Abstract

Termite hindguts are populated by a dense and diverse community of microbial symbionts working in concert to transform lignocellulosic plant material and derived residues into acetate, to recycle and fix nitrogen, and to remove oxygen. Although much has been learned about the breadth of microbial diversity in the hindgut, the ecophysiological roles of its members is less understood. In this study, we present new information about the ecophysiology of microorganism Diplosphaera colotermitum strain TAV2, an autochthonous member of the Reticulitermes flavipes gut community. An integrated high-throughput approach was used to determine the transcriptomic and proteomic profiles of cells grown under hypoxia (2% O2) or atmospheric (20% O2) concentrations of oxygen. Our results revealed that genes and proteins associated with energy production and utilization, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, nitrogen fixation, and replication and recombination were upregulated under 2% O2. The metabolic map developed for TAV2 indicates that this microorganism may be involved in biological nitrogen fixation, amino-acid production, hemicellulose degradation and consumption of O2 in the termite hindgut. Variation of O2 concentration explained 55.9% of the variance in proteomic profiles, suggesting an adaptive evolution of TAV2 to the hypoxic periphery of the hindgut. Our findings advance the current understanding of microaerophilic microorganisms in the termite gut and expand our understanding of the ecological roles for members of the phylum Verrucomicrobia.

Keywords: termite, microaerophilic, Verrucomicrobia, xylan

Introduction

Termites have long been recognized for their ability to consume lignocellulosic plant material and soil (humus), converting it into substrates (primarily acetate) on which the termite depends for carbon and energy. These social insects are not only important for the global carbon cycling, but also for their biotechnological potential as efficient lignocellulose degraders (Brune, 1998). The success of termite feeding behavior is intimately associated with the presence of a diverse and abundant gut microbial community (Ohkuma and Brune, 2011). In the lower termite, R. flavipes, the complexity of symbiosis spans three domains of life: methane-producing Archaea, cellulolytic Eukarya (protozoa) and Bacteria—all acting cooperatively to degrade lignocellulose, fix/recycle nitrogen and remove oxygen, suggesting a division of metabolic activities among members of the community.

It has been long assumed that prokaryotic residents, in the hypoxic periphery of the termite gut, have the primary role of consuming O2 and maintaining a steep radial gradient of this inwardly diffusing gas resulting in anoxia in the luminal portion of the gut (Brune et al., 1995; Köhler et al., 2012). However, this assumption has recently been challenged by the demonstration of a strong correlation between the O2 consumption rate of extracted guts and the number of protozoans per gut (Wertz and Breznak, 2007b), suggesting a more modest role for bacteria in this process—at least in those termites that possess (putatively ‘strictly' anaerobic) cellulolytic protozoa in their hindguts. Although the relative importance of each group has yet to be resolved, it is reasonable to expect that microbial community members have multiple ecological functions, owing to their ubiquitous presence in different termite species.

Among the domain Bacteria, members of the phylum Verrucomicrobia have been consistently detected in molecular surveys of the 16S rRNA gene targeting the microbial community of various termite species (Hongoh et al., 2003; Nakajima et al., 2005; Berlanga et al., 2011; Rosengaus et al., 2011; Köhler et al., 2012). Despite their ubiquity in higher and lower termite species, their functional role remains elusive. In an effort to understand the ecological functions of this microbial group, we previously isolated and characterized Verrucomicrobia strains from the gut of R. flavipes, including the new species D. colotermitum strain TAV2. We confirmed their autochthonous nature, estimated the population number and unveiled the genomic properties (Isanapong et al., 2012, Wertz et al., 2012), suggesting new ecological roles for Verrucomicrobia within the termite gut.

In this study, we investigate the microaerophilic nature of TAV2 and report on novel ecological functions. We employed comprehensive and integrative transcriptomic and proteomic approaches to: (1) identify genes and proteins being expressed in response to different O2 concentrations; (2) develop an experimentally tested metabolic map for TAV2; and (3) establish the first ecophysiological model for an isolate of the phylum Verrucomicrobia.

Materials and methods

Culture conditions

D. colotermitum strain TAV2 (ATCC BAA-2264, DSMZ 25453) was grown in liquid R2A medium without agar (R2B) with a liquid-to-flask volume ratio of 40%. Four replicate cultures were incubated on an orbital shaker at 200 r.p.m inside a vinyl hypoxic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Glass Lake, MI, USA) fitted with an oxygen sensor and automated controller set for 2% or 20% O2 concentration. These O2 concentrations were selected because 60% of the termite hindgut is hypoxic (4% O2 at the epithelial wall decreasing to anoxia approximately 100 μm inwards; Brune et al., 1995), whereas 20% O2 concentration approximates atmospheric O2 concentrations (20.9% at 1 atm). When cells reached an optical density (OD600) of 0.3 (approximately 8.7 × 107 cells per ml), 400 ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation (17 644 g) for 15 min at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold 50 mM phosphate-buffered saline (10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and 130 mM NaCl), pellets were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. For the transcriptomic analysis, 5 ml of each culture was harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 4 °C and immediately processed for RNA isolation.

Microarray design

The D. colotermitum microarray was designed to represent 4022 genes with coverage of three oligonucleotides per open reading frame. It contained 11 492 specific oligonucleotides (45–62 mer) replicated three times onto a glass slide (MYcroarray, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and 166 oligonucleotides were introduced randomly throughout the slide as internal hybridization controls.

Microarray hybridization

Total RNA was extracted from cells grown under 2% and 20% O2 conditions using the RiboPure bacterial RNA kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), followed by DNase I treatment according to the manufacture's instructions. Transcripts were enriched with the MICROBExpress bacterial mRNA enrichment kit (Ambion) and samples (100 ng) were amplified and converted to anti-sense RNA with the MessageAmp II anti-sense RNA amplification kit. Samples were ethanol precipitated and quality was assessed with the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Fluorescent labeling was performed with either Alexa Flour 555 or Alexa Flour 647 dyes, following instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA). Labeled samples were purified using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA), vacuum dried and stored at −20 °C until hybridization.

