Abstract

Sugarcane is the most important sugar and bioenergy crop in the world. The selection and combination of parents for crossing rely on an understanding of their genetic structures and molecular diversity. In the present study, 115 sugarcane genotypes used for parental crossing were genotyped based on five genomic simple sequence repeat marker (gSSR) loci and 88 polymorphic alleles of loci (100%) as detected by capillary electrophoresis. The values of genetic diversity parameters across the populations indicate that the genetic variation intrapopulation (90.5%) was much larger than that of interpopulation (9.5%). Cluster analysis revealed that there were three groups termed as groups I, II, and III within the 115 genotypes. The genotypes released by each breeding programme showed closer genetic relationships, except the YC series released by Hainan sugarcane breeding station. Using principle component analysis (PCA), the first and second principal components accounted for a cumulative 76% of the total variances, in which 43% were for common parents and 33% were for new parents, respectively. The knowledge obtained in this study should be useful to future breeding programs for increasing genetic diversity of sugarcane varieties and cultivars to meet the demand of sugarcane cultivation for sugar and bioenergy use.

1. Introduction

Sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) is the main sugar and bioenergy crop in the world. In comparison to other countries, Chinese sugar consumption is much lower and has only about 1/3 average of the world due to the different diet. However, the total sugar consumption, production, and import are in the second, third, and first positions in the world in recent years [1]. In addition, sugar from sugarcane occupies about 90%–92% of the total sugar output in China [2]. With an increasing demand for sugar, sugarcane shows more potential in China, leading to over one million sugarcane seedlings cultivated, which are produced from a total of 600–700 cross combinations every year in China [1]. The security of sugarcane cultivation is under threat from a number of diseases, especially smut disease caused by Sporisorium scitamineum and mosaic disease caused by sugarcane mosaic virus or sorghum mosaic virus. This leads to a demand for heterogeneity of cultivars. However, the heterogeneity of cultivars remains low, since the three “ROC” serial varieties account for about 85% of the total sugarcane cultivated area in China, with one (ROC22) responsible for about 50%–60% of the cultivated area in the last ten years [1]. Cross breeding is the most important way for breeding new sugarcane varieties and variety improvement, and it has played a significant role in the development of sugar industries in almost all the sugarcane-producing countries [3]. In addition, parental crosses of sugarcane always improve significantly the cane stalk yield and sugar content; thus, it is important to get the understanding of the genetic diversity of parents for crosses in breeding programs in China.

Traditional ways for sugarcane breeders to identify the relationships among varieties rely on anatomical and morphological characters [4]. In recent years, genetic diversity has been investigated for sugarcane cultivars or ancestral species by using several molecular methods, such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) [5, 6], random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [7, 8], amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) [9], intersimple sequence repeats (ISSR) [10, 11], sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) [12, 13], target region amplification polymorphism (TRAP) [14, 15], genomic in situ hybridization (GISH) [16, 17], fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) [17–19], genomic simple sequence repeats (gSSR, hereinafter referred to as SSR) [9], and expressed sequence tag-SSR (EST-SSR) markers [20]. Among all the above molecular techniques, SSR markers are widely used in the genetic diversity analysis of sugarcane because they are codominantly inherited, abundant, and highly reproducible [20–22]. Cordeiro et al. (2003) used six gSSR markers to assess the genetic diversity level between the 66 accessions which included the genera Saccharum (S. officinarum, S. spontaneum, and S. sinense), Old World Erianthus Michx. sect. Ripidium, North American E. giganteus (S. giganteum), Sorghum, and Miscanthus [23]. Liu et al. (2011) and Pan (2010) used polymorphic SSR DNA markers to genotype sugarcane clones with a fluorescence electrophoresis (CE)-based genotyping system [24, 25]. A few studies have also been reported on the genetic diversity of sugarcane parental accessions by SSR markers [26, 27].

Some accessions have played a particular key role in the development of commercial sugarcane varieties and thus have been designed as common breeding parents [28, 29]. In addition, new parental materials are more important for broadening genetic basis in the development of modern varieties used for cultivation and breeding [30, 31]. Therefore, investigation of the genetic relationships among common and new parental accessions is necessary for future sugarcane improvement and breeding in China.

In sugarcane breeding programmes, the choice of parents for crossing largely depends on the aims and objectives of the breeder. In the past, this was generally based on phenotypic and genotypic expression of the characters they display and especially on the superior progeny, that is, the potential ability of cane sugar yield of varieties derived from the cross combinations, which is also influenced by the environment and a series of uncontrolled factors. The objective of the present study is to evaluate the genetic diversity of 115 sugarcane cross parents, termed as common or new parents, using SSR markers. For the molecular analysis, two levels of analysis were investigated. Firstly, the within and between population diversity was evaluated on 64 common parents and 51 new parents, each represented by different groups, and the genetic parameters between the two groups of accessions were analyzed, respectively. Secondly, cluster analysis by unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) and principle component analysis (PCA) of 115 parents was performed. The information obtained in this study will be valuable for choice of parents and cross prediction and especially for the development of cultivar improvement programs in modern sugarcane breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The background of the sugarcane parents used in this study was given in Table 1. Leaf samples of a total of 115 sugarcane accessions, including 64 common parents and 51 new parents, were collected. They were cultivated in Sugarcane Resources Nursery of FAFU (Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China) and Ruili Breeding Station in Yunnan Academy of Agriculture Science (Ruili, Yunnan, China).

Table 1.

Description of the 115 sugarcane (Saccharum complex) accessions used in the SSR study.

