Abstract

Background

Inadequate diagnosis and suboptimal control of hypertension is a major driver of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in Africa. Understanding the levels of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension and the associated factors has important implications for hypertension control efforts.

Methods

The PubMed database was searched for original articles related to awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Africa published between 1993 and 2013. The key search terms were: Africa, awareness, treatment, control, and hypertension. Exploration of bibliographies cited in the identified articles was done to provide further studies. Full texts of the articles were obtained from various internet sources and individual authors. A data extraction sheet was used to collect this information.

Results

Thirty eight studies drawn from 23 African countries from all regions of the continent met the inclusion criteria. The levels of awareness, treatment and control varied widely from country to country. Rural populations had lower levels of awareness than urban areas. North African countries had the highest levels of treatment in the continent. There was generally poor control of hypertension across the region even among subjects that were aware of their status and those that were treated. On the whole, the women had a better control status than the men.

Conclusion

There are low levels of awareness and treatment of hypertension and even lower levels of control. Tailored research is required to uncover specific reasons behind these low levels of awareness and treatment, and especially control, in order to inform policy formulation for the improvement of outcomes of hypertensive patients in Africa.

Keywords: Hypertension, Awareness, Control, Gender, Associated factors

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in developing countries where it causes nearly as many deaths as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis [1,2]. Africa, a continent of 53 countries and one billion people is not only beleaguered by a huge burden of infectious disease but also bears a considerable proportion of the world’s CVD burden [3]. Presently, the age-specific mortality rates from CVDs are much higher in younger age groups in both men and women in Africa than in the developed world [4]. CVD is the second leading overall cause of death in Africa, after HIV/AIDS, and is the leading cause of mortality among individuals over the age of thirty [5]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) projects that over the next ten years Africa will experience the largest increase in death rates from CVD and therefore the negative economic impact of CVD will be more felt on the continent [3].

Hypertension is the driver of the CVD epidemic in Africa where it is a major, independent risk factor for heart failure, and stroke and kidney failure [6]. The management of these complications is difficult to sustain in sub-Saharan countries where resource-intensive care is not very feasible. Insufficient diagnosis of hypertension and suboptimal blood pressure control in the diagnosed patients increases morbidity and mortality with an increased burden to health care resources [7]. In developed countries, the improved control of hypertension has led to considerable reduction in overall morbidity and mortality over the last fifty years [8,9]. Evidence from large clinical trials has shown a 40% reduction in stroke and a reduction of at least 25% in myocardial infarction associated with treatment and control of hypertension [10,11].

The increasing awareness of hypertension as an important cause of morbidity and mortality in Africa over the last twenty years has resulted in numerous publications documenting the burden of hypertension in Africa which now calls for systematic reviews to provide a comprehensive understanding of the situation in order to inform the design of tailored control and research efforts. In 2007, Addo et al. published a systematic review which showed extensively varying prevalence of hypertension with higher prevalence rates in the urban than rural areas in Sub-Saharan. There was marginal reporting on the levels of awareness, treatment or control in that publication [12]. Since then, there have been several studies conducted that have further highlighted the challenge of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension. This systematic review is therefore intended to evaluate the available data on levels of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Africa with a view of suggesting measures that could improve control among hypertensive patients.

Methods

This systematic review followed the guidelines set out by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [13]. We considered articles published in all languages between 1993 and 2013 to give a more comprehensive and current appraisal of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Africa. Journal articles in other languages were translated to English. To ensure relative homogeneity and comparability of the studies, we considered only community based cross-sectional studies that reported awareness, treatment and control of hypertension. We considered articles that defined hypertension as a measured blood pressure of >140 systolic and >90 diastolic; awareness as the prior knowledge of hypertensive status; treatment as any attempted pharmacological therapy for hypertension in patients who were aware of their status and control as a blood pressure of <140 systolic and <90 mmHg diastolic in treated hypertensive subjects. We included studies that used both automated and mercury sphygmomanometers as blood pressure measuring devices, and surveys that had a sample size of at least 350 participants. Non-pharmacological therapy is an important way of controlling hypertension and indeed a first line for pre-hypertension. However, the studies included, described only control with pharmacological therapy because this is a more demonstrable way of therapy. We excluded studies in which hypertension status was determined using one blood pressure reading.

We searched in PubMed using the key search terms: Africa, awareness, treatment, control, and hypertension. We also used individual country names for the 53 African countries and hypertension as additional key search terms to obtain articles on the subject. Eligible articles were assessed by one member of the team (JK). We excluded all studies that were hospital based and all data whose definitions of awareness, treatment and control differed from the agreed-on definitions. The abstracts of all potentially relevant papers were reviewed and full articles were accessed through Pub Med or Google Scholar or HINARI. The references of all the relevant research articles were scrutinised for additional potential data sources. The full texts of these studies were also accessed in a similar way. The authors whose full texts papers could not be accessed by the numerous internet based sources used were requested to provide them.