Slides were pre-hybridized with buffer containing 5 × Saline-Sodium Phosphate EDTA (SSPE) (0.75 M NaCl, 0.05 M NaH2PO4, 0.005 M EDTA), 1% SDS and 1 mg ml−1 acetylated bovine serum albumin at 50 °C for 45 min and washed twice with 0.025 × SSPE. Labeled samples (2.5 μg) were resuspended in 60 μl of 1 × hybridization buffer (25% SSPE, 25% formamide, 0.05% Tween-20, 0.01 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin) and transferred onto the slides. Single-slide rubber hybridization chambers were incubated in a 50 °C water bath for 16 h, followed by post-hybridization washes with 1 × SSPE for 3 min and subsequently with 0.1 × SSPE at room temperature for 1 min. A total of three technical replicates per biological replicate and respective dye swaps were used. Slides were scanned at a 30-μm resolution using the Genepix 4200 A scanner (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Transcriptomic data analysis

Signal intensities were normalized with the locally weighted scatterplot smoothing algorithm, log2-transformed and filtered using a twofold change cutoff (upper level set at 95% and lower level set at 10%) with the GeneSpring GX 11 software package (Agilent Technologies). Statistical analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed using the Student's t-test with subsequent correction with the Benjamini–Hochberg multiple-hypothesis adjustment (Cui and Churchill, 2003).

Protein extraction

Harvested D. colotermitum 2% O2 and 20% O2 growth samples were barocycled (Pressure Biosciences Inc., South Easton, MA, USA) from ambient (10 s) to 35 kpsi (20 s) for 10 times. RapiGestTM SF (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and dithiothreitol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added to 0.1% and 5 mM concentrations, respectively. Samples were incubated at 60 °C for 30 min with gentle shaking. Proteins were digested using sequencing-grade modified porcine trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and peptide concentration measured according to established protocols (Callister et al., 2006).

Proteomic data analysis

Peptides were analyzed using the Accurate Mass and Time tag proteomics approach (Smith et al., 2002) in combination with a reference peptide database empirically generated for D. colotermitum. For database generation, a pooled D. colotermitum sample was fractionated (50 fractions total) using strong cation exchange high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Each fraction was further separated by reverse phase HPLC coupled to a linear ion trap mass spectrometer (LTQ, ThermoFisher Scientific Corp., San Jose, CA, USA). Mass spectrometry (MS) instrument operating conditions and the HPLC separation method have previously been described (Sowell et al., 2008). MS/MS spectra were analyzed using SEQUEST (Eng et al., 1994) and the TAV2 genome (NCBI accession number ABEA00000000). Preliminary filtering of identified peptides was performed according to previously established criteria (Callister et al., 2006).

Proteome abundance information was obtained by LTQ-Orbitrap MS analysis of peptides separated using reverse phase HPLC. Liquid chromatography (LC)-MS spectra were de-isotoped (Jaitly et al., 2009), mass and elution time features identified, then matched (Monroe et al., 2007) to peptides stored in the reference peptide database filtered to exclude non-tryptic peptides, and peptides having a PeptideProphet probability (Keller et al., 2002) <0.50 (false discovery rate of less than 4% Qian et al., 2005). Matched peptides having a mass error <2 p.p.m. and normalized elution time error <0.06 were retained. Measured arbitrary abundance for a peptide was determined by integrating the area under each LC-MS peak for the detected feature matched to that peptide. Peptide abundances among technical replicates were combined, log2-transformed, normalized and converted to protein abundances with the ZRollup method implemented in DAnTE (Polpitiya et al., 2008). Only proteins with two or more unique peptides were retained for ANOVA analysis (P-values <0.05 and q-values to control the false discovery rate below 0.04 in multiple testing; Storey 2002).

Metabolic reconstruction

A combined list of significantly expressed genes and detected proteins under both O2 conditions was used for pathway prediction and metabolic overview of the strain TAV2 using the Oak Ridge National Laboratory annotation pipeline (http://genome.ornl.gov/microbial/verr/) and the Pathosystems Resource Integration Center genome viewer (http://patricbrc.vbi.vt.edu/).

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Eight differentially expressed genes or proteins were selected for RT-qPCR analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Specific primers were designed with the Oligoanalyzer software (http://www.idtdna.com). Anti-sense RNA samples (5 μg) from the microarray analysis were reversed transcribed with the M-MuLV Taq RT-PCR kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Complementary DNA (10 ng) was added to the SYBR Green master mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) containing forward and reverse primers (150 nM each) and reactions were set according to manufacturer's instructions. Reactions were performed in triplicate for each biological replicate and results were normalized to the expression values of the housekeeping gene gyrB (β subunit of the DNA topoisomerase) to calculate fold induction values according to Livak and Schmittgen (2001). Statistical significance was calculated using the two-tailed Student's t-test.

Results

Confirmation of the microaerophilic phenotype of TAV2

Cells of D. colotermitum strain TAV2 were grown in liquid culture under controlled 2% or 20% O2 concentrations. The growth rate during exponential phase for cells subjected to 2% O2 was 0.0368 h−1, whereas a growth rate of 0.0313 h−1 was calculated for cells grown under 20% O2 concentration (P<0.001). We determined that this difference in growth rates was sufficient to reduce the population doubling time by approximately 4 h for the 2% O2 culture.

Transcriptome analysis

Microarray analysis allowed identification of 75 genes as differentially expressed (P<0.05), with an upregulation of 49 genes and a downregulation of 26 genes, when cells were grown under an atmosphere of 2% O2 as opposed to 20% O2. When differentially expressed genes were classified by functional categories based on clusters of orthologous groups (COGs) (Tatusov et al., 1997), hypothetical genes or proteins of unknown function comprised 42.6% of the data set (Supplementary Table 1). Functional categories representing energy production and conversion, cell cycle control, replication and recombination, and cellular trafficking and secretion were present in the upregulated group for the 2% O2 condition, whereas amino acid transport and metabolism and coenzyme transport were identified as downregulated functional groups.

Proteome analysis

A total of 36 109 peptides were identified in the LC-MS/MS analysis, with 18 044 and 18 065 peptides detected in samples derived from 2% O2- and 20% O2-grown cells, respectively. After data filtering to remove peptide and protein redundancies, 820 and 735 proteins were detected for each environmental condition, respectively. The above values account for 33% (2% O2) and 30% (20% O2), of the protein-coding genes identified in the high draft genome of D. colotermitum. Among identified proteins, 665 (74.7%) were detected in both culture conditions.

