In contrast, findings from other work demonstrate that adolescents increase their use of substances (e.g., illicit drugs, alcohol, cigarettes) during their high school years regardless of their level of depression or anxiety symptoms (Hooshmand et al., 2012; Needham, 2007). Furthermore, adolescent boys with more mental health symptoms were less likely to be classified as heavy drinkers, compared with those with limited mental health symptoms (Theunissen et al., 2011). Other work has found a link between depressive symptoms and drinking for adolescent females but not for males (Fleming et al., 2008; Strandheim et al., 2009).

Longitudinal research is therefore needed to understand how experiencing anxiety and depressive symptoms (vs. having a disorder) may affect drinking among racially and ethnically diverse at-risk adolescents, as the majority of studies have been with older adolescents (e.g., college students) and have used primarily White samples. It also is important to understand factors that may moderate this association. For example, the social aspect of drinking is especially salient for adolescents, and studies have shown that, for this age group, drinking occurs primarily in social settings (Fleming et al., 2008; Hooshmand et al., 2012). Moreover, adolescents who report fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms tend to have more friends and report more opportunities to drink alcohol (Crowe et al., 1998; Hsu and Reid, 2012).

Adolescents with fewer anxiety and depressive symptoms may therefore have greater exposure to drinking, which could affect their perceived peer norms. Perceived norms are adolescents’ beliefs about their peers’ drinking behavior—specifically, how often and how much they believe their peers drink. These beliefs are particularly salient for youths, because peer approval and acceptance are highly important in adolescence, with both classic and current research findings suggesting that these beliefs are associated with increases in drinking behavior (Akers et al., 1979; Brown et al., 2008; Christiansen et al., 1982; Page et al., 2002; Perkins and Craig, 2003) as well as their intentions to drink heavily (Olds et al., 2005).

Perceived norms also are associated with consequences from use. For example, high school students with higher perceived norms of their peers’ drinking behavior were more likely to report driving while alcohol impaired, riding with an alcohol-impaired driver, and experiencing one or more negative consequences because of drinking, compared with those with lower perceived norms (Beck and Treiman, 1996). Correcting perceived peer drinking norms has been an efficacious focus of interventions with adolescents (Brown, 2001; D’Amico et al., 2012; Haines et al., 2003; Hansen and Graham, 1991), and a continued examination of the factors associated with perceived norms can help inform further intervention efforts.

At-risk youths who have engaged in delinquent behavior are more likely to report heavy alcohol use and consequences (D’Amico et al., 2008; Mason et al., 2007, 2009) and often are caught for offenses that occur within a social context (e.g., drinking in public with friends; D’Amico et al., in press). Thus, this group may have more opportunities for perceived norms to influence their drinking behavior. They have more experience observing their peers through social learning processes by which to formulate ideas about behavior within their environment. Given that more social youths also tend to have better mental health (Goodman et al., 2001; La Greca and Harrison, 2005), one might expect that perceived norms would influence the association between mental health symptoms and alcohol use outcomes among at-risk youths, such that youths with better mental health and higher perceived norms are more likely to drink heavily and to experience more consequences from alcohol use. To date, there have been no studies examining the role of perceived norms as a moderator of the association between mental health symptoms and alcohol use among at-risk adolescents. Research has only just begun to assess the link between perceived norms and social anxiety among college students (Buckner et al., 2011; LaBrie et al., 2008; Neighbors et al., 2007).

The current study therefore took an important first step, using a longitudinal design to examine whether at-risk adolescents’ perceived norms moderate the association between depressive and anxiety symptoms and drinking outcomes (frequency of use, heavy use, consequences). First, we assessed the association between symptoms and drinking outcomes. We hypothesized that adolescents who reported more mental health symptoms (i.e., poorer mental health) at baseline would report more drinking and alcohol-related consequences at both baseline and 6 months later. Second, we looked at the association between baseline reports of perceived drinking norms on alcohol use and consequences. We hypothesized that perceived norms would be associated with drinking behavior and consequences at baseline and greater drinking and consequences 6 months later. Finally, we examined perceived norms as a moderator of the association between mental health symptoms and drinking and consequences. We hypothesized that better mental health symptoms and higher perceived peer drinking norms reported at baseline would be associated with more drinking and consequences at baseline, as well as greater drinking and consequences 6 months later.

Method

Participants

The participants were part of a randomized controlled study comparing a group motivational interviewing (Miller and Rollnick, 2012) intervention (Free Talk) to standard care within the teen court system (D’Amico et al., in press). Youths were recruited by research staff members between January 2009 and October 2011 from the Santa Barbara County Teen Court, a juvenile diversion program offered by the Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse. Teens were referred to the program by the county juvenile probation department because they had not been found in need of more serious intervention such as treatment or detention. The teen court program offers alcohol and other drug education for youths with first-time alcohol and/or other drug offenses (e.g., possession of alcohol or other drugs, driving under the influence, driving with an open container). In our sample, the most common types of offenses included drinking and using marijuana in public locations with peers. Alcohol made up 56% of the cases, and marijuana made up 38%, with the remainder of youths cited for concurrent alcohol and marijuana use infractions (4%) or other drug offenses (2%).

