Abstract

Objective:

Pregaming (drinking before a social occasion) predicts alcohol consequences between persons; people who pregame report greater consequences than those who do not. The present study examined within-person associations between pregaming and daily consequences.

Method:

Participants were college students (N = 44; 50% female) reporting past-month pregaming. Daily drinks consumed (during pregaming and across the entire drinking episode) and alcohol consequences were assessed with a 30-day Timeline Followback interview.

Results:

Within individuals, engaging in pregaming predicted consequences experienced on a given day above and beyond the number of drinks consumed across the drinking episode and typical drinking level. Furthermore, there was a trend toward pregaming placing women at more risk for consequences than men.

Conclusions:

Findings support a context-specific risk for consequences that is conferred by pregaming and that is independent of how much drinking occurs across the drinking episode. Results highlight pregaming as a target for future interventions.

Heavy drinking and associated alcohol-related consequences among college students continue to present a public health concern (Hingson et al., 2005, 2009). Therefore, examinations of specific contexts or drinking behaviors that are associated with alcohol-related consequences are needed. Such work may serve to identify those students most in need of interventions and may help uncover important intervention targets. One specific drinking behavior that has been a recent focus of the literature is pregaming. Pregaming, also referred to as prepartying or preloading, is a pervasive and risky drinking practice among college students that commonly involves drinking large quantities of alcohol in a compressed period before a planned social occasion (DeJong et al., 2010). The current research on pregaming, albeit limited, indicates that this drinking practice places students at risk for experiencing more alcohol-related consequences (Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007; Read et al., 2010). In the present study, we extend this literature by using daily data analyzed with hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) to examine whether, within persons, pregaming (the practice of consuming alcohol before going out for the night or before a function has started) is associated with subsequent alcohol-related consequences at the daily level, above and beyond (a) the amount of drinking across the drinking day and (b) between-person influences of typical drinking behavior. We also examined whether the association between pregaming and consequences at the daily level differs by gender.

Associations between pregaming and consequences

Across a handful of studies, pregaming has been shown to predict alcohol-related problems broadly. Individuals who report any pregaming also report higher levels of alcohol consequences (Paves et al., 2012; Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007; Read et al., 2010), and the past-month total number of drinks consumed during pregaming is associated with consequences (Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007; Pedersen et al., 2009). Another study found that an index of past-month quantity by frequency of pregaming was cross-sectionally linked to alcohol-related problems but only when typical drinking behavior (past-month Quantity × Frequency) was not controlled for (Merrill et al., 2010). Thus, in between-person analyses, associations between pregaming and consequences may be attributable to the generally heavier drinking tendencies of students who engage in pregaming. Although findings from these studies are important, each is limited by examination only of broad-based (i.e., between-person) associations between pregaming and consequences.

To our knowledge, there has been only one other examination of the effects of pregaming on alcohol-related consequences at the event level (LaBrie and Pedersen, 2008). That study compared two drinking days within persons—the most recent ones on which pregaming did and did not occur. Students experienced significantly more consequences on their pregaming day. However, because only two drinking days were included in the analyses, the reliability and generalizability of the findings may be limited. In addition, it is unclear whether the increase in consequences on the pregaming day that was observed in that study was a function of pregaming specifically or of the total number of drinks consumed across the drinking episode. In the present study, we extended this work by using multilevel models to examine within-day associations between pregaming and consequences experienced, after controlling for both total number of drinks consumed across the drinking day and typical drinking patterns.

Gender differences influencing pregaming, alcohol consequences, and their association

Gender differences have been noted across multiple domains of alcohol involvement. Data clearly indicate that men are more likely than women to drink heavily (Johnston et al., 2003; O’Malley and Johnston, 2002). Some studies have found that men experience more alcohol consequences than women do (Carlucci et al., 1993), whereas others have not (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004; Perkins, 2002; White et al., 2002). Specific to pregaming, men consume more drinks than women do on days when pregaming occurs (LaBrie and Pedersen, 2008; Read et al., 2010), but do not report more consequences (LaBrie and Pedersen, 2008). The absence of gender differences in consequences in studies conducted in both the general drinking and pregaming-specific literature may be attributable to gender differences in the metabolism of alcohol. Even though men drink more, women may become similarly or even more intoxicated (Carey et al., 2004; Hustad and Carey, 2005).

