Abstract

Legumes play an important role as food and forage crops in international agriculture especially in developing countries. Legumes have a unique biological process called nitrogen fixation (NF) by which they convert atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia. Although legume genomes have undergone polyploidization, duplication and divergence, NF-related genes, because of their essential functional role for legumes, might have remained conserved. To understand the relationship of divergence and evolutionary processes in legumes, this study analyzes orthologs and paralogs for selected 20 NF-related genes by using comparative genomic approaches in six legumes i.e., Medicago truncatula (Mt), Cicer arietinum, Lotus japonicus, Cajanus cajan (Cc), Phaseolus vulgaris (Pv), and Glycine max (Gm). Subsequently, sequence distances, numbers of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) and non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (Ka) between orthologs and paralogs were calculated and compared across legumes. These analyses suggest the closest relationship between Gm and Cc and the highest distance between Mt and Pv in six legumes. Ks proportional plots clearly showed ancient genome duplication in all legumes, whole genome duplication event in Gm and also speciation pattern in different legumes. This study also reports some interesting observations e.g., no peak at Ks 0.4 in Gm-Gm, location of two independent genes next to each other in Mt and low Ks values for outparalogs for three genes as compared to other 12 genes. In summary, this study underlines the importance of NF-related genes and provides important insights in genome organization and evolutionary aspects of six legume species analyzed.

Keywords: nitrogen fixation, legume, comparative analysis, Ks, evolution

Introduction

Legume is an important class of plants that provides protein in diet for a significant proportion of human population as well as supplies nitrogen to environments. Legumes perform a special symbiotic process called nitrogen fixation (NF) that can fix atmospheric nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) by rhizobium. Papilionoideae subfamily contains majority of commercially important legumes as well as model legume species. Papilionoideae subfamily can be divided into two groups. One is Hologalegina (cool season legumes), including Medicago truncatula (Mt), chickpea (Cicer arietinum, Ca), and Lotus japonicus (Lj), the other is Phaseoloid (warm season legumes), including soybean (Glycine max, Gm), common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris, Pv), and pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan, Cc). In context of understanding biological process of NF, many mutants were developed or identified and NF-related genes were isolated from two model legumes, Mt and Lj (Kouchi et al., 2010). While genome sequencing projects were initiated earlier in Mt (Young et al., 2011) and Lj (Sato et al., 2008), genome sequences have become available for crop legumes like soybean (Schmutz et al., 2010), pigeonpea (Varshney et al., 2012), chickpea (Varshney et al., 2013), common bean (http://phytozome.net). Nevertheless, even before the availability of genome sequences, researchers exploited the BAC sequences to understand not only comparative evolutionary history of a range of genes but also genome duplication and divergence events (Schlueter et al., 2007; Shin et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009). As genome sequences of several legumes have become available in recent years, analysis for speciation and rearrangements is possible in more species.

NF-related genes are very specific and essential to legumes therefore they can be good genomic tools for understanding the process of evolution in legumes. Moreover, morphological differences of nodulation have been used as one of the taxonomic criteria so it is plausible to utilize sequences of NF-related genes for phylogenetic analysis (Sprent, 2000, 2007). After several times of major and minor rearrangements, legumes were diverged into different species (Lavin et al., 2005). Orthologs originate from speciation while paralogs are caused by duplication (Koonin, 2005). It is also important to note that while some genes can be duplicated before speciation and some after speciation. To avoid confusion of such genes with orthologs and paralogs, duplicated genes before speciation are called outparalogs and after speciation are called inparalogs (Koonin, 2005).

Relative timing of duplication of two homologs for a given gene between two species can be estimated by numbers of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) value (Koch et al., 2000; Blanc and Wolfe, 2004; Shoemaker et al., 2006). Lower Ks value suggests that divergence between these homologs happened recently. The ratio of number of non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (Ka) and Ks (Ka/Ks) provides information of the selection pressure in sequence evolution (Hurst, 2002).

In view of the above, this article presents analysis and critical appraisal on 20 NF-related genes for understanding gene-level evolution in six legume species (Ca, Cc, Gm, Lj, Mt, and Pv) by using comparative genomics approaches.

Materials and methods

Gene compilation and sources of sequence data

A list of 52 NF-related genes was utilized from Gm genome sequence data (Schmutz et al., 2010). Gene names were taken from gene cloning publications of Mt or Gm and gene sequences were downloaded from NCBI website. Coding DNA sequences (CDS) of six legumes were downloaded for finding homologs by BLAST from Phytozome [http://phytozome.net] for Mt (v3.0), Pv (v1.0), Gm (v1.1), International Chickpea Genetics and Genome Sequencing Consortium [http://www.icrisat.org/gt-bt/ICGGC/GenomeSequencing.htm] for Ca (v1.0), Kazusa DNA Research Institute [http://www.kazusa.or.jp] for Lj (v2.5) and International Initiative for Pigeonpea Genomics [http://www.icrisat.org/gt-bt/iipg/genomedata.zip] for Cc (v5.0).