A data extraction sheet was used to collect information about the country, the year of publication, the number of participants, the prevalence of hypertension and the levels of awareness, treatment or control. Where the factors that predicted the levels of awareness, treatment and control were provided, these too were extracted. Where possible, results from multinational studies were disaggregated to show the status of awareness, treatment and control within individual countries. Where it was not possible to disaggregate the data by country, the study was presented as one and the countries in which the study was done were shown. In the publications considered, level of awareness was measured as a proportion of the total numbers of hypertensive subjects that were aware of their hypertensive status; level of treatment as a proportion of the subjects who were aware of their hypertensive status who were on pharmacological therapy and level of control as the proportion of treated patients who attained a blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg. The threshold statistical significance for factors that predicted hypertension was a p-value < 0.05. We also recorded odds ratios in those publications that reported them. Owing to the heterogeneity of the study designs and the lack of reported confidence intervals in most the studies, a combined analysis of the reported data could not be done.

Results

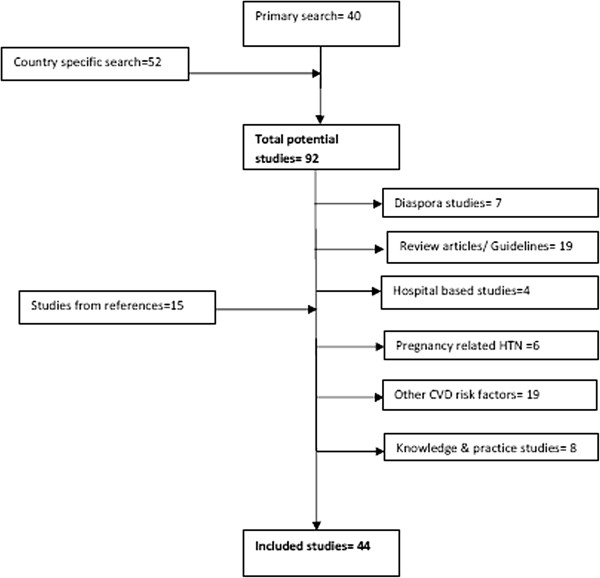

Figure 1 shows the schema of the process of choosing the studies that were included in the review. The primary PubMed search identified 40 articles. The country-specific searches led to the identification of an additional 52 studies. We excluded six studies that considered maternal hypertension; eight that described awareness as “knowledge of the effects of hypertension” rather than “awareness of hypertensive status”; 19 review papers and guidelines and 6 studies among Africans in the diaspora (living outside the continent). Fifteen additional studies were extracted from the bibliographies of the eligible articles and included for review. Eventually 44 studies were included in the review of the awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Africa.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search.

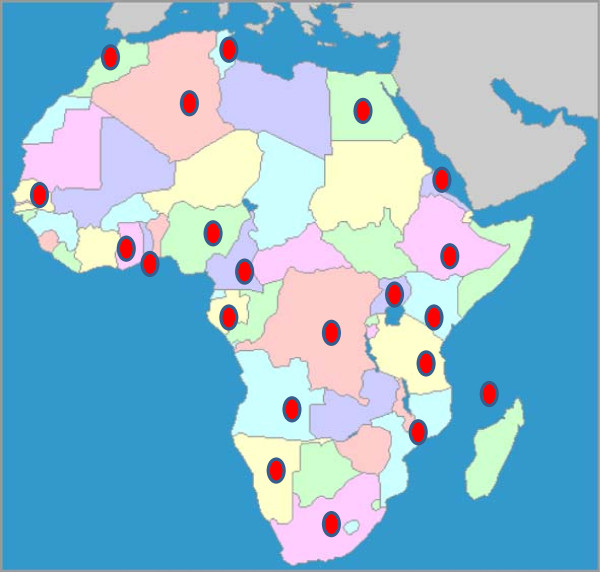

Figure 2 shows the countries on the African continent represented in the review. Overall, 26 of the 53 African countries were represented from all the regions of the continent. East Africa was represented by fourteen studies from seven countries [14-27]. Central Africa [28-33] and North Africa [34-39] were each represented by six studies. West Africa was represented by eleven studies [21,40-49]. An additional four studies from South Africa and Namibia were included in the survey [21,50-52].

Figure 2.

Map of Africa distribution of studies reviewed.

Table 1 summarises the findings of the systematic review including any factors associated with diagnosis, treatment and control where available. The populations represented in this review were diverse and included both rural and urban subjects. Two of the articles were from multinational studies [21,35]. An additional six studies were nation-wide survey [29,30,36,37,53,54]. The special communities represented in the studies were slum dwellers in Kenya, gold miners in South Africa and the market community in Nigeria [19,44,50].

Table 1.