In the non-pregaming drinking literature, it has been shown that the association between alcohol use and consequences is stronger for women than for men (Harrington et al., 1997). At equal levels of consumption, women may experience more negative consequences associated with risk for personal harm (e.g., blackouts, passing out, injury) and dependence symptoms (e.g., tolerance, inability to limit drinking; Sugarman et al., 2009). A question yet unanswered is whether or not the association between pregaming behavior and alcohol consequences at the daily level differs by gender (i.e., whether women and men are equally likely to report consequences as a function of pregaming). Some studies in the pregaming literature show that pregaming behavior does not have a differential impact on the experience of overall alcohol-related consequences for male and female students (LaBrie and Pedersen, 2008; Pedersen et al., 2009). Yet, findings may differ when looking at within-day associations; it is possible that women are more at risk for consequences as a function of engaging in pregaming, given the higher levels of intoxication that they may achieve when they engage in pregaming (Read et al., 2010).

Gaps in the literature

Much of the work on pregaming conducted to date has been cross-sectional and descriptive in nature (Borsari et al., 2007; Paves et al., 2012; Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007; Read et al., 2010). Studies examining associations between pregaming and alcohol-related consequences have relied largely on retrospective, single-item self-report measures to assess typical pregaming behavior, which does not allow for more fine-grained examinations of behavioral patterns possible with daily data. Such studies examining whether pregaming is associated with alcohol consequences over a prior period (past month: Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007; Pedersen et al., 2009; past year: Read et al., 2010) cannot reveal much about the risk conferred by a single pregaming episode and/or determine whether in fact pregaming itself, and not simply the amount of alcohol consumed across the drinking episode, increases risk. Prior work also has failed to ascertain whether there are unique effects of pregaming that are different from the fact that those who pregame tend to be heavier drinkers and therefore are at greater risk for consequences. Finally, to our knowledge, no study has examined whether daily associations between pregaming behavior and alcohol-related consequences differ by gender.

Present study

To address the above-noted gaps, we examined a sample of 44 college students who reported past-month pregaming, using daily data collected with an adaptation of the Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1992). Multilevel modeling was used to test whether consequences at the daily level were uniquely a function of pregaming behavior or of the drinking that occurs across the entire drinking episode, and when typical drinking levels are controlled for. Determining whether pregaming places students at risk for more consequences will inform whether this particular drinking behavior is one that may need to be targeted more directly in intervention. We hypothesized that pregaming on a given day would be significantly associated with consequences above and beyond total number of drinks consumed across the drinking day (within-person) and typical drinking across the 30 days (between-person). A secondary hypothesis was that the association between pregaming and consequences would be stronger for women.

Method

Participants and procedure

All study procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board. Participants for the present study were a subset of undergraduate students (N = 44; 50% female) recruited from public and private universities in the northeastern United States for a larger study on implicit alcohol cognitions in students with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Recruitment was ongoing and was fairly equally spaced across the year (including winter and summer breaks) from February 2009 to January 2010. For the larger study, inclusion criteria required that eligible students be ages 18–24 years, native English speakers, enrolled full time as undergraduates at a 4-year university, and without hearing impairments or color blindness. Participants also had to report drinking alcohol at least once/month during the 3 months prior to participation. Students were recruited and identified for initial eligibility through an undergraduate research pool and through advertisements. For the present study, we used data only from participants who reported pregaming at least once over the past month. Ethnicity was reported as follows: 70.5% White, 6.8% African American, 4.5% Asian, 2.3% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 11.3% other/multiracial. Eleven percent identified themselves as Hispanic, and two participants did not report ethnicity (4.5%). Our sample consisted of 43.2% freshmen; the average age was 19.66 years (SD = 1.74).

Based on responses to an initial eligibility screen, students were invited to participate in the first part of the study. They completed brief self-report questionnaires including demographic information, and an interview to determine trauma and posttraumatic stress status for the purposes of the larger study. This assessment session lasted approximately 2 hours, and all students received either course credit or $20.

Eligible individuals were invited to participate in the second session of the study, which took place 1–4 weeks later. At this session, participants provided informed consent and then completed several questionnaires on alcohol-related behaviors and an experimental task assessing implicit alcohol cognitions (modified Stroop). Of relevance to the present study, following experimental tasks, participants also took part in a past-90-day TLFB interview assessing alcohol use; consequences were assessed for the past 30 days during the interview. This session took approximately 2.5 hours to complete, and students received either $30 or course credits.