| Code | Name of accession | Collection place | Code | Name of accession | Collection place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GT86-267 | FAFU | 59 | CP65-357 | FAFU |

| 2 | GT89-5 | FAFU | 60 | CP67-412 | FAFU |

| 3 | GT93-103 | FAFU | 61 | CP72-1210 | FAFU |

| 4 | GT94-116 | FAFU | 62 | CP72-1312 | FAFU |

| 5 | GT94-119 | FAFU | 63 | CP84-1198 | FAFU |

| 6 | GT96-44 | FAFU | 64 | CP85-1308 | Ruili |

| 7 | GT96-211 | FAFU | 65 | *CP88-1762 | FAFU |

| 8 | GT73-167 | Ruili | 66 | *CP89-1509 | FAFU |

| 9 | *GT89-7 | FAFU | 67 | *CP92-1167 | FAFU |

| 10 | *GT90-55 | FAFU | 68 | ROC1 | FAFU |

| 11 | *GT94-119 | FAFU | 69 | ROC10 | Ruili |

| 12 | *GT95-53 | FAFU | 70 | ROC11 | Ruili |

| 13 | *GF97-18 | FAFU | 71 | ROC16 | FAFU |

| 14 | YT96-835 | FAFU | 72 | ROC20 | Ruili |

| 15 | YT96-86 | FAFU | 73 | ROC22 | Ruili |

| 16 | YT00-236 | FAFU | 74 | ROC24 | FAFU |

| 17 | YT85-633 | Ruili | 75 | ROC25 | Ruili |

| 18 | YT91-967 | Ruili | 76 | ROC26 | FAFU |

| 19 | YT93-159 | Ruili | 77 | *ROC2 | FAFU |

| 20 | YT85-177 | Ruili | 78 | *ROC7 | FAFU |

| 21 | *YT82-882 | FAFU | 79 | *ROC18 | FAFU |

| 22 | *YT89-240 | Ruili | 80 | F134 | Ruili |

| 23 | *YT91-854 | FAFU | 81 | *DZ93-88 | Ruili |

| 24 | *YT91-1102 | FAFU | 82 | *DZ93-94 | Ruili |

| 25 | *YT96-244 | FAFU | 83 | *DZ99-36 | Ruili |

| 26 | *YT97-40 | FAFU | 84 | YZ89-351 | FAFU |

| 27 | YC71-374 | FAFU | 85 | YZ94-375 | Ruili |

| 28 | YC82-96 | FAFU | 86 | *YZ92-19 | FAFU |

| 29 | YC82-108 | FAFU | 87 | *YZ99-91 | FAFU |

| 30 | YC84-125 | FAFU | 88 | *Q170 | FAFU |

| 31 | YC89-46 | FAFU | 89 | *Q171 | FAFU |

| 32 | YC90-3 | FAFU | 90 | *Q182 | FAFU |

| 33 | YC90-33 | FAFU | 91 | *CZ89-103 | Ruili |

| 34 | YC92-27 | FAFU | 92 | CZ19 | FAFU |

| 35 | YC96-48 | FAFU | 93 | *CN85-78 | FAFU |

| 36 | *YC90-31 | FAFU | 94 | ZZ74-141 | FAFU |

| 37 | FN91-3623 | FAFU | 95 | ZZ92-126 | FAFU |

| 38 | FN91-4621 | FAFU | 96 | POJ2878 | FAFU |

| 39 | FN91-4710 | FAFU | 97 | Co1001 | FAFU |

| 40 | *FN81-475 | FAFU | 98 | RB72-454 | Ruili |

| 41 | *FN93-3608 | FAFU | 99 | K5 | FAFU |

| 42 | *FN94-0744 | FAFU | 100 | GZ8 | FAFU |

| 43 | *FN02-3924 | FAFU | 101 | LCP85-384 | FAFU |

| 44 | MT86-05 | FAFU | 102 | *Nagori | Ruili |

| 45 | MT86-2121 | Ruili | 103 | *muck che | Ruili |

| 46 | MT90-55 | FAFU | 104 | *laica82-1729 | Ruili |

| 47 | MT92-649 | FAFU | 105 | *YG94-39 | FAFU |

| 48 | *MT69-421 | Ruili | 106 | *RF93-244 | FAFU |

| 49 | *MT92-505 | FAFU | 107 | *Brazil45 | FAFU |

| 50 | *MT93-246 | FAFU | 108 | *FR93-435 | FAFU |

| 51 | *MT96-6016 | FAFU | 109 | *MEX105 | FAFU |

| 52 | HoCP91-555 | FAFU | 110 | *YZ99-601 | FAFU |

| 53 | HoCP93-746 | Ruili | 111 | *K16 | FAFU |

| 54 | HoCP93-750 | FAFU | 112 | *B9 | FAFU |

| 55 | HoCP95-998 | Ruili | 113 | *PS45 | Ruili |

| 56 | YN73-204 | FAFU | 114 | *LY97-151 | Ruili |

| 57 | *YN89-525 | FAFU | 115 | *GN95-108 | FAFU |

| 58 | CP49-50 | FAFU |

Sugarcane Resources Nursery of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (FAFU); Ruili Breeding Station in Yunnan Academy of Agriculture Science (Ruili); *represents new parents.

2.2. DNA Extraction

DNA extractions from the leaf tissues were conducted according to biospin plant genomic DNA extraction kit specification (Bioflux, Japan). Each leaf sample was collected from three independent sugarcane plants and only +1 leaf from each plant. After detection of the quality and concentration, this batch of genomic DNA was diluted to a suitable concentration and stored at −20°C.

2.3. SSR Analysis

A total of five highly polymorphic SSR DNA markers (SMC334BS, SMC336BS, SMC36BUQ, SMC286CS, and SMC569CS) were selected from 221 ICSB sugarcane SSR markers [24, 32]. Forward primers of all these SSR primers were labeled with FAM, the fluorescence dye. PCR amplification was performed in a 25 μL reaction containing 50 ng of genomic DNA, 2.5 μL 10 × PCR buffer, 0.2 μM of each primer, 200 μM dNTP mixtures, and 1.0 U of rTaq polymerase. PCR comprised the following steps: the first cycle was preceded by a 3 min denaturation at 94°C, then thirty-one PCR cycles were performed in a PCR amplifier (Eppendorf 5333), with each cycle consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at either 58°C, 60°C, 62°C, or 64°C for 30 s (SMC286CS, SMC334BS, SMC569CS, and SMC36BUQ) and 62°C for 35 s (SMC336BS), and extension at 72°C for 30 or 35 s, and the last cycle was followed by a 2 min final extension at 72°C. Fragment analyses of amplified PCR products were conducted by capillary electrophoresis (CE) on ABI PRISM 377-96 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each CE sample included 1.0 μL post-PCR reaction mixture, 0.5 μL of ROX-360 size standards, and 8.5 μL loading buffer of which the major ingredient contained polyacrylamide and dextran-blue. Then, PCR-amplified SSR DNA fragments were separated, and both the size standard and PCR amplified fragments were recorded automatically into individual GeneScan files.