Results of systematic review of hypertension awareness, treatment, control, and any associated factors from 44 studies in Africa, 1993-2013

|

Country |

Location |

Age range |

Sample size |

Prevalence (%) |

|

Factors associated with treatment, awareness and control |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Female | Total | Aware (% of hypertensive) | Treated (% of aware) | Control (% treated) | |||||

|

Comoros |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Solet JL , 2008 [14] |

Islands |

30–69 |

|

|

1268 |

44.0 |

33.0 |

|

27.0 |

Elderly more aware than the young |

|

Eritrea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mufunda, 2006 [15] |

Rural and Urban |

15–64 |

1160 |

1182 |

2342 |

15.6 |

20.0 |

|

|

|

|

Ethiopia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Muluneh AT, 2012 [16] |

Rural and urban |

15–64 |

2084 |

2385 |

4469 |

9.3 |

|

|

27.0 |

|

| Awoke A , 2012 [17] |

Urban |

>35 |

|

|

679 |

28.3 |

63.0 |

|

42.2 |

Obesity and low physical activity associated with poor control |

| Tesfaye F, 2009 [18] |

Urban |

25–64 |

1398 |

1875 |

3713 |

31.5 |

35.2 |

11 |

28.0 |

|

|

Kenya |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| van de Vijver SJ, 2013 [19] |

Urban slums |

>18 |

2794 |

2396 |

5190 |

12.3 |

19.5 |

47 |

21.0 |

|

| Jenson A, 2011 [20] |

Coastal area |

|

162 |

307 |

469 |

43.1 |

46.5 |

31.2 |

7.3 |

Women more aware OR 4.58 (1.81–11.64); better treated OR 4.02(1.89–8.54) and controlled OR 8.1(1.81–11.64) Older >60 more aware OR6.01(1.11–32.48), better treated OR3.22(1.00–10.32) and controlled 3.22(1.04–9.99) |

| Hendriks EM, 2011 [21] |

Rural |

>18 |

847 |

1264 |

2111 |

21.4 |

17.0 |

9 |

8.0 |

|

|

Mozambique |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Damasceno et al., 2009 [22] |

Rural and urban |

25–64 |

1281 |

1800 |

3081 |

33.1 |

14.8 |

48.1 |

39.9 |

Women more aware (p < 0.007), better treated (P < 0.021) and better controlled (p < 0.001) |

| Seychelles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bovet et al., 2004 [23] |

Nationalwide survey |

|

1255 |

568 |

1823 |

39.2 |

65.0 |

62 |

24.1 |

Women more aware, treated and controlled |

|

Tanzania |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dewhurst et al., 2012 [25] |

Elderly |

>70 |

972 |

1251 |

2223 |

70.0 |

37.7 |

6.1 |

0.9 |

Men better treated, women more controlled |

| Hendriks EM, 2011 [21] |

Urban |

>18 |

423 |

623 |

1046 |

23.7 |

18.0 |

9 |

5.0 |

|

| Bovet P.,2002 [24] |

|

|

9254 |

3659 |

5645 |

29.1 |

31.0 |

11 |

6.5 |

Women, better educated well controlled |

| Edwards R et al., 2000 [26] |

Rural and urban |

>15 |

402 |

526 |

928 |

30.0 |

20.0 |

10 |

<1.0 |

No difference in rural and urban |

|

Uganda |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Musinguzi, 2013 [27] |

Rural |

>15 |

4563 |

2940 |

1623 |

27.2 |

28.2 |

51.6 |

9.4 |

Women more aware, controlled |

|

Angola |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pires JE, 2013[28] |

Mainly urban |

18-64 |

853 |

611 |

1,464 |

23.0 |

21.6 |

13.9 |

33.0 |

Awareness, higher in women (p < 0.001); older subjects (p < 0.0001); non-smokers (p < 0.009). Lower in heavy alcohol drinkers (p < 0.007) |

|

Cameroon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Kamadjeu RM et al., 2006 [29] |

Nationwide survey |

>15 |

4007 |

6004 |

10,011 |

24.1 |

23.0 |

40.0 |

|

Older age, longer duration of HTN predicted awareness and treatment |

| Dzudie A et al., 2012 [30] |

Nationwide screen |

>15 |

2120 |

1117 |

1,003 |

47.5 |

37.1 |

59.9 |

24.6 |

|

|

DRC. (Kinshasa) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Katchunga PB, 2011 [31] |

Rural and urban |

>20 |

|

|

699 |

40.2 |

42.5 |

30.5 |

13.6 |

|

|

Gabon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ngoungou EB, 2012 [32] |

|

>40 |

313 |

423 |

736 |

51.9 |

9.9 |

19.4 |

5.8 |

|

|

Zimbambwe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Matenga, 1996 [33] |

|

> 34 |

|

|

749 |

33.3 |

26.1 |

22.4 |

47.8 |

|

|

Algeria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Temmar M, 2007 [34] |

Urban > rural |

40–99 |

637 |

711 |

1348 |

44.0 |

|

30.0 |

25.0 |

Women controlled better than men (p < 0.001) |

| Nejjari C et al., 2013 [35] |

Multinational |

>18 |

27296 |

17339 |

10292 |

45.4 |

7.0 |

91.2 |

37.5 |

Control better in urban areas (p < 0.00001), younger (p < 0.01), female(p < 0.01); university level (p < 0.00001); non-smokers (p < 0.0001); those with normal BMI (p < 0.00001); normal cholesterol level (p < 0.01) |

|

Egypt |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ibrahim MM, 1995 [36] |