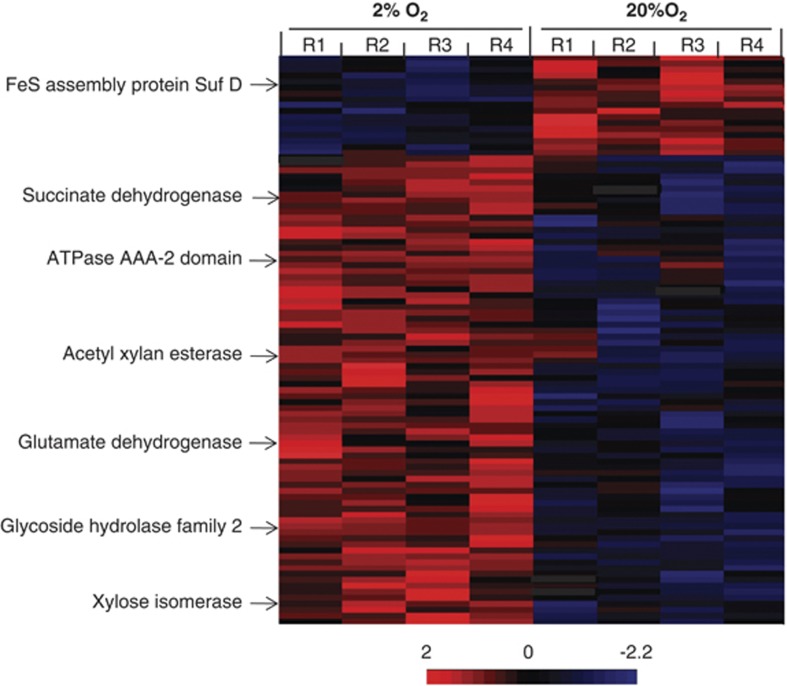

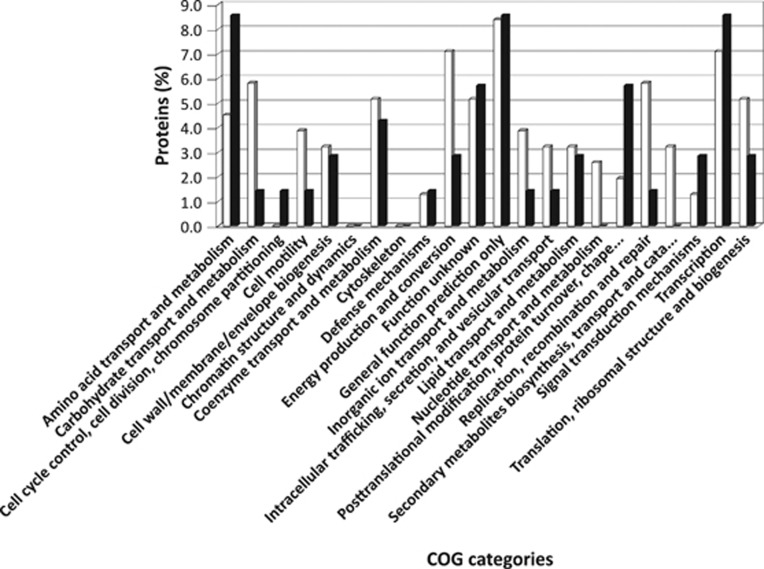

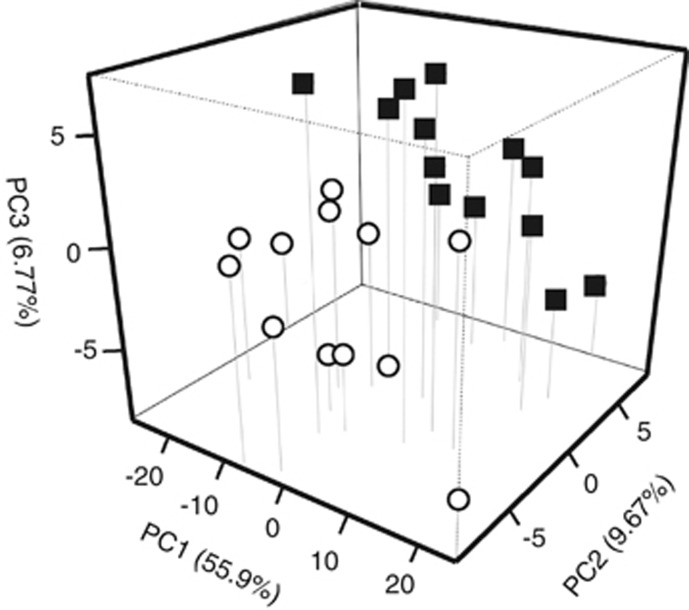

A total of 96 proteins were identified as upregulated (P<0.05), with 79 having higher spectral count measurements under 2% O2, whereas 17 proteins were more abundant in cells growing under 20% O2 concentration (Figure 1). Once assigned to functional categories, conserved hypothetical proteins or proteins encoded by genes previously classified as hypotheticals ranked as the largest group. The relative proportions of proteins classified in these two groups were 27.1% and 37.1% for 2% and 20% O2, respectively. After removal of hypotheticals, the remaining proteins were placed in 22 COG categories in order to describe changes in cellular functions in response to O2 (Figure 2). Eight COG categories had at least a twofold higher protein expression for cells grown under 2% O2 in comparison to those grown under 20% O2 conditions. These included: energy production and conversion (7.1%), carbohydrate transport and metabolism (5.8%), replication and recombination (5.8%). Only three categories had a two times higher protein expression under 20% O2 condition: amino-acid transport and metabolism (8.4%), protein turnover and post-translational modifications (5.7%) and signal transduction mechanisms (2.9%). A principal component analysis of the proteomic results indicated that 72.34% of the variation could be explained by O2 (55.9%), biological (9.67%) and technical (6.77%) replicates (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Heat map comparisons of calculated Z-scores for proteins differentially expressed by TAV2 cells grown under 2% or 20% O2. Increasing intensity in the positive range (red) represents abundances that are greater than the mean abundance derived from both conditions relative to the standard deviation associated with the mean. A few enzymes discussed in the text are illustrated as indicated by the arrows.

Figure 2.

Relative proportions of unique proteins assigned to functional categories based on cluster of orthologous groups (COG). White bars represent proteins detected in cells grown under 2% O2, whereas black bars represent proteins observed in cells grown under 20% O2.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis of the proteome results for TAV2 cells grown under 2% or 20% O2. Components were: (1) O2 concentration, (2) biological replicate and (3) technical replicate. Open circles represent samples of cells grown under 2% O2, whereas closed squares represent cells under 20% O2.

Transcriptomic and proteomic data comparison

We performed separate correlations for transcriptomic and proteomic data. The majority of the genes showed similar expression values in the two conditions tested (R2=0.7909). The selection of differentially expressed genes modified the slope and lowered the coefficient of determination (R2=0.3748). This is consistent with the larger number of genes that were upregulated under 2% O2 in comparison to 20% O2 (Supplementary Figure 1A). When the proteomic data were also examined in a similar manner, peptide abundances for proteins found in both conditions had a coefficient of determination of R2=0.8641. The value was maintained approximately the same (R2=0.8543) when only differentially detected proteins were selected for the calculation (Supplementary Figure 1B).