Of the 216 eligible youths who were asked to consider being a part of the study by the research staff, 193 agreed and were randomly assigned to either usual care or our motivational interviewing group intervention. Twenty-three parents/youths (11%) refused to participate in the study, most commonly because of lack of interest or time. There were no demographic differences between those who refused and those who participated in the study. Participants completed baseline measures, and 97% completed a follow-up assessment 6 months later. In this sample, 67% were male and 45% reported Hispanic ethnicity (54% non-Hispanic White). The mean age of participants was 16.64 years (SD = 1.05), and their ages ranged from 14 to 18 years at the baseline assessment.

Procedure

Procedures were approved by the institution’s internal review board. Study staff members recruited adolescents between ages 14 and 18 years who had been referred to the teen court program for a first-time alcohol or other drug offense. Eligible youths interested in participating provided assent and had their parents provide consent for participation. We obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health and made it clear to participants that their data were confidential and would be used for research purposes and not for any civil, criminal, administrative, legislative, or other proceedings, whether state, federal, or local. The researchers in the field collecting data explained that they did not work for the Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse, the Santa Barbara Probation Department, or the teen court system. Thus, information obtained as part of the research project would not be used against them in legal proceedings. Participants completed a baseline survey before their teen court hearing and attended six group meetings over an approximately 90-day period. A follow-up assessment was completed approximately 3 months after group completion (i.e., 6 months after baseline). Participants were offered monetary incentives for survey completion ($25 for baseline survey and $45 for the follow-up survey).

Measures.

Participants completed measures of demographic information, drinking behavior, alcohol-related consequences, perceived peer drinking norms, and mental health symptoms. Demographic information included items about age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences.

Items from the RAND Adolescent/Young Adult Panel Study (Ellickson et al., 2001; Tucker et al., 2003) assessed the frequency of drinking (i.e., “at least one drink of alcohol”) and the frequency of heavy drinking (i.e., “five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours”) in the past month at both baseline and follow-up. Eight response options ranged from 0 days to 21 to 30 days. Six items from these prior studies also were included to assess alcohol-related consequences (e.g., missed school or work, passed out) (α = .81 for baseline; α = .73 for follow-up). Four response options ranged from never to three or more times.

Perceived peer drinking norms.

Perceived norms were assessed at baseline with a single item asking participants to indicate how many days in the past month they thought “a typical teen your age had at least one drink of alcohol.” Response options matched the options for their own frequency of drinking and heavy drinking days. This item was modified from those used in prior work with adolescents to capture perceived drinking days of adolescent peers (see California Healthy Kids Survey; WestEd, 2008).

Mental Health Inventory.

Mental health symptoms at baseline were assessed with the five-item Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5; Berwick et al., 1991). The MHI-5 measures general mental health by assessing the frequency (1 = all the time to 6 = never) of five domains of mental health. These domains include anxiety (“How much of the time have you been a very nervous or anxious person?”), general positive affect (“How much of the time have you felt calm or peaceful?”), depression (“How much of the time have you felt downhearted or blue?”), general positive affect (“How much of the time have you been a happy person?”), and behavioral/emotional control (“How often have you felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up?”). The MHI-5 is particularly indicated as a brief measure of depressive symptoms and feelings of anxiety (Rumpf et al., 2001; Yamazaki et al., 2005) and has been used in surveys with adolescents (Tanielian et al., 2009; Theunissen et al., 2011). The two general positive-affect items are reverse coded and summed with the other three items to give a composite score on the scale range from 5 to 30, with higher scores indicating better overall mental health. This composite score and individual items were examined in analyses. Internal consistency of the MHI-5 composite in the present sample was adequate (α = .81).

Results

Analytic plan

We conducted a series of cross-sectional and longitudinal regression analyses. Time 1 refers to the baseline survey, and Time 2 refers to the follow-up survey. We ran a series of regression analyses with six separate outcome variables of alcohol-related consequences (Time 1 and Time 2), the number of drinking days (Time 1 and Time 2), and the number of heavy drinking days (Time 1 and Time 2). In each series, we first ran a model with the baseline MHI-5 composite score, the number of baseline perceived drinking days (i.e., perceived norms), and the MHI-5 Score × Perceived Norms interaction term. If we found a statistically significant effect for the MHI-5 composite, we followed up with analyses to look at the individual MHI-5 items from baseline that might be influencing effects concurrently (Time 1) and predicting future behavior (Time 2). For this, we ran each series with each of the individual MHI-5 items (anxiety, general positive affect [calm/peaceful], depression, general positive affect [happy], behavioral/emotional control) separately in an analysis with the number of perceived drinking days and the interaction between the MHI-5 Item × Perceived Norms.

