Abstract

FSH production is important for human gametogenesis. In addition to inactivating mutations in the FSHB gene, which result in infertility in both sexes, a G/T single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at −211 relative to the transcription start site of the 5′ untranslated region of FSHB has been reported to be associated with reduced serum FSH levels in men. In this study, we sought to identify the potential mechanism by which the −211 SNP reduces FSH levels. Although the SNP resides in a putative hormone response element, we showed that, unlike the murine gene, human FSHB was not induced by androgens or progestins in gonadotropes. On the other hand, we found that the LHX3 homeodomain transcription factor bound to an 11-bp element in the human FSHB promoter that includes the −211 nucleotide. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that LHX3 bound with greater affinity to the wild-type human FSHB promoter compared with the −211 G/T mutation and that LHX3 binding was more effectively competed with excess wild-type oligonucleotide than with the SNP. Finally, we showed that FSHB transcription was decreased in gonadotrope cells with the −211 G/T mutation compared with the wild-type FSHB promoter. Altogether, our results suggest that decreased serum FSH levels in men with the SNP likely result from reduced LHX3 binding and induction of FSHB transcription.

Follicle-stimulating hormone is produced specifically by gonadotrope cells in the anterior pituitary and plays a critical role in mammalian fertility. FSH is required for ovarian folliculogenesis in females, whereas in males it promotes spermatogenesis in conjunction with testosterone (1, 2). FSH is a heterodimeric glycoprotein composed of an α-subunit that is shared in common with LH and TSH, and a unique β-subunit specific to FSH that confers biological specificity (3). Transcription of FSHB appears to be a rate-limiting step in the production of mature FSH and is regulated by several hormones, including GnRH and activin (4, 5).

Mutations that inactivate the FSHB gene, resulting in infertility, have been identified in both men and women, including 3 men with azoospermia, small testes, and decreased serum FSH levels and 6 women with delayed puberty and isolated FSH deficiency (6–12). In addition to these inactivating mutations, a G/T single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) at −211 relative to the transcription start site in the 5′ untranslated region of FSHB was associated with reduced serum FSH in European men from the Baltics, Italy, and Germany (13–17). Serum FSH levels were reduced 15.7% in G/T heterozygotes and 40% in TT homozygotes when compared with GG homozygotes in a cohort of Estonian men (13). Additionally, a significant increase of G/T heterozygotes (25.1% vs 22.4%) and TT homozygotes (2.4% vs 1.1%) was reported in patients with male factor infertility compared with normal men (18). A significant increase of TT homozygotes (2.5%) in oligozoospermic versus normozoospermic men was also found in an Italian study (16).

Because the −211 G/T SNP is associated with reduced serum FSH levels in men, we investigated the molecular mechanisms responsible for the decreased FSH levels. Previous studies have demonstrated that the nucleotide in the murine Fshb promoter corresponding to the −211 nucleotide in the human promoter reduces steroid and activin responsiveness (19–22). Because the −211 G/T SNP is located in the midst of a putative hormone response element (HRE) that is conserved in mammals (19), it has been suggested that the reduced FSH levels in men with the −211 SNP are due to decreased steroid hormone responsiveness. However, unlike the murine promoter, we recently showed that the human FSHB promoter was not significantly induced by progestins or activin in immortalized gonadotrope cells (22). Although insertion of a Sma/mothers against decapentaplegic-binding element into the human FSHB promoter was sufficient to increase promoter responsiveness to activin, insertion of an HRE into the promoter did not result in progestin responsiveness. These data suggest that another mechanism is responsible for the reduced FSH levels observed in men with the −211 SNP. In this study, we investigated what factor regulates FSHB transcription via the FSHB promoter region containing the −211 nucleotide. We also determined how the SNP affects binding of the relevant factor to the FSHB promoter and whether the SNP alters FSHB transcription in gonadotropes.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid constructs

Construction of the murine −1000 Fshb-luciferase (luc) reporter plasmid was described previously (21). Insertion of the −381 HRE into the human FSHB promoter was also described previously (22). The human −1028/+7 FSHB-luc plasmid was provided by Dr Daniel Bernard. The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, California) was used to generate the −211 G/T mutation in the human FSHB-luc plasmid. The rat androgen receptor (AR) expression vector, pSG5-rAR was provided by Dr Jorma Palvimo (23), whereas the pcDNA3-human LHX3 expression vector was provided by Dr Simon Rhodes.