2.4. Data Analyses

The data obtained from GeneScan files were analyzed with GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems) to produce capillary electropherograms of amplified DNA fragments. GeneMapper parameters were set as follows: plate check module: Plate Check A; prerun module: GS PR36A-2400; run module: GS run 36A-2400; collect time: 2.5 h; and lanes: 64. An SSR allele or peak was scored either as present (1) or absent (0), except for “stutters,” “pull-ups,” “dinosaur tails,” or “minus adenine” [24, 32]. The polymorphic information content (PIC) was calculated by the formula PIC = 1 − ∑P i 2, where P i is the frequency of the population carrying the ith allele, counted for each SSR locus [21]. Then, the binary data matrices were used for genetic diversity parameter analysis. POPGENE 1.31 [33] was used to determine number of polymorphic bands (NPB); percentage of polymorphic bands (PPB); observed number of alleles (Na); and effective number of alleles (Ne). Nei's genetic diversity (h), mean values of total gene diversity (Ht), and Shannon's information index (I) were computed for each population based on allele frequencies and calculated for haploid data. In addition, gene diversity within populations (Hs), gene diversity between populations (Dst) by the formula (Dst = Ht − Hs), gene differentiation coefficient (Gst) calculated as (Ht − Hs)/Ht, and estimates of gene flow (Nm) were obtained by (1 − Gst)/2Gst. Based on Nei's (1978) genetic distances, a dendrogram showing the genetic relationships between genotypes was constructed by the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic average (UPGMA) using the NTSYS-pc version 2.1 [34, 35]. To further assess the genetic relationships between all of the accessions (9 series), PCA was performed based on genetic similarity using NTSYS-pc version 2.1 [35].

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. SSR Markers

SSR markers were utilized to assess genetic diversity among all the 115 sugarcane parental accessions in this study, and the major values of genetic diversity parameters derived were showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

The allele detection results of 5 SSR markers used for evaluation of 115 sugarcane accessions.

| Primer name | Number of alleles | Number of rare alleles | Range of allele size (bp) | Major allele | PIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (bp) | Frequency (%) | |||||

| SMC334BS | 19 | 6 | 136–169 | 147 | 66.10 | 0.889 |

| SMC336BS | 26 | 15 | 136–192 | 168 | 59.10 | 0.897 |

| SMC36BUQ | 11 | 8 | 101–147 | 122 | 39.10 | 0.753 |

| SMC286CS | 15 | 6 | 123–169 | 146 | 46.10 | 0.865 |

| SMC569CS | 17 | 11 | 159–238 | 220 | 66.10 | 0.779 |

|

| ||||||

| Average | 17.6 | 9.2 | 0.837 | |||

Rare allele means that the frequency of the allele is less than 5.0%; the major allele accounts for the highest proportion in all alleles.

A total of five SSR loci were used to evaluate 115 sugarcane accessions. Distinct fragments in the size ranging from 101 bp to 238 bp were scored for analysis. The major allele of five SSR loci was observed at the sizes of 147 bp, 168 bp, 122 bp, 146 bp, and 220 bp, with the ratio of 66.1%, 59.1%, 39.1%, 46.1%, and 66.1% with the primers SMC334BS, SMC336BS, SMC36BUQ, SMC286CS, and SMC569CS, respectively. A total of 88 alleles within the data set were obtained, and alleles per locus ranged from 11 to 26, with an average of 17.6. The average number of rare alleles produced in a single individual was 9.2 (range 6–15). The highest number of alleles was scored at locus SMC336BS (26 alleles). The PIC values of five SSR loci ranged from 0.753 to 0.897 with a mean value of 0.837. The PIC value of the SMC336BS locus was the highest (0.897), while the lowest (0.753) was observed from SMC36BUQ locus.

3.2. Genetic Diversity among 64 Common Parents, 51 New Parents, and All 115 Parents

Significant genetic variation was found among all 115 parents with the genetic similarity (GS) value ranging from 0.725 to 1.000. The GS value ranged from 0.730 to 1.000 within the group of 64 common parents and from 0.722 to 0.943 within the group of 51 new parents. Of note, the GS value was 1.000 between MT90-55 and HoCP93-750, indicating that there was no genetic dissimilarity between the two parents based on the five SSR loci.

Genetic parameters for the five microsatellite loci in the two groups, common parents and new parents, were given in Table 3. A total of 88 polymorphic bands within the entire data set were scored, while taking the two groups considered separately, 82 of them were within the 64 common parents (93.18%), and 69 of them were within the 51 new parents (78.41%). Observed numbers of alleles (Na) were the same (2.000) in the two groups, and effective numbers of alleles (Ne) were higher in new parents group (1.359) than in common parents group (1.302). Nei's gene diversity (h) was 0.178, and Shannon's information index (I) was 0.288 in the overall sugarcane testing accessions. In contrast to the total diversity, both sugarcane parent groups of common parents and new parents had relatively high diversity, h = 0.190 and 0.223 and I = 0.308 and 0.356, respectively.

Table 3.

The values of genetic diversity parameters for sugarcane accessions of common and new parents in different groups, estimated based on polymorphisms of 5 SSR loci.

| Group | Clones size | NPB | PPB (%) | Na | Ne | h | I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common parents | 64 | 82 | 93.18 | 2.000 | 1.302 | 0.190 | 0.308 |

| New parents | 51 | 69 | 78.41 | 2.000 | 1.359 | 0.223 | 0.356 |

| Total | 115 | 88 | 100.0 | 2.000 | 1.283 | 0.178 | 0.288 |

Number of polymorphic bands (NPB); percentage of polymorphic bands (PPB); observed number of alleles (Na); effective number of alleles (Ne); Nei's genetic diversity (h); Shannon's information index (I).

Table 4 summarized the genetic differentiation of sugarcane accessions from the two groups. The values of Ht and Dst were higher in new parents group (Ht = 0.214, Dst = 0.058) than those in common parents group (Ht = 0.190, Dst = 0.032), while the value of genetic diversity (Hs) within population was similar in two groups (0.158 for common parents group and 0.156 for new parents group), indicating that the genetic diversity of these two groups mainly existed within populations. The gene flow index (Nm) within groups showed that low gene flow (2.429 and 1.335, resp.) occurred in both groups, while the Gst was high in both groups—0.171 and 0.273, respectively. The gene flow between the two groups was much higher (Nm = 4.762) than those in both groups. This also indicated that the genetic variation mainly existed within populations.

Table 4.