We initially evaluated outcomes by gender but did not find any interaction effects between gender and predictors (MHI-5, perceived norms); nor did we find any interaction effects between ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic) and predictors on outcomes. Age, gender, ethnicity, and intervention condition (Free Talk vs. standard care) were included as covariates in all analyses. Table 1 provides a correlation matrix with means and standard deviations for all variables.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix with means and standard deviations of variables included in analyses

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. |

| 1. MHI-5 composite | – | |||||||||||||

| 2. Perceived drinking days | -.08 | – | ||||||||||||

| 3. MHI-5 (anxiety) | .75 | -.12 | – | |||||||||||

| 4. MHI-5 (general positive affect—calm/peaceful) | -.70 | .08 | -.34 | – | ||||||||||

| 5. MHI-5 (depression) | .80 | -.06 | .51 | -.44 | – | |||||||||

| 6. MHI-5 (general positive affect—happy) | -.75 | .03 | -.40 | .59 | -.46 | – | ||||||||

| 7. MHI-5 (behavioral/emotional control) | .77 | .01 | .54 | -.32 | .61 | -.46 | – | |||||||

| 8. Time 1 drinking days | -.05 | .47 | .05 | .11 | -.03 | .09 | -.02 | – | ||||||

| 9. Time 2 drinking days | -.01 | .30 | -.06 | .04 | .06 | .05 | .04 | .41 | – | |||||

| 10. Time 1 consequences | -.15 | .33 | -.01 | .16 | -.14 | .11 | -.14 | .61 | .33 | – | ||||

| 11. Time 2 consequences | -.11 | .18 | -.16 | .05 | -.08 | .01 | -.10 | .22 | .49 | .27 | – | |||

| 12. Age | .08 | .21 | .14 | .05 | .03 | -.04 | .15 | .27 | .24 | .12 | .03 | – | ||

| 13. Racea | -.05 | -.07 | -.04 | -.01 | .01 | .03 | -.13 | -.05 | -.11 | .06 | .04 | -.2.5 | – | |

| 14. Genderb | .19 | -.15 | .15 | -.24 | .16 | -.09 | .09 | -.16 | -.03 | -.05 | -.11 | .01 | -.01 | – |

| M or % | 3.11 | 4.16 | 4.32 | 2.65 | 4.39 | 2.48 | 4.98 | 2.51 | 2.57 | 1.23 | 1.17 | 16.64 | 45.08%c | 67.36%d |

| SD | 0.90 | 1.57 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.61 | 1.54 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 1.05 | – | – |

Notes: Correlations at or above 0.14 are significant at p < .05; MHI-5 = five-item Mental Health Inventory.

0 = non-Hispanic, 1 = Hispanic;

0 = female, 1 = male;

percentage of males;

percentage of Hispanic ethnicity.

Alcohol-related consequences

Table 2 provides regression results for alcohol-related consequences outcomes at Time 1 and Time 2. The number of perceived drinking days was significantly associated with consequences at Time 1 (p = .002), and the interaction term for MHI-5 × Perceived Norms also was significant (p = .041). In addition, the number of baseline perceived drinking days had a unique effect on consequences at Time 2 (p = .003), as did the interaction term for Baseline MHI-5 × Baseline Perceived Norms (p = .017). Figure 1 displays the MHI-5 × Perceived Norms interaction effect on alcohol-related consequences at Time 2. The Time 1 effect displayed a similar trend and was not graphed for parsimony of results presentation. Overall, better mental health and higher perceived drinking norms at Time 1 were associated with higher reported consequences at both Time 1 and Time 2.

Table 2.

Regression analyses for alcohol consequences outcome

| Outcome: Alcohol-related consequences | Estimate | SE | p | |

| Time 1 Model | ||||

| Overall mental health | MHI-5 | -.06 | .03 | .110 |

| Perceived norms | .23 | .07 | .002 | |

| MHI-5 × Perceived Norms | -.05 | .00 | .041 | |

| Anxiety | MHI-5 (anxiety) | .01 | .03 | .816 |

| Perceived norms | .14 | .07 | .033 | |

| MHI-5 (anxiety) × Perceived Norms | -.01 | .01 | .383 | |

| Calm/peaceful | MHI-5 (calm/peaceful) | -.05 | .03 | .067 |

| Perceived norms | .19 | .07 | .005 | |

| MHI-5 (calm/peaceful) × Perceived Norms | -.02 | .01 | .103 | |

| Depression | MHI-5 (depression) | -.05 | .02 | .045 |

| Perceived norms | .37 | .08 | .000 | |

| MHI-5 (depression) × Perceived Norms | -.06 | .02 | .000 | |

| Happy | MHI-5 (happy) | -.06 | .03 | .054 |

| Perceived norms | .24 | .09 | .013 | |

| MHI-5 (happy) × Perceived Norms | -.03 | .02 | .096 | |

| Emotional/behavioral control | MHI-5 (emotional/behavioral control) | -.05 | .02 | .078 |

| Perceived norms | .13 | .07 | .092 | |

| MHI-5 (emotional/behavioral control) × Perceived Norms | -.01 | .02 | .522 | |

| Time 2 Model | ||||

| Overall mental health | MHI-5 | -.02 | .02 | .525 |

| Perceived norms | .17 | .06 | .003 | |

| MHI-5 × Perceived Norms | -.04 | .02 | .017 | |

| Anxiety | MHI-5 (anxiety) | -.02 | .02 | .229 |

| Perceived norms | .16 | .06 | .004 | |

| MHI-5 (anxiety) × Perceived Norms | -.04 | .02 | .019 | |

| Calm/peaceful | MHI-5 (calm/peaceful) | .00 | .02 | .974 |

| Perceived norms | .14 | .05 | .004 | |

| MHI-5 (calm/peaceful) × Perceived Norms | -.02 | .01 | .030 | |

| Depression | MHI-5 (depression) | -.01 | .02 | .541 |

| Perceived norms | -.13 | .06 | .054 | |

| MHI-5 (depression) × Perceived Norms | -.02 | .01 | .176 | |

| Happy | MHI-5 (happy) | -.02 | .02 | .499 |

| Perceived norms | .17 | .07 | .023 | |

| MHI-5 (happy) × Perceived Norms | -.03 | .02 | .077 | |

| Emotional/behavioral control | MHI-5 (emotional/behavioral control) | -.02 | .02 | .359 |

| Perceived norms | .10 | .06 | .107 | |

| MHI-5 (emotional/behavioral control) × Perceived Norms | -.01 | .01 | .328 | |

Notes: MHI-5 = five-item Mental Health Inventory score. SE = standard error. Significant effects are bolded.