Next, we compared differentially expressed genes and proteins within the different COG categories. Clusters that had a large number of genes expressed also displayed a larger number of proteins being detected: energy production and conversion, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, and replication and recombination. An agreement between expressed transcripts and their corresponding proteins was only observed for a limited number of genes: ABC transporter, acetyl xylan esterase, ATP synthase, phosphofructokinase, ribosomal proteins, tetratricopeptide-repeat-containing protein, and a type II secretion system protein.

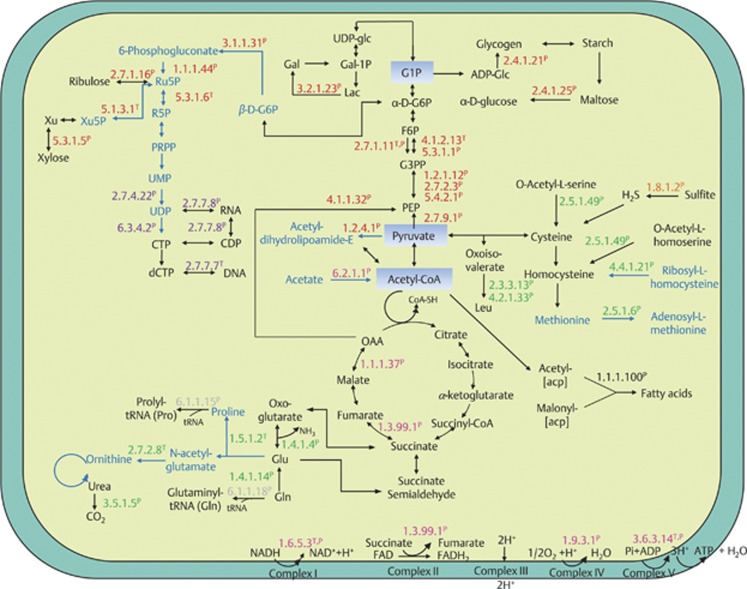

Metabolic reconstruction

We combined differentially expressed genes and proteins to construct a metabolic map for D. colotermitum (Figure 4). Only enzymes assigned with an Enzyme Commission (EC) number were included in the reconstruction to provide an overall picture of TAV2 metabolism and determine the metabolic changes that occur in TAV2 at microoxic and atmospheric O2 concentrations. The following functional categories were used for reconstruction:

Figure 4.

Metabolic map of D. colotermitum strain TAV2 constructed with selected differentially expressed genes and proteins. Proteins (P) and/or their mRNA transcripts (T) are classified into six major metabolic classes: carbohydrate metabolism (red), energy generation (pink), amino-acid biosynthesis (green), nucleotide metabolism (purple), fatty acid synthesis (black) and translation (gray). The enzyme sulfite reductase is shown in orange. Text marked in black represents upregulated pathways under 2% O2, whereas text marked in blue represents downregulated pathways. acp, acyl carrier protein; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ADP-glc, adenosine diphosphoglucose; CTP, cytidine triphosphate; CDP, cytidine diphosphate; dCTP, deoxycytidine triphosphate; Gal-1P, galactose-1-phosphate; Gal, galactose; G1P, glucose-1-phosphate; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; G3PP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; F6P, fructose-6-phosphate; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form); FADH, flavin adenine dincleotide (reduced form); Lac, lactose; Leu, leucine; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized form); NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form); OAA, oxaloacetate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; Ru5P, ribulose 5-phosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; UDP-glc, uridine diphosphate glucose; UMP, uridine monophosphate; UDP, uridine diphosphate.

Carbohydrate metabolism

Two major carbohydrate pathways were derived from the combined data: glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). Eight out of the sixteen enzymes (50%) involved in glycolysis were upregulated under 2% O2. Among these enzymes, a positive correspondence between transcriptomic and proteomic analyses was found for phosphofructokinase (EC: 2.7.1.11T,P; superscript T and P denotes identification through transcriptome or proteome, respectively), the enzyme mediating the most important irreversible step from fructose 6-phosphate to fructose 1,6-bisphosphate. All enzymes associated with the PPP were downregulated under the same condition. It is noteworthy that the enzyme xylose isomerase (E.C.5.3.1.5P) was upregulated. This enzyme is responsible for providing D-xylulose entering the PPP.

Malate dehydrogenase (EC:1.1.1.37P) and succinate dehydrogenase (EC:1.3.99.1P), two enzymes of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, were significantly upregulated under 2% O2 concentration, whereas pyruvate dehydrogenase (acetyl-transferring; EC:1.2.4.1P), the enzyme-mediating glucose catabolism, from glycolysis to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle was downregulated. The former two enzymes have been found to increase their activities under microaerobic growth (Pauling et al., 2001), whereas the latter enzyme has its expression repressed by low levels of O2. Interestingly, the enzyme pyruvate phosphate-dikinase (EC:2.7.9.1P), an important enzyme in reversing glycolysis, was upregulated in cells maintained under microoxic conditions.

Upregulated genes and proteins were searched against the catalytic module of the carbohydrate-active enzyme database. We identified enzymes in four groups, as follows: glycosyl hydrolases (family 2 TIM barrel, 4-α-glucanotransferase (EC:2.4.1.25P)), carbohydrate esterases (acetyl xylan esterase (EC:3.1.1.72P)), glycosyl transferases (glycogen/starch synthase, ADP-glucose type (EC:2.4.1.21P)) and miscellaneous (xylose isomerase (EC:5.3.1.5P)).

Amino acid biosynthesis

Our metabolic reconstruction analysis indicated that strain TAV2 is capable of synthesizing amino acids essential to the termite host (leucine, lysine and tryptophan) and non-essential (alanine, glutamate, glutamine, cysteine and serine) under 2% O2, whereas enzymes involved in the synthesis of proline, ornithine and methionine were downregulated. Noteworthy, both enzymes glutamate dehydrogenase (EC:1.4.1.4P) and glutamate synthase (EC:1.4.1.14P), important for N metabolism, were upregulated; whereas the enzymes involved in the formation of proline, pyrroline-5-carboxylate reductase (EC:1.5.1.2T) and ornithine, acetylglutamate kinase (EC:2.7.2.8T), were downregulated. The presence of an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of ornithine and the upregulated expression of the urease α-subunit domain protein (EC:3.5.1.5P) denotes the importance for N recycling in the termite gut.