Cell culture

Cell culture was performed using the LβT2 cell line, which has many characteristics of mature, differentiated gonadotropes (24, 25). Cells were maintained in 10-cm plates in DMEM (Mediatech Inc, Herndon, Virginia) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific Inc, Tarzana, California) and penicillin/streptomycin antibiotics (Gibco/Invitrogen, Grand Island, New York) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Transient transfection

LβT2 cells were seeded at 4.5 × 105 cells per well on 12-well plates and transfected 18 hours later, using Polyjet (SignaGen Laboratories, Rockville, Maryland), following the manufacturer's instructions. For all experiments, the cells were transfected with 400 ng of the indicated luc reporter plasmid and 200 ng of a β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter plasmid driven by the herpes virus thymidine kinase promoter to control for transfection efficiency. LβT2 cells were switched to serum-free media containing 0.1% BSA, 5 mg/L transferrin, and 50mM sodium selenite 6 hours after transfection. After overnight incubation in serum-free media, the cells were treated with vehicle (0.1% ethanol), 100nM methyltrienolone (R1881) (NEN Life Sciences, Boston, Massachusetts), or 100nM DHT (Sigma-Aldrich Co, St Louis, Missouri) for 24 hours.

Luciferase and β-gal assays

The cells were washed with 1× PBS and lysed with 0.1M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 0.2% Triton X-100. Lysed cells were assayed for luc activity using a buffer containing 100mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 15mM MgSO4, 10mM ATP, and 65μM luciferin. The β-gal activity was assayed using the Tropix Galacto-light assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California), according to the manufacturer's protocol. A Veritas Microplate Luminometer (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin) was used for both assays.

Statistical analyses

Transient transfections were performed in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least 3 times. The data were normalized for transfection efficiency by expressing luc activity relative to β-gal and relative to the empty pGL3 reporter plasmid to control for hormone effects on the vector DNA. The data were analyzed by Student's t test for independent samples or 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc comparisons with the Tukey-Kramer honestly significant difference test using the statistical package JMP version 10.0 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina). Significant differences were designated as P < .05.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Human LHX3 was transcribed and translated using a TnT coupled reticulolysate system (Promega). The oligonucleotides were end-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP, and 2 μL LβT2 nuclear extract or 4 μL TnT lysate was incubated with 1 fmol 32P-labeled oligonucleotide at 4°C for 30 minutes in a DNA-binding buffer [10mM HEPES [pH 7.8], 50mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1mM dithiothreitol, 2 μg poly(deoxyinosinic-deoxycytidylic) acid, and 10% glycerol]. After 30 minutes incubation, the DNA binding reactions were run on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (30:1 acrylamide/bisacrylamide) containing 2.5% glycerol in a 0.25× Tris/Borate/EDTA buffer. A rabbit Forkhead box L2 (FOXL2) (H-43) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California) and rabbit LHX3 (Lim3) antibody (U.S. Biological, Swampscott, Massachusetts) were used to supershift specific protein-DNA complexes; rabbit IgG was used as a control for nonspecific binding. The following oligonucleotides were used for EMSA: −360/−331 murine Fshb 5-AATTAAGACATATTTTGGTTTACCTTCGCA-3′, −213/−184 murine Fshb 5′-CATATCAGATTCGGTTTGTACAGAAACCAT-3′, −229/−200 human FSHB 5′-CTGTATCAAATTTAATTTGTACAAAATCAT-3′, and −229/−200 human FSHB with the −211 G/T mutation 5′-CTGTA-TCAAATTTAATTTTTACAAAATCAT-3′.

Results and Discussion

Transcription of the human FSHB gene is not regulated by androgens in gonadotrope cells