Sequence analysis

Standalone BLAST package, ncbi-blast-2.2.25+ from NCBI was used for homologs search analysis. All NF-related genes were compared against all six legume's CDS using BLASTN program. Further, homology hits were filtered on criterion of 70 % identity and e-value cut-off of ≤1E−50 using in-house perl script. All potential hits or homologous sequences were extracted from CDS databases of each legume. Finally, genes were selected by using a criteria of presence of homologs in at least four out of six legumes species (Table 1). All NF-related genes were clustered into gene families using orthoMCL v1.4 (Li et al., 2003). Bidirectional best hits by BLAST was used for confirmation of orthologs in six species (Zhang and Leong, 2010).

Table 1.

List of 20 NF-related genes analyzed in six legume species.

| Gene name* | Medicago truncatula | Cicer arietinum | Lotus japonicus** | Cajanus cajan | Phaseolus vulgaris | Glycine max*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MtDMI11 | Medtr2g005620 | Ca_00033 | Lj6.CM0508.260.r2.m | C.cajan_17266 | Phvulv091019046m | Glyma12g28860 |

| C.cajan_11017 | Glyma16g00500 | |||||

| Glyma19g45310 | ||||||

| MtDMI22 | Medtr5g032400 | Ca_11537 | Lj2.CM0177.340.r2.m | C.cajan_12295 | Phvulv091027352m | Glyma09g33510 |

| Ca_17066 | Glyma01g02460 | |||||

| MtDMI33 | Medtr8g047760 | Ca_15707 | Lj3.LjT02O17.60.r2.m | C.cajan_46131 | Phvulv091013422m | Glyma15g35070 |

| Medtr5g009940 | Glyma08g24360 | |||||

| Glyma10g11020 | ||||||

| MtERN14 | Medtr7g102550 | Ca_08232 | Lj1.CM0104.2670.r2.m | C.cajan_08385 | Phvulv091004951m | Glyma16g04410 |

| Medtr6g031080 | C.cajan_16144 | Glyma19g29000 | ||||

| MtERN35 | Medtr6g015110 | Ca_08582 | Lj4.CM0046.750.r2.a | C.cajan_23330 | Phvulv091030938m | Glyma08g12130 |

| Medtr4g134350 | Glyma05g29011 | |||||

| MtFLOT26 | Medtr3g137870 | C.cajan_09162 | Phvulv091009868m | Glyma06g06930 | ||

| Medtr1g099720 | Glyma04g06830 | |||||

| MtIPD37 | Medtr5g027010 | Ca_10616 | Lj2.CM0803.150.r2.m | C.cajan_12408 | Phvulv091016359m | Glyma01g35255 |

| Glyma09g34695 | ||||||

| MtLIN8 | Medtr1g112060 | Ca_08341 | Lj5.CM0909.400.r2.m | C.cajan_22455 | Phvulv091027173m | Glyma10g33851 |

| Glyma12g29771 | ||||||

| MtLYK39 | Medtr5g093450 | Ca_10278 | Lj2.CM0545.250.r2.m | C.cajan_09999 | Phvulv091021871m | Glyma14g05060 |

| Medtr5g093440 | Lj6.CM0041.460.r2.a | C.cajan_15801 | Glyma02g43860 | |||

| Medtr5g093730 | Glyma02g43850 | |||||

| Medtr5g093410 | ||||||

| MtLYR310 | Medtr5g019000 | Ca_02085 | Lj2.CM0323.420.r2.d | C.cajan_12623 | Phvulv091008254m | Glyma11g06750 |

| Glyma01g38550 | ||||||

| Glyma02g06700 | ||||||

| MtNFP10 | Medtr5g018990 | Ca_02086 | Lj2.CM0323.400.r2.d | C.cajan_12621 | Phvulv091008306m | Glyma11g06740 |

| Medtr8g093910 | Ca_16029 | Glyma01g38560 | ||||

| MtNIN11 | Medtr5g106690 | Ca_09832 | Lj2.CM0102.250.r2.m | C.cajan_33924 | Phvulv091031090m | Glyma06g00240 |

| C.cajan_37712 | Phvulv091004689m | Glyma04g00210 | ||||

| Glyma02g48080 | ||||||

| MtNRT112 | Medtr5g093170 | Ca_10291 | Lj2.CM0826.350.r2.m | C.cajan_09986 | Phvulv091021785m | Glyma02g43740 |

| Lj2.CM0826.370.r2.m | Glyma14g05170 | |||||

| Lj2.CM0545.330.r2.m | ||||||

| MtNSP113 | Medtr8g025000 | Ca_10004 | Lj3.CM0416.1260.r2.d | C.cajan_27701 | Phvulv091018505m | Glyma07g04430 |

| Medtr5g015580 | Phvulv091030806m | Glyma16g01020 | ||||

| Medtr8g101580 | Phvulv091007340m | Glyma05g22460 | ||||

| MtNSP213 | Medtr3g097800 | Ca_26279 | Lj1.CM1976.90.r2.m | C.cajan_01355 | Phvulv091012665m | Glyma04g43090 |

| Medtr5g065380 | Ca_23494 | C.cajan_32376 | Glyma06g11610 | |||

| Glyma13g02840 | ||||||

| MtRRP114 | Medtr1g074280 | Ca_26056 | Lj5.CM1077.650.r2.m | C.cajan_33337 | Phvulv091005582m | Glyma13g21080 |

| Ca_19055 | Glyma10g07190 | |||||

| MtSKL115 | Medtr7g121800 | Ca_12043 | Lj1.CM0012.1100.r2.m | C.cajan_45110 | Phvulv091008769m | Glyma03g33850 |

