Background: Interactions between the components of the divisome are crucial for cell division, but detailed knowledge is lacking.

Results: In vivo photo cross-linking revealed two main contact sites of FtsB and FtsL on FtsQ.

Conclusion: FtsQ contains an FtsB interaction hot spot.

Significance: Our results facilitate the development of protein-protein interaction inhibitors blocking cell division.

Keywords: Cell Division, Escherichia coli, Protein Complexes, Protein Cross-linking, Protein-Protein Interactions, Benzoylphenylalanine, Divisome, Photo Cross-linking

Abstract

Escherichia coli cell division is effected by a large assembly of proteins called the divisome, of which a subcomplex consisting of three bitopic inner membrane proteins, FtsQ, FtsB, and FtsL, is an essential part. These three proteins, hypothesized to link cytoplasmic to periplasmic events during cell division, contain large periplasmic domains that are of major importance for function and complex formation. The essential nature of this subcomplex, its low abundance, and its multiple interactions with key divisome components in the relatively accessible periplasm make it an attractive target for the development of protein-protein interaction inhibitors. Although the crystal structure of the periplasmic domain of FtsQ has been solved, the structure of the FtsQBL complex is unknown, with only very crude indications of the interactions in this complex. In this study, we used in vivo site-specific photo cross-linking to probe the surface of the FtsQ periplasmic domain for its interaction interfaces with FtsB and FtsL. An interaction hot spot for FtsB was identified around residue Ser-250 in the C-terminal region of FtsQ and a membrane-proximal interaction region for both proteins around residue Lys-59. Sequence alignment revealed a consensus motif overlapping with the C-terminal interaction hot spot, underlining the importance of this region in FtsQ. The identification of contact sites in the FtsQBL complex will guide future development of interaction inhibitors that block cell division.

Introduction

The Escherichia coli divisome is a macromolecular complex formed by at least 10 essential proteins that assemble at midcell in defined steps (1). When fully assembled, this complex effects cell division through synthesis of the septal wall, cell constriction, and, ultimately, cell scission. Recruitment of the proteins to midcell occurs in a concerted, hierarchical process, starting with formation of the FtsZ ring in the cytoplasm and anchoring of the ring to the inner membrane by FtsA and ZipA (2). This is followed by recruitment of the cell division proteins FtsK, FtsQ, FtsB, FtsL, FtsW, FtsI, and FtsN (in order of dependence), all of them membrane proteins (1, 3–9). The proteins FtsQ, FtsB, and FtsL play an enigmatic role in the assembly of the divisome. All three are bitopic, inner-membrane proteins with their major domains protruding in the periplasm. Together they can form a complex independent of the divisome, as shown by immunoprecipitation experiments (10). Two-hybrid analyses have suggested that FtsQ interacts with FtsA, FtsX, FtsK, FtsL, FtsB, FtsW, FtsI, FtsN, YmgF, and with itself (11–17). On the basis of the same approach, FtsB has been suggested to interact with YmgF and FtsL with FtsK, FtsW, and YmgF (12, 13, 16, 17). The FtsQBL subcomplex thus appears to connect the cytoplasmic and periplasmic events during divisome assembly through a multitude of transient interactions (2, 18).

Considering its essential nature, its low abundance (∼20–100 copies/cell), and its multiple interactions in the relatively accessible periplasm, FtsQ is a particularly attractive target for the development of inhibitors of protein-protein interactions that block bacterial cell division (19, 20). Importantly, the three-dimensional structure of the large periplasmic domain of FtsQ has been solved, facilitating structure-based drug design (21). The periplasmic domain is essential both for FtsQ localization and for recruitment of downstream cell division proteins to the divisome (22–24). It consists of two domains, designated α and β (Fig. 1A). The α domain is located directly downstream from the membrane-spanning domain and corresponds to a so-called POTRA motif that has been implicated in transient protein interactions in transporter proteins (21). This domain is believed to be required for recruitment of FtsQ by FtsK (21, 24). The β domain is located at the C terminus and has been suggested to be involved in multiple other interactions (21).