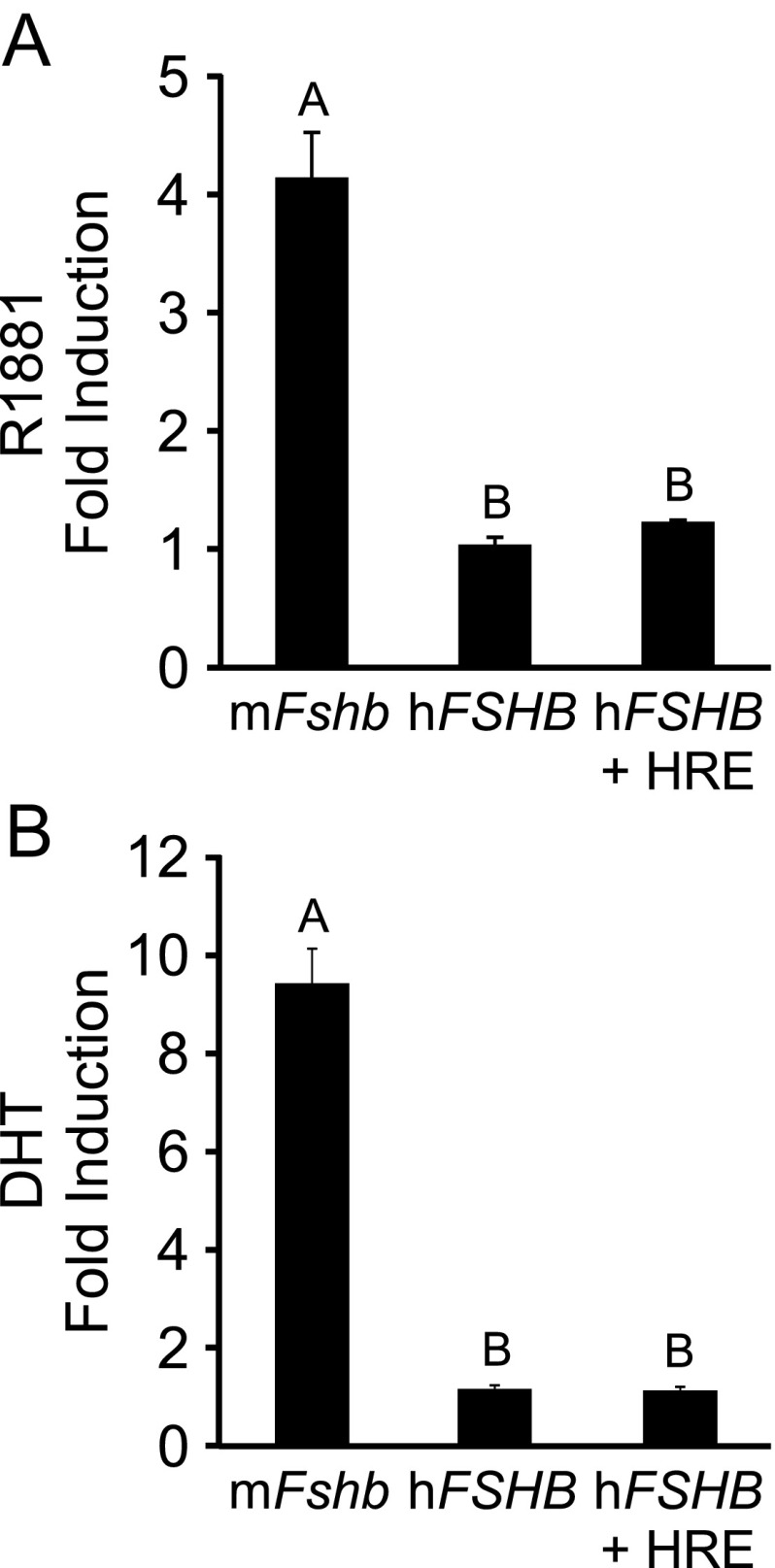

Although the human FSHB promoter does not appear to be responsive to progestins (22), it is possible that it can be induced by androgens. Because the −211 nucleotide is in the middle of a putative HRE, we tested whether human FSHB transcription was altered by treatment with a synthetic androgen, R1881, in immortalized LβT2 gonadotrope cells transfected with AR. As shown in Figure 1A, the −1000 murine Fshb-luc was induced 4-fold by 100nM R1881, whereas the −1028 human FSHB-luc was not induced. In addition, insertion of an HRE into the human FSHB promoter did not increase androgen responsiveness. We also determined that the human FSHB promoter was unresponsive to treatment with 100nM DHT (Figure 1B). In combination with our previous study demonstrating a lack of progestin responsiveness (22), our results indicate that, unlike murine Fshb, human FSHB transcription is not induced by progestins or androgens in gonadotrope cells. Our results are also in agreement with several studies that reported that testosterone treatment of GnRH-deficient men did not result in increased FSH levels (26–28). Thus, it is unlikely that reduction of FSH levels in men with the −211 G/T SNP is due to a change in steroid responsiveness of the FSHB promoter.

Figure 1.

The human FSHB promoter is not induced by androgen treatment in immortalized gonadotropes. The murine −1000 Fshb-luc, the human −1028 FSHB-luc, or the human −1028 FSHB-luc with a consensus HRE (+ HRE) was transiently transfected into LβT2 cells along with 200 ng of AR. A, After overnight starvation in serum-free media, cells were treated for 24 hours with 0.1% ethanol or 100nM R1881. B, The cells were treated for 24 hours with 0.1% ethanol or 100nM DHT. The results represent the mean ± SEM of 3 (A) or 4 (B) experiments performed in triplicate and are presented as fold androgen induction relative to vehicle. The different uppercase letters indicate that mFshb-luc transcription is significantly different from hFSHB-luc or hFSHB-luc + HRE using a 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference post hoc test.