Genetic diversity and differentiation of sugarcane accessions between common and new parents, estimated by POPGENE (version 1.31).

| Group | Clones size | Ht | Hs | Dst | Gst | Nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common parents | 64 | 0.190 | 0.158 | 0.032 | 0.171 | 2.429 |

| New parents | 51 | 0.214 | 0.156 | 0.058 | 0.273 | 1.335 |

| Total | 115 | 0.176 | 0.159 | 0.017 | 0.095 | 4.762 |

Mean values of total gene diversity (Ht), gene diversity within populations (Hs), gene diversity between populations (Dst), gene differentiation coefficient (Gst), and estimates of gene flow from Gst (Nm) were obtained by (1 − Gst)/2Gst.

3.3. Genetic Relationships of 115 Sugarcane Parents

Nine series from 115 accessions sorted by institution-based breeding programme are shown in Table 5. According to the information indicated in Table 1, we assigned them as the following nine series: GT series (13) from Guangxi Sugarcane Institute; YT series (13) from Guangzhou Institute of Sugarcane and Sugar Industry; YC series (10) from Hainan Sugarcane Breeding Station; FN series (7) from Sugarcane Research Institute of FAFU; MT series (7) from Sugarcane Research Institute, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences; HoCP series (4) from Sugarcane Research Unit, Houma, Louisiana, United States Department of Agriculture, USA; CP series (10) from Sugarcane Experiment Station, Canal Point, Florida, United States Department of Agriculture, USA; and “ROC” series (13) from Taiwan Sugar Corporation. The rest of the sugarcane parents included 37 accessions from several breeding institutions different from all the above eight and were termed as OTHER.

Table 5.

Genetic diversity of sugarcane parents in 9 series released by different breeding institutions, estimated based on polymorphisms of 5 SSR loci.

| Series | Clones size | NPB | PPB (%) | Na | Ne | h | I |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT | 13 | 47 | 53.41 | 1.534 | 1.262 | 0.162 | 0.250 |

| YT | 13 | 50 | 56.82 | 1.568 | 1.267 | 0.166 | 0.258 |

| YC | 10 | 49 | 55.68 | 1.557 | 1.283 | 0.178 | 0.275 |

| FN | 7 | 37 | 42.05 | 1.421 | 1.236 | 0.144 | 0.219 |

| MT | 8 | 44 | 50.00 | 1.500 | 1.259 | 0.161 | 0.247 |

| HoCP | 4 | 32 | 36.36 | 1.364 | 1.268 | 0.152 | 0.221 |

| CP | 10 | 36 | 40.91 | 1.409 | 1.222 | 0.136 | 0.181 |

| ROC | 13 | 46 | 52.27 | 1.523 | 1.259 | 0.160 | 0.247 |

| OTHER | 37 | 62 | 70.45 | 1.705 | 1.290 | 0.177 | 0.278 |

Genetic diversity parameters for the 5 microsatellite markers in the 9 sugarcane series were presented in Table 5, indicating that except the highest NPB value (62 stands for 70.45%) observed in OTHER series, the polymorphisms among eight determinate series were as follows: YT (50, 56.82%) > YC (49, 55.68%) > GT (47, 53.41%) > “ROC” (46, 52.27%) > MT (44, 50.00%) > FN (37, 42.05%) > CP (36, 40.91%) > HoCP (32, 36.36%). Observed numbers of alleles (Na) were higher in OTHER (Na = 1.705) and YT (Na = 1.568) series compared to those of the remaining seven series. Moreover, effective numbers of alleles (Ne) were also higher in OTHER (Ne = 1.290) and YC (Ne = 1.290) series compared to those of the remaining seven determinate series. Except OTHER series (h = 0.177, I = 0.278), both the gene diversity (h) and the Shannon information index (I) were higher in YC (h = 0.178, I = 0.275) series but lower in CP series (h = 0.136, I = 0.181).

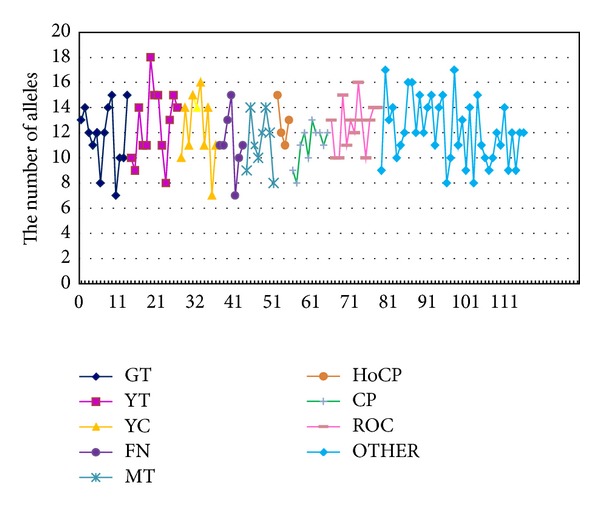

The number of alleles based on 5 SSR loci in different series of GT, YT, YC, FN, MT, HoCP, CP, “ROC,” and OTHER was illustrated in Figure 1. A total of 1,395 alleles were detected for all the 115 testing sugarcane accessions with an average of 12. The maximum number of alleles was 18 observed in YT93-159, while the minimum number was 7 in three accessions of GT90-55, YC96-48, and FN93-3608. Within the GT and FN series, the number of alleles both ranged from 7 to 15 with mean values of 11.8 and 11.1, respectively. In YT series, the number of alleles per locus ranged from 8 to 18 with an average of 12.6. Within MT series, the number of alleles ranged from 8 to 14, and the average number was 11.3. In HoCP series, the number of alleles was located between 11 and 15 with an average of 12.8. Within CP series, the number of alleles ranged from 8 to 13 with an average of 11.0. In “ROC” series, the number of alleles ranged from 10 to 16 with an average of 12.5. Within OTHER series, with an average of 12.0, the number of alleles was from 8 to 17.

Figure 1.

The number of alleles detected in 115 sugarcane accessions based on 5 SSR loci.