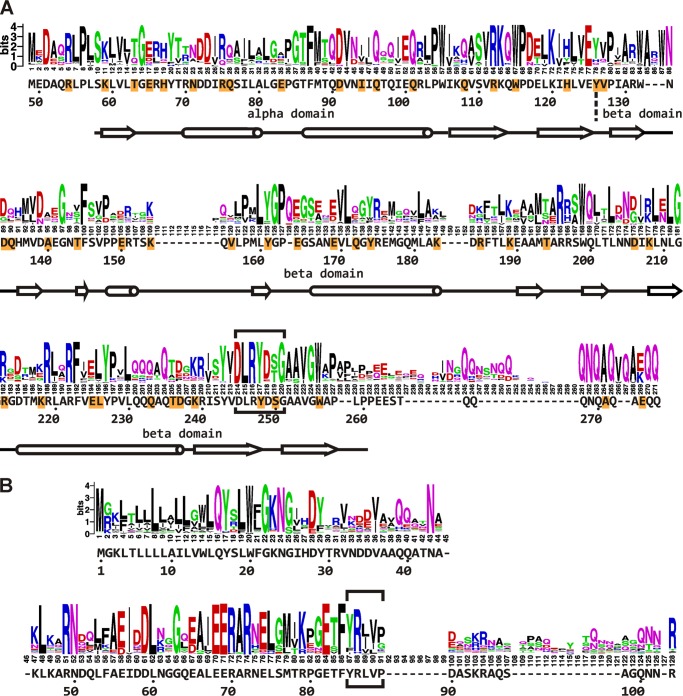

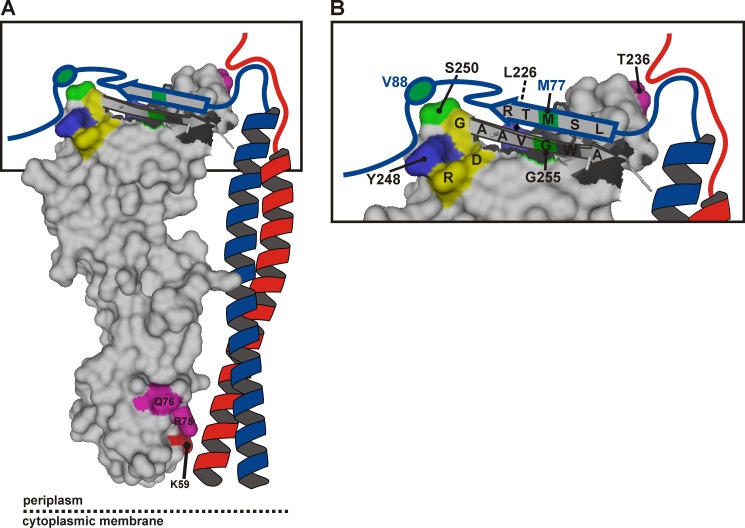

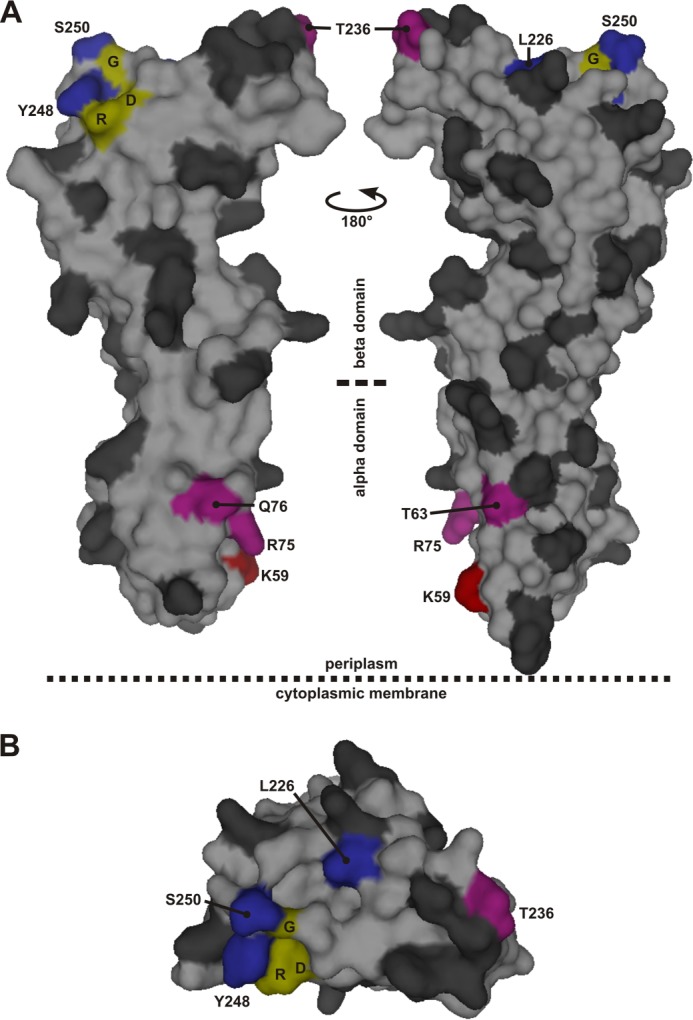

FIGURE 1.

Residues in the periplasmic domain of FtsQ substituted by the cross-linking residue Bpa. The residues that were individually substituted by Bpa are indicated in the surface plot of the structure of FtsQ amino acids 58–260 in dark gray with the following exceptions. Red, position that showed cross-linking biased toward FtsL; blue, position that showed cross-linking biased toward FtsB; purple, position that showed apparently equal cross-linking to both FtsB and FtsL. Three residues, Asp-245 (D), Arg-247 (R), and Gly-251 (G), fully conserved among 246 FtsQ proteins from Gammaproteobacteria are indicated in yellow. A, two side views. B, top view from the supposed peptidoglycan/outer membrane side. The surface plot was created in PyMOL using PDB code 2VH1.

FtsB and FtsL are small (103 and 121 residues, respectively), bitopic, inner-membrane proteins with a topology similar to FtsQ. In the absence of FtsQ, they interact, presumably, through coiled-coil regions because both proteins contain a leucine zipper motif in their periplasmic domain (25). The C-terminal regions of FtsB and FtsL are believed to interact with the C-terminal β domain of FtsQ, although the exact interaction interface is unknown (21, 26, 27). Two-hybrid analyses indicate interaction sites with other cell division proteins within the same region (11, 14, 15).

In this study, we characterized the architecture of this oligomeric FtsQBL complex in its natural environment, the E. coli inner membrane. An extensive in vivo study using site-specific incorporation of an unnatural photo cross-linking residue at defined positions in FtsQ allowed us to probe its interaction interfaces with FtsB and FtsL at the amino acid level. Our data do not correspond to results obtained in two-hybrid assays (11, 14) and indicate a hot spot for interaction with FtsB in a conserved region around residue Ser-250 at the distal end of the β domain. In addition, interactions with both FtsB and FtsL were found clustered in a membrane-proximal part of the α domain.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

E. coli strains BL21 (DE3), LMC531 (ftsQ1[Ts]) (28), and NB946 (8) were grown in TY medium (10 g of trypton, 5 g of yeast extract, 5 g of NaCl/liter) with shaking at 200 rpm. Strain BL21(DE3) was grown at 37 °C, and strain LMC531 was grown at 30 °C (permissive temperature) or at 37 °C (non-permissive temperature). When required, arabinose was used at 13 mm, glucose at 22 mm, rhamnose at 1 mm, ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, chloramphenicol at 30 μg/ml, kanamycin at 25 μg/ml, and spectinomycin at 50 μg/ml.

Construction of FtsB and FtsL Expression Vectors

Standard PCR and cloning techniques were used for DNA manipulation. The E. coli MC4100 ftsB and ftsL genes were cloned into multiple cloning site 1 (NcoI-BamHI) and multiple cloning site 2 (NdeI-BglII), respectively, of the pCDFDuet vector (Novagen), resulting in vector pCDF-ftsBL. To enrich the adenine and thymine content of the DNA in the 5′ end of the ftsL gene, the second to fifth codons of FtsL, 5′-ATCAGCAGAGTG-3′, were mutated to 5′-ATTAGTAGAGTT-3′ (silent mutations) or to 5′-ATTAATAAATTA-3′ resulting in vectors pCDF-ftsBLsat and pCDF-ftsBLmat, respectively. The latter vector encodes FtsL S3N R4K V5L.

Construction of FtsQSH8 Cross-linking Mutant Expression Vectors

DNA encoding a fusion of FtsQ with an amino-terminal StrepII-His8 dual tag was synthesized by PCR and cloned into the p29SEN vector (29), resulting in p29SENX-SH8ftsQ. Amber codons were introduced using overlap PCR. All SH8ftsQ variants were cloned into the pMedium vector (rhamnose-controlled expression, Xbrane Bioscience), resulting in pMed-SH8ftsQ and derivative amber codon mutants.

Functionality of FtsQSH8 Cross-linking Mutants

E. coli LMC531 cells harboring vector pSUP-BpaRS-6TRN (amber suppressor system) (30) and one of the pMed-SH8ftsQ variants were grown overnight at 30 °C in medium supplemented with 55 mm glycerol. The same medium without or containing 0.5 mm of the photo cross-linking amino acid p-benzoyl-L-phenylalanine (Bpa)2 (H-p-Bz-Phe-OH, Bachem) was inoculated 1:500 with the overnight cultures and incubated for 5 h at 37 °C. No rhamnose was added to the medium. The cells were fixed by addition of formaldehyde to 3.6% and incubation at ambient temperature for 15 min. Subsequently, the cells were harvested and resuspended in PBS. Cell morphology was examined by phase-contrast microscopy.

To examine the dominant negative effect of FtsQSH8 Y248*, E. coli LMC531 cells harboring vector pMedium, pMed-SH8ftsQ, or pMed-SH8ftsQ 248amber were grown overnight at 30 °C in medium supplemented with 55 mm glycerol. The same medium without or 1 mm L-rhamnose was inoculated 1:500 with the overnight cultures and incubated for 5 h at 30 °C. The cells were treated further as described above.

Photo Cross-linking and Purification of FtsQSH8

E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells harboring vectors pSUP-BpaRS-6TRN, pCDF-ftsBLmat, and one of the p29SENX-SH8ftsQ variants were grown in 25 ml of growth medium, and when an A600 of ∼0.3 was reached, Bpa was added to 0.5 mm. After 20 min of continued growth, isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to 0.5 mm, and the cells were grown for a further 1.5 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 25 ml of PBS. The cell suspension was exposed to 1.5 J/cm2 of 365-nm light (taking ∼5 min) in 12 × 12-cm dishes in a Bio-Link BLX-365 (Vilber Lourmat). The cells were harvested and resuspended in 6 ml of PBS containing 1 mm of PMSF. The cells were disrupted by a single passage through a One Shot cell disruptor (Constant Systems) at 2.14 kbar. After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was centrifuged at 293,000 × g for 45 min at 4 °C. The resulting membrane pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of 100 mm NaH2PO4, 1 m NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, 8 m urea, 1% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (pH 8.0, NaOH). After overnight incubation at ambient temperature (agitated), 50 μl of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) was added, and the suspension was incubated at ambient temperature (agitated) for a further 2 h. The nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads were washed three times with 1 ml of 100 mm NaH2PO4, 1 m NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 8 m urea, 0.2% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside (pH 8.0, NaOH), followed by elution with 80 μl of 100 mm NaH2PO4, 1 m NaCl, 300 mm imidazole, 8 m urea, 0.2% (w/v) n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside.