LHX3 binds to an element in the human FSHB promoter that encompasses the −211 G/T SNP

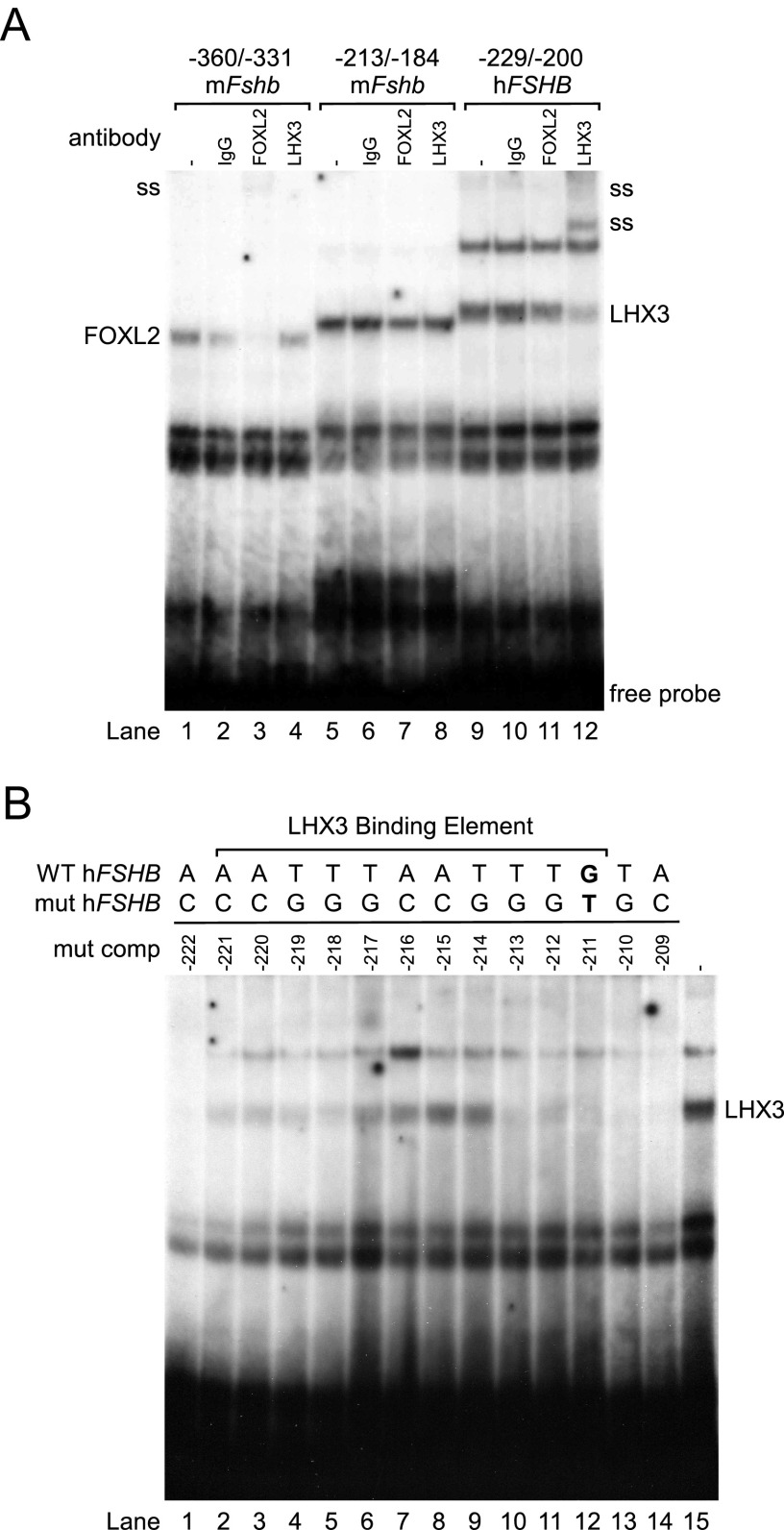

Because the human FSHB promoter is not regulated by androgens or progestins, we sought to identify factors necessary for FSHB transcription that are altered by the −211 G/T mutation. In addition to steroid responsiveness, the −196 nucleotide in the murine Fshb promoter, corresponding to the human −211 nucleotide, is involved in activin induction of Fshb (22). Because this region was suggested to contain a FOXL2 binding element (29), we tested whether this region binds the FOXL2 transcription factor in EMSA. We used a 30-mer oligonucleotide from −360/−331 of the murine Fshb promoter as a positive control for FOXL2 binding because it contains a characterized FOXL2 binding element (29). As previously reported, we showed that LβT2 nuclear extracts formed a protein-DNA complex with the −360/−331 region of the murine Fshb promoter (Figure 2A, lane 1) and that the complex was diminished and supershifted with a FOXL2 antibody (Figure 2A, lane 3), indicating that this complex contains FOXL2. A protein-DNA complex also formed with the −213/−184 region of the murine Fshb promoter (Figure 2A, lane 5) but this complex was not supershifted by the FOXL2 antibody (Figure 2A, lane 7). The protein-DNA complexes formed with the −229/−200 region of the human FSHB promoter were also not shifted with the FOXL2 antibody (Figure 2A, lane 11), indicating that FOXL2 does not bind to this region of the human or murine FSHB promoter. Because the LHX3 homeodomain protein was reported to bind the porcine and human FSHB promoters in this region and regulate basal transcription of FSHB in gonadotropes (30), we tested whether the LHX3 antibody could supershift the protein-DNA complexes. Interestingly, one of the complexes formed with the −229/−200 region of the human FSHB promoter was supershifted by the LHX3 antibody, confirming that LHX3 can bind to this region of the human FSHB promoter. The identity of the protein that binds to the corresponding region of the murine promoter (−213/−184) remains unknown because the protein-DNA complex was not supershifted by the LHX3 antibody.