| Glyma13g20810 | ||||||

| Glyma10g06610 | ||||||

| MtSUNN16 | Medtr4g096420 | Ca_15399 | Lj3.CM0091.1690.r2.m | C.cajan_21258 | Phvulv091015304m | Glyma12g04390 |

| Medtr4g096400 | Ca_09375 | C.cajan_24880 | Glyma11g12186 | |||

| C.cajan_39327 | ||||||

| GmN5617 | Medtr1g146810 | Ca_13985 | Lj5.CM0492.390.r2.m | C.cajan_07899 | Phvulv091005854m | Glyma10g44180 |

| Ca_26114 | Lj1.CM0001.650.r2.m | C.cajan_37827 | Glyma20g38950 | |||

| Lj1.CM0001.690.r2.m | C.cajan_46126 | Glyma13g12484 | ||||

| Lj1.CM0001.710.r2.m | Glyma19g29920 | |||||

| Glyma19g29880 | ||||||

| GmENOD9318 | Medtr8g119590 | Ca_06646 | C.cajan_46055 | Phvulv091017136m | Glyma06g24760 | |

| C.cajan_26197 | Glyma05g08400 | |||||

| C.cajan_26199 | Glyma17g12600 | |||||

| Glyma17g12610 | ||||||

| Glyma05g08380 |

Orthologs by bidirectional best hit and OrthoMCL were mentioned on the top of the genes listed for each species except GmENOD93 (Medtr8g119590 and Ca_06646).

Gene names as per the research articles in which these genes were cloned and published.

Gene name of Lj were changed from chr to Lj for convenience.

Underlined genes of Gm were present in syntenic regions.

(Ané et al., 2004),

(Endre et al., 2002),

(Lévy et al., 2004),

(Middleton et al., 2007),

(Andriankaja et al., 2007),

(Haney and Long, 2010),

(Messinese et al., 2007),

(Kiss et al., 2009),

(Smit et al., 2007),

(Arrighi et al., 2006),

(Marsh et al., 2007),

(Morère-Le Paven et al., 2011),

(Hirsch et al., 2009),

(Arrighi et al., 2008),

(Penmetsa et al., 2008),

(Elise et al., 2005),

(Kouchi and Hata, 1995),

(Kouchi and Hata, 1993).

All selected homologous genes were subjected for multiple sequence alignment using Clustal 2 (http://www.clustal.org/clustal2) with default parameter. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by MEGA5 using the neighbor-joining, maximum-likelihood, and maximum-parsimony method with 1000 replicates in the bootstrap test (Tamura et al., 2011). All positions containing gaps and missing sequences were not calculated. Sequence distance, Ks and Ka were calculated between all gene pairs in each NF-related gene by MEGA5. Sequence distance which indicates the extent of similarity between homologs (including orthologs and paralogs) was calculated by the number of base substitutions per site.

Results and discussion

Organization of selected nitrogen fixation-related genes

Genes responsible for signal pathway and nodulation were also included in the list of NF-related genes in the broad concept of NF pathway. Although many NF-related genes were cloned using traditional genetics (e.g., map-based cloning and forward genetics) approaches in Mt and Lj, soybean genome sequencing provided occurrence of 52 NF-related genes. All these 52 genes were searched for homology in the genome sequences of Mt, Lj, Ca, Pv, and Cc. By searching for the presence of orthologs in at least four of six legume species surveyed, a total of 20 NF-related genes were selected for further analysis (Table 1). Orthologs relationships in six legumes were confirmed by bidirectional best hit and orthoMCL. Due to the recent duplication of Gm genome, it has two or more homologs (Schmutz et al., 2010). As nomenclature for majority of NF-related genes were given in cloning studies in Mt and Lj, identified orthologs in the legume genomes surveyed were named accordingly. All 20 NF-related genes were used for placing them on chromosomes/pseudomolecules based on sequence analysis across all the legume crops (Figure 1). For instance, in the case of Mt genome, there are seven genes (DMI2, IPD3, LYK3, LYR3, NFP, NIN, and NRT1) located on Mt5. Although MtNFP and MtLYR3 genes were present next to each other, these genes have their own orthologs in different species. As expected because of two times of genome duplication in Gm, all genes had at least two paralogs in the genome and most of them were present in the syntenic regions and 18 genes of 20 (except LIN and FLOT2) had inparalogs. In the case of DMI3 ortholog in Gm, it has a paralog but not present in the syntenic region. Therefore, it is possible that one copy of LIN and FLOT2 could have been deleted and a paralog of DMI3 might have been relocated after the recent duplication in Gm genome.

Figure 1.

Comparative genome location of 16 genes in six legume species. Chromosome/pseudomolecule/linkage group have been shown by arc. Legume species have shown in different colors: Mt-red, Ca-orange, Lj-yellow, Cc-green, Pv-blue, and Gm-dark blue, purple. Gap indicates that the gene is on unmapped scaffold.