Nationwide survey |

25–95 |

2928 |

3804 |

6733 |

36.3 |

37.5 |

23.9 |

8.0 |

Better awareness, treatment and control in urban vs. rural. Better awareness and treatment in those with severe HTN. Better awareness and control in women and elderly |

|

Tunisia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Romdhane BH, 2012 [37] |

Nationwide survey |

35–70 |

|

|

8007 |

30.6 |

38.8 |

84.4 |

24.1 |

Awareness better in older age group, females, lower education, urban subjects |

| Hammami, 2011 [38] |

Urban elderly |

>65 |

202 |

396 |

598 |

52.0 |

81.0 |

78.0 |

30.7 |

Awareness better in elderly population, those with free medications & the insured |

| Romdhane BH, 2005 [38] |

|

40–60 |

|

|

1837 |

44.0 |

41.0 |

74.0 |

18.0 |

|

|

South Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Maepe LM, 2012 [50] |

Gold miners |

18–69 |

3867 |

430 |

4297 |

39.5 |

|

42.0 |

31.0 |

|

| Malhotra R, 2008 [51] |

|

|

107 |

530 |

637 |

40.0 |

49.2 |

|

|

Younger age associated with better awareness; 35–54 yrs [OR 0.33 (0.19–0.57)] and 55 yrs [OR 0.27 (0.14–0.54)] c.f age 18–34 |

| Steyn K, 2008 [52] |

Nationwide |

|

5738 |

8064 |

13801 |

21.0 |

M-41 F-67 |

M-39 f-58 |

M-26 F 38 |

Better control predicted by SES: richest vs poorest OR 2.33(1.17–4.62) ; Race asian vs black OR 1.76(1.03–3.02); Age: oldest age group vs youngest OR 26.23 (4.92–141); Insurance: non-insured vs insured OR 0.59 (0.38–0.91) |

|

Namibia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hendriks EM, 2011 [21] |

Urban |

>18 |

771 |

962 |

1733 |

38.0 |

38.0 |

17 |

12 |

|

|

Benin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Houinato DS, 2012 [40] |

|

|

3461 |

3392 |

6853 |

27.9 |

22.5 |

4.8 |

1.9 |

|

|

Ghana |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agyemang, 2006 [41] |

Rural urban |

>16 |

787 |

644 |

1431 |

29.4 |

34.0 |

28 |

6.2 |

Awareness better in older age (≥50-yr olds cf 16-34-yr olds [OR = 6.14, (2.98–12.64). Treatment better in older age ≥50-year-olds OR: 6.25 ( 2.87–13.62); overweight OR 1.85(1.02, 3.34); traders OR 2.51(1.03–7.40]) Control better in traders OR 2.51 (1.03–7.40) but poor in old age: ≥50-year-olds OR 0.11( 0.01–0.60) |

| Addo, 2006 [42] |

Rural |

>18 |

107 |

255 |

362 |

22.4 |

33.2 |

16.7 |

|

|

| Amoah, 2003 [63] |

Urban |

>25 |

1893 |

2840 |

4733 |

28.3 |

34.0 |

18 |

4.0 |

|

|

Nigeria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ulasi II, 2011 [44] |

Market community |

|

379 |

352 |

731 |

54.2 |

49.8 |

|

|

|

| Oladapo OO, 2010 [45] |

|

|

873 |

1127 |

2000 |

39.2 |

14.2 |

18.6 |

|

Transport, lack of drugs at health units, competing priorities |

| Hendriks EM, 2011 [21] |

Rural, multinational |

>18 |

1247 |

1431 |

2678 |

19.3 |

8.0 |

5.0 |

3.0 |

|

| Omuemu, 2007 [46] |

Rural |

|

|

|

590 |

20.2 |

18.5 |

77.3 |

29.2 |

Women more aware, educated, elderly |

| Ekwunife, 2010 [47] |

|

>18 |

364 |

392 |

756 |

21.1 |

30.0 |

21.0 |

9.0 |

Men more aware, women more controlled |

|

Senegal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Macia E, 2012 [48] |

Urban |

>50 |

263 |

237 |

500 |

64.5 |

49.5 |

70.6 |

17.4 |

Better awareness for women OR 2.4(1.41–4.07); elderly > 70 yrs OR 2.15(1.11–4.17) but worse for the educated > 8 years OR 2.15 (1.01–4.6 ); those who had not visited HCW within the year OR 0.37 ( 0.23–0.6) Better treatment and control for those who had visited HCW within the last year (P < 0.001) |

|

Togo |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Yayehd K, 2011 [49] | 2002 | 1095 | 905 | 36.7 | 42.4 | |||||

HTN hypertension, HCW Health care workers, SES socioeconomic status, BMI body mass Index, OR (95% CI)- Odds ratio followed by 95% CI.

The total number of participants in the review was 121, 220. The sample size ranged from 375 subjects in a market place in Nigeria [44] to 27296 in a multinational study in North Africa [35]. The age of the participants ranged from 15 years to 99 years. Five studies focused on the middle aged and elderly populations above forty years [25,32,34,38,39]. All the studies had both genders (male and female) represented. In most of the studies, the women participants were more than the men. In studies that targeted special communities- gold miners, slum dwellers and market communities- the men had more representation.