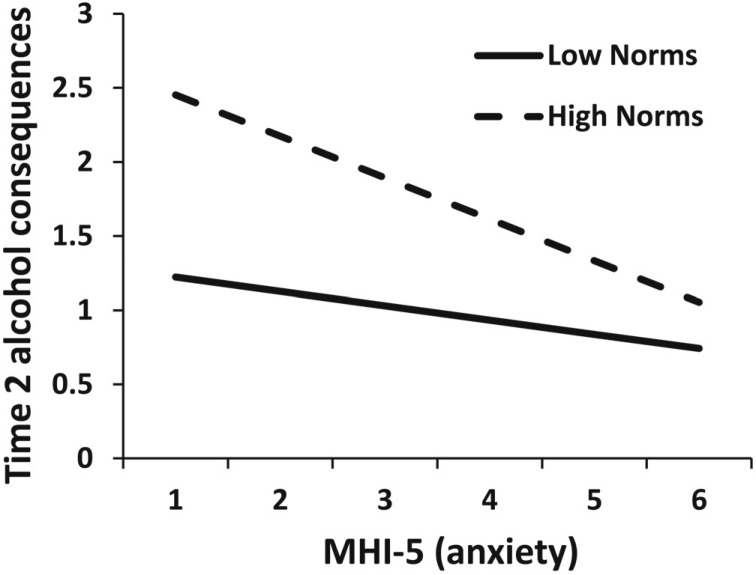

Figure 1.

Interaction between the five-item Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) score and perceived norms for alcohol consequences at Time 2. Note: Higher values on X-axis indicate better mental health (i.e., less frequency of distress).

Because the interaction terms for the composite MHI-5 × Perceived Norms were significant at both Time 1 and Time 2 for alcohol-related consequences, we evaluated the unique effects of each of the MHI-5 items (i.e., anxiety, general positive affect [calm/peaceful], depression, general positive affect [happy], behavioral/emotional control), the number of perceived drinking days, and their interaction with alcohol-related consequences at Time 1 and Time 2.

Anxiety.

We found a statistically significant effect for Time 1 alcohol-related consequences and the number of perceived drinking days (p = .033). At Time 2, there were statistically significant unique effects for the number of perceived drinking days (p = .004) and the interaction term for MHI-5 (anxiety) × Perceived Norms (p = .019). Figure 2 displays the MHI-5 (anxiety) × Perceived Norms interaction effect on alcohol-related consequences at Time 2. Participants who reported less anxiety and higher perceived norms also reported more alcohol-related consequences.

Figure 2.

Interaction between anxiety subscale score and perceived norms for Time 2 alcohol consequences. MHI-5 = five-item Mental Health Inventory. Note: Higher values on X-axis indicate higher frequency of anxiety symptoms (1 = never and 6 = always).

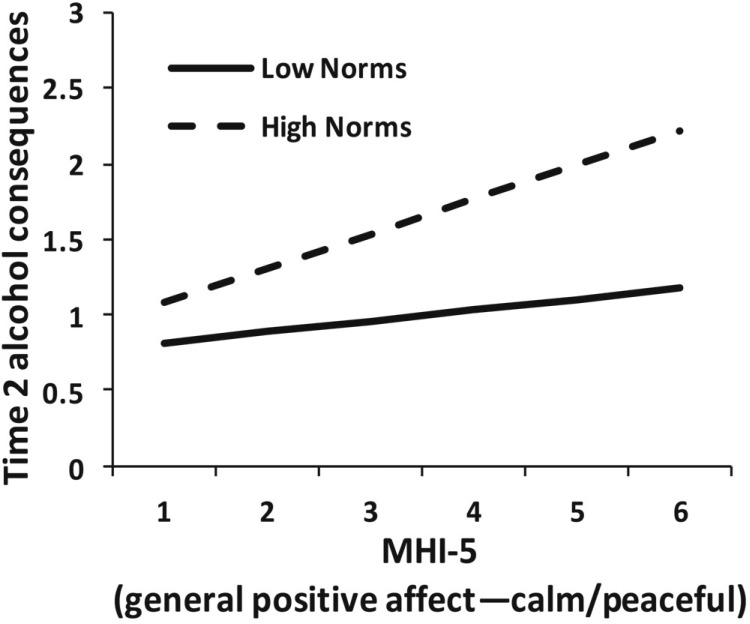

General positive affect (calm/peaceful).