Measures

Demographics.

A range of demographic factors (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity, school year) was assessed.

Alcohol use and pregaming: Timeline Followback.

The TLFB interview (Sobell and Sobell, 1992) was used to assess both pregaming behavior and general alcohol use. The TLFB interview is a calendar-assisted interview that provides a way to cue memory and enhance accurate recall. For the present study, the past 30 days was the period of analysis, as this is the period for which daily alcohol consequences also were assessed (see below). Before the interview, a standard drink was defined for participants (12 oz. of beer, 5 oz. of wine, 1.5 oz. of distilled spirits). For each day, participants were asked to report the number of drinks and the number of hours over which these drinks were consumed. Pregaming was defined for participants as “the practice of consuming alcohol before going out for the night or before a function started.” On days when pregaming was endorsed, drinks and hours were assessed separately for pregaming and after pregaming (during the main social event) episodes. For descriptive purposes, data from the TLFB also were summarized across the most recent month to yield alcohol consumption descriptive information (see Results).

Data from the TLFB also allowed us to calculate estimated blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) for each participant on each day of drinking. We used the equation [(c/2) × (GC/w)] – (.02 × t), where c = total number of standard drinks consumed, GC = gender constant (9.0 for women, 7.5 for men), w = weight in pounds, and t = total hours spent drinking (Dimeff et al., 1999; Hustad and Carey, 2005). For descriptive purposes, average BACs on drinking days, pregaming days, and non-pregaming days were calculated.

Alcohol consequences.

As stated above, consequences also were assessed during the 30-day TLFB. The TLFB has been used in other studies to assess the occurrence of behaviors other than just alcohol use (e.g., sexual risk behavior: Carey et al., 2001; victimization: Parks and Fals-Stewart, 2004). Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced any of 24 alcohol-related consequences on each drinking day, using items from the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (B-YAACQ; Kahler et al., 2005). The 24-item B-YAACQ uses a subset of items from the original 48-item YAACQ (Read et al., 2006) that are minimally redundant and that most closely follow a uni-dimensional model (i.e., representing a continuum from less to more severe alcohol consequences in college students) and demonstrate strong psychometric properties (Kahler et al., 2005, 2008). Example items include missed work or classes at school because of drinking, passed out from drinking, and had problems with boyfriend/girlfriend/spouse/parents because of drinking.

Data analytic plan

HLM was used given that data were characterized by multiple assessments nested within persons. HLM allowed us to examine within-person associations (Level 1, whether pregaming confers risk for alcohol consequences at the daily level) while providing natural controls for between-person differences (Level 2, typical drinking, gender) in our outcome variable (daily consequences) (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002).

Data screening and preparation.

First, we screened for missing data. All participants had complete data on Level 2 variables of interest (gender, typical drinking), and the use of an interview minimized missing data at the daily level (Level 1). Across participants, data were missing because of failure to provide information during the interview on alcohol use or consequences on less than .01% of 1,320 potential daily assessments. Next we created a multilevel person-period data set with observations representing the n = 30 potential daily occasions of each Level 1 predictor, control, and outcome nested within the N = 44 persons. This data set was therefore represented by 1,320 person days (1,320 = n × N, or 30 × 44), resulting in adequate power to test effects of interest.

Substantive analyses.