Detection and Crude Quantitation of Cross-linking Adducts

Proteins eluted from the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting for detection of adducts or by colloidal Coomassie staining for crude quantitation. On immunoblot FtsQ, FtsB and FtsL were detected using affinity-purified polyclonal rabbit antibodies. Colloidal Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels were scanned on a gel scanner (Bio-Rad GS-800 calibrated densitometer). Using ImageJ software (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health), a profile of each lane along the electrophoresis path was plotted. To crudely determine the relative amount of protein, the surface of a peak in the profile was approximated by a triangular shape and corrected for local background. To calculate the fraction of cross-linked FtsQSH8, the amounts of adduct were corrected for the contribution of FtsB and FtsL to the staining (according to protein mass, FtsQSH8 = 34.2/45.8 × FtsQSH8-FtsB and FtsQSH8 = 34.2/47.8 × FtsQSH8-FtsL).

Cysteine Cross-linking

Codons resulting in FtsQ Q232C, FtsQ G255C, FtsQ S250C, FtsB S76C, FtsB M77C, FtsB T78C, and FtsB V88C were introduced using overlap PCR. The SH8ftsQ variants were cloned into the p29SENX-SH8ftsQ vector. The ftsB variants were cloned into the pCDF-ftsBLmat vector. The FtsB mutants were shown to be functional by complementation of the E. coli FtsB depletion strain NB946 (expressing the ftsB mutants from vector pSAV057 (31)). The FtsQSH8 mutants were shown to be functional by complementation of the E. coli strain LMC531. E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells harboring combinations of the p29SENX-SH8ftsQ and pCDF-ftsBLmat vectors were grown in 25 ml of growth medium to an A600 of ∼0.7. After addition of isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside to a concentration of 0.02 mm, the cells were incubated for an additional 30 min. Cells were harvested, resuspended in 12.5 ml of PBS containing 50 mm of EDTA and 20 mm of N-ethylmaleimide and incubated for 10 min at ambient temperature. The cell samples were prepared for analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting, omitting the reducing agent.

FtsQ and FtsB Amino Acid Sequence Alignment

The NCBI protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was used to find 250 protein amino acid sequences in the non-redundant protein sequence database limited to the taxid 1236 set (Gammaproteobacteria) using the E. coli K12 FtsQ sequence (UniProt P06136) as a query sequence. From the resulting 250 hits, four truncated sequences were removed. The remaining 246 hits were aligned using the NCBI Constraint-based Multiple Protein Alignment Tool. From the alignment, a sequence logo was created using the weblogo.berkeley.edu tool (32). Similarly, for FtsB, the NCBI protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool was used to find 250 protein amino acid sequences in the non-redundant protein sequence database limited to the taxid 1236 set using the E. coli K12 FtsB sequence (UniProt P0A6S5) as a query sequence. From the resulting 250 hits, nine truncated sequences and one sequence that apparently resulted from a frameshift were removed. The remaining 240 hits were aligned as described above.

RESULTS

Photo Cross-linking Approach

To determine the protein-protein interaction sites of E. coli FtsQ, an in vivo cross-linking technique was used (33). An orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair enables the incorporation of Bpa at a specific site encoded in the ftsQ gene by an amber codon (TAG). Upon synthesis of the photo probe-modified mutant of FtsQ, the cells were irradiated with long-wave UV light to activate the probe. This induces a covalent link between FtsQ and any protein that is in close (≤ 3.1 Å) proximity of the photo probe (34). Guided by the crystal structure of the periplasmic domain of E. coli FtsQ, we selected 50 surface-exposed positions throughout the periplasmic domain for analysis of molecular contacts using this approach (Fig. 1) (21). Together, this analysis provides an extensive coverage of the FtsQ periplasmic surface, considering that approximately every fifth residue is modified.

Initially, we attempted to determine the FtsQ interactome by expressing His-tagged photo cross-linking FtsQ mutants at near endogenous levels as bait and the endogenous interacting proteins as prey. Although we achieved the required low-level expression of the photo cross-linking FtsQ mutants, we did not succeed in affinity-purifying the protein to a degree we would consider sufficient for reliable identification of adducts by mass spectrometry or for immunodetection of the known interaction partners FtsK, FtsB, and FtsL. It should be noted that, roughly estimated at 20 to 100 copies/cell, the endogenous level of FtsQ is very low (19, 20) and that the cross-linking efficiency typically does not exceed 40% (35, 36). We therefore decided to focus on the interactions of FtsQ with its main, biochemically verified interaction partners FtsB and FtsL upon induced expression of the three proteins.

