Abstract

A series of N,N-disubstituted piperazines were prepared and evaluated for binding to α4β2* and α7* neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors using rat striatum and whole brain membrane preparations, respectively. This series of compounds exhibited selectivity for α4β2* nAChRs and did not interact with the α7* nAChRs subtype. The most potent analogues were compounds 8b and 8f (Ki = 32 µM). Thus, linking together a pyridine π-system and a cyclic amine moiety via a piperazine ring affords compounds with low affinity, but good selectivity for α4β2* nicotinic receptors.

Structural analogues of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) agonists such as nicotine (NIC) and epibatidine have been suggested as potential therapeutic agents for several neurological disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.1–3

nAChRs are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels, composed of two types of subunits, α and β.4,5 To date, ten α (α1–α10) and four β (β1–β4) subunits have been identified.6 nAChRs have the general stoichiometry of 2α and 3β subunits that constitute the receptor/ion channel complex.7 Expression of nAChRs in Xenopus oocytes has shown that associations of α2, α3 and α4 subunits with β2 and β4 subunits forming functional heterologous receptor channels, whereas α7, α8, and α9 subunits assemble to form homologous subunit receptor channels.8–10 Differences in subunit composition contribute to nAChR pharmacology and functional diversity.11,12 Research is currently underway to identify the specific subunit composition of native nAChRs,6 the putative nature of which is indicated herein by an asterisk beside the subunit designation. The most prevalent nAChR subtypes in brain are the α4β2* and α7* subtypes. The α4β2* subtype binds [3H]NIC with high affinity, and the α7* subtype binds α-bungarotoxin (α-BTX) and methyllycaconitine (MLA) with high affinity. These receptor subtypes have been implicated as important in mediating the effect of nicotine improvement of cognition, learning and memory, as well as nicotine-induced analgesia, anxiolytic effects, and antidepressant effects, in addition to protection from neurodegeneration.13

Numerous studies have focused on the development of ligands for nAChRs,1,3,14,15 and several high affinity ligands have been reported.16–26 However, limited knowledge of the localization, structure and function of nAChRs, and the lack of selectivity of available ligands for the various nAChRs subtypes have prevented the extensive use of nAChR agonist and antagonists as therapeutic agents. Current drug discovery efforts in this area are being directed towards the development of subtype-selective neuronal nAChR ligands as therapeutic agents.27

A number of established nAChR ligands, such as epibatidine (1),28 (S)-NIC (2),27 (S)-nornicotine (3)13 and ABT-594 (4)29 possess potent binding affinity for central nAChRs. Epibatidine (1) is a natural alkaloid with high affinity for the α4β2* nAChR subtype in rat brain.28 The nAChR ligands 1–4 all contain pyridine and cyclic amine pharmacophoric moieties, and a comprehensive review, which summarized the structure–activity relationships of ligands for nAChRs,30 has emphasized the importance in the ligand structure of a π-system, such as a heteroaromatic ring or carbonyl group as a hydrogen bond acceptor moiety, and a basic cyclic amine group.

In addition, a series of compound 5 with micromolar affinity for neuronal nAChRs was reported,30 and N-dimethyl-N-phenylpiperazinium iodide (6, DMPP), a widely studied ligand, binds with high affinity to α4β2 and α7 receptors.2 In our continuing efforts to develop subtype-selective nAChRs ligands, a novel series of piperazine derivatives 7 and 8 (Tables 1 and 2), in which the pyridine π-system and cylic amine moieties are linked together via a piperazine ring, was thus designed by strutural hybridization of 5 and 6 with the well-known ligands 1–4. Like compound 4, compounds 7 and 8 are conformationally more flexible compared with compounds 1–3. The substituted pyridine units at ortho, meta or para position in these designed compounds are covered, and the chiral centers of these compounds are of S-configuration or racemate. We have now prepared and evaluated a series of N,N-disubstituted piperazines of general structure 7 and 8 for binding to α4β2* and α7* nAChRs,

Table 1.

Structures of compounds 7a–7e

| Compd | n | Stereochem | Substituted position of pyridine |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7a | 1 | S | ortho |

| 7b | 1 | S | meta |

| 7c | 2 | R, S | ortho |

| 7d | 2 | R, S | meta |

| 7e | 2 | R, S | para |

Table 2.