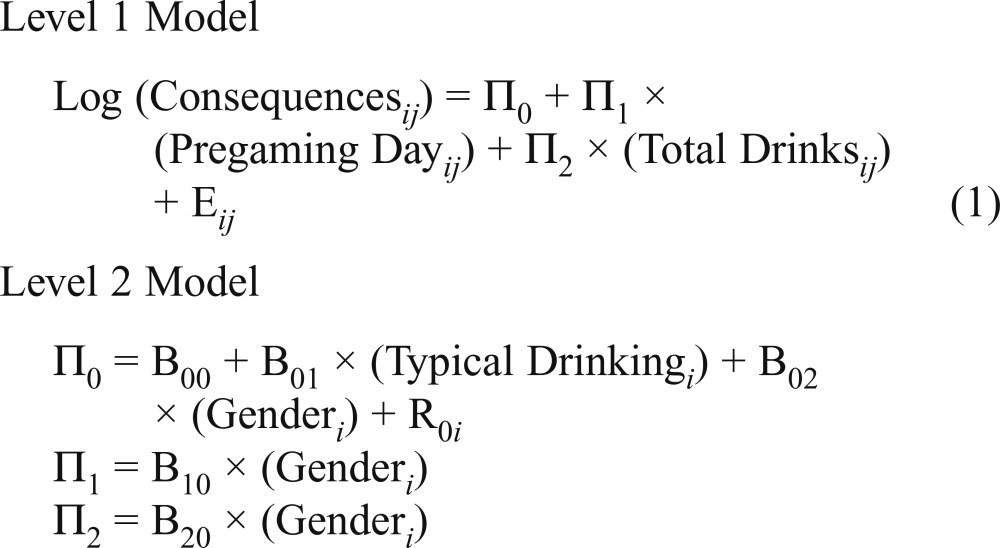

All substantive analyses were conducted with HLM 6.0 (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). Because the outcome variable (number of consequences) was a non-normally distributed count variable, we used an overdispersed Poisson model with a log link, which offers more conservative estimates in the presence of overdispersion (Atkins and Gallop, 2007; Raudenbush et al., 2004). The multilevel equation was estimated as follows:

|

The model shown in Equation 1 tested the following hypotheses:

(1) Within individuals (Level 1), whether one engaged in pregaming (Pregaming Day, coded 0 for non-pregaming and 1 for pregaming) will significantly predict daily alcohol consequences. This effect will be demonstrated above and beyond (a) the number of drinks consumed across the total drinking episode (Total Drinks, regardless of whether those episodes included pregaming) and (b) Typical Drinking (mean number of drinks per drinking day), a between-person (Level 2) effect that will confer risk for higher mean levels of daily consequences.

(2) Gender (Level 2) will moderate the effects of the pregaming day on daily consequences, such that women will show stronger associations between pregaming behavior and consequences experienced.

We also controlled for the potential impact of gender (a) on average number of daily consequences and (b) as a predictor of the slope of total number of drinks on consequences (Total Drinks × Gender interaction), given that some literature (described above) suggests the inclusion of such effects. Typical Drinking at Level 2 was grand mean centered by subtracting the mean across subjects from each participant’s value, such that the intercept represented consequences at average levels of alcohol use. Dichotomous variables (Pregaming Day, Gender) were not centered. Total number of drinks at Level 1 also was not centered because person-centering total drinks would provide a test of whether drinking more drinks than one typically does is associated with higher levels of consequences. However, we were interested only in controlling for the raw number of drinks consumed on that day in the prediction of that day’s consequences. Intercept effects were specified as random, to allow individual differences in mean levels of consequences; slope effects were fixed, as we did not expect variation between participants in the associations between variables of interest and consequences.

We checked for violations of assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality of Level 1 and Level 2 residuals. Plots of residuals were examined for significant outliers or influential cases at the individual level, and plots of residuals versus predictors were examined to identify whether variability differed across predictor level (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). These diagnostic tests resulted in the need for deletion of a single multivariate outlier (from an initial sample of 45 participants). Finally, effect sizes for effects of primary interest were calculated, where r = √(t2/t2 + df) (Rosenthal and Rosnow, 1991), and where effects of r = .1 − .23 are considered small, r = .24 − .36 are medium, and r = .37 or greater are large (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1. Men reported drinking more often, drinking more drinks per occasion, and drinking more during pregaming than women. However, frequency of pregaming, consequences, and BAC did not differ by gender. Across men and women, participants consumed significantly more drinks on pregaming days (M = 9.64, SD = 5.28) than on non-pregaming days (M = 5.26, SD = 2.30), t(41) = 6.29, p < .001. They reached higher levels of intoxication on pregaming days (M =0.17, SD = .08) than on non-pregaming days (M = 0.09, SD = .04), t(41) = 7.21 p < .001. Participants also experienced twice as many consequences (M = 2.43, SD = 2.58) on pregaming as compared with non-pregaming days (M = 1.22, SD = 1.22), t(41) = 3.13, p = .003. Thus, descriptively, pregaming is associated with higher levels of drinking and consequences. Furthermore, men drink more but achieve similar levels of intoxication and experience similar levels of consequences.

Table 1.