Energy transduction

TAV2 expressed several genes encoding for enzymes involved in the electron transport system and ATP synthesis. Enzymes such as NADH dehydrogenase (EC:1.6.5.3T,P), succinate dehydrogenase (EC:1.3.99.1P) and cytochrome c oxidase (EC:1.9.3.1P) were significantly upregulated under microoxic conditions. A higher number of spectral counts was observed for the enzyme cbb3 cytochrome oxidase for cells under 2% O2 in comparison to those under 20% O2. We observed a positive concurrence for the ATP synthase between proteomic and transcriptomic data, with both alpha (F1) and beta (Fo) subunits of this large enzymatic complex (EC 3.6.3.14T,P) significantly upregulated under 2% O2 concentration, indicating that ATP formation is carried out through oxidative phosphorylation. Proteomic results showed a higher number of superoxide dismutase peptides for cells grown in 20% O2 concentration, although this increase was slight and not statistically different from those obtained for samples grown under 2% O2. This is consistent with the view that O2 concentrations higher than those naturally found in the termite hindgut represent an oxidative stress for this microaerophile.

Nucleotide metabolism and post-translational modification

Genes and proteins involved in DNA replication, transcription and translation were highly expressed at 2% O2. TAV2 showed a significant expression of enzymes (above three spectral counts) responsible for syntheses of pyrimidine bases, RNA and DNA. When combining proteomic and transcriptomic data, expressed genes and their detected proteins were observed for a subset of ribosomal proteins (L24P, L9P, S11P and L15T) and aminoacyl-tRNA transferases, such as glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (EC:6.1.1.18P), tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (EC:6.1.1.2P) and lysyl-tRNA synthetase (EC:6.1.1.6T). TAV2 expressed several proteins responsible for proofreading and degradation of mismatched DNA base pairs, such as the DNA mismatch repair protein MutSP, and the exodeoxyribonuclease VII small subunitT. Moreover, we observed the presence of proteins involved in gene regulation such as GreA/GreB family elongation factorP, two component transcriptional regulator LuxR familyP, regulatory proteins LacIT and GntR HTHT, and translational proteins, such as the initiation factor 3P, the protein that attaches the mRNA into 30S ribosome subunit, and the translation elongation factor GP. The cytoplasmatic proteins in charge of protein folding, chaperonin GroELP and chaperonin cpn10P were upregulated under 2% O2 condition.

Secretion and transport systems

Our analysis showed that secretion and transport proteins had significantly higher spectral counts under 2% O2 with significant expression of an ATP-binding cassette protein (ABC transporter), type II secretion system protein and tetratricopeptide-repeat-containing protein in both transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. The strain TAV2 expressed the enzyme SecA wing and scaffoldP, involved in the Sec translocase system. SecA is responsible for hydrolyzing ATP during protein export to the periplasm (Economou and Wickner, 1994). Under 2% O2, TAV2 cells expressed solute-binding protein family 1P and family 3P. These carrier-mediated transport proteins help to increase the rate of solute uptake and accumulate solute inside the cells.

Validation of expressed genes through RT-qPCR

To confirm the transcriptomic results, induction values were calculated for eight selected genes using reverse transcription followed by quantitative PCR analysis. All upregulated genes selected for comparison were confirmed to be expressed at significantly higher levels (Supplementary Table 2). Owing to our particular interest in carbon metabolism, one acetyl xylan esterases (P<0.05) and three xylose isomerases (ObacDRAFT_3012, P<0.01; ObacDRAFT_1973 and ObacDRAFT_0419, P<0.05) that were not observed to be upregulated in our transcriptomic results, but showed ⩾2-fold peptide change were included in this analysis. Upregulated expressions for all four genes were observed when measurements were carried out through RT-qPCR.

Discussion

The results of this study confirm the microaerophilic nature of strain TAV2 (Wertz et al., 2012), with a higher growth rate observed for cells grown under 2% O2 than those grown under 20% O2. The long lag-phase shown for cells grown in 20% O2 suggests the need of an acclimation period and the possibility of cells being under oxidative stress. Similarly, longer lag phases have been observed for the termite gut microaerophile Stenoxybacter acetivorans grown under increasing O2 concentrations (Wertz and Breznak, 2007a). When TAV2 cells are maintained under 2% O2, a condition associated with the physicochemical characteristics of the peripheral zone of the termite hindgut (30 mbar O2; Brune et al., 1995), genes associated with functional categories responsible for energy production and conversion, carbohydrate transport and metabolism, and replication and recombination are upregulated as evidenced in both transcriptomic and proteomic data. It is noteworthy to observe that the COG category cell cycle control showed a divergent pattern between proteomic and transcriptomic approaches. We attribute this difference to the small number of genes (18 or 0.66% of the genome) belonging to cell cycle control in comparison to other categories. Refinements on gene identification and annotation methods will help to mitigate possible differences. In addition, several factors may explain transcriptome and proteome differences, such as post-translational modifications, half-lives of mRNA and proteins, and detection limits for both technologies (Zhang et al., 2010).

TAV2 cells show signs of oxidative stress when grown under 20% O2 condition. First, our proteomic approach detected the presence of peptides derived from superoxide dismutase. This result provides an explanation on how TAV2 manages reactive oxygen species and helps to conciliate our previous experimental work, in which the activity of superoxide dismutase was not observed (Wertz et al., 2012). Second, TAV2 cells promote a shift in protein expression with a substantial increase of categories associated with amino-acid transport and metabolism, protein turnover and post-translational modifications, and signal transduction mechanisms. Specifically, proteins encoded by the sufC- and sufD-like genes in Escherichia coli, and predicted to be an ATPase and a complex-stabilizing protein (Nachin et al., 2001, 2003), respectively, were highly abundant. These proteins are associated with the formation of [Fe-S] clusters and involved in repair during oxidative stress. Considering the importance of the initial microbial colonization of recently hatched termite larvae or frequent trophallactic transfers between individuals (Brune and Ohkuma, 2011), the presence of different mechanisms to cope with reactive oxygen species is an important feature for any termite microaerophile. Adaptations to O2 toxicity might be a widespread attribute in the termite hindgut. Leadbetter and Breznak (1996) showed that methanogens, usually thought to be strict anaerobes, possess catalase activity. It is noteworthy that their isolates were in situ localized as present on or near the hindgut wall.