Expression of FtsB and FtsL

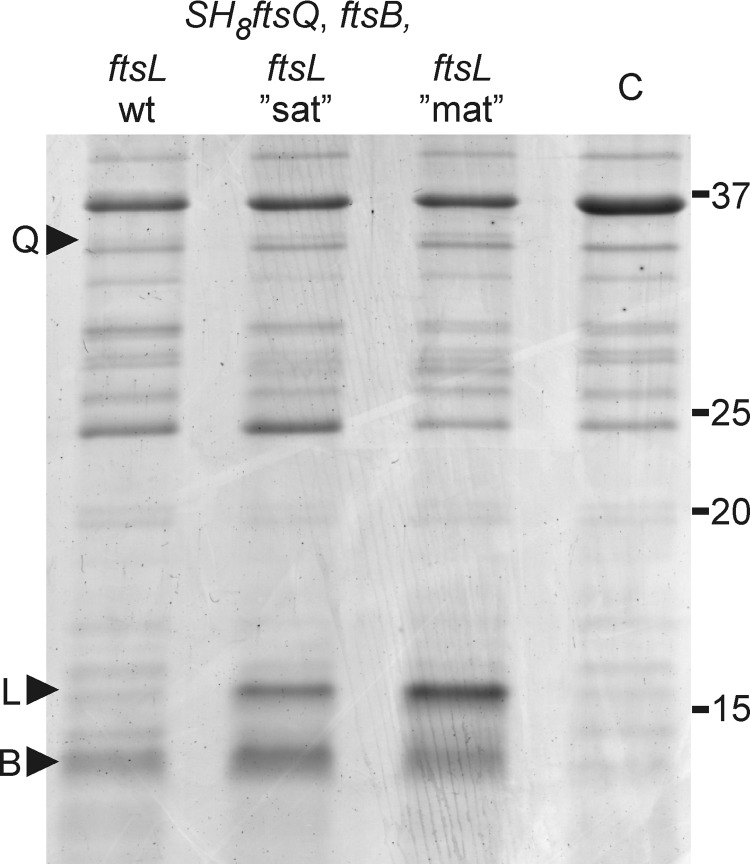

To attain tunable expression of full-length FtsB and FtsL, the corresponding genes were coexpressed from a T7 Duet vector. Upon induction, FtsB could be clearly distinguished in the membrane fraction of cells upon SDS-PAGE followed by total protein staining (Fig. 2). In comparison, FtsL was expressed at a much lower level and could only be detected by Western blotting. This disproportionate expression of FtsL relative to FtsB is undesirable because it might induce the formation of aberrant complexes and potentially bias photo cross-linking of FtsQ toward FtsB. In an attempt to optimize FtsL expression, we increased the adenine and thymine content of the first four codons following the start codon of ftsL (37). An increase from the wild-type 50% adenine and thymine to 75% by silent mutations resulted in a significant increase in the cellular level of FtsL (Fig. 2). Increase to 100% adenine and thymine, resulting in three conservative amino acid mutations (S3N, R4K, and V5L), yielded a further increase in protein level, bringing it in balance with the level of FtsB (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Expression of FtsQSH8, FtsB, and FtsL in E. coli BL21 (DE3). Membrane fractions isolated from cells expressing FtsQSH8, FtsB, and FtsL from vectors harboring the indicated genes were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. The membrane fractions were obtained following the photo cross-linking procedure (see “Experimental Procedures”), omitting the addition of Bpa. ftsL“sat”, ftsL mutant in which the second to fifth codon are enriched in adenine and thymine from 50% to 75% by silent mutations; ftsL“mat”, ftsL mutant in which the second to fifth codon are enriched in adenine and thymine from 50% to 100% encoding FtsL S3N R4K V5L; C, membrane fraction from cells harboring control vectors; Q, FtsQSH8; L, FtsL; B, FtsB. Numbers indicate molecular weight markers (kDa).

Functionality of FtsQ Cross-linking Mutants

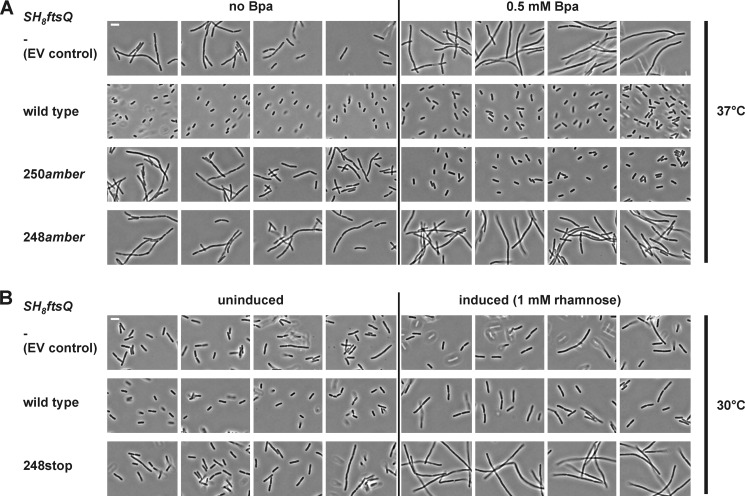

Functionality of the Bpa mutants of FtsQ was tested by low-level expression of the mutant proteins in the E. coli strain LMC531, an ftsQ temperature-sensitive mutant. Cells harboring a suppressor vector and a vector encoding StrepII-His8-FtsQ (FtsQSH8) with an amber mutation at one of the 50 selected positions were grown at the non-permissive temperature in the absence or presence of Bpa. It should be noted that, even in the presence of Bpa, significant amounts of truncated FtsQSH8 are produced because the amber codon is only partially suppressed (supplemental Fig. S1). Control cells harboring the empty pMedium vector were filamentous under both conditions, indicating that cell division was affected. In contrast, cells harboring the FtsQSH8 expression vector showed no defect in cell division, irrespective of the presence of Bpa in the growth medium, confirming that the tagged but further unmodified FtsQSH8 is functional (Fig. 3A). All FtsQSH8 mutants with an amber mutation downstream of position 250 complemented growth under both conditions. This latter observation probably reflects the functionality of longer truncated FtsQ, which is consistent with published data (38). Functionality of the full-length FtsQSH8 mutants W256Bpa, A271Bpa, and E274Bpa could, therefore, not be confirmed. With one exception discussed below, Bpa-dependent complementation was observed for all mutants with an amber mutation up to position 250, indicating that modifications of surface residues are generally permitted.

FIGURE 3.

FtsQSH8 Y248Bpa is not functional. A, FtsQ temperature-sensitive E. coli strain LMC531 harboring a Bpa-specific suppressor vector and a vector for the expression of SH8ftsQ, as indicated, were grown at the non-permissive temperature (37 °C) in the absence or presence of Bpa. Bpa-dependent complementation was observed with position 250 of FtsQSH8 encoded by an amber codon (SH8ftsQ 250amber), indicating that mutant FtsQSH8 S250Bpa is functional. No complementation was observed with the similarly encoded position 248. B, E. coli strain LMC531 harboring a vector encoding wild-type FtsQSH8 (SH8ftsQ wild type) or FtsQSH8 Y248* (SH8ftsQ 248stop) were grown at the permissive temperature (30 °C) under non-inducing and inducing conditions. Rhamnose-induced expression of FtsQSH8 Y248* inhibited cell division, indicating a dominant negative effect as described previously (24, 38). EV, empty vector. Scale bars = 4 μm.

FtsQSH8 with the amber mutation at position 248 failed to complement LMC531 (Fig. 3A). FtsQ truncates, including FtsQ Y248*, have been shown to be dominant negative in temperature-sensitive strains grown at the permissive temperature (24, 38). The observed failure to complement the temperature-sensitive strain could indicate that full-length protein FtsQSH8 Y248Bpa is not functional or that expression of the FtsQSH8 Y248* truncate has a dominant negative effect on growth. Indeed, high-level (rhamnose-induced) expression of FtsQSH8 Y248* in the absence of the amber suppression system inhibited cell division of LMC531 at the permissive temperature (Fig. 3B). However, low-level (uninduced) expression, as used in the complementation assay (supplemental Fig. S2), did not inhibit cell division. Because no dominant negative effect was observed with any of the other mutants, we conclude that most likely the FtsQSH8 Y248Bpa mutant is not functional.

UV Cross-linking at 50 Positions in FtsQ

With only one of the 50 photo cross-linking mutants shown to be non-functional, three mutants (W256Bpa, A271Bpa, and E274Bpa) not confirmed, and 46 mutants functional, the Bpa substitution of surface-exposed residues appears to be well tolerated in the periplasmic domain of FtsQ. All 50 mutants were, therefore, included in the in vivo photo cross-linking analysis to map the contact sites of FtsQ with FtsB and FtsL.