Descriptives and gender comparisons on drinking and pregaming behavior

| Overall sample (N = 44) M (SD) | Male (n = 22) M (SD) | Female (n = 22) M (SD) | Gender differences |

|||

| Variable | df | t | p | |||

| Drinking behavior | ||||||

| Past-month drinking days | 8.20 (5.55) | 10.41 (6.26) | 6.00 (3.69) | 42 | 2.85 | .007 |

| Drinks per drinking day | 6.71 (2.52) | 7.75 (2.37) | 5.66 (2.25) | 42 | 3.00 | .005 |

| Past-month total no. of conseq. | 12.48 (12.14) | 14.59 (14.40) | 10.36 (9.23) | 42 | 1.16 | n.s. |

| Past-month no. of different conseq. | 6.52 (4.46) | 7.36 (4.90) | 5.68 (3.90) | 42 | 1.26 | n.s. |

| Conseq. per drinking day | 1.56 (1.20) | 1.47 (1.24) | 1.65 (1.18) | 42 | -0.50 | n.s. |

| Typical BAC | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.12 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.06) | 42 | -0.42 | n.s. |

| Pregaming behavior | ||||||

| Past-month pregaming days | 2.75 (2.11) | 3.09 (2.25) | 2.41 (1.97) | 42 | 1.07 | n.s. |

| Drinks per pregaming episode | 4.56 (2.39) | 5.58 (2.38) | 3.54 (1.98) | 42 | 3.08 | .004 |

| Drinks per pregaming day | 9.64 (5.28) | 11.93 (5.79) | 7.21 (3.09) | 42 | 3.37 | .002 |

| Drinks per non-pregaming day | 5.26 (2.30) | 6.24 (2.28) | 4.28 (1.92) | 40 | 3.01 | .004 |

| Conseq. per pregaming day | 2.43 (2.58) | 2.42 (2.92) | 2.44 (2.26) | 42 | -0.03 | n.s. |

| Conseq. per non-pregaming day | 1.22 (1.22) | 1.23 (1.45) | 1.21 (0.99) | 42 | 0.06 | n.s. |

| BAC on pregaming day | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.18 (0.08) | 0.17 (0.09) | 42 | 0.45 | n.s. |

| BAC on non-pregaming day | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) | 40 | 0.27 | n.s. |

Notes: n.s. = not significant; conseq. = consequences; BAC = blood alcohol concentration.

Across the 1,320 person-days, 121 drinking days were characterized by pregaming and 240 were not. Thus, one third of all drinking days involved pregaming. We examined the frequency of endorsement of each consequence item (i.e., the number of occasions it occurred across the 30 days among the 44 participants) as well as the percentage of all pregaming days and non-pregaming days on which each consequence occurred. Across all consequence items, the percentage of pregaming days on which the consequence occurred was higher than the percentage of non-pregaming days on which it occurred. The most frequently endorsed consequence items included had less energy or felt tired because of drinking (n = 66 occasions; occurred on 32% of pregaming days vs. 13% of non-pregaming days), hangover (n = 55; 26% pregaming vs. 10% non-pregaming), difficulty limiting one’s drinking (n = 39; 17% pregaming vs. 8% non-pregaming), said or did embarrassing things (n = 36; 19% pregaming vs. 5% non-pregaming), felt sick/vomited (n = 33; 12% vs. 8%), did impulsive things (n = 33; 10% vs. 5%), took foolish risks (n = 32; 12% vs. 8%), and blacked out (n = 30; 17% vs. 5%).

Substantive analysis

Full model results are presented in Table 2. Hypothesis 1 was supported. That is, the effect of pregaming day at Level 1 was significant (B = 1.1 7, p < .001). Pregaming on a given day conferred risk for consequences, above and beyond number of drinks consumed across the entire drinking episode (total drinks: B = 0.20, p < .001) at Level 1 and above and beyond the non-significant between-person (Level 2) effects of typical drinks per drinking day (typical drinking) and gender. Effect sizes for pregaming day and total number of drinks were small (r = .17) and medium (r = .46), respectively.

Table 2.

Multilevel model results: Testing pregaming as a predictor of daily consequences

| Fixed effects (predictors) | B (SE) | SE | t | df | p |

| Intercept | -1.98 | 0.18 | -11.18 | 42 | <.001 |

| Typical drinking | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 42 | .65 |

| Gender | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 42 | .72 |

| Pregaming day | 1.17 | 0.17 | 6.88 | 1338 | <.001 |

| Pregaming Day × Gender | -0.40 | 0.21 | -1.88 | 1338 | .06 |

| Total drinks | 0.20 | 0.01 | 14.74 | 1338 | <.001 |

| Total Drinks × Gender | -0.07 | 0.01 | -4.87 | 1338 | <.001 |

Notes: Pregaming day: 0 = non-pregaming day, 1 = pregaming day. Total drinks = total number of drinks consumed across the drinking episode. Gender: 0 = female, 1 = male. Typical drinking = mean number of drinks per drinking day (across the 30-day assessment).