Prevalence of hypertension

There was a wide variation in prevalence of hypertension. Most of the prevalence rates were not age-standardised which made comparisons difficult. Among the studies that considered younger populations under 35 years, the prevalence ranged from 9.3% in an Ethiopian population to 48.1% in a Mozambican population [16,22]. As expected, those studies that involved the elderly populations had higher prevalence of hypertension reaching 70% in an urban Tanzanian population aged more than 70 years [25].

Awareness

Awareness in this review was described as prior knowledge of hypertensive status. The lowest levels of awareness were found in rural communities in Nigeria (8%), Uganda (10%) and Gabon (9%)[21,27,32]. The lowest prevalence of awareness in urban areas was 12.3% among slum dwellers in Nairobi. The highest awareness rates were found in the studies that considered elderly subjects reaching 81% in urban elderly populations of Tunisia [39]. Generally, studies from North African countries showed the highest levels of awareness. The large multinational Epidemiological Trial of Hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA) that included 27296 subjects revealed awareness rate of 71% among hypertensive patients [35]. West and central Africa seemed to have the lowest levels of awareness of hypertension status.

Treatment

The treatment of hypertension ranged from 5% in a rural Nigerian community to 91.2% in urban North African populations [21,35]. East African populations had the lowest levels of treatment while North African countries had the highest levels. In studies done in Tanzania, for example, the treatment rates ranged between 6.1% and 11% whereas those done in North Africa varied between 24% in an Egyptian national wide survey and 91.2% in the ETHNA study [24,25,35,36]. There was no clear difference in treatment rates between urban and rural populations across the regions.

Control rates

Despite varying rates of awareness and treatment, the control rates were uniformly low and never exceeded 45%. Tanzanian populations- both urban and rural- had the lowest levels ranging from as low as <1% and never exceeding 6.5% in all the four studies that spanned twelve years. As with awareness and treatment rates, the North African studies showed the highest rate of control. The least levels of control in North Africa were recorded in Egypt at 8% with the highest recorded in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria in the multinational ETHNA study [35,36].

Factors affecting treatment awareness and control

Only 24 out of the 44 studies attempted to review any factors associated with awareness, treatment and control status. In all the studies, the older age group had better awareness and treatment rates. However, this did not universally translate into better control of the blood pressure. In fact, two studies reported better control in the young hypertensive patients [35,41]. Additionally, most studies revealed better prevalence of awareness, treatment and control among the women. Even the two studies that showed better awareness of hypertensive status in men eventually revealed superior treatment and control status in the women [25,47].

All the studies that had a comparison of rural and urban dwellings showed generally better hypertension treatment and control status in the urban areas. Additionally, subjects with better formal education and literacy levels seemed to have better control. While socio-economic status was not a frequently recorded variable in the studies, the patients who had health insurance or who had access to private care had better control [52]. Moreover North African countries, most of which have access to universal health insurance had better detection and treatment profiles, although these did not translate into better control rate [39].

Discussion

There has been a wealth of information on the prevalence of hypertension on the African continent. A 2007 systematic review by Addo et al. had illustrated the high prevalence of hypertension in numerous African states [12]. Although our search terms did not include prevalence, this systematic review reveals varied levels of prevalence across countries, a great many of which confirm persisting high rate. In a high prevalence setting like Africa, it is of utmost importance to describe not only the detection rate but also awareness, treatment and control as well as the factors that influence these rates. This would enable the formulation of relevant tailor-made control strategies in order to reduce the complications of uncontrolled hypertension. This systematic review is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive analysis on awareness, treatment and control on the African continent to date.

Our results show generally low levels of awareness of hypertensive status with North African countries having relatively better levels. The levels in Africa are much lower than those in North America and Europe where temporal reviews have shown an improvement in awareness from twenty years ago when the levels where similar to the level currently seen in Africa to the present rate of over 65% [53]. Most of this improved awareness has been attributed to rigorous education programs on hypertension after the realization that hypertension was a major player in morbidity and mortality in these countries. Whereas the heterogeneous nature of the designs of the study reviewed here could not allow the establishment of a temporal trend in this review, no improvement was realised in countries that had multiple consecutive studies such as Tanzania. It is possible that similar appreciation of hypertension as leading cause of death would lead to improved education and therefore improved awareness.

The treatment rates found by our review in North Africa were much higher than those found elsewhere on the continent. It is possible that the availability of health insurance in countries such as Tunisia which covers both diagnosis and treatment steers these high levels of treatment. In Massachusetts USA, universal health insurance coverage has led to improved diagnosis and control of hypertension leading to a reduction in hypertension related hospitalisations and deaths [54]. It is possible that hypertension status will improve in countries aiming to attain universal health coverage such as South Africa. In other parts of Africa, nationalized health insurance remains out of reach. Most Africans pay out-of-pocket for their health expenses, which are supplemented somewhat by a few free services from government and donor organizations which mainly focus on infectious disease treatment with HIV/AIDS control efforts taking a lion’s share of this funding [55]. This calls for more innovative ways of financing care for chronic non-communicable disease on the continent.

