Abstract

Objective:

To examine the joint hierarchical structure of two measures of adolescent personality pathology within a community sample of Canadian adolescents.

Method:

Self-reported data on demographic information and pathological personality traits were obtained from 144 youth (Mage = 16.08 years, SD = 1.30). Personality pathology was measured using the youth-version of the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP-Y; Linde, Stringer, Simms, & Clark, in press) and the Dimensional Personality Symptom Item Pool (DIPSI; De Clercq, De Fruyt, Van Leeuwen, & Mervielde, 2006). Lower-order scales were subjected to structural hierarchical analyses.

Results:

Scales from the two measures were complementary in defining higher-order traits. Traits at the 4-factor level of the hierarchy (Need for Approval, Disagreeableness, Detachment, and Compulsivity) showed similarities and differences with previous results in adults.

Conclusions:

The current investigation integrated top-down and bottom-up measures for a comprehensive account of the higher-order hierarchy of adolescent personality pathology. Results are discussed in the context of convergence across approaches and in comparison with previous findings in adult samples.

Keywords: adolescents, personality pathology, personality hierarchy

Résumé

Objectif:

Examiner la structure hiérarchique conjointe de deux mesures de la pathologie de la personnalité adolescente dans un échantillon communautaire d’adolescents canadiens.

Méthode:

Des données autoévaluées sur l’information démographique et les traits de personnalité pathologique ont été obtenues de 144 adolescents (Mâge = 16,08 ans, ET = 1,30). La pathologie de la personnalité a été mesurée à l’aide de la version pour adolescents de la Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP-Y; Linde, Stringer, Simms, et Clark, 2012) et du Dimensional Personality Symptom Item Pool (DIPSI; De Clercq, De Fruyt, Van Leeuwen, et Mervielde, 2006). Des échelles d’ordre inférieur ont fait l’objet d’analyses structurelles hiérarchiques.

Résultats:

Les échelles des deux mesures étaient complémentaires pour définir les traits d’ordre supérieur. Les traits au niveau des quatre facteurs de la hiérarchie (détachement, désobligeance, besoin d’approbation, et compulsivité) montraient des ressemblances et des différences relativement aux résultats précédents chez les adultes.

Conclusions:

La présente recherche intégrait des mesures descendantes et ascendantes pour un compte rendu complet de la hiérarchie d’ordre supérieur de la pathologie de la personnalité adolescente. Les résultats sont présentés dans le contexte de la convergence entre les approches et en comparaison avec les résultats précédents d’échantillons adultes.

Keywords: adolescents, pathologie de la personnalité, hiérarchie de la personnalité

The categorical conceptualization of DSM-IV-TR personality disorders (PDs; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) is subject to substantial limitations, including excessive diagnostic co-morbidity, diagnostic heterogeneity, inadequate symptom representation, and arbitrary diagnostic thresholds (Trull & Durrett, 2005). Adoption of a dimensional maladaptive trait model has the potential to overcome these limitations (Widiger & Trull, 2007). Such a shift would also enhance consistency with models of normative personality, which have long utilized hierarchically organized dimensional models (Digman, 1997; Markon, 2009; Wright et al., 2012), thereby improving communication across areas of research. Popular dimensional measures of personality pathology have largely been developed for adult populations (Widiger & Simonsen, 2005), with fewer measures developed for youth (e.g., De Clercq et al., 2006; Linde et al., in press).

To better understand the nature and organization of adult higher-order PD traits, researchers have begun building consensus on the higher-order hierarchical structure (Kushner, Quilty, Tackett, & Bagby, 2011; Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005; Wright et al., 2012). Two recent investigations (Kushner et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2012) using similar analytic approaches found converging evidence for Level 4 hierarchy components, identified as Emotional Dysregulation/Negative Affect, Inhibitedness/Detachment, Dissocial Behavior/Antagonism, and Compulsivity. These hierarchical findings were consistent with the four broad dimensions that have emerged most consistently across models of adult personality pathology (Livesley, Jang, & Vernon, 1998; Widiger & Simonsen, 2005). Components emerging at Level 5, however, notably differed. Specifically, Wright et al. (2012) extracted a Psychoticism component (i.e., Harkness & McNulty, 1994; Tackett, Silberschmidt, Krueger, & Sponheim, 2008), which encompassed eccentricity, perceptual dysregulation, and unusual beliefs, whereas Kushner et al. (2011) extracted a Need for Approval component (i.e., Clark, Livesley, Schroeder, & Irish, 1996), covering dependency and interpersonal difficulties. These discrepancies, at least in part, reflected differences in item pools and content (e.g., differential coverage of peculiarity). To the best of our knowledge, none of this work to date has extended this research to youth.