Also shown in Equation 1, at Level 2, gender was included as a predictor of the slopes of pregaming day and total number of drinks. This essentially tests two cross-level interaction effects (Pregaming Day × Gender; Total Drinks × Gender), allowing examination of whether the effects of pregaming day and total number of drinks on consequences differ between men and women. We observed a significant Total Drinks × Gender interaction (B = -0.07, p < .001); number of drinks consumed across the drinking episode was more strongly associated with consequences for women than for men. Regarding Hypothesis 2, we observed a marginally significant Pregaming Day × Gender interaction (B = -0.40, p = .06); there was a trend toward a stronger association between pregaming and number of consequences for women. The size of this effect was small (r = .07).

To further understand the significant gender differences in the effect of total number of drinks but not pregaming on consequences at the daily level, we ran an exploratory model substituting daily and typical BACs for daily and typical number of drinks. In this model, gender did not moderate the slope of daily BAC on consequences (p > .05). That is, at similar BACs, men and women experience similar levels of consequences. In this model, pregaming day still significantly predicted consequences (B = 1.28, p < .001), and this effect was significantly moderated by gender (B = -0.71, p = .005) such that women experienced more consequences when they pregamed, when the level of intoxication was controlled for. Thus, pregaming behavior is associated with consequences above and beyond not only number of drinks but also the BAC one reaches that day and more typically. When BAC rather than number of drinks is controlled for, pregaming is more strongly associated with consequences for women.

Discussion

In the present study, daily data support an important context-specific association between pregaming and deleterious drinking outcomes, and point to a risk conferred by pregaming irrespective of how much alcohol is consumed during the drinking episode. Consistent with our hypotheses, pregaming significantly predicted an increase in the number of alcohol-related consequences experienced at the daily level (i.e., that night/day). Importantly, this finding held true even when we took into account the number of drinks consumed across the entire drinking episode (or BAC reached) and typical drinking levels (or typical BAC).

There are several explanations for why drinking during a specific pregaming episode may be uniquely associated with greater consequences. For one, this may be because of the way in which students are drinking while pregaming (Wells et al., 2009). Pregaming often takes place in contexts with minimal restraints (i.e., at home vs. at a bar), which may result in consumption of large amounts of alcohol. In addition, these large amounts of alcohol often are consumed in a short period during pregaming (Read et al., 2010), and faster rates of alcohol consumption may put students at greater risk for blackouts in particular (Perry et al., 2006) and, therefore, perhaps for other consequences as well. Moreover, recent research suggests that one of the top reasons students cite for pregaming is “to get buzzed before going to the event” (Bachrach et al., 2012). Thus, it may be that the specific intention of getting drunk during pregaming is what accounts for the association between this behavior and consequences. Furthermore, pregaming may result in decrements in self-regulation, leading to further heavy drinking during the subsequent social event (Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007). It may not just be the pregaming, but the continued drinking that occurs later in the night, that places students at risk. In addition, pregaming may place students at risk for specific types of problems, including blackouts, risky behaviors (e.g., drunk driving), social/interpersonal problems (e.g., arguments), and academic/occupational problems (e.g., missing class the following morning) (Merrill et al., 2010). Pregaming also may increase rates of consequences associated with driving or walking to the next destination (e.g., driving while intoxicated, impaired judgment regarding personal safety) (Read et al., 2010). Future research should examine the mechanisms involved in the pregaming-consequence links demonstrated in this study.

In the present study, we also observed a marginal gender difference in the extent to which pregaming behavior predicted same-day consequences when the number of drinks consumed across the drinking episode was controlled for. There was a trend toward women being more likely to experience consequences as a function of pregaming. This trend may be because women achieve similar or higher levels of intoxication at a lower number of drinks than do men both generally (Carey et al., 2004; Hustad and Carey, 2005) and during pregaming (Read et al., 2010). In the present study, even though men drank more than women did, women reached similar BACs as men, perhaps placing them at similar or higher risk for consequences. Furthermore, in our exploratory model that controlled for BAC instead of drinks, the interaction between pregaming and gender was significant. That is, when they do reach BACs equivalent to men’s, women are clearly at greater risk for consequences as a function of pregaming.