Figure 2.

The LHX3 homeodomain protein binds to a −221/−211 element in the human FSHB promoter. A, LβT2 nuclear extracts were incubated with a −360/−331 murine Fshb oligonucleotide (oligo) (lanes 1–4), a −213/−184 murine Fshb oligo (lanes 5–8), or a −229/−200 human FSHB oligo (lanes 9–12) and tested for complex formation in EMSA. Protein-DNA complexes are shown, with IgG control (lanes 2, 6, and 10), anti-FOXL2 antibody (lanes 3, 7, and 11), and anti-LHX3 antibody (lanes 4, 8, and 12). Antibody supershifts (ss) are indicated on the left and right. B, LβT2 nuclear extracts were incubated with a −229/−200 human FSHB oligo (lane 15) and tested for complex formation with competition from excess cold oligos containing single base pair mutations ranging from −222 to −209 (lanes 1–14). Abbreviations: WT, wild type; mut, mutant; mut comp, mutant competitor.

Having demonstrated LHX3 binding to the −229/−200 region of the human FSHB, we then determined whether the LHX3 binding element overlaps with the −211 nucleotide using competition with single-nucleotide mutations ranging from −222 to −209. Excess mutant oligonucleotides from −221 to −211 were unable to completely compete with LHX3 binding to the wild-type −229/−200 oligonucleotide (Figure 2B, lanes 2–12). These results indicate that the LHX3 binding site at −221/−211 extends 3 base pairs (bp) past the previously published 8-bp binding element (30) on the 3′ end to include the −211 nucleotide. The additional 3 bp makes the LHX3 binding element in the human FSHB promoter the same length as the LHX3-binding consensus sequence that was defined in vitro by Bridwell et al (31).