The current lack of understanding regarding PD trait structure and organization in youth reflects a general lag in research on child and adolescent manifestations of personality pathology, relative to such work with adults (Tackett, Balsis, Oltmanns, & Krueger, 2009; Westen, Shedler, Durrett, Glass, & Martens, 2003). Indeed, most measures of youth personality pathology have been developed as downward extensions of measures originally designed for use in adult populations (e.g., Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire-DAPP-BQ; Livesley & Jackson, 2009; Tromp & Koot, 2008; Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality-SNAP; Clark, 1993; Linde et al., in press). Following this “top-down” approach, instruments designed for use with adults are adapted for younger populations (see De Fruyt & De Clercq, 2012; 2013). Items for such measures do not necessarily represent age-specific behaviours, but rather represent DSM-IV Axis II symptoms or PD items developed for adult samples (De Clercq, De Fruyt, & Widiger, 2009; Shiner, 2007; Widiger, De Clercq, & De Fruyt, 2009). Thus, it is unsurprising that the factor structures of such instruments resemble their adult counterparts (Clark, 1993; Linde et al., in press). It therefore remains an important empirical issue to tackle the extent to which such measures provide adequate coverage of youth PD traits, and the extent to which such coverage is overlapping and unique relative to adult measures.

In response to the limitations of top-down assessment instruments, De Clercq, De Fruyt, and Mervielde (2003) developed the Dimensional Personality Symptom Item Pool (DIPSI) using a bottom-up approach to identifying and defining youth-specific maladaptive traits. That is, De Clercq and colleagues constructed a maladaptive trait item pool, which was derived from parental descriptions of normative childhood personality. The DIPSI items corresponded to 27 lower-order facets and four higher-order dimensions, labeled Disagreeableness, Emotional Instability, Introversion, and Compulsivity. The structure of the DIPSI suggests conceptual convergence with adult personality pathology inventories (De Clercq et al., 2006), such as the SNAP and DAPP-BQ (Clark et al., 1996; Livesley et al., 1998), and preliminary evidence has indicated significant associations between the DIPSI and the DAPP-BQ at the four-factor level (De Clercq et al., 2009). The current investigation addresses the issue of convergence among youth PD instruments from a structural perspective, and more specifically aims to evaluate the joint structure of a top-down and a bottom-up measure of personality pathology within a community sample of adolescents.

Current investigation

The current investigation examines the hierarchical structure of two youth-specific measures of pathological traits: The DIPSI and the SNAP-Y. Parallel to previous studies with adults that have highlighted extraction up to Level 5 (Kushner et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2012), we extracted one through five factors from the 42 lower-order DIPSI and SNAP-Y facets. We hypothesized that components extracted at Level 2 would resemble broad factors of Internalizing and Externalizing, which have emerged in previous research on pathological traits (De Clercq et al., 2006; Wright et al., 2012) and general psychopathology (Achenbach, 1974; Krueger, 1999). At Level 4, we hypothesized that factors would resemble the basic dimensions of adult personality pathology: Emotional Instability, Disagreeableness, Detachment, and Compulsivity (Kushner et al., 2011; Livesley et al., 1998; Wright et al., 2012). Finally, given little coverage of content related to Psychoticism on either the SNAP-Y or DIPSI, we hypothesized that a fifth factor resembling Need for Approval would emerge, based on its representation in research on adults (Clark et al., 1996; Kushner et al., 2011). Exploratory goals of the study were to highlight the extent to which higher-order trait coverage overlapped between DIPSI and SNAP-Y measures, as well as the extent to which each of the two measures may capture content not well-represented by the other.