Structures of compounds 8a–8h

| Compd | n | Stereochem | R | Substituted position of pyridine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a | 1 | S | H | meta |

| 8b | 1 | S | CH3 | meta |

| 8c | 1 | S | H | para |

| 8d | 1 | S | CH3 | para |

| 8e | 2 | R, S | H | meta |

| 8f | 2 | R, S | CH3 | meta |

| 8g | 2 | R, S | H | para |

| 8h | 2 | R, S | CH3 | para |

Compounds 7a–7e were prepared by the method summarized in Scheme 1. N-Pyridylpiperazines 10 were obtained by modification of reported methods.31 Coupling of the N-Boc-protected cyclic amino acids 9 and compounds of general structure 10 with dicyclohexyl carbodiimide (DCC) and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT)31 gave the corresponding Boc-protected intermediates 11, which were further treated with TFA in CH2Cl2 to afford compounds 7a–7e.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) DCC, HOBT, CH2Cl2, rt. (b) TFA, CH2Cl2, rt.

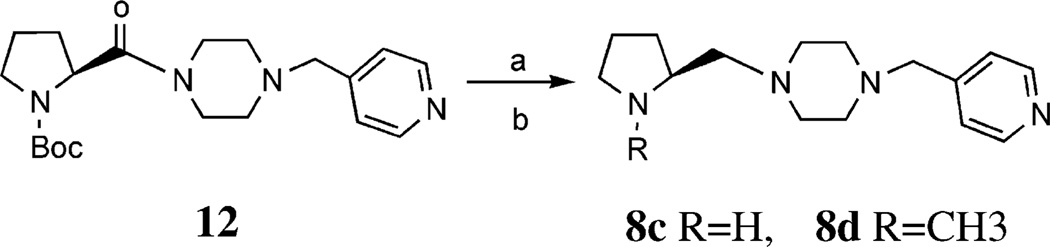

The generalmethod for the preparation of compounds 8a, 8b, and 8e–8h is summarized in Scheme 2. Reduction of 7b, 7d and 7e with BH3·THF in refluxing THF32 gave 8a, 8e and 8g, respectively, each of which was N-methylated with a 40% aqueous solution of formaldehyde and HCO2H to give 8b, 8f and 8h, respectively. The reduction of 7a and 7c by BH3·THF was unsuccessful. In a one-pot preparation of 8c and 8d, it was found that reduction of 12 with BH3·THF in refluxing THF followed by quenching with 6N HCl gave the expected 8c, and the methylated compound 8d simultaneously (Scheme 3).

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions: (a) BH3·THF, THF, reflux. (b) 40% HCHO aqueous solution, HCO2H, reflux.

Scheme 3.

Reagents and conditions: (a) BH3·THF, THF, reflux. (b) 6N HCl.

All novel compounds were characterized by IR, HRMS, 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy.33

Compounds listed in Table 3 were evaluated for their binding affinities for α4β2* and α7* nAChRs. MLA, α-BTX, NIC (2), and nornicotine (3) were also examined for comparison. Compounds were evaluated for their ability to inhibit [3H]NIC binding to rat striatal membranes and [3H]MLA binding to whole brain membranes, demonstrating affinity for α4β2* and α7* nAChRs, respectively.34,35 A brief description of the membrane preparation and ligand binding assays are provided below.36 Analogue-induced inhibition of binding was expressed as a percent of control and fitted by nonlinear, non-weighted least squares regression using a fixed slope sigmoidal function. The log IC50 value represented the logarithm of analogue concentration required to decrease binding by 50%. IC50 values were corrected for ligand concentration according to the Cheng-Prusoff equation37 to yield true inhibition constants (Ki), such that Ki = IC50/(1 + c/Kd), where c is the concentration of free radioligand and Kd is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the ligand. Protein concentration was determined using published methods.38 Results are reported as Ki values (±SEM). Both MLA and BTX had very high affinity for the α7* nAChR (Ki = 4.8 and 5.7 nM, respectively). MLA exhibited low affinity for the α4β2* nAChR (Ki = 1.46 µM). In contrast, NIC showed ~100-fold higher affinity for the α4β2* than for the α7* nAChR.

Table 3.

Ki values for 7a–7e and 8a–8h in [3H]NIC and [3H]MLA binding assaysa

| Compd |

Ki [3H]NIC binding assay (µM) |

Ki [3H]MLA binding assay (µM) |

|---|---|---|

| MLA | 1.46 ± 0.72 | 0.0048 ± 0.0004 |

| α-BTX | >10 | 0.0057 ± 0.0002 |

| 2 | 0.001 ± 0.00005 | 0.34 ± 0.01 |

| 3 | 0.033 ± 0.004 | 1.19 ± 0.11 |

| 7a | >100 | >100 |

| 7b | Ndb | Ndb |

| 7c | >100 | >100 |

| 7d | 54.8 ± 20.8 | >100 |

| 7e | 60.5 ± 25.7 | >100 |

| 8a | >100 | >100 |

| 8b | 31.7 ± 14.3 | >100 |

| 8c | 46 + 1.3 | >100 |

| 8d | 38.9 + 3.6 | >100 |

| 8e | >100 | >100 |

| 8f | 32.1 ± 1.5 | >100 |

| 8g | >100 | >100 |

| 8h | 42 ± 10.7 | >100 |

N = at least three independent determinations using triplicate nine-point inhibition curves.