3.4. Cluster Analysis

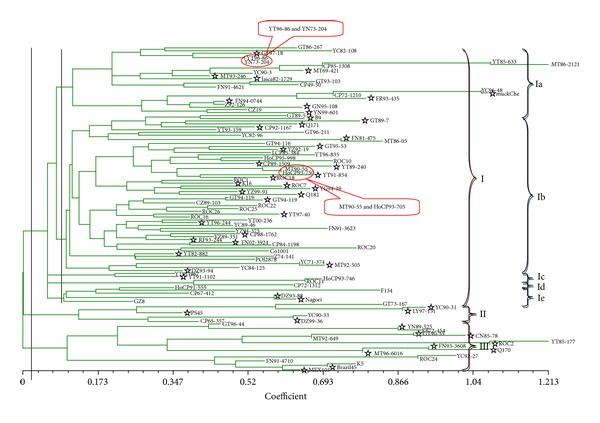

The measure of genetic distance (GD) can be applied to any kind of organism without regard to ploidy or mating scheme [36], with genetic distance estimates hardly affected by the sample size [37]. Therefore, in this study, a UPGMA dendrogram was constructed based on Nei's genetic distance (Figure 2), showing the genetic relationships among the various series, including single series of GT, YT, YC, FN, MT, HoCP, CP, and “ROC” and complex series of OTHER and that between two groups of common parents (64) and new parents (51). The 115 sugarcane parents were classified into three groups (Group I, Group II, and Group III) at the level of GD = 0.03. Group I consisted of 53 common parents and 38 new parents, including 10 from GT, 12 from YT, 7 from YC, 5 from FN, 6 from MT, 4 from HoCP, 9 from CP, 11 from “ROC,” and 27 from OTHER. Group II contained 3 common parents and 4 new parents, including 1 from GT, 2 from YC, 1 from CP, and 3 from OTHER. Group III contained 8 common parents and 9 new parents, including 2 from GT, 1 from YT, 1 from YC, 2 from FN, 2 from MT, 2 from “ROC,” and 7 from OTHER. At the level of GD = 0.09, Group I could be further divided into five subgroups (Subgroup Ia, Ib, Ic, Id, and Ie). Ia contained 15 common parents and 8 new parents, including 3 from GT, 2 from YT, 3 from YC, 2 from FN, 3 from MT, 3 from CP, and 7 from OTHER. Ib consisted of 30 common parents and 27 new parents, including 5 from GT, 10 from YT, 4 from YC, 3 from FN, 3 from MT, 2 from HoCP, 4 from CP, 10 from “ROC,” and 16 from OTHER. Ic had only two parents from YT containing 1 common parent and 1 new parent. Id contained 3 parents from each of HoCP, CP, and “ROC” and belonged to common parents. Ie contained 4 common parents and 2 new parents, including 1 from HoCP, 1 from CP and 4 from OTHER series.

Figure 2.

The UPGMA dendrogram of 115 Sugarcane parents based on 5 pairs of SSR primers.

It should be noted that Group I included most of the parents which came from different series. The above results demonstrate that the genotypes released by the same breeding institutions showed closer genetic relationships, except YC series released by Hainan sugarcane breeding station, which aimed at sugarcane germplasm innovation. It suggested that these parents should be useful in sugarcane cross breeding due to various genetic distances among them. Besides, a total of four testing accessions, including pairs of YT96-86 and YN73-204, plus MT90-55 and HoCP93-750, could not be distinguish based on the 5 microsatellite markers, and it may be due to their sharing of similar basis of genetic background.

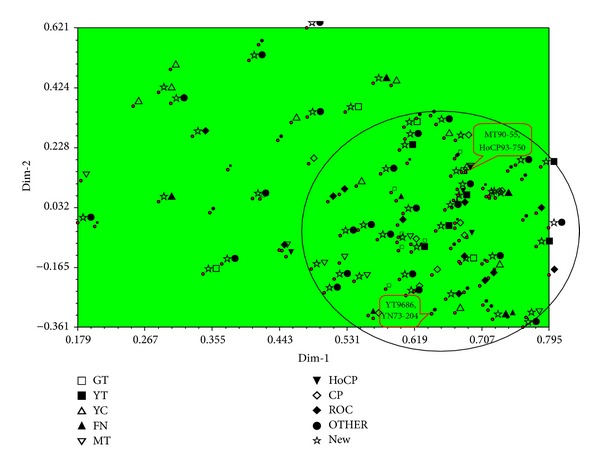

3.5. Principal Component Analysis

PCA examined a dissimilarity matrix of pairwise differences between specimens and used eigenvalue analysis in order to take the variation between specimens and condense them into a limited number of dimensions. The maximum amount of variation was plotted as the first axis, with subsequent variation of lesser magnitude explained by each additional dimension [38]. The principal component analysis, which can be helpful for illustrating the genetic relationships of sugarcane parents as individual units, was calculated based on the SSR data matrix of the 5 loci for all 115 sugarcane accessions occupied in this study (Figure 3). The first and second principal components accounted for a cumulative 76% of the variance, including 43% for common parents and 33% for new parents, respectively. As shown in Figure 3, 115 sugarcane parents were scattered in a limited space, covering 90% of CP series, 85% of YT and “ROC” series, 77% of GT series, 75% of MT and HoCP series, 73% of OTHER series, 71% of FN series, and 50% of YC series, respectively. We found that the distribution of sugarcane accessions in CP, YT, and “ROC” series was relatively narrow, while it was wider in YC, FN, and OTHER series. This revealed that genetic basis of the latter group was more extensive than the former group. Furthermore, the plots of two pairs of sugarcane accessions (YT96-86/YN73-204 and MT90-55/HoCP93-750) overlapped strongly (Figure 3). This analysis could not differentiate YT96-86 from YN73-204 or MT90-55 from HoCP93-750 at least at a molecular level based on the 5 SSR markers used in this study.

Figure 3.

Principal coordinates analysis (PCA) of 115 sugarcane parents using 5 pairs of SSR markers based on genetic similarity.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Improvement of sugarcane by genetic manipulation has been ongoing since 1888, following the observation in 1858 that sugarcane produced viable seed [1, 39]. According to the studies of Chen et al. (2011) and of Baver (1963), the contribution based on genetic improvement to increase the yield of cane sugar was estimated to be 75% of the yield increase attained by the Hawaiian sugar industry in the 1950s and more than 60% in the Chinese sugar industry in the last three decades [1, 40]. In Hawaii, the yield has improved every decade except in the 1970s, when disease problems plagued the sugar industry [40]. Although the degree to which varietal improvement has contributed to increase yield potential has varied widely from nation to nation, undoubtedly all nations have benefited to some degree by converting to newer, improved varieties from cross breeding. In addition, sugarcane is a potential bioenergy crop due to its high yield and high biomass. The world record and average in Hawaii (1978–1982) are 24.2 and 11.9 metric tons/ha/year, respectively. The 11.9 metric tons/ha/year represents a sugarcane dry matter yield of only 0.07 mt/ha/day, which is much lower than the theoretical maximum of 0.7 mt/ha/day estimated by Loomis and Williams [41].