Method

Sample and procedure

Participants were 144 adolescents (65 male, 79 female) aged 12–18 years old (Mage = 16.08, SD = 1.29). All participants were solicited using a community-based participant pool database and flyers posted throughout an urban community in southern Ontario. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were fluency in English and an absence of neurodevelopmental disorders, psychotic disorders, and mental retardation in the child. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents. Within the current sample, the following ethnicity breakdown was reported by parents: 72.2% European, 7.0% Asian, 3.5% African/Caribbean, 1.4% Latin American, 11.1% other, and 4.9% unknown.

Data for this investigation were drawn from a larger longitudinal study examining the role of personality traits in predicting behavioral outcomes. In total, 185 youth aged 11–17 years at intake were invited for a follow-up assessment. The current sample is composed of youth who completed this second assessment 1–3 years following their initial participation. Ethics approval was obtained from the research ethics board. Packages including informed consent documentation and questionnaires were mailed to participants to be completed and returned at an in-lab visit, during which they completed an extended battery of psychological tests; however, a subsample (n = 38) of participants was unable to attend and therefore returned completed questionnaires by mail. Youth participants received a $15–25 gift card for completing the protocol. For the current analyses, missing data were imputed using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm in SPSS 20.

Measures

Dimensional Personality Symptom Item Pool (DIPSI; De Clercq et al., 2006; Tackett & De Clercq, 2009)

The DIPSI is a 172-item self-report questionnaire measuring personality pathology in youth. The DIPSI was originally developed with 5–15 year old Belgian youth (De Clercq et al., 2006), and was translated into English with validation data suggesting excellent psychometric properties (Tackett & De Clercq, 2009). Items from the DIPSI are scored to generate scales for four higher-order dimensions of mal-adaptive personality: Disagreeableness, Emotional Instability, Introversion, and Compulsivity; and 27 lower-order facets: Hyperexpressive Traits, Hyperactive Traits, Dominance–Egocentrism, Impulsivity, Irritable-Aggressive Traits, Disorderliness, Distraction, Risk-taking, Narcissistic Traits, Affective Lability, Resistance, Lack of Empathy, Dependency, Anxious Traits, Lack of Self-Confidence, Insecure Attachment, Submissiveness, Ineffective Coping, Separation Anxiety, Depressive Traits, Inflexibility, Shyness, Paranoid Traits, Withdrawn Traits, Perfectionism, Extreme Achievement Striving, and Extreme Order. Internal consistencies (coefficient alpha) for the English language DIPSI scales from the present sample are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Scale Reliabilities for the Dimensional Symptom Pool Items (DIPSI) and Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality-Youth Version (SNAP-Y) Facets

| Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIPSI facets | |||||

| Hyperexpressive traits | 2.18 | 0.74 | 0.48 (0.20) | 0.06 (0.40) | .83 |

| Hyperactive traits | 2.44 | 0.76 | 0.33 (0.20) | −0.29 (0.40) | .77 |

| Dominance–egocentrism | 2.26 | 0.76 | 0.18 (0.20) | −0.86 (0.40) | .82 |

| Impulsivity | 1.90 | 0.80 | 0.64 (0.20) | −0.43 (0.40) | .81 |

| Irritable-aggressive traits | 1.85 | 0.75 | 1.06 (0.20) | 0.60 (0.40) | .89 |

| Disorderliness | 2.38 | 0.79 | 0.44 (0.20) | −0.15 (0.40) | .84 |

| Distraction | 2.08 | 0.78 | 0.54 (0.20) | −0.61 (0.40) | .84 |

| Risk-taking | 2.38 | 0.86 | 0.34 (0.20) | −0.56 (0.40) | .85 |

| Narcissistic traits | 2.52 | 0.80 | 0.61 (0.20) | −0.02 (0.40) | .83 |

| Affective lability | 2.10 | 0.94 | 0.97 (0.20) | 0.45 (0.40) | .88 |

| Resistance | 1.63 | 0.66 | 1.27 (0.20) | 1.10 (0.40) | .81 |

| Lack of empathy | 1.53 | 0.53 | 1.11 (0.20) | 0.67 (0.40) | .84 |

| Dependency | 1.85 | 0.78 | 0.61 (0.20) | −0.68 (0.40) | .81 |

| Anxious traits | 2.16 | 0.86 | 0.50 (0.20) | −0.73 (0.40) | .86 |

| Lack of self-confidence | 2.06 | 0.94 | 0.76 (0.20) | −0.35 (0.40) | .83 |

| Insecure attachment | 2.10 | 0.71 | 0.35 (0.20) | −0.63 (0.40) | .56 |

| Submissiveness | 1.98 | 0.73 | 0.70 (0.20) | 0.12 (0.40) | .84 |

| Ineffective coping | 2.34 | 0.93 | 0.50 (0.20) | −0.77 (0.40) | .91 |

| Separation anxiety | 1.64 | 0.79 | 1.32 (0.20) | 1.23 (0.40) | .74 |

| Depressive traits | 2.12 | 0.94 | 0.65 (0.20) | −0.50 (0.40) | .80 |

| Inflexibility | 2.09 | 0.67 | 0.23 (0.20) | −0.65 (0.40) | .81 |

| Shyness | 1.65 | 0.67 | 1.34 (0.20) | 1.63 (0.40) | .86 |

| Paranoid traits | 1.76 | 0.86 | 1.29 (0.20) | 1.10 (0.40) | .89 |

| Withdrawn traits | 2.23 | 0.73 | 0.38 (0.20) | −0.81 (0.40) | .73 |

| Perfectionism | 2.45 | 0.93 | 0.55 (0.20) | −0.28 (0.40) | .81 |

| Extreme achievement striving | 2.91 | 0.89 | 0.19 (0.20) | −0.42 (0.40) | .70 |

| Extreme order | 2.32 | 0.82 | 0.78 (0.20) | 0.30 (0.40) | .83 |

| SNAP-Y facets | |||||

| Negative temperament | 11.58 | 6.46 | 0.38 (0.20) | −0.79 (0.40) | .90 |

| Positive temperament | 18.13 | 6.28 | −0.63 (0.20) | −0.46 (0.40) | .90 |

| Disinhibition (pure) | 5.68 | 3.14 | 0.26 (0.20) | −0.58 (0.40) | .77 |

| Mistrust | 5.75 | 4.01 | 0.78 (0.20) | 0.23 (0.40) | .83 |

| Manipulativeness | 6.34 | 4.01 | 0.44 (0.20) | −0.49 (0.40) | .81 |

| Aggression | 4.36 | 3.64 | 1.24 (0.20) | 1.59 (0.40) | .83 |

| Self-harm | 2.11 | 2.92 | 1.72 (0.20) | 2.71 (0.40) | .87 |

| Eccentric perceptions | 4.86 | 3.77 | 0.77 (0.20) | −0.42 (0.40) | .86 |

| Dependency | 5.80 | 3.30 | 0.57 (0.20) | 0.29 (0.40) | .74 |

| Exhibitionism | 7.29 | 4.20 | 0.26 (0.20) | −0.76 (0.40) | .86 |

| Entitlement | 7.10 | 3.82 | 0.34 (0.20) | −0.61 (0.40) | .82 |

| Detachment | 5.48 | 4.01 | 0.77 (0.20) | −0.01 (0.40) | .83 |

| Impulsivity | 5.92 | 3.72 | 0.65 (0.20) | −0.01 (0.40) | .82 |

| Propriety | 12.09 | 3.92 | −0.26 (0.20) | −0.42 (0.40) | .81 |

| Workaholism | 6.55 | 3.62 | 0.42 (0.20) | −0.28 (0.40) | .82 |

Note. Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 144.

Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality – Youth Version (SNAP-Y; Linde et al., in press)

The SNAP-Y is a 390-item self-report questionnaire measuring personality pathology in youth. The SNAP-Y is a “top-down” measure, in that it was adapted from a measure originally developed for use in adult populations (Clark, 1993); however, it is notable that the higher- and lower-order dimensions of the original adult version were developed using a bottom-up analytic strategy (i.e., derived from item-level data). The SNAP-Y has since been validated within a community sample of 364 youth (Linde et al., in press). Items from the SNAP-Y can be scored to generate scales for three higher-order dimensions: Negative Emotionality, Positive Emotionality, and Disinhibition versus Constraint; as well as 15 lower-order facets: Negative Temperament, Positive Temperament, Disinhibition (Pure), Mistrust, Manipulativeness, Aggression, Self-harm, Eccentric Perceptions, Dependency, Exhibitionism, Entitlement, Detachment, Impulsivity, Propriety, and Workaholism. Internal consistency (coefficient alpha) for the SNAP-Y scales from the present sample are listed in Table 1.