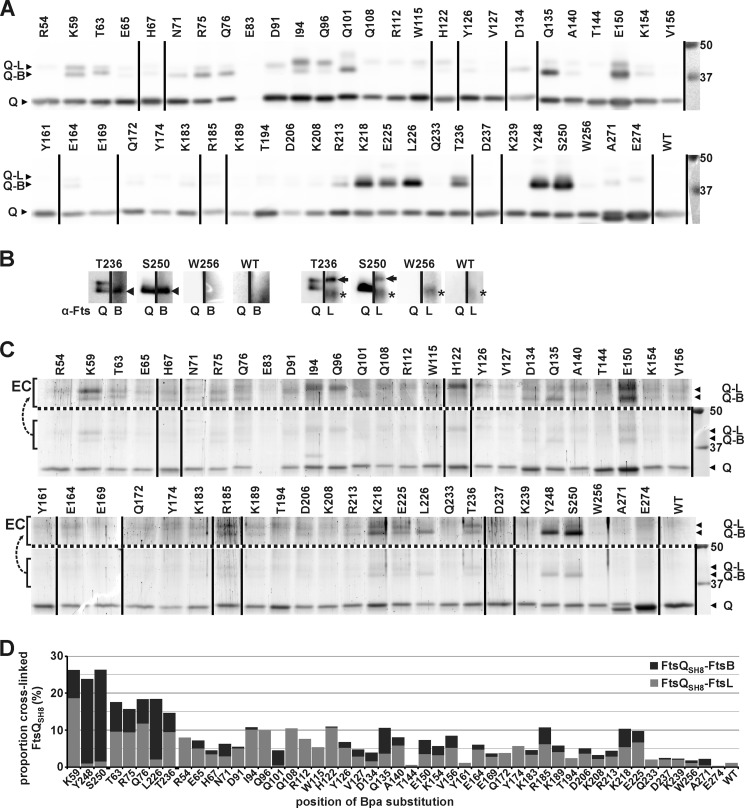

Cells expressing FtsB, FtsL, and one of the 50 FtsQSH8 Bpa mutants or unmodified FtsQSH8 were irradiated with UV light at 365 nm. The irradiated cells were lysed, and the tagged protein was purified from the membrane fraction under denaturing conditions as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cross-linking was analyzed by SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting or colloidal Coomassie staining (Fig. 4). The entire cross-linking procedure was repeated with similar results as judged by Western blot analysis. Remarkably, FtsQSH8 E83Bpa was only detectable in long exposures of the Western blot (not shown), indicating that it is expressed at very low levels that yet appear sufficient to complement cell division of the temperature-sensitive strain. Possibly, this FtsQ mutant is unstable at higher expression levels and was therefore excluded from further analysis. In the other samples, the full-length protein and cross-linking adducts were clearly detected both by immunodetection using FtsQ50–276-specific antibodies and by colloidal Coomassie staining. Appearance of the adducts was shown to be Bpa- and UV-dependent, confirming that they represent genuine cross-linked products (supplemental Fig. S3). The mobility of the cross-linking adducts in SDS-PAGE corresponded to the expected masses of an FtsQSH8-FtsB adduct (46 kDa) and of an FtsQSH8-FtsL adduct (48 kDa). In agreement with these predictions, FtsB-specific and FtsL-specific antibodies recognized the adduct of higher mobility and the adduct of lower mobility, respectively (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, at most of the positions, cross-linking to both FtsB and FtsL is detected to one of the two proteins exclusively, indicative of some flexibility in the complex or a heterogeneous population of FtsQBL complexes. The separation of the two adducts upon SDS-PAGE allowed us to quantify the relative amounts of the two distinct cross-linking products. Surprisingly, a discrepancy between the immunodetection signals and the Coomassie staining is observed (compare Fig. 4, A and C). For unknown reasons, the FtsQSH8-FtsB adducts appear to lead to disproportionally intense signals when detected using FtsQ-specific antibodies. Therefore, only the Coomassie-stained gel was used for quantitation.

FIGURE 4.

Cross-links between FtsQSH8 and FtsB and FtsL. After exposure of cells expressing FtsB, FtsL, and an FtsQSH8 Bpa substitution mutant to UV, FtsQSH8 was purified under denaturing conditions. The residue substituted by Bpa is indicated. The sample from cells expressing the parental SH8ftsQ gene is indicated by WT. A, detection by Western blotting using FtsQ-specific antibodies. Full-length FtsQSH8 and Bpa variants (Q) and two adducts, identified in B as FtsQSH8-FtsB (Q-B) and FtsQSH8-FtsL (Q-L), were detected. B, detection by Western blotting using FtsQ-specific antibodies (α-FtsQ) on one half of a lane and FtsB-specific antibodies (α-FtsB) or FtsL-specific antibodies (α-FtsL) on the other half of the same lane to identify the two adducts recognized by α-FtsQ. The FtsQSH8-FtsB adduct (arrowhead), the FtsQSH8-FtsL adduct (arrow), and an aspecific signal (asterisk) are indicated. C, to crudely quantitate the amounts of full-length FtsQSH8, FtsQSH8-FtsB and FtsQSH8-FtsL, the proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were stained with colloidal Coomassie. The proteins are indicated as in A. To enhance the visibility of the adducts, the region containing these proteins is duplicated above the dotted line with enhanced contrast (EC). The lower region of these gels showing truncated FtsQSH8 as well as full-length FtsQSH8 is shown in supplemental Fig. S2. D, from the crude quantitation of the amounts of FtsQSH8, FtsQSH8-FtsB, and FtsQSH8-FtsL, the proportion of cross-linked FtsQSH8 was calculated. The proportion is divided into FtsQSH8-FtsB and FtsQSH8-FtsL, which are indicated in dark gray and light gray, respectively. In A and C, two identically treated Western blots and two identically treated gels, respectively, were combined, and the lane order was rearranged as indicated by vertical lines. On the right, the protein standard and corresponding molecular weight (kDa) are shown.

The highest cross-linking efficiencies, ∼25%, were obtained at positions 59, 248, and 250 (Fig. 4D). At these positions a clear bias toward either FtsB (248 and 250) or FtsL (59) was observed. In a second group, with cross-linking efficiencies between ∼15 and 20%, only position 226 showed a similar bias toward FtsB. Positions 63, 75, 76, and 236 cross-linked to FtsB and FtsL with similar efficiency. Taken together, these results indicate a stable and specific contact site in the β domain around position 250 of FtsQ for FtsB and in the α domain at position 59 for FtsL.

FtsQ Residues Ser-250 and Gly-255 Are in Close Proximity to FtsB Residues Val-88 and Met-77, Respectively

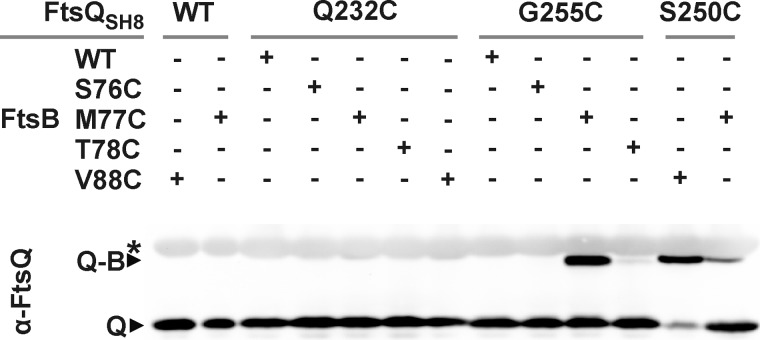

Photo cross-linking indicated marked FtsB-FtsL contact sites in the three-dimensional structure of the periplasmic domain of FtsQ. The data, however, do not reveal which regions of FtsB and FtsL form the complementary side of the protein-protein interface. We compared our results with two structural models for the FtsQBL complex that were presented in a bioinformatics study (39). On the basis of the crystal structure of FtsQ and the limited biochemical information from literature, a heterotrimeric model and a heterohexameric model were obtained. The trimeric model is not in agreement with our photo cross-linking data. Of the eight positions that cross-linked with relatively high efficiency, only one (position 76) matches the model. Bpa at this position showed no bias toward cross-linking FtsB or FtsL, whereas the model would predict a strong bias toward FtsB. The hexameric model is more consistent with our data. Cross-linking efficiencies and biases at positions 59, 63, 226, 248, and 250 correspond reasonably well with this model. Importantly, in this model, the region in FtsB from residue Tyr-85 to Asp-90, which has been suggested to be required for interaction with FtsQ (26), is in close proximity to three positions (226, 248, and 250) that showed relatively efficient cross-linking to FtsB. To further examine predicted interaction interfaces, we introduced single cysteines in the relevant regions of the partner proteins. Juxtaposed cysteines in FtsQ and FtsB are expected to form disulfide bonds in the oxidative periplasm, offering independent spatial information on the interacting regions. The following positions in FtsQ and FtsB were selected and combined: position 250 in FtsQ and position 88 in FtsB on the basis of the hexameric model and centrally positioned in the suggested FtsQ interaction domain; positions 76, 77, and 78 in FtsB and position 232 in FtsQ on the basis of the hexameric model; and positions 76, 77, and 78 in FtsB and position 255 in FtsQ on the basis of the trimeric model.