In China, approximately 400 sugarcane varieties have been released in the last 50 years by cross breeding [42]. However, most of the sugarcane cultivars in the world can be dated back to only a few common ancestors [1, 19]. This may be due to the problem that the genetic basis of the sugarcane is limited; thus, new cultivars with interesting traits are difficult to be developed [43]. A similar situation has occurred in China, where the major cultivars in the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s were ROC10, ROC16, and ROC22, respectively. Thus, till now, the heterogeneity of cultivars has been very low since the variety ROC22 takes about 50%–60% of the total sugarcane planting area. This limits any further increase of sugar yield per unit and has many potential risks of suffering from common diseases [1]. Sugarcane cross breeding largely depends on broadening the genetic basis and the selection of parents for crossing. The Hainan Sugarcane breeding station is responsible for sugarcane hybridization in China, innovation targets of parents, and introduction of new parents into sugarcane hybridization programs. An increase in the genetic diversity of parental accessions should be helpful to broaden the genetic basis of the sugarcane [26, 44].

In the present study, the genetic diversity of 115 sugarcane parents was evaluated based on 5 microsatellite loci. These SSR markers were highly robust and codominant as characterized by high PIC value (0.84 on average), but exhibited the lower level of polymorphism described by Liu (2011) who reported average PIC value = 0.70 [24]. However, the level of polymorphism obtained in our and Pan's studies was much higher than other SSR markers reported by Filho et al. (2010), who reported mean PIC value = 0.57 [45]. Genetic diversity of different series including eight determinate and one complex (OTHER) series showed that YC series had higher genetic diversity (h = 0.188 and I = 0.275) except OTHER (h = 0.177 and I = 0.278) and that CP and FN series had lower ones (h = 0.136 and 0.144, I = 0.181 and 0.219, resp.). This is consistent with the results reported by Li et al. (2005) and Lao et al. (2008) [46, 47].

In the present study, all 64 accessions in common parents group showed relatively lower diversity, compared with the higher diversity exhibited by 51 accessions of new parents group. The result was based on the value of Nei's genetic diversity (h = 0.190 < 0.223) and Shannon's information index (I = 0.308 < 0.356), indicating that the innovation of parents has showed a positive role in sugarcane breeding programs in China, since the group of new parents has higher genetic diversity, and thus, it will to some degree benefit the broadening of the genetic basis in sugarcane hybridization.

The values of Nei's genetic diversity and Shannon's information index were much lower in other series than those in two groups. However, the level of diversity obtained in our research (two groups) was similar to previous research, which reported Nei's genetic diversity h = 0.222 and Shannon's information index I = 0.328 [13]. Since gene flow can resist the effect of genetic drift within populations and prevent the differentiation of populations with Nm > l, the genetic drift would lead to genetic differentiation among populations as the value of Nm < l [48]. The Nm value in this study was 4.762, indicating that there was no significant genetic differentiation between the two groups or nine series. The low genetic differentiation (Gst) among populations was primarily caused by the high level of gene flow. However, compared to wild sugarcane (Gst = 0.209) [13] and weedy rice (Gst = 0.387) [38], the Gst (0.095) of 115 sugarcane parents was still at a low level.

It is interesting that, in this study, both cluster and PCA analyses of individuals (including all the nine series) exhibited similar results: OTHER, YC, and GT series fell into three different groups and HoCP only belonged to Group I. Furthermore, a limited space covered 90% CP series, 85% YT and “ROC” series, and only 50% YC series, respectively. It was obvious that the distribution of accessions in CP, YT, and “ROC” series was relatively narrow while it was broader in YC, FN, and OTHER series. The results revealed that the genetic basis of YC, FN, and OTHER was more extensive than CP, YT, and “ROC” series, which also suggested that more attention should be made on the application of new parents in sugarcane hybrid breeding in the future. It was not difficult to find in the dendrogram (Figure 2) and PCA (Figure 3) that the clusters or components were closely related to their breeding institutions.

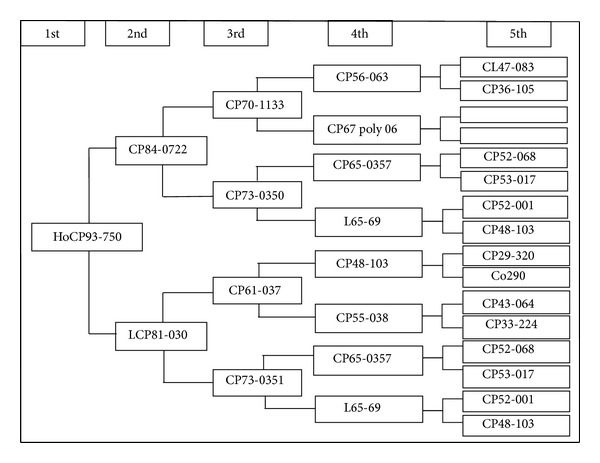

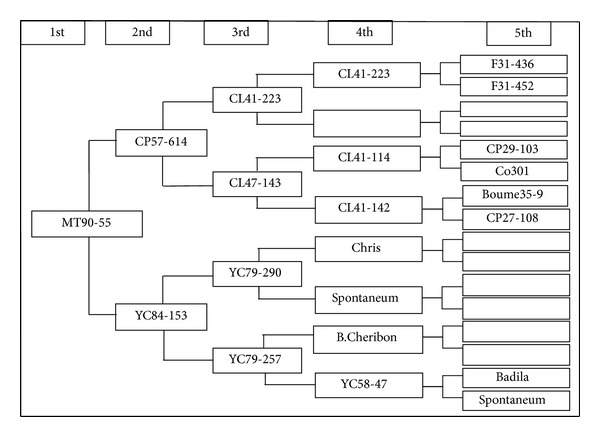

It was also apparent that there were two pairs of four accessions (YT96-86 and YN73-204 at the level of GD = 0.50 and MT90-55 and HoCP93-750 at the level of 0.59) which the analysis failed to differentiate. Furthermore, the PCA analysis indicated that the plots of YT96-86 and YN73-204 or MT90-55 and HoCP93-750 overlapped entirely. This shows that the analysis could not differentiate between these accessions at the molecular level based on the five testing SSR loci and indicated that more SSR loci would be necessary for differentiation from MT90-55 to HoCP93-750 and from YT96-86 to YN73-204. For example, based on the pedigree, HoCP93-750 evolved from CP84-0722 and LCP81-030, while MT90-55 derived from CP57-614 and YC84-153 (Figures 4 and 5). From the pedigree of HoCP93-750 and MT90-55, it is obvious that we could not find the same parents between the two sugarcane clones within five generations. Therefore, it is inaccurate to analyze the genetic structures, genetic diversity, or genetic relationships only by pedigree records. If we want to further identify the four sugarcane clones, more SSR loci should be applied.