TAV2 cells employ the glycolytic pathway for processing carbohydrates to pyruvate and exert a tight control over the TCA cycle. The expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase, the enzyme responsible for providing acetyl-CoA to the TCA cycle, was downregulated under 2% O2. Previously, Pauling et al. (2001) demonstrated that Azorhizobium caulinodulans cells exhibit a dramatic increase in NADH/NAD+ ratio when cultures are shifted from aerobic to microaerobic conditions. It is possible that hypoxia in TAV2 also resulted in increase of NADH, a well-known inhibitor of the enzymes pyruvate dehydrogenase, citrate synthase, isocitrate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (Barton, 2004), which slows down the overall activity of the TCA cycle. The adaptive consequence of a slow TCA cycle turnover remains to be investigated in depth for microaerophiles, but it suggests a controlled rate of substrate conversion. We hypothesize this metabolic design might be a consequence of the O2 limitation, preventing NADH and FADH2 from being readily oxidized. This is similar to the strategy used by fermentative bacteria operating a reductive TCA cycle (Ludwig, 2004). Although one might expect that the electron transport system and the ATP synthesis machinery may be affected as well, enzymes such as NADH dehydrogenase, cytochrome c oxidase and ATP synthase alpha (F1) and beta (f0) subunits were highly expressed under the low O2 condition. This is consistent with previously observed increase in ATP formation with decreasing O2 concentrations in other microaerophiles (Bergensen and Turner, 1975; Jackson and Dawes, 1976). Interestingly, Graber and Breznak (2004) observed a high molar ratio conversion for the termite spirochete Treponema primitia without substantial increase in biomass. The authors suggested that this mechanism would prevent overpopulation of the termite hindgut, destabilizing the symbiosis.

One of the well-known features of wood-feeding termites is that their diet is low in combined nitrogen (Potrikus and Breznak, 1981; Brune and Ohkuma, 2011). The TAV2 cell seems to be well adapted to its environment by carrying genes for biosynthesis of 20 of the most common amino acids plus ornithine. Our combined transcriptomic and proteomic data made possible for the identification of gene transcripts and proteins for biosynthesis of eight amino acids. This is a surprising finding considering that the growth medium was selected to elicit a broad metabolic response and contained yeast extract and casamino acids, albeit in low concentrations. The potential for biosynthesis and the expression of genes related to amino-acid formation have been shown for two protozoa endosymbionts (Hongoh et al., 2008a, 2008b) and two co-cultivated termite gut spirochete species (Rosenthal et al., 2011). Previously, Sabree et al. (2012) proposed that the nutrient provisioning in termite–bacterial interaction was altered as the intracellular microorganism Blattabacterium, a symbiont in cockroaches, was replaced by hindgut protozoa and/or bacteria in almost all termite species. The presence of biosynthetic genes for all 20 common amino acids in the TAV2 genome and the subsequent expression of many of these genes suggest an array of possible interactions between the Verrucomicrobia population and its host as well as bacterial and protozoan members of the gut community.

Our proteomic results indicated the presence of specific peptides corresponding to the dinitrogenase reductase (NifH) only when cells were grown with 2% O2, corroborating our previous findings for the presence of nitrogen fixation genes (nif) and growth on N-free medium (Wertz et al., 2012). Finally, the expression of a urea-binding signal peptide protein and the α-subunit of urease may indicate a role for TAV2 in the recycling of uric acid excreted by the host. Previously, Potrikus and Breznak (1981) determined uricolysis to be a process mediated by gut bacteria occurring under anoxic conditions. The possibility that uric acid degradation occurs under microaerophilic conditions remains an interesting aspect of symbiosis, yet to be studied. Taken together, the above results imply that TAV2 can contribute to the nitrogen requirements of the termite. We remain cautious about establishing such a link based on the low Verrucomicrobia population size (1.2 × 103 cells) residing in the hindgut (Köhler et al., 2012; Wertz et al., 2012), but even a small contribution could be important in an N-limited ecosystem.

Lately, a renewed interest in the members of the phylum Verrucomicrobia has arisen because of their potential role in complex polysaccharide degradation (Flint et al., 2012; Martinez-Garcia et al., 2012) and importance in the biogeochemical cycling of carbon (Bergmann et al., 2011; Freitas et al., 2012). Although, we have yet to identify specific conditions allowing strain TAV2 to grow in xylan as a sole C source (Wertz et al., 2012), our integrated approach identified genes and proteins involved in lignocellulose degradation, specifically the enzymes acetyl-xylan esterase, xylan α-1,2-glucuronosidase and xylose isomerase, the later being responsible for converting xylose into xylulose, which enters the PPP (White, 2007). Because much of investigation in termite guts have targeted cellulose degradation through biochemical characterization of host celullases (Watanabe and Tokuda, 2010), gene expression of glycosyl hydrolases by protists (Todaka et al., 2007, 2010), and metagenomic (Warnecke et al., 2007) and proteomic (Burnum et al., 2011) approaches, the understanding of xylan hydrolysis remains virtually unexplored. Our results reveal an important and perhaps compartmentalized, ecological role for the TAV2 population on the debranching of xylan residues. Owing to the heteropolymeric structure of xylans, their degradation requires a coordinated action of a microorganism's transcriptional apparatus and a substantial metabolic investment on the production of many xylanolytic enzymes. We were able to identify different acetyl xylan esterases and xylose isomerases being expressed in TAV2 cells (Supplementary Table 2). It appears that the degradation of the xylans might be a wide-spread function among members of the phylum in different environments. Besides the strain TAV2, which belongs to the class Opitutae, soil isolates from classes Verrucomicrobiae, Spartobacteria and subdivision 3 were obtained with diluted medium containing xylan as a sole C source (Sangwan et al., 2005). Furthermore, experiments on single-cell genomics combined with fluorescently labeled xylan and laminarin in marine and fresh waters yielded Verrucomicrobia genomes particularly enriched in glycoside hydrolases (0.91% of total number of genes) in comparison to other sequenced bacterial genomes (0.2%) (Martinez-Garcia et al., 2012). Together, these independent results not only indicate an important ecological role in biopolymer recycling for the phylum, but also raise new questions on environmental conditions necessary for a coordinated response.

In this study, we asked whether O2 was a relevant factor for the proteomic profile differences observed for strain TAV2. Approximately 55.9% of the variance is explained solely by changes in O2 concentrations, suggesting a strong adaptive evolution of TAV2 within the wall-associated, oxygen-consuming termite gut community. Certainly, the identification of other environmental parameters and their combined effects on cell physiology will increase our understanding of the functional role of this species and other members of the phylum Verrucomicrobia.