The studies considered in this review revealed generally dismal rates of control of hypertension. The lowest rates of control were seen in Tanzania in studies spanning 10 years. Even in countries that had impressive rates of treatment, control of blood pressure to target remained elusive in many. This means that treatment of hypertension does not guarantee control, the ultimate predictor of outcomes. Several of the included studies from different countries blamed various factors for poor blood pressure control. These can generally be categorised as such as the health-system deficiencies, patients’ non-adherence and the physicians’ inertia in treating hypertension and they seem to be in play on the African continent. For example, the lack of anti-hypertensive medication at health facilities and the long distance to the health facilities reported in some studies are characteristic health system shortcomings hindering the achievement of control [28,44]. On the other hand the lack of time and reported competing priorities are classical patient and physician factors adding to the problem [45].

Blood pressure in women was generally better controlled than in men in Africa. In two studies in Tanzania and Nigeria, the men were more aware of their status and were more likely to receive treatment. Still, the women achieved better control rates. The issue of gender differences in hypertension has been a subject of intense research. It is now recognised that young men are more likely to develop hypertension than women, a dynamic that has been blamed on androgen mediated abnormalities in pressure natrieusis [56]. However, large meta-analyses of hypertension treatment trials have failed to document gender differences in response to antihypertensive medication meaning that the poor control of hypertension documented in men is probably due to socio-economic and cultural factors [57]. In other parts of the world, control of blood pressure seems to be poorer in women. This is possibly because these studies have largely considered elderly men and women [58,59]. In our review women of all age groups seemed to have better control. In various studies in the African setting, the women seem to have better health seeking behaviour for chronic disease than men [60,61]. It is also possible that women benefit from screening due to more contact with healthcare facilities during the reproductive years [62]. The men, on the other hand, are less enthusiastic in seeking care. Indeed in one included study from Angola, men reportedly did not pick up their antihypertensive medication because they lacked time [28]. The finding supports the establishment of gender-specific programs for the treatment and control of blood pressure.

There were certain limitations in this review. The use of one database may have limited the number of articles obtained for the review. However, by searching the PubMed database we limited our search to peer-reviewed sources which offered a firm guarantee that the publications used were appropriate for review [63].

As previously mentioned, these studies were heterogeneous in nature which made further analysis difficult. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the considered studies complicated efforts to discuss the trends in awareness, treatment and control. In Tanzania, frequent studies have been done in the capital Dar es Salaam over time and so we commented on trends [24,26]. There is need to carry out surveillance or follow-up cohorts in order to study the trends of hypertension status. A further limitation with most of the reviewed studies was the failure to study the factors that contributed to the current hypertension status on the continent which calls for systematic study of these factors to inform interventions and policy. Other draw-backs included non-random selection of participants in some of the studies [30,44] the under-representation of the central African region.

Conclusion

This systematic review confirms the low levels of treatment and awareness. Most notably, the level of control is abysmal in most countries in Africa, which implies that diagnosis and treatment does not guarantee reaching targets of control. This situation explains the poor outcomes of patients affected with hypertension on the continent. While health system factors play a key part in perpetuating this state of affairs, patient factors are also important determinants of control. These factors may differ in gender and on different parts of the continent necessitating tailored research and policy formulation to improve the outcomes of patients affected by hypertension. In addition, there is need to design tailored chronic care models on a continent whose focus has thus far been the control of acute infectious disease.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

JK designed the review, conducted the literature search and drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript and contributed to its content.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

James Kayima, Email: jkkayima@gmail.com.

Rhoda K Wanyenze, Email: rwanyenze@musph.ac.ug.

Achilles Katamba, Email: akatamba@yahoo.com.

Elli Leontsini, Email: eleontsi@jhsph.edu.

Fred Nuwaha, Email: nuwahaf@yahoo.co.uk.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Alison Kinengyere, the librarian at the Makerere University College of Health Sciences School of Medicine, Evelyn Bakengesa of the Publication and Information Centre, Makerere University College of Health Sciences and Rhoda Namubiru, Administrator of the MEPI- Linked Cardiovascular program for assisting in the literature search and submission of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant R24TW008861 (MEPI- Linked: Building Capacity for cardiovascular research and Training in Uganda.) funded by Office of the United States Global Aids Coordinator, National Institutes of Health and Health Resources and Services Administration. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting offices.