All cysteine substitution mutants of FtsQ were shown to be functional in the FtsQ temperature-sensitive strain grown at the non-permissive temperature. Likewise, all cysteine substitution mutants of FtsB were shown to complement depletion of FtsB in a conditional FtsB mutant (data not shown). For cross-linking analysis, cells expressing ftsL together with different combinations of the ftsQ and ftsB cysteine mutants were harvested and prepared for SDS-PAGE. On Western blot analysis, FtsQ was detected using FtsQ-specific antibodies (Fig. 5). Strikingly, disulfide bond formation appeared restricted to the FtsQ-FtsB combinations 250C-88C, 255C-77C, and 250C-77C. The efficiency of disulfide bond formation in the 250C-77C pair appeared to be substantially lower than in the other two pairs. Considering the two structural models obtained by Villanelo et al. (39), the results are ambivalent. The 250C-88C combination matches with the hexameric model, and the 255C-77C combination matches with the trimeric model. The disulfide bond formation between FtsB position 77 (but not 76 and 78) and position 255 in FtsQ might indicate a close and specific contact between these residues of FtsQ and FtsB. Interestingly, cross-linking between FtsQ 250C and FtsB 88C suggests direct contact between the FtsB interaction region of FtsQ (inferred from our photo cross-linking results) and the FtsQ interaction region of FtsB suggested by Gonzalez and Beckwith (26).

FIGURE 5.

FtsQ residues 250 and 255 are in close proximity to FtsB residues 88 and 77, respectively. The proximity of positions 232, 250, and 255 in FtsQ and positions 76, 77, 78, and 88 in FtsB was analyzed by cysteine cross-linking. Samples of cells expressing FtsL together with different combinations of FtsQ and FtsB variants, as indicated, were subjected to non-reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using FtsQ-specific antibodies. Q, FtsQSH8; Q-B, FtsQSH8-FtsB adduct; asterisk, aspecifically detected bands.

The FtsB Binding Site Overlaps with a Consensus Motif

The region around residue 250 in FtsQ appears to be of central importance for the interaction with FtsB and FtsL. First, truncating the C terminus down to residue Trp-256 does not abolish the function of the protein, whereas truncation by a further six residues does (24, 38). Second, in contrast to at least 46 other surface-exposed positions in the periplasmic domain of FtsQ, the Bpa substitution at position 248 abolished the function of FtsQ. Surprisingly, this mutant efficiently cross-linked FtsB, indicating that the interaction with FtsB was not affected. Third, two other positions in this area, 226 and 250, efficiently photo cross-linked to FtsB (Fig. 4). Fourth, we observed that a cysteine introduced at position 250 of FtsQ is sufficiently close to a cysteine introduced at position 88 of FtsB so that a disulfide bond is formed (Fig. 5). To examine the conservation of the residues in this region of FtsQ among close orthologs, we made an alignment of 250 protein sequences that were found within the Gammaproteobacteria class in a basic local alignment search using the E. coli K12 FtsQ sequence as query (Fig. 6). Four sequences, derived from shotgun sequencing, did not contain the region of interest because of an incomplete open reading frame. The remaining 246 sequences contained a strong consensus motif, DLRY(d/e)(s/t)G, in the region of interest (E. coli K12 FtsQ residues 245 to 251). The Asp, Arg, Tyr, and Gly are fully conserved. One protein contains a methionine at the second position instead of a leucine. 86% of the proteins contain an aspartate at the fifth position and 7% a glutamate. At the sixth position, 54% contain a serine and 42% a threonine. The four fully conserved residues are adjacent in the E. coli FtsQ structure (Fig. 1). In this structure, Asp-249 has a polar contact with Arg-219, another highly conserved residue. Arg-219 is 99.6% conserved, with one protein containing a lysine at the corresponding position. This network of consensus motif and conserved residues may extend to the fully conserved glycine Gly-212 adjacent to Arg-247 and Arg-219. In contrast to Tyr-248 and Ser-250, the nearby position 226, where biased cross-linking to FtsB was observed, showed relatively low conservation (87% Leu, 5% Val, 3% Ile, 2% Ala, 0.4% Ser) and does not appear to be part of the network of conserved residues.

FIGURE 6.

Sequence logos representing alignments of Gammaproteobacterial homologs of E. coli K12 FtsQ and FtsB. A, a sequence logo was generated from an alignment of 246 Gammaproteobacterial homologs of E. coli K12 FtsQ, of which the periplasmic domain part is shown. The E. coli K12 FtsQ residues, numbering, and secondary structures (tube, α helix; arrow, β sheet) are indicated underneath the sequence logo. Residues substituted by Bpa for photo cross-linking are highlighted in orange. The consensus motif DLRY(d/e)(s/t)G is boxed. B, similar to A, an alignment of 240 Gammaproteobacterial homologs of E. coli K12 FtsB. The FtsQ interaction domain suggested by Gonzalez and Beckwith (26) is boxed.

A similar alignment was made for FtsB. The region in E. coli FtsB from residue Tyr-85 to Asp-90 implicated in FtsQ interaction (26) is more variable than the consensus motif in FtsQ. Interestingly, the adjacent Glu-82 and Phe-84 are fully conserved. A bit further upstream of this position, the Gammaproteobacterial FtsB sequences harbor a consensus motif EERAR (E. coli FtsB residues 68–72). This motif is at the C-terminal end of the α-helical structure predicted for E. coli FtsB (39). These highly conserved residues may be involved in the interactions of FtsB with FtsQ and FtsL and/or with other divisome proteins in Gammaproteobacteria.

DISCUSSION

The FtsQBL complex plays an essential role in the E. coli cell division process. Thus far, biochemical data have provided only a very crude indication of the interactions that form this protein complex. With the cross-linking and alignment data presented in this report, we have delineated a site in the α domain near the cytoplasmic membrane and a site in the distal end of the β domain of E. coli FtsQ where FtsB and FtsL bind.

At many of the sites where substantial cross-linking occurred, both FtsQ-FtsB and FtsQ-FtsL adducts were observed, indicating cross-linking from one position in FtsQ to both interacting proteins. This might be related to the predicted FtsB-FtsL coiled-coil heterodimer and dynamics within the FtsQBL complex or to heterogeneity in the population of complexes. Interestingly, no FtsQ-FtsQ cross-linking was detected. The oligomeric state of FtsQ is unclear, with contradicting results being reported. Oligomerization is suggested by two-hybrid analysis and coimmunoprecipitation experiments (14, 15). Other coimmunoprecipitation experiments, premature targeting, and analytical ultracentrifugation, however, indicate a monomeric state (21, 40, 41). Our data appear inconsistent with the existence of an FtsQ dimerization region in the periplasmic domain. However, we cannot exclude that the cytoplasmic or membrane-spanning part of FtsQ contributes to dimer formation.