Not determined.

Compared to NIC (2), compounds 7a–e and 8a–h generally exhibited lower affinity for the α4β2* nAChR; however generally these novel compounds were selective for the α4β2* nAChR, since none of the compounds exhibited affinity for α7* nAChR. It appears that the N-methyl compounds (8b, 8d, 8f and 8h) have a slightly higher affinity than those of their N-demethylated counterparts, exhibiting a similar trend to the relative binding affinities of NIC (2) and nornicotine (3). Also, the position of substitution of the piperazine moiety on the pyridine ring has no substantial influence on binding affinity. The most potent analogues were compounds 8b and 8f (Ki = 32 µM). Thus, linking together a pyridine π-system and a cyclic amine moiety via a piperazine ring affords compounds with low affinity but good selectivity for α4β2* nicotinic receptors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA 10934, DA00399, and DA 07304).

References and Notes

- 1.Holladay MW, Dart MJ, Lynch JK. J. Med. Chem. 1997;40:4169. doi: 10.1021/jm970377o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmitt JD. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000;7:749. doi: 10.2174/0929867003374660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd GK, Williams MJ. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;292:461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Le Novere N, Changeux JP. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;40:155. doi: 10.1007/BF00167110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ortells M, Lunt GG. Trends in Neurosci. 1995;18:121. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93887-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukas RJ, Changeux JP, Novere NL, Albuquerque EX, Balfour DJ, Berg DK, Bertrand D, Chiappinelli VA, Clarke PBS, Collins AC, Dani JA, Grady SR, Kellar KJ, Lindstrom JM, Marks MJ, Quik M, Taylor PW, Wonnacott S. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999;51:104397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper E, Courtier S, Ballivet M. Nature. 1991;350:235. doi: 10.1038/350235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papke RL, Boulter J, Patrick JH, Heinemann S. Neuron. 1989;3:589. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luetje CW, Patrick JJ. Neuroscience. 1991;11:837. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00837.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chavez-Noriega LE, Crona JH, Washburn MS, Urrutia A, Elliot KJ, Johnson EC. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;280:346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cachelin AB, Rust G. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 1995;429:449. doi: 10.1007/BF00374164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey SC, Luetje CW. J. Neuroscience. 1996;16:3798. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03798.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rui X, Dwoskin LP, Grinevich VP, Deaciuc G, Crooks PA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:1245. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glennon RA, Dukat M. Pharm. Acta Helv. 2000;74:103. doi: 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dwoskin LP, Xu R, Ayers JT, Crooks PA. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2000;10:1561. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bencherif M, Bane AJ, Miller CH, Dull GM, Gatto GJ. Eur J. Pharmacol. 2000;1:45. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00807-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng YX, Dukat M, Dowd M, Fiedler W, Martin B, Damaj MI, Glennon RA. Eur J. Med. Chem. 1999;34:177. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manetti D, Bartolini A, Borea PA, Bellucci C, Dei S, Ghelardini C, Gualtieri F, Romanelli MN, Scapecchi S, Teodori E, Varani K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999;7:457. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(98)00259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Davis CB, Rivero RA, Reitz AB, Shank RP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:1063. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin NH, Li Y, He Y, Holladay MW, Kuntzweiler T, Anderson DJ, Campbell JE, Arneric SP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:631. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin NH, Abreo MA, Gunn DE, Lebold SA, Lee EL, Wasicak JT, Hettinger AM, Daanen JF, Garvey DS, Campbell JE, Sullivan JP, Williams M, Arneric SP. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:2747. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00462-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferretti G, Dukat M, Giannella M, Piergentili A, Pigini M, Quaglia W, Damaj MI, Martin BR, Glennon RA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:2665. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi KI, Cha JH, Cho YS, Pae AN, Jin C, Yook J, Cheon HG, Daeyoung J, Kong JY, Koh HY. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1999;9:2795. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rádl S, Hezký P, Hafner W, Budìšínský M, Hejnová L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000;10:55. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00575-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balboni G, Marastoni M, Merighi S, Borea PA, Tomatis R. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000;35:979. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)01177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu R, Bai D, Chu G, Tao J, Zhu X. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1996;6:279. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lloyd GK, Menzaghi F, Bontempi B, Suto C, Siegel R, Akong M, Stauderman K, Velicelebi G, Johnson E, Harpold MM, Rao TS, Sacaan AI, Chavez-Noriega LE, Washburn MS, Vernier JM, Cosford NDP, McDonald LA. Life Sciences. 1998;62:1601. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bai D, Xu R, Zhu X. Drugs Future. 1997;22:1210. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holladay MW, Wasicak JT, Lin NH, He Y, Ryther KB, Bannon AW, Buckley MJ, Kim DJB, Decker MW, Anderson DJ, Campbell JE, Kuntzweiler TA, Donnelly-Roberts DL, Piattoni-Kaplan M, Briggs CA, Williams M, Arneric SPJ. Med. Chem. 1998;41:407. doi: 10.1021/jm9706224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tønder JE, Olesen PH. Curr. Med. Chem. 2001;8:651. doi: 10.2174/0929867013373165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carceller E, Merlos M, Giral M, Almansa C, Bartrolí J, García-Rafanell J, Forn J. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:2984. doi: 10.1021/jm00072a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown HC, Heim P. J. Org. Chem. 1973;38:912. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selected analytical data 7d: IR (film, cm−1) 3396, 2929, 1633, 1423, 1300, 1227, 1144, 1032, 1001, 716; HRMS (m/z): calcd for C16H24N4O: 288.1950, found 288.1958; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 8.54 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (dd, J = 1.7, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (m, 1H), 3.65–3.56 (m, 5H), 3.52 (s, 2H), 3.14 (m, 1H), 2.66 (m, 1H), 2.45–2.41 (m, 4H), 1.89 (br s, 1H), 1.71–1.31 (m, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 170.6, 149.5, 147.9, 135.9, 132.4, 122.6, 59.1, 55.3, 52.3, 51.8, 44.5, 44.4, 40.9, 28.9, 25.3, 23.3. 8 h: IR (film, cm−1) 2931, 2808, 1653, 1605, 1562, 1460, 1416, 1373, 1290, 1159, 1138, 1011, 841, 609; HRMS (m/z): calcd for C17H28N4O: 288.2314, found 288.2303; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 8.51 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 3.45 (s, 2H), 2.92 (d, J = 11.8 Hz, 1H), 2.68 (dd, J = 15.4, 7.7 Hz, 1H), 2.39 (m, 8H), 2.41(s, 3H), 2.26–2.18 (m, 3H), 1.83–1.61 (m, 3H), 1.41–1.25 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 149.6 (2 C), 147.6, 123.8 (2 C), 61.6, 61.3, 57.0, 53.7 (2 C), 53.1(2 C), 42.6, 30.0, 29.6, 24.6, 23.5.