References

- Gaziano TA. Cardiovascular disease in the developing world and its cost-effective management. Circulation. 2005;112(23):3547–3553. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.591792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747–1757. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwan A. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N. Commentary. Non-communicable disease and priorities for health policy in sub-Saharan Africa. Health policy and planning. 2001;16(4):351. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.4.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand E. Cardiovascular Disease in Developing Countries. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland GH. The World Health Report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Weinstein MC. The global cost of nonoptimal blood pressure. Journal of hypertension. 2009;27(7):1472. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832a9ba3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q, Dillon CF, Burt VL, Gillum RF. Association of hypertension treatment and control with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality among US adults with hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23(1):38–45. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He FJ, MacGregor GA. Cost of poor blood pressure control in the UK: 62,000 unnecessary deaths per year. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17(7):455–457. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, MacMahon S. Blood pressure, antihypertensive drug treatment and the risks of stroke and of coronary heart disease. Br Med Bull. 1994;50(2):272–298. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials: blood pressure lowering treatment trialists’ collaboration. Lancet. 2000;356(9246):1955–1964. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addo J, Smeeth L, Leon DA. Hypertension in Sub-Saharan Africa. Hypertension. 2007;50(6):1012–1018. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.093336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solet JL, Baroux N, Pochet M, Benoit-Cattin T, De Montera AM, Sissoko D. et al. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors in Mayotte in 2008: the MAYDIA study. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37(3):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufunda J, Mebrahtu G, Usman A, Nyarango P, Kosia A, Ghebrat Y. et al. The prevalence of hypertension and its relationship with obesity: results from a national blood pressure survey in Eritrea. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(1):59–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muluneh AT, Haileamlak A, Tessema F, Alemseged F, Woldemichael K, Asefa M. et al. Population based survey of chronic non-communicable diseases at gilgel gibe field research center, southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2012;22(S):7–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awoke A, Awoke T, Alemu S, Megabiaw B. Prevalence and associated factors of hypertension among adults in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12(113):1471–2261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-12-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesfaye F, Byass P, Wall S. Population based prevalence of high blood pressure among adults in Addis Ababa: uncovering a silent epidemic. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9(39):1471–2261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Vijver SJ, Oti SO, Agyemang C, Gomez GB, Kyobutungi C. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among slum dwellers in Nairobi, Kenya. J Hypertens. 2013;19:19. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835e3a56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenson A, Omar AL, Omar MA, Rishad AS, Khoshnood K. Assessment of hypertension control in a district of Mombasa Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(3):293–306. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2010.510478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks ME, Wit FW, Roos MT, Brewster LM, Akande TM, de Beer IH. et al. Hypertension in Sub-Saharan Africa: cross-sectional surveys in four rural and urban communities. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasceno A, Azevedo A, Silva-Matos C, Prista A, Diogo D, Lunet N. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in mozambique: urban/rural gap during epidemiological transition. Hypertension. 2009;54(1):77–83. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.132423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovet P. The epidemiologic transition to chronic diseases in developing countries: cardiovascular mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in Seychelles (Indian Ocean): investigators of the Seychelles heart study. Soz Praventivmed. 1995;40(1):35–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01615660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovet P, Ross AG, Gervasoni JP, Mkamba M, Mtasiwa DM, Lengeler C. et al. Distribution of blood pressure, body mass index and smoking habits in the urban population of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and associations with socioeconomic status. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(1):240–247. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhurst MJ, Dewhurst F, Gray WK, Chaote P, Orega GP, Walker RW. The high prevalence of hypertension in rural-dwelling Tanzanian older adults and the disparity between detection, treatment and control: a rule of sixths? J Hum Hypertens. 2012;13(10):59. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R, Unwin N, Mugusi F, Whiting D, Rashid S, Kissima J. et al. Hypertension prevalence and care in an urban and rural area of Tanzania. J Hypertens. 2000;18(2):145–152. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musinguzi G, Nuwaha F. Prevalence awareness and control of hypertension in Uganda. PloS one. 2013;4:e62236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires JE, Sebastiao YV, Langa AJ, Nery SV. Hypertension in Northern Angola: prevalence, associated factors, awareness, treatment and control. BMC Publ Health. 2013;13(1):90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamadjeu RM, Edwards R, Atanga JS, Unwin N, Kiawi EC, Mbanya JC. Prevalence, awareness and management of hypertension in Cameroon: findings of the 2003 Cameroon burden of diabetes baseline survey. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(1):91–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzudie A, Kengne AP, Muna WF, Ba H, Menanga A, Kouam Kouam C. et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a self-selected Sub-Saharan African urban population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):2012–001217. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katchunga PB, M’Buyamba-Kayamba JR, Masumbuko BE, Lemogoum D, Kashongwe ZM, Degaute JP. et al. Hypertension in the adult Congolese population of Southern Kivu: results of the vitaraa study. Presse Med. 2011;40(6):3. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngoungou EB, Aboyans V, Kouna P, Makandja R, Ecke Nzengue JE, Allogho CN. et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in Gabon: a population study. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;105(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matenga JA, Allain TJ, Wilson AO, Adamchak DJ, Senzanje B, Mushangi E. et al. Hypertension management in Zimbabwe–awareness, treatment and blood pressure control: a community-based study. S Afr Med J. 1997;87(10):1371–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmar M, Labat C, Benkhedda S, Charifi M, Thomas F, Bouafia MT. et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in the Algerian Sahara. J Hypertens. 