On the basis of the cross-linking data, two hot spots in the periplasmic domain of FtsQ were identified for the interaction with FtsB and FtsL, one in the α domain around residue 75 and one in the distal part of the β domain around residue 250. It should be taken into consideration that Bpa has been shown to display some degree of chemoselectivity (34, 42). Wittelsberger et al. (43) have shown that a Bpa residue in the parathyroid hormone receptor reacts with introduced methionine residues in the parathyroid hormone over a range of 11 amino acids. This effect is possibly due to the capture of diverse states resulting from high reactivity of Bpa with methionine and considerable conformational flexibility. Although the selectivity of Bpa under our in vivo conditions is not known, the specific cross-linking pattern throughout the periplasmic domain of FtsQ, with considerable differences between neighboring positions, argues against extensive selectivity and/or flexibility. Another indication for the specificity of the interactions is found in the cysteine cross-linking results. Although a cysteine at position 77 of FtsB readily cross-links with FtsQ G255C, the two neighboring positions do not, indicating an oriented and specific interaction between these sites. Moreover, no effect of high reactivity of Met-77 in FtsB was observed with the FtsQ Bpa mutants in proximity of position 255 (positions 206, 208, 239, and 256). In fact, these four positions all exhibited low cross-linking efficiencies. Taken together, these observations indicate that the contact between FtsQ and FtsB around positions 255 and 77, respectively, is specific and rigid.

Recently, Villanelo et al. (39) reported that in their molecular dynamics simulation, FtsQ residues 251–258 and FtsB residues 76–88 formed a stable, β sheet-like interaction through several hydrogen bonds that diminished the flexibility in that zone. Although the FtsQ 255C-FtsB 77C cross-linking corresponds well with this model, the FtsQ 250C-FtsB 88C cross-linking appears inconsistent with its parallel β sheet-like interaction. Therefore, an alternative model should be considered in which these regions indeed form a β sheet-like interaction but in an anti-parallel orientation (Fig. 7). The less efficient FtsQ 250C-FtsB 77C cross-linking does not support a particular orientation. Cross-linking of FtsQ 250C to both FtsB 88C and 77C may again be indicative of some flexibility in the complex or heterogeneity in FtsQBL complexes.

FIGURE 7.

Model of the periplasmic part of the E. coli FtsQBL complex. A, a surface plot of the periplasmic domain of FtsQ exposing the C-terminal β strand in graphic style was created in PyMOL using PDB code 2VH1. The color coding is as in Fig. 1, except for the cysteine cross-linking positions FtsQ 250 and 255 and FtsB 77 and 88, here indicated in green. FtsB (blue) and FtsL (red) are drawn schematically forming a coiled-coil that contacts FtsQ in the α domain around residue 59. B, a close-up of the distal end of the model. The C-terminal regions of FtsB and FtsL are both in close proximity to residue Thr-236 of FtsQ. The C-terminal region of FtsB around residue 77 further engages in a β sheet-like interaction with the C-terminal β strand of FtsQ, whereas the region around residue 88 interacts with the hot spot on FtsQ including residues Leu-226, Tyr-248, and Ser-250. Surrounded by these extensive interactions are residues Asp-245, Arg-247, and Gly-251 (yellow) that are part of a strong consensus motif, DLRY(d/e)(s/t)G.

A β sheet-like interaction agrees with several observations and may be critical within the FtsQBL complex. Functional analysis of C-terminally truncated mutants of FtsQ indicates that residues 250–255 are essential and that the FtsQ A252P mutant, in which the presumed β strand is disrupted, is unable to recruit FtsB and FtsL (24, 38). The cysteine cross-linking data also correlate well with a β sheet-like interaction. If the side chains of the cysteines in FtsB 77C and FtsQ 255C are juxtaposed in the β sheet, allowing oxidation upon interaction, the side chains of FtsB 76C and 78C would logically be on the opposite side in an arrangement unfavorable for oxidation. In addition, the photoreactive side chain of Bpa at position 256 of FtsQ would likely be unfavorably oriented for cross-linking to FtsB, consistent with the low cross-linking efficiency observed at this position.

Adjacent to the C-terminal β strand of FtsQ is one of the cross-linking hot spots. The distinct bias in photo cross-linking toward FtsB suggests a strong and specific interaction at this site in FtsQ. Moreover, we observed disulfide bond formation between FtsQ 250C and FtsB 88C. Residues 85–90 of FtsB have been shown to be required for the interaction with FtsQ, and the C-terminal flanking region has been suggested to be involved in the interaction as well (26). Interestingly, two of the residues defining the hot spot in the β domain, Tyr-248 and Ser-250, are part of a consensus motif conserved among Gammaproteobacterial FtsQ. Substitution of the fully conserved Tyr-248 by Bpa abolished the function of FtsQ in cell division while maintaining the interaction with FtsB. This indicates that this region of FtsQ is not only involved in the interaction with FtsB but also in the interaction with other cell division proteins.

Surprisingly, bacterial two-hybrid assays have indicated that FtsQ lacking its 74 C-terminal residues (203–276) comprising the entire distal end of the β domain still interacts with FtsB (14). In these experiments, the FtsB interaction was reported to localize to FtsQ residues 136–202. In strong contrast to these data, the two cross-linking hot spots we identified flank this region. The two-hybrid assays further indicated that the interaction with FtsL is localized in the 42 C-terminal residues, whereas relatively little FtsQ-FtsL adduct was detected in this region. In addition, two-hybrid analysis indicated self-interaction of FtsQ, whereas no FtsQ-FtsQ cross-linking adduct was detected in the experiments presented here (14, 15). At present, the cause of the strong discrepancy between the results of the two techniques is unclear.

The data presented in this study provide new distance constraints to refine the models of the periplasmic region of the FtsQBL complex derived by bioinformatics analysis (39). Although our data do not closely match either one of the models, their general geometry is consistent with the photo cross-linking hot spot and the cysteine cross-linking in the distal end of the β domain of FtsQ. A simplified model that satisfies our cross-linking data is presented in Fig. 7. Biochemical evaluation of a refined model may further elucidate the structure of the FtsQBL complex.

The technique to site-specifically incorporate a photo cross-linking residue in vivo provides an excellent way to study interaction interfaces within the FtsQBL complex. The complex can be studied using minimally altered, functional, full-length proteins in their natural environment. Extending the current data with photo cross-linking from FtsB and FtsL could provide clues concerning the FtsQBL stoichiometry and test, for instance, the recently reported structural organization of FtsB in vivo within the context of the membrane-spanning complex (44). Other divisome proteins can be added to the system to probe for other interaction interfaces, for instance at the site of the conserved DLRY(d/e)(s/t)G motif. Importantly, with an increasing and urgent need for new classes of antibiotics, especially the FtsQ-FtsB interaction hot spot and the conserved region in the distal end of the β domain of FtsQ may be considered as drug target sites. A refined model of the FtsQBL complex will allow rational design of potential inhibitory compounds that may be developed into new antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter G. Schultz of The Scripps Research Institute (La Jolla, CA) for the vectors for in vivo photo-cross-linking and Jon Beckwith and Brian Meehan of Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA) for the NB946 strain and technical support.