Figure 4.

The pedigree of HoCP93-750.

Figure 5.

The pedigree of MT90-55.

According to previous reports, gSSR markers produce polymorphisms based on the difference in the number of DNA repeat units in regions of the genome and derive from genomic DNA libraries at a high price, while EST-SSRs detect variations in the expressed portion of the genome and can be mined from the EST databases at low price [20, 49, 50]. EST-SSR technology has been widely used in many plants, such as rice [51], sorghum [52], wheat [53], and several other plant species. However, the usefulness of EST-SSRs varies in different varieties of sugarcane, as the level of polymorphism (PIC = 0.23) was lower than that of anonymous SSR markers (PIC = 0.72) in sugarcane cultivars. It was also reported that EST-SSRs had higher level of polymorphism across ancestral species (PIC = 0.66 > 0.62) [20]. In other research, the number of alleles of gSSRs loci (7–9) was more than EST-SSRs loci (4–6), and about 35% of the gSSRs had PIC values around 0.90 in contrast to 15% of the EST-SSRs (50). What should also be stressed is that the two types of SSR, gSSR and EST-SSR, made no significant difference at the average genetic similarity (GS) based on Dice coefficient and were in good agreement with pedigree information for genetic relationships analysis [50]. These results demonstrated that, in the future, EST-SSRs should be used together with gSSRs for genetic relationship analysis in sugarcane.

From the above discussion, identifying useful gSSRs is significant, but in sugarcane, this can be a lengthy and difficult process due to their complexity and their abundance within the sugarcane genome [20, 50, 54]. Therefore, there is further work required to promote this technique. This paper used only 5 pairs of gSSR primers in the genetic diversity analysis of 115 sugarcane parents in spite of the testing SSR loci being selected from a batch of gSSR loci (221 ICSB sugarcane SSR markers) and having shown to be robust and polymorphic. This suggests that more basic Saccharum species, more gSSR markers, and more molecular methods like EST-SSRs can be utilized in further study.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) Project (2013AA102604) and the earmarked fund for the Modern Agriculture Technology of China (CARS-20). The authors especially thank Andrew C Allan in The New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research Ltd. (Plant and Food Research), Mt Albert Research Centre, Auckland, New Zealand, for his critical revision and valuable comments on this paper.

References

- 1.Chen RK, Xu LP, Lin YQ, et al. Modern Sugarcane Genetic Breeding. Beijing, China: China Agriculture Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo J, Deng ZH, Que YX, Yuan ZN, Chen RK. Productivity and stability of sugarcane varieties in the 7th round national regional trial of China. Chinese Journal of Applied and Environmental Biology. 2012;18(5):734–739. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson PA. Breeding for improved sugar content in sugarcane. Field Crops Research. 2005;92(2-3):277–290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skinner JC. Description of sugarcane clones. III. Botanical description. Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technology. 1972;14:124–127. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu YH, D’Hont A, Walker DIT, Rao PS, Feldmann P, Glaszmann JC. Relationships among ancestral species of sugarcane revealed with RFLP using single copy maize nuclear probes. Euphytica. 1994;78(1-2):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besse P, McIntyre CL, Berding N. Characterisation of Erianthus sect. Ripidium and Saccharum germplasm (Andropogoneae-Saccharinae) using RFLP markers. Euphytica. 1997;93(3):283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huckett BI, Botha FC. Stability and potential use of RAPD markers in a sugarcane genealogy. Euphytica. 1995;86(2):117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nair NV, Selvi A, Sreenivasan TV, Pushpalatha KN. Molecular diversity in Indian sugarcane cultivars as revealed by randomly amplified DNA polymorphisms. Euphytica. 2002;127(2):219–225. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aitken KS, Jackson PA, McIntyre CL. A combination of AFLP and SSR markers provides extensive map coverage and identification of homo(eo)logous linkage groups in a sugarcane cultivar. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2005;110(5):789–801. doi: 10.1007/s00122-004-1813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Godwin ID, Aitken EAB, Smith LW. Application of inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers to plant genetics. Electrophoresis. 1997;18(9):1524–1528. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Virupakshi S, Naik GR. ISSR Analysis of chloroplast and mitochondrial genome can indicate the diversity in sugarcane genotypes for red rot resistance. Sugar Tech. 2008;10(1):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li G, Quiros CF. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on a simple PCR reaction: its application to mapping and gene tagging in Brassica. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2001;103(2-3):455–461. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang D, Yang FY, Yan JJ, et al. SRAP analysis of genetic diversity of nine native populations of wild sugarcane, Saccharum spontaneum, from Sichuan, China. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2002;11(2):1245–1253. doi: 10.4238/2012.May.9.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alwala S, Suman A, Arro JA, Veremis JC, Kimbeng CA. Target region amplification polymorphism (TRAP) for assessing genetic diversity in sugarcane germplasm collections. Crop Science. 2006;46(1):448–455. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Que YX, Chen TS, Xu LP, Chen RK. Genetic diversity among key sugarcane clones revealed by TRAP markers. Journal of Agricultural Biotechnology. 2009;17(3):496–503. [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Hont A, Paulet F, Glaszmann JC. Oligoclonal interspecific origin of “North Indian” and “Chinese” sugarcanes. Chromosome Research. 2002;10(3):253–262. doi: 10.1023/a:1015204424287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Hont A. Unraveling the genome structure of polyploids using FISH and GISH; examples of sugarcane and banana. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2005;109(1–3):27–33. doi: 10.1159/000082378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkin MJ, Reader SM, Purdie KA, Miller TE. Detection of rDNA sites in sugarcane by FISH. Chromosome Research. 1995;3(7):444–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00713896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Hont A, Grivet L, Feldmann P, Rao S, Berding N, Glaszmann JC. Characterisation of the double genome structure of modern sugarcane cultivars (Saccharum spp.) by molecular cytogenetics. Molecular and General Genetics. 1996;250(4):405–413. doi: 10.1007/BF02174028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordeiro GM, Casu R, McIntyre CL, Manners JM, Henry RJ. Microsatellite markers from sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) ESTs cross transferable to Erianthus and sorghum. Plant Science. 2001;160(6):1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9452(01)00365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JSC, Chin ECL, Shu H, et al. An evaluation of the utility of SSR loci as molecular markers in maize (Zea mays L.): comparisons with data from RFLPS and pedigree. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1997;95(1-2):163–173. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang ZR, Pan FY, Wu WL, Peng DY, Yang JX. SSR markers application in sugarcane gentic breeding. Sugarcane and Canesugar. 2006;(6):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordeiro GM, Pan Y-B, Henry RJ. Sugarcane microsatellites for the assessment of genetic diversity in sugarcane germplasm. Plant Science. 2003;165(1):181–189. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu P, Que Y, Pan Y-B. Highly polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers for sugarcane germplasm evaluation and variety identity testing. Sugar Tech. 2011;13(2):129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan YB. Databasing molecular identities of sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) clones constructed with microsatellite (SSR) DNA markers. American Journal of Plant Sciences. 2010;1(2):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qi YW, Pan YB, Lao FY, et al. Genetic structure and diversity of parental cultivars involved in China mainland sugarcane breeding programs as inferred from DNA microsatellites. Journal of Integrative Agriculture. 2012;11(11):1794–1803. [Google Scholar]