Overall sequence distances and synonymous substitution rates

Sequence distance, Ks as well as Ka values were calculated for all possible 922 homolog pairs of 20 NF-related genes in legume genomes surveyed. Comparison of these data showed the lowest sequence distance for 15 out 20 (75%) NF-related genes in Gm-Gm and 14 (70%) genes showed the lowest Ks in Gm-Gm (Supplementary Table 1). The lowest sequence distance and Ks resulted from recently duplicated genes in Gm. After excluding Gm-Gm (paralog) relationship, Gm-Cc orthologs for seven genes have the lowest sequence distance and eight genes have the lowest Ks. On the contrary, Mt-Pv orthologs for six genes have the highest sequence distance and Ks. These observations imply that Gm-Cc could be the closest and Mt-Pv would be the farthest in evolution of six species. To check the evolutionary distance from Gm to the other five species, Ks medians (excluding Ks from tandem repeats) were compared (Supplementary Table 2). Gm-Gm (0.181) has the least Ks median, Gm-Cc (0.212) and Gm-Pv (0.212) have same Ks median, Gm-Lj (0.331) and Gm-Ca (0.336) have almost similar Ks median and Gm-Mt (0.398) has the highest Ks median. Based on Ks median values, both Pv and Cc are the closest to Gm followed by Lj and Ca, and Mt is the farthest from Gm. While analyzing the evolutionary distances of different species from Mt, Mt- Ca has the lowest Ks median (0.282), and higher Ks median was observed for Mt-Cc (0.405) and Mt-Pv (0.400). Therefore, by considering only Ks median values, it is not possible to infer the farthest species from Mt in the legume evolution. In summary, by considering the maximum number of genes with least Ks and the lowest Ks median across the genes for all orthologs of 20 NF-related genes, Gm-Cc were found to be the closest followed by Gm-Pv and Mt-Pv were found to be the farthest.

It is well known that Ka is smaller than Ks in natural evolution because of conservation of functional coding genes, therefore non-synonymous change was less frequent in mutation of nucleotides during evolution (Hurst, 2002; Nekrutenko et al., 2002). Average Ka/Ks across 20 NF-related genes in six legumes is 0.69 (Supplementary Table 2). The lower Ka/Ks value (<1) in NF-related genes suggested that most of the genes have remained under negative selection in the course of evolution (Suzuki and Gojobori, 1999). Higher Ka/Ks value (>1) was observed only for ENOD93 (1.461) but this also does not represent a strong positive selection. Interestingly, about 50% (9 genes) of NF-related genes such as DMI3 (0.245), FLOT2 (0.193), NRT1 (0.255) had very low (<<1) Ka/Ks values which showed a very strong negative selection pressure in course of evolution of legume species. As earlier studies indicated that genes with essential functions have lower Ka/Ks values (Lam et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2012), this study once again underlines the importance and essentiality of the NF-related genes for legume species. Because of this reason, these genes have remained more conserved in speciation and rearrangements during the evolution of legume species.

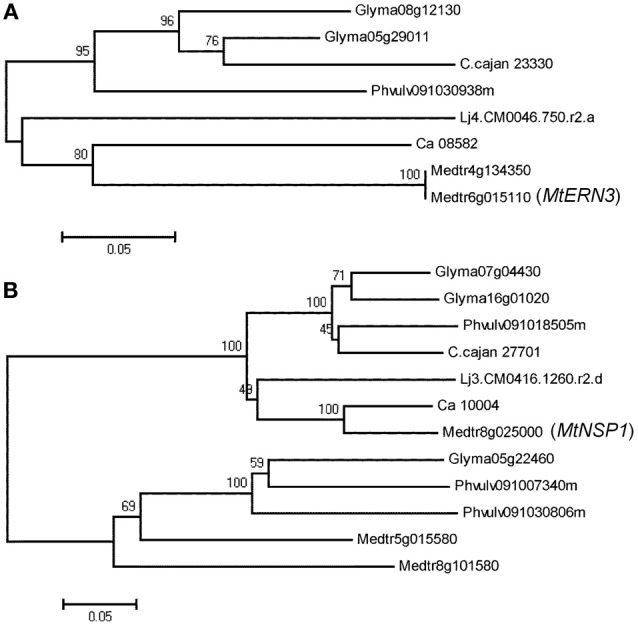

Phylogenetic relationship analysis with neighbor-joining method based on sequence diversity for all analyzed genes in the six legume species showed two types of phylogenetic trees. For instance, in the case of five genes (DMI2, ERN3, IPD3, NRT1 and RRP1), only one cluster (clade) was observed (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure 1). In the remaining 15 genes, phylogenetic trees consist of two clusters (Figure 2B). Genes belonging to the first type of phylogenetic trees, that have only one cluster (and not have outparalogs), can be considered to be originated from the single gene of a common ancestor. On the other hand, genes belonging to the second type of phylogenetic trees, that consist of two clusters, may be considered to be duplicated before speciation (Koonin, 2005). While analyzing two types of clusters for all the genes, average sequence distances within and between clusters were observed as 0.237 and 0.437, respectively. Similarly, Ks values within and between clusters were 0.290 and 0.510, respectively. This Ks value (0.510) supports that genes belonging to different clusters could be originated from the different genes of the common ancestor before speciation, because Ks peaks were observed at Ks 0.4 (Koonin, 2005). In addition to neighbor-joining method, maximum-likelihood and maximum-parsimony methods were also used for phylogenetic analysis (Supplementary Figures 2, 3). Most of the cases displayed similar trees compared with neighbor-joining trees except LIN, LYK3, and LYR3. These three genes had one or two genes in different cluster. OrthoMCL and bidirectional best hit were also used for confirmation of orthologs and they showed same results (Supplementary Table 3). It is an interesting observation that ENOD93 had two different orthologs in Gm and Cc by OrthoMCL and it was identical to the phylogenetic tree of ENOD93 which had only three genes in the first cluster (Supplementary Figure 1). Glyma06g24760, Phvulv091017136m and C.cajan_46055 are orthologs and the other genes could be outparalogs to them.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic trees based on sequence data using the neighbor-joining method. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown above the branches (A). ERN3 has one cluster. (B). NSP1 has two clusters.