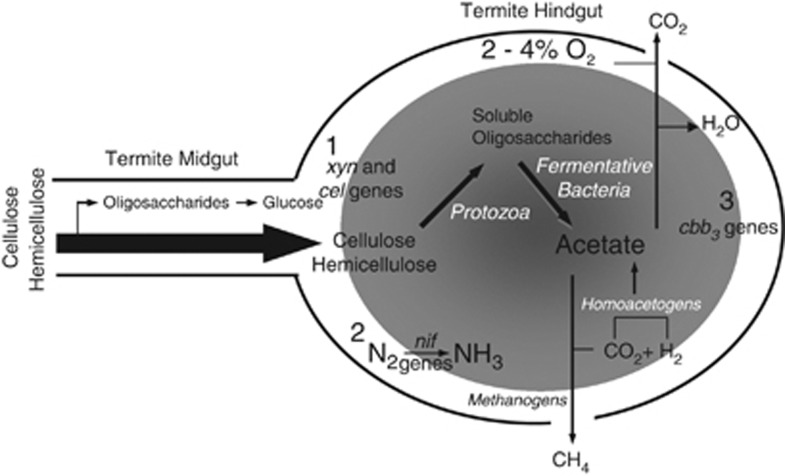

A working model for D. colotermitum strain TAV2 in the R. flavipes hindgut

Our work provides the first integrated omics approach for understanding the ecological role of a member of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. We found that the TAV2 strain can contribute to the metabolism of the R. flavipes gut microbial community through biological N2 fixation, amino-acid production, degradation of xylans and removal of free O2. A conceptual model for the different functions carried out by the D. colotermitum strain TAV2 is proposed in Figure 5. Finally, our results underscore the importance of O2 for whole-genome expression and, ultimately, the physiological state of a cell. Understanding the factors that regulate the microaerophilic physiology will broaden our view of an evolutionarily adapted group, sometimes mistakenly regarded as slow-growing aerobes.

Figure 5.

Model representation of possible functional roles for the D. colotermitum strain TAV2 in the hindgut of the termite R. flavipes. Strain TAV2 expressed genes and/or proteins associated with (1) hemicellulose degradation, (2) biological nitrogen fixation and (3) controlled oxygen consumption. Shaded area represents anoxic core and drawing is not to scale. Other important microbial groups are also represented in the hindgut ecosystem. For detailed morphological descriptions of microorganisms and the termite gut epithelium through transmission electron and scanning electron microscopy see Breznak and Pankratz (1977).

Acknowledgments

A portion of the research was performed using EMSL, a national scientific user facility sponsored by the Department of Energy's Office of Biological and Environmental Research and located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (EMSL 28690). We thank Maeli Melotto and John Breznak for critically reading this manuscript and providing valuable suggestions.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

Supplementary Material

References

- Barton LL. Structural and Functional Relationships in Prokaryotes. Springer: New York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bergensen FJ, Turner GL. Leghaemoglobin and the supply of O2 to nitrogen-fixing root nodule bacteroids: presence of two oxidase systems and ATP production at low free O2 concentration. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;91:345–354. doi: 10.1099/00221287-91-2-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann GT, Bates ST, Eilers KG, Lauber CL, Caporaso JG, Walters WA, et al. The under-recognized dominance of Verrucomicrobia in soil bacterial communities. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga M, Pasteur BJ, Grandcolas P, Guerrero R. Comparison of the gut microbiota from soldier and worker castes of the termite Reticulitermes grassei. Int Microbiol. 2011;14:83–93. doi: 10.2436/20.1501.01.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breznak JA, Pankratz HS. In situ morphology of the gut microbiota of wood-eating termites [Reticulitermes flavipes (Kollar) and Coptotermes formosanus Shiraki] Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:406–426. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.2.406-426.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune A, Emerson D, Breznak JA. The termite gut microflora as an oxygen sink: microelectrode determination of oxygen and pH gradients in lower and higher termites. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2681–2687. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2681-2687.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune A, Ohkuma M.2011Role of the termite gut microbiota in symbiotic digestionIn Bignell DE, Roisin Y, Lo N, (eds).Biology of Termites: a Modern Synthesis Springer: New York, NY; 439–475. [Google Scholar]