- 27.dos Santos JM, Filho LSCD, Soriano ML, et al. Genetic diversity of the main progenitors of sugarcane from the RIDESA germplasm bank using SSR markers. Industrial Crops and Products. 2012;40(1):145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu CW. Analysis of the utilization and efficiency of the parents for sugarcane sexual hybridization in Yunnan. Sugarcane and Canesugar. 2002;4:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng HH, Li QW. Utilization of CP72-1210 in sugacane breeding program in mainland China. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences. 2007;11(1):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng HH, Li QW, Chen ZY. Breeding and utilization of new sugarcane parents. Sugarcane. 2004;11(3):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu CW, Liu JY, Zhao J, Zhao PF, Hou CX. Research on breeding potential and variety improvement of exotic parents in sugarcane. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences. 2008;21(6):1671–1675. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan Y-B, Scheffler BE, Richard EP., Jr. High-throughput molecular genotyping of commercial sugarcane clones with microsatellite (SSR) markers. Sugar Tech. 2007;9(2-3):176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeh FC, Boyle TJ. Popgene version 1. 31. Microsoft window-based freeware for population analysis. University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada, 1999.

- 34.Nei M. Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics. 1978;89(3):583–590. doi: 10.1093/genetics/89.3.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rohlf FJ. NTSYS-pc numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system, version 2.1. user guide. Exeter Software, Setauket, NY, USA, 2000.

- 36.Nei M. Genetic distance between populations. The American Naturalist. 1972;106(949):283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorman GC, Renzi J., Jr. Genetic distance and heterozygosity estimates in electrophoretic studies: effects of sample size. Copeia. 1979;2:242–249. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Dai W, Wu C, Song X, Qiang S. Genetic diversity and origin of Japonica- and Indica-like rice biotypes of weedy rice in the Guangdong and Liaoning provinces of China. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 2012;59(3):399–410. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevenson GC. Genetic and Breeding of Sugarcane. London, UK: Longmans; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baver LD. Practical lessons from trends in Hawaiian sugar production. Proceedings of the International Society of Sugar Cane Technology. 1963;11:68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loomis RS, Williams WA. Maximum crop productivity: an estimate. Crop Science. 1963;3:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Q, Qi YW, Zhang CM, Chen YS, Deng HH. Pedigree analysis of genetic relationship among core parents of sugarcane in mainland China. Guangdong Agricultural Sciences. 2009;13(10):44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edmé SJ, Miller JD, Glaz B, Tai PYP, Comstock JC. Genetic contribution to yield gains in the Florida sugarcane industry across 33 years. Crop Science. 2005;45(1):92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lima MLA, Garcia AAF, Oliveira KM, et al. Analysis of genetic similarity detected by AFLP and coefficient of parentage among genotypes of sugar cane (Saccharum spp.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2002;104(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/s001220200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Filho LSCD, Silva PP, Santos JM, et al. Genetic similarity among genotypes of sugarcane estimated by SSR and coefficient of parentage. Sugar Tech. 2010;12(2):145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li HM, Yang KZ, Wu SJ, Hong C. Discussion on the breeding effect of the CP parents series. Sugarcane and Canesugar. 2005;3:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lao FY, Liu R, He HY, et al. AFLP analysis of genetic diversity in series sugarcane parents developed at HSBS. Molecular Plant Breeding. 2008;6:517–522. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wright S. The genetical structure of populations. Annals of Eugenics. 1949;15(1):323–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1949.tb02451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gupta PK, Rustgi S, Sharma S, Singh R, Kumar N, Balyan HS. Transferable EST-SSR markers for the study of polymorphism and genetic diversity in bread wheat. Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 2003;270(4):315–323. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0921-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinto LR, Oliveira KM, Marconi T, Garcia AAF, Ulian EC, De Souza AP. Characterization of novel sugarcane expressed sequence tag microsatellites and their comparison with genomic SSRs. Plant Breeding. 2006;125(4):378–384. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moorthy KK, Babu P, Sreedhar M, et al. Identification of informative EST-SSR markers capable of distinguishing popular Indian rice varieties and their utilization in seed genetic purity assessments. Seed Science and Technology. 2011;39(2):282–292. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramu P, Kassahun B, Senthilvel S, et al. Exploiting rice-sorghum synteny for targeted development of EST-SSRs to enrich the sorghum genetic linkage map. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2009;119(7):1193–1204. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ercan S, Ertugrul F, Aydin Y, et al. An EST-SSR marker linked with yellow rust resistance in wheat. Biologia Plantarum. 2010;54(4):691–696. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tabasum S, Khan FA, Nawaz S, Iqbal MZ, Saeed A. DNA profiling of sugarcane genotypes using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA. Genetics and Molecular Research. 2010;9(1):471–483. doi: 10.4238/vol9-1gmr709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]