Results

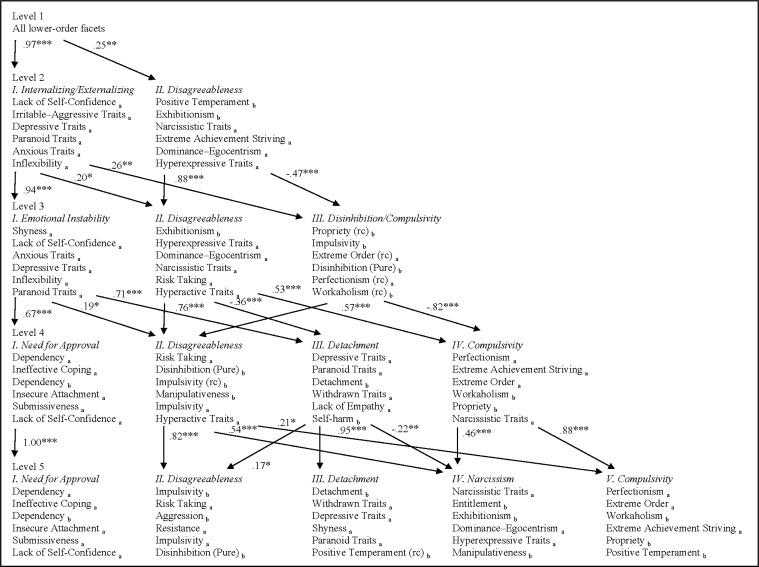

Goldberg’s (2006) method was used to explore the hierarchical structure of the DAPP-BQ. This method involves the top-down extraction of higher order traits from a set of variables to derive a hierarchical structure. Specifically, the 42 DIPSI and SNAP-Y facets were subjected to principal components analyses with varimax rotation, beginning with the first principal component and iteratively extracting successive levels of the hierarchy. Regression-based factor scores at each level were then correlated to provide “path estimates” between factors at contiguous levels of the hierarchy. Figure 1 displays the five levels of the hierarchy delineated using this method, including the top six facets defining each component. Complete factor loading matrices are available from the first author upon request. All analyses were conducted in SPSS.

Figure 1.

The joint structure of the Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality (SNAP-Ya) and the Dimensional Personality Symptom Item Pool (DIPSIb). Paths represent correlations among regression-based factor scores at contiguous levels of the hierarchy.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

Level 2 of the joint personality hierarchy indicated two broad components reflecting characteristics of Internalizing/Externalizing and Disagreeableness, respectively. The second component broke off to form separate components reflecting Disagreeableness and Disinhibition/Compulsivity at Level 3. At Level 4, Emotionality Instability breaks down into Need for Approval and Detachment. Finally, at Level 5, a component reflecting Narcissism split off from Disagreeableness and Disinhibition/Compulsivity. Variance accounted for at Levels 1–5 was 37.92%, 48.99%, 58.89%, 64.75%, and 68.84%, respectively.

Discussion

The current investigation represents the first examination of the hierarchical structure of adolescent PD traits via the joint analysis of a top-down and a bottom-up measure. Across all levels of the hierarchy, components were composed of both SNAP-Y and DIPSI scales, suggesting substantial overlap (at the higher-order level, at least) in the content covered by these top-down and bottom-up measures. Further, the resulting hierarchy components are analogous to higher-order dimensions observed in previous research on adults (Kushner et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2012), although notable discrepancies also emerged.