This work was supported by European Commission Contract HEALTH-F3-2009-223431 (DIVINOCELL).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- Bpa

- p-benzoyl-L-phenylalanine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aarsman M. E., Piette A., Fraipont C., Vinkenvleugel T. M., Nguyen-Distèche M., den Blaauwen T. (2005) Maturation of the Escherichia coli divisome occurs in two steps. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1631–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vicente M., Rico A. I. (2006) The order of the ring. Assembly of Escherichia coli cell division components. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 5–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Addinall S. G., Cao C., Lutkenhaus J. (1997) FtsN, a late recruit to the septum in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 25, 303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yu X. C., Tran A. H., Sun Q., Margolin W. (1998) Localization of cell division protein FtsK to the Escherichia coli septum and identification of a potential N-terminal targeting domain. J. Bacteriol. 180, 1296–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen J. C., Weiss D. S., Ghigo J. M., Beckwith J. (1999) Septal localization of FtsQ, an essential cell division protein in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181, 521–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen J. C., Beckwith J. (2001) FtsQ, FtsL and FtsI require FtsK, but not FtsN, for co-localization with FtsZ during Escherichia coli cell division. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 395–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pichoff S., Lutkenhaus J. (2002) Unique and overlapping roles for ZipA and FtsA in septal ring assembly in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 21, 685–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buddelmeijer N., Judson N., Boyd D., Mekalanos J. J., Beckwith J. (2002) YgbQ, a cell division protein in Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae, localizes in codependent fashion with FtsL to the division site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6316–6321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mercer K. L., Weiss D. S. (2002) The Escherichia coli cell division protein FtsW is required to recruit its cognate transpeptidase, FtsI (PBP3), to the division site. J. Bacteriol. 184, 904–912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Buddelmeijer N., Beckwith J. (2004) A complex of the Escherichia coli cell division proteins FtsL, FtsB and FtsQ forms independently of its localization to the septal region. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1315–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grenga L., Guglielmi G., Melino S., Ghelardini P., Paolozzi L. (2010) FtsQ interaction mutants. A way to identify new antibacterial targets. N. Biotechnol. 27, 870–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karimova G., Robichon C., Ladant D. (2009) Characterization of YmgF, a 72-residue inner membrane protein that associates with the Escherichia coli cell division machinery. J. Bacteriol. 191, 333–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grenga L., Luzi G., Paolozzi L., Ghelardini P. (2008) The Escherichia coli FtsK functional domains involved in its interaction with its divisome protein partners. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 287, 163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. D'Ulisse V., Fagioli M., Ghelardini P., Paolozzi L. (2007) Three functional subdomains of the Escherichia coli FtsQ protein are involved in its interaction with the other division proteins. Microbiology 153, 124–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karimova G., Dautin N., Ladant D. (2005) Interaction network among Escherichia coli membrane proteins involved in cell division as revealed by bacterial two-hybrid analysis. J. Bacteriol. 187, 2233–2243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Di Lallo G., Fagioli M., Barionovi D., Ghelardini P., Paolozzi L. (2003) Use of a two-hybrid assay to study the assembly of a complex multicomponent protein machinery. Bacterial septosome differentiation. Microbiology 149, 3353–3359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dubarry N., Possoz C., Barre F. X. (2010) Multiple regions along the Escherichia coli FtsK protein are implicated in cell division. Mol. Microbiol. 78, 1088–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. den Blaauwen T., de Pedro M. A., Nguyen-Distèche M., Ayala J. A. (2008) Morphogenesis of rod-shaped sacculi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 321–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Carson M. J., Barondess J., Beckwith J. (1991) The FtsQ protein of Escherichia coli: membrane topology, abundance, and cell division phenotypes due to overproduction and insertion mutations. J. Bacteriol. 173, 2187–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weiss D. S., Pogliano K., Carson M., Guzman L. M., Fraipont C., Nguyen-Distèche M., Losick R., Beckwith J. (1997) Localization of the Escherichia coli cell division protein Ftsl (PBP3) to the division site and cell pole. Mol. Microbiol. 25, 671–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van den Ent F., Vinkenvleugel T. M., Ind A., West P., Veprintsev D., Nanninga N., den Blaauwen T., Löwe J. (2008) Structural and mutational analysis of the cell division protein FtsQ. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 110–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guzman L. M., Weiss D. S., Beckwith J. (1997) Domain-swapping analysis of FtsI, FtsL, and FtsQ, bitopic membrane proteins essential for cell division in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179, 5094–5103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buddelmeijer N., Aarsman M. E., Kolk A. H., Vicente M., Nanninga N. (1998) Localization of cell division protein FtsQ by immunofluorescence microscopy in dividing and nondividing cells of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180, 6107–6116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen J. C., Minev M., Beckwith J. (2002) Analysis of ftsQ mutant alleles in Escherichia coli. Complementation, septal localization, and recruitment of downstream cell division proteins. J. Bacteriol. 184, 695–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Robichon C., Karimova G., Beckwith J., Ladant D. (2011) Role of leucine zipper motifs in association of the Escherichia coli cell division proteins FtsL and FtsB. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4988–4992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gonzalez M. D., Beckwith J. (2009) Divisome under construction: distinct domains of the small membrane protein FtsB are necessary for interaction with multiple cell division proteins. J. Bacteriol. 191, 2815–2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gonzalez M. D., Akbay E. A., Boyd D., Beckwith J. (2010) Multiple interaction domains in FtsL, a protein component of the widely conserved bacterial FtsLBQ cell division complex. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2757–2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Taschner P. E., Huls P. G., Pas E., Woldringh C. L. (1988) Division behavior and shape changes in isogenic ftsZ, ftsQ, ftsA, pbpB, and ftsE cell division mutants of Escherichia coli during temperature shift experiments. J. Bacteriol. 170, 1533–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Genevaux P., Keppel F., Schwager F., Langendijk-Genevaux P. S., Hartl F. U., Georgopoulos C. (2004) In vivo analysis of the overlapping functions of DnaK and trigger factor. EMBO Rep. 5, 195–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ryu Y., Schultz P. G. (2006) Efficient incorporation of unnatural amino acids into proteins in Escherichia coli. Nat. Methods 3, 263–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Alexeeva S., Gadella T. W., Jr., Verheul J., Verhoeven G. S., den Blaauwen T. (2010) Direct interactions of early and late assembling division proteins in Escherichia coli cells resolved by FRET. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 384–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004) WebLogo. A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu C. C., Schultz P. G. (2010) Adding new chemistries to the genetic code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 413–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dormán G., Prestwich G. D. (1994) Benzophenone photophores in biochemistry. Biochemistry 33, 5661–5673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang M., Lin S., Song X., Liu J., Fu Y., Ge X., Fu X., Chang Z., Chen P. R. (2011) A genetically incorporated crosslinker reveals chaperone cooperation in acid resistance. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mori H., Ito K. (2006) Different modes of SecY-SecA interactions revealed by site-directed in vivo photo-cross-linking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16159–16164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Voges D., Watzele M., Nemetz C., Wizemann S., Buchberger B. (2004) Analyzing and enhancing mRNA translational efficiency in an Escherichia coli in vitro expression system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 318, 601–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Goehring N. W., Petrovska I., Boyd D., Beckwith J. (2007) Mutants, suppressors, and wrinkled colonies. Mutant alleles of the cell division gene ftsQ point to functional domains in FtsQ and a role for domain 1C of FtsA in divisome assembly. J. Bacteriol. 189, 633–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Villanelo F., Ordenes A., Brunet J., Lagos R., Monasterio O. (2011) A model for the Escherichia coli FtsB/FtsL/FtsQ cell division complex. BMC Struct. Biol. 11, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goehring N. W., Gonzalez M. D., Beckwith J. (2006) Premature targeting of cell division proteins to midcell reveals hierarchies of protein interactions involved in divisome assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goehring N. W., Gueiros-Filho F., Beckwith J. (2005) Premature targeting of a cell division protein to midcell allows dissection of divisome assembly in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 19, 127–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Deseke E., Nakatani Y., Ourisson G. (1998) Intrinsic reactivities of amino acids towards photoalkylation with benzophenone. A study preliminary to photolabelling of the transmembrane protein glycophorin A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1998, 243–251 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wittelsberger A., Thomas B. E., Mierke D. F., Rosenblatt M. (2006) Methionine acts as a “magnet” in photoaffinity crosslinking experiments. FEBS Lett. 580, 1872–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. LaPointe L. M., Taylor K. C., Subramaniam S., Khadria A., Rayment I., Senes A. (2013) Structural organization of FtsB, a transmembrane protein of the bacterial divisome. Biochemistry 52, 2574–2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]