2007;25(11):2218–2226. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282dc7549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejjari C, Arharbi M, Chentir MT, Boujnah R, Kemmou O, Megdiche H. et al. Epidemiological trial of hypertension in North Africa (ETHNA): an international multicentre study in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. J Hypertens. 2013;31(1):49–62. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835a6611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MM, Rizk H, Appel LJ, el Aroussy W, Helmy S, Sharaf Y. et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in Egypt. results from the Egyptian national hypertension project (NHP). NHP investigative team. Hypertension. 1995;26(6 Pt 1):886–890. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Romdhane H, Ben Ali S, Skhiri H, Traissac P, Bougatef S, Maire B. et al. Hypertension among Tunisian adults: results of the TAHINA project. Hypertens Res. 2012;35(3):341–347. doi: 10.1038/hr.2011.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Romdhane H, Skhiri H, Bougatef S, Ennigrou S, Gharbi D, Chahed MK. et al. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control: results from a community based survey. Tunis Med. 2005;5:41–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammami S, Mehri S, Hajem S, Koubaa N, Frih MA, Kammoun S. et al. Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among the elderly living in their home in Tunisia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011;11(65):1471–2261. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houinato DS, Gbary AR, Houehanou YC, Djrolo F, Amoussou M, Segnon-Agueh J. et al. Prevalence of hypertension and associated risk factors in Benin. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2012;60(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang C, Bruijnzeels MA, Owusu-Dabo E. Factors associated with hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in Ghana, West Africa. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(1):67–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addo J, Amoah AG, Koram KA. The changing patterns of hypertension in Ghana: a study of four rural communities in the Ga District. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):894–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoah AG. Hypertension in Ghana: a cross-sectional community prevalence study in greater Accra. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(3):310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulasi II, Ijoma CK, Onwubere BJ, Arodiwe E, Onodugo O, Okafor C. High prevalence and low awareness of hypertension in a market population in enugu, Nigeria. Int J Hypertens. 2011;27(869675):869675. doi: 10.4061/2011/869675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oladapo OO, Salako L, Sodiq O, Shoyinka K, Adedapo K, Falase AO. A prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a rural Yoruba south-western Nigerian population: a population-based survey. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21(1):26–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omuemu VO, Okojie OH, Omuemu CE. Awareness of high blood pressure status, treatment and control in a rural community in Edo State. Niger J Clin Pract. 2007;10(3):208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekwunife OI, Udeogaranya PO, Nwatu IL. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in a nigerian population. Health. 2010;2(7):731–735. doi: 10.4236/health.2010.27111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Duboz P, Gueye L. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among adults 50 years and older in Dakar, Senegal. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2012;23(5):265–269. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2011-039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayehd K, Damorou F, Akakpo R, Tcherou T, N’Da NW, Pessinaba S. et al. Prevalence and determinants of hypertension in Lome (Togo): results of a screening in May 2011. Ann Cardiol Angeiol. 2013;62(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maepe LM, Outhoff K. Hypertension in goldminers. S Afr Med J. 2011;102(1):30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra R, Puoane T, Hoyo C, Hughes G, Ostbye T. Prevalence and awareness of hypertension in an urban township of South Africa: compelling need for action. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):401–402. Autumn;18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steyn K, Bradshaw D, Norman R, Laubscher R. Determinants and treatment of hypertension in South Africans: the first demographic and health survey. S Afr Med J. 2008;98(5):376–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlister FA, Wilkins K, Joffres M, Leenen FH, Fodor G, Gee M. et al. Changes in the rates of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Canada over the past two decades. Cmaj. 2011;183(9):1007–1013. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joynt KE, Chan D, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Insurance expansion in massachusetts did not reduce access among previously insured medicare patients. Health Aff. 2013;32(3):571–578. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atim C, Fleisher LK, Hatt L, Musau S, Arur A. Health Financing in Africa Today: Challenges and Opportunities. Washington, DC: Africa’s Health, Academy for Educational Developmen, and Bethesda, MD: Health Systems 20/20 Project; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reckelhoff JF. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2001;37(5):1199–1208. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.37.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull F, Woodward M, Neal B, Barzi F, Ninomiya T, Chalmers J. et al. Do men and women respond differently to blood pressure-lowering treatment? results of prospectively designed overviews of randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(21):2669–2680. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins K, Gee M, Campbell N. The difference in hypertension control between older men and women. Health Rep. 2012;23(4):33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyhani S, Scobie JV, Hebert PL, McLaughlin MA. Gender disparities in blood pressure control and cardiovascular care in a national sample of ambulatory care visits. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):1149–1155. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.107342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufunda E, Albin B, Hjelm K. Differences in health and illness beliefs in Zimbabwean men and women with diabetes. Open Nurs J. 2012;6:117–125. doi: 10.2174/1874434601206010117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm K, Nambozi G. Beliefs about health and illness: a comparison between Ugandan men and women living with diabetes mellitus. Int Nurs Rev. 2008;55(4):434–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2008.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M, Lunet N, Azevedo A, Barros H. Differences in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension between developing and developed countries. Journal of hypertension. 2009;27(5):963–975. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283282f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, web of science, and Google scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22:338–342. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]