Surprisingly, we did not observe separate components reflecting Internalizing and Externalizing problems at Level 2 of the hierarchy, which have been observed previously in adults (Krueger, 1999; Wright et al., 2012) and youth (Achenbach, 1974; Lahey et al., 2004); however, this content was reflected in a joint negative affect component. The Level 2 components identified here appear to reflect mal-adaptive approach-avoidance (Internalizing/Externalizing) and self-regulation (Disagreeableness) characteristics of normative personality models (DeYoung, 2006; Digman, 1997; Tackett et al., 2012), demonstrating consistency with broad dimensions of normative personality. At Level 3, Disinhibition/Compulsivity split off from Disagreeableness. The Disagreeableness component encompassed attention-seeking, antagonism, and risk-taking, similar to the Disagreeable factor observed by De Clercq and colleagues (2006). There were notable differences, however, from related components in the adult hierarchy. Specifically, adult Dissocial/Antagonism components have generally captured more overt Externalizing behaviours (e.g., hostility and antisocial rule-breaking; Kushner et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2012). In the adolescent hierarchy, these aspects of aggression loaded more highly on Emotional Instability than Disagreeableness, suggesting a stronger link between aggressive and nonaggressive negative affect among youth than adults. Similar results were observed for the normative personality hierarchy derived by Tackett and colleagues (2012), wherein antagonism played a more prominent role in adolescent neuroticism components than is typically observed among adults.

At Level 4, a “typical” Negative Affect factor was not observed despite its presence in adult hierarchies of personality pathology (Kushner et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2012). Rather, Emotional Instability bifurcated into Detachment and Need for Approval. Detachment was primarily characterized by depression, distrust, and withdrawal, and resembled the Inhibitedness/Detachment component of adult hierarchies (Kushner et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2012). Scales measuring resistance and aggression also shared secondary loadings on Detachment and Disagreeableness, further demonstrating the link between aggressive and nonaggressive negative affect in youth, relative to adults (Tackett et al., 2012). Need for Approval was largely characterized by dependency and related interpersonal difficulties, thus showing overlap with previous studies of adult personality pathology (Clark et al., 1996; Kushner et al., 2011), although not typically at the fourth level of the hierarchy.

Finally, the Level 5 Narcissism component – which encompassed narcissism and entitlement – captured a narrow band of behaviour and explained limited additional variance of the pathological traits (4.09%), suggesting that it may best represent a lower-order facet. We therefore suggest that Level 4 components provided the optimal level of resolution for capturing adolescent personality pathology.

The current research provides the first empirical investigation of the shared structure of two independently derived measures of youth personality pathology. Overall, we observed content overlap among these top-down and bottom-up measures, although some discrepancies emerged. For example, the SNAP-Y Impulsivity facet loaded negatively on Disagreeableness with negative secondary loadings on Disinhibition/Compulsivity, whereas the DIPSI Impulsivity facet loaded positively on Disagreeableness. These results suggest that similarly labeled facets from top-down versus bottom-up measures may be tapping somewhat different constructs, underscoring the relevance of taking into account the specific background and construction procedure of trait measures when interpreting test results. The current investigation also helps bridge gaps among previously disparate areas, including research with adult samples and with normative child personality data. Importantly, overlap between higher-order pathological traits observed in adolescence and adulthood support the hypothesis that PD traits emerge prior to adulthood and show structural stability (De Bolle et al., 2009), whereas age-related discrepancies may point to areas of change during development. Research investigating the extent to which such differences reflect personality symptoms versus normative developmental changes is therefore needed.

Despite these contributions, the current results are subject to two limitations. First, the sample size is modest, with a need for future work utilizing larger sample to replicate and extend this study. Second, the results are limited to the current community sample and are thus less likely to reflect broader variance of maladaptive traits that may be observable among adolescents in clinical settings, which represents another important extension for future work. In sum, this research serves to advance our understanding of the nature and structure of adolescent PD traits, an understudied area of research in need of increased empirical attention.