- Brune A. Termite guts: the world's smallest bioreactors. Trends Biotechnol. 1998;16:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Burnum KE, Callister SJ, Nicora CD, Purvine SO, Hugenholtz P, Warnecke F, et al. Proteome insights into the symbiotic relationship between a captive colony of Nasutitermes corniger and its hindgut microbiome. ISME J. 2011;5:161–164. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callister SJ, Nicora CD, Zeng XH, Roh JH, Dominguez MA, Tavano CL, et al. Comparison of aerobic and photosynthetic Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1 proteomes. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;67:424–436. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Churchill GA. Statistical tests for differential expression in cDNA microarray experiments. Genome Biol. 2003;4:210. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-4-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou A, Wickner W. SecA promotes preprotein translocation by undergoing ATP-driven cycles of membrane insertion and deinsertion. Cell. 1994;78:835–843. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng JK, Mccomack AL, Yates JR. An approach to correlate tandem mass-spectral data of peptides with amino-acid-sequences in a protein database. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H, Scott K, Duncan S, Louis P, Forano E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:289–306. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas S, Hatosy S, Fuhrman JA, Huse SM, Welsh DBM, et al. Global distribution and diversity of marine Verrucomicrobia. ISME J. 2012;6:1499–1505. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JR, Breznak JA. Physiology and nutrition of Treponema primitia, an H2/CO2-acetogenic spirochete from termite hindguts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1307–1314. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1307-1314.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongoh Y, Ohkuma M, Kudo T. Molecular analysis of bacterial microbiota in the gut of the termite Reticulitermes speratus (Isoptera; Rhinotermitidae) FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2003;44:231–242. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongoh Y, Sharma VK, Prakash T, Noda S, Taylor TD, Kudo T, et al. Complete genome of the uncultured Termite Group 1 bacteria in a single host protist cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008a;105:5555–5560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801389105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongoh Y, Sharma VK, Prakash T, Noda S, Toh H, Taylor TD, et al. Genome of an endoxymbiont compling N2 fixation to cellulolysis within protist cells in the termite gut. Science. 2008b;322:1108–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.1165578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isanapong J, Goodwin L, Bruce D, Chen A, Detter C, Han J, et al. High draft genome sequence of the Opitutaceae bacterium strain TAV1, a symbiont of the wood-feeding termite Reticulitermes flavipes. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:2744–2745. doi: 10.1128/JB.00264-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson FA, Dawes EA. Regulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and poly-β-hydroxybutyrate metabolism in Azotobacter beijerinckii grown under nitrogen or oxygen limitation. J Gen Microbiol. 1976;97:303–312. doi: 10.1099/00221287-97-2-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaitly N, Mayampurath A, Littlefield K, Adkins JN, Anderson GA, Smith RD. Decon2LS: An open-source software package for automated processing and visualization of high resolution mass spectrometry data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:87. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler T, Dietrich C, Scheffrahn RH, Brune A. High-resolution analysis of gut environment and bacterial microbiota reveals functional compartmentation of the gut in wood-feeding higher termites (Nasutitermes spp.) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:4691–4701. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00683-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbetter JR, Breznak JA. Physiological ecology of Methanobrevibacter cuticularis sp. nov. and Methanobrevibacter curvatus sp. nov., isolated from the hindgut of the termite Reticulitermes flavipes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3620–3631. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3620-3631.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig RA. Microaerophilic bacteria transduce energy via oxidative metabolic gearing. Res Microbiol. 2004;155:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Garcia M, Brazel DM, Swan BK, Arnosti C, Chain PSG, Reitenga KG, et al. Capturing single cell genomes of active polysaccharide degraders: an unexpected contribution of Verrucomicrobia. PLoS One. 2012;4:e353144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe ME, Tolic N, Jaitly N, Shaw JL, Adkins JN, Smith RD. VIPER: an advanced software package to support high-throughput LC-MS peptide identification. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2021–2023. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachin L, Hassouni ME, Loiseau L, Expert D, Barras F. SoxR-dependent response to oxidative stress and virulence of Erwinia chrysanthemi: the key role of SufC, an orphan ABC ATPase. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:960–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachin L, Loiseau L, Expert D, Barras F. SufC: an unorthodox cytoplasmic ABC/ATPase required for [Fe-S] biogenesis under oxidative stress. EMBO J. 2003;22:427–437. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Hongh Y, Usami R, Kudo T, Ohkuma M. Spatial distribution of bacterial phylotypes in the gut of the termite Reticulitermes speratus and the bacterial community colonizing the gut epithelium. FEMS Microb Ecol. 2005;54:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuma M, Brune A.2011Diversity, structure, and evolution of the termite gut microbial communityIn Bignell DE, Roisin Y, Lo N, (eds).Biology of Termites: a Modern Synthesis Springer: New York, NY; 413–438. [Google Scholar]

- Pauling DC, Paris CA, Ludwig RA. Azorhizobium caulinodans pyruvate dehydrogenase activity is dispensable for aerobic but required for microaerobic growth. Microbiology. 2001;147:2233–2245. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-8-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polpitiya AD, Qian WJ, Jaitly N, Petyuk VA, Adkins JN, Camp DG, et al. DAnTE: a statistical tool for quantitative analysis of -omics data. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1556–1558. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potrikus CJ, Breznak JA. Gut bacteria recycle uric acid nitrogen in termites: a strategy for nutrient conservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4601–4605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian WJ, Liu T, Monroe ME, Strittmatter EF, Jacobs JM, Kangas LJ, et al. Probability-based evaluation of peptide and protein identifications from tandem mass spectrometry and SEQUEST analysis: The human proteome. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:53–62. doi: 10.1021/pr0498638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengaus RB, Zecher CN, Shultheis KF, Brucker RM, Bordenstein SR. Disruption of the termite gut microbiota and its prolonged consequences for fitness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4303–4312. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01886-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal AZ, Matson EG, Eldar A, Leadbetter JR. RNA-seq reveals comperative metabolic interactions between two termite-gut spirochete species in co-culture. ISME J. 2011;5:1133–1142. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabree ZL, Huang CY, Arakawa G, Tokuda G, Lo N, Watanabe H, et al. Genome shrinkage and loss of nutrient-providing potential in the obligate symbiont of the primitive termite Mastotermes darwiniensis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:204–210. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangwan P, Kovac S, Davis KER, Sait M, Janssen PH. Detection and cultivation of soil Verrucomicrobia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8402–8410. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8402-8410.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Anderson GA, Lipton MS, Pasa-Tolic L, Shen YF, Conrads TP, et al. An accurate mass tag strategy for quantitative and high-throughput proteome measurements. Proteomics. 2002;2:513–523. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200205)2:5<513::AID-PROT513>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell SM, Norbeck AD, Lipton MS, Nicora CD, Callister SJ, Smith RD, et al. Proteomic analysis of stationary phase in the marine bacterium ‘Candidatus Pelagibacter ubique'. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:4091–4100. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00599-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey D. A direct approach to false discovery rates. J Royal Stat Soc S B. 2002;64:479–498. [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaka N, Inoue T, Saita K, Ohkuma M, Nalepa CA, Lenz M, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of cellulolytic enzyme genes from representative lineages of termites and a related cockroach. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8636. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaka N, Moriya S, Saita K, Hondo T, Kiuchi I, Takasu H, et al. Environmental cDNA analysis of the genes involved in lignocellulose digestion in the symbiotic protist community of Reticulitermes speratus. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;59:592–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnecke F, Luginbuhl P, Ivanova N, Ghassemian M, Richardson TH, Stege JT, et al. Metagenomic and functional analysis of hindgut microbiota of a wood-feeding higher termite. Nature. 2007;450:560–570. doi: 10.1038/nature06269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H, Tokuda G. Cellulolytic systems in insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 2010;55:609–632. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz JT, Breznak JA. Stenoxybacter acetivorans gen. nov., an acetate-oxidizing obligate microaerophile among diverse O2-consuming bacteria from termite guts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007a;73:6819–6828. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00786-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz JT, Breznak JA. Physiological ecology of Stenoxybacter acetivorans, an obligate microaerophile in termite guts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007b;73:6829–6841. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00787-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz JT, Kim E, Breznak JA, Schmidt TM, Rodrigues JLM. Genomic and physiological characterization of the Verrucomicrobia isolate Diplosphaera colotermitum gen. nov., sp. nov., reveals microaerophily and nitrogen fixation genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:1544–1555. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06466-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White D. The Physiology and Biochemistry of Prokaryotes. Oxford University Press: New York; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Li F, Nei L. Integrating multiple ‘omics' analysis for microbial biology: application and methodologies. Microbiology. 2010;156 ((Pt 2:287–301. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.