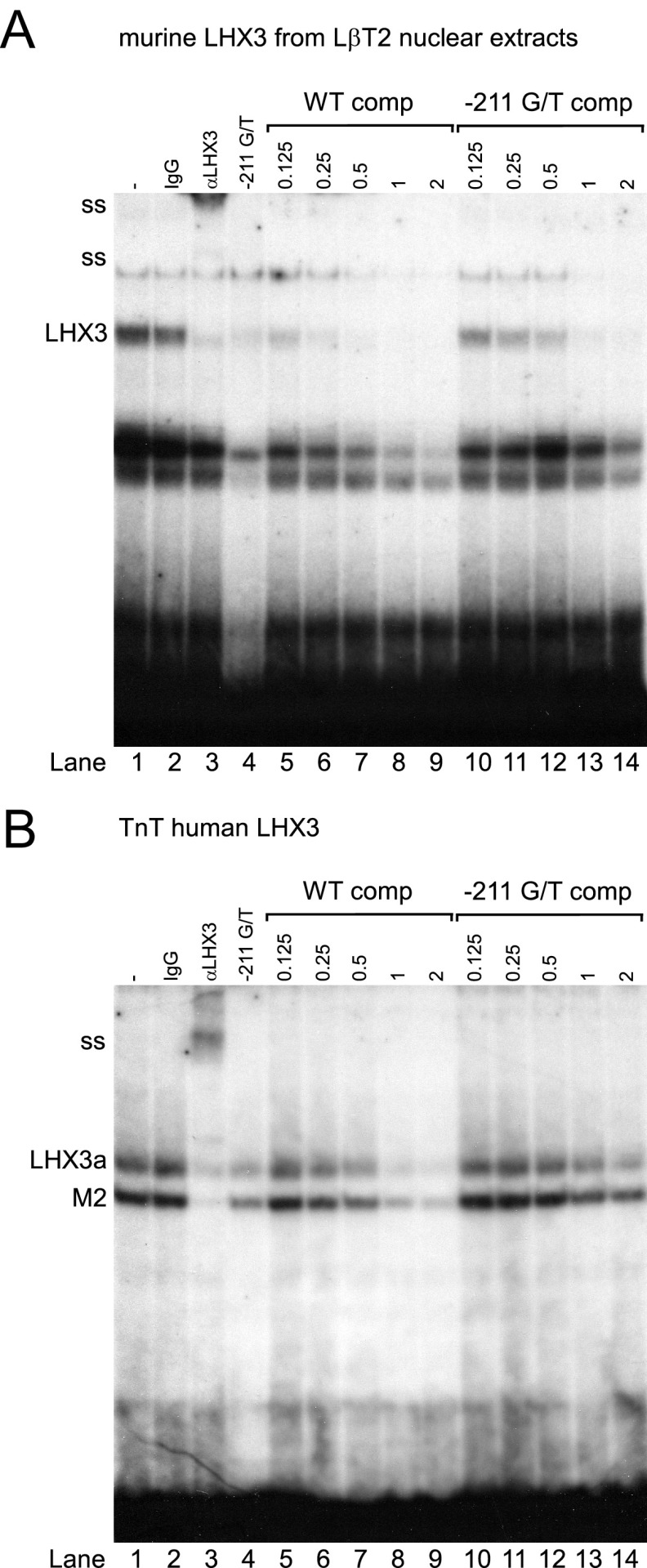

LHX3 binding to the human FSHB promoter is reduced with the −211 G/T SNP

Because the LHX3 binding element on the human FSHB promoter encompasses the −211 SNP, we tested whether binding of LHX3 to the human promoter with the −211 G/T mutation was reduced compared with the wild-type promoter. For these experiments, we used murine LHX3 from LβT2 nuclear extracts as well as a pcDNA3-human LHX3 expression vector to generate in vitro transcribed and translated human LHX3 to determine whether LHX3 binding to the human FSHB promoter was altered by the −211 G/T SNP. The human LHX3 expression vector results in the production of full-length LHX3a as well as a truncated M2 form (32). As shown in Figure 3, murine LHX3, human LHX3a, and M2 bind to the −229/−200 region of the human FSHB promoter (Figure 3, A and B, lane 1). To confirm that the protein-DNA complexes contained LHX3, we supershifted the complexes with the LHX3 antibody (Figure 3, A and B, lane 3) but not with the IgG negative control (Figure 3, A and B, lane 2). Our results demonstrated that LHX3 bound with greater affinity to the wild-type FSHB promoter compared with an oligonucleotide containing the −211 G/T mutation (Figure 3, A and B, lane 1 vs 4). Additionally, we showed that LHX3 binding to the −229/−200 oligonucleotide was more effectively competed with excess wild-type oligonucleotide than with the −211 G/T mutant oligonucleotide (Figure 3A, lane 7 vs 12; Figure 3B, lane 8 vs 13). Collectively, our results support the hypothesis that binding of LHX3 to the human FSHB promoter with the −211 G/T SNP is reduced compared with the wild-type promoter and that decreased LHX3 binding results in reduced FSHB transcription and serum FSH levels. These results also provide supporting evidence that the LHX3 binding element includes the −211 residue because competition with the −211 G/T oligonucleotide is less effective than the wild-type oligonucleotide.

Figure 3.

LHX3 binding to the human FSHB promoter is reduced with the −211 G/T SNP. Nuclear extracts from murine LβT2 cells (A) or in vitro transcribed and translated (TnT) human LHX3 (B) were incubated with a −229/−200 human FSHB oligonucleotide (oligo) (lanes 1–3 and 5–14) or a −211 G/T mutant oligo (lane 4) and tested for complex formation in EMSA. LHX3-DNA complex is shown in lane 1, with the IgG control in lane 2 and the LHX3 supershift (ss) with an anti-LHX3 antibody in lane 3. Competition with 0.125 to 2 pmol of cold, wild-type −229/−200 FSHB oligo (WT comp) or the −211 G/T mutated oligo is shown in lanes 5 to 9 and 10 to 14, respectively. Abbreviations: WT comp, wild-type competitor; comp, competitor.