- 34.Marks MJ, Stitzel JA, Romm E, Wehner JM, Collins AC. Mol. Pharmacol. 1986;30:427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies ARL, Hardick DJ, Blagbrough IS, Potter BVL, Wolstenholme AJ, Wonnacott S. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:679. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Membranes from rat striata and whole brain (excluding cerebellum, cortex and striatum) were prepared for the [3H]NIC and [3H]MLA binding assays, respectively. Striata or whole brain was homogenized with a Tekmar polytron in 10–20 vol of ice-cold modified Krebs-HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 118 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, pH 7.5). Homogenates were incubated (5 min at 37°C) and centrifuged (20 min at 29,000g at 4 °C). Tissue pellets were resuspended in 10 vol of ice-cold Milli-Q water, incubated (5–10 min at 37 °C) and centrifuged for 20 min (29,000g at 4 °C). Tissue pellets were again resuspended in 10 vol of ice-cold 10% Krebs-HEPES buffer, incubated and centrifuged as described and stored at −70 °C in 10% Krebs-HEPES buffer until use. Membrane suspension (150–200 mg protein/100 mL) was added to assay tubes containing analogue (7–9 concentrations, 1 nM–1 mM) and 3 nM [3H]NIC or 3 nM [3H]MLA for a final assay vol of 200–250 µL. Subsequently, [3H]NIC and [3H]MLA assays were incubated for 90 and 120 min, respectively. Reactions were terminated by addition of ice-cold buffer and rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters. Bound radioactivity was determined via liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 mM NIC ([3H]NIC binding assay) and 1 mM NIC ([3H]MLA binding assay).

- 37.Cheng Y, Prussoff WH. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradford MM. Ann. Biochem. 1976;72:248. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]