At Time 1, the number of perceived drinking days was a statistically significant predictor of consequences (p = .005). The model for Time 2 alcohol consequences showed statistically significant effects for the number of perceived drinking days (p = .004), as did the interaction term for MHI-5 (calm/peaceful) × Perceived Norms (p = .030). Figure 3 displays the MHI-5 (calm/peaceful) × Perceived Norms interaction effect on alcohol-related consequences at Time 2. Those who reported feeling calm or peaceful more frequently and who also reported higher perceived norms tended to report experiencing more alcohol-related consequences.

Figure 3.

Interaction between general positive affect subscale score and perceived norms for Time 2 alcohol consequences. MHI-5 = five-item Mental Health Inventory. Note: Higher values on X-axis indicate higher frequency of feelings of calmness/peacefulness (1 = never and 6 = always).

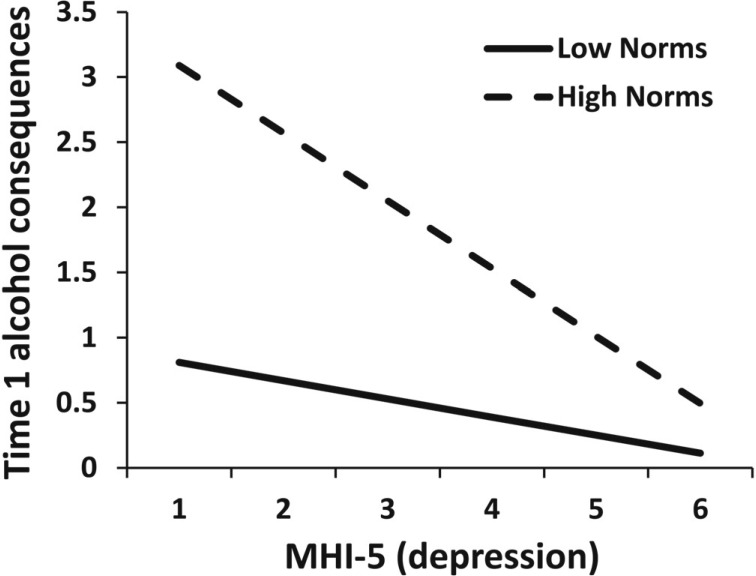

Depression.

Time 1 alcohol-related consequences were significantly predicted by MHI-5 (depression) (p = .045), the number of perceived drinking days (p < .001), and the interaction term for MHI-5 (depression) × Perceived Norms (p < .001). Figure 4 displays the MHI-5 (depression) × Perceived Norms interaction effect on alcohol-related consequences at Time 1, with participants who reported less depression and higher perceived norms reporting more alcohol-related consequences. The model predicting Time 2 consequences was not significant.

Figure 4.

Interaction between depression subscale score and perceived norms for Time 1 alcohol consequences. MHI-5 = five-item Mental Health Inventory. Note: Higher values on X-axis indicate higher frequency of depression symptoms (1 = never and 6 = always).

General positive affect (happy).

Only the number of perceived drinking days had a unique effect on alcohol-related consequences at Time 1 (p = .013). MHI-5 (happy) had a marginally significant effect on these consequences (p = .054), showing that higher positive affect was associated with fewer consequences. The model predicting Time 2 consequences was not significant.

Emotional/behavioral control.

Both Time 1 and Time 2 models were not significant.

Frequency of drinking

Drinking days.

There were no statistically significant estimates in the model predicting the number of drinking days at Time 1 or Time 2 from the composite MHI-5, the number of perceived drinking days, or the composite MHI-5 × Perceived Norms (Table 3). Thus, we did not examine follow-up effects for individual MHI-5 items.

Table 3.

Regression analyses for drinking frequency outcomes

| Variable | Estimate | SE | p | |

| Outcome: Drinking days | ||||

| Time 1 model | ||||

| Overall mental health | MHI-5 | -.06 | .12 | .636 |

| Perceived norms | .43 | .26 | .104 | |

| MHI-5 × Perceived Norms | .00 | .08 | .995 | |

| Time 2 model | ||||

| Overall mental health | MHI-5 | -.01 | .13 | .914 |

| Perceived norms | .38 | .27 | .165 | |

| MHI-5 × Perceived Norms | -.03 | .08 | .706 | |

| Outcome: Heavy drinking days | ||||

| Time 1 model | ||||

| Overall mental health | MHI-5 | .07 | .12 | .545 |

| Perceived norms | .60 | .25 | .020 | |

| MHI-5 × Perceived Norms | -.07 | .08 | .373 | |

| Time 2 model | ||||

| Overall mental health | MHI-5 | .04 | .12 | .705 |

| Perceived norms | .43 | .25 | .085 | |

| MHI-5 × Perceived Norms | -.04 | .07 | .559 | |

Notes: MHI-5 = Mental Health Inventory score. SE = standard error. Significant effect is bolded. We did not run follow-up tests for the number of drinking days or the number of heavy drinking days because interactions between the full MHI-5 composite score and the perceived norms interaction terms were nonsignificant for either outcome variable.

Heavy drinking days.