Elucidation of duplication and divergence

In general, genome of majority of plant species might have undergone one or more of following type of duplications: (1) ancient genome duplication, that occurred >100 MYA (Pfeil et al., 2005), (2) segmental duplication, that contains duplication of several genes in a stretch, (3) tandem duplication that occurs at gene level, and (4) recent genome duplication. However, peaks could be observed only in the case of genome duplication. In past, Ks peaks were compared and analyzed in detail to explain evolutionary processes (Koch et al., 2000; Blanc and Wolfe, 2004; Shoemaker et al., 2006).

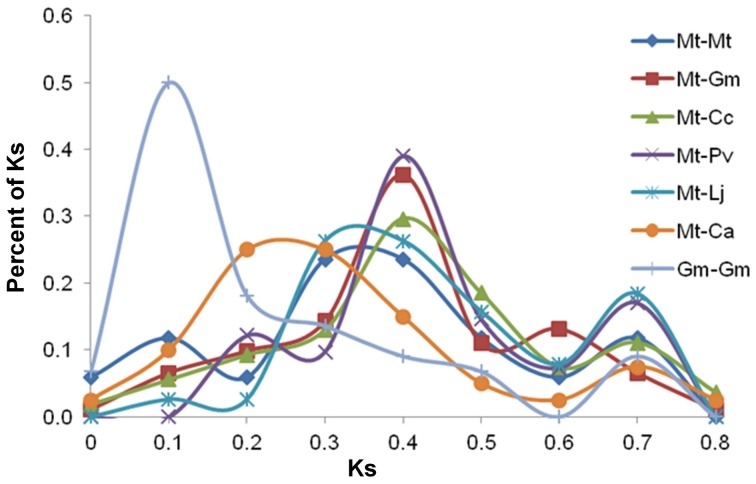

Comparison of all 20 NF-related genes with their orthologs of all species provided three types of the peaks (Figure 3). The first type of peak was at Ks 0.1 and restricted to only Gm-Gm. This peak indicates recent whole genome duplication which occurred only in Gm genome (Pfeil et al., 2005; Schmutz et al., 2010) but not in any other legume. The second type of peaks at or near Ks 0.4 were present in Mt-Gm, Mt-Cc, Mt-Pv, Mt-Mt, and Mt-Lj. In the case of Mt-Ca orthologs, the second type of peak was, however, present between Ks 0.2 and 0.3. These analyses indicate that speciation might have happened together in Phaseolids species (Gm, Pv, Cc) followed by Lj, and then Mt and Ca. The third type of peaks at Ks 0.6 or Ks 0.7 were present in Mt-Ca, Mt-Cc, Mt-Lj, Mt-Pv, and Mt-Gm. This might correspond with ancient duplication event before speciation (Cannon et al., 2006). As it is not known that how frequently rearrangements had happened after ancient duplication, the peaks observed at Ks 0.6 or 0.7 are smaller as compared to the peaks of second and first type. These analyses indicate that there were many deletions and relocations in genomes after ancient duplication (Pfeil et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2009). The third type of peaks were observed in only few studies earlier because these peaks should have come from outparalogs which could be found abundantly in Gm but not enough in other legumes (Blanc and Wolfe, 2004; Shoemaker et al., 2006). However, because of the importance of NF, 10 out of 20 NF-related genes have outparalogs in Pv, Cc, Ca, and Lj. However, complete conserved outparalogs were not observed across all six legumes for any NF-related genes (Supplementary Figure 1). Only LYK3 and N56 genes had outparalogs from four species and other genes had less than three outparalogs.

Figure 3.

Ks proportional plot based on sequence data for 20 NF-related genes. This plot shows peaks based on Ks values between Mt and other five legume species and one peak based on Ks values of inparalogs of Gm (Gm-Gm). The plots shows three types of peaks: (i) the first type of peak observed at Ks 0.1 indicates recent genome duplication in Gm, (ii) the second type of peaks observed at or near Ks 0.4 indicate speciation, and (iii) the third type of peaks observed at Ks 0.6 or Ks 0.7 correspond to ancient genome duplication.