Acknowledgements/Conflicts of Interest

The authors would like to express gratitude to Dr. Lee Anna Clark for her comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Support for this investigation was provided by a research award from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation to JLT and a graduate-level studentship awarded by the Ontario Mental Health Foundation to SCK. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

References

- Achenbach TM. Developmental psychopathology. Oxford, UK: Ronald Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA. Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Livesley WJ, Schroeder ML, Irish SL. Convergence of two systems for assessing specific traits of personality disorder. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8(3):294–303. [Google Scholar]

- De Bolle M, De Clercq B, Van Leeuwen K, Decuyper M, Rosseel Y, De Fruyt F. Personality and psychopathology in Flemish referred children: Five perspectives of continuity. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2009;40(2):269–285. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, Mervielde I. Construction of the Dimensional Personality Symptom Item Pool (DIPSI) Ghent, BE: Ghent University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, Van Leeuwen K, Mervielde I. The structure of maladaptive personality traits in childhood: A step toward an integrative developmental perspective for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115(4):639–657. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, Widiger TA. Integrating a developmental perspective in dimensional models of personality disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, De Clercq B. Childhood antecedents of personality disorders. In: Widiger TA, editor. The Oxford handbook of personality disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 166–185. [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, De Clercq B. Childhood antecedents of personality disorder: A Five-Factor Model perspective. In: Widiger TA, Costa PT Jr, editors. Personality disorders and the Five-Factor Model of personality. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG. Higher-order factors of the Big Five in a multi-informant sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(6):1138–1151. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73(6):1246–1256. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. Doing it all Bass-Ackwards: The development of hierarchical factor structures from the top down. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:347–358. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness AR, McNulty JL. The Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5): Issues from the pages of a diagnostic manual instead of a dictionary. In: Strack S, Lorr M, editors. Differentiating normal and abnormal personality. New York, NY: Springer; 1994. pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SC, Quilty LC, Tackett JL, Bagby RM. The hierarchical structure of the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology (DAPP-BQ) Journal of Personality Disorders. 2011;25(4):504–516. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2011.25.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Applegate B, Waldman ID, Loft JD, Hankin BL, Rick J. The structure of child and adolescent psychopathology: Generating new hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(3):358–385. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde JA, Stringer DM, Simms LJ, Clark LA. The Schedule for Nonadaptive and Adaptive Personality for Youth (SNAP-Y): A new measure for assessing adolescent personality and personality pathology. Assessment. doi: 10.1177/1073191113489847. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jackson DN. Manual for the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology—Basic Questionnaire. Port Huron, MI: Sigma Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:941–948. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE. Hierarchies in the structure of personality traits. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2009;3(5):812–826. [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88(1):139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL. Personality disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Assessment of childhood disorders. 4th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 781–816. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Balsis S, Oltmanns TF, Krueger RF. A unifying perspective on personality pathology across the life span: Developmental considerations for the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:687–713. doi: 10.1017/S095457940900039X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, De Clercq B. Assessing childhood precursors to personality pathology: Validating the English version of the DIPSI; 2009, September; Talk presented at the 10th annual meeting of the European Conference on Psychological Assessment; Ghent, BE. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Silberschmidt AL, Krueger RF, Sponheim SR. A dimensional model of personality disorder: Incorporating DSM Cluster A characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):454–459. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tackett JL, Slobodskaya HR, Mar RA, Deal J, Halverson CF, Jr, Baker SR, Besevegis E. The hierarchical structure of childhood personality in five countries: Continuity from early childhood to early adolescence. Journal of Personality. 2012;80(4):1–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromp NB, Koot HM. Dimensions of personality pathology in adolescents: Psychometric properties of the DAPPBQ-A. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22(6):623–638. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westen D, Shedler J, Durrett C, Glass S, Martens A. Personality diagnoses in adolescence: DSM-IV Axis II diagnoses and an empirically derived alternative. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:952–966. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, De Clercq B, De Fruyt F. Childhood antecedents of personality disorder: An alternative perspective. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(3):771–791. doi: 10.1017/S095457940900042X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Simonsen E. Alternative dimensional models of personality disorder: Finding a common ground. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19(2):110–130. doi: 10.1521/pedi.19.2.110.62628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: Shifting to a dimensional model. American Psychologist. 2007;62(2):71–83. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright AGC, Thomas KM, Hopwood CJ, Markon KE, Pincus AL, Krueger RF. The hierarchical structure of DSM-5 pathological personality traits. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(4):951–957. doi: 10.1037/a0027669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]