Although not of central interest to the present study, gender also was examined as a predictor of average daily consequences and as a moderator of the association between total number of drinks and consequences at the daily level. Whereas t tests indicated differences in alcohol use between men and women, our multivariate hierarchical linear models did not reveal differences in average number of daily consequences by gender. Yet, gender did moderate the effect of total number of drinks consumed on consequences experienced at the daily level; these variables were more strongly associated for women. This is consistent with prior research demonstrating stronger correlations between alcohol use and consequences for women (Harrington et al., 1997). However, in an exploratory model substituting BAC for number of drinks, gender did not moderate the slope of daily BAC on consequences. That is, at similar BACs, men and women experience similar levels of consequences as a function of level of intoxication.

Event-level analysis of the pregaming-consequence link is a significant strength of the present study. Our method of using the TLFB to collect daily data to be analyzed with HLM allowed for identification of associations between a specific pregaming episode and outcomes related to that episode. Interestingly, when both day-to-day within-person variability in total alcohol use and between-person variability in average use across time (typical use) were modeled, only daily-level associations emerged between alcohol use and consequences. The drinking that occurs during specific drinking events (i.e., alcohol consumption at the daily level)—rather than heavy drinking in general—is what contributes most to the risk of negative consequences on a given day. Importantly, pregaming was a significant predictor of consequences above and beyond both within- and between-person effects of drinks per occasion or typical BAC.

Clinical implications

Given the clear association between pregaming behavior and consequences in the present study, pregaming is a risk behavior that may deserve particular attention in prevention and intervention efforts on college campuses. In terms of prevention, many colleges already provide alcohol education at matriculation (Hustad et al., 2010; Lovecchio et al., 2010). Education on the specific risk posed by pregaming may be rolled into such efforts. To reduce the prevalence of pregaming, campuses might also benefit from the use of breath test devices at campus functions, along with requirements that students not be permitted to attend such functions if intoxicated (Borsari et al., 2007). Regarding intervention, personalized feedback interventions (Lewis et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2010) might benefit from assessment and incorporation of feedback on pregaming behavior and its risks in particular. Finally, students who report pregaming, and women in particular, may need to be prioritized for interventions, given that they may be those most at risk for deleterious outcomes.

Limitations and future directions

The present study has limitations. Some research suggests that pregaming may place students at risk for certain types of consequences but not others (Merrill et al., 2010). Although our sample size (N = 44, 1,320 person-days) was adequate to test the hypotheses of the present study, this sample size combined with relatively low frequency of any given consequence item prevented us from being able to examine multilevel models predicting unique types of alcohol consequences. However, descriptive analyses did point to an increased likelihood of unique consequence types on days during which pregaming took place.

Second, although levels of alcohol use and consequences in our sample were comparable to those in other, larger samples of pregamers in particular (Bachrach et al., 2012; Pedersen and LaBrie, 2007; Pedersen et al., 2009; Read et al., 2010), findings from this relatively small sample may not generalize to college drinkers who do not pregame, and future examinations of other samples of pregamers with different ethnic compositions and from different campus types are warranted. Additional research with larger samples and/ or longer periods also would allow examination of links between pregaming and specific consequences as well as of potential gender differences in such links.

Third, although the present study is a step forward from prior work in that we examined event-level links between pregaming behavior and consequences, we were unable to examine whether pregaming places students at risk for increased consequences over the course of time. Again, longer assessment periods would help to answer this question.

Fourth, the TLFB method relies on retrospective recall. Although the TLFB shows strong concurrent validity with daily diary and other prospective methods in the assessment of alcohol use in college students (Bernhardt et al., 2009), it has not been used previously for the assessment of consequences. The use of even more fine-grained methodology (e.g., ecological momentary assessment; Shiffman, 2009) to examine the link between pregaming and consequences as they occur contemporaneously is an exciting direction for future research.