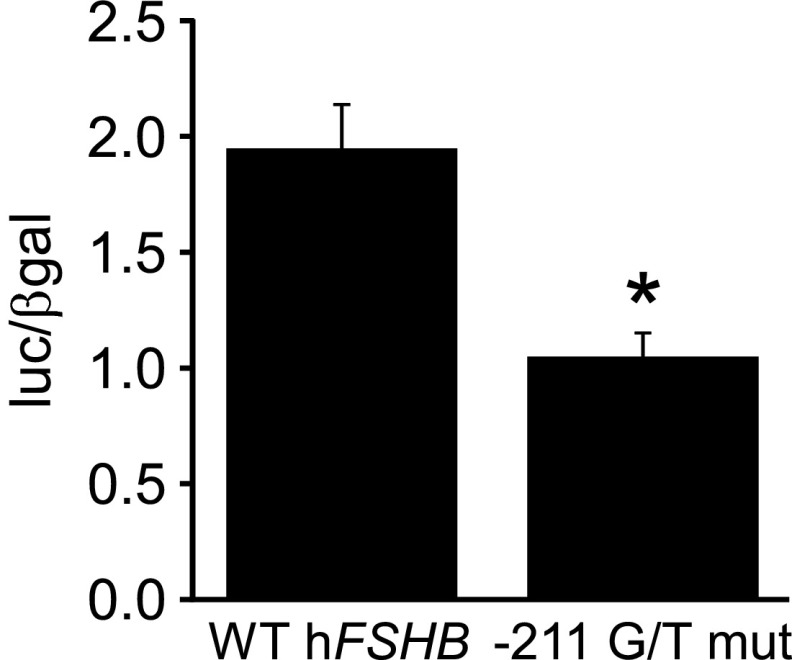

Human FSHB transcription is impaired with the −211 G/T SNP

Although our EMSA data indicated that LHX3 binding to the −211 G/T mutation is reduced compared with the wild-type human FSHB promoter, a connection between decreased LHX3 binding and FSHB transcription has yet to be demonstrated in gonadotrope cells. To test this, we performed transient transfection assays in LβT2 cells to determine whether basal transcription of human FSHB was altered by the −211 G/T mutation compared with the wild-type promoter. As indicated in Figure 4, basal transcription of human FSHB was significantly reduced by approximately 50%. This is a similar amount to what was observed previously in 2 heterologous human cell lines, JEG-3 and TE671 (33). Unlike basal transcription, GnRH induction of FSHB was not altered by the −211 G/T mutation (data not shown).

Figure 4.

FSHB transcription is reduced with the −211 G/T mutation in the human FSHB promoter. The wild-type (WT) human −1028 FSHB-luc and the −211 G/T mutation (mut) were transiently transfected into LβT2 cells, as indicated. The results represent the mean ± SEM of 6 experiments performed in triplicate and are presented as luc/β-gal. *, FSHB-luc transcription is significantly decreased with the −211 G/T mutation compared with the wild-type promoter using Student's t test.

Because a decrease in basal FSHB transcription is observed with the −211 G/T mutation compared with the wild-type human promoter, our studies indicate that the decreased serum FSH levels observed in men with the −211 SNP are probably due to reduced LHX3 binding and regulation of basal FSHB transcription. In one study, men who were homozygotes for the T allele accounted for approximately 25% of infertile men with low FSH levels (16), suggesting that a genetic screen for the −211 G/T SNP may be a useful diagnostic tool for identifying a subset of infertile men who are good candidates for recombinant FSH therapy. Recombinant FSH has been shown to increase sperm counts in infertile men with isolated FSH deficiency (34, 35). It will also be interesting to determine whether there is any association between the −211 G/T SNP and reduced FSH levels and infertility in women, because FSH also plays a critical role in female reproduction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kellie Breen, Danalea Skarra, and Scott Kelley for their suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 HD067448 to V.G.T. This work was also supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/NIH through a cooperative agreement (U54 HD012303) as part of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research and by a University of California, San Diego, Academic Senate Health Sciences Research Grant.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AR

- androgen receptor

- β-gal

- β-galactosidase

- FOXL2

- forkhead box L2

- HRE

- hormone response element

- luc

- luciferase

- SNP

- single-nucleotide polymorphism.