The model predicting the Time 1 number of heavy drinking days showed a unique significant effect for the number of perceived drinking days (p = .020). The MHI-5 composite and the interaction term were both nonsignificant; therefore, we did not examine follow-up effects for individual MHI-5 items. The model at Time 2 was nonsignificant with no unique effects for any of the variables (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the association between mental health symptoms and perceived peer alcohol use norms and their relation to alcohol use and consequences among an at-risk sample of primarily Hispanic and White adolescents. Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not find a significant direct effect for mental health symptoms on drinking behavior or consequences. Therefore, our results did not provide support for the self-medication hypothesis. One reason for this finding may be that we looked at symptoms instead of a diagnosis, and, overall, our sample reported few depressive and anxiety symptoms and a moderately high positive affect. Other studies have found an association between alcohol use and poor mental health symptoms in adolescent samples; however, those studies have typically included more severe populations such as those in substance use treatment (e.g., Chan et al., 2008).

We also found that perceived norms were associated with current heavy drinking and consequences as well as future heavy alcohol use and consequences. These findings contribute to the empirical support for perceived peer norms about drinking as a consistent risk factor for heavy drinking and problems among adolescents (Beck and Treiman, 1996; Perkins and Craig, 2003) and demonstrate that the peer norm-drinking association is strong among at-risk youths. Low perceived peer norms about drinking, despite mental health status, were associated with fewer alcohol-related consequences. This finding gives continued credence to the idea that individuals with lower perceived norms drink less and experience fewer alcohol-related problems, which has implications for interventions aimed at reducing these perceptions. If perceived norms can be reduced through intervention, drinking and consequences may therefore decrease. Previous work with adolescents (Brown, 2001; D’Amico et al., 2012; Haines et al., 2003; Hansen and Graham, 1991) and college students demonstrates the efficacy of norms interventions (Cronce and Larimer, 2011; Walters and Neighbors, 2005).

Findings from this study also provide new information on the link between mental health and drinking. Specifically, we found that better mental health in combination with high peer norms about drinking led to more negative consequences from alcohol use. One reason for this may be that the alcohol consequences assessed in this study were mostly social-related consequences (e.g., got into a fight, embarrassed oneself) that may occur in social drinking situations. Youths with more depressive or anxiety symptoms may be less likely to experience these social drinking consequences because they are less likely to be in these types of social drinking situations and are more likely to isolate themselves socially. For example, adolescents who drink in public settings are less likely to report poor self-esteem and stress compared with those who drink alone at home (Engels et al., 1999). Youths who are happy, less anxious, and less depressed are more likely to be in social situations (Crowe et al., 1998; Goodman et al., 2001; Hsu and Reid, 2012; La Greca and Harrison, 2005) where they can observe behavior, form perceptions about how their peers are behaving, and potentially experience consequences. This process of social learning is inherent in the creation of perceived norms but may also contribute to increased risk.

Our findings are consistent with research on social anxiety and perceived norms among college students, showing that students with lower reported social anxiety who also reported higher perceived peer drinking norms were most at risk for alcohol-related consequences (Buckner et al., 2011). These findings are important because many interventions are devoted to those with substance use concerns and comorbid mental health problems, and these results suggest that, among adolescents, it is important to continue intervening with youths who experience limited depressive and anxiety symptoms.

In addition, it is important to discuss the sample used in the present study, as there is a substantial amount of research on coping-related drinking among youths who report mental health symptomatology (Najt et al., 2011). However, that research is typically focused on diagnosed depression and/or anxiety, uses samples within treatment centers, and does not discuss more moderate levels of symptomatology. For example, Chan and colleagues (2008) documented high comorbidity rates between self-reported substance dependence and mental health diagnoses among teenagers in treatment for substance use concerns. Our sample of youths receiving a first-time offense was determined by the teen court system in California to not warrant further treatment for substance use disorders and/or mental health disorders, presumably because they were not severe enough in either area. Thus, these teenagers may have reported better mental health than teenagers who may have been referred for further treatment.

Still, it is important to note that this population is at risk for further delinquent behavior, violence, and substance use, making them an important population for research and intervention efforts. Cross-sectional and longitudinal work has suggested that youths who have engaged in delinquent behavior may be particularly at risk for heavy alcohol use and consequences (D’Amico et al., 2008; Mason et al., 2007, 2009). Targeting specific subgroups of adolescents in research studies can provide a better understanding of the connection between moderate levels of mental health symptomatology and alcohol use, both of which may be particularly prominent among youths who have been identified as delinquent (e.g., truancy from school) or who have been implicated in alcohol- or other drug-related offenses.

Limitations

Limitations exist regarding the measures and the sample used. Although we took steps to ensure that participants understood the confidential nature of their self-reported responses regarding illegal behaviors (e.g., underage alcohol use) and that data were separated from the court records, these findings are limited by self-report data. Limitations related to self-report data are well known although possibly exaggerated (Chan, 2009; Conway and Lance, 2010). Typically, self-reported alcohol and other drug use among youths is valid when procedures such as those used in the current study are implemented (e.g., obtaining a Certificate of Confidentiality, discussing confidentiality with youths, research staff [not court staff] collecting all information; e.g., Harrison et al., 2007; Winters et al., 1990).

For the perceived peer norms about drinking question, participants were asked about “a typical teen your age,” which may have been a vague category for some participants. Future research should explore differences when assessing norms for more specific groups (e.g., one’s lighter drinking friends vs. heavier drinking peers in other groups; average peers within one’s network vs. close friends), as individuals may have differential perceptions based on the particular social group to which they belong (Verkooijen et al., 2007).