As discussed above, another important question that remains is precisely why pregaming confers risk of increased consequences. Several potential explanations were outlined above and should be tested in future research. Furthermore, moderators of the effect of pregaming on consequences, other than gender, also should be examined. For example, it seems plausible that certain motives for pregaming (Bachrach et al., 2012) might predict stronger pregaming-consequence associations; individuals engaging in pregaming because they desire high levels of intoxication versus other motives (e.g., to drink preferred alcohol, to feel less anxious) may be those most at risk. A final question left unanswered is whether it is the drinking that takes place during pregaming, after pregaming (during the main social event), or across the drinking episode that is most influential on consequences. Additional research is needed in this area.

Conclusions

The current findings support a context-specific risk for drinking consequences that is conferred by pregaming—a risk that is independent of how much drinking occurs across the entire drinking episode or how much an individual typically drinks. We also found evidence that women are at particular risk for consequences when they engage in pregaming. Our findings highlight several potential avenues for continued research on pregaming and suggest that pregaming provides an important target for prevention and intervention strategies.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant R01AA016564 (to Jennifer P. Read)

References

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach RL, Merrill JE, Bytschkow KM, Read JP. Development and initial validation of a measure of motives for pregaming in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt JM, Usdan S, Mays D, Martin R, Cremeens J, Arriola KJ. Alcohol assessment among college students using wireless mobile technology. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:771–775. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Boyle KE, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Kahler CW. Drinking before drinking: Pregaming and drinking games in mandated students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2694–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Weinhardt LS. Assessing sexual risk behaviour with the Timeline Followback (TLFB) approach: Continued development and psychometric evaluation with psychiatric outpatients. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2001:12,365–375. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Neal DJ, Collins SE. A psychometric analysis of the self-regulation questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci K, Genova J, Rubackin F, Rubackin R, Kayson WA. Effects of sex, religion, and amount of alcohol consumption on self-reported drinking-related problem behaviors. Psychological Reports. 1993;72:983–987. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, DeRicco B, Schneider SK. Pregaming: An exploratory study of strategic drinking by college students in Pennsylvania. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:307–316. doi: 10.1080/07448480903380300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington NG, Brigham NL, Clayton RR. Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1997;47:237–246. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement. 2009;16:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Carey KB. Using calculations to estimate blood alcohol concentrations for naturally occurring drinking episodes: A validity study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2003. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2002. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER. Prepartying promotes heightened risk in the college environment: An event-level report. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:955–959. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: Personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2495–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovecchio CP, Wyatt TM, DeJong W. Reductions in drinking and alcohol-related harms reported by first-year college students taking an online alcohol education course: A randomized trial. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15:805–819. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.514032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Bachrach RL, Bytschkow KM, Dellaccio JM, Read JP. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism. San Antonio, TX: 2010, June. Motivation for pre-gaming and its association with alcohol-related problem types. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Jensen MM, Walter T, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Efficacy of web-based personalized normative feedback: A two-year randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:898–911. doi: 10.1037/a0020766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Fals-Stewart W. The temporal relationship between college women’s alcohol consumption and victimization experiences. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:625–629. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122105.56109.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paves AP, Pedersen ER, Hummer JF, LaBrie JW. Prevalence, social contexts, and risks for prepartying among ethnically diverse college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie J. Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:237–245. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW, Kilmer JR. Before you slip into the night, you’ll want something to drink: Exploring the reasons for prepartying behavior among college student drinkers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:354–363. doi: 10.1080/01612840802422623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Surveying the damage: A review of research on consequences of alcohol misuse in college populations. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 2002;14:91–100. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry PJ, Argo TR, Barnett MJ, Liesveld JL, Liskow B, Hernan JM, Brabson MA. The association of alcohol-induced blackouts and grayouts to blood alcohol concentrations. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2006;51:896–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage: 2002. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, Toit M. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. HLM 6: Hierarchical linear and non-linear modeling. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Bytschkow K. Before the party starts: Risk factors and reasons for “pregaming” in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:461–472. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1991. Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sugarman DE, DeMartini KS, Carey KB. Are women at greater risk? An examination of alcohol-related consequences and gender. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:194–197. doi: 10.1080/10550490902786991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Graham K, Purcell J. Policy implications of the widespread practice of ‘pre-drinking’ or ‘pre-gaming’ before going to public drinking establishments: Are current prevention strategies backfiring? Addiction. 2009;104:4–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Jamieson-Drake DW, Swartzwelder HS. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students: Results of an e-mail survey. Journal of American College Health. 2002;51:117–131. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]