References

- 1. Apter D. Development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;816:9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plant TM, Marshall GR. The functional significance of FSH in spermatogenesis and the control of its secretion in male primates. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:764–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pierce JG, Parsons TF. Glycoprotein hormones: structure and function. Ann Rev Biochem. 1981;50:465–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaiser UB, Jakubowiak A, Steinberger A, Chin WW. Differential effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) pulse frequency on gonadotropin subunit and GnRH receptor messenger ribonucleic acid levels in vitro. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1224–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang Y, Fortin J, Lamba P, et al. Activator protein-1 and smad proteins synergistically regulate human follicle-stimulating hormone β-promoter activity. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5577–5591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindstedt G, Nyström E, Matthews C, Ernest I, Janson PO, Chatterjee K. Follitropin (FSH) deficiency in an infertile male due to FSHβ gene mutation. A syndrome of normal puberty and virilization but underdeveloped testicles with azoospermia, low FSH but high lutropin and normal serum testosterone concentrations. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1998;36:663–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Phillip M, Arbelle JE, Segev Y, Parvari R. Male hypogonadism due to a mutation in the gene for the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1729–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matthews CH, Borgato S, Beck-Peccoz P, et al. Primary amenorrhoea and infertility due to a mutation in the β-subunit of follicle-stimulating hormone. Nat Genet. 1993;5:83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Layman LC, Lee EJ, Peak DB, et al. Delayed puberty and hypogonadism caused by mutations in the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:607–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Layman LC, Porto AL, Xie J, d, et al. FSHβ gene mutations in a female with partial breast development and a male sibling with normal puberty and azoospermia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3702–3707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lofrano-Porto A, Casulari LA, Nascimento PP, et al. Effects of follicle-stimulating hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin on gonadal steroidogenesis in two siblings with a follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit mutation. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:1169–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kottler ML, Chou YY, Chabre O, et al. A new FSHβ mutation in a 29-year-old woman with primary amenorrhea and isolated FSH deficiency: functional characterization and ovarian response to human recombinant FSH. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162:633–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grigorova M, Punab M, Ausmees K, Laan M. FSHB promoter polymorphism within evolutionary conserved element is associated with serum FSH level in men. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2160–2166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grigorova M, Punab M, Zilaitien B, et al. Genetically determined dosage of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) affects male reproductive parameters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1534–E1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mantovani G, Borgato S, Beck-Peccoz P, Romoli R, Borretta G, Persani L. Isolated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) deficiency in a young man with normal virilization who did not have mutations in the FSHβ gene. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:434–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferlin A, Vinanzi C, Selice R, Garolla A, Frigo AC, Foresta C. Toward a pharmacogenetic approach to male infertility: polymorphism of follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit promoter. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1344–1349.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tüttelmann F, Laan M, Grigorova M, Punab M, Sõber S, Gromoll J. Combined effects of the variants FSHB −211G>T and FSHR 2039A>G on male reproductive parameters. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3639–3647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grigorova M, Punab M, Poolamets O, et al. Increased prevalance of the −211 T allele of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) β-subunit promoter polymorphism and lower serum FSH in infertile men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:100–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Webster JC, Pedersen NR, Edwards DP, Beck CA, Miller WL. The 5′-flanking region of the ovine follicle-stimulating hormone-β gene contains six progesterone response elements: three proximal elements are sufficient to increase transcription in the presence of progesterone. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1049–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spady TJ, Shayya R, Thackray VG, Ehrensberger L, Bailey JS, Mellon PL. Androgen regulates FSHβ gene expression in an activin-dependent manner in immortalized gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:925–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thackray VG, McGillivray SM, Mellon PL. Androgens, progestins and glucocorticoids induce follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene expression at the level of the gonadotrope. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2062–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghochani Y, Saini JK, Mellon PL, Thackray VG. FOXL2 is involved in the synergy between activin and progestins on the follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit promoter. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2023–2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ikonen T, Palvimo JJ, Jänne OA. Heterodimerization is mainly responsible for the dominant negative activity of amino-terminally truncated rat androgen receptor forms. FEBS Lett. 1998;430:393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Graham KE, Nusser KD, Low MJ. LβT2 gonadotroph cells secrete follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) in response to activin A. J Endocrinol. 1999;162:R1–R5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pernasetti F, Vasilyev VV, Rosenberg SB, et al. Cell-specific transcriptional regulation of FSHβ by activin and GnRH in the LβT2 pituitary gonadotrope cell model. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2284–2295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sheckter CB, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ. Testosterone administration inhibits gonadotropin secretion by an effect directly on the human pituitary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;68:397–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Finkelstein JS, O'Dea LS, Whitcomb RW, Crowley WF., Jr Sex steroid control of gonadotropin secretion in the human male. II. Effects of estradiol administration in normal and gonadotropin-releasing hormone-deficient men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73:621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winters SJ. FSH is produced by GnRH-deficient men and is suppressed by testosterone. J Androl. 1994;15:216–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corpuz PS, Lindaman LL, Mellon PL, Coss D. FoxL2 is required for activin induction of the mouse and human follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:1037–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. West BE, Parker GE, Savage JJ, et al. Regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone β gene by the LHX3 LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4866–4879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bridwell JA, Price JR, Parker GE, McCutchan Schiller A, Sloop KW, Rhodes SJ. Role of the LIM domains in DNA recognition by the Lhx3 neuroendocrine transcription factor. Gene. 2001;277:239–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sloop KW, Dwyer CJ, Rhodes SJ. An isoform-specific inhibitory domain regulates the LHX3 LIM homeodomain factor holoprotein and the production of a functional alternate translation form. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36311–36319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hoogendoorn B, Coleman SL, Guy CA, et al. Functional analysis of human promoter polymorphisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2249–2254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Al-Ansari AA, Khalil TH, Kelani Y, Mortimer CH. Isolated follicle-stimulating hormone deficiency in men: successful long-term gonadotropin therapy. Fertil Steril. 1984;42:618–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Efesoy O, Cayan S, Akbay E. The efficacy of recombinant human follicle-stimulating hormone in the treatment of various types of male-factor infertility at a single university hospital. J Androl. 2009;30:679–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]