Additionally, our sample may differ from general adolescent samples in terms of drinking behavior, mental health, and normative perceptions because they were a relatively specialized heavier drinking group. They received an offense for primarily either drinking and/or marijuana use, which typically occurred in a social setting (e.g., drinking or using marijuana in public). This was not a clinical sample, and we did not examine diagnosed mental disorders. Therefore, findings might differ for adolescents diagnosed with a depressive and/or an anxiety disorder. Results also could vary if we assessed the sample over a longer follow-up period. Longitudinal evidence has suggested that the association between alcohol use and poor mental health may be unidirectional, such that heavy alcohol use in adolescence may lead to depression later in adulthood (Fergusson and Horwood, 1999). This group of at-risk youths may continue drinking heavily and develop more severe depression and anxiety symptoms over time, at which point we may see a different association between mental health and substance use. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess perceived drinking norms and mental health status from adolescence into young adulthood.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that at-risk youths who reported better mental health and higher perceived peer norms about drinking also reported more alcohol-related consequences. These findings further our understanding of the association between mental health and alcohol use among adolescents and highlight the importance of perceived peer norms about drinking in influencing consequences from alcohol use. Results support previous research emphasizing the importance of perceptions about peer behavior in adolescent alcohol use and provide further information on how norms may work among at-risk youths with varied levels of mental health symptoms. Targeting these perceptions through intervention can continue to be an efficacious strategy to intervene with at-risk youths.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse for collaborating with us on this project. We also thank Emily Cansler and Megan Zander-Cotugno for their oversight of data collection.

Footnotes

This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01DA019938 (to Elizabeth J. D’Amico).

References

- Akers R L, Krohn M D, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M. Social learning and deviant behavior: A specific test of a general theory. American Sociological Review. 1979;44:636–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria A M, Dohey M A, Mezzich A C, Bukstein O G, Van Thiel D H. Self-reported health problems and physical symptomatology in adolescent alcohol abusers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;16:226–231. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00066-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck K H, Treiman K A. The relationship of social context of drinking, perceived social norms, and parental influence to various drinking patterns of adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:633–644. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick D M, Murphy J M, Goldman P A, Ware J E, Jr, Barsky A J, Weinstein M C. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care. 1991;29:169–176. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B B, Bakken J P, Ameringer S W, Mahon S D. A comprehensive conceptualization of the peer influence process in adolescence. In: Prinstein M J, Dodge K A, editors. Duke Series in child development and public policy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S A. Facilitating change for adolescent alcohol problems: A multiple options approach. In: Wagner E F, Waldron H B, editors. Innovations in adolescent substance abuse intervention. Oxford, England: Elsevier Science; 2001. pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner J D, Ecker A H, Proctor S L. Social anxiety and alcohol problems: The roles of perceived descriptive and injunctive peer norms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:631–638. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In: Lance C E, Vandenberg R J, editors. Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. pp. 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chan Y F, Dennis M L, Funk R R. Prevalence and comorbidity of major internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen B A, Goldman M S, Inn A. Development of alcohol-related expectancies in adolescents: Separating pharmacological from social-learning influences. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:336–344. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D B, Pollock N, Bukstein O G, Mezzich A C, Bromberger J T, Donovan J E. Gender and comorbid psychopathology in adolescents with alcohol dependence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:1195–1203. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J M, Lance C E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2010;25:325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Cronce J M, Larimer M E. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research & Health. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe P A, Philbin J, Richards M H, Crawford I. Adolescent alcohol involvement and the experience of social environments. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1998;8:403–422. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E J, Edelen M O, Miles J N V, Morral A R. The longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among high-risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E J, Ellickson P L, Collins R L, Martino S, Klein D J. Processes linking adolescent problems to substance-use problems in late young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:766–775. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E J, Hunter S B, Miles J N V, Ewing B A, Osilla K C. A randomized controlled trial of a group Motivational Interviewing intervention for adolescents with a first time alcohol or drug offense. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.06.005. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico E J, Tucker J S, Miles J N V, Zhou A J, Shih R A, Green H D J., Jr Preventing alcohol use with a voluntary after-school program for middle school students: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of CHOICE. Prevention Science. 2012;13:415–425. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson P L, Tucker J S, Klein D J. Sex differences in predictors of adolescent smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2001;20:186–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels R C M E, Knibbe R A, Drop M J. Why do late adolescents drink at home? A study on psychological well-being, social integration and drinking context. Addiction Research & Theory. 1999;7:31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D M, Horwood L J. Prospective childhood predictors of deviant peer affiliations in adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1999;40:581–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D M, Lynskey M T. Alcohol misuse and adolescent sexual behaviors and risk taking. Pediatrics. 1996;98:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming C B, Mason W A, Mazza J J, Abbott R D, Catalano R F. Latent growth modeling of the relationship between depressive symptoms and substance use during adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:186–197. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner I M, Larimer M E, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Adler N E, Kawachi I, Frazier A L, Huang B, Colditz G A. Adolescents’ perceptions of social status: Development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):e31. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e31. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/108/2/e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines M P, Barker G P, Rice R. Using social norms to reduce alcohol and tobacco use in two midwestern high schools. In: Perkins H W, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen W B, Graham J W. Preventing alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among adolescents: Peer pressure resistance training versus establishing conservative norms. Preventive Medicine. 1991;20:414–430. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison L D, Martin S S, Enev T, Harrington D. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2007. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population (DHHS Publication No. SMA 07–4249, Methodology Series M-7) [Google Scholar]