Differentiation of inparalogs and outparalogs

Phylogenetic analysis provided two types of phylogenetic trees. Five genes had one cluster (clade) that contained only orthologs and 15 genes had two clusters that contained orthologs and outparalagos. Average Ks for orthologs for all 20 NF-related genes is 0.29 but average Ks in outparalogs for 15 NF-related genes is 0.51. For example, there are three DMI1 orthologs of Gm namely, Glyma12g28860, Glyma16g00500, and Glyma19g45310 (Table 1). Glyma12g28860 and Glyma16g00500 are inparalogs to each other because they are in syntenic region and their sequences are very similar (Ks 0.04). But Glyma19g45310 is outparalog to Glyma12g28860 (Ks 0.34) and Glyma16g00500 (Ks 0.34). Phylogenetic tree indicated that Glyma12g28860 and Glyma16g00500 are in the same cluster and Glyma19g45310 belongs to different cluster (Supplementary Figure 1). Similarly, in the case of phylogenetic tree for NSP1, in addition to the main clusters that had the MtNSP1 and its orthologs for Ca, Lj, Cc, Pv, and Gm (two inparalogs), there is one extra cluster which has two Mt genes, two Pv genes and one Gm gene (Figure 2B). In these genes, Glyma05g22460 and Glyma07g04430 had Ks 0.685, and Glyma05g22460 and Glyma16g01020 had Ks 0.703. In both of these cases, Ks is higher than average Ks of orthologs (0.29). Furthermore, extra 5 genes in the second cluster have high Ks as compared to the genes present in the first cluster. In the first cluster, Glyma07g04430 and Glyma16g01020 are inparalogs but inparalog of Glyma05g22460 might have been deleted. These analyses indicate that in the case of Gm, the gene (NSP1) of the common ancestor might have undergone one duplication before speciation, one duplication after speciation and in total there might be four genes. However, one of these four genes might have been deleted after recent genome duplication. As a result, the Gm genome has only three NSP1 genes. In another example of Mt, MtLYK3 (Medtr5g093450) and its three paralogs (Medtr5g093410, Medtr5g093440, and Medtr5g093730), the phylogenetic tree classifies one paralog (Medtr5g093440) with the MtLYK3 gene (Medtr5g093450) in one cluster and the remaining two paralogs (Medtr5g093410 and Medtr5g093730) in the other cluster (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1). Their average Ks for inparalogs (Medtr5g093440-Medtr5g093450 and Medtr5g093410-Medtr5g093730) is 0.21 and for outparalogs is 0.39. These analyses suggest that MtLYK3 has four copies as a result of ancient duplication and then followed by tandem duplication. It is interesting to note that they are located very closely and they have less Ks than other outparalogs. MtLYK3 is the only one case which has outparalogs together at very close position. On the other hand, in other cases, closely located genes are inparalogs. These cases include NRT1 genes in Lj, N56 genes in Lj and Gm, ENOD93 genes in Cc and Gm, SUNN genes in Mt.

Interesting cases

Ks value and Ks peaks have been used for understanding of genome evolution in many studies. In our study with 20 NF-related genes, most of the observed cases corresponded to results or hypothesis of previous studies in legumes (Schlueter et al., 2004, 2007; Pfeil et al., 2005; Shoemaker et al., 2006; Shin et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009). However, there were at least three cases where we don't have sufficient explanation.

The Ks proportional plot showed no peak at Ks 0.4 for Gm-Gm though Mt-Gm had a peak at Ks 0.4 (Figure 3). In all earlier studies (Gm-Gm, Mt-Gm) based on whole genome sequences, BAC sequences, ESTs or specific gene families, a peak was observed near Ks 0.4. This peak reflected divergence between Hologalegina and Phaseolids (Schlueter et al., 2004, 2007; Pfeil et al., 2005; Shin et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2009; Schmutz et al., 2010).

MtNFP and MtNYR3 encode a same lysin motif receptor kinase and these genes are located “next to each other” in Mt (Medtr5g018990 and Medtr5g01900), Gm (Glyma11g06740 and Glyma11g06750) and Ca (Ca_02086 and Ca_02085) (Supplementary Figure 4). On the other hand, orthologs of NFP and NYR3 were present “very near” (and not “next to each other”) in Pv, Cc, and Lj. In general, the genes which are present “next to each other” are the cases of inparalogs (tandem duplication). However, this (MtNFP and MtNYR3) seems to be the only case where two independent genes (they might have been duplicated before speciation) are present next to each other and they have their own orthologs. In Mt genome sequences, many local gene duplications were found so if those paralogs were retained, sub- or neo-functionalization could be expected, especially essential genes like NF-related genes (Young et al., 2011).

The respective phylogenetic trees for NFP, NIN, and ENOD93 genes seem to have outparalogs but Ks of these genes is less than 0.4 (Supplementary Table 1). The phylogenetic trees for these genes have the same type (two clusters) as the other 12 genes (DMI1, DMI3, ERN1, FLOT2, LIN, LYK3, LYR3, NSP1, NSP2, SKL1, SUNN, and N56) which have outparalogs. Average of Ks values between outparalogs in these 12 genes were >0.40. Several researches in comparing sequences with expression level or their functions suggested that after duplication there was a bias in which genes were retained or silenced (Shoemaker et al., 2006). And even a specific gene or region could have significantly lower Ks (Koch et al., 2000; Schlueter et al., 2007). These researches are similar with our observation in three genes.