- Hill K G, White H R, Chung I J, Hawkins J D, Catalano R F. Early adult outcomes of adolescent binge drinking: Person- and variable-centered analyses of binge drinking trajectories. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:892–901. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooshmand S, Willoughby T, Good M. Does the direction of effects in the association between depressive symptoms and health-risk behaviors differ by behavior? A longitudinal study across the high school years. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C L, Reid L D. Denver, CO: Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association; 2012, August. Social status, binge drinking, and social satisfaction among college students. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L D, O’Malley P M, Bachman J G, Schulenberg J E. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D B, Johnson J G, Bird H R, Weissman M M, Goodman S H, Lahey B B, Schwab-Stone M E. Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: findings from the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:693–699. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian E J. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopf D, Park M J, Paul Mulye T. San Francisco: University of California; 2008. The mental health of adolescents: A national profile, 2008. San Francisco, CA: National Adolescent Health Information Center. Retrieved from http://nahic.ucsf.edu/downloads/MentalHealthBrief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J W, Hummer J F, Neighbors C. Self-consciousness moderates the relationship between perceived norms and drinking in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1529–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca A M, Harrison H M. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W A, Hitch J E, Spoth R L. Longitudinal relations among negative affect, substance use, and peer deviance during the transition from middle to late adolescence. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44:1142–1159. doi: 10.1080/10826080802495211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W A, Hitchings J E, McMahon R J, Spoth R L. A test of three alternative hypotheses regarding the effects of early delinquency on adolescent psychosocial functioning and substance involvement. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:831–843. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: A systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Medicine. 2011;8(2):e1000413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413. Retrieved from http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie M, Jorm A F, Romaniuk H, Olsson C A, Patton G C. Association of adolescent symptoms of depression and anxiety with alcohol use disorders in young adulthood: Findings from the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study. Medical Journal of Australia. 2011;195:S27–S30. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W R, Rollnick S. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. [Google Scholar]

- Najt P, Fusar-Poli P, Brambilla P. Co-occurring mental and substance abuse disorders: A review on the potential predictors and clinical outcomes. Psychiatry Research. 2011;186:159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham B L. Gender differences in trajectories of depressive symptomatology and substance use during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1166–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Fossos N, Woods B A, Fabiano P, Sledge M, Frost D. Social anxiety as a moderator of the relationship between perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:91–96. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hill K G, Hawkins J D, Guo J, Catalano R F, Abbott R D. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:204–212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olds R S, Thombs D L, Tomasek J R. Relations between normative beliefs and initiation intentions toward cigarette, alcohol and marijuana. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:75. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.09.020. e7–75.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page R M, Hammermeister J, Roland M. Are high school students accurate or clueless in estimating substance use among peers? Adolescence. 2002;37:567–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins H W, Craig D W. The imaginary lives of peers: Patterns of substance use and misperceptions of norms among secondary school students. In: Perkins H W, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis I L, Gonzalez G, Rosenheck R, Krystal J H. Comorbidity of alcoholism and psychiatric disorders: An overview. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf H J, Meyer C, Hapke U, John U. Screening for mental health: Validity of the MHI-5 using DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders as gold standard. Psychiatry Research. 2001;105:243–253. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandheim A, Holmen T L, Coombes L, Bentzen N. Alcohol intoxication and mental health among adolescents—a population review of 8983 young people, 13–19 years in North-Trøndelag, Norway: The Young-HUNT Study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2009;3(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-18. Retrieved from http://www.capmh.com/content/3/1/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: Author; 2011. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings (NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. [SMA] 11–4658) [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian T, Jaycox L H, Paddock S M, Chandra A, Meredith L S, Burnam M A. Improving treatment seeking among adolescents with depression: Understanding readiness for treatment. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen M-J, Jansen M, van Gestel A. Are mental health and binge drinking associated in Dutch adolescents? Cross-sectional public health study. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4(1):100. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-100. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1756-0500/4/100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J S, Ellickson P L, Orlando M, Martino S C, Klein D J. Substance use trajectories from early adolescence to emerging adulthood: A comparison of smoking, binge drinking, and marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35:307–332. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J S, Orlando M, Ellickson P L. Patterns and correlates of binge drinking trajectories from early adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychology. 2003;22:79–87. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkooijen K T, de Vries N K, Nielsen G A. Youth crowds and substance use: The impact of perceived group norm and multiple group identification. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:55–61. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters S T, Neighbors C. Feedback interventions for college alcohol misuse: What, why and for whom? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1168–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman E R. Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WestEd. California Healthy Kids Survey. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.wested.org/cs/chks/view/chks_s/17?x-layout=surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Winters K C, Stinchfield R D, Henly G A, Schwartz R H. Validity of adolescent self-report of alcohol and other drug involvement. Substance Use & Misuse. 1990;25(s11):1379–1395. doi: 10.3109/10826089009068469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki S, Fukuhara S, Green J. Usefulness of five-item and three-item Mental Health Inventories to screen for depressive symptoms in the general population of Japan. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2005;3(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-48. Retrieved from http://www.hqlo.com/content/3/1/48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]