Summary

Although many comparative genomic studies have been conducted using whole genome sequences, BACs and genes, majority of these studies were restricted to one species or some combination of Mt, Gm, Lj, and Pv. This is the first study that employs comparative sequence analysis of NF-related genes to understand genome evolution of six legumes which include two model legumes (Lj and Mt), two commercial legumes (Pv and Gm) and two “so called” orphan legumes (Cc and Ca). Sequence distances and Ks values suggested that Gm-Cc is the closest and Mt-Pv is the farthest in the divergence of six legumes. Low Ka/Ks of NF-related genes indicated that they were conserved in evolution and NF is a functionally essential trait of legumes. Occurrence of the third type of peak near Ks 0.7 and outparalogs in the case of phylogenetic trees for 15 NF-related genes reconfirmed the ancient duplication. Due to large and small scale of rearrangements of DNA during the course of evolution of the six legume species, observation of three interesting cases (no peak at Ks 0.4 in Gm-Gm, location of two independent genes next to each other and low Ks values for outparalogs in three genes) could not be fully explained. Though a great amount of sequence information is available for these six legume species, we are still in the process of understanding evolution of genes, genomes, and species.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work has been undertaken as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Grain Legumes. ICRISAT is a member of CGIAR Consortium. This study has been supported by US National Science Foundation (NSF)—Basic Research Enabling Agriculture in Developing Countries (BREAD) grant entitled “Overcoming the Domestication Bottleneck for Symbiotic Nitrogen Fixation in Legumes.” Sequence data of Pv were produced by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (http://phytozome.net).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: www.frontiersin.org/Plant_Genetics_and_Genomics/10.3389/fpls.2013.00300/abstract

References

- Andriankaja A., Boisson-Dernier A., Frances L., Sauviac L., Jauneau A., Barker D. G., et al. (2007). AP2-ERF transcription factors mediate Nod factor dependent Mt ENOD11 activation in root hairs via a novel cis-regulatory motif. Plant Cell 19, 2866–2885 10.1105/tpc.107.052944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ané J.-M., Kiss G. B., Riely B. K., Penmetsa R. V., Oldroyd G. E. D., Ayax C., et al. (2004). Medicago truncatula DMI1 required for bacterial and fungal symbioses in legumes. Science 303, 1364–1367 10.1126/science.1092986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi J.-F., Barre A., Ben Amor B., Bersoult A., Soriano L. C., Mirabella R., et al. (2006). The Medicago truncatula lysine motif-receptor-like kinase gene family includes NFP and new nodule-expressed genes. Plant Physiol. 142, 265–279 10.1104/pp.106.084657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrighi J. F., Godfroy O., De Billy F., Saurat O., Jauneau A., Gough C. (2008). The RPG gene of Medicago truncatula controls Rhizobium-directed polar growth during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9817–9822 10.1073/pnas.0710273105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G., Wolfe K. H. (2004). Widespread paleopolyploidy in model plant species inferred from age distributions of duplicate genes. Plant Cell 16, 1667–1678 10.1105/tpc.021345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon S. B., Sterck L., Rombauts S., Sato S., Cheung F., Gouzy J., et al. (2006). Legume genome evolution viewed through the Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14959–14964 10.1073/pnas.0603228103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elise S., Etienne-Pascal J., Fernanda C.-N., Gérard D., Julia F. (2005). The Medicago truncatula SUNN gene encodes a CLV1-like leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase that regulates nodule number and root length. Plant Mol. Biol. 58, 809–822 10.1007/s11103-005-8102-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endre G., Kereszt A., Kevei Z., Mihacea S., Kalo P., Kiss G. B. (2002). A receptor kinase gene regulating symbiotic nodule development. Nature 417, 962–966 10.1038/nature00842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney C. H., Long S. R. (2010). Plant flotillins are required for infection by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 478–483 10.1073/pnas.0910081107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch S., Kim J., Muñoz A., Heckmann A. B., Downie J. A., Oldroyd G. E. D. (2009). GRAS proteins form a DNA binding complex to induce gene expression during nodulation signaling in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 21, 545–557 10.1105/tpc.108.064501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst L. D. (2002). The Ka/Ks ratio: diagnosing the form of sequence evolution. Trends. Genet. 18, 486 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02722-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. D., Shin J. H., Van K., Kim D. H., Lee S.-H. (2009). Dynamic rearrangements determine genome organization and useful traits in soybean. Plant Physiol. 151, 1066–1076 10.1104/pp.109.141739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss E., Olah B., Kalo P., Morales M., Heckmann A. B., Borbola A., et al. (2009). LIN, a novel type of U-box/WD40 protein, controls early infection by rhizobia in legumes. Plant Physiol. 151, 1239–1249 10.1104/pp.109.143933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M. A., Haubold B., Mitchell-Olds T. (2000). Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 1483–1498 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonin E. V. (2005). Orthologs, paralogs, and evolutionary genomics. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 309–338 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi H., Hata S. (1993). Isolation and characterization of novel nodulin cDNAs representing genes expressed at early stages of soybean nodule development. Mol. Gen. Genet. 238, 106–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi H., Hata S. (1995). GmN56, a novel nodule-specific cDNA from soybean root nodules encodes a protein homologous to isopropylmalate synthase and homocitrate synthase. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 8, 172–176 10.1094/MPMI-8-0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouchi H., Imaizumi-Anraku H., Hayashi M., Hakoyama T., Nakagawa T., Umehara Y., et al. (2010). How many peas in a pod? Legume genes responsible for mutualistic symbioses underground. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 1381–1397 10.1093/pcp/pcq107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam H. M., Xu X., Liu X., Chen W., Yang G., Wong F. L., et al. (2010). Resequencing of 31 wild and cultivated soybean genomes identifies patterns of genetic diversity and selection. Nat. Genet. 42, 1053–1059 10.1038/ng.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin M., Herendeen P. S., Wojciechowski M. F. (2005). Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the tertiary. Syst. Biol. 54, 575–594 10.1080/10635150590947131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévy J., Bres C., Geurts R., Chalhoub B., Kulikova O., Duc G., et al. (2004). A putative Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase required for bacterial and fungal symbioses. Science 303, 1361–1364 10.1126/science.1093038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Stoeckert C. J., Roos D. S. (2003). OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189 10.1101/gr.1224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh J. F., Rakocevic A., Mitra R. M., Brocard L., Sun J., Eschstruth A., et al. (2007). Medicago truncatula NIN is essential for rhizobial-independent nodule organogenesis induced by autoactive calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Plant Physiol. 144, 324–335 10.1104/pp.106.093021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messinese E., Mun J. H., Yeun L. H., Jayaraman D., Rouge P., Barre A., et al. (2007). A novel nuclear protein interacts with the symbiotic DMI3 calcium- and calmodulin-dependent protein kinase of Medicago truncatula. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 912–921 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton P. H., Jakab J., Penmetsa R. V., Starker C. G., Doll J., Kaló P., et al. (2007). An ERF transcription factor in Medicagot truncatula that is essential for Nod factor signal transduction. Plant Cell 19, 1221–1234 10.1105/tpc.106.048264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morére-Le Paven M.-C., Viau L., Hamon A., Vandecasteele C., Pellizzaro A., Bourdin C., et al. (2011). Characterization of a dual-affinity nitrate transporter MtNRT1.3 in the model legume Medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 5595–5605 10.1093/jxb/err243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrutenko A., Makova K. D., Li W. H. (2002). The Ka/Ks ratio test for assessing the protein-coding potential of genomic regions: an empirical and simulation study. Genome Res. 12, 198–202 10.1101/gr.200901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penmetsa R. V., Uribe P., Anderson J., Lichtenzveig J., Gish J. C., Nam Y. W., et al. (2008). The Medicago truncatula ortholog of Arabidopsis EIN2, sickle, is a negative regulator of symbiotic and pathogenic microbial associations. Plant J. 55, 580–595 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeil B. E., Schlueter J. A., Shoemaker R. C., Doyle J. J. (2005). Placing paleopolyploidy in relation to taxon divergence: a phylogenetic analysis in legumes using 39 gene families. Syst. Biol. 54, 441–454 10.1080/10635150590945359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S., Nakamura Y., Kaneko T., Asamizu E., Kato T., Nakao M., et al. (2008). Genome structure of the legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 15, 227–239 10.1093/dnares/dsn008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter J. A., Dixon P., Granger C., Grant D., Clark L., Doyle J. J., et al. (2004). Mining EST databases to resolve evolutionary events in major crop species. Genome 47, 868–876 10.1139/g04-047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter J. A., Vaslenko-Sanders I. F., Deshpande S., Yi J., Siegfried M., Roe B. A., et al. (2007). The FAD2 gene family of soybean: Insights into the structural and functional divergence of a paleopolyploid genome. Crop Sci. 47, S14–S26 [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J., Cannon S. B., Schlueter J., Ma J., Mitros T., Nelson W., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463, 178–183 10.1038/nature08670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. H., Van K., Kim D. H., Kim K. D., Jang Y. E., Choi B. S., et al. (2008). The lipoxygenase gene family: a genomic fossil of shared polyploidy between Glycine max and Medicago truncatula. BMC Plant. Biol. 8:133 10.1186/1471-2229-8-133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker R. C., Schlueter J., Doyle J. J. (2006). Paleopolyploidy and gene duplication in soybean and other legumes. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 9, 104–109 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit P., Limpens E., Geurts R., Fedorova E., Dolgikh E., Gough C., et al. (2007). Medicago LYK3, an entry receptor in rhizobial nodulation factor signaling. Plant Physiol. 145, 183–191 10.1104/pp.107.100495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprent J. I. (2000). Nodulation as a taxonomic tool, in Advance in Legume Systematics, Part 9, eds Herendeen P. S., Bruneau A. (Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens; ), 21–44 [Google Scholar]

- Sprent J. I. (2007). Evolution and diversity of legume symbiosis, in Nitrogen-Fixing Leguminous Symbioses, eds Dilworth M., James E., Sprent J., Newton W. (Dordrecht: Springer; ), 1–21 [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y., Gojobori T. (1999). A method for detecting positive selection at single amino acid sites. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1315–1328 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., Kumar S. (2011). MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R. K., Chen W., Li Y., Bharti A. K., Saxena R. K., Schlueter J. A., et al. (2012). Draft genome sequence of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan), an orphan legume crop of resource-poor farmers. Nat. Biotech. 30, 83–89 10.1038/nbt.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R. K., Song C., Saxena R. K., Azam S., Yu S., Sharpe A. G., et al. (2013). Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotech. 31, 240–246 10.1038/nbt.2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Liu X., Ge S., Jensen J. D., Hu F., Li X., et al. (2012). Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronomically important genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 105–111 10.1038/nbt.2050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young N. D., Debelle F., Oldroyd G. E., Geurts R., Cannon S. B., Udvardi M. K., et al. (2011). The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature 480, 520–524 10.1038/nature10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Leong H. W. (2010). Bidirectional best hit r-window gene clusters. BMC Bioinformatics 11:S